Abstract

If bone strength was the only requirement of skeleton, it could be achieved with bulk, but bone must also be light. During growth, bone modelling and remodelling optimize strength, by depositing bone where it is needed, and minimize mass, by removing it from where it is not. The population variance in bone traits is established before puberty and the position of an individual's bone size and mass tracks in the percentile of origin. Larger cross-sections have a comparably larger marrow cavity, which results in a lower volumetric BMD (vBMD), thereby avoiding bulk. Excavation of a marrow cavity thus minimizes mass and shifts the cortex radially, increasing rigidity. Smaller cross-sections are assembled by excavating a smaller marrow cavity leaving a relatively thicker cortex producing a higher vBMD, avoiding the fragility of slenderness. Variation in cellular activity around the periosteal and endocortical envelopes fashions the diverse shapes of adjacent cross-sections. Advancing age is associated with a decline in periosteal bone formation, a decline in the volume of bone formed by each basic multicellular unit (BMU), continued resorption by each BMU, and high remodelling after menopause. Bone loss in young adulthood has modest structural and biomechanical consequences because the negative BMU balance is driven by reduced bone formation, remodelling is slow and periosteal apposition continues shifting the thinned cortex radially. But after the menopause, increased remodelling, worsening negative BMU balance and a decline in periosteal apposition accelerate cortical thinning and porosity, trabecular thinning and loss of connectivity. Interstitial bone, unexposed to surface remodelling becomes more densely mineralized, has few osteocytes and greater collagen cross-linking, and accumulates microdamage. These changes produce the material and structural abnormalities responsible for bone fragility.

Keywords: Ageing, Bone, Growth, Modelling, Remodelling, Fragility, Strength

Introduction

Propulsion against gravity requires rigidity for leverage, so long bones must be stiff. Impact loading imparts energy that cannot be destroyed so bone must also be flexible to absorb energy by changing shape [1]. The elastic properties of bone allow it to absorb energy by deforming reversibly when loaded [2, 3]. If the load imposed exceeds the bone's ability to deform elastically, irreversible plastic deformation is accompanied by permanent shape change with accumulation of microcracks that allow energy release [1]. The ability to develop microdamage is defence against the alternative—complete fracture—but microcracking compromises strength as it accumulates [4]. If both elastic and plastic zones of deformation are exceeded, structural failure—fracture—occurs. Bone must also be light to allow mobility.

Bone achieves the paradoxical properties of stiffness yet flexibility and strength yet lightness through its material composition and its structural design. Type 1 collagen is tough and distensible, but lacks resistance to bending so is stiffened by creating a composite of collagen plus mineral. Greater mineral content produces greater material stiffness, but the ability to deform and so absorb and store energy decreases [1]. Ossicles in the ear are over 80% mineral, sacrificing the ability to deform in favour of stiffness. The antlers of deer are less densely mineralized to facilitate deformation. Greater energy-absorbing capacity of antlers is favoured over stiffness, which is not needed as they are not load-bearing [5].

Growth and the attainment of peak bone strength and minimal mass

During growth, bone material is fashioned into three-dimensional masterpieces of biomechanical engineering by bone modelling, the formation of bone by osteoblasts without prior bone resorption. This process is vigorous during growth and changes bone size and shape. During remodelling, bone is refashioned first by resorption by osteoclasts, which remove bone, and then osteoblasts deposit bone in the same location. These cells form the basic multicellular unit (BMU), which reconstructs bone in distinct locations on the three (endocortical, intracortical and trabecular) components of its inner (endosteal) envelope and to a much lesser extent on the periosteal (outer) envelope [6, 7].

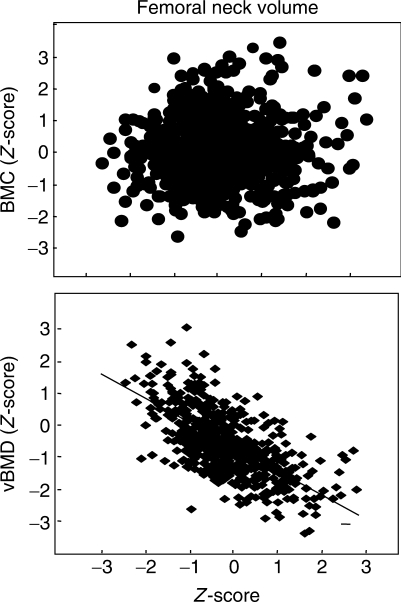

Achieving strength by modifying mass distribution rather than mass

If bone had only to be strong it could achieve this with bulk, but bone must also be light to facilitate mobility. Longer tubular bones need more mass to construct their greater length than shorter bones, but wider and narrower cross-sections do not necessarily differ in the amount of material needed to construct them [8]. Wider and narrower bone cross-sections are assembled using a similar amount of material, so larger cross-sections are assembled with less material relative to their size, producing a lower apparent volumetric BMD (vBMD) avoiding bulk. Smaller cross-sections are assembled with more material relative to their size, producing a higher vBMD and avoiding the fragility of slenderness (Fig. 1). Wider tubular bones are assembled with a thinner cortex (producing the same bone area because the thinner ‘ribbon’ of cortex is distributed around a larger perimeter).

Fig. 1.

There is no association between the BMC Z-score and the volume of a femoral neck (including marrow volume), so larger cross-sections are assembled with relatively less mass and have a lower apparent vBMD. E. Seeman with permission.

The diversity in bone size, shape and mass distribution is the result of differing degrees of focal modelling around the periosteal perimeter and remodelling at the corresponding point on the endocortical surface during growth. Bone strength is optimized using the minimum net amount of bone needed. For example, total cross-sectional area (CSA) of the femoral neck is greatest adjacent to the shaft of the femur and smaller nearer the femoral head, but the amount of bone in each cross-section is no different (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Femoral neck size and shape varies along its length. Similar amounts of bone are used to assemble each cross-section, despite varying total CSA, shape and proportions of cortical and trabecular bone. Adjacent to the femoral shaft, the femoral neck is elliptical and the bone is mainly cortical with varying cortical thickness (Ct.Th) at each point around the perimeter. At the mid-femoral neck and adjacent to the femoral head where the femoral shaft (FS) is more circular, there is more trabecular bone and reciprocally less cortical bone, which is similar in thickness around the perimeters. Adapted from Zebaze et al. [8] with permission of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Adjacent to the femoral shaft, the femoral neck cross-section is elliptical with a long axis in the supero-inferior direction. Greater periosteal apposition superiorly and inferiorly than medio-laterally produces the elliptical shape. Greater periosteal apposition and perhaps less endocortical resorption inferiorly produces a thicker cortex than superiorly [8]. The bone in the cross-section at the junction of the femoral neck with the femoral shaft is largely cortical. Moving proximally, femoral neck shape becomes more circular, reflecting similar degrees of periosteal apposition around the perimeter, and the bone mass is distributed progressively more as trabecular and less as cortical bone, while cortical thickness is similar around the perimeter.

Early establishment of differences in bone size, shape and mass

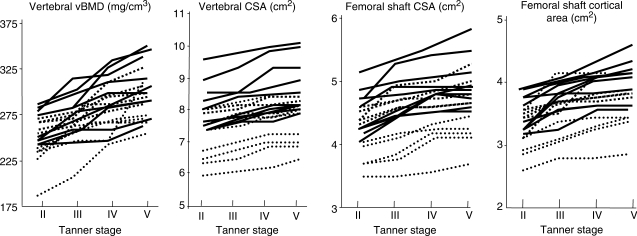

Differences in bone size are established early in life, before puberty and perhaps even in utero. In a 3-yr prospective study of growth in 40 boys and girls, Loro et al. [9] report that the variance at Tanner Stage 2 (pre-puberty), in vertebral CSA and vBMD, femoral shaft CSA and cortical area, was no less than at Tanner Stage 5 (maturity); 60–90% of the variance at maturity was accounted for by the variance present before puberty. Thus, the magnitude of trait variances is established before puberty [9]. The ranking of individual values at Tanner Stage 2 was unchanged during 3 yrs in girls (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Variances in vertebral vBMD and CSA, femoral shaft total CSA and cortical area are established before puberty in girls. Individual values track retaining their percentile of origin during 3 yrs. Adapted from Loro et al. [9] with permission from the Endocrine Society.

These traits were tracked, and an individual with a large vertebral or femoral shaft cross-section, or higher vertebral vBMD or femoral cortical area, before puberty had these traits at maturity.

The deposition of the same amount of bone on the periosteal surface of an already larger cross-section confers more bending resistance than deposition of the same amount of bone on a smaller cross-section, because resistance to bending is proportional to the fourth power of the distance from the neutral axis [10]. In this way, larger cross-sections are assembled with less mass (relative to their size) avoiding bulk, while smaller cross-sections are assembled with more mass (relative to their size), offsetting the fragility of slenderness.

Sexual dimorphism in bone structure rather than mass

The vertebral body is wider in males than in females [11]. Trabecular number per unit area is constant during growth; therefore, individuals with a low trabecular number in young adulthood are likely to have lower trabecular numbers in childhood [12]. The age-related increase in trabecular density is the result of increased thickness of existing trabeculae. Before puberty, there is no difference in trabecular density in boys and girls of either Caucasian or African American origin [13]. At puberty, trabecular density increases, but within a race there is no sex difference in trabecular density.

Growth does not build a ‘denser’ vertebral body in males than females, it builds a bigger vertebral body in males. Strength of the vertebral body is greater in young males than females because of size differences. Within a sex, African Americans have a higher iliac crest trabecular density than whites due to a greater increase in trabecular thickness [14].

As tubular bones increase in length by endochondral apposition, periosteal apposition widens the bone while concurrent endocortical resorption excavates the marrow cavity. As periosteal apposition is greater than endocortical resorption, the cortex thickens. In females, earlier completion of longitudinal growth with epiphyseal fusion and earlier inhibition of periosteal apposition produces a smaller bone. Cortical thickness is similar in males and females because endocortical apposition in females contributes to final cortical thickness [15]. Cortical thickness is similar by race and sex; what differs is the position of the cortex relative to the long axis of the long bone [16]. Racial differences in trabecular vBMD are also reported, but the morphological basis for these differences is yet to be defined [17].

Variance in bone mass at completion of growth is an order of magnitude greater than variance in rates of bone loss during ageing (1 s.d. = 10% vs 1%, respectively), so bone size, architecture and mass attained during growth determine the relevance of bone loss during advancing age. For example, in children with larger tibial cross-sections, the advantage of avoiding bulk by assembling the larger bone with a relatively thinner cortex may be a disadvantage when age-related bone loss occurs. Women with hip fractures and their daughters have larger femoral neck diameters and reduced vBMD [18].

Adulthood and the emergence of bone fragility

The purpose of modelling and remodelling during adulthood is to maintain bone strength by removing damaged bone. Bone, like roads, buildings and bridges, develops fatigue damage during repeated loading, but only bone has a mechanism enabling it to detect the location and magnitude of the damage, to remove it, replace it with new bone and so to restore the bone's material composition, micro- and macro-architecture [19, 20]. Resorption is not necessarily bad. The resorptive phase of the remodelling cycle removes damaged bone and is essential to bone health. The formation phase of the remodelling cycle restores the bone's structure.

Microcracks damage the canalicular system causing osteocyte apoptosis [21]. Osteocytic death from many causes, such as corticosteroid therapy or oestrogen deficiency, is associated with loss of bone strength and so may be a form of damage itself [22, 23]. Osteocyte death provides the topographical information needed to identify the location and extent of damage, initiate osteoclastogenesis and provide an appropriately sized work force of osteoclasts for targeted remodelling. Apoptosis precedes osteoclastogenesis [24, 25]. Death of the osteocyte-like cell line MLO-Y4, induced by scratching, results in the formation of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive cells along the scratching path. Osteocyte apoptosis occurs within 3 days of immobilization and is followed by osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption [26].

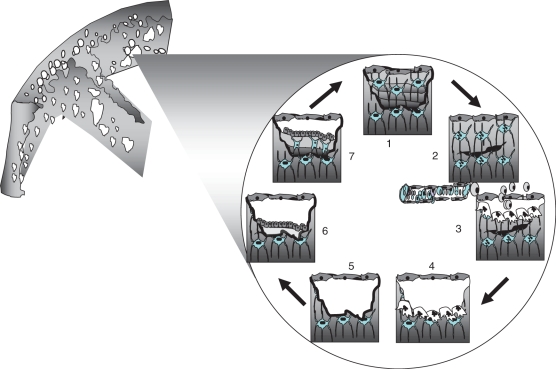

Damage may be signalled via the osteocytic network to flattened bone lining cells, which digest unmineralized osteoid creating a cavity beneath which becomes a bone remodelling compartment (BRC). Osteoclast precursors may be delivered from the marrow via the circulation for both cortical osteonal remodelling and trabecular hemiosteonal remodelling [27]. Osteoblast precursors may arise from local marrow stromals, from the circulation or from the canopy of the BRC. Whatever the mechanism, bone formation follows resorption partly or completely refilling the excavation site. Most osteoblasts die, others become lining cells, while others are entombed in osteoid leading to ‘rewiring’ of the osteocytic canalicular communicating system for subsequent mechanotransduction, damage detection and repair [28] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

(1) Osteocytes are connected by processes to each other and to lining cells on the endosteal surface. (2) Damage to osteocytic processes by a microcrack produces osteocyte apoptosis. The distribution of apoptotic osteocytes provides information needed to target osteoclasts to the damage. (3) Osteoclast precursors may be delivered from the marrow via the circulation. (4) Osteoclasts resorb damage and bone. (5) The reversal phase and formation of a cement line. (6) Osteoblasts deposit osteoid. (7) Some osteoblasts are entombed in osteoid and differentiate into osteocytes reconstructing the osteocytic canalicular network. E. Seeman, with permission.

Abnormalities in bone remodelling

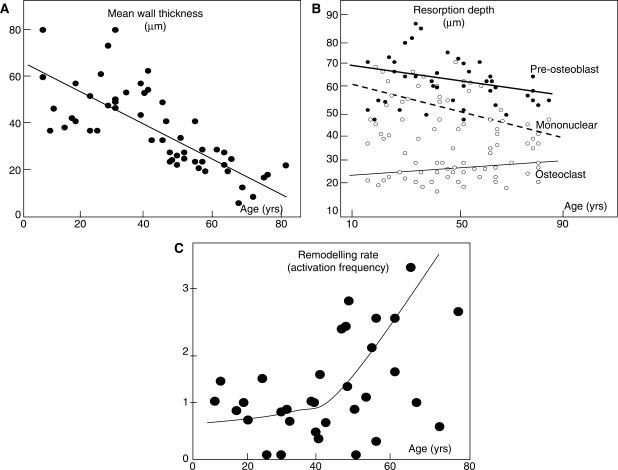

Four age-related changes in bone modelling and remodelling compromise bone's material properties and structural design [29]. (i) A reduction in bone formation at the tissue level. Periosteal apposition slows precipitously after completion of longitudinal growth and continues in adulthood modestly during the next 60 yrs [30–32]. (ii) A reduction in bone formation at the cellular level within each BMU [33, 34]. (iii) Continued resorption in the BMU. The volume of bone resorbed in each BMU does not increase, but decreases or remains unchanged [23, 35, 36]. (iv) An increase in the rate of bone remodelling after the menopause accompanied by worsening of the negative bone balance in each BMU as the volume of bone resorbed increases and the volume of bone formed decreases in the many more BMUs now remodelling bone [23] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Bone loss is the result of: (A) a reduction in the volume of bone formed in each basic metabolic unit—a reduction in mean wall thickness with age. Adapted from Lips et al. [33] with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media. (B) A fall or little change in the volume of bone resorbed in each basic metabolic unit reflected in little age-related change in erosion depth as defined by the distance from the bone surface to the bottom of the erosion pit as lined by pre-osteoblasts, mononuclear cells or osteoclast surfaces (Adapted from Ericksen [35]) with permission from the Endocrine Society. (C) Increased remodelling rate (activation frequency). Courtesy, J. Compston.

At some stage in young adulthood, the volume of bone formed in the formation phase of a remodelling cycle is less than the volume of bone resorbed in the resorptive phase of that cycle producing a net negative BMU balance, bone loss, structural decay and bone fragility. Bone mass decreases in young adulthood due to the decline in bone formation [37–39]. About 40% of the trabecular bone lost across life is lost before the age of 50 yrs in women and men, but cortical loss is minimal before the age of 50 yrs. The consequences are likely to be less than bone loss later because remodelling rate is slow, bone loss proceeds by reduced bone formation rather than increased bone resorption in the BMU, bone loss proceeds by trabecular thinning rather than by loss of connectivity, producing less loss of strength [40]. Periosteal apposition partly offsets endocortical bone loss and shifts the cortices radially [32].

At the menopause, the steady state is perturbed by an increase in the birth rate of new BMUs on bone's endosteal envelope. The many BMUs remove bone while the fewer BMUs created before the menopause complete remodelling by depositing bone. This perturbation produces accelerated bone loss and a rapid decline in BMD. This is a partly reversible loss of bone mass and bone mineral is produced by the normal delay in onset and slower progression of the formation phase of the remodelling cycle [41]. The temporary deficit in bone mass and mineral has three components, the excavation site, the osteoid that lacks mineral and bone that has undergone primary but not secondary mineralization, the slow enlargement of crystals of calcium hydroxyapatite-like mineral whose completion takes months to years [42].

Bone loss slows in the 3–5 yrs after the menopause because the steady state is restored at a new higher remodelling rate. Now the large numbers of BMUs created producing resorption of bone are matched by completion of bone formation of their remodelling cycle and by the large numbers of BMUs created in the perimenopause. Bone loss continues at a faster rate than before the menopause, but at a slower rate than immediately after, because BMU balance is perhaps more negative than before the menopause. Now there are many more sites being created and completed, but the negative BMU balance produces a permanent deficit in bone mass and mineral mass driven by the high remodelling rate.

Structural changes resulting from abnormalities in remodelling

Remodelling occurs on bone surfaces. As trabecular bone has more surface per unit bone volume than cortical bone, accelerated bone remodelling initially produces more trabecular than cortical bone loss. Complete loss of trabeculae reduces the surface available for remodelling, but remodelling on endocortical and intracortical surfaces increases the surface available for remodelling in cortical bone; cortical bone is trabecularized. Cortical thinning occurs and increased porosity results in an increase in the surface/volume ratio in cortical bone. The total bone surface available for resorption does not change (increasing in cortical bone, decreasing in trabecular bone) or increases (in regions of cortical bone only), so that late in life bone loss is more cortical than trabecular in origin. The continued remodelling at a similar intensity with its negative BMU balance on the same amount or more surface removes the same amount of bone from an ever decreasing amount of bone accelerating bone loss and structural decay.

Rapid remodelling is associated with an increased risk of fracture because more densely mineralized bone is removed and replaced with younger, less densely mineralized bone, reducing stiffness, and excavated resorption sites create stress ‘concentrators’, which predispose to microdamage, and increased remodelling impairs isomerization of collagen [43–45]. Interstitial bone, deep bone, is not exposed to remodelling and becomes more densely mineralized, and more highly cross-linked with advanced glycation products like pentosidine, both of which reduce bone toughness. It is easier for microcracks to travel through a more homogeneously mineralized bone. Interstitial bone, which has fewer osteocytes, accumulates microdamage [46–50]. Cortical thinning and increased porosity reduce resistance to crack propagation. Pores coalesce so that the number of pores in cortical bone decreases, but the total area of porosity increases late in life. The ability of bone to limit crack propagation declines so that bone cannot absorb the energy imparted by a fall and this energy is released in the worst possible way—fracture.

Reduced periosteal apposition

Periosteal apposition during ageing is slow [30]. It is believed to increase as an adaptive response to compensate for the loss of strength produced by endocortical bone loss. In a 7-yr prospective study of over 600 women, Szulc et al. [32] report that endocortical bone loss occurred in pre-menopausal women with concurrent periosteal apposition. Periosteal apposition was less than endocortical resorption so the cortices thinned, but there was no net bone loss because the thinner cortex was distributed around a larger perimeter, conserving total mass, and resistance to bending increased because this same amount of bone was distributed further from the neutral axis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The amount of bone resorbed by endocortical resorption (open bar) increases with age. The amount deposited by periosteal apposition (black bar) decreases. The net effect is a decline in cortical thickness (grey bar). In pre-menopausal women, the thinner cortex is displaced radially increasing section modulus (Z). In perimenopausal women, Z does not decrease despite cortical thinning because periosteal apposition still produces radial displacement. In post-menopausal women, Z decreases because endocortical resorption continues, periosteal apposition declines and little radial displacement occurs. Adapted from Szulc et al. [32] with permission of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Endocortical resorption increased during the perimenopausal period, but periosteal apposition decreased—it did not increase in compensation so the cortices thinned. Nevertheless, bending strength remained unchanged because periosteal apposition was still sufficient to shift the thinning cortex outwards. Bone fragility emerged after the menopause when acceleration in endocortical bone resorption and deceleration in periosteal apposition produce further cortical thinning with little outward displacement of the thinning cortex, so the cortical area now declined, as did resistance to bending.

The periosteal envelope is not only a bone-forming surface [30]. Blizoites et al. [7] report that bone resorption occurs in adult non-human primates. Femurs from 16 intact adult male and female non-human primates showed that periosteal remodelling of the femoral neck in intact animals was slower than in cancellous bone, but more rapid than at the femoral shaft. Gonadectomized females showed an increase in osteoclast number on the periosteal surface compared with intact controls. If these findings are correct, adult skeletal dimensions may decrease in size as age advances.

Fuller Albright suggested over 65 yrs ago that osteoporosis was a disorder of reduced bone formation [51]. During ageing, both increasing endocortical bone resorption and reduced periosteal apposition cause net bone loss, alterations in the distribution of the remaining bone and the emergence of bone fragility. The cellular basis of the vigour of bone formation during growth and progressive decline in vigour during ageing on the periosteal surface and within each BMU is yet to be defined.

Sex differences in trabecular and cortical bone loss

A greater proportion of women than men sustain fragility fractures because (i) men's skeletons are larger than women's, and therefore more resistant to bending; (ii) men do not have a mid-life decline in sex hormones and increase in remodelling rate; (iii) bone loss in most men is the result of a negative BMU balance produced by reduced formation not increased resorption, so trabecular bone loss occurs by thinning rather than loss of connectivity [52]; the loss of strength is less than produced by loss of connectivity [40] even though the amount of trabecular bone loss across age is only slightly greater in women than men [53], or is similar [16, 52, 54–59]; (iv) cortical porosity increases less in men than in women because remodelling rate is lower in men; thus, crack propagation in cortical bone is probably better resisted in men than in women; and (v) periosteal apposition is purported to be greater in men than in women in some [16, 58–59], but not all studies [53].

The absolute risk for fracture in women and men of the same age and BMD is similar [60, 61]. Thus, the lower fracture incidence in men than in women is likely to be the result of lower proportion of elderly men than elderly women with material and structural properties below the level at which the loads on the bone are greater than the bone's net ability to tolerate them. Structural failure occurs less in men because the relationship between load and bone strength is better maintained in men than in women [62].

Heterogeneous material and structural basis of bone fragility in patients with fractures

Patients with fractures do not share the same pathogenesis and structural basis of bone fragility. Patients with vertebral fractures may have high, normal or low remodelling rates [63], while others have a negative BMU balance due to reduced formation, increased resorption, or both, or no negative BMU balance at all [64]. Some patients with vertebral fractures have increased, others reduced, tissue mineral density [65]. Some patients have reduced osteocyte density, while others do not [66]. Whether anti-fracture efficacy can be improved by defining the pathogenesis and structural basis in an individual remains uncertain, but it is worthy of consideration.

Conclusion

Modelling and remodelling are successful during growth, but not ageing. Longevity is accompanied by reduced bone formation on the periosteal envelope and abnormalities in remodelling balance and rate on the endosteal envelope that compromise the material and structural properties of bone. Understanding of why or how bones fail at the material and structural level is essential if we are to provide targeted approaches to drug therapy.

Disclosure statement: E.S. serves on the medical advisory committees of Eli Lilly, GSK, Sanofi-Aventis, Procter and Gamble, MSD, Servier and Novartis, and has been a speaker at national and international meetings sponsored by some of these companies.

References

- 1.Currey JD. Structure and mechanics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2002. Bones; pp. 1–380. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanyon LE, Baggott DG. Mechanical function as an influence on the structure and form of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:436–43. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B4.1018029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner CH. Bone strength: current concepts. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1068:429–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burr DB, Turner CH, Naick P, et al. Does microdamage accumulation affect the mechanical properties of bone? J Biomech. 1998;31:337–45. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currey JD. Mechanical consequences of variation in the mineral content of bone. J Biomech. 1969;2:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(69)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orwoll ES. Toward an expanded understanding of the role of the periosteum in skeletal health. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:949–54. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blizoites M, Sibonga, Turner RT, Orwoll E. Periosteal remodeling at the femoral neck in nonhuman primates. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1060–7. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zebaze RM, Jones A, Knackstedt M, Maalouf G, Seeman E. Construction of the femoral neck during growth determines its strength in old age. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1055–61. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loro ML, Sayre J, Roe TF, Goran MI, Kaufman FR, Gilsanz V. Early identification of children predisposed to low peak bone mass and osteoporosis later in life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3908–18. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruff CB, Hayes WC. Sex differences in age-related remodeling of the femur and tibia. J Orthop Res. 1988;6:886–96. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100060613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeman E. Growth in bone mass and size–are racial and gender differences in bone mineral density more apparent than real? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1414–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parfitt AM, Travers R, Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Structural and cellular changes during bone growth in healthy children. Bone. 2000;27:487–94. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilsanz V, Roe TF, Stefano M, Costen G, Goodman WG. Changes in vertebral bone density in black girls and white girls during childhood and puberty. New Engl J Med. 1991;325:1597–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112053252302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Z-H, Palnitkar S, Rao DS, Nelson D, Parfitt AM. Effect of ethnicity and age or menopause on the structure and geometry of iliac bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1967–75. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garn S. Nutritional perspectives. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1970. The earlier gain and later loss of cortical bone; pp. 3–120. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang XF, Duan Y, Beck T, Seeman E. Varying contributions of growth and ageing to racial and sex differences in femoral neck structure and strength in old age. Bone. 2005;36:978–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan Y, Wang XF, Evans A, Seeman E. Structural and biomechanical basis of racial and sex differences in vertebral fragility in Chinese and Caucasians. Bone. 2005;36:987–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filardi S, Zebaze RM, Duan Y, Edmonds J, Beck T, Seeman E. Femoral neck fragility in women has its structural and biomechanical basis established by periosteal modeling during growth and endocortical remodeling during aging. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:103–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parfitt AM. Skeletal heterogeneity and the purposes of bone remodelling: implications for the understanding of osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J, editors. Osteoporosis. San Diego, CA: Academic; 1996. pp. 315–39. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parfitt AM. Targeted and non-targeted bone remodeling: relationship to basic multicellular unit origination and progression. Bone. 2002;30:5–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazenberg JG, Freeley M, Foran E, Lee TC, Taylor D. Microdamage: a cell transducing mechanism based on ruptured osteocyte processes. J Biomech. 2006;39:2096–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien CA, Jia D, Plotkin LI, et al. Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoblasts and osteocytes to induce their apoptosis and reduce bone formation and strength. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1925–41. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manolagas SC. Choreography from the tomb: an emerging role of dying osteocytes in the purposeful, and perhaps not so purposeful, targeting of bone remodeling. BoneKEy. 2006;3:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark WD, Smith EL, Linn KA, Paul-Murphy JR, Muir P, Cook ME. Osteocyte apoptosis and osteoclast presence in chicken radii 0-4 days following osteotomy. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77:327–36. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurata K, Heino TJ, Higaki H, Väänänen HK. Bone marrow cell differentiation induced by mechanically damaged osteocytes in 3D gel-embedded culture. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:616–25. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguirre JI, Plotkin LI, Stewart SA, et al. Osteocyte apoptosis is induced by weightlessness in mice and precedes osteoclast recruitment and bone loss. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:605–15. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauge EM, Qvesel D, Eriksen EF, Mosekilde I, Melsen F. Cancellous bone remodelling occurs in specialized compartments lined by cells expressing osteoblastic markers. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1575–82. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.9.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han Y, Cowin SC, Schaffler MB, Weinbaum S. Mechanotransduction and strain amplification in osteocyte cell processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16689–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407429101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality—the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. New Eng J Med. 2006;354:2250–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra053077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balena R, Shih M-S, Parfitt A. Bone resorption and formation on the periosteal envelope of the ilium: a histomorphometric study in healthy women. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:1475–82. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seeman E. Periosteal bone formation—a neglected determinant of bone strength. New Eng J Med. 2003;349:320–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szulc P, Seeman E, Duboeuf F, Sornay-Rendu E, Delmas PD. Bone fragility: failure of periosteal apposition to compensate for increased endocortical resorption in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1856–63. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lips P, Courpron P, Meunier PJ. Mean wall thickness of trabecular bone packets in the human iliac crest: changes with age. Calcif Tissue Res. 1978;10:13–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vedi S, Compston JE, Webb A, Tighe JR. Histomorphometric analysis of dynamic parameters of trabecular bone formation in the iliac crest of normal British subjects. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1984;5:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(83)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ericksen EF. Normal and pathological remodeling of human trabecular bone: three dimensional reconstruction of the remodelling sequence in normals and in metabolic disease. Endocr Rev. 1986;4:379–408. doi: 10.1210/edrv-7-4-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Croucher PI, Garrahan NJ, Mellish RWE, Compston JE. Age-related changes in resorption cavity characteristics in human trabecular bone. Osteoporos Int. 1991;1:257–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03187471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riggs BL, Wahner HW, Melton LJ, Richelson LS, Judd HL, Offord KP. Rates of bone loss in the appendicular and axial skeletons of women: evidence of substantial vertebral bone loss before menopause. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1487–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI112462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilsanz V, Gibbens DT, Carlson M, Boechat I, Cann CE, Schulz ES. Peak trabecular bone density: a comparison of adolescent and adult. Calcif Tissue Int. 1987;43:260–2. doi: 10.1007/BF02555144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riggs BL, Melton LJ, Robb R, et al. A population-based assessment of rates of bone loss at multiple skeletal sites: evidence for substantial trabecular bone loss in young women and men. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:205–14. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.071020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van der Linden JC, Homminga J, Verhaar JAN, Weinans H. Mechanical consequences of bone loss in cancellous bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:457–65. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parfitt AM. Morphological basis of bone mineral measurements: transient and steady state effects of treatment in osteoporosis. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1980;4:273–87. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akkus O, Polyakova-Akkus A, Adar F, Schaffler MB. Aging of microstructural compartments in human compact bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1012–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boivin G, Lips P, Ott SM, et al. Contribution of raloxifene and calcium and vitamin D supplementation to the increase of the degree of mineralization of bone in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4199–205. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-022020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez CJ, Gupt A, Keaveny TM. A biomechanical analysis of the effects of resorption cavities on cancellous bone strength. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1248–55. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viguet-Carrin S, Garnero SP, Delmas PD. The role of collagen in bone strength. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:319–36. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailey AJ, Sims TJ, Ebbesen EN, Mansell JP, Thomsen JS, Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in the biochemical properties of human cancellous bone collagen: relationship to bone strength. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65:203–10. doi: 10.1007/s002239900683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banse X, Sims TJ, Bailey AJ. Mechanical properties of adult vertebral cancellous bone: correlation with collagen intermolecular cross-links. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1621–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.9.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Effect of aging on the toughness of human cortical bone: evaluation by R-curves. Bone. 2004;35:1240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu S, Rao DS, Fyhrie DP, Palnitkar S, Parfitt AM. The morphological association between microcracks and osteocyte lacunae in human cortical bone. Bone. 2005;37:10–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeni YN, Brown CU, Wang Z, Norman TL. The influence of bone morphology on fracture toughness of the human femur and tibia. Bone. 1997;21:453–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albright F, Smith PH, Richardson AM. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1941;116:2465–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aaron JE, Makins NB, Sagreiy K. The microanatomy of trabecular bone loss in normal aging men and women. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;215:260–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riggs BL, Melton LJ, III, Robb RA, et al. A population-based study of age and sex differences in bone volumetric density, size, geometry and structure at different skeletal sites. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1945–54. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meunier PJ, Sellami S, Briancon D, Edouard C. Histological heterogeneity of apparently idiopathic osteoporosis. In: Deluca HF, Frost HM, Jee WSS, Johnston CC, Parfitt AM, editors. Osteoporosis. Recent advances in pathogenesis and treatment. Baltimore, MD: UPP; 1990. pp. 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalender WA, Felsenberg D, Louis O, et al. Reference values for trabecular and cortical vertebral bone density in single and dual-energy quantitative computed tomography. Eur J Radiol. 1989;9:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mosekilde L, Mosekilde L. Sex differences in age-related changes in vertebral body size, density and biochemical competence in normal individuals. Bone. 1990;11:67–73. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90052-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seeman E. From density to structure: growing up and growing old on the surfaces of bone. J Bone Min Res. 1997;12:1–13. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seeman E, Duan Y, Fong C, Edmonds J. Fracture site-specific deficits in bone size and volumetric density in men with spine or hip fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:120–7. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duan Y, Wang XF, Evans A, Seeman E. Structural and biomechanical basis of racial and sex differences in vertebral fragility in Chinese and Caucasians. Bone. 2005;36:987–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson B. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:989–95. doi: 10.1007/s001980170006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus Z, et al. Intervention thresholds for osteoporosis in men and women. Bone. 2005;36:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bouxsein ML, Melton LJ, 3rd, Riggs BL, et al. Age- and sex-specific differences in the factor of risk for vertebral fracture: a population-based study using QCT. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1475–82. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown JP, Delmas PD, Arlot M, Meunier PJ. Active bone turnover of the cortico-endosteal envelope in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:954–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-5-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eriksen EF, Hodgson SF, Eastell R, Cedel SL, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Cancellous bone remodeling in type I (postmenopausal) osteoporosis: quantitative assessment of rates of formation, resorption, and bone loss at tissue and cellular levels. J Bone Min Res. 1990;5:311–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ciarelli TE, Fyhrie DP, Parfitt AM. Effects of vertebral bone fragility and bone formation rate on the mineralization levels of cancellous bone from white females. Bone. 2003;32:311–5. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu S, Rao RD, Palnitkar S, Parfitt AM. Reduced iliac cancellous osteocyte density in patients with osteoporotic vertebral fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1657–63. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]