Abstract

NHS costs quickly overtook its budget, resulting in limitations on care. In the third article in his series, Tony Delamothe looks at the difficulties of defining and meeting need

The Government have announced that they intend to establish a comprehensive health service for everybody in this country. They want to ensure that every man and woman and child can rely on getting all the advice and treatment and care which they may need in matters of personal health.1

In this statement of the NHS’s founding principle of comprehensiveness, the crucial word is “need.” The new service was set up to satisfy needs (as defined by doctors and other experts) not demands(as defined by patients). This was in keeping with the circumstances of its birth: the NHS was born into a working class society “strong on collectivism, reconciled to scarcity, and with a firm faith in the rationality of planning.”2

This founding principle encountered two problems: one almost immediately and one as the years passed. The first was money; the second was the transition from a postwar to a consumer society, with widely different values.

Never glad confident morning again

Within months of the launch of the NHS it was clear that the budget had been set too low as people availed themselves of things they needed but had previously gone without—such as spectacles and dental treatment. In 1950—just two years after its inception—a ceiling was imposed on NHS spending, meaning that choices had to be made among competing demands.2 This is the hard choice faced by every government since then: with an ever expanding range of treatments and an ever expanding number of people who could benefit from them, politicians have to choose between raising more money for the NHS (from taxes or personal charges) and not providing certain treatments.

The early casualties of this harsher financial regime were dentistry and eye services. Charges for these were announced in 1951, which prompted the resignation of the minister of health and NHS architect, Anuerin Bevan. The introduction of prescription charges followed in 1952. Thus was abandoned the ideal of a fully comprehensive health service, covering “all necessary forms of health care,” freely available to all.

The NHS has been rationing services (or choosing between priorities) ever since. Use of ophthalmic and dental services has been dampened by shifting ever more of their costs on to consumers. While changes in the provision of these two services have resulted from explicit government decisions, most of the rationing has been covert.

Rudolf Klein contends that doctors took on the government’s dirty work of rationing as the price for preserving their autonomy. “The care that patients received (or did not receive) was presented to them as reflecting their doctors’ assessment of the appropriateness of particular interventions rather than the scarcity of resources.” Ministers and managers were thus able to shelter behind the doctrine of clinical judgment.2

The cost of doctors’ self restraint—if that was the explanation—was high: between 1972 and 1998 Britain spent £220bn (€280bn; $430bn) less on health care than the European Union average.3 Of the varieties of “surreptitious rationing” adopted by Britain to limit access (delaying, deferring, deterring, dissuading, declining), only waiting lists (rationing by delay) gave visibility to the underlying scarcity.4 This accounts for the totemic importance of waiting lists to the government and electorate, not to mention foreign observers of the NHS.

From the early ’90s onwards, however, managers became more open about which procedures they weren’t providing. At various times the blacklist has included extraction of asymptomatic wisdom teeth, operations on varicose veins, in vitro fertilisation, removal of tattoos, cosmetic procedures such as breast enhancement and liposuction, sex change operations, and homoeopathy. By 2007, nearly three quarters of primary care trusts were restricting access to some treatments.5 Restrictions varied around the country, endangering the founding principle of equity.

Who defines comprehensiveness?

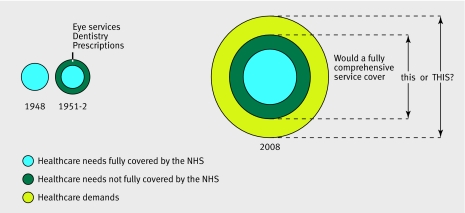

Spending on the NHS has increased from £447m in the first full year of operation to £104bn, a nearly 10-fold increase after adjustment for inflation.6 Yet despite this massive increase in spending, some health care needsremain unmet by the NHS (figure). In addition, there are a range of unmet patient demands, a prime example being cosmetic surgery. Currently, these are satisfied only within the private sector.

Healthcare needs and demands and NHS provision, 1948-2008

This raises the question of who decides what are genuine healthcare needs and what are “merely” demands. And of healthcare needs, which should be met by the NHS. For much of the NHS’s history, it was clear that the decision should rest with “the experts.” One prescription for the future has us sticking within a scientific rationalist model. As the BMA concluded last year:

“In the face of growing technological costs and scientific advances it becomes ever more necessary to assess new treatments to ensure clinical and cost-effective care. We should also review the cost and clinical effectiveness of existing treatments. The NHS should be evidence based. Effectiveness is a core value of the NHS.”7

Yet there is a countervailing current of increasing intensity: consumerism. The first official recognition of the consequences for the NHS of living in a consumer society came with the publication of the government’s white paper, Delivering the NHS Plan (2002).8 9 Patient choice emerged as a the key theme in this paper, which was further amplified in the NHS Improvement Plan (2004). It would “reshape the health services around the needs and aspirations of patients.”10 Lord Darzi’s NHS next stage review envisages a “personalised” NHS, “tailored to the needs and wants of each individual.”11

Taking this new centrality of the consumer to its logical conclusion would see the public rather than a collection of experts defining what “comprehensiveness” means. If so, we’re probably set on a collision course.12 Enough examples exist to show that what patients would like the NHS to provide goes far beyond current provision and would therefore cost more than the current NHS. “If the new model were to prove an escalator for rising fiscal demands,” asks Rudolf Klein, “would the political consensus survive or would there be a revival of the debate about what the scope of a publicly funded health care service should be and how should it be funded?”2

In the meantime, it’s on the battleground of expert defined needs versus patient defined demands that some of the fiercest skirmishes in the NHS are being fought. A classic example is the virulent exchanges over homoeopathy (Doctor: “It doesn’t work, so the NHS shouldn’t provide it”; Patient: “It does for me, so the NHS should”).13

NICE

At the centre of these battles is the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Set up in 1999, its purpose is “to give a strong lead on clinical and cost-effectiveness, drawing up new guidelines and ensuring they reach all parts of the health service.”14 As the key agency deciding what the NHS will and will not pay for, it predictably attracts substantial criticism—over its delays, its threshold for cost effectiveness, the non-transparency of some of its economic models, and its failure to look as critically at current treatments as it does at new ones.

Some parties simply dislike its decisions. NICE’s failure to respond to patients’ demands (usually for an expensive new drug) can bring patient groups out onto the streets and, in extreme cases, to political meddling. Even when NICE has decided in favour of a particular treatment, however, there is no guarantee that it will be provided. Budgetary constraints at the local level mean that funding all NICE guidance, as well as maintaining existing services, is impossible.15

There is increasing discussion around treatments, which apparently meet a genuine need, but which aren’t (yet) available from the NHS. Should patients even be told about them, if NICE has not yet adjudicated on their cost effectiveness? After all, the treatments “might” work, and denying such information to patients may not be in their best interests.16 17

While noting that the UK lags behind many countries in the adoption of new technologies, Derek Wanless, who reviewed the long term trends affecting the NHS for the treasury, made the point that being quick is not necessarily a good thing if the new technology is found to be ineffective. “The appropriate response to new technologies is for rapid and consistent diffusion across the health services once robust evidence of their cost effectiveness is available.”18

Bottom line

In the end it comes down to money and the hard political choice between raising more money for the NHS and deciding not to provide certain treatments. How much more would the NHS cost if “comprehensive” was defined as meeting patients’ demands? The BMA contends that there is “probably a limitless potential” for spending money (on patients’ demands), which include:

Treatments marginally better than cheaper alternatives

Unproved treatments

New, very expensive treatments

Psychological and lifestyle support

Treatments that aim for perfection of human beings and their lifestyle rather than the achievement of a normal level of functioning.

But, without providing supporting figures, the BMA concludes that “the cost-effective evidence-based provision of treatment that will genuinely meet a need to treat an illness that impairs life expectancy or normal levels of social functioning is probably not a bottomless pit.”7

Because discussions about comprehensiveness inevitably end up as discussions about costs, I will return to the topic next week, when I examine the NHS’s founding principles of central funding and services free at the point of delivery.

Competing interests: None declared.

This is the third of six articles marking 60 years of the NHS

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Department of Health for Scotland. A National Health Service (Cmd 6502). London: HMSO, 1944

- 2.Klein R. The new politics of the NHS: from creation to reinvention Abingdon: Radcliffe, 2006

- 3.Wanless D. Securing our future health: taking a long-term view (interim report) London: HM Treasury, 2001

- 4.Leatherman S, Sunderland K. Quality of care in the NHS of England. BMJ 2004;328:E288-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seddon N. Quite like heaven? Options for the NHS in a consumer age London, Civitas: 2007

- 6.Hawe E. OHE compendium of health statistics 2008 19 ed. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 2008

- 7.BMA. A rational way forward for the NHS in England: a discussion paper outlining an alternative approach to health reform London, BMA: 2007

- 8.Secretary of State for Health. Delivering the NHS Plan London:Department of Health, 2002. (Cmnd 5503.)

- 9.Klein R. The new model NHS: performance, perceptions and expectations. Br Med Bull 2007;81-2:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Secretary of State for Health. NHS improvement plan: putting people at the heart of public services London, Department of Health, 2004. (Cmnd 6268.)

- 11.Department of Health. Our NHS, our future. NHS next stage reviewLondon: DoH, 2007

- 12.Klein R. The goals of health policy: church or garage. In Harrison A, ed. Health Care UK 1992/93 London: King’s Fund Institute, 1993

- 13.Colquhoun D. What to do about CAM? BMJ 2007;335:736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health. The new NHS: modern, dependable London: DoH, 1997. (Cmnd 3807.)

- 15.Leatherman S, Sutherland K. The quest for quality: refining the NHS reforms. London: Nuffield Trust, 2008

- 16.Jefford M, Savulescu J, Thomson J, Schofield P, Mileshkin L, Agalianos E, et al. Medical paternalism and expensive unsubsidised drugs. BMJ 2005;331:1075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcus R, Firth J. Should you tell patients about beneficial treatments that they cannot have? BMJ 2007;334:826-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wanless D. Securing our future health: taking a long-term view (final report). London: HM Treasury, 2002.