Abstract

Phosphorylations within N- and C-terminal degrons independently control the binding of cyclin E to the SCFFbw7 and thus its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. We have now determined the physiologic significance of cyclin E degradation by this pathway. We describe the construction of a knockin mouse in which both degrons were mutated by threonine to alanine substitutions (cyclin ET74A T393A) and report that ablation of both degrons abolished regulation of cyclin E by Fbw7. The cyclin ET74A T393A mutation disrupted cyclin E periodicity and caused cyclin E to continuously accumulate as cells reentered the cell cycle from quiescence. In vivo, the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation greatly increased cyclin E activity and caused proliferative anomalies. Cyclin ET74A T393A mice exhibited abnormal erythropoiesis characterized by a large expansion of abnormally proliferating progenitors, impaired differentiation, dysplasia, and anemia. This syndrome recapitulates many features of early stage human refractory anemia/myelodysplastic syndrome, including ineffective erythropoiesis. Epithelial cells also proliferated abnormally in cyclin E knockin mice, and the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation delayed mammary gland involution, implicating cyclin E degradation in this anti-mitogenic response. Hyperproliferative mammary epithelia contained increased apoptotic cells, suggesting that apoptosis contributes to tissue homeostasis in the setting of cyclin E deregulation. Overall these data show the critical role of both degrons in regulating cyclin E activity and reveal that complete loss of Fbw7-mediated cyclin E degradation causes spontaneous and cell type-specific proliferative anomalies.

Keywords: Fbw7, cell cycle, cyclin E, phosphodegron

Cyclin E binds to and activates the CDK2 cyclin-dependent kinase subunit, and cyclin E-CDK2 phosphorylates proteins involved in diverse cell cycle processes. Cyclin E also has a CDK-independent function that facilitates the licensing of replication origins as cells exit quiescence (Geng et al. 2007). Although cyclin E normally regulates many aspects of cell division, knockout mice have revealed that most cell cycles proceed normally without cyclin E, which likely results from redundancy among cyclin-CDKs (Geng et al. 2003; Parisi et al. 2003). However, these studies also revealed essential cyclin E functions, including in endoreduplication, reentry of fibroblasts into the cell cycle from quiescence, and oncogenic transformation of fibroblasts in vitro.

Cyclin E-CDK2 activity is regulated during the cell cycle and peaks around the time of S-phase entry (Dulic et al. 1992; Koff et al. 1992). This periodicity results from changes in cyclin E abundance, CDK inhibitor proteins (p21, p27), and CDK2 phosphorylation (for review, see Hwang and Clurman 2005). Cyclin E abundance is regulated by E2F-dependent cyclin E transcription and cyclin E degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome system. Two SCF-type ubiquitin ligases degrade cyclin E: Monomeric cyclin E can be degraded by Cul3-containing complexes (Singer et al. 1999), whereas cyclin E that has bound CDK2 is degraded by the SCFFbw7, which requires cyclin E phosphorylation (Clurman et al. 1996; Won and Reed 1996; Koepp et al. 2001; Moberg et al. 2001; Strohmaier et al. 2001; Welcker et al. 2003; Ye et al. 2004).

Substrate degradation by the SCFFbw7 is stimulated by phosphorylation within motifs called Cdc4-phosphodegrons (CPDs) that bind to Fbw7 (Orlicky et al. 2003). In addition to a central phosphorylated residue, CPDs in Fbw7 substrates also contain a negatively charged residue in the +4 position, and both the central and +4 negative charges contact Fbw7’s WD40 repeats (Nash et al. 2001; Welcker et al. 2003; Ye et al. 2004; Hao et al. 2007). Cyclin E contains two CPDs: a C-terminal degron centered on threonine 380 (T380) and an N-terminal degron centered on threonine 62 (T62) (Clurman et al. 1996; Won and Reed 1996; Koepp et al. 2001; Strohmaier et al. 2001; Welcker et al. 2003; Ye et al. 2004). Both cyclin E degrons are phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) and CDK2 itself, and each can direct Fbw7 binding and cyclin E ubiquitination. However, the T380-containing degron has widely been considered the dominant cyclin E degradation signal, and the physiologic significance of the N-terminal degron has been uncertain. The C-terminal degron, which contains a +4 phosphate, makes more extensive contacts with Fbw7 than the N-terminal degron (Hao et al. 2007), and thus it is thought to be a higher affinity degron (Welcker and Clurman 2008).

Many tumor cells express high levels of cyclin E activity, and abnormal cyclin E activity causes genetic instability and increased tumorigenesis in mice and cultured human cells (Karsunky et al. 1999; Spruck et al. 1999; Minella et al. 2002; Hwang and Clurman 2005; Loeb et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2006; Akli et al. 2007). Multiple mechanisms increase cyclin E activity in tumors. For example, cyclin E is an E2F target gene and its transcription can be positively regulated by Rb pathway mutations (Duronio and O'Farrell 1995; Ohtani et al. 1995; Geng et al. 1996). Cyclin E degradation is also abnormal in tumor cells. This most commonly results from Fbw7-loss, but other oncogenes, such as Ras, may also impair cyclin E degradation in tumor cells (Spruck et al. 2002; Ekholm-Reed et al. 2004; Rajagopalan et al. 2004; Minella et al. 2005). Finally, CDK inhibitor expression is often reduced in cancers (Sherr and Roberts 1999; Tsihlias et al. 1999).

We recently developed a mouse model of cyclin E-associated tumorigenesis in which the C-terminal degron was disrupted by a T393A mutation (murine T393 is the equivalent of human T380) (Loeb et al. 2005). This mutation caused genetic instability and tumorigenesis that was exacerbated by mutations of the p53-p21 pathway. However, ablation of the C-terminal degron did not fully stabilize cyclin E, and we considered the possibility that the N-terminal degron may play a larger role than anticipated in regulating cyclin E stability in vivo.

We have now determined the physiologic role of cyclin E degradation via the Fbw7 pathway by making a double knockin mutation in mice that disrupts both CPDs by combining the T393A mutation with a T74A mutation (murine T74 is equivalent to human T62). Importantly, because Fbw7 degrades several proteins that regulate cell division, growth, and differentiation (e.g., Myc, Notch, Jun), this model isolates cyclin E degradation from these other oncogenic substrates that are also stabilized by Fbw7-loss (Oberg et al. 2001; Nateri et al. 2004; Welcker et al. 2004; Yada et al. 2004; Wei et al. 2005). This approach also allows the role of cyclin E phosphorylation per se to be studied independent of ectopic expression and/or in vitro effects.

The cyclin ET74A T393A mutation dramatically increased cyclin E activity and caused widespread proliferative anomalies that were most severe in hematopoietic cells. Cyclin ET74A T393A mice exhibited abnormal erythropoiesis characterized by expansion of proliferating erythroid progenitors in the spleen and bone marrow, impaired erythroid differentiation, dysplasia, and anemia. This syndrome recapitulates features of human refractory anemia, including ineffective erythropoiesis. Cyclin ET74A T393A epithelial tissues also exhibited abnormal cell proliferation, including impaired mammary gland involution, indicating that cyclin E down-regulation is an important component of the anti-mitogenic response leading to involution. Hyperproliferative cyclin ET74A T393A epithelia also contained increased numbers of apoptotic cells, suggesting that apoptosis plays an important role in maintaining tissue homeostasis in the setting of cyclin E deregulation. Finally, studies in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) indicated that the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation disrupted cyclin E periodicity and caused cyclin E to continuously accumulate during the cell cycle, thus implicating phosphorylation on both cyclin E degrons as a critical determinant of cyclin E oscillation during the cell cycle. Overall, these data indicate that both degrons regulate cyclin E turnover via the Fbw7 pathway in vivo and that complete loss of Fbw7-mediated cyclin E degradation causes tissue-specific proliferative anomalies.

Results

Targeting strategy and development of cyclin ET74A T393A mice

We made a knockin mouse in which both cyclin E degrons were disabled by mutating threonines 74 and 393 to alanine. The targeting construct was similar to that used for targeting T393 (Loeb et al. 2005) but included the T74A mutation, as well as a Ban1 site (Supplemental Fig. 1A,C). After transfection of embryonic stem (ES) cells and selection for G418 resistance, the recombined T74A T393A allele was confirmed by Southern blot, PCR, and genomic DNA sequencing (Supplemental Fig. 1B–D). Cyclin ET74A T393A mice were bred with MORE-Cre mice to eliminate the Neor marker, and Neor deletion was confirmed by PCR and genomic DNA sequencing (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Interbreeding of cyclin ET74A T393A hemizygous mice produced progeny with the expected Mendelian ratios of cyclin E genotypes (Supplemental Fig. 1E). Cyclin ET74A T393A homozygous mice appeared phenotypically normal in size and weight. All subsequent studies comparing cyclin ET74A T393A mice with cyclin ET393A and wild-type animals utilized mice homozygous for the single (T393A) or double (T74A T393A) knockin mutation in the 129Sv genetic background, except as indicated.

Expression and activity of cyclin ET74A T393A in hematopoietic tissues

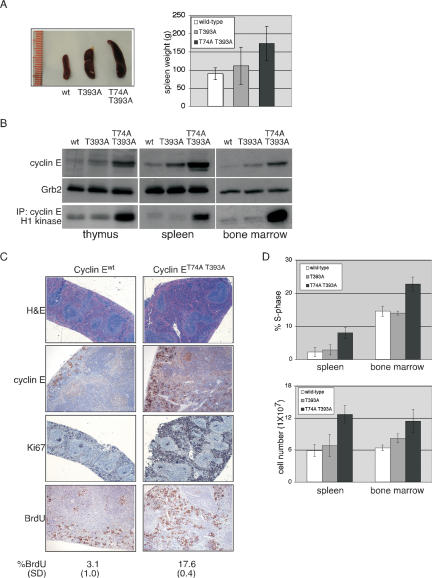

Our previous studies of cyclin ET393A mice revealed that cyclin E expression and activity were below the limits of detection in nonproliferative adult tissues but were easily detectable in tissues with actively dividing cells (Loeb et al. 2005). We thus examined bone marrow, spleen, and thymus tissues in all three genotypes and found greatly elevated cyclin E abundance and activity in cyclin ET74A T393A hematopoietic tissues, as well as splenomegaly (Fig. 1A,B). In contrast, cyclin ET393A mice had normal cyclin E activity in these tissues. Expression of the three cyclin E genotypes was similar in both the 129Sv and C57/BL6 mice backgrounds with one exception: cyclin ET393A activity was elevated in C57/BL6 but not in 129Sv spleens (Loeb et al. 2005; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Analysis of cyclin ET74A T393A-induced hyperproliferation in hematopoietic tissues. (A) Age- and sex-matched animals of the indicated cyclin E genotypes were sacrificed between 20 and 30 wk of age, and spleen lengths and weights were measured. A representative comparison is shown (left panel, ruler increments are in millimeters). Mean weights and standard deviations were calculated from a cohort of 19 mice (right panel). (B) Lysates were prepared from snap-frozen tissues from the indicated genotypes and immunoblotted for cyclin E and Grb2 (loading control) and immunoprecipitated with an anti-cyclin E antibody to assay kinase activity. (C) Representative stainings are shown of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) spleens from cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A mice, using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), anti-cyclin E, anti-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), and anti-Ki67 antibodies. Displayed are 2× (H&E, Ki67) micrographs to show overall splenic architecture and 10× (cyclin E, BrdU) micrographs. Data from quantitative analysis of BrdU incorporation in splenocytes are shown with standard deviations (SD). (D) Whole spleens and bone marrow were obtained from age- and sex-matched animals (six mice per genotype) and single-cell suspensions prepared. (Top panel) S-phase fractions were determined by DAPI incorporation. (Bottom panel) Nucleated cell counts were manually performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Splenomegaly in cyclin ET74A T393A mice resulted from infiltration of the red pulp with highly proliferative cells (as shown by both Ki67 staining and bromodeoxyuridine [BrdU] incorporation) that expressed high levels of cyclin E protein (Fig. 1C). Flow cytometric studies revealed an increased S-phase fraction and hyperplasia in cyclin ET74A T393A spleens and bone marrow (Fig. 1C,D). Thus, the high levels of cyclin ET74A T393A activity caused cellular hyperproliferation in bone marrow and spleen. In contrast, no obvious abnormalities were found in the thymus (data not shown), despite high levels of cyclin ET74A T393A activity, demonstrating tissue-specific responses to abnormal cyclin E activity.

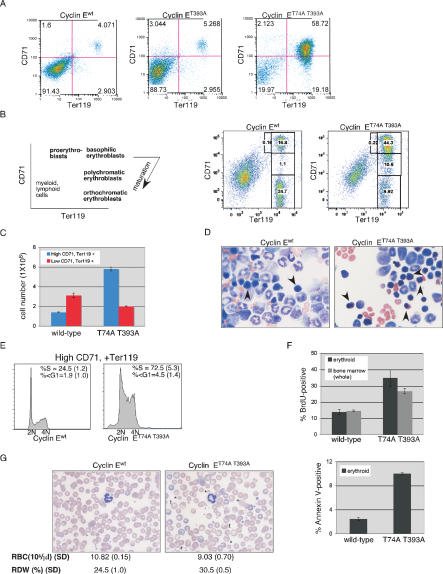

Ineffective erythropoiesis and erythroid dysplasia in cyclin ET74A T393A mice

Bone marrow cells and splenocytes from adult cyclin ET74A T393A mice (but not cyclin ET393A mice) had greatly expanded populations of committed erythroid progenitors, as indicated by positive staining with CD71 (transferrin receptor) and Ter119 (glycophorin A-associated protein) antibodies (Fig. 2A,B; Supplemental Fig. 2A). In contrast, myeloid cells were relatively decreased in cyclin ET74A T393A bone marrow, leading to a reduced myeloid to erythroid ratio (Supplemental Fig. 2A,B). We used CD71 expression to examine erythroid maturation in marrow-derived Ter119+ erythroid progenitors (Socolovsky et al. 2001; Liu et al. 2006; Fig. 2B). Morphologic examination of sorted Ter119+ CD71 subpopulations confirmed that they represented erythroid cells in the indicated stages of differentiation (data not shown). Although the numbers of immature Ter119+ CD71+ erythroid progenitor cells in cyclin ET74A T393A marrow were markedly elevated, the more mature Ter119+ CD71-erythroids were reduced, indicating that cyclin ET74A T393A expression impairs erythroid development and causes ineffective erythropoiesis (Fig. 2B,C). Morphologic analyses revealed increased erythroid progenitors in cyclin ET74A T393A marrow, with frequent mitotic figures and megaloblastic forms containing hemoglobinzed cytoplasm and large, immature nuclei, frequently budded in appearance with extracellular and intracellular nuclear lobes (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. 2C). In contrast, no significant dysplastic changes were present in cyclin ET393A or cyclin Ewt bone marrow. Thus, cyclin ET74A T393A mice contain dysplastic erythroid cells that exhibit cytoplasmic/nuclear asynchrony. Cell cycle analyses of Ter119+ CD71+ cells isolated by cell sorting revealed a greatly increased S-phase fraction in cyclin ET74A T393A cells compared with wild-type Ter119+ CD71+ cells (72.5% vs. 24.5%; Fig. 2E). Finally, we used BrdU incorporation to directly demonstrate increased DNA synthesis in cyclin ET74A T393A total bone marrow and sorted erythroid cells (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Massively expanded erythroid progenitors and abnormal erythroid maturation in cyclin ET74A T393A mice. (A) Splenocytes were harvested from age- and sex-matched adult mice (aged 20–30 wk) and stained with anti-CD71 (transferrin receptor) and anti-Ter119 (glycophorin A-associated protein) to enumerate erythroid progenitor cells. CD71, Ter119 double-positive cells (top right quadrant) were quantified and are expressed as a ratio to total splenocytes. (B) Erythroid maturation was measured in wild-type (wt), cyclin ET393A (T393A), and cyclin ET74A T393A (T74A T393A) bone marrow. (Left panel) Morphologically distinct Ter119-positive populations are identified on the basis of CD71 expression, which was confirmed by sorting and staining for morphologic analysis. (Right panels) CD71, Ter119 profiles of bone marrow cells show abnormal erythroid maturation in cyclin ET74A T393A mice. Numbers within each sector indicate ratio to total bone marrow cells. (C) Absolute numbers of high CD71-, Ter119-positive and low CD71-, Ter119-positive erythroid progenitors are displayed as mean values from two separate experiments (10 mice total). (D) Representative 40× micrographs of Wright-Giemsa stained cytospins from cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A mice, with arrowheads indicating normal-appearing basophilic erythroblasts in the left panel (cyclin Ewt bone marrow) and dysplastic erythroids found in cyclin ET74A T393A bone marrow cytospins (right panel). (E) Cell cycle profiles were obtained from Ter119-positive, high CD71-expression cells isolated from bone marrow. Cells in S-phase and with subgenomic DNA content were measured, and mean values with standard deviations are shown with representative histograms. (F) Quantitative analyses of BrdU incorporation in total bone marrow and Ter119+ cell fractions (top panel) and of anti-Annexin V-staining in Ter119+ cells (bottom panel) are shown. (G) Representative Wright-Giemsa stained peripheral blood smears (40×) from cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A mice showing abnormally small (*), large (+), and target (t) cells. Complete blood counts were obtained from six mice from each genotype, and mean red blood cell counts (RBC) and red blood cell distribution widths (RDW) are shown with standard deviations (SD).

We noted the presence of sorted cyclin ET74A T393A erythroid progenitor cells with subgenomic DNA content, suggesting that increased apoptosis may contribute to the reduced numbers of maturing erythroid cells in these animals (Fig. 2E). We thus used an Annexin V-based staining assay to specifically measure apoptosis and confirmed increased numbers of apoptotic cyclin ET74A T393A erythroid cells (Fig. 2F).

The peripheral blood of cyclin ET74A T393A mice exhibited anemia, anisopoikilocytosis (quantified by red blood cell distribution widths [RDW]), and abnormal red cell morphology (including target cells), findings that are consistent with ineffective erythropoiesis (Fig. 2G). However, these peripheral blood anomalies were less severe than the bone marrow findings, suggesting that homeostatic mechanisms maintain red cell mass in the setting of ineffective erythropoiesis. We also examined whether the T74A T393A mutation affected erythroid enucleation by measuring the enucleation kinetics of cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A mononuclear cells cultured in vitro. We found fewer enucleated cyclin ET74A T393A Ter119+ cells at baseline, and unlike wild-type cells, the cyclin ET74A T393A cells did not accumulate increasing numbers of enucleating erythroid cells (Supplemental Fig. 2D). These data indicate that deregulated cyclin E activity either directly impairs enucleation or that the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation indirectly reduces enucleation in vitro by acting at an upstream step.

We next examined whether abnormal erythropoiesis in cyclin ET74A T393A mice is cell autonomous. We first determined if abnormal erythropoietin production was driving this process and found no significant differences between cyclin ET74A T393A and cyclin Ewt mice (mean erythropoietin values of 294 pg/mL and 233 pg/mL, respectively, with standard deviations between 110 and 130 pg/mL). Next, we performed colony assays using bone marrow cells isolated from adult mice and found that the numbers of BFU-E (which enumerate early erythroid progenitors) derived from cyclin ET74A T393A bone marrow were elevated threefold compared with wild-type animals (Supplemental Fig. 3). These data suggest that cyclin ET74A T393A mice contain increased numbers of early erythroid progenitors, as opposed to alterations in other factors, such as marrow-derived stromal cells. We definitively addressed this issue with bone marrow transplants, in which equal numbers of bone marrow cells (Ly 5.2) obtained from 129Sv wild-type or cyclin ET74A T393A mice were transplanted into irradiated wild-type C57/BL6 recipients. Wild-type competitor cells marked by Ly 5.1 expression were mixed with donor marrow cells prior to transplantation. We sacrificed the recipient animals at 17 wk post-transplant and found that the marrows of cyclin ET74A T393A donor cell recipients had expanded early erythroid progenitors and impaired erythroid maturation similar to that seen in cyclin ET74A T393A mice (Table 1). Additionally, we found increased numbers of Ly 5.2 cyclin ET74A T393A bone marrow-derived cells (relative to Ly 5.1 competitor-derived cells) compared to Ly 5.2 cyclin Ewt recipients, indicating a proliferative advantage for the cyclin ET74A T393A cells. These data show that the ineffective erythropoiesis in the double knockin mice is due to a cell-autonomous defect within marrow-derived hematopoietic cells.

Table 1.

Results of murine bone marrow transplants

At 17 wk following bone marrow transplantation with whole bone marrow obtained from the indicated donor genotypes, recipient mice were sacrificed. Bone marrow cells were obtained for flow cytometry analysis of Ter119 and CD71 expression and peripheral blood collected for chimerism analyses. A total of eight mice were transplanted (four for each donor genotype) and mean ratios calculated with standard deviations (SD) as shown.

In summary, cyclin ET74A T393A mice demonstrated markedly abnormal erythropoiesis. In the marrow this was characterized by a large expansion of immature and abnormally proliferating erythroid progenitors, impaired erythroid differentiation, erythroid dysplasia, and increased apoptosis. These marrow anomalies were accompanied by anemia and defects in red cell size and morphology in the peripheral blood. Overall, these marrow and blood abnormalities share many features with early stage human myelodysplastic syndrome and/or ineffective erythropoiesis.

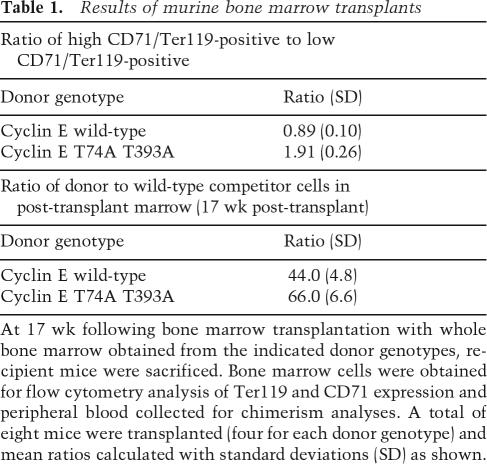

Expression and consequences of cyclin ET74A T393A in epithelial tissues

We detected cyclin E expression by immunocytochemical staining in proliferative epithelia, such as the pregnant mammary gland and the gut, and found that cyclin ET74A T393A expression was much higher than cyclin Ewt in these tissues, whereas cyclin ET393A expression was intermediate (Fig. 3A,B). Abnormal cyclin E expression in these epithelial compartments caused marked hyperproliferation, as measured by both Ki67 staining and BrdU incorporation (Fig. 3C). However, unlike in hematopoietic tissues, the cyclin ET393A mutation was sufficient to cause mammary epithelial hyperproliferation.

Figure 3.

Analysis of cyclin ET74A T393A expression and activity in epithelial tissues. Micrographs at 40× are shown of sections from FFPE colon tissues obtained from age-matched males (A) and mammary glands obtained from females sacrificed during timed breedings (B) and stained with an affinity purified cyclin E antibody. (C) Epithelial cell proliferation was studied in situ in cyclin Ewt, cyclin ET393A, and cyclin ET74A T393A mammary glands by staining tissues for Ki67 proliferation antigen expression and BrdU incorporation. Three age- and gestation time-matched mice per genotype were BrdU pulsed, and positive cells were counted per 40× field (right panel). (Left panels) Micrographs at 20× are shown for cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A mammary glands obtained from pregnant mice at D7.5 pc. At least 40 fields were counted per gland. Bars indicate standard error. (D) Apoptosis was detected in mammary tissues from age- and gestation time-matched mice by staining with anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody, and numbers of positive cells per high power field areshown.

Despite increased cell proliferation, the mammary epithelia of pregnant females and adult colonic epithelia appeared morphologically normal. As we observed in red cells (Fig. 2E,F), one mechanism of tissue homeostasis in these animals may be increased apoptosis, which counters increased cell proliferation. We thus stained mammary epithelia for activated caspase-3 expression (a central mediator of apoptotic cell death) and found increased numbers of caspase-3 positive cells in cyclin ET393A and cyclin ET74A T393A pregnant mammary tissues (Fig. 3D). Therefore, increased apoptosis also appears to counter cyclin E-driven hyperproliferation in mammary epithelial cells.

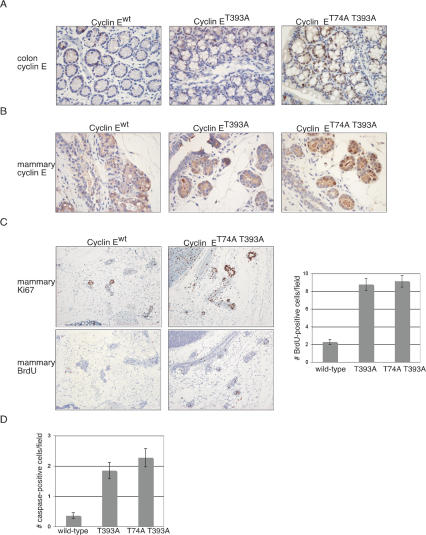

Aberrant mammary involution in cyclin ET74A T393A mammary tissues

Following weaning, the mitogenic signals that drive mammary cell proliferation in nursing females acutely decline, and the mammary gland involutes, during which time secretory cells are eliminated via apoptosis (Watson 2006). We used the involuting mammary gland to study the consequences of deregulated cyclin E expression in the context of anti-mitogenic signaling. We found abnormal persistence of intact acinar structures in involuting mammary glands of cyclin ET74A T393A mice at late time points (16–21 d following weaning; Fig. 4A,B; data not shown). Additionally, whole mount preparations revealed that the size of the terminal mammary duct lobules (comprised of mammary acini) in cyclin ET74A T393A mice remained increased throughout the late involution period (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. 4), and Ki67 staining revealed hyperproliferating mammary epithelial cells in these tissues (Fig. 4D). In contrast to the hyperproliferation seen in mammary tissues of pregnant females, involution in cyclin ET393A mice was indistinguishable from wild-type mice. Thus, the cyclin ET393A mutation is not sufficient to delay involution. We compared the serum concentrations of prolactin and 17-β-estradiol in wild-type and cyclin ET74A T393A mice at multiple time points during the involution process and found that they were not elevated (data not shown). Thus, elevation of these hormones does not account for delayed involution of cyclin ET74A T393A mammary glands, and this phenotype likely occurs in a cell-autonomous manner.

Figure 4.

Delayed mammary involution in cyclin ET74A T393A mice. (A) Mammary acini (indicated by arrowheads) were identified in proximity to ducts (D) and numbers of acinar units were counted per 40× field. Representative 40× micrographs are shown from H&E stained FFPE sections of cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A mammary glands (#4) obtained at involution day 16. Five mice per genotype were compared, with approximately equal-sized litters and matched to involution day number. (B) Average numbers of acinar units per field were calculated from 40 fields per mammary gland. (C) Whole mounts were prepared from involuting #4 mammary glands contralateral to those studied in A, and the size of the terminal duct lobules (TDLs) were compared. The maximal cross-sectional widths of TDLs were measured from 10× images taken of whole mounts using NIH ImageJ software. Thirty to 40 TDLs per mammary gland were measured. (D) Tissue sections from FFPE involuting mammary glands from A were stained for Ki67, and positive-staining epithelial cells per 40× field were counted. Average numbers of Ki67-positive cells per field were calculated. (E) Shown are 40× micrographs from anti-activated caspase 3 stained, involuting mammary glands day 21. (F) Average numbers of caspase-positive cells per field were calculated.

Although involution is slowed in cyclin ET74A T393A females, mammary tissues obtained from parous cyclin ET74A T393A females beyond 1 mo of weaning were morphologically normal (data not shown). Again we found increased activated caspase 3 expression at 21 d following weaning in the cyclin ET74A T393A glands, whereas little activated caspase 3 expression was detectable in cyclin Ewt or cyclin ET393A tissues (Fig. 4E,F). Thus, increased apoptosis may also oppose abnormal cell division in cyclin ET74A T393A mammary glands during involution.

Both cyclin E degrons regulate cyclin E periodicity in mouse embryo fibroblasts

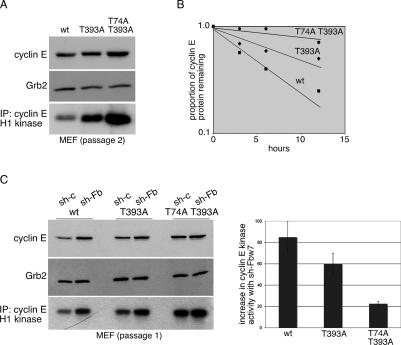

We used mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) to study the effects of disrupting both phosphodegrons on cyclin E expression and activity during the cell cycle. The cyclin ET74A T393A mutation modestly increased cyclin E abundance in asynchronously growing MEFs but resulted in a larger increase in cyclin E kinase activity (Fig. 5A,C). This disparity between cyclin E abundance and activity in cultured MEFs results from the high abundance of p21Cip1 bound to cyclin E-CDK2, which renders a large pool of cyclin E insensitive to Fbw7 (Welcker et al. 2003; Loeb et al. 2005). Nonetheless, we found that cyclin ET74A T393A protein stability in asynchronous MEFs is substantially increased (t1/2 = 22 h) compared to cyclin ET393A and cyclin Ewt (t1/2 = 10 h and 5 h, respectively) (Fig. 5B). Because p21 expression rapidly increases as MEFs are passaged, all of our studies used very early passage MEFs (p1/p2) to minimize these effects. However, the relatively long half-life of endogenous cyclin E in asynchronous cells likely reflects the rate at which cyclin E enters the catalytically active pool as well as its degradation rate.

Figure 5.

Analysis of cyclin ET74A T393A stability and activity in mouse embryo fibroblasts. (A) Western blot analyses of cyclin E abundance in passage 2 MEFs using an affinity purified anti-cyclin E antibody and anti-Grb2 as loading control are shown. Kinase activity using histone H1 as a substrate was measured from cyclin E-immunoprecipitated complexes. (B) Cyclin E protein stability was measured by treating MEFs with cycloheximide and immunoblotting lysates collected at the indicated time points. (C) Freshly isolated MEFs were expanded in culture and transduced with retroviral vectors expressing a short hairpin RNA sequence targeting murine Fbw7 expression (sh-Fb) or a scrambled, control hairpin sequence (sh-c). Following selection, mRNA was harvested from cells to verify Fbw7 knockdown (Supplemental Fig. 5) and cyclin E protein abundance was measured by immunoblotting lysates (left panel). Cyclin E-associated kinase activity was measured and the relative increase (right panel) with Fbw7 knockdown for each set of MEFs determined. Error bars indicate standard deviations calculated from data from duplicate experiments.

To confirm that increased cyclin ET74A T393A stability results from more complete inhibition of Fbw7-mediated degradation (and not by affecting another pathway), we used a previously characterized retroviral small hairpin RNA to inhibit Fbw7 in freshly isolated MEFs (Welcker et al. 2004). Retroviral transductions were equally efficient across all three genotypes and resulted in a fourfold reduction in endogenous Fbw7 mRNA (Supplemental Fig. 5A). Fbw7 knockdown increased cyclin E expression maximally in cyclin Ewt MEFs, less so in cyclin ET393A MEFs, and insignificantly in cyclin ET74A T393A cells, consistent with the idea that cyclin ET393A remains partially susceptible to Fbw7-mediated degradation, whereas cyclin ET74A T393A is resistant (Fig. 5C). The cyclin ET74A T393A allele did not appreciably alter cyclin E mRNA abundance in MEFs (Supplemental Fig. 5B).

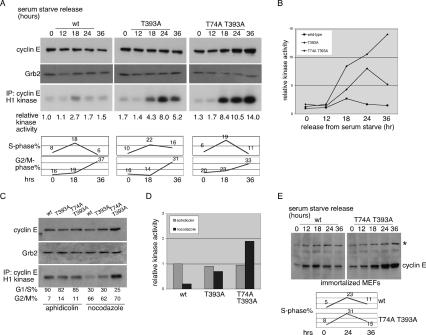

We next used synchronized MEFs to study cyclin E regulation during cell cycle progression. MEFs were made quiescent by serum starvation, and cyclin E abundance and activity were examined throughout a synchronized cell cycle following trypsinization and release into serum. Cyclin E abundance and activity prior to the onset of S-phase entry (18 h after release) were similar across all three MEF genotypes. As cells entered S-phase, the abundance and activity of cyclin ET74A T393A exceeded that of wild-type cyclin E and cyclin ET393A. Strikingly, cyclin ET74A T393A activity and abundance continued to rise as cells entered G2/M, and this was quite different than cyclin ET393A, which, despite higher and more sustained activity than wild-type cyclin E, declined as cells left S-phase (Fig. 6A,B). These data suggested that cyclin E may be differentially sensitive to Fbw7 during the cell cycle and were reinforced by experiments using pharmacologic agents to synchronize MEFs in either early S-phase (aphidicolin) or prometaphase (nocodazole). In this case we found that the amount of cyclin E activity in S-phase cells did not differ appreciably between genotypes, but that the double mutation had large effects on cyclin E activity in prometaphase cells (Fig. 6C,D). Finally, we repeated the serum starvation and release protocol using spontaneously immortalized MEFs, which exhibit more obvious Fbw7-dependent differences in cyclin E abundance because of reduced p21 expression (Loeb et al. 2005). Again we found that cyclin ET74A T393A levels rose continuously in G2/M cells (Fig. 6E). Thus, compared with either wild-type or cyclin ET393A, the double mutation completely abolished cyclin E periodicity as cells reenter the cell cycle from quiescence. Cell cycle kinetics of the three genotypes were similar in each of the three experimental protocols (Fig. 6A,C,E), with one exception. Although immortalized wild-type and cyclin ET74A T393A MEFs exhibited similar kinetics of cell cycle reentry following serum addition, the knockin MEFs were mostly tetraploid and aneuploid (Supplemental Fig. 5C). Although the pattern of cyclin E accumulation in these cells closely mirrors the primary MEFS, we cannot exclude a contribution of this aneuploidy in the knockin cells. In fact, we observed the rapid emergence of tetraploidy and aneuploidy in both lines of knockin MEFs during serial passage, and these changes were most severe with expression the T74A T393A mutation (Supplemental Fig. 5C). These data are consistent with our previous observations that deregulated cyclin E activity promotes genome instability, especially when the p53 pathway is impaired, in this case by immortalization (Spruck et al. 1999; Minella et al. 2002, 2007; Loeb et al. 2005).

Figure 6.

Cell cycle regulation of cyclin ET74A T393A expression and activity. (A) MEFs were synchronized by serum starvation and then released by serum addition and harvested at the indicated times. Cyclin E abundance and kinase activity are shown. Flow cytometry was performed from cells fixed at the indicated time points and indicated similar cell cycle kinetics among the three genotypes. (B) Kinase activity from A was quantified and plotted relative to starting kinase activity in wild-type MEFs. (C) Aphidicolin- and nocodazole-synchronized MEFs were harvested and subjected to cell cycle, immunoblot, and kinase activity analyses as in A. (D) Kinase activity was quantified and normalized to activity measured in the aphidicolin-synchronized wild-type sample. (E) Spontaneously immortalized wild-type and cyclin ET74A T393A MEFs were synchronized similarly as in A and harvested for immunoblot and cell cycle analyses to compare cyclin E abundance at the indicated times. (*) Background band.

Discussion

Both degrons regulate cyclin E activity in vivo

We used targeted mutations in the mouse cyclin E gene to examine the roles of the two cyclin E CPDs in regulating cyclin E activity in vivo. Indeed, although many previous studies suggested that mutation of the high affinity C-terminal degron would be sufficient to block cyclin E degradation by Fbw7 (Clurman et al. 1996; Won and Reed 1996; Welcker et al. 2004; Ye et al. 2004), this is not the case. Instead, we found that the “weaker” N-terminal degron plays a critical role in regulating cyclin E stability. Several mechanisms might account for the physiologic consequences of the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation compared with the cyclin ET393A mutation. For example, the two CPDs may provide (partially) redundant degradation signals; thus, mutation of both degrons is needed to fully prevent Fbw7 binding. Alternatively, the N- and C-terminal degrons might function as independent and possibly tissue-specific modules that regulate cyclin E stability, perhaps in response to different signaling pathways. Although we cannot distinguish between these two possibilities, we are currently developing a cyclin ET74A strain that will determine if any cyclin ET74A T393A phenotypes result solely from the N-terminal degron mutation.

In related transfection-based studies, we have found one context in which both degrons may coordinately interact with Fbw7, and this depends upon Fbw7 dimerization (Welcker and Clurman 2008; M. Welcker and B.E. Clurman, unpubl.). When the C-terminal degron is fully phosphorylated on both T380 and S384, cyclin E can efficiently bind to Fbw7 monomers, even when the N-terminal degron is mutated. In contrast, when the C-terminal degron is weakened by an S384A mutation, cyclin E can still bind to Fbw7, but this binding requires an intact N-terminal degron, as well as Fbw7 dimerization. These data have led us to suggest that cyclin E may have alternate modes of interactions with Fbw7 (Welcker and Clurman 2008) and suggest contexts in which the two degrons might cooperatively regulate Fbw7 binding in vivo. The finding that two spatially separated degrons regulate cyclin E degradation may also explain the absence of stabilizing cyclin E mutations in human cancers. That is, mutations that would disable both degrons while keeping the key intervening functional domains intact would likely require multiple independent and rare events.

Erythropoiesis and cyclin E deregulation

Hematopoietic tissues are highly proliferative, express low amounts of CDK inhibitors, and contain readily detectable cyclin E activity (Loeb et al. 2005). It was thus not surprising to find that the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation increases cyclin E abundance and activity in spleen, bone marrow, and thymus. We note that a recent study in which Fbw7 was conditionally deleted from thymocytes did not reveal increased cyclin E abundance (Onoyama et al. 2007). Perhaps this discrepancy involves the different populations of thymocytes targeted by the T74A T393A mutation (constitutive) and the conditional Fbw7 deletion (driven by an LCK-Cre transgene). Despite similar elevations in cyclin E activity in all three tissues, the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation specifically disrupts erythropoiesis while having no discernable consequences on lymphocyte or myeloid cell proliferation or development. We also enumerated “side population” cells in the bone marrow, which are highly enriched for hematopoietic stem cells, and found no differences attributable to either cyclin E mutation (data not shown). In contrast, cyclin ET74A T393A expression caused a large expansion of abnormally cycling red cell precursors in the spleen and bone marrow, and this is accompanied by impaired erythroid differentiation, increased apoptosis, and dysplasia.

Why might red cell precursors be uniquely sensitive to abnormal cyclin E phosphorylation? One possibility is that different cell types are able to tolerate varying thresholds of cyclin E activity. However, another possibility is that down-regulation of cyclin E activity plays a critical role in erythropoiesis and that this may be controlled through tissue-specific T74 phosphorylation pathways. Thus, cyclin E inactivation may be required for erythroid cells to exit the cell cycle during their differentiation program, and when this is prevented, the result is abnormal cell division and impaired differentiation.

Other studies have shown the importance of the Retinoblastoma pathway, which includes cyclin E, in red cell precursors. Mice with Rb deletions exhibit severe defects in red blood cell maturation (Iavarone et al. 2004; Spike et al. 2004; Dirlam et al. 2007; Wenzel et al. 2007; Sankaran et al. 2008), and this may be due, in part, to deregulated activity of the E2F-2 transcription factor (Dirlam et al. 2007). The Rb-null and cyclin ET74A T393A red cell phenotypes share some features. For example, Rb deletion leads to increased S-phase fraction in sorted Ter119+ CD71+ red cell precursors (Dirlam et al. 2007), albeit less so than the cyclin ET74A T393A mutation (Fig. 2E). Moreover, mice transplanted with Rb-null fetal liver cells develop expanded Ter119+ CD71+ erythroids (Spike et al. 2004). However, there are also significant phenotypic differences (e.g., dysplastic erythroids are prominent in cyclin ET74A T393 mice, whereas conditional Rb-deletion in red cells leads to the appearance of Howell–Jolly bodies [red blood cell micronuclei] in the peripheral blood; Sankaran et al. 2008). The relationship between cyclin E and Rb is complex; although cyclin E inactivates Rb, Rb-loss increases cyclin E mRNA expression. Thus, it remains unclear to what extent the Rb-null red cell phenotype may involve cyclin E activation or, vice versa, how much of the cyclin ET74A T393A phenotype may result from Rb inactivation.

The red cell disorder that develops in cyclin ET74A T393A mice shares many features with early stages of human myelodysplasia, such as refractory anemia. Thus, one important implication of our work is the possibility that cyclin E deregulation may play a role in the pathogenesis of human myelodysplasia and related diseases. Importantly, oncogenic mutations implicated in human myelodysplastic syndromes are likely to effect cyclin E activity. For example, oncogenic Ras mutations may increase cyclin E activity through both increased synthesis and decreased degradation (Leone et al. 1997; Minella et al. 2005).

Epithelial cell proliferation in cyclin ET74A T393A mice

Like hematopoietic tissues, epithelia are also highly proliferative and exhibit abnormal cell division when cyclin E degradation is impaired. However, despite widespread hyperproliferation, cyclin ET74A T393A mammary epithelia do not develop morphologic abnormalities or neoplasms. One mechanism of tissue homeostasis that counters cyclin E-driven cell proliferation is apoptosis, which is increased in cyclin ET74A T393A mammary epithelia. Similarly, we have found that stabilized cyclin E in human mammary epithelial cells cultured in three-dimensional basement membrane extract drive proliferation and apoptosis (A.C. Minella and B.E. Clurman, in prep.), suggesting a linkage between cyclin E-induced proliferation and cell death. Unlike hematopoietic tissues, we found similar abnormalities in epithelial cell division in cyclin ET393A and cyclin ET74A T393A mice, with the exception of delayed mammary gland involution, which occurs only when both degrons are mutated. Thus, epithelial tissues may be more sensitive to cyclin E deregulation than blood cells, or perhaps the signaling pathways that phosphorylate T74 play a more prominent role in cyclin E regulation during involution than in proliferating mammary glands.

Cyclin E periodicity is regulated by cyclin E phosphorylation within both degrons

Our studies in MEFs show that cyclin E phosphorylation is required for its normal oscillation during cell cycle reentry and that disruption of both degrons is required to fully disrupt cyclin E periodicity. When only the C-terminal degron is disabled, cyclin E activity reaches a higher and sustained peak compared with wild-type cyclin E, but it remains sensitive to Fbw7 (Fig. 6), and its abundance and activity decline as cells progress beyond S-phase. In contrast, cyclin ET74A T393A continues to increase throughout G2/M. The finding that cyclin E degron mutations have minimal effects in G1/S (when cyclin E normally accumulates) and largest effects in G2/M (when cyclin E normally declines) suggests that cyclin E phosphorylation within both degrons comprises an important mechanism that establishes cyclin E’s sensitivity to Fbw7 and thus its periodicity during the cell cycle. Accordingly, mutation of both phosphorylation sites abolishes normal cyclin E periodicity.

What accounts for the variable consequences of cyclin E phosphorylation during the cell cycle? Our ongoing studies in Fbw7-null human cells indicate that cyclin E-CDK2 specific activity, and thus the stoichiometry of cyclin E degron phosphorylation, varies greatly during the cell cycle (Grim et al. 2008). We find that cyclin E-CDK specific activity is very high in Fbw7-null prometaphase cells compared with S-phase cells, and this leads to increased cyclin E autophosphorylation. Furthermore, in agreement with previous work (Gu et al. 1992), we find that the amount of CDK2 inhibitory phosphorylation correlates closely with these changes in CDK2 specific activity. We thus speculate that these changes in CDK2 specific activity establish the amount of cyclin E autophosphorylation and thus the relative consequences of the cyclin E degron mutations during the cell cycle.

Cyclin E regulation by Fbw7 may serve different functions at different points in the cell cycle. Mammalian cells contain a large fraction of cyclin E in catalytically inactive complexes in G1/S, and thus only a small pool of active cyclin E is sensitive to Fbw7 in these cells. However, because deregulated cyclin E activity delays S-phase progression, degradation of active cyclin E-CDK2 by Fbw7 likely plays an important role in normal G1/S control. Why might cyclin E be hypersensitive to Fbw7 in G2/M cells? One possibility is to insure that cyclin E-CDK2 activity is absent during mitosis. Mitotic CDK activity is normally controlled by the anaphase-promoting complex, but cyclin E is not an APC substrate, and decreased cyclin E phosphorylation (or Fbw7 mutations) may result in APC-resistant CDK activity in mitosis, which inhibits APC activity and impairs mitosis (Rajagopalan et al. 2004; Keck et al. 2007). Thus, misregulation of cyclin E in both S-phase and mitotic cells may contribute to the genetic instability that results when cyclin E cannot be phosphorylated within its two degrons.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that cyclin E phosphorylation within both degrons regulates its degradation by the Fbw7 pathway and that loss of this proteolytic pathway causes tissue-specific hyperproliferation in vivo. One known consequence of nondegradable cyclin E expression is the development of genomic instability, and this is thought to play a crucial role in cyclin E-associated tumorigenesis. We have now found that another consequence of preventing cyclin E degradation in vivo is hyperproliferation and speculate that this may also contribute to tumorigenesis by facilitating the expansion of cells that have acquired, or are poised to acquire, genomic instability. However, because cyclin E-induced hyperproliferation is countered by apoptosis, tumors, at least in some tissues, may also need to disable this cellular response before aberrant cyclin E activity can drive cellular expansion in vivo.

Materials and methods

Mice

Construction of the targeting vector for cyclin ET74A T393A mice was performed as described by Loeb et al. (2005). Embryonic stem cell colonies were selected in G418 (Invitrogen) and screened for homologous recombination by PCR and confirmed by Southern blot hybridization. Two ES cell clones were used for blastocyst injection of C57/BL6 females. Germline transmission was identified by PCR screening of male chimeras. The LoxP Neo cassette was excised by crossing with Cre-expressing MORE mice (provided by P. Soriano). Cyclin ET74A T393A mice were backcrossed into the laboratory stock 129Sv strain and to the C57/BL6 strain for six generations. Control mice for all experiments included cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET393A mice, which are maintained in both C57/BL6 and 129Sv backgrounds. For studies of murine mammary tissues, all experiments were performed using breeders from each genotype set up in parallel. For the involution studies, females were housed together and kept separate from males to help maintain synchrony of estrous cycles. For BrdU labeling, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 mg/kg BrdU and sacrificed 2–4 h following injection. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center IACUC approved all mouse studies. Euthanasia was performed by CO2 asphyxiation according to IACUC guidelines.

Antibodies

Antibodies used in these studies were obtained from the following sources: affinity-purified polyclonal anti-cyclin E (Clurman et al. 1996), anti-Grb2 monoclonal (BD Biosciences), anti-Ki67 polyclonal (Sp6—Biocare), anti-BrdU monoclonal (Accurate) for IHC, anti-cleaved caspase 3 polyclonal (Biocare), and for flow cytometry studies, anti-CD71, anti-Ter119, anti-Mac1, anti-F480, anti-GR1, anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-B220, fluorophore-conjugated anti-BrdU and anti-Annexin V (all from BD Biosciences).

Preparation of MEFs and tissue culture

Primary MEFs were prepared by standard methods at days 12–14 p.c. (Malek et al. 2001). Immortalized cells were obtained by serial passages on a 3T3 protocol (Todaro and Green 1963). Cell synchronization and cell cycle analyses were performed using serum starvation/contact inhibition methodologies as previously described (Loeb et al. 2005) or overnight treatments with aphidicolin (5 mg/mL) or nocodazole (40 ng/mL). Cell extracts, Western blots, and kinase assays were prepared using NP40 lysis buffer (Minella et al. 2005), and tissue extracts were prepared by lysing snap-frozen tissues in RIPA buffer (Loeb et al. 2005). RNA was obtained from mouse cells and tissues using Qiagen RNAeasy kits, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed on reverse-transcribed template, using commercially obtained Taqman primer/probe sets for mouse cyclin E, Fbw7, and real-time PCR instruments (Applied Biosystems).

Hematopoietic analyses

Spleens, thymuses, bilateral femurs, and tibiae were obtained from age- and sex-matched mice. Bone marrow was harvested by grinding bones using a mortar/pestle, suspending cells in 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and filtering suspensions through 70-μm nylon cell strainers. Splenocytes and thymocytes were harvested by gently mashing between two glass slides and resuspending in 2% FBS. For erythroid immunophenotyping studies, red blood cell lysis was not performed. Following manual counting of nucleated cells using Tuerk’s stain (Sigma), aliquots of live splenocytes and bone marrow cells were stained with various combinations of the aforementioned antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Side populations (LSK-SP cells) were enumerated with the addition of Hoechst 33342 dye (Calbiochem) and gating was as described previously (Dallas et al. 2005). Cell sorting of live, unfixed cells was performed on a Vantage (BD) cell sorter, and cell cycle analyses were performed by subsequent fixing and staining with either DAPI or propidium iodide. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Stanford University), and gating of erythroid progenitor cells on the basis of CD71 and Ter119 expression was performed as previously described (Socolovsky et al. 2001; Liu et al. 2006). Morphologic analyses were performed on peripheral blood and whole bone marrow using Wright-Giemsa stain solution (Richard-Allan Scientific).

Bone marrow transplants

Whole bone marrow was obtained from age-matched cyclin Ewt and cyclin ET74A T393A donor mice (Ly5.2) and mixed with competitor wild-type bone marrow cells (Ly5.1, obtained from SJL/J mice). Cells were manually counted and pooled from four donors of each genotype. We transplanted 1 × 106 nucleated donor cells and 1 × 105 competitor cells into each of four recipient mice per genotype that received 10 Gy of total body irradiation via cesium source 24 h prior to transplant. Transplant recipients were followed periodically with peripheral blood analyses, and at 17 wk post-transplant, mice were euthanized and bone marrow harvested for flow cytometry analysis.

Mammary studies

Females were bred in parallel and kept separately from males following identification of pregnancies. For involution studies, litters were removed and fostered at days 14–21 post-partum, and mice were euthanized at days 5, 16, and 21 following weaning. Mammary tissues were harvested and either formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, or fixed and mounted on glass slides for whole mount staining using Meyer’s haematoxylin solution (Sigma). During involution, serum prolactin and 17-β-estradiol levels were monitored using ELISA detection assays (Bioquant).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dave Flowers and Cynthia Nourigat for expert technical assistance and Janis Abkowitz, Sioban Keel (University of Washington), and John Crispino (Northwestern University) for helpful discussions. Mitra Bhattacharyya and Ganesan Keerthivasan (Northwestern University) provided assistance with ELISAs and enucleation assays, respectively. This work is supported by the NIH (CA102742 and HL084205) and a Burroughs Wellcome Foundation Clinical Scientist Award (B.E.C.) and NIH Research Career Awards K08CA101800 (A.C.M.) and K08ES00382 (K.R.L.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1650208.

References

- Akli S., Van Pelt C.S., Bui T., Multani A.S., Chang S., Johnson D., Tucker S., Keyomarsi K. Overexpression of the low molecular weight cyclin E in transgenic mice induces metastatic mammary carcinomas through the disruption of the ARF-p53 pathway. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7212–7222. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clurman B.E., Sheaff R.J., Thress K., Groudine M., Roberts J.M. Turnover of cyclin E by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is regulated by cdk2 binding and cyclin phosphorylation. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1979–1990. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas M.H., Varnum-Finney B., Delaney C., Kato K., Bernstein I.D. Density of the Notch ligand Δ1 determines generation of B and T cell precursors from hematopoietic stem cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1361–1366. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirlam A., Spike B.T., Macleod K.F. Deregulated E2f-2 underlies cell cycle and maturation defects in retinoblastoma null erythroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:8713–8728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01118-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulic V., Lees E., Reed S.I. Association of human cyclin E with a periodic G1-S phase protein kinase. Science. 1992;257:1958–1961. doi: 10.1126/science.1329201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duronio R.J., O'Farrell P.H. Developmental control of the G1 to S transition in Drosophila: Cyclin E is a limiting downstream target of E2F. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1456–1468. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm-Reed S., Spruck C.H., Sangfelt O., van Drogen F., Mueller-Holzner E., Widschwendter M., Zetterberg A., Reed S.I. Mutation of hCDC4 leads to cell cycle deregulation of cyclin E in cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:795–800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y., Eaton E.N., Picon M., Roberts J.M., Lundberg A.S., Gifford A., Sardet C., Weinberg R.A. Regulation of cyclin E transcription by E2Fs and retinoblastoma protein. Oncogene. 1996;12:1173–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y., Yu Q., Sicinska E., Das M., Schneider J.E., Bhattacharya S., Rideout W.M., Bronson R.T., Gardner H., Sicinski P. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:431–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y., Lee Y.M., Welcker M., Swanger J., Zagozdzon A., Winer J.D., Roberts J.M., Kaldis P., Clurman B.E., Sicinski P. Kinase-independent function of cyclin E. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim J.E., Gustafson M.P., Hirata R.K., Hagar A.C., Swanger J., Welcker M., Hwang H.C., Ericcson J., Russell D.W., Clurman B.E. Isoform- and cell cycle-dependent substrate degradation by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J. Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802076. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y., Rosenblatt J., Morgan D.O. Cell cycle regulation of CDK2 activity by phosphorylation of Thr160 and Tyr15. EMBO J. 1992;11:3995–4005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao B., Oehlmann S., Sowa M.E., Harper J.W., Pavletich N.P. Structure of a Fbw7-Skp1-cyclin E complex: Multisite-phosphorylated substrate recognition by SCF ubiquitin ligases. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H.C., Clurman B.E. Cyclin E in normal and neoplastic cell cycles. Oncogene. 2005;24:2776–2786. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A., King E.R., Dai X.M., Leone G., Stanley E.R., Lasorella A. Retinoblastoma promotes definitive erythropoiesis by repressing Id2 in fetal liver macrophages. Nature. 2004;432:1040–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature03068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsunky H., Geisen C., Schmidt T., Haas K., Zevnik B., Gau E., Moroy T. Oncogenic potential of cyclin E in T-cell lymphomagenesis in transgenic mice: Evidence for cooperation between cyclin E and Ras but not Myc. Oncogene. 1999;18:7816–7824. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck J.M., Summers M.K., Tedesco D., Ekholm-Reed S., Chuang L.C., Jackson P.K., Reed S.I. Cyclin E overexpression impairs progression through mitosis by inhibiting APC(Cdh1) J. Cell Biol. 2007;178:371–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp D.M., Schaefer L.K., Ye X., Keyomarsi K., Chu C., Harper J.W., Elledge S.J. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2001;294:173–177. doi: 10.1126/science.1065203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koff A., Giordano A., Desai D., Yamashita K., Harper J.W., Elledge S., Nishimoto T., Morgan D.O., Franza B.R., Roberts J.M. Formation and activation of a cyclin E-cdk2 complex during the G1 phase of the human cell cycle. Science. 1992;257:1689–1694. doi: 10.1126/science.1388288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone G., DeGregori J., Sears R., Jakoi L., Nevins J.R. Myc and Ras collaborate in inducing accumulation of active cyclin E/Cdk2 and E2F. Nature. 1997;387:422–426. doi: 10.1038/387422a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Pop R., Sadegh C., Brugnara C., Haase V.H., Socolovsky M. Suppression of Fas-FasL coexpression by erythropoietin mediates erythroblast expansion during the erythropoietic stress response in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:123–133. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb K.R., Kostner H., Firpo E., Norwood T.K.D.T., Clurman B.E., Roberts J.M. A mouse model for cyclin E-dependent genetic instability and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek N.P., Sundberg H., McGrew S., Nakayama K., Kyriakides T.R., Roberts J.M. A mouse knock-in model exposes sequential proteolytic pathways that regulate p27Kip1 in G1 and S phase. Nature. 2001;413:323–327. doi: 10.1038/35095083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minella A.C., Swanger J., Bryant E., Welcker M., Hwang H., Clurman B.E. p53 and p21 form an inducible barrier that protects cells against cyclin E-cdk2 deregulation. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1817–1827. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minella A.C., Welcker M., Clurman B.E. Ras activity regulates cyclin E degradation by the Fbw7 pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:9649–9654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503677102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minella A.C., Grim J.E., Welcker M., Clurman B.E. p53 and SCFFbw7 cooperatively restrain cyclin E-associated genome instability. Oncogene. 2007;26:6948–6953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg K.H., Bell D.W., Wahrer D.C., Haber D.A., Hariharan I.K. Archipelago regulates Cyclin E levels in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Nature. 2001;413:311–316. doi: 10.1038/35095068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash P., Tang X., Orlicky S., Chen Q., Gertler F.B., Mendenhall M.D., Sicheri F., Pawson T., Tyers M. Multisite phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor sets a threshold for the onset of DNA replication. Nature. 2001;414:514–521. doi: 10.1038/35107009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nateri A.S., Riera-Sans L., Da Costa C., Behrens A. The ubiquitin ligase SCFFbw7 antagonizes apoptotic JNK signaling. Science. 2004;303:1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.1092880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg C., Li J., Pauley A., Wolf E., Gurney M., Lendahl U. The Notch intracellular domain is ubiquitinated and negatively regulated by the mammalian Sel-10 homolog. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35847–35853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani K., DeGregori J., Nevins J.R. Regulation of the cyclin E gene by transcription factor E2F1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:12146–12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoyama I., Tsunematsu R., Matsumoto A., Kimura T., de Alboran I.M., Nakayama K., Nakayama K.I. Conditional inactivation of Fbxw7 impairs cell-cycle exit during T cell differentiation and results in lymphomatogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2875–2888. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlicky S., Tang X., Willems A., Tyers M., Sicheri F. Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2003;112:243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi T., Beck A.R., Rougier N., McNeil T., Lucian L., Werb Z., Amati B. Cyclins E1 and E2 are required for endoreplication in placental trophoblast giant cells. EMBO J. 2003;22:4794–4803. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan H., Jallepalli P.V., Rago C., Velculescu V.E., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B., Lengauer C. Inactivation of hCDC4 can cause chromosomal instability. Nature. 2004;428:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran V.G., Orkin S.H., Walkley C.R. Rb intrinsically promotes erythropoiesis by coupling cell cycle exit with mitochondrial biogenesis. Genes & Dev. 2008;22:463–475. doi: 10.1101/gad.1627208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr C.J., Roberts J.M. CDK inhibitors: Positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J.D., Gurian-West M., Clurman B., Roberts J.M. Cullin-3 targets cyclin E for ubiquitination and controls S phase in mammalian cells. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:2375–2387. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.P., Henze M., Lee J.A., Osborn K.G., Keck J.M., Tedesco D., Bortner D.M., Rosenberg M.P., Reed S.I. Deregulated cyclin E promotes p53 loss of heterozygosity and tumorigenesis in the mouse mammary gland. Oncogene. 2006;25:7245–7259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolovsky M., Nam H., Fleming M.D., Haase V.H., Brugnara C., Lodish H.F. Ineffective erythropoiesis in Stat5a−/−5b−/− mice due to decreased survival of early erythroblasts. Blood. 2001;98:3261–3273. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike B.T., Dirlam A., Dibling B.C., Marvin J., Williams B.O., Jacks T., Macleod K.F. The Rb tumor suppressor is required for stress erythropoiesis. EMBO J. 2004;23:4319–4329. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruck C.H., Won K.A., Reed S.I. Deregulated cyclin E induces chromosome instability. Nature. 1999;401:297–300. doi: 10.1038/45836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruck C.H., Strohmaier H., Sangfelt O., Muller H.M., Hubalek M., Muller-Holzner E., Marth C., Widschwendter M., Reed S.I. hCDC4 gene mutations in endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4535–4539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmaier H., Spruck C.H., Kaiser P., Won K.A., Sangfelt O., Reed S.I. Human F-box protein hCdc4 targets cyclin E for proteolysis and is mutated in a breast cancer cell line. Nature. 2001;413:316–322. doi: 10.1038/35095076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro G.J., Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J. Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsihlias J., Kapusta L., Slingerland J. The prognostic significance of altered cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in human cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999;50:401–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C.J. Involution: Apoptosis and tissue remodelling that convert the mammary gland from milk factory to a quiescent organ. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:203. doi: 10.1186/bcr1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Jin J., Schlisio S., Harper J.W., Kaelin W. The v-Jun point mutation allows c-Jun to escape GSK3-dependent recognition and destruction by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welcker M., Clurman B.E. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: A tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welcker M., Singer J., Loeb K.R., Grim J., Bloecher A., Gurien-West M., Clurman B.E., Roberts J.M. Multisite phosphorylation by Cdk2 and GSK3 controls cyclin E degradation. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:381–392. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welcker M., Orian A., Jin J., Grim J.E., Harper J.W., Eisenman R.N., Clurman B.E. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel P.L., Wu L., de Bruin A., Chong J.L., Chen W.Y., Dureska G., Sites E., Pan T., Sharma A., Huang K., et al. Rb is critical in a mammalian tissue stem cell population. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:85–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.1485307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won K.A., Reed S.I. Activation of cyclin E/CDK2 is coupled to site-specific autophosphorylation and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of cyclin E. EMBO J. 1996;15:4182–4193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yada M., Hatakeyama S., Kamura T., Nishiyama M., Tsunematsu R., Imaki H., Ishida N., Okumura F., Nakayama K., Nakayama K.I. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;23:2116–2125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Nalepa G., Welcker M., Kessler B., Spooner E., Qin J., Elledge S.J., Clurman B.E., Harper J.W. Recognition of phosphodegron motifs in human cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50110–50119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]