Abstract

Glycogen storage disease type Ia (GSD-Ia) patients develop renal disease of unknown etiology despite intensive dietary therapies. Interestingly, renal disease in GSD-Ia shares many clinical and pathological similarities to diabetic nephropathy, providing a model to study GSD-Ia nephropathy. In this study we examined whether the angiotensin system mediates renal fibrosis in GSD-Ia mice. The expression of angiotensinogen, angiotensin type 1 receptor, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) were elevated in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice compared to the controls. While increased renal expression of angiotensinogen was evident in 2-week-old GSD-Ia mice, renal expression of TGF-β1 and CTGF did not increase until age 3 weeks, consistent with the up-regulation of TGF-β and CTGF by angiotensin II. The expression of genes for extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, fibronectin, and collagens I, III, and IV were also elevated in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice, compared to controls. Renal fibrosis was characterized by a marked increase in the synthesis and deposition of ECM proteins in the renal cortex and histological abnormalities which included tubular basement membrane thickening, tubular atrophy, tubular dilation, and multifocal interstitial fibrosis. Our results suggest that activation of the angiotensin system plays an important role in the pathophysiology of renal disease in GSD-Ia.

Keywords: angiotensin, connective tissue growth factor, glycogen storage disease type Ia, renal fibrosis, transforming growth factor-β1

INTRODUCTION

Glycogen storage disease type Ia (GSD-Ia, MIM232200) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a deficiency in glucose-6-phosphatase-α (G6Pase-α, also known as G6PC), a key enzyme in glucose homeostasis that catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) to glucose and phosphate in the terminal step of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis.1 GSD-Ia patients manifest a phenotype of disturbed glucose homeostasis characterized by fasting hypoglycemia, hepatomegaly, nephromegaly, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperuricemia, lactic acidemia, and growth retardation.1 Although renal involvement in GSD-Ia was noted in von Gierke’s pathological description2, and kidney enlargement is commonly seen in GSD-Ia, chronic renal disease was not widely recognized as a major complication until the late 1980’s when it was reported by Chen and coworkers.3 Their renal biopsies of GSD-Ia patients revealed interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with marked glomerular basement-membrane thickening, which was subsequently confirmed in additional GSD-Ia patients.4,5 Renal disease as a long-term complication in GSD-Ia is now well established. Over the last two and a half decades, effective dietary therapies, including nocturnal nasogastric infusion of glucose6 and/or oral administration of uncooked cornstarch7 have significantly alleviated the metabolic abnormalities and delayed the clinical manifestation of chronic renal disease and renal insufficiency in GSD-Ia patients. However, glomerular hyperfiltration, hypercalciuria, hypocitraturia that worsens with age, and urinary albumin excretion still occur in metabolically compensated GSD-Ia patients.8,9 While the molecular basis of the GSD-Ia disorder is now known, the molecular mechanism(s) responsible for the development of renal disease in GSD-Ia is still poorly understood.

Renal disease in GSD-Ia5,10 exhibits a similar clinical course and pathology to diabetic nephropathy.11,12 Both dysfunctions start with a long period of silent disease during which glomerular hyperfiltration is the only demonstrable renal abnormality. This is followed by the development of microalbuminuria, proteinuria, and ultimately, renal failure. Pathologically, both exhibit interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and glomerulosclerosis with marked glomerular basement-membrane thickening. Tissue fibrosis observed in many kidney diseases including diabetic nephropathy is the result of excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins13,14, including fibronectin and collagens type I, III, and IV. The ECM proteins accumulate during the evolution of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis, contributing to the impairment of renal function and the eventual organ failure.13-15 Studies have shown that the angiotensin (Ang) system plays a pivotal role in many of the associated pathophysiologic changes in renal fibrosis.15-19

In the Ang system, angiotensinogen (Agt) is the precursor of the multifunctional cytokine, Ang II, which is produced from two sequential enzymatic reactions - the conversion of Agt to Ang I by renin and the conversion of Ang I to Ang II by the Ang converting enzyme.20 Ang II stimulates the proliferation of mesangial cells, glomerular endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, and acts as a profibrogenic factor.15-19 Many profibrotic effects of Ang II are mediated by the multifunctional growth factor, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)15, whose expression is also augmented by Ang II.21 TGF-β1 acts to increase the expression of the ECM genes and also inhibits the production of ECM degradative proteins15,22,23, leading to the ECM protein deposition that typifies progressive renal disease. In addition, TGF-β1 is a potent inducer of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition that characterizes the phenotype of renal interstitial fibrosis.15 The TGF-β1 induced renal disease is characterized by accumulation of matrix protein, interstitial fibrosis, mesangial expansion, and glumerulosclerosis.15,22-24 Ang II also induces the expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)25, a prosclerotic cytokine and a TGF-β1-inducible immediate early gene that acts downstream of TGF-β1.26,27 CTGF mediates TGF-β1-stimulated matrix protein expression and plays a key role in progressive renal fibrosis.

All components of the Ang system are found in the renal proximal tubular cells20 where G6Pase-α is primarily expressed.28 GSD-Ia patients suffer from hyperuricemia despite intensive dietary therapies.1 Studies of an experimentally induced mild hyperuricemia in rats have suggested that an elevation in circulating serum uric acid is strongly associated with the development of renal disease.29,30 These studies also showed that a uric acid-induced activation of the intrarenal Ang system plays a key role in hyperuricemia-mediated renal damage.29,30 The kidneys of GSD-Ia patients also have increased levels of G6P, the intracellular form of glucose, resulting from enhanced glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, compounded by the inability of these patients to hydrolyze G6P to glucose.1 High glucose stimulated mRNA expression and protein synthesis of Agt in proximal tubular epithelial cells.31 We hypothesized that the Ang system may be implicated in GSD-Ia nephropathy.

In previous studies of the biology and pathophysiology of GSD-Ia, we generated a G6Pase-α-deficient mouse strain that faithfully mimics the human disorder with the metabolic abnormalities characteristic of a disturbed glucose homeostasis with the exception of lactic acidemia.32 In this study, we show that the renal Ang system-mediated profibrotic pathway is up-regulated in GSD-Ia mice, providing one mechanism that can lead to the development of renal disease.

RESULTS

Increased renal expression of Agt, Ang peptides, and AT1 in GSD-Ia mice

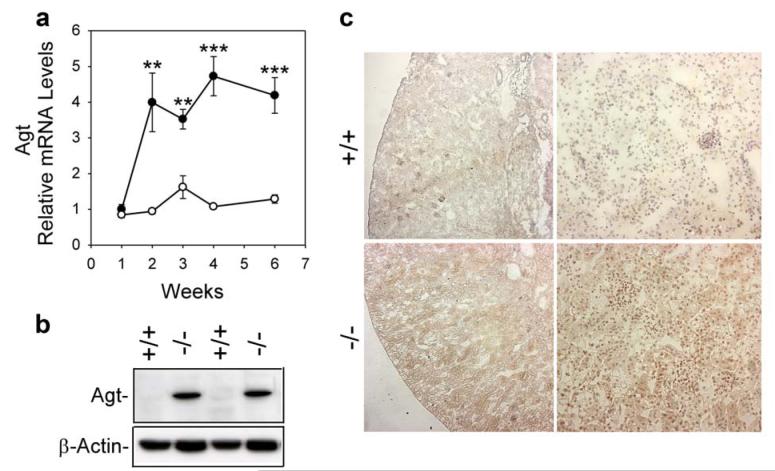

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that renal Agt mRNA levels were similar between 1-week-old GSD-Ia and their wild-type littermates (Figure 1a). While renal Agt transcripts increased only slightly in wild-type mice during postnatal development, postnatal renal Agt mRNA increased markedly in the GSD-Ia mice (Figure 1a). Consequently, renal Agt mRNA in 2-, 3-, 4-, and 6-week-old GSD-Ia mice showed on average a 4-fold higher level, compared to the age-matched wild-type mice. Western-blot analysis confirmed that the increased RNA expression correlated with an increased expression of Agt proteins in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice (Figure 1b). Immunohistochemical analysis using a polycloncal antibody against Ang I/II (N-10) that detects Agt, Ang I, and Ang II showed that within the kidneys of wild-type mice, low levels of these peptides were expressed in cortical tubular epithelial cells (Figure 1c). In contrast, GSD-Ia kidneys expressed significantly high levels of Agt, Ang I, and Ang II and in numerous proximal tubular epithelial cells (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Analysis of renal expression of the Ang system in GSD-Ia mice.

(a) Quantification of Agt mRNA in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development using real-time RT-PCR. Results are the mean ± SEM. Each point represents the average of 5 or more animals. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (b) Western-blot analysis of Agt in the kidneys of 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice. (c) Immunohistochemical analysis of Agt, Ang I, and Ang II in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice. Plates shown are kidneys from 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice at magnifications of x50 (left panels) and x200 (right panels). Representative experiments are shown.

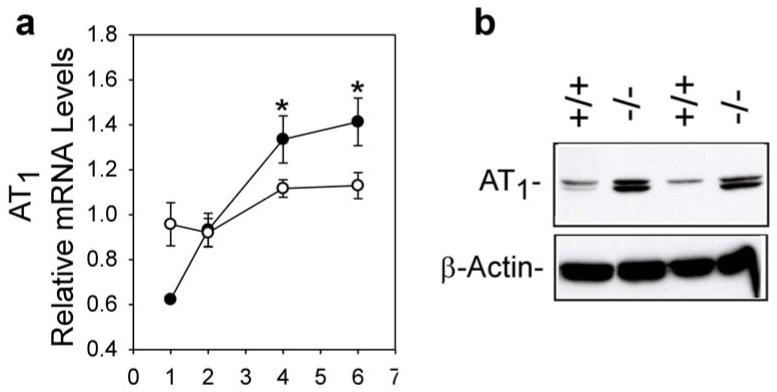

Ang II acts through two specific receptors33,34, Ang type 1 (AT1) and Ang type 2 (AT2). Real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that renal AT1 mRNA levels in 1-week-old GSD-Ia mice were only 65% of wild-type expression (Figure 2a). However, while AT1 mRNA in wild-type mice increased slowly during postnatal development, the levels increased rapidly in GSD-Ia mice. As a consequence, the renal AT1 mRNA in 4-, and 6-week-old GSD-Ia mice averaged 1.2- and 1.3-fold higher, respectively, than the wild type mice (Figure 2a). Western-blot analysis again confirmed that this correlated with an increase in the AT1 protein expression (Figure 2b). In contrast, renal expression of AT2 was similar between GSD-Ia and wild-type mice (data not shown).

Figure 2. Analysis of renal expression of AT1 in GSD-Ia mice.

(a) Quantification of AT1 mRNA in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development using real-time RT-PCR. Results are the mean ± SEM. Each point represents the average of 5 or more animals. *p < 0.05. (b) Western-blot analysis of AT1 in the kidneys of 6- week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice.

Increased renal expression of TGF-β1 and CTGF in GSD-Ia mice

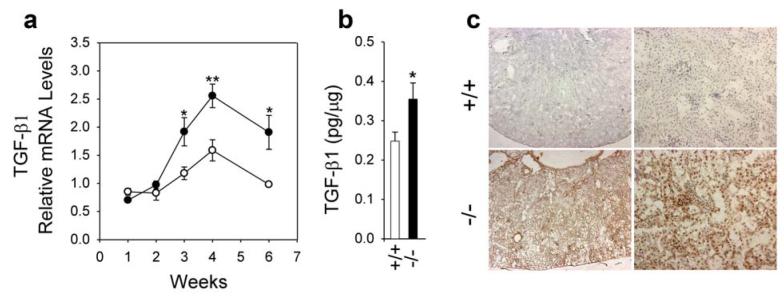

The expression of TGF-β1 can be induced by Ang II21 while the expression of CTGF can be induced by Ang II25 and TGF-β126,27, both playing key roles in Ang II-mediated renal fibrosis.15-19 Real-time RT-PCR was used to measure the level of expression of TGF-β1 and CTGF in the kidneys of GSD-Ia and wild type mice. At 2 weeks of age, the levels of TGF-β1 mRNA remained similar between the GSD-Ia and wild type mice (Figure 3a). However, in mice 3 weeks or older, renal TGF-β1 transcripts increased more rapidly in the GSD-Ia mice than their wild-type littermates (Figure 3a). As a result, renal TGF-β1 mRNA in 3-, 4-, and 6-week-old GSD-Ia mice averaged 1.6 to 1.9-fold higher compared to wild-type mice. Again, protein expression correlated with the RNA expression profiles. A quantitative immunoassay confirmed the increase in renal expression of the TGF-β1 protein in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice compared to the controls (Figure 3b). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that in wild-type kidneys, very low levels of TGF-β1 were detected in randomly scattered cortical tubular epithelial cells (Figure 3c). In GSD-Ia kidneys, moderately high levels of TGF-β1 were expressed in the glomeruli and proximal tubular epithelial cells. In addition, there were occasional low levels of TGF-β1 found in distal convoluted tubular epithelial cells and collecting tubular epithelial cells.

Figure 3. Analysis of renal expression of TGF-β1 in GSD-Ia mice.

(a) Quantification of TGF-β1 mRNA in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development using real-time RT-PCR. Results are the mean ± SEM. Each point represents the average of 5 or more animals. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (b) Quantification of TGF-β1 protein levels in the kidneys of 6-week-old wild-type (+/+; n = 14) and GSD-Ia (-/-; n = 14) mice by immunoassays. *p < 0.05. (c) Immunohistochemical analysis of TGF-β1 in the kidney of GSD-Ia mice. Plates shown are kidneys from 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice at magnifications of x50 (left panels) and x200 (right panels). Representative experiments are shown.

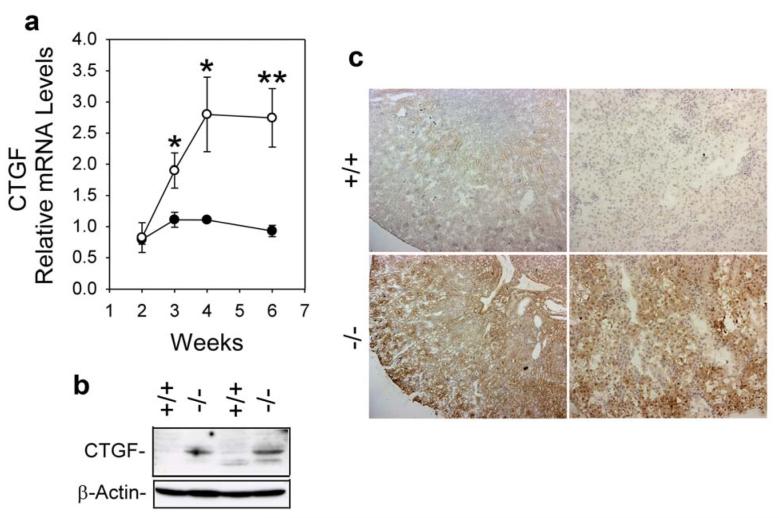

Real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that the activation profile of CTGF mRNA in GSD-Ia mice was similar to that of the TGF-β1 transcripts (Figure 4a) with CTGF mRNA in 3-, 4-, and 6-week-old GSD-Ia kidneys averaging 1.7, 2.5, and 3.0-fold higher, respectively, than the levels observed in wild-type kidneys. Western-blot analysis confirmed that the increased RNA expression correlated with an increased expression of CTGF proteins in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice (Figure 4b). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that in wild-type kidneys, very low levels of CTGF immunostaining were detected in cortical tubular epithelial cells with low levels at the corticomedullary junctions (Figure 4c). In GSD-Ia kidneys, significant high levels of CTGF protein were detected in corticomedullary tubules (Figure 4c). No increase in glomerular CTGF expression was observed.

Figure 4. Analysis of renal expression of CTGF in GSD-Ia mice.

(a) Quantification of CTGF mRNA in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development using real-time RT-PCR. Results are the mean ± SEM. Each point represents the average of 5 or more animals. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (b) Western-blot analysis of CTGF in the kidneys of 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice. (c) Immunohistochemical analysis of CTGF in the kidney of GSD-Ia mice. Plates shown are kidneys from 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice at magnifications of x50 (left panels) and x200 (right panels). Representative experiments are shown.

Increased production of renal ECM proteins in GSD-Ia mice

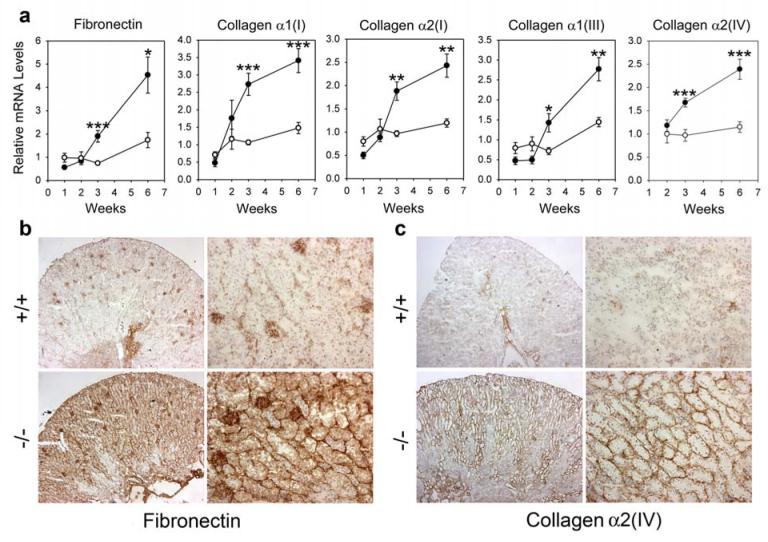

While renal fibronectin mRNA levels in GSD-Ia mice were slightly lower than those in wild-type mice during the first 2 weeks of postnatal development, renal fibronectin transcripts in GSD-Ia mice increased markedly thereafter (Figure 5a). Consequently, renal fibronectin mRNA in 3- and 6-week-old GSD-Ia mice was, on average, 2.6-fold higher than in wild-type littermates.

Figure 5. Analysis of renal expression of fibronectin and collagens in GSD-Ia mice.

(a) Quantification of mRNA for fibronectin, collagen α1(I), α2(I), α1(III), and α2(IV) in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development using real-time RT-PCR. Results are the mean ± SEM. Each point represents the average of 5 or more animals. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (b and c) Immunohistochemical analysis of fibronectin (b) and collagen α2(IV) (c) deposition in the kidney of GSD-Ia mice. Plates shown are kidneys from 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice at magnifications of x50 (left panels) and x200 (right panels). Representative experiments are shown.

During the first 2 weeks of postnatal development, renal levels of mRNA for collagen α1(I), α2(I), α1(III), and α2(IV) were similar between GSD-Ia and wild-type mice (Figure 5a). As observed with fibronectin, renal collagen α1(I), α2(I), α1(III), and α2(IV) transcripts increased more rapidly in 3- to 6-week-old GSD-Ia mice than in wild-type mice (Figure 5a), with collagen α1(I), α2(I), α1(III), and α2(IV) mRNA in the kidneys averaging a 1.7- to 2.6-fold increase compared to wild-type littermates.

To further evaluate the profibrotic phenotype of GSD-Ia kidneys, we investigated the production of the ECM proteins in 6-week-old GSD-Ia and wild-type mice using immunohistochemical analysis. Within the kidneys of wild-type mice, fibronectin was detected primarily in the glomerulus with little in the renal tubules (Figure 5b). In contrast, the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice expressed very high levels of fibronectin not only in the glomeruli but also in the renal interstitium, tubular epithelial cells, and tubular basement membranes (Figure 5b). Similarly, synthesis of collagen α1(I) (data not shown), α1(III) (data not shown) and α2(IV) (Figure 5c) were also markedly increased in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice, primarily localized at the tubular basement membranes, compared to the wild-type mice. These results confirmed the appearance and development of interstitial fibrosis in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice.

The GSD-Ia mice manifest metabolic and histological abnormalities

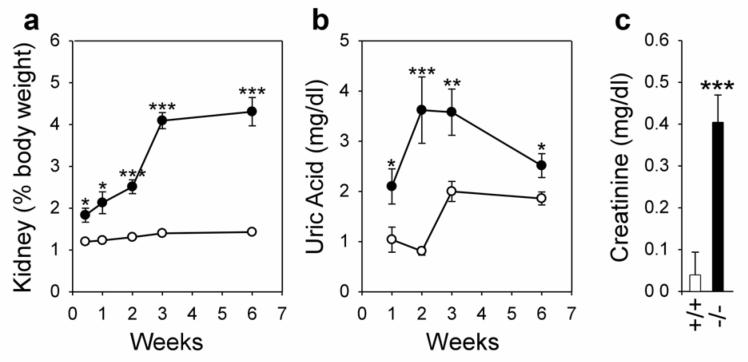

Nephromegaly is manifested clinically in GSD-Ia in both humans and mice as a result of excessive glycogen deposition.1,32 The glycogen storage in the kidneys of wild-type mice is low, with an average relative kidney weight of 1.2 to 1.4% of body weight during the 6 weeks of postnatal development (Figure 6a). On the other hand, kidney enlargement was already notable in 3 day old GSD-Ia mice (Figure 6a). The severity of kidney enlargement increased with age and the average kidney weight of 6 week-old GSD-Ia mice was elevated more than 3-fold relative to wild-type mice, to 4.3% of body weight (Figure 6a). An increase in serum levels of uric acid was also observed in 1-week-old GSD-Ia mice compared to the controls (Figure 6b) peaking at age 2 weeks before leveling off at 6 weeks at a level 1.4-fold higher than the wild-type littermates (Figure 6b). Serum creatinine, an index of altered renal function35, was also examined. The creatinine levels in the serum of 6-week-old wild-type mice were 0.04 ± 0.05 mg/dl (Figure 6c). In contrast, serum creatinine levels in 6 week-old GSD-Ia mice were increased 10-fold, reaching 0.41 ± 0.07 mg/dl (Figure 6c).

Figure 6. The GSD-Ia mice manifest nephromegaly, hyperuricemia, and an abnormal increase in serum creatinine.

(a) The weights of the kidneys relative to total body weight in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development. Each point represents the average of 5 or more animals. (b) Serum levels of uric acid in wild-type (○) and GSD-Ia (●) mice during postnatal development. Each point represents the average of 8 or more animals. (c) Serum levels of creatinine in 6-week-old wild-type (+/+; n = 19) and GSD-Ia (-/-; n = 21) mice. Values represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

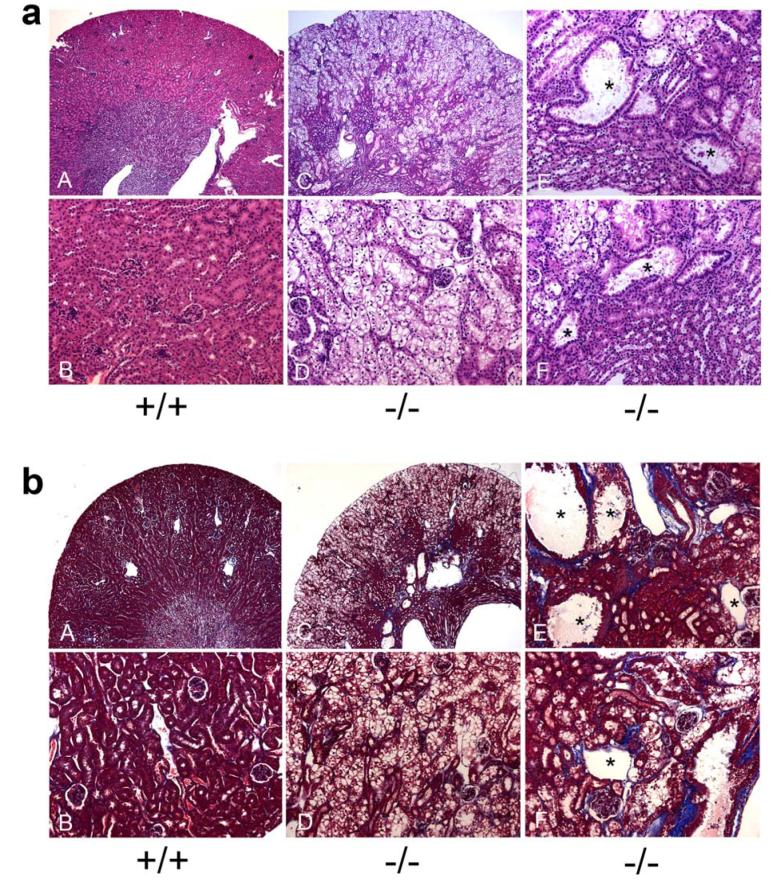

Histological examination showed that the architecture of the kidneys in 6-week-old GSD-Ia mice was altered compared to their wild type littermates. Marked glycogen accumulation in the cortex tubules resulted in enlargement of tubular epithelial cells (Figure 7a). Renal pathology also included tubular basement membrane thickening, tubular atrophy, tubular dilation, multifocal mild interstitial fibrosis, and increased Bowman’s capsule spaces (Figure 7a). Masson’s trichrome staining further demonstrated multifocal areas of mild to moderate interstitial fibrosis in GSD-Ia kidneys, primarily in the corticomedullary region (Figure 7b).

Figure 7. Histological analysis of the kidneys in GSD-Ia mice.

(a) Plates show H&E stained kidney sections in 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice at magnifications of x50 (A and C) and x200 (B, D-F). Representative experiments are shown. (b) Masson’s trichrome staining of kidney sections in 6-week-old wild-type (+/+) and GSD-Ia (-/-) mice at magnifications of x50 (A and C) and x200 (B, D-F). Interstatitial fibrosis is shown by the blue colored staining of the collagen fibers. The dilated tubules are denoted by asterisks.

DISCUSSION

GSD-Ia patients under good metabolic control for hypoglycemia still experience longer-term complications from the disease. They continue to suffer from hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, hypercalciuria, hypocitraturia, and lactic acidemia and consequently, chronic renal disease, of unknown etiology, remains a common complication of GSD-Ia.1,8,9 For those GSD-Ia patients who develop renal insufficiency, the pathology includes interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.3-5 Recently an increased expression of TGF-β1 was reported in a renal biopsy of a GSD-Ia patient manifesting proteinuria, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy36, suggesting one potential mechanism may be mediated by TGF-β1, but there was no follow-up to the observation. In this study, we examined the role of the Ang system in the development of renal disease in GSD-Ia and show that components of this system are indeed upregulated in GSD-Ia mice relative to their wild type littermates. In particular, the expression of Agt, the precursor of Ang I and Ang II20; Ang I/Ang II; and the AT1 receptor, that mediates almost exclusively the Ang II-mediated renal diseases15-19, are elevated in the kidneys of GSD-Ia mice. In addition, renal expression of the cytokines that mediate most of the profibrogenic effects of Ang II, namely TGF-β115,22,23 and CTGF26,27, are also increased in GSD-Ia mice. While the increase in renal Agt expression was evident in 2-week-old GSD-Ia mice, the increase in renal expression of TGF-β1 and CTGF was not observed until the GSD-Ia mice were at least another week older. This is consistent with the proposed mechanism because Ang II up-regulates the expression of TGF-β121 and CTGF25, and should increase first. Also as predicted by an Ang-mediated system, renal expression of genes for ECM proteins, fibronectin, collagens I, III, and IV, were all elevated in GSD-Ia mice, compared to the controls. Renal fibrosis in GSD-Ia was further demonstrated by the marked increase in the synthesis and deposition of these ECM proteins in the renal cortex. Consistent with this, histological examination in the kidneys of 6 week-old GSD-Ia mice revealed tubular basement membrane thickening, tubular atrophy, tubular dilation, increased Bowman’s capsule spaces, and multifocal mild to moderate interstitial fibrosis. Taken together, our results are consistent with Ang/TGF-β1/CTGF-mediated renal fibrosis being at least one mechanism underlying the nephropathy occurring in GSD-Ia.

The actions of cytokines and growth factors including Ang II, TGF-β1, and CTGF which are upregulated by glucose,31,37,38 also play important roles in diabetic nephropathy,11,12,39,40 suggesting a common pathway might lead to renal disease in GSD-Ia and diabetes. While diabetes is caused by a disturbance in insulin function, characterized by uncontrolled hyperglycemia41,42, GSD-Ia is characterized by fasting hypoglycemia, caused by a deficiency in G6Pase-α.1 However, it is reasonable to suggest that there are some common pathways that might be important in diabetes and GSD-Ia. Firstly, renal dysfunctions in both GSD-Ia and diabetic nephropathy exhibit a similar clinical course and pathology.5,10 Secondly, a common denominator for both diabetes and GSD-Ia is the increase in the intracellular renal levels of G6P - the intracellular form of glucose. Interestingly, the glucose-stimulated expression of Ang and TGF-β1 was mediated by the G6P metabolite diacylglycerol43, an activator of the protein kinase C transduction pathway.31,37,43 In diabetic patients, hyperglycemia leads to an increase in the renal uptake of glucose by a facilitated glucose transporter.44 The glucose is then converted efficiently to G6P by the low Km hexokinase expressed in the kidney. In GSD-Ia patients, the cause of increased G6P is different, stemming from enhanced glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis between meals. However, the net outcome is the same, the elevation of intracellular G6P. This may lead to some common consequences. Where they differ is that in the case of GSD-Ia, the increased G6P levels are maintained and compounded by the inability of the patients to hydrolyze G6P back to glucose when needed.1 As a result, the high intracellular G6P levels drive excessive glycogen accumulation in the kidney and trigger additional clinical manifestation of nephromegaly seen in GSD-Ia1 which can be observed as early as 3 days of age. This is not the case in diabetic nephropathy and clearly highlights the differences that also exist. For example, hyperglycemia associated with diabetes increases the activity of the polyol pathway, alters the redox state of pyridine nucleotides, and induces glycation of proteins, all can lead to renal damages.11 Nevertheless, an understanding of the molecular and pathological bases of diabetic nephropathy may help to provide clues to pathways that may unravel the etiology of kidney dysfunctions in GSD-Ia.

GSD-Ia patients also manifest hyperuricemia and hyperlipidemia1 which can be independent risk factors for the development and progression of renal disease. Rats with mild hyperuricemia develop interstitial renal injuries which may occur through activation of the intrarenal Ang system.29,30 Furthermore, the hyperuricemic rats developed glomerular hypertrophy, and upon prolonged hyperuricemia develop albuminuria and glomerulosclerosis.45 We have shown that serum levels of uric acid were elevated in 1-week-old GSD-Ia mice which may also activate the Ang system in GSD-Ia kidneys. Ang II acts through two 7-transmembrane-domain, G-protein coupled receptors, AT1 and AT2.33,34 In our study, we showed that renal expression of the AT1 receptor, which is implicated almost exclusively with the Ang II-mediated renal diseases15-19, was elevated in GSD-Ia mice. Mechanistically, this is quite reasonable. The expression of the AT1 receptor can be induced by hypercholesteremia and high levels of low density lipoproteins46 both clinical manifestations of GSD-Ia.1,47 Moreover, studies have shown that overexpression of the AT1 receptor in podocytes of transgenic rats results in structural podocyte damage leading to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.48

In conclusion, we have shown that renal disease in GSD-Ia is mediated, at least in part, by the Ang/TGF-β1/CTGF pathway resulting in renal fibrosis characterized by increased synthesis and deposition of ECM proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

G6Pase-α-deficient GSD-Ia mice

All animal studies were conducted under an animal protocol approved by the NICHD Animal Care and Use Committee. A glucose therapy, that consists of intraperitoneal injection of 25-100 μl of 15% glucose, every 12 h, was initiated on the first post-natal day for GSD-Ia mice, as described previously.32 Mice that survived weaning were given unrestricted access to Mouse Chow (Zeigler Bros., Inc., Gardners, PA). GSD-Ia is an autosomal recessive disorder.1 Since the phenotypes of wild-type and heterozygous mice are identical, with both exhibiting normal development and metabolic functions32, we use the designation “wild-type” to refer to both wild-type and heterozygous mice.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR, Western blot, serum, and phenotype analyses

Total RNAs were isolated from the kidneys using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The mRNA expression was quantified by real-time RT-PCR, performed in triplicates, in an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) 7300 Real-Time PCR System using the gene-specific TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays and then normalized to GADPH RNA. The TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays used were: Agt, Mm00599662_m1; AT1, Mm00558224_s1;TGF-β1, Mm00441724_m1; CTGF, Mm00515790_g1; fibronectin, Mm01256734_m1; procollagen α1(I), Mm00801666_g1; procollagen α2(I), Mm00483888_m1; procollagen α1(III), Mm00802331_m1; procollagen α2(IV), Mm00802386_m1; and GADPH, Mm99999915_g1. Data were analyzed using the SDS v1.3 software (Applied Biosystems) and expression levels normalized against the level of the appropriate transcript in a wild-type mouse, which was arbitrarily defined as 1.

For Western-blot analysis, kidney lysates were resolved by electrophoresis through a 10% polyacrylamide-SDS gel and trans-blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA). The membranes were incubated with a goat polyclonal antibody against Ang I/II (N-10), a rabbit polyclonal antibody against AT1 (N-10), a mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin; all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), or a rabbit polyclonal antibody against CTGF (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). The membranes were then incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second antibody and the immunocomplex visualized using the Immobilon™ western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore). TGF-β1 was quantified using the Quantikine Mouse/Rat/Porcine/Canine TGF-β1 Immunoassay kit obtained from R&D Systems Inc.(Minneapolis, MN).

Blood samples were collected from the tail vein, serum uric acid levels were analyzed using a kit obtained from Thermo Electron (Louisville, CO), and serum creatinine levels were analyzed using a kit obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining, tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4-6 microns thickness.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Mouse kidneys were snap frozen, embedded in O.C.T. (Sakura Finetek, Terrance, CA), and sectioned at 6 micron thickness. To identify Agt/Ang I/Ang II, TGF-β1, CTGF, and ECM proteins by immunohistochemical analysis, tissue sections were prepared by quenching the endogenous tissue peroxidases with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in 70% methanol for 30 min. The endogenous avidin/biotin was blocked using the Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). The sections were then stained with a goat polyclonal antibody to Ang I/II (N-10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a goat antibody to collagen α2(I) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a mouse monoclonal antibody to TGF-β1, or one of the rabbit polyclonal antibodies to CTGF, fibronectin, collagen α1(I), or collagen α2 (IV), all from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). The stained sections were then incubated with biotinylated anti-goat IgG, biotinylated anti-mouse IgG or biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) and the immune complexes detected using an ABC kit and DAB Substrate from Vector Laboratories according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sections were finally counterstained with hematoxylin before mounting.

Statistical analysis

The unpaired t test was performed using the GraphPad Prism Program, version 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Values were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, NIH.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chou JY, Matern D, Mansfield BC, Chen YT. Type I glycogen storage diseases: disorders of the glucose-6-phosphatase complex. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:121–143. doi: 10.2174/1566524024605798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Gierke E. Hepato-nephro-megalia glycogenica (Glykogenspeicher-krankheit der Leber und Nieren) Beitr Pathol Anat. 1929;82:497–513. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YT, Coleman RA, Scheinman JI, et al. Renal disease in type I glycogen storage disease. N. Engl J Med. 1988;318:7–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801073180102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verani R, Bernstein J. Renal glomerular and tubular abnormalities in glycogen storage disease type I. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker L, Dahlem S, Goldfarb S, et al. Hyperfiltration and renal disease in glycogen storage disease, type I. Kidney Int. 1989;35:1345–1350. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene HL, Slonim AE, O’Neill JA, Jr, Burr IM. Continuous nocturnal intragastric feeding for management of type 1 glycogen-storage disease. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:423–425. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197602192940805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YT, Cornblath M, Sidbury JB. Cornstarch therapy in type I glycogen storage disease. N. Engl J Med. 1984;310:171–175. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198401193100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein DA, Somers MJ, Wolfsdorf JI. Decreased urinary citrate excretion in type 1a glycogen storage disease. J Pediatr. 2001;138:378–382. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rake JP, Visser G, Labrune P, et al. Glycogen storage disease type I: diagnosis, management, clinical course and outcome. Results of the European Study on Glycogen Storage Disease Type I (ESGSD I) Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):S20–S34. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YT. Type I glycogen storage disease: kidney involvement, pathogenesis and its treatment. Pediatr Nephrol. 1991;5:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00852851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrijvers BF, De Vriese AS, Flyvbjerg A. From hyperglycemia to diabetic kidney disease: the role of metabolic, hemodynamic, intracellular factors and growth factors/cytokines. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:971–1010. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf G. New insights into the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy: from haemodynamics to molecular pathology. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:785–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eikmans M, Baelde JJ, de Heer E, Bruijn JA. ECM homeostasis in renal diseases: a genomic approach. J Pathol. 2003;200:526–536. doi: 10.1002/path.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. Renal fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2003;8:68–86. doi: 10.2741/925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf G. Renal injury due to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation of the transforming growth factor-beta pathway. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1914–1919. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Iwao H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klahr S, Morrissey JJ. The role of vasoactive compounds, growth factors and cytokines in the progression of renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;75(Suppl):S7–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mezzano SA, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Angiotensin II and renal fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38:635–638. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.094234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Esteban V, et al. Angiotensin II: a key factor in the inflammatory and fibrotic response in kidney diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:16–20. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guron G, Friberg P. An intact renin-angiotensin system is a prerequisite for normal renal development. J Hypertens. 2000;18:123–137. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagami S, Border WA, Miller DE, Noble NA. Angiotensin II stimulates extracellular matrix protein synthesis through induction of transforming growth factor-beta expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2431–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI117251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bottinger EP, Bitzer M. TGF-beta signaling in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2600–2610. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000033611.79556.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Jim B, Ziyadeh FN. Diabetic nephropathy and transforming growth factor-beta: transforming our view of glomerulosclerosis and fibrosis build-up. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:532–543. doi: 10.1053/s0270-9295(03)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in renal fibrogenesis: pathologic significance, molecular mechanism, and therapeutic intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1–12. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000106015.29070.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu BC, Sun J, Chen Q, et al. Role of connective tissue growth factor in mediating hypertrophy of human proximal tubular cells induced by angiotensin II. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:429–437. doi: 10.1159/000074534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta S, Clarkson MR, Duggan J, Brady HR. Connective tissue growth factor: potential role in glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ihn H. Pathogenesis of fibrosis: role of TGF-beta and CTGF. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:681–685. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan CJ, Kei KJ, Chen H, et al. Ontogeny of the murine glucose-6-phosphatase system. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;358:17–24. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2001;38:1101–1106. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.092839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang DH, Nakagawa T, Feng L, et al. A role for uric acid in the progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2888–2897. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000034910.58454.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang SL, Filep JG, Hohman TC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of glucose action on angiotensinogen gene expression in rat kidney proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int. 1999;55:454–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lei KJ, Chen H, Pan CJ, et al. Glucose-6-phosphatase dependent substrate transport in the glycogen storage disease type 1a mouse. Nat Genet. 1996;13:203–209. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, et al. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas WG, Qian H. Arresting angiotensin type 1 receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:130–136. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruilope LM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Ritz E, Luscher TF. the Cinderella of cardiovascular risk profile. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1782–1787. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01627-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urushihara M, Kagami S, Ito M, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta in renal disease with glycogen storage disease I. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:676–678. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ha H, Yu MR, Lee HB. High glucose-induced PKC activation mediates TGF-beta 1 and fibronectin synthesis by peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2001;59:463–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Luo F, Pan K, et al. High glucose upregulates connective tissue growth factor expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riser BL, Cortes P. Connective tissue growth factor and its regulation: a new element in diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Ren Fail. 2001;23:459–470. doi: 10.1081/jdi-100104729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forbes JM, Fukami K, Cooper ME. Diabetic nephropathy: where hemodynamics meets metabolism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2007;115:69–84. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-949721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castano L, Eisenbarth GS. Type-I diabetes: a chronic autoimmune disease of human, mouse, and rat. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:647–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor SI. Insulin action, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed McGraw-Hill Inc; New York: 2001. pp. 1433–1469. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evcimen ND, King GL. The role of protein kinase C activation and the vascular complications of diabetes. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leon CA, Raij L. Interaction of haemodynamic and metabolic pathways in the genesis of diabetic nephropathy. J Hypertens. 2005;11:1931–1937. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000188415.65040.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakagawa T, Mazzali M, Kang DH, et al. Hyperuricemia causes glomerular hypertrophy in the rat. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:2–7. doi: 10.1159/000066303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nickenig G, Wassmann S, Bohm M. Regulation of the angiotensin AT1 receptor by hypercholesterolaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2000;2:223–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2000.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy E, Letarte J, Lepage G, et al. Plasma and lipoprotein fatty acid composition in glycogen storage disease type I. Lipids. 1987;22:381–385. doi: 10.1007/BF02537265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann S, Podlich D, Hahnel B, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor overexpression in podocytes induces glomerulosclerosis in transgenic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1475–1487. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000127988.42710.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]