ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To describe the role that primary care physicians can play in early recognition of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OOSCCs) and to review the risk factors for OOSCCs, the nature of oral premalignant lesions, and the technique and aids for clinical examination.

QUALITY OF EVIDENCE

MEDLINE and CANCERLIT literature searches were conducted using the following terms: oral cancer and risk factors, pre-malignant oral lesions, clinical evaluation of abnormal oral lesions, and cancer screening. Additional articles were identified from key references within articles. The articles contained level I, II, and III evidence and included controlled trials and systematic reviews.

MAIN MESSAGE

Most OOSCCs are in advanced stages at diagnosis, and treatment does not improve survival rates. Early recognition and diagnosis of OOSCCs might improve patient survival and reduce treatment-related morbidity. Comprehensive head and neck examinations should be part of all medical and dental examinations. The head and neck should be inspected and palpated to evaluate for OOSCCs, particularly in high-risk patients and when symptoms are identified. A neck mass or mouth lesion combined with regional pain might suggest a malignant or premalignant process.

CONCLUSION

Primary care physicians are well suited to providing head and neck examinations, and to screening for the presence of suspicious oral lesions. Referral for biopsy might be indicated, depending on the experience of examining physicians.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Décrire le rôle éventuel du médecin de première ligne dans la détection des épithéliomas malpighiens spinocellulaires oraux et oro-pharyngés (ÉMSOO) et revoir les facteurs de risque associés, la nature des lésions orales précancéreuses, et les techniques et outils facilitant l’examen clinique.

QUALITÉ DES PREUVES

On a répertorié MEDLINE et CANCERLIT à l’aide des rubriques suivantes: oral cancer and risk factors, pre-malignant oral lesions, clinical evaluation of abnormal oral lesions, et oral cancer screening. Des articles additionnels ont été identifiés à partir des références-clés des articles. Les articles présentaient des preuves de niveaux I, II et III, et incluaient des essais randomisés et des revues systématiques.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

La plupart des ÉMSOO sont à un stade avancé au moment du diagnostic, et le traitement n’améliore pas le taux de survie. Une détection et un diagnostic précoces pourraient améliorer la survie et réduire la morbidité associée au traitement. Un examen minutieux de la tête et du cou devrait faire partie de tout examen médical ou dentaire. La tête et le cou devraient être inspectés et palpés à la recherche d’ÉMSOO, notamment chez les patients à risque élevé et en présence de symptômes suspects. Une tuméfaction cervicale ou une lésion orale accompagnée d’une douleur dans la région pourrait suggérer une lésion cancéreuse ou précancéreuse.

CONCLUSION

Le médecin de première ligne est bien placé pour faire l’examen de la tête et du cou, et pour détecter des lésions orales suspectes. Une biopsie pourra être demandée, selon l’expérience du médecin examinateur.

Oral cancer most often refers to squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity (the anatomic region that extends from the lip to the junction of the hard and soft palate superiorly and the vallate papillae of the tongue inferiorly). Oropharyngeal cancers include cancers of the base of the tongue, tonsil, soft palate, and posterior pharyngeal wall. Many oropharyngeal cancers are difficult to see, even when using a tongue blade and light source.

Approximately three-quarters of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OOSCCs) occur among those living in developing countries. In Southeast Asia, OOSCCs account for 40% of all cancers compared with approximately 4% in developed countries.1–3 The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 30 000 new cases of OOSCCs are diagnosed and more than 8000 people die of these cancers in the United States each year.4 In England, the incidence of OOSCCs is 4/100 000 per year across all age groups, but more than 30 cases per 100 000 are diagnosed among those older than 65 years of age.5 More than 90% of OOSCCs occur among patients older than 40 years of age.6

Eighty-one percent of patients with OOSCCs will survive for at least 1 year following diagnosis, while the 5-year relative survival rate for all stages of OOSCCs is approximately 50%.4 Unfortunately, the 5-year survival rate has not changed substantially in the past few decades, despite advances in surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.7,8 For early stage OOSCCs (stage I and II), the 5-year relative survival rate is approximately 80%; whereas for advanced disease (stage III and IV), the 5-year survival rate is less than 25%.4–7 In addition, advanced disease requires more aggressive therapy, employing combined treatments that might result in increased morbidity and cost of care and reduced quality of life. The most logical approach to decreasing morbidity and mortality associated with OOSCCs is to increase detection of suspicious oral premalignant lesions (OPLs) and early detection of OOSCCs. Educating medical and dental professionals and the public about the benefits of preventive screening might help achieve this goal.

The purpose of this article is to review and update the risk factors for OOSCCs, the nature of OPLs, and the technique and aids for clinical examination for reliable clinical screening, and to describe the role that primary care physicians can play in early recognition of OOSCCs.

Quality of evidence

MEDLINE and CANCERLIT literature searches were conducted using the following terms: oral cancer and risk factors, pre-malignant oral lesions, clinical evaluation of abnormal oral lesions, and cancer screening. Additional articles were identified from key references within articles. The articles contained level I, II, and III evidence and included controlled trials and systematic reviews.

Risk factors

Oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas are associated with several well-recognized etiologic risk factors (Table 1). Patients with higher relative risks of developing OOSCCs include those with history of tobacco and alcohol use. More than 70% of patients with OOSCCs report history of tobacco use,9 and about 80% of cases are associated with alcohol or tobacco abuse.10 The risk of OOSCCs increases approximately ninefold among those individuals who have had prior upper aerodigestive tract cancer, compared with the general population.11 Similarly, 20% to 30% of patients with prior history of upper aerodigestive tract cancer develop recurrent disease or second primary cancers.12 The risk of second primary cancers is greater than that attributable to continued tobacco or alcohol use, suggesting that host risk factors further increase the risk of OOSCCs.13

Table 1.

Risk factors for oral premalignant lesions and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

| RISK FACTORS |

|---|

| Age older than 45 y |

| Combined tobacco and alcohol use or abuse |

| Betel nut use |

| Immunosuppression (disease or therapy related) |

| Prior upper aerodigestive tract cancer |

| Sun exposure (lips) |

| Oral human papillomavirus infection |

| HIV infection* |

HIV infection might be associated with increased risk of oral premalignant lesions and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Other reported risk factors for OOSCCs include the following: betel nut chewing; oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection; and chronic immunosuppression following solid organ transplant, hematopoietic cell transplant, and, possibly, HIV infection and AIDS. For example, squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil has the highest prevalence of HPV-16 DNA among the OOSCCs, suggesting increased risk associated with HPV in this location.14 In addition to tobacco and alcohol use, HPV infection, immunodeficiency, and, possibly, genetic changes represent risk factors for OOSCCs among patients with HIV infection.14–18 Individuals older than 45 years of age and African Americans also have higher risks of OOSCCs.3,19

Oral premalignant lesions

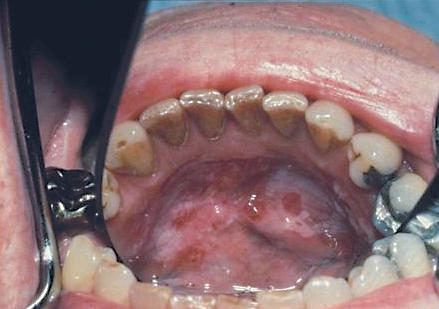

Oral premalignant lesions include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, dysplastic leukoplakia, dysplastic lichenoid lesion, oral submucous fibrosis, and lichen planus (Figures 1–3). The clinical presentations of oral mucosal lesions are presented in Table 2. Oral premalignant lesions have shown a rate of progression of up to 17% within a mean period of 7 years after diagnosis. The highest transformation rate is seen in those lesions with clinically irregular or heterogeneous erythroplakia and dysplastic changes.20,21 Features of OPLs associated with risk of progression to cancer include colour (red, red-white), irregularity (lack of homogeneity), surface texture (granular, verrucous), and location (floor of mouth, ventral or posterolateral border of the tongue).6,22 Ultrastructural changes, including phenotypic change (the presence and severity of dysplasia), DNA instability, and allelic loss (particularly involving chromosome arms 3p, 9p, and 17p, and other molecular markers), affect the risk of developing OOSCCs.22,23

Figure 1.

Irregular leukoplakia (verrucous leukoplakia) with squamous cell carcinoma in the upper right vestibule where a mass can be seen, and dysplasia in the remaining leukoplakia

Figure 3.

Mixed red and white lesion on the floor of the mouth, a high-risk site for cancer

Table 2. Clinical presentations of oral mucosal lesions.

Risk sites include the posterolateral border of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the oropharynx (tonsil, base of tongue).

| CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS |

|---|

| Leukoplakia (white) |

| Erythroplakia (red) |

| Erythroleukoplakia (red and white) |

| Nonhealing ulcers |

| Possible associated pain |

Screening

Population-based screening programs for OPLs and OOSCCs are costly given the low number of lesions in the general population in developed countries. Screening performed by professionals, although more accurate, is more expensive than screening performed by health care auxiliaries.24 Patient participation and settings vary, and economic constraints make it necessary to direct screening efforts toward high-risk individuals.25–29 A simulation model of population screening for OPLs and OOSCCs indicated that approximately 18 000 patients would need to be screened in order to save 1 life.30 This rate is comparable to that for cervical cancer. Therefore, incidental screening has been suggested when patients are seen for other examinations by health care providers. Primary care physicians can provide this type of screening for OPLs and OOSCCs in target individuals.

Definitive guidelines for screening of oral cancer are not well established. The most recent US Preventive Services Task Force report (2004) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for oral cancer among smokers older than 50 and those at low risk.31 The task force found little data on sensitivity and specificity of oral examination for cancer (level II and III evidence). Opportunistic oral cancer screening is recommended by the Canadian Dental Association and the American Dental Association; these organizations emphasize that early detection allows treatment at earlier stages of disease (level III evidence).32,33 The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care reported that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against opportunistic screening and fair evidence to exclude population screening for oral cancer; they did, however, recommend annual examinations for high risk patients (level II evidence).34 Other authors have argued that targeted clinical examination of high-risk individuals might be more effective than mass screening in facilitating early detection of oral cancers.35 Clinical examination appears to provide valid screening, especially when performed by highly trained health care personnel. A recent study in India enrolled nearly 100 000 patients who received oral examinations and compared their outcomes with those of a similarly sized control group not given oral screening examinations (level evidence).36 Among those screened, 205 oral cancers were diagnosed and 77 patients died of oral cancer; in the control population, 158 oral cancers were diagnosed and 87 patients died of oral cancer. Screening examinations were, therefore, associated with reduced mortality among high-risk patients.

Self-examination might be a cost-effective option for OPL and OOSCC screening. A study that examined the feasibility of self-examination of the oral cavity37 reported that of 247 subjects presenting to the participating clinics, 6 (2.4%) had stage I OOSCCs, and only 1 individual was diagnosed with an advanced stage of disease. The detection rate of oral cancer following self-examination compared favourably with examination by trained health care workers.37

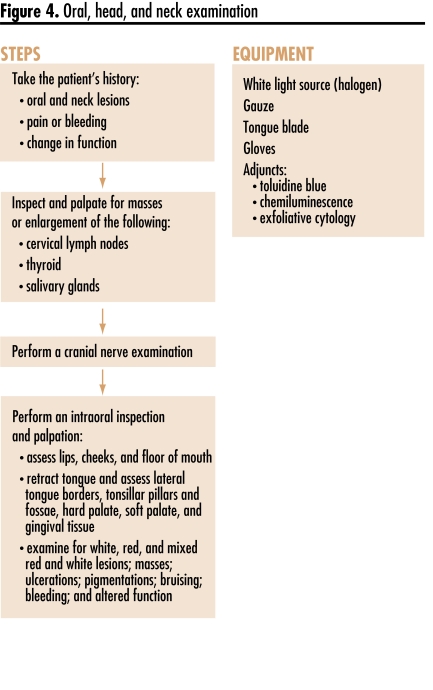

Examination

The examination (Figure 4) must include a comprehensive inspection of the head and neck, with assessment of cervical lymph nodes and cranial nerve function. A neck mass or mouth lesion combined with regional pain might suggest a malignant or premalignant process. A gloved hand and tongue blade or dental mirror can be used to retract the lips and extend the cheeks for visual examination and palpation. Use gauze wrapped around the tongue to assist with retraction and examination of the lateral borders of the tongue. A white light source (halogen) provides the best illumination with colour balance. The highest risk oral sites, including the lateral borders of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, the posterior aspect of the cheek, and the oropharynx, must be evaluated. The first site of spread of OOSCCs beyond the aerodigestive tract is usually to the cervical lymph nodes. Palpation of these nodes must be included as part of every comprehensive head and neck examination. Any lymph node larger than 1 cm should be noted, and the patient should be referred for further evaluation and diagnosis. Some patients with OOSCCs initially present with enlarged lymph nodes without any other signs or symptoms.

Figure 4.

Oral, head, and neck examination

The head and neck examination should include inspection and palpation of the cheeks, parotid glands, and submandibular glands. Asymmetry should be noted and any cutaneous lesions assessed. Intraoral examination is best accomplished with an external light source that enables both hands to be free to retract the cheeks, buccal mucosa, tongue, and lips, allowing full view of all mucosal surfaces. Most hospital rooms do not have appropriate external light sources and require physicians to hold light sources, such as penlights, otoscopes, or ophthalmoscopes, to illuminate the oral cavity. Unfortunately, this prevents a bimanual examination. Examination of the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and larynx is important in any patient with OOSCCs in order to search for second primary tumours and for risk factors and symptoms, including odynophagia, dysphagia, sore throat, or dysphonia. This type of examination requires a mirror and a fiberoptic nasopharyngoscope or laryngoscope. If these are not available, referral to an otolaryngologist might be indicated.

Various aids have been advocated to assist in early detection of OPLs and OOSCCs, but these have not yet been incorporated into guidelines.38 Examination adjuncts have been compared with standard examinations among high-risk or referred populations in several trials providing level II evidence. One randomized controlled trial of toluidine blue provided level I evidence.39 Use of toluidine blue, as a mouth rinse or applied with cotton-tipped applicators to sites of tissue change, has been advocated for identifying lesions, accelerating decision to biopsy, and guiding biopsy site selection.39 Chemiluminescence might make OPLs easier to see; it is used as an adjunct to the Papanicolaou smear to increase detection of dysplastic and neoplastic changes in the cervix.40,41 One study of chemiluminescence for detection of oral lesions found that although white lesions and lesions that were both red and white showed enhanced brightness and sharpness, chemiluminescence did not make red lesions more visible.42 A recent multicentre trial that assessed patients following visual examination with chemiluminescence and toluidine blue applied with swabs found that stain retention reduced the false-positive rate by 55% while maintaining a 100% negative predictive value (level I evidence).43 Additional trials (level II evidence) have assessed tissue autofluorescence in patients known to have cancer and found it to have high sensitivity and specificity,44,45 although this technology has not been applied in noncancer patient evaluations and the role in screening is unknown. Additionally, an exfoliative cytology (brush-type “biopsy”) technique has been developed for accumulating cellular samples of deeper epithelial layers for computerized morphologic and cytologic examination followed by pathologist review.46 Definitive diagnosis, however, requires an open biopsy.

Conclusion

The oral cavity and oropharynx are important areas that should be carefully inspected and palpated, particularly in tobacco and alcohol users, to evaluate for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. A red or white patch or a change in colour, texture, size, contour, mobility, or function of intraoral, perioral, or extraoral tissue should arouse suspicion of the presence of malignant or premalignant lesions in these regions. Comprehensive head and neck examinations should be part of all medical and dental examinations. Primary care physicians are well suited to providing head and neck examinations and to screening for the presence of suspicious lesions. Referral for biopsy and further diagnosis might be indicated, depending on the experience of examining physicians. In the future, examination and screening for oral and oropharyngeal cancers will likely include novel technologies aimed at detecting molecular markers of premalignant and malignant changes.

Levels of evidence

Level I: At least one properly conducted randomized controlled trial, systematic review, or meta-analysis

Level II: Other comparison trials, non-randomized, cohort, case-control, or epidemiologic studies, and preferably more than one study

Level III: Expert opinion or consensus statements

Figure 2.

Asymptomatic red (erythroplakic) lesion involving the soft palate and tonsillar fossa, diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Oral and oropharyngeal cancers account for 4% of cancers in developed countries and up to 40% in developing countries. Risk factors include tobacco and alcohol use.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care does not recommend population screening but suggests annual examinations for those at high risk.

Careful clinical examination is essential for the early detection of oral and oropharyngeal cancers. Examination adjuncts, such as toluidine blue, can be helpful in identifying suspicious lesions.

Definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les cancers oraux et oro-pharyngés représentent 4% des cancers dans les pays développés et jusqu’à 40% dans les pays en voie de développement. Les facteurs de risque incluent le tabagisme et la consommation d’alcool.

Le Groupe d’Étude Canadien sur les Soins de Santé Préventifs ne préconise pas de dépistage universel mais suggère plutôt des examens annuels pour les sujets à risque élevé.

La détection précoce des cancers oraux et oro-pharyngés exige un examen clinique minutieux. Des examens accessoires comme le bleu de toluidine peuvent être utiles pour identifier les lésions.

Le diagnostic définitif requiert une biopsie.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Dr Epstein is a member of the advisory board for and has received research funding from Zila Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about oral cavity and oro-pharyngeal cancer? Tucson, AZ: American Cancer Society; 2006. [Accessed 2007 Jan 18]. Available from: www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_oral_cavity_and_oropharyngeal_cancer_60.asp?sitearea= [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macfarlane GJ, Boyle P, Evstifeeva TV, Robertson C, Scully C. Rising trends of oral cancer mortality among males worldwide: the return of an old public health problem. Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5(3):259–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01830246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Edwards BK, editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1973–1996. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2004. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2004. [Accessed 2007 Jan 18]. Available from: www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/content/STT_1x_Cancer_Facts__Figures_2004.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downer MC. Patterns of disease and treatment and their implications for dental health services research. Community Dent Health. 1993;10(Suppl 2):39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Silverman S., Jr Trends in oral cancer rates in the United States, 1973–1996. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(4):249–56. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman S., Jr Demographics and occurrence of oral and pharyngeal cancers. The outcomes, the trends, the challenge. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(Suppl 1):7S–11S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program public-use data, 1973–1998. Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Greenspan D. Tobacco usage in patients with head and neck carcinomas: a follow-up study on habit changes and second primary oral/oropharyngeal cancers. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;106(1):33–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellsague X, Quintana MJ, Martinez MC, Nieto A, Sánchez MJ, Juan A, et al. The role of type of tobacco and type of alcoholic beverage in oral carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(5):741–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jovanovic A, van der Tol IG, Schulten EA, Kostense PJ, de Vries N, Snow GB, et al. Risk of multiple primary tumors following oral squamous-cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1994;56(3):320–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warnakulasuriya KA, Robinson D, Evans H. Multiple primary tumours following head and neck cancer in southern England during 1961–98. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(8):443–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schantz SP, Spitz MR, Hsu TC. Mutagen sensitivity in patients with head and neck cancers: a biologic marker for risk of multiple primary malignancies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(22):1773–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.22.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross G, Gundlach K, Reichart PA. Virus infections and tumors of the oral mucosae. Symposium of the “Arbeitskreis Oralpathologie und Oralmedizin” and the “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Infektiologie der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft,” Rostock, July 6–7, 2001. Eur J Med Res. 2001;6(10):440–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, Li X, Macabeo-Ong M, Jordan RC. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(6):724–31. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.129760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piattelli A, Rubini C, Fioroni M, Iezzi T. Warty carcinoma of the oral mucosa in an HIV+ patient. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(8):665–7. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anil S, Beena VT, Nair RG. Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva in an HIV-positive patient: a case report. Dent Update. 1996;23(10):424–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flaitz CM, Hicks MJ. Molecular piracy: the viral link to carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol. 1998;34(6):448–53. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hay JL, Ostroff JS, Cruz GD, LeGeros RZ, Kenigsberg H, Franklin DM. Oral cancer risk perception among participants in an oral cancer screening program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(2):155–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53(3):563–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::aid-cncr2820530332>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schepman KP, van der Meij EH, Smeele LE, van der Waal I. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia: a follow-up study of a hospital-based population of 166 patients with oral leukoplakia from The Netherlands. Oral Oncol. 1998;34(4):270–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Cheung KJ, Jr, Lam WL, Cheng X, Poh C, Priddy R, et al. Increased genetic damage in oral leukoplakia from high risk sites: potential impact on staging and clinical management. Cancer. 2001;91(11):2148–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2148::aid-cncr1243>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosin MP, Cheng X, Poh C, Lam WL, Huang Y, Lovas J, et al. Use of allelic loss to predict malignant risk for low-grade oral epithelial dysplasia. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(2):357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jullien JA, Downer MC, Speight PM, Zakrzewska JM. Evaluation of health care workers’ accuracy in recognizing oral cancer and pre-cancer. Int Dent J. 1996;46(4):334–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zakrzewska JM, Martin IC. Oral cancer screening. Br Dent J. 2000;189(3):124–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagao T, Warnakulasuriya S, Ikeda N, Fukano H, Fujiwara K, Miyazaki H. Oral cancer screening as an integral part of general health screening in Tokoname City, Japan. J Med Screen. 2000;7(4):203–8. doi: 10.1136/jms.7.4.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warnakulasuriya S, Pindborg JJ. Reliability of oral precancer screening by primary health care workers in Sri Lanka. Community Dent Health. 1990;7(1):73–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jullien JA, Zakrzewska JM, Downer MC, Speight PM. Attendance and compliance at an oral cancer screening programme in general medical practice. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995;31B(3):202–6. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagao T, Ikeda N, Fukano H, Miyazaki H, Yano M, Warnakulasuriya S. Outcome following a population screening programme for oral cancer and precancer in Japan. Oral Oncol. 2000;36(4):340–6. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Downer MC, Moles DR, Palmer S, Speight PM. A systematic review of test performance in screening for oral cancer and precancer. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(3):264–73. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for oral cancer. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [Accessed 2008 Apr 18]. Available from: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsoral.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canadian Dental Association. Oral cancer. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Dental Association; 2005. [Accessed 2008 May 6]. Available from: www.cda-adc.ca/en/oral_health/complications/diseases/oral_cancer.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Dental Association. Oral cancer. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2007. [Accessed 2008 May 6]. Available from: www.ada.org/public/topics/cancer_oral.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawkins RJ, Wang EE, Leake JL. Preventive health care, 1999 update: prevention of oral cancer mortality. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65(11):617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton LL. The effectiveness of community-based visual screening and utility of adjunctive diagnostic aids in the early detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2003;39(7):708–23. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thomas G, Muwonge R, Thara S, Mathew B, et al. Effect of screening on oral cancer mortality in Kerala, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9475):1927–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathew B, Sankaranarayanan R, Wesley R, Nair MK. Evaluation of mouth self-examination in the control of oral cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(2):397–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mashberg A, Barsa P. Screening for oral and oropharyngeal squamous carcinomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 1984;34(5):262–8. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.34.5.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein JB, Feldman R, Dolor RJ, Porter SR. The utility of tolonium chloride rinse in the diagnosis of recurrent or second primary cancers in patients with prior upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Head Neck. 2003;25(11):911–21. doi: 10.1002/hed.10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu BK, Kuo BI, Yen MS, Twu NF, Lai CR, Chen PJ, et al. Improved early detection of cervical intraepithelial lesions by combination of conventional Pap smear and speculoscopy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24(6):495–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lonky NM, Mann WJ, Massad LS, Mutch DG, Blanco JS, Vasilev SA, et al. Ability of visual tests to predict underlying cervical neoplasia. Colposcopy and speculoscopy. J Reproduct Med. 1995;40(7):530–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Lonky S, Silverman S, Jr, Epstein JD, Bride M. The efficacy of oral lumenoscopy (ViziLite) in visualizing oral mucosal lesions. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26(4):171–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Epstein JB, Silverman S, Jr, Epstein JD, Lonky SA, Bride MA. Analysis of oral lesion biopsies identified and evaluated by visual examination, chemiluminescence and toluidine blue. Oral Oncol. 2007 Nov 8; doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.08.011. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, Durham JS, Williams PM, Priddy RW, et al. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(22):6716–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lane PM, Gilhuly T, Whitehead P, Zeng H, Poh CF, Ng S, et al. Simple device for the direct visualization of oral-cavity tissue fluorescence. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11(2):024006. doi: 10.1117/1.2193157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sciubba JJ. Improving detection of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions. Computer-assisted analysis of the oral brush biopsy. US Collaborative OralCDx Study Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130(10):1445–57. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]