Abstract

Hair cells of the inner ear are damaged by intense noise, aging, and aminoglycoside antibiotics. Gentamicin causes oxidative damage to hair cells, inducing apoptosis. In mammals, hair cell loss results in a permanent deficit in hearing and balance. In contrast, avians can regenerate lost hair cells to restore auditory and vestibular function. This study examined the changes of myosin VI and myosin VIIa, two unconventional myosins that are critical for normal hair cell formation and function, during hair cell death and regeneration. During the late stages of apoptosis, damaged hair cells are ejected from the sensory epithelium. There was a 4–5-fold increase in the labeling intensity of both myosins and a redistribution of myosin VI into the stereocilia bundle, concurrent with ejection. Two separate mechanisms were observed during hair cell regeneration. Proliferating supporting cells began DNA synthesis 60 hours after gentamicin treatment and peaked at 72 hours postgentamicin treatment. Some of these mitotically produced cells began to differentiate into hair cells at 108 hours after gentamicin (36 hours after bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) administration), as demonstrated by the colabeling of myosin VI and BrdU. Myosin VIIa was not expressed in the new hair cells until 120 hours after gentamicin. Moreover, a population of supporting cells expressed myosin VI at 78 hours after gentamicin treatment and myosin VIIa at 90 hours. These cells did not label for BrdU and differentiated far too early to be of mitotic origin, suggesting they arose by direct transdifferentiation of supporting cells into hair cells.

Indexing terms: aminoglycoside ototoxicity, bromodeoxyuridine, transdifferentiation, unconventional myosins

Hair cells are the mechanoreceptors in the inner ear responsible for the senses of hearing and balance. They have a bundle of 20–300 actin-rich membrane-encased projections on their apical surface called stereocilia. The stereocilia are embedded in a dense actin-rich meshwork below the luminal surface of the hair cell called the cuticular plate. Sound is transferred into fluid-waves in the inner ear that deflect the stereocilia, thereby opening transduction channels. The potassium-rich endolymph enters the hair cell, changing the potential of the cell and triggering a neural impulse in the afferent nerves at the bases of the hair cells (reviewed in Hackney and Furness, 1995; Corey, 2003). The structure of the avian auditory sensory epithelium is different from the mammalian cochlea in that it lacks the distinct rows of inner and outer hair cells, distinguishable types of supporting cells, and characteristic spiral shape.

The structure and function of the sensory hair cells, however, are highly conserved across species, making the avian ear a useful tool for studying hearing. Aging, genetic mutations, environmental stresses, and exposure to ototoxic agents can damage hair cells. In some cases an apoptotic signaling pathway is activated to kill the damaged hair cells while maintaining the health of the sensory epithelium (Cheng et al., 2003, 2005; Mangiardi et al., 2004). In the avian ear, apoptotic hair cells are ejected from the sensory epithelium, unlike the phagocytotic mechanism operating in other tissue types (Hirose et al., 1999, 2004; Rosenblatt et al., 2001; Mangiardi et al., 2004). In mammalian vertebrates, cochlear hair cell loss is permanent, causing irreversible hearing deficits. In contrast, the hair cells found in the avian cochlea have the capacity to regenerate. Following hair cell death, the normally quiescent supporting cells in the avian cochlea proliferate and the daughter cells differentiate into new hair cells and supporting cells, indicating that there is an inextricable link between hair cell death and regeneration (reviewed in Cotanche, 1999; Bermingham-McDonogh and Rubel, 2003; Matsui and Cotanche, 2004). Previous studies have indicated that new hair cells may arise through the direct transdifferentiation of supporting cells into hair cells, without going through mitosis in both amphibian (Baird et al., 1993, 1996) and avian models (Adler and Raphael, 1996; Roberson et al., 1996, 2004).

In the current study, we examined the distribution of myosin VI and VIIa during the process of hair cell death and regeneration. Myosins are a family of motor proteins that move along actin filaments in a cell. Myosin VI and myosin VIIa are nonmuscle myosins that are unique to the sensory hair cells within the inner ear. Several roles for myosin VI in hair cells have been proposed including anchoring the cell membrane between the individual stereocilia (Self et al., 1999), maintaining the integrity of the apical surface of the cell (Seiler et al., 2004), mediating endocytosis in the sensory receptor (reviewed in Buss et al., 2002), and interacting with E-cadherin in adhesion complexes (Geisbrecht and Montell, 2002). Myosin VIIa interacts with other proteins including sans, vezatin, protocadherin 15, and cadherin 23, which are critical to hair cell function (reviewed in Adato et al., 2005), and has further been implicated in aminoglycoside uptake (Richardson et al., 1997, 1999). Mutations of the genes encoding myosin VI and VIIa cause defects in hair cell morphology, causing profound deafness in both mice and humans (reviewed in Redowicz, 2002).

Myosin VI and VIIa increased in labeling intensity when hair cells were in the process of being ejected from the sensory epithelium, and remained in the tectorial membrane above the gentamicin damage lesion (preliminary results reported in Duncan et al., 2004). The current study characterizes the changes in myosin VI and myosin VIIa labeling that occur during hair cell ejection. The study also outlines the events of hair cell regeneration as they occur in both mitotic and nonmitotic, via direct trans-differentiation, generation of hair cells. More specifically, the data show two distinct timelines of regeneration through offset expression of hair cell-specific proteins during hair cell differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

White leghorn chickens (Gallus domesticus) were obtained at either 7 or 14 days after hatching (Charles River SPAFAS, Preston, CT) and housed in the animal research facility at Children’s Hospital, Boston. The Children’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all animal treatment procedures, which conform to US government regulations.

Drug administration and tissue dissection

Chicks 11–15 days posthatch received a single subcutaneous injection of gentamicin sulfate (300 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at time “0 hours.” Chicks were injected in the morning to allow the nephrotoxic effects of the gentamicin to pass before night (Roberson et al., 2000). Age-matched, untreated control animals were used in parallel. To document the changes in the distribution of myosin VI and VIIa in hair cells undergoing apoptosis, the chicks were sacrificed at 24, 36, 40, 42, 48, or 72 hours, or 4, 5, 6, 10, or 14 days after receiving the injection of gentamicin.

To study the differentiation of hair cell precursors into hair cells, chicks were sacrificed at 72, 78, 84, or 90 hours, or 4, 5, or 6 days. Some birds received a single, subcutaneous injection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 100 mg/kg in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4; Sigma) at either 54, 60, 65, 72, or 78 hours, or 4, 5, or 6 days following the single injection of gentamicin and then sacrificed 4 hours after receiving the BrdU in order to determine the relative rates of mitosis. A final set of birds received a single injection of BrdU at 72 hours after receiving gentamicin. These birds were sacrificed 24, 36, or 48 hours later to determine when the progenitor cells of mitotic origin begin to express hair cell-specific proteins.

The chicks were euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of Fatal-Plus (390 mg/mL pentobarbital; Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI). The cochlear ducts were quickly dissected using the Oberholtzer et al. (1986) technique, and the tegmentum vasculosum was removed from the basilar papilla in an ice-cold, HEPES-buffered Hank’s balanced salt solution, pH 7.4 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). The papillae were then fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour, thoroughly washed with PBS, and stored in PBS at 4°C.

Immunohistochemistry

To study the changes in myosin expression during the process of hair cell death and regeneration, cochleae were labeled with antibodies directed against myosin VI and myosin VIIa. Antibodies directed against β-III tubulin were used as another early marker of hair cell differentiation (Molea et al., 1999; Matsui et al., 2000; Stone and Rubel, 2000). All incubations were performed at room temperature, with PBS washes between steps, and protected from direct light unless otherwise stated. After fixation the papillae were permeabilized in a solution of 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS for 10 minutes. The tissue was then blocked with a 10% normal goat serum solution in PBS and immediately incubated in the appropriate primary antibody solution (10 μg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours. The primary antibodies were mouse anti-β-III tubulin (1:200; G7121; Promega, Madison, WI), rabbit anti-pig myosin VI, and rabbit antihuman myosin VIIa (1:100; Tama Hasson, UCSD, La Jolla, CA; Available as 25-6791 and 25-6790, respectively; Proteus Biosciences, Ramona, CA). The papillae were then incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antirabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000; A-11008; Molecular Probes division of Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 2 hours. Ears that were double-labeled with rabbit anti-myosin and mouse anti-β-III tu-bulin antibodies were incubated with both Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antirabbit (1:1,000) and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat antimouse antibodies (1:1,000; A-11004; Molecular Probes). Some ears were counter-stained with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated phalloidin (1: 100; A12380; Molecular Probes) for 30 minutes to visualize the f-actin in the stereocilia bundles, while other ears were counterstained with To-Pro-1 or To-Pro-3 Iodide (1: 2,000; Cat. nos. T3602 and T3605, respectively; Molecular Probes) for 10 minutes to visualize the nuclei. The papillae were then mounted on glass slides in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

In order to study the progression of DNA synthesis in supporting cells during regeneration, cochlear explants were double-labeled with antibodies directed against BrdU and either myosin VI or myosin VIIa (Roberson et al., 2000). The fixed cochleae were permeabilized and their DNA was denatured in a solution consisting of 1% Triton-X 100 made in 2N HCl for 25 minutes at 37°C and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum solution in PBS for 10 minutes. Cochleae were then immediately incubated in a primary antibody solution containing one of the rabbit anti-myosin antibodies and the mouse anti-BrdU antibody (1:100; Cat. no. 347580; Becton-Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). The ears were then incubated in Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antirabbit (1:1,000; Molecular Probes) and Alexa Fluor 568 goat antimouse (1:1,000; Molecular Probes) secondary antibodies and then mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

Polyclonal antibodies against myosin VI were raised in rabbits immunized with a peptide corresponding to amino acids 1049–1054 from the tail region of porcine myosin-VI. The antibodies were affinity-purified and identified a single 140-kD band of a Western blot of chicken liver (Hasson and Mooseker, 1994). The antibody labeled only the bodies of hair cells in the chick basilar papilla, expressing the classical myosin VI distribution (Hasson and Mooseker, 1994). Affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against myosin VIIa were raised in rabbits immunized with a peptide corresponding to amino acids 880–1077 from the tail region of human myosin-VIIa. The antibodies displayed the classical hair cell-specific labeling distribution (Hasson et al., 1995; Bermingham-McDonogh et al., 2006) and identified a single band of ~220 kDa in a blot of rat cochlear tissue (Hasson et al., 1995). The monoclonal β-III tubulin antibodies were raised against a synthetic peptide EAQGPK, corresponding to the c-terminus of the β-III tubulin protein. Promega technical documents indicated that the antibody labeled only neuronal cells in a mixed culture of glial and neuronal cells (Gillessen et al., 2000) and directed us to an article demonstrating that the antibody labeled a single band of protein ~59 kDa in mass in blots of mouse brain (Spittaels et al., 2000). The antibody displayed the expected distribution of labeling seen with other β-III tubulin antibodies in the chick cochlea (Stone and Rubel, 2000). BrdU antibodies did not label samples taken from animals that were not treated with BrdU. In BrdU-treated animals the antibody matched the classic distribution by strongly labeling some larger nuclei within the supporting cell layer under the gentamicin damage lesion (presumably in S-phase), while it did not label other supporting cells or supporting cells outside of the damaged region.

Imaging

Compressed z-series images were taken using a Leica TCS SP confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany) using 20×, 40×, and 100× objectives. The images were then assembled, labeled, and scale bars added using Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). After the myosin channel was isolated, Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to outline ejected and healthy hair cells in the same images in order to normalize for intrinsic variations in signal between images. To quantify the increase in myosin labeling intensity, average luminosity measurements were taken of 10 healthy and 10 ejected hair cells within each image, and the average ratio of healthy to ejected luminosity was calculated for each image.

For BrdU-treated birds, a series of confocal stack images were taken of the damaged region of whole-mount preparations of the basilar papilla at 40× optical magnification. The images were overlapped and assembled into a single montage image using Adobe Photoshop at a resolution of 72 pixels per inch. Each montage was cropped to include the damaged region of the basilar papilla and placed in a 4000 by 6000 pixel image with a white background for further analysis with a semiautomated counting program.

Semiautomated counting program and statistical methods

To monitor the progression of S-phase during hair cell regeneration, each BrdU-labeled nucleus was marked using the crosshair tool in Image J. A MATLAB script (MathWorks, Natick, MA) was written to determine the number of BrdU-labeled nuclei within each montage image of the sensory epithelium after 4 hours of BrdU exposure. Stereological counting methods were not appropriate for our imaging technique because employing confocal microscopy of whole-mounted tissue samples, we were able to identify all BrdU-positive nuclei within a sample, eliminating the inherent error arising from the serial sectioning process. All statistics were performed using SPSS v. 10.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Samples were paired by the image from which they were taken. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for the total number of BrdU-labeled nuclei at each time point to determine the time-dependent nature of DNA synthesis. A Sida′ k multiple comparison was performed post hoc to show if there was a significant peak in mitotic activity.

For measurements of differences in labeling intensity for myosins VI and VIIa, a paired-samples t-test was performed to compare the differences between the mean myosin labeling signal intensity of undamaged and apoptotic hair cells.

RESULTS

Distribution of myosin VI and VIIa in control tissue

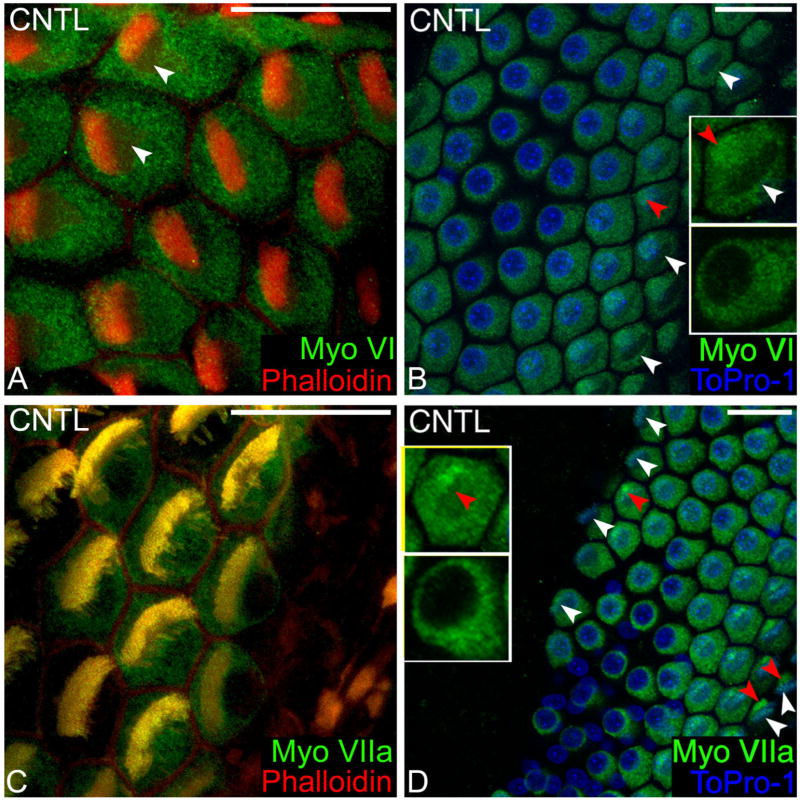

Antibodies directed against myosin VI labeled the cytoplasm of hair cells in the basilar papilla but not the surrounding supporting cells (Fig. 1A). Myosin VI was highly concentrated in the pericuticular necklace, a small region around the cuticular plate on the apical surface of the hair cell. Myosin VI was excluded from the cuticular plate, stereocilia bundle (Fig. 1B, upper inset), and supporting cells (Fig. 1B) and was not found within the nucleus, where there was a sharp, distinct border between the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 1B, lower inset). Myosin VIIa was uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, highly concentrated in the pericuticular necklace, cuticular plate, and stereocilia bundle (Fig. 1C) but was excluded from the nucleus and supporting cells (Fig. 1D, inset).

Fig. 1.

Normal distribution of myosin VI and VIIa in hair cells. A: Myosin VI (green) is uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of avian hair cells, but is excluded from the actin (red) rich cuticular plate (white arrowhead) and stereocilia bundle. B: The exclusion of myosin VI (green) becomes even more apparent in the absence of phalloidin labeling of the stereocilia bundle and cuticular plate (white arrowhead, upper inset), as does the concentration within the pericuticular necklace (red arrowhead, upper inset) and exclusion from the nucleus (blue). The blue To-Pro channel is removed in the lower inset. C: Myosin VIIa (green) is distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm and within the stereocilia bundle and the cuticular plate. Yellow indicates that the green and red fluorophores are colocalized. D: Myosin VIIa labeling (green) allows the stereocilia bundle to be seen without phalloidin staining (white arrowheads), as can the pericuticular necklace concentration (red arrowheads, upper inset), and nuclear exclusion (blue). The blue To-Pro channel was removed in the lower inset. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Changes of the distribution of myosins upon hair cell ejection

A single gentamicin injection initiates an apoptotic-signaling cascade in the chick cochlear sensory hair cells (Mangiardi et al., 2004). Coincident with the execution phase of apoptosis, the damaged hair cells were ejected out of the epithelium by the surrounding supporting cells using a process called “blebbing.” The first blebbing hair cells were observed 36 hours after gentamicin injection, with the majority of damaged cells ejected by 48 hours. By studying the changes to hair cell-specific proteins during apoptosis, we tracked the fate of the dying hair cells as well as the changes to the cellular composition of the damaged sensory epithelium.

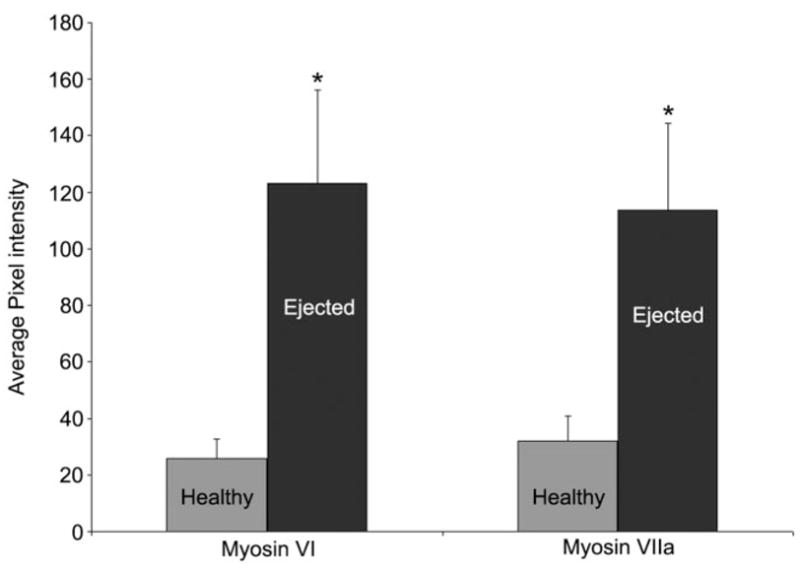

When dying hair cells were ejected from the sensory epithelium, there was an increase in the labeling intensity of myosin VI (Fig. 2). There was no change in the intensity of myosin VI prior to blebbing while the hair cell remained integrated in the epithelial mosaic. Myosin VI labeling in ejected hair cells was determined to be 4.9 ± 1.2 times brighter in surviving hair cells in the same images taken 42 hours after gentamicin injection (n = 10 cells for each condition per image, six images). A paired-samples t-test indicated that the labeling intensity of myosin VI was significantly brighter in the ejected cells than the remaining “surviving” hair cells (P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Change in myosin labeling intensity. A graph representing the average labeling intensity of 10 healthy and 10 ejected hair cells taken within images containing both healthy and ejected hair cells. Six images of myosin VI-labeled cochleae and five images of myosin VIIa-labeled cochleae, each taken 42 hours after gentamicin treatment were examined. *Statistical significance at P < 0.01 for the paired-samples t-test. Bars = standard deviation.

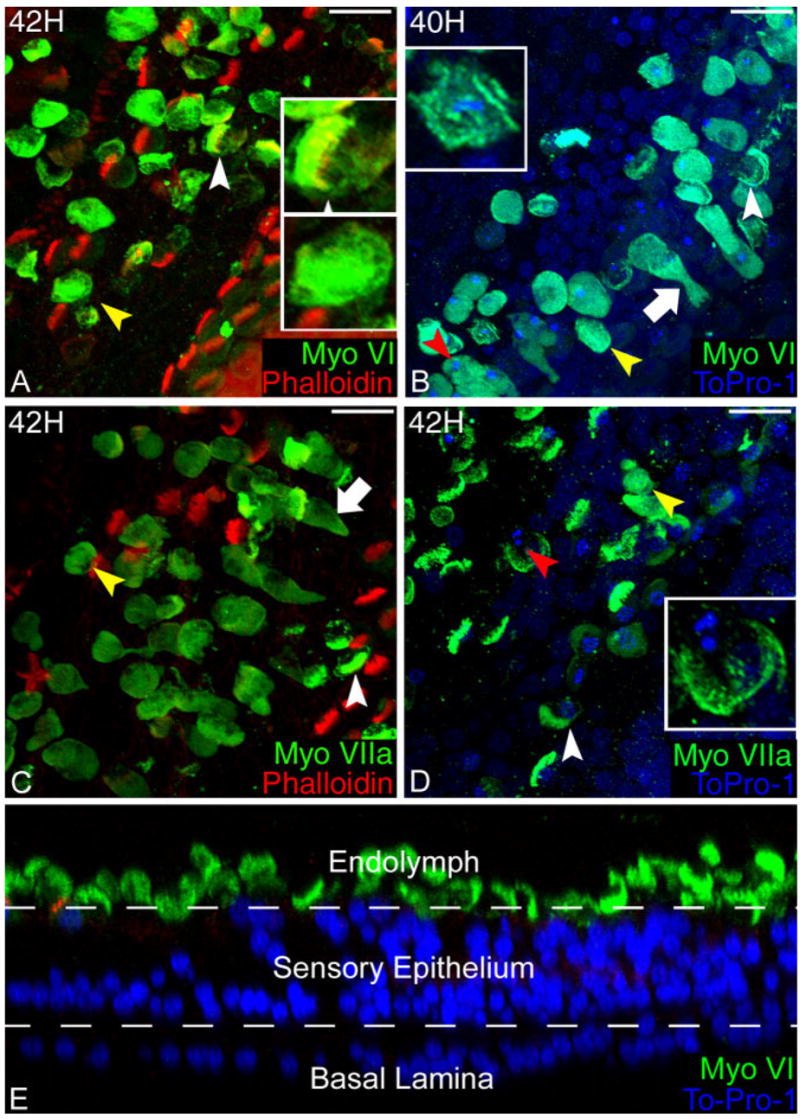

Following ejection, some cell bodies retained a “hair cell-like” morphology in which the stereocilia were prominently visible when labeled with myosin VI (Fig. 3A, upper inset). In these cells, the myosin VI labeling was redistributed throughout the cell, including into the stereocilia bundle, where it was previously excluded (Fig. 3A, upper inset). Even though the stereocilia bundles were readily identifiable in some of the ejected hair cells bodies by myosin VI labeling, phalloidin, an f-actin stain, failed to label the stereocilia bundles shortly after their ejection from the sensory epithelium (Fig. 3A, upper inset). This suggests that either pH changes in the dying hair cells or changes in the f-actin molecules were making them unable to bind phalloidin (De La Cruz and Pollard, 1996; Mangiardi et al., 2004). The other ejected cells assumed a “globular” morphology, where the myosin labeling had a uniform intensity throughout the cytoplasm and the stereocilia bundles were not identifiable (Fig. 3A, lower inset). Ejected hair cells had condensed chromatin and smaller, pyknotic nuclei when compared to untreated controls. The nuclei of many hair cells in the damaged region became increasingly condensed and fragmented as the cells were ejected from the sensory epithelium (Fig. 3B, inset). The cytoplasmic labeling of myosin VI surrounded the pyknotic nuclei within ejected cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Changes in the distribution of myosin VI and VIIa in dying hair cells. A: Myosin VI (green) labeling increases in intensity upon ejection from the sensory epithelium. Two morphologies are observed in the cell bodies being ejected from the sensory epithelium: “hair cell-like” (white arrowhead) and “globular” (yellow arrowhead). In the hair cell-like morphology (upper inset), myosin VI is expressed in the stereocilia bundle (yellow) where it was previously excluded. In the globular morphology (lower inset), myosin VI is uniformly distributed and intensely labels the body of the ejected cell. B: Both hair cell-like (white arrowhead) and globular (yellow arrowhead) label with myosin VI (green), as do blebbing hair cells (white arrow) that increase their labeling intensity during the ejection process. Pyknotic nuclei (blue) (red arrowhead and inset), a hallmark of apoptotic death, are found in the ejected hair cells (green). C: Myosin VIIa labeled (green) preparations have the same mixture of hair cell-like (white arrowhead) and globular (yellow arrowhead) morphologies. Blebbing hair cells (white arrow) can be seen increasing their intensity upon ejection from the sensory epithelium. D: Pyknotic nuclei (blue) (red arrowhead and inset) can be seen in myosin VIIa-labeled hair cells that have been ejected from the sensory epithelium within both ejected hair cell morphologies (yellow and white arrowheads). E: Confocal cross section of the damaged sensory epithelium 72 hours after gentamicin. Following apoptosis, hair cells in the proximal end of the cochlea are ejected from the sensory epithelium. An optical cross section reveals that there are no myosin VI-labeled hair cells remaining in the gentamicin-damaged lesion and that the nuclear material is no longer present in any of the ejected hair cells 72 hours after gentamicin treatment. Scale bars = 10 μm.

A similar change in the labeling intensity of myosin VIIa was observed upon hair cell ejection (Fig. 2). As with the myosin VI labeling, there was no change to the myosin VIIa labeling prior to blebbing. In images collected 42 hours after gentamicin treatment, myosin VIIa labeling in ejected hair cells increased 3.8 ± 1.2-fold (n = 10 cells for each condition per image, five images) over hair cells remaining in the sensory epithelium. A paired-samples t-test indicated that the labeling intensity of myosin VIIa was significantly brighter in the ejected cells than the remaining “surviving” hair cells (P < 0.01). Myosin VIIa was expressed throughout the entire stereocilia bundle, and the labeling intensity strongly increased throughout the cytoplasm in blebbing cells as they were forced out of the sensory epithelium (Fig. 3C, arrowheads) and the cell bodies remained brightly labeled in the endolymph fluid (Fig. 3C). Both the hair cell-like and globular morphologies of ejected hair cells, described earlier for myosin VI, were also observed with myosin VIIa labeling. Furthermore, myosin VIIa labeling also filled the newly created cytoplasmic space left by the shrinking pyknotic nuclei in the ejected cells (Fig. 3D).

After the conclusion of the apoptotic program, 54 hours after gentamicin treatment, the damaged sensory epithelium appeared vastly different from the healthy cochlea. There was complete ablation of all hair cells in the proximal 2000 μm of the sensory epithelium following a single 300 mg/kg dose of gentamicin (Fig. 3E). The most prominent features of the damaged sensory epithelium were the lack of both myosin VI and myosin VIIa labeling in the sensory epithelium as well as the absence of the prominent stereocilia bundle projections on the apical surface in addition to the absence of the regularly spaced hair cell nuclei. This indicated that all of the damaged hair cells were ejected from the proximal 30% of the sensory epithelium, leaving no damaged, surviving hair cells behind, in agreement with previous SEM/TEM studies (Cotanche, 1987; Stone and Cotanche, 1994; Janas et al., 1995; Husmann et al., 1998; Hirose et al., 1999, 2004). The remaining supporting cells sealed the lesions left by the ejected hair cells, causing an irregular pattern of phalloidin staining of the microvilli lining the adherens junctions between the supporting cells and irregularly arranged supporting cell nuclei. Even after the hair cells were ejected, the hair cells continued down the apoptotic pathway by degrading their nuclear material. Pyknotic nuclei in various stages of degradation were visible until 72 hours after gentamicin in the space above the luminal surface of the basilar papilla. After 72 hours, no nuclear remnants were observed in the ejected cells (Fig. 3E). Nevertheless, the ejected hair cells that formerly populated the surface of the epithelium continue to label with myosin VI and VIIa in the tectorial membrane 3 weeks later, long after their ejection (data not shown).

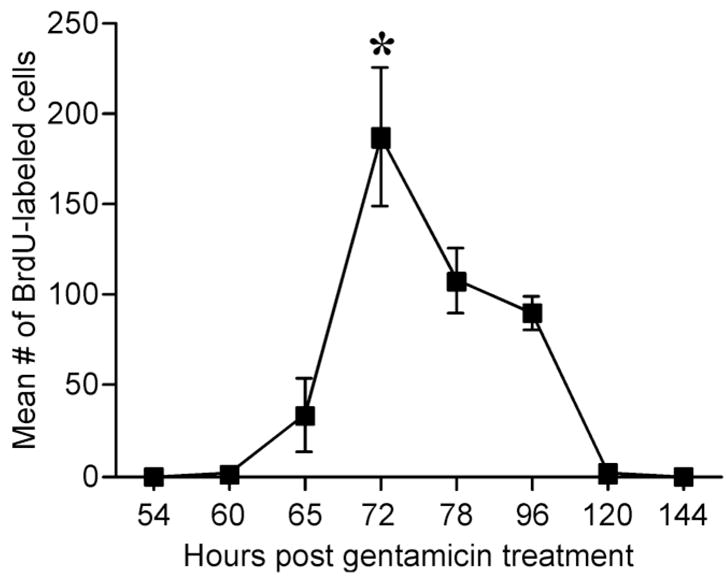

Mitotic regeneration of hair cells

The changes to the sensory epithelium resulting from gentamicin damage induced the normally quiescent supporting cells to reenter the cell cycle in order to repopulate the depleted sensory epithelium. In order to measure the relative rate of DNA synthesis, a single injection of BrdU was administered at several times after gentamicin to track cells synthesizing DNA. The BrdU exposure was limited to 4 hours in order to minimize the number of BrdU-positive nuclei arising from mitotic division. No BrdU-labeled nuclei were observed at 54 hours after gentamicin treatment (n = 4). Samples taken at 60 hours showed few BrdU-labeled cells (1.4 ± 0.4, n = 13), while more BrdU-labeled nuclei were observed at 65 hours (34 ± 20, n = 8). Neither sample was statistically different than the control group, however (P > 0.5). There was a sharp increase in the number of BrdU-labeled nuclei at 72 hours (187 ± 38, n = 13), but this included a wide range of values (10–520). The number of BrdU-labeled nuclei decreased at 78 hours (108 ± 18, n = 6) and dropped further at 96 hours (90 ± 9, n = 12). There were significantly fewer BrdU-labeled nuclei at 120 hours (2 ± 1, n = 4) when compared to the 72-hour samples and no BrdU-labeled nuclei were observed by 144 hours (n = 4) (Fig. 4). A one-way ANOVA revealed that the number of BrdU-positive nuclei depended on time (P < 0.005). A Sida′ k multiple comparisons test revealed that the peak at 72 hours was significantly higher than all other points (P < 0.005), except for the 78-hour time point (P = 0.424).

Fig. 4.

Graph of the number of BrdU-labeled nuclei after a 4-hour exposure. A single injection of gentamicin was administered at time = 0 hours. A single injection of BrdU was administered at the time indicated on the chart and the birds were sacrificed 4 hours later when the basilar papillae was removed from the animal, fixed, and processed for BrdU immunohistochemistry. A BrdU injection given 54 hours after gentamicin did not label any nuclei in the sensory epithelium. BrdU administered at 60 hours showed a few single-labeled nuclei, marking the beginnings of S-phase. The BrdU uptake increased at 65 hours and rapidly peaked at 72 hours. DNA synthesis slightly declined at 78 hours and continued to decline until reaching control levels at 120 hours. 72 hours was the statistically significant peak of BrdU uptake, indicated by the asterisk. *Significance at P < 0.01.

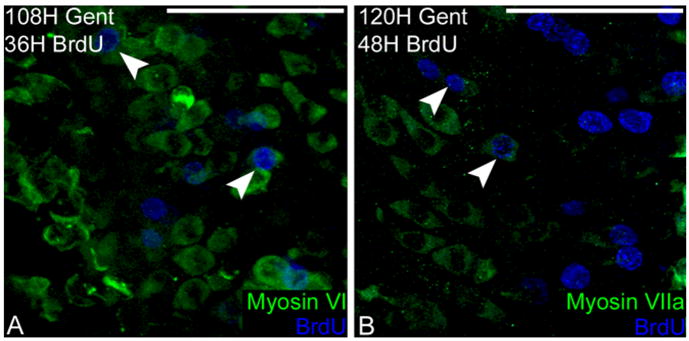

The daughter cells from the proliferating supporting cells can either become supporting cells or new hair cells (Stone and Cotanche, 1994; Corwin and Cotanche, 1998; Stone and Rubel, 2000). To determine the fate of the mitotically produced cells, a single injection of BrdU was given at 72 hours, the peak of DNA synthesis, and the birds were sacrificed at later time points. The papillae were then double-labeled with antibodies against BrdU and either myosin VI or myosin VIIa. The first cells that were double-labeled for myosin VI and BrdU appeared 108 hours after gentamicin treatment, 36 hours after BrdU uptake (Fig. 5A). The colabeled cells had a pear-shaped morphology similar to a normal supporting cell. The nuclei were located toward the bottom of the cells’ cytoplasmic space and each cell had a cellular process extending to the luminal surface of the sensory epithelium. Myosin VIIa and BrdU colocalization was first observed at the 120-hour time point in cells with a similar morphology to the cells labeling with myosin VI and BrdU (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Mitotic hair cell regeneration. A: Myosin VI (green) and BrdU (blue) first colabel in regenerating hair cells 36 hours after BrdU administration (white arrowheads). B: Myosin VIIa (green) is first coexpressed with BrdU (blue) 48 hours after BrdU uptake in the cell (white arrowheads), 12 hours later than myosin VI is expressed in mitotic cells. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Nonmitotic regeneration of hair cells

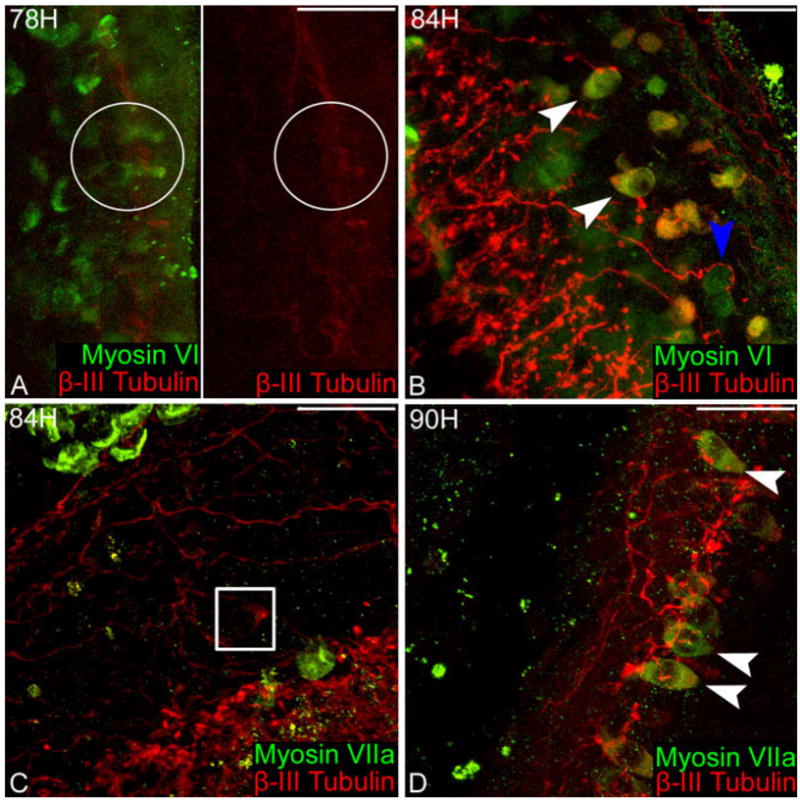

Interestingly, there was a population of sensory epithelial cells that were labeled with hair cell-specific proteins well before BrdU colabeled cells were observed. Although the phenomenon of direct transdifferentiation has been previously described (Baird et al., 1993, 1996; Adler and Raphael, 1996; Roberson et al., 1996, 2004), it is not well characterized. The first signs of supporting cells transdifferentiating into hair cells were observed at 78 hours after gentamicin, in the form of uniform myosin VI labeling in the cytoplasm of some sensory epithelial cells (Fig. 6A, left). None of the new hair cells expressed the early hair cell differentiation marker β-III tubulin (n = 8 ears) or myosin VIIa (n = 8 ears) at this time point (Fig. 6A, right). There were only a few transdifferentiating cells found in each ear at 78 hours and these immature hair cells had morphologies similar to the “intermediate morphology” described by Roberson et al. (2004) and the mitotically regenerating hair cells described above. Confocal analysis revealed a relatively small apical surface area and nuclei lying further below the luminal surface of the sensory epithelium than the nuclei of mature hair cells. Mature stereocilia bundles were not visible and the cell apices resembled the microvilli on the surface supporting cells (data not shown). At 84 hours after gentamicin treatment many of the new hair cells expressed both β-III tubulin and myosin VI (n = 6) (Fig. 6B), but not myosin VIIa (n = 6) or BrdU (Fig. 6C). By 90 hours postgentamicin treatment, myosin VIIa (n = 9) was expressed in the differentiating hair cells along with myosin VI (n = 8) and β-III tubulin (n = 9) (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Nonmitotic hair cell regeneration. A: Left, myosin VI (green) is the first hair cell-specific protein expressed in regenerating hair cells (white circle) 78 hours after gentamicin administration. β-III tubulin (red) is not expressed at 78 hours in regenerating hair cells, as demonstrated by the absence of a signal in the red-channel (white circle). B: β-III tubulin (red) colabels some cells expressing myosin VI (green) at 84 hours after gentamicin (white arrowheads), while other some hair cells only display myosin VI (blue arrowhead). C: Myosin VIIa (green) is not expressed in regenerating hair cells containing β-III tubulin (red) (white box). D: Myosin VIIa (green) is first expressed in regenerating hair cells 90 hours after gentamicin injection, colabeling with β-III tubulin (red) (apices of cells indicated by white arrowheads). Scale bars = 100 μm.

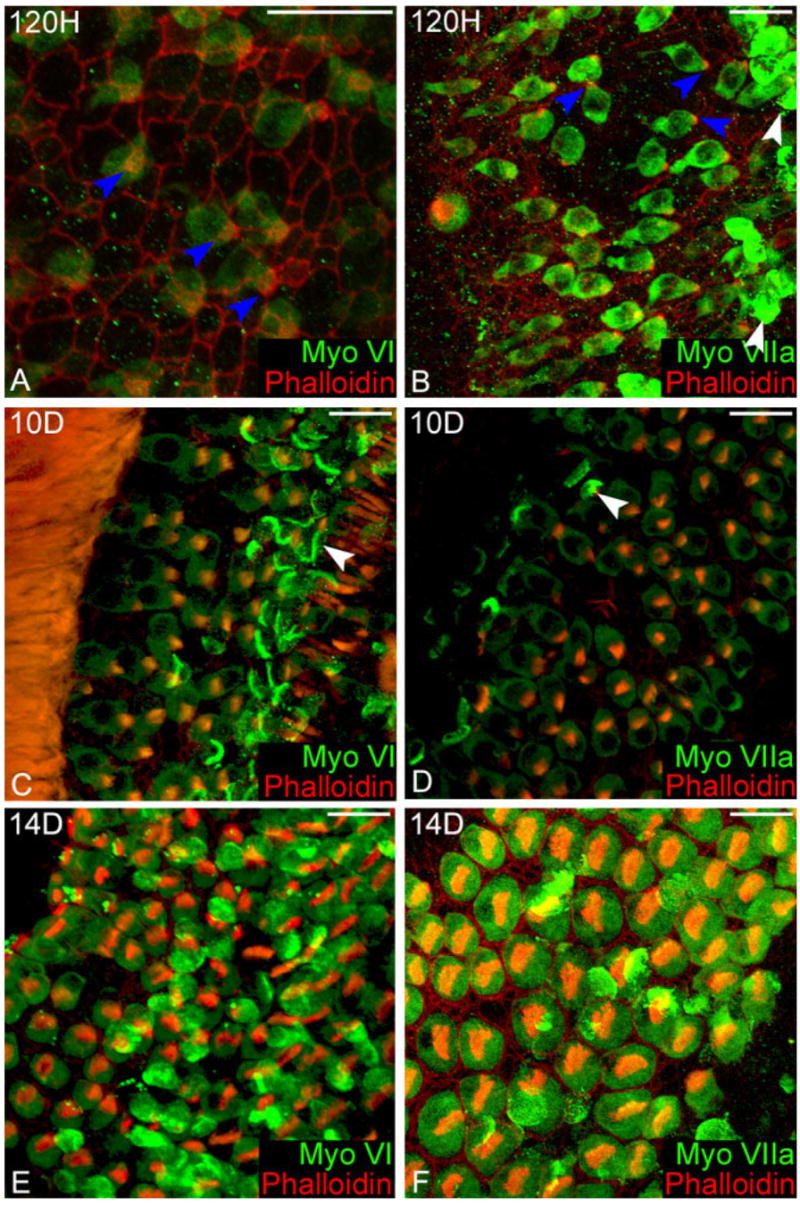

Maturation of the hair cells

By 5 days (120 hours) after gentamicin treatment the regenerating hair cells had noticeably greater volume and had larger but still immature stereocilia bundles, causing the apical surface of the cell to expand in order to compensate. Myosin VI was uniformly labeled throughout the cytoplasm. Very limited myosin VI labeling was found in the stereocilia bundle (Fig. 7A) and the cuticular plate was not visible. Myosin VIIa was uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm and intensely labeled the stereocilia bundle (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Distribution of myosin VI and VIIa in regenerating hair cells. A: 120 hours after gentamicin, myosin VI (green) is expressed at the bases of the stereocilia bundles (blue arrowheads) and throughout the cell body, but is excluded from the nucleus. The shape of the regenerating immature hair cells resemble supporting cells, with their large cell body tapering up to a very small apical surface. B: At the same time point, myosin VIIa is strongly expressed in the new hair cells and is present in the immature stereocilia bundles (blue arrowheads). Myosin VIIa is excluded from the nucleus as the circular hole in the labeling located within the body of the cell. Ejected cells caught in the tectorial membrane hover above the sensory epithelia (white arrowheads). C: 10 days after treatment, immature hair cells more closely resemble mature hair cells. The stereocilia bundles of the immature hair cells in this region are disorganized and are less dense than the surviving region. Ejected hair cells are still observed in the tectoral membrane over both the regenerating and surviving hair cells (white arrowheads). D: A higher magnification of a hair cell expressing myosin VIIa image showing the lesser degree of organization and density seen in new hair cells. Myosin VIIa is clearly expressed in the stereocilia bundles of the new hair cells, and in the ejected hair cells caught in the tectorial membrane (white arrowhead). E: Myosin VI no longer labels the stereocilia of regenerating hair cells 14 days after gentamicin. F: The distribution of myosin VIIa in regenerating hair cells is nearly identical to mature hair cells. Scale bars = 20 μm.

At 10 days postgentamicin treatment, the regenerating hair cells continued to expand their apical surfaces and the stereocilia bundles continued to mature into a characteristic staircase pattern. Myosin VI was uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm in the regenerating hair cells and the intensity was equal to the surviving hair cells, and myosin VI was still expressed in the stereocilia bundle (Fig. 7C). The stereocilia bundles of regenerating hair cells were not labeled as intensely with myosin VIIa as the surviving hair cells (Fig. 7D).

By 14 days postgentamicin treatment the distribution of myosins VI and VIIa in the developing hair cells resembled a mature hair cell. The cytoplasmic labeling of myosin VI remained uniform; however, the labeling in the stereocilia and cuticular plate was no longer observed (Fig. 7E). The uniform cytoplasmic labeling for myosin VIIa remained brighter in the regenerating cells than the surviving hair cells. The pericuticular necklace did not display the brighter labeling seen in mature hair cells; however, the cuticular plate was visible with phalloidin staining (Fig. 7F).

DISCUSSION

Changes upon hair cell ejection

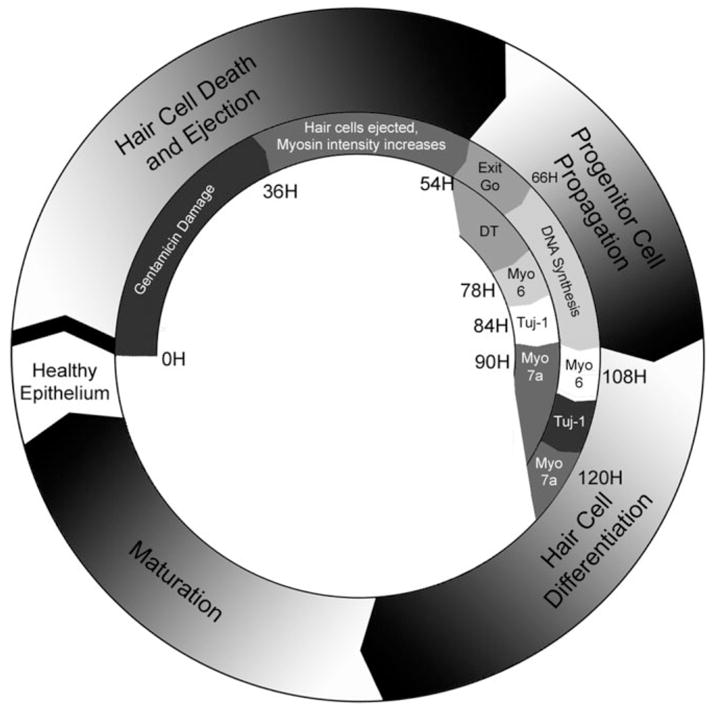

It is helpful to consider the changes of myosin labeling, summarized in Figure 8, in the context of apoptotic cell death. The main goal of apoptosis is to dispose of damaged or excess cells in a manner that controls their toxic contents. In the cochlea, disposal of gentamicin-damaged hair cells is accomplished by ejecting the dying cells from the sensory epithelium into the endolymph and tectorial membrane. The myosin labeling data reveals intact hair cell bodies containing both cytoplasmic and nuclear components being extruded from the sensory epithelium, in accord with previous studies of f-actin labeling (Mangiardi et al., 2004) and SEM/TEM data (Cotanche, 1987; Stone and Cotanche, 1994; Janas et al., 1995; Husmann et al., 1998; Hirose et al., 1999, 2004). The ejected cells caught in the tectorial membrane continue down the apoptotic pathway, as observed by the digestion of pyknotic nuclei for several hours following ejection, visible until 72 hours after gentamicin. Apparently, the ejected cell bodies do not pose a threat to the health of the epithelium, as they continue to label for myosins VI and VIIa for 21 days after gentamicin and with cytochrome oxidase for 40 days after gentamicin (Mangiardi et al., 2004).

Fig. 8.

Timeline. The outer circle of the diagram represents the major events of gentamicin-mediated hair cell death and regeneration in the avian cochlea. The inner circle describes the events observed in the current study. Beginning 36 hours after a single injection of gentamicin, and lasting through 54 hours after injection, dying hair cells undergoing apoptosis are ejected from the sensory epithelium. Shortly thereafter, the supporting cells in the damaged region of the cochlea either enter into the cell cycle or directly transdifferentiate into hair cells through nonmitotic means. The first signs of DNA synthesis occur at 66 hours after gentamicin treatment, which continues through 120 hours after gentamicin treatment. The first new myosin VI-labeled hair cells were detected 78 hours after gentamicin treatment; however, those hair cells are not BrdU-labeled, indicating that they did not arise from a mitotic origin. β-III tubulin and myosin VIIa are expressed in regenerating hair cells at 84 and 90 hours after gentamicin treatment, respectively. The first BrdU and myosin VI colabeled cells appear 36 hours after the cells enter DNA synthesis, while myosin VIIa appears 12 hours later, preserving the progression of myosin expression in hair cell differentiation.

There was an increase in the myosin labeling intensity when hair cells were ejected from the sensory epithelium, which conveniently reveals the location of the gentamicin damage lesion. Perhaps the changes in myosin labeling arose through an active mechanism. For example, upregulation of unconventional myosin levels in dying hair cells may be the cause of the increase in labeling intensity. Rosenblatt et al. (2001) demonstrated that epithelial cells undergoing apoptosis are ejected from their epithelium in a myosin-actin-dependent manner. Changes in unconventional myosin labeling described in the current study may be part of a similar mechanism active in hair cell ejection. Nevertheless, neither myosin VI nor myosin VIIa has been implicated in any apoptotic-signaling pathway. From a practical standpoint, synthesizing large quantities of both of these motor proteins, to reflect the increase in intensity, would be inefficient. A quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of myosin mRNA levels could provide insight into this possibility.

A more likely explanation for the change in intensity may arise from changes in the activity of the myosin molecules. The primary antibodies used in this study were raised against the entire tail of myosin VI (Hasson et al., 1994) and against amino acid residues 880–1010 in the coiled-coil region of myosin VIIa (Hasson et al., 1995). In a healthy cell the tail of myosin VI is bound to other proteins such as disabled-2, GIPC, and SAP97 (reviewed in Buss et al., 2004). Similarly, the coiled-coil region of the myosin VIIa tail allows the monomer form of the protein to form homodimers (Weil et al., 1997). Having other molecules bound to the antigenic sites would block the antibodies from binding to them, attenuating the overall signal. In a damaged cell, however, the intracellular activity of myosin VI could be downregulated or the myosin VIIa homodimers released, thereby exposing the antigenic sites and increasing the fluorescent labeling. The observed changes in myosin expression coincide with the blebbing and ejection of apoptotic cells and are most likely not triggered by an influx of sodium ion into the cell (Shi et al., 2005). Another consideration arises in the effects of increasing pH of the apoptotic cell on the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophores used. FITC increases its fluorescence in apoptotic leukocytes (Wilkins et al., 2006). The degradation of the nucleus, composed of nucleic acids, may result in a net increase in the alkalinity of apoptotic hair cells, thereby causing in the observed labeling increase.

Changes in the activity of myosin VI could also explain its redistribution into the stereocilia of blebbing hair cells. Myosin VI has been implicated in binding the cell membrane to the bases of the stereocilia (Hirose et al., 2004), but it is not normally found in the bundle. If myosin VI’s attachments to the base of the stereocilia bundle were released, then cytoplasmic myosin VI could diffuse into the previously isolated stereocilia compartment of the hair cell. The release of myosin VI may be mediated by the destruction of f-actin during apoptosis (Hu et al., 2002). Myosin VI is also crucial for the structural integrity of the apical membrane surface of hair cells in zebrafish (Seiler et al., 2004). The apical membrane surface is the sight of the first blebbing activity between 36 and 40 hours (Mangiardi et al., 2004). If myosin VI were no longer bound to the cytoskeleton, it would allow the apical membrane surface to distort its normal shape and thereby bleb out of the sensory epithelium.

Both myosin VI and VIIa form complexes with adhesion proteins like E-cadherin (Geisprecht and Montell, 2002), protocadherin 15, cadherin 23 (reviewed in Wolfrum, 2003), and vezatin (Kussel-Andermann et al., 2000; Sousa et al., 2004), anchoring them to the actin cytoskeleton. The changes in the intensity of the staining indicate that these adhesion complexes may be released when the hair cells are ejected from the sensory epithelium. The release of N-cadherin (similar to E-cadherin) adhesion complexes between supporting cells and hair cells has been implicated in sensory epithelial cell proliferation (Warchol et al., 2002), potentially linking unconventional myosins to hair cell regeneration.

BrdU uptake

BrdU is incorporated into replicating DNA during the S-phase of the cell cycle. Since cochlear supporting cells are normally quiescent in mature birds, the number of BrdU-labeled cells will correspond to the mitotic activity in the regenerating cochlea. Stone and Rubel (2000) reported BrdU-labeled nuclei, mitotic figures, and paired nuclei in the chick basilar papilla 6 hours after BrdU injection. The current study employed a 4-hour BrdU exposure, and demonstrated strong labeling of supporting cells in S-phase. Only about 3% of BrdU-labeled nuclei were paired (data not shown), providing a representative count of supporting cells entering S-phase. The shorter BrdU exposure may explain why there were fewer BrdU-labeled nuclei than previously reported (Bhave et al., 1995).

Our findings are similar to those of previous studies showing that the peak of S-phase activity occurs 3 days following gentamicin treatment (Bhave et al., 1995; Stone and Rubel, 2000), which is 1 day later than the peak in S-phase activity caused by noise damage (Hashino and Salvi, 1993; Stone and Cotanche 1994). The data contained in a study of continuous delivery of BrdU to the inner ear via an osmotic pump demonstrated the greatest increase in BrdU labeling between 4 and 5 days after gentamicin (Roberson et al., 2004). It is unclear whether the shift in BrdU uptake data is a reflection of how the nuclear counts were performed or if it was because they used a continuous BrdU delivery.

Nonmitotic regeneration of hair cells

The current study establishes myosin VI as an early hair cell differentiation marker. Previously, β-III tubulin had been used as an early hair cell differentiation marker and is first expressed 84–86 hours after gentamicin treatment (Stone and Rubel, 2000; this study). Colabeling of myosin VI and β-III tubulin at 84 hours definitively identifies these cells as immature hair cells and not neural processes, which are also strongly labeled by β-III tubulin in the sensory epithelium. Other hair cell markers, such as cProx1 and calmodulin, are not expressed until 5 days after gentamicin treatment (Stone et al., 2004). Myosin VIIa did not label the β-III tubulin-positive cells until 90 hours after gentamicin. The 12-hour delay between myosin VI and myosin VIIa expression is consistent with previous observations of hair cell differentiation during embryonic development. During the development of murine cochlear hair cells, myosin VI is expressed at embryonic day 13.5 (Montcouquiol and Kelley, 2003), whereas myosin VIIa appears in cochlear hair cells 12–24 hours later (Matthew Kelley, pers. commun.). This parallel indicates that there may be a similar mechanism shared between embryonic hair cell development and regeneration of hair cells following aminoglycoside damage.

The first regenerating hair cells arise ~8–12 hours after the beginning of the DNA synthesis phase of regeneration, but were not BrdU-labeled. When put into the context of the 36-hour period between BrdU injection to the first BrdU/myosin VI colabeled cells, it seems unlikely that the earliest myosin VI cells could arise from a mitotic origin. Therefore, the current data support the previous demonstration that the earliest hair cells that appear during regeneration arise through the direct transdifferentiation of supporting cells, as proposed by Roberson et al. (2004). However, the majority of the regenerating hair cells still appear to arise via supporting cell mitosis.

Mitotic regeneration of hair cells

Following a single injection of BrdU, colabeling of hair cell-specific myosin VI with BrdU was not observed until 108 hours after gentamicin, 36 hours after the BrdU injection. The gap of ~30 hours between the first regenerating hair cells and the first BrdU colabeled hair cells indicates that the earliest cells could not have arisen by mitotic means. To do so, they would have to have entered S-phase at 42 hours, before the peak of apoptosis in the chick ear and well before the first cells take up BrdU at 60 hours. Roberson et al. (2004) reported that, following constant BrdU delivery by osmotic pump, the first new regenerated hair cells that appeared between days 4 and 6 did not label with BrdU and proposed that they arose by direct transdifferentiation. Our data demonstrate that there are two very different timelines for regenerating hair cells by mitotic and nonmitotic means.

Consistent with previous data, myosin VIIa was expressed in BrdU colabeled cells 5 days after gentamicin (Roberson et al., 2004), indicating that the overall timeline of mitotic hair cell regeneration is consistent. The relative timing of myosin expression was the same in newly differentiating hair cells produced mitotically and nonmitotically. This implies that once the hair cell precursors receive the signal to differentiate, they do so along the same pathway and may even be triggered to differentiate by the same signal. Furthermore, only BrdU labeling and time distinguish the mechanism of hair cell regeneration. This is consistent with development where supporting cells and hair cells share a common clonal origin (Fekete et al., 1998; Lang and Fekete, 2001). Mitotic division following hair cell loss may be a way of repopulating the depleted cellular density of the damaged sensory epithelium and the distinction between hair cells produced by direct transdifferentiation versus mitotic regeneration may be arbitrary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicole Allen, Nicole Faulk, Jessica Levine, and Caitlin Terry for technical assistance, Dr. Christina Kaiser for critically reading the article, and Dr. Matthew Kelley for insight into myosin expression during hair cell development.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant number: DC01689; Grant sponsor: Deafness Research Foundation; Grant sponsor: Samuel P. Rosenthal and Dossberg Foundation; Grant sponsor: Sarah Fuller Fund (all to D.A.C.); Grant sponsor: National Organization for Hearing Research Foundation; Grant sponsor: the American Hearing Research Foundation; Grant sponsor: NIH Individual NRSA Fellowship; Grant number: EY14790 (all to J.I.M.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Adato A, Michel V, Kikkawa Y, Reiners J, Alagramam KN, Weil D, Yonekawa H, Wolfrum U, El-Amraoui A, Petit C. Interaction in the network Usher syndrome type 1 proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;14:347–356. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler HJ, Raphael Y. New hair cells arise from supporting cell conversion in acoustically damaged chick inner ear. Neurosci Lett. 1996;210:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird RA, Torres MA, Schuff NA. Hair cell regeneration in the bullfrog vestibular otolith organs following aminoglycoside toxicity. Hear Res. 1993;65:164–174. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90211-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird RA, Steyger PS, Schuff NR. Mitotic and non-mitotic hair cell regeneration in the bullfrog vestibular otolith organs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;781:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb15693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham-McDonogh O, Rubel EW. Hair cell regeneration: winging our way towards a sound future. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham-McDonogh O, Osterle EC, Stone JS, Hume CR, Huynh HM, Hayashi T. Expression of Prox1 during mouse cochlear development. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:172–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.20944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave SA, Stone JS, Rubel EW, Coltrera MD. Cell cycle progression in gentamicin damaged avian cochlea. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4618–4628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04618.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss F, Luzio JP, Kendrick-Jones J. Myosin VI, an actin motor for membrane traffic and cell migration. Traffic. 2002;3:851–858. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss F, Spudich G, Kendrick-Jones J. Myosin VI: cellular functions and motor properties. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:649–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.094243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, Rubel EW. Hair cell death in the avian basilar papilla: characterization of the in vitro model and caspase activation. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4:91–105. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, Rubel EW. Mechanisms of hair cell death and protection. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:343–348. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000186799.45377.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey D. Sensory transduction in the ear. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1–3. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotanche DA. Regeneration of hair cell stereociliary bundles in the chick cochlea following severe acoustic trauma. Hear Res. 1987;30:181–195. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotanche DA. Structural recovery from sound damage and aminoglycoside damage in the avian cochlea. Audiol Neurootol. 1999;4:271–285. doi: 10.1159/000013852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotanche DA, Lee KH, Stone JS, Picard DA. Hair cell regeneration in the bird cochlea following noise damage or ototoxic drug damage. Anat Embryol. 1993;189:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00193125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Cruz EM, Pollard TD. Kinetics and thermodynamics of phalloidin binding to actin filaments from three divergent species. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14054–14061. doi: 10.1021/bi961047t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LJ, Williamson K, Mangiardi DA, Cotanche DA. Changes in two unconventional myosins during gentamicin induced hair cell death and regeneration in the inner ear. Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2004;27:807. [Google Scholar]

- Fekete DM, Muthukumar S, Karagogeos D. Hair cells and supporting cells share a common progenitor in the avian ear. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7811–7821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07811.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Schacht J. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol Neurootol. 2000;5:3–22. doi: 10.1159/000013861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisprecht ER, Montell DJ. Myosin VI is required for E-cadherin mediated border cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:616–620. doi: 10.1038/ncb830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillessen T, Tokai F, Breiter K. Specific labeling of neurons and glia in mixed cerebrocortical cultures. Neural Notes. 2000;18:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hackney CM, Furness DN. Mechanotransduction in vertebrate hair cells: structure and function of the stereociliary bundle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C1–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashino E, Salvi RJ. Changing spatial patterns of DNA replication in the noise damaged chick cochlea. J Cell Sci. 1993;105:23–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson T, Mooseker MS. Porcine myosin-VI: characterization of a new mammalian unconventional myosin. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:425–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson T, Heintzelman MB, Santos-Sacchi J, Corey DP, Mooseker MS. Expression in cochlea and retina of myosin VIIa, the gene product defective in Usher 1B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9815–9819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Westrum LE, Stone JS, Zirpel L, Rubel EW. Dynamic studies of ototoxicity in mature avian auditory epithelium. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;884:389–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Westrum LE, Cunningham DE, Rubel EW. Electron microscopy of degenerative changes in the chick basilar papilla after gentamicin exposure. J Comp Neurol. 2004;470:164–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BH, Henderson D, Nicotera TM. F-actin cleavage in apoptotic outer hair cells in chinchilla cochleas exposed to intense noise. Hear Res. 2002;172:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husmann KR, Morgan AS, Girod DA, Durham D. Round window administration of gentamicin: a new method for the study of ototoxicity of cochlear hair cells. Hear Res. 1998;125:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas JD, Cotanche DA, Rubel EW. Avian cochlear hair cell regeneration: stereological analyses of damage and recovery from a single high dose of gentamicin. Hear Res. 1995;92:17–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussel-Andermann P, El-Amroui A, Safienddine S, Nouaille S, Perfettini I, Lecuit M, Cossart P, Wolfrum U, Petit C. Vezatin, a novel transmembrane protein, bridges myosin VIIa to the cadherin-catenins complex. EMBO J. 2000;19:6020–6029. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Fekete DM. Lineage analysis in the chicken inner ear shows differences in clonal dispersion for epithelial, neuronal and mesenchymal cells. Dev Biol. 2001;234:120–137. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiardi DA, McLaughlin-Williamson K, May KE, Messana EP, Mountain DC, Cotanche DA. Progression of hair cell ejection and molecular markers of apoptosis in the avian cochlea following gentamicin treatment. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475:1–18. doi: 10.1002/cne.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui JI, Cotanche DA. Sensory hair cell death and regeneration: two halves of the same equation. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:418–425. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000136873.56878.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui JI, Oesterle EC, Stone JS, Rubel EW. Characterization of damage and regeneration in cultured avian utricles. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2000;1:46–63. doi: 10.1007/s101620010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JC, Stone NL, Erhardt J, Pittman RN. Apoptotic membrane blebbing is regulated by myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:627–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molea D, Stone JS, Rubel EW. Class III beta-tubulin expression in sensory and nonsensory regions of the developing avian inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 1999;406:183–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montcouquiol M, Kelley MW. Planar and vertical signals control cellular differentiation and patterning in the mammalian cochlea. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9469–9479. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09469.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberholtzer JC, Schneider ME, Summers MC, Saunders JC, Matschinsky FM. The developmental appearance of a major basilar papilla specific protein in the chick. Hear Res. 1986;23:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redowicz MJ. Myosins and pathology: genetics and biology. Acta Biochim Pol. 2002;49:789–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GP, Forge A, Kross CJ, Fleming J, Brown SDM, Steel KP. Myosin VIIa is required for aminoglycoside accumulation in cochlear cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9506–9519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09506.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GP, Forge A, Kros CJ, Marcotti W, Becker D, Williams DS, Thorpe J, Fleming J, Brown SDM, Steel KP. A missense mutation in myosin VIIa prevents aminoglycoside accumulation in early postnatal cochlear hair cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;884:110–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson DW, Kreig CS, Rubel EW. Light microscopic evidence that direct transdifferentiation gives rise to new hair cells in regenerating avian auditory epithelium. Auditory Neurosci. 1996;2:195–205. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson DW, Alosi JA, Messana EP, Cotanche DA. Effect of violation of the labyrinth on the sensory epithelium in the chick cochlea. Hear Res. 2000;141:155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson DW, Alosi JA, Cotanche DA. Direct transdifferentiation gives rise to the earliest new hair cells in regenerating avian auditory system. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:461–471. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J, Raff MC, Cramer LP. An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler C, Ben-David O, Sidi S, Hendrich O, Eusch A, Burnside B, Avraham KB, Nicolson T. Myosin VI is required for structural integrity of the apical surface of sensory hair cells in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2004;272:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self T, Sobe T, Coperland NG, Jenkins NA, Avraham KB, Steel KP. Role of myosin VI in the differentiation of cochlear hair cells. Dev Biol. 1999;214:331–341. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Gillespie PG, Nuttall AL. Na+ influx triggers bleb formation in inner hair cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:1332–1341. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00522.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa S, Cabanes D, El-Amraoui A, Petit C, Lecuit M, Cossart P. Unconventional myosin VIIa and vezatin, two protiens crucial for Listeria entry into epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2121–2130. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittaels K, Van den Haute C, Van Dorpe J, Geerts H, Mercken M, Bruynseels K, Lasrado R, Vandezande K, Laenen U, Boon T, Van Lint J, Vandenheede J, Moechars D, Loos R, Van Leuven F. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 phosphorylates protein tau and rescues the axonopathy in the central nervous system of human four-repeat tau transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41340–41349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JS, Cotanche DA. Identification of the timing of S phase and the patterns of cell proliferation during hair cell regeneration in the chick cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 1994;341:50–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JS, Rubel EW. Temporal, spatial, and morphologic features of hair cell regeneration in the avian basilar papilla. J Comp Neurol. 2000;417:1–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000131)417:1<1::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JS, Shang JL, Tomarev S. cProx1 immunoreactivity distinguishes progenitor cells and predicts hair cell fate during avian hair cell regeneration. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:597–614. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME. Cell density and N-cadherin interactions regulate cell proliferation in the sensory epithelia of the inner ear. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2607–2616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02607.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil D, Kussel P, Blanchard S, Levy G, Leci-Acobas F, Drira M, Ayadi H, Petit C. The autosomal recessive isolated deafness, DFNB2, and the Usher 1B syndrome are allelic defects of the myosin VIIa gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:191–193. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins RC, Bellier PV, Kutzner BC, McNamee JP. Increased FITC fluorescence on LPS stimulated neutrophils cultured in whole blood. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrum U. The cellular function of the usher gene product myosin VIIa is specified by its ligands. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;533:133–142. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0067-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]