ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To assess family physicians’ interactions with mental health professionals (MHPs), their satisfaction with the delivery of mental health care in primary health care settings, and their perceptions of areas for improvement.

DESIGN

Mailed survey.

SETTING

Province of Saskatchewan.

PARTICIPANTS

All FPs in Saskatchewan (N = 816) were invited to participate in the study; 31 were later determined to be ineligible because they were specialist physicians, were no longer practising regularly, or could not be located.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Family physicians’ self-reported satisfaction with and interest in mental health care; perceived strengths and areas for improvement in the quality of mental health care delivery in primary health care settings.

RESULTS

The response rate was 48%, with 375 FPs completing the survey. More than half of the responding FPs (56%) reported seeing 11 or more patients with mental health problems per week. Although 83% of responding FPs were interested or very interested in identifying or treating mental health problems, fewer than half (46%) reported being satisfied with the mental health care they were able to deliver. Family physician satisfaction was significantly higher among those with on-site MHPs (P < .05) and those who saw fewer patients with mental health problems per week (P < .01). The most common mode of interaction that FPs reported having with MHPs was through written correspondence; somewhat less common were telephone and face-to-face interactions. The most common strength FPs identified in their provision of mental health care was having access to psychiatrists, community mental health nurses, and other MHPs. The most common area for improvement in primary mental health care also fell under the category of access. Specifically, FPs felt access to psychiatrists needed to be improved.

CONCLUSION

Mental health problems are very common in primary care. Most FPs are very interested in the detection and treatment of mental health problems. Despite this high level of interest, however, FPs are generally dissatisfied with the quality of mental health care they are able to provide. Access to MHPs was cited as a critical element in improving the delivery of mental health services in primary care.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Examiner les interactions des médecins de famille (MF) avec des professionnels de la santé mentale (PSM), leur satisfaction en regard de la dispensation des soins de santé mentale en contexte de soins primaires et leur opinion sur les points qui nécessitent une amélioration.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête postale.

CONTEXTE

La Saskatchewan.

PARTICIPANTS

Les 816 MF de la Saskatchewan ont été invités à participer à l’étude; 31 ont été ensuite écartés parce qu’ils étaient des spécialistes, avaient cessé de pratiquer ou n’avaient pas pu être localisés.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

Déclarations des médecins concernant leur satisfaction et leur intérêt pour les soins de santé mentale; leur perception des points positifs et de ceux à améliorer dans la qualité des soins de santé mentale dispensés en contexte de soins primaires.

RÉSULTATS

Le taux de réponse était de 48%, 375 MF ayant répondu à l’enquête. Plus de la moitié des répondants (58%) déclaraient voir au moins 11 patients souffrant de problèmes de santé mentale par semaine. Quoique 83% des répondants se soient montrés intéressés ou très intéressés à identifier ou à traiter les problèmes de santé mentale, moins de la moitié (46%) se disaient satisfaits des soins de santé mentale qu’ils pouvaient dispenser. Le niveau de satisfaction était significativement plus élevé chez les MF disposant de PSM localement (P < 0,05) et chez ceux qui voyaient moins de patients avec des problèmes de santé mentale par semaine (P < 0,01). Le mode de communication avec les PSM le plus souvent utilisé par les médecins était la correspondance écrite; les communications téléphoniques et les rencontres individuelles étaient un peu plus rarement utilisées. Le facteur positif le plus souvent cité par les MF à propos des soins de santé mentale qu’ils dispensaient était l’accès à des psychiatres, infirmiers communautaires en santé mentale et autres PSM. Selon les MF, le domaine nécessitant le plus d’améliorations en santé mentale de première ligne était l’accès, plus particulièrement l’accès aux psychiatres.

CONCLUSION

Les problèmes de santé mentale sont très fréquents en médecine de première ligne. La plupart des MF sont très intéressés à identifier et à traiter ces problèmes. Malgré leur haut niveau d’intérêt, les MF se montrent généralement peu satisfaits de la qualité des soins de santé mentale qu’ils peuvent dispenser. L’accès à des PSM a été mentionné comme un élément clé dans l’amélioration des soins de santé mentale dispensés en médecine de première ligne.

Family physicians play vital roles, both directly and indirectly, in mental health care. As many as 40% of patients seeking help for mental health problems are seen only by FPs,1,2 and FPs are often the first point of contact for people dealing with mental illness.3–6 However, challenges continue to exist for FPs in detection and treatment of those problems.7–9 Family physicians often report difficulties accessing mental health specialists for consultations or referrals.6,10,11 These barriers to mental health care are compounded by high demand for FP visits in most practices12–14 and fee-for-service remuneration models that are not conducive to dealing with mental health patients.7,15,16 Recent evidence suggests that those with psychiatric problems might receive better care in special mental health care settings compared with primary care settings.17 However, few such specialty settings exist—primary care remains the main portal to care for most patients with mental health problems.

Shared care models (SCMs) of collaboration have been recommended to improve the recognition and treatment of mental health problems. Several SCMs have been implemented across the country, with varying degrees of success,6,15,18 yet only a few studies have examined the views of FPs regarding shared mental health care. Research has often focused on SCMs or other programs created in artificial environments, where participating FPs and psychiatrists are committed to the concept, and adequate resources and compensation are available. We wanted to examine the status of shared care occurring in primary care settings.

Given the chronic shortage of psychiatrists in Saskatchewan and the availability and importance of other mental health professionals (MHPs),16 for the purpose of our study we defined shared care as collaboration between FPs and a wide variety of MHPs, including psychiatrists, psychologists, community mental health nurses, and social workers. We conducted a provincial survey of all FPs to determine the type and frequency of their interactions with MHPs, their satisfaction with the delivery of mental health care in primary care settings, and their perceptions of areas for improvement.

METHODS

Sampling and procedure

All FPs in Saskatchewan (N = 816) were mailed a self-administered survey entitled “Survey of mental health care in the primary care setting.” As per the Dillman Total Design Method,19 nonrespondents were sent 2 subsequent copies of the survey. In order to encourage completion of the survey, a letter of invitation from the researchers with an endorsement from the Saskatchewan Medical Association (SMA) was included, along with a form to request study results and a prestamped response envelope addressed to the SMA. Nonrespondents received separate updated cover letters with each of the 2 re-sent surveys to encourage participation. In addition, each survey was assigned an arbitrary identification number, randomly generated by the SMA. This allowed the SMA to collect and track completed surveys, ensuring that physicians who responded did not receive the survey again; it also allowed them to determine the response rate. Specialty physicians and those physicians no longer practising were excluded from the sample.

Questionnaire development

We completed an in-depth review of the literature on shared mental health care and made several visits to FP practices in order to understand, first-hand, the type of shared care that was being practised in the province. The survey was designed to assess the extent of integrated processes, or shared care, practised in primary care settings in Saskatchewan (whether MHPs work in the primary care setting with FPs, whether FPs and MHPs meet regularly to discuss common clients, etc). The 4-page, 53-item questionnaire eventually developed was based on several of the principles and communication strategies described in the 1997 position paper, Shared Mental Health Care in Canada,1 and was further informed by SCMs described in the literature and by Dillman’s19 approach to survey development. The survey was pilot-tested for clarity, ease of reading, and content validity. Pilot tests were done with 9 FPs and psychiatrists with expertise in clinical practice, shared mental health care, and survey methodology. (The survey is available from the authors upon request.)

Questions were grouped into 4 sections. Section 1 focused on demographic and practice-related data (eg, size of community or number of mental health patients seen per week). Section 2 addressed the quantity and quality of physician interaction with various MHPs, (eg, location of MHPs relative to FPs; communication with MHPs), based on a 5-point Likert scale. This section also addressed the frequency of 14 shared care activities. Section 3 examined physicians’ satisfaction with and interest in mental health care, using a 5-point scale. Section 4 included 2 open-ended questions about the strengths and areas for improvement in FP-provided mental health care: “What existing elements or characteristics in your primary mental health service delivery do you think are contributing to good patient care?” and “What do you think could lead to improvements in the mental health care you are able to provide to your patients?”

Data analysis

Questionnaires were coded and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 9.0. The Cochrane-Armitage test was conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software, version 8.2. For the 2 open-ended survey questions, a researcher and a research assistant developed and revised a coding framework. The research assistant coded all the responses to each question, while another researcher coded only 20% of the responses to each question. Interrater agreement was 84% for the first open-ended question and 80% for the second.

Ethical considerations

To ensure anonymity, the survey questionnaires were labeled with arbitrary identification numbers and sent (and returned) through the SMA. Returning the survey was considered giving consent to participate in the study. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

Of the 816 physicians who received our survey, 31 were found to be ineligible because they were specialist physicians, were no longer practising regularly, or could not be located. Of the remaining group (N = 785), 375 FPs completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 48%. There were no substantial differences in sex or number of practice years between respondents and nonrespondents.

Mental health problems in Saskatchewan’s primary care setting

Our results showed that 30% of respondents reported seeing between 11 and 20 patients with mental health problems per week, and an additional 26% reported seeing more than 20 mental health patients per week; 27% saw between 6 and 10 of these patients per week, and only 16% saw fewer than 6 mental health patients per week. We discovered a statistically significant trend when we examined community size in relation to the percentage of FPs seeing more than 10 patients with mental health problems per week: 43% for FPs in small rural communities, 52% for those in large rural communities, and 68% for those in the province’s 2 largest cities (P < .001, 2-tailed Cochrane-Armitage test).

Interactions with mental health professionals

Family physicians reported written correspondence to be the most common mode of interaction with MHPs, with 85% of respondents indicating that they communicate in this way at least once a month. Seventy-five percent reported interacting with MHPs by telephone at least once a month, and 53% reported regular monthly (or more frequent) face-to-face interaction with MHPs.

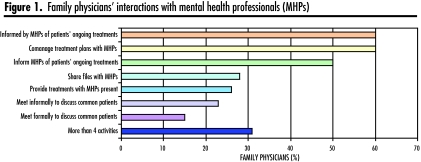

Family physicians were also asked to report the frequency of specific types of mental health activities, most of which required interaction with MHPs. As shown in Figure 1, the most common interactions were FPs being informed of patients’ ongoing treatments and FPs comanaging mental health patients’ treatment plans in collaboration with MHPs; 60% reported that they engaged in these activities. Half of FPs reported that they informed MHPs of patients’ ongoing treatments. The least common interaction was meeting formally or informally with MHPs to discuss common patients.

Figure 1.

Family physicians’ interactions with mental health professionals (MHPs)

Satisfaction with and interest in mental health care delivery

Although 83% of respondents reported that they were interested or very interested in identifying or treating mental health problems, fewer than half (46%) reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the mental health care they were able to deliver. Satisfaction was significantly higher among those with on-site MHPs (P < .05). In addition, the more patients with mental health problems seen per week, the less satisfied FPs were with the mental health care they provided (P < .01).

Strengths and areas for improvement in the provision of mental health care

The first open-ended question asked FPs to identify strengths in the mental health care they provided; the most common strength noted by FPs was having access (in particular, timely access) to psychiatrists, community mental health nurses, and other MHPs. Other commonly identified strengths included the focus on detection, awareness, early intervention, or prevention of mental health problems, and the importance placed on screening for or monitoring mental health symptoms. Providing counseling, having an on-site or visiting MHP, taking the time needed with patients, and staying current with best-practice evidence and training were also common responses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Most common strengths FPs identified in their provision of mental health care: N = 375.

| STRENGTHS | NO. OF RESPONSES |

|---|---|

| Access to MHPs | 55 |

| Focus on detection, awareness, prevention, and screening | 37 |

| Counseling and listening to patients | 31 |

| Having an on-site or visiting MHP | 30 |

| Taking the time needed with patients | 30 |

| Staying current with best-practice evidence and training in primary mental health care | 28 |

| Expertise and support of MHPs | 25 |

MHP—mental health professional.

The second open-ended question asked FPs to identify areas for improvement in the mental health care they provided; in this case, the most common area identified was access to MHPs, especially psychiatrists. Another common response was the need to increase mental health resources, such as human resources, mental health beds, and mental health budgets. Many FPs also expressed dissatisfaction with access to specialists for specific populations, such as child and adolescent psychiatry, emergency cases, or new referrals. Timely and nearby MHP access, communication with MHPs, and educational opportunities for FPs in mental health care were also commonly identified areas for improvement (Table 2).

Table 2.

Most common areas for improvement FPs identified in their provision of mental health care: N = 375.

| AREAS FOR IMPROVEMENT | NO. OF RESPONSES |

|---|---|

| Access to specific MHPs | 121 |

| Enhanced mental health resources | 79 |

| Timely access to specialty mental health care | 57 |

| Access for specific populations or needs | 54 |

| Communication with MHPs (eg, consultation notes) | 47 |

| Nearby access (eg, on-site or visiting MHP) | 33 |

| FP education or information on mental health problems and resources | 32 |

MHP—mental health professional.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that shared mental health care has been examined from FPs’ perspectives—both quantitatively and qualitatively—on a provincial scale. All FPs in Saskatchewan were surveyed, not only to get a sense of the volume of mental health patients in primary care but also to establish a frequency baseline of shared care activities on a provincial level. Saskatchewan’s health care system serves a sparse population across a vast geographic area, which creates many challenges. Given this context, it was especially important to add FP collaboration with various types of MHPs, not just psychiatrists, to the scope of our study.

Our data confirm that FPs are very interested in the detection and treatment of mental health problems, a finding also discovered by Brown et al.13 Despite this high level of interest, however, FPs generally are dissatisfied with the quality of mental health care they are able to provide. Family physicians who reported treating smaller volumes of patients with mental health problems or who had on-site MHPs were more satisfied with the mental health care they were able to provide.

Those FPs who felt they had good access to mental health professionals for their patients recognized this as a strength; those who felt they did not have good access cited this as an area for improvement. Other studies have confirmed that access is a crucial issue.6,13,20 In a province like Saskatchewan, with a small population spread over a large geographic area, access issues can be particularly challenging. Telehealth, electronic health records, Internet tools, and other innovative approaches are increasingly being used to improve access and information sharing. These approaches, however, come with their own implementation challenges,21,22 and further research is needed to distinguish the most appropriate processes or models.23

In future research it might be useful to compare FPs who cited good access to MHPs with those who did not: Were the former more likely to have on-site MHPs or better working relationships with MHPs? Did the latter have lower ratios of MHPs in their respective regions or less knowledge about the mental health services available?

Future efforts to enhance the quality of shared mental health care should involve identification of evidence-based best practices for FP collaboration with, and access to, MHPs. Research and quality improvement efforts should also focus on identifying, implementing, and evaluating the effectiveness of SCMs tailored to community needs.

Finally, we consider the high level of interest in mental health issues to be an additional strength; this bodes well for future implementation of best practices. More than 80% of our survey respondents reported that they were interested or very interested in identifying or treating mental health problems. It is possible, however, that those FPs with greater interest in mental health issues were more likely to respond to the survey than those with less interest. And although this response rate is similar to, if not higher than, those of other recent physician surveys,11,24,25 respondents were not necessarily representative of all FPs in Saskatchewan. The response rate is one of the limitations in our study. Nonetheless, more than 300 FPs responding to our survey reported interest in mental health issues. This suggests that Saskatchewan has a considerable contingent of FPs who are motivated to improve primary mental health care.

Conclusion

Although a high level of interest in mental health problems was reported by FPs, fewer than half of respondents reported being satisfied with the mental health care they are able to deliver to patients. Significantly higher satisfaction rates, however, were reported by FPs with access to on-site MHPs and by those treating smaller numbers of patients with mental health problems. Improved access to MHPs was cited as a critical element in improving primary mental health service delivery.

Acknowledgment

A working group comprising mental health and primary care leaders from across Saskatchewan provided strategic oversight and guidance on this project. Tanya Dunn-Pierce assisted in the design and oversaw the qualitative analysis. Lisa Fedorowich coded data for the 2 open-ended survey questions. We thank the physicians who participated as well as the Saskatchewan Medical Association for their assistance with administering the survey.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Shared care models of collaboration have been recommended to improve the diagnosis and management of mental health problems. This study looks at the status of shared care in Saskatchewan from the perspective of FPs.

Almost half of the FPs in Saskatchewan participated in the study. The results of the study showed that more than 80% saw at least 6 patients per week with mental health problems.

Around 60% of FPs comanaged their patients’ mental health problems with other mental health professionals (MHPs). Most interactions were by telephone or written correspondence. Around one-quarter provided treatment with MHPs present.

Family physician satisfaction was higher with the availability of on-site MHPs.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

On préconise des modèles de soins partagés pour améliorer le diagnostic et le traitement des problèmes de santé mentale. Cette étude veut connaître le point de vue des MF sur la situation des soins partagés en Saskatchewan.

Cette étude regroupait environ la moitié des MF de la Saskatchewan. Les résultats indiquent que plus de 80% d’entre eux voyaient chaque semaine au moins 6 patients avec des problèmes de santé mentale.

Environ 60% des MF traitaient les problèmes de santé mentale en collaboration avec d’autres professionnels de la santé mentale(PSM). La plupart des interactions se faisaient par téléphone ou par correspondance écrite. Environ un quart dispensait le traitement en présence de PSM.

Le niveau de satisfaction des MF était plus élevé lorsque des PSM étaient disponibles localement.

Footnotes

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Ms Clatney participated in the conception and design of the project and in analysis and interpretation of data, and played a lead role in writing and synthesis of this manuscript. Ms MacDonald initiated the research project and played a lead role in design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; and drafting the original study summary report. Dr Shah assisted with revising the article for important intellectual content. All of the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kates N, Craven M, Bishop J, Clinton T, Kraftcheck D, LeClair K, et al. Shared mental health care in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42(8 Suppl):1–12. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesage AD, Goering P, Lin E. Family physicians and the mental health system. Report from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:251–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefebvre J, Lesage A, Cyr M, Toupin J, Fournier L. Factors related to utilization of services for mental health reasons in Montreal, Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(6):291–8. doi: 10.1007/s001270050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin E, Goering P, Offord DR, Campbell D, Boyle MH. The use of mental health services in Ontario: epidemiologic findings. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(9):572–7. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucena RJ, Lesage A, Elie R, Lamontagne Y, Corbière M. Strategies of collaboration between general practitioners and psychiatrists: a survey of practitioners’ opinions and characteristics. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(8):750–8. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockman P, Salach L, Gotlib D, Cord M, Turner T. Shared mental health care. Model for supporting and mentoring family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazeau CM, Rovi S, Yick C, Johnson MS. Collaboration between mental health professionals and family physicians: a survey of New Jersey family physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(1):12–4. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v07n0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg D, Bridges K. Screening for psychiatric illness in general practice: the general practitioner versus the screening questionnaire. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987;37(294):15–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ormel J, Van Den Brink W, Koeter MW, Giel R, Van Der Meer K, Van De Willige G, et al. Recognition, management and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care: a naturalistic follow-up study. Psychol Med. 1990;20(4):909–23. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucena RJ, Lesage A. Family physicians and psychiatrists. Qualitative study of physicians’ views on collaboration. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:923–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Telford R, Hutchinson A, Jones R, Rix S, Howe A. Obstacles to effective treatment of depression: a general practice perspective. Fam Pract. 2002;19(1):45–52. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anfinson TJ, Bona JR. A health services perspective on delivery of psychiatric services in primary care including internal medicine. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(3):597–616. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JB, Lent B, Stirling A, Takhar J, Bishop J. Caring for seriously mentally ill patients. Qualitative study of family physicians’ experiences. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48(5):915–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lester H, Glasby J, Tylee A. Integrated primary mental health care: threat or opportunity in the new NHS? Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(501):285–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craven MA, Bland R. Shared mental health care: a bibliography and overview. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(2 Suppl 1):iS–viiiS. 1S–103S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayabarathan A. Shared mental health care. Bringing family physicians and psychiatrists together. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:341–3 (Eng). 344–6 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrar S, Kates N, Crustolo AM, Nikolaou L. Integrated model for mental health care. Are health care providers satisfied with it? Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2483–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2. Etobicoke, ON: John Wiley & Sons Canada, Inc; 1999. Survey implementation. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kates N. Shared mental health care. The way ahead. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:853–5 (Eng). 859–61 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May C, Harrison R, Finch T, MacFarlane A, Mair F, Wallace P. Understanding the normalization of telemedicine services through qualitative evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(6):596–604. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1145. Epub 2003 Aug 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wootton R. Telemedicine: a cautious welcome. BMJ. 1996;313(7069):1375–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7069.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Currell R, Urquhart C, Wainwright P, Lewis R. Telemedicine versus face to face patient care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD002098. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hillmer M, Krahn M, Hillmer M, Pariser P, Naglie G. Prescribing patterns for Alzheimer disease. Survey of Canadian family physicians. [Accessed 2008 May 2];Can Fam Physician. 2006 52:208–9. e1–6. Available from: www.cfp.ca/cgi/reprint/52/2/208. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Shega JW, Hougham GW, Stocking CB, Cox-Hayley D, Sachs GA. Barriers to limiting the practice of feeding tube placement in advanced dementia. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(6):885–93. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]