Abstract

Interference-dependent crossing over in yeast and mammalian meioses involves the mismatch repair protein homologs MSH4-MSH5 and MLH1-MLH3. The MLH3 protein contains a highly conserved metal-binding motif DQHA(X)2E(X)4E that is found in a subset of MLH proteins predicted to have endonuclease activities (Kadyrov et al. 2006). Mutations within this motif in human PMS2 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae PMS1 disrupted the endonuclease and mismatch repair activities of MLH1-PMS2 and MLH1-PMS1, respectively (Kadyrov et al. 2006, 2007; Erdeniz et al. 2007). As a first step in determining whether such an activity is required during meiosis, we made mutations in the MLH3 putative endonuclease domain motif (-D523N, -E529K) and found that single and double mutations conferred mlh3-null-like defects with respect to meiotic spore viability and crossing over. Yeast two-hybrid and chromatography analyses showed that the interaction between MLH1 and mlh3-D523N was maintained, suggesting that the mlh3-D523N mutation did not disrupt the stability of MLH3. The mlh3-D523N mutant also displayed a mutator phenotype in vegetative growth that was similar to mlh3Δ. Overexpression of this allele conferred a dominant-negative phenotype with respect to mismatch repair. These studies suggest that the putative endonuclease domain of MLH3 plays an important role in facilitating mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over.

IN most organisms, segregation of homologous chromosomes in the meiosis I (MI) division requires crossing over between homologs. The physical manifestations of these crossover events, chiasmata, provide the contacts between homologous chromosomes that are necessary for segregation (Jones 1987). These contacts ensure the generation of a bipolar spindle in which tension is generated at the kinetochores (Maguire 1974). The subsequent release of sister-chromatid connections at chiasmata is thought to be critical for the MI division (Storlazzi et al. 2003; Yu and Koshland 2005). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two crossovers rarely occur within the same genetic interval (positive crossover interference) and smaller chromosomes tend to display less positive interference than larger ones (Mortimer and Fogel 1974; Kaback et al. 1999; Shinohara et al. 2003). The result of this regulation is that every chromosome, regardless of size, receives at least one reciprocal exchange (Jones 1987).

In S. cerevisiae, meiotic crossing over is induced by programmed double-strand breaks that are processed into crossovers through the formation and disappearance of single-end invasion and double-Holliday junction (dHJ) intermediates (see Oh et al. 2007). The majority of the meiotic crossovers are interference dependent and involve the MutS mismatch repair (MMR) homologs MSH4-MSH5 and the MutL mismatch repair homologs MLH1-MLH3 (De Los Santos et al. 2003; Argueso et al. 2004). Strains bearing mutations in these genes display a reduction in crossing over, but are functional in meiotic gene conversion. S. cerevisiae also has an additional interference-independent meiotic crossover pathway involving the endonuclease MUS81-MMS4 (De Los Santos et al. 2003). The MUS81-MMS4 endonuclease is thought to create crossovers either by direct resolution of the Holliday junction (HJ) or by cleaving D-loops and half-HJ structures formed in a pre-HJ intermediate (Boddy et al. 2001; Hollingsworth and Brill 2004; Gaskell et al. 2007). Although the components of both pathways are present in mice and humans, genetic, cytological, and biochemical studies suggest that meiotic crossovers in the mouse occur primarily through an interference-dependent pathway involving MSH4-MSH5 and MLH1-MLH3 (Woods et al. 1999; Lipkin et al. 2002; Santucci-Darmanin et al. 2002; Abraham et al. 2003; Ciccia et al. 2003).

Genetic, biochemical, and cell biological data in yeast and mice suggest that MSH4-MSH5 functions prior to MLH1-MLH3 in interference-dependent meiotic crossing over (Hunter and Borts 1997; Wang et al. 1999; Santucci-Darmanin et al. 2002; Argueso et al. 2004):

Cytological studies in mice have shown that MSH4-MSH5 foci are observed at zygotene, MLH3 is associated with recombination nodules at early pachytene, and MLH1 then associates with MLH3 in mid-pachytene (Lipkin et al. 2002; Moens et al. 2002; Kolas et al. 2005).

Analysis of mouse and human spermatocytes indicated that the MLH1 foci on pachytene chromosomes correspond to chiasmata/crossover sites. These foci are thought to be associated with a subset of MSH4-MSH5 foci that become crossovers (Baker et al. 1996; Barlow and Hultén 1998).

Biochemical studies using mouse meiotic cell extracts showed that MSH4 co-immunoprecipitated with MLH3 (Santucci-Darmanin et al. 2002).

Consistent with MSH4-MSH5 functioning prior to MLH1-MLH3, genetic analysis in yeast showed that msh5Δ mlh1Δ double mutants display crossover defects similar to those seen in msh5Δ mutants (Wang et al. 1999; Argueso et al. 2004).

The MSH4-MSH5 and MLH1-MLH3 proteins have also been shown to act as pro-crossover factors that act in opposition to SGS1 to promote crossing over at designated chromosome sites and to prevent aberrant crossing over (Jessop et al. 2006; Oh et al. 2007). The mechanisms by which MSH4-MSH5 and MLH1-MLH3 accomplish these tasks are unknown. One hypothesis is that MSH4-MSH5 stabilizes Holliday junction intermediates (Snowden et al. 2004) and MLH1-MLH3 activates and directs an unknown downstream factor that resolves HJ intermediates into crossovers (Hoffmann and Borts 2004; Whitby 2005).

Human MLH1-PMS2 (hMutLα) and yeast MLH1-PMS1 contain an ATP·Mn2+-dependent latent endonuclease activity that is essential for mismatch repair, possibly by providing access for EXO1 to participate in excision steps (Kadyrov et al. 2006, 2007). This activity has also been hypothesized to act in strand discrimination steps in organisms that lack MutH-directed mismatch repair (Kadyrov et al. 2007). The DQHA(X)2E(X)4E metal-binding motif in the human PMS2 and yeast PMS1 subunits of MutLα was shown to be critical for this activity. Mutations in this site in yeast and humans (pms2-D699N, pms2-E705K, pms1-E707K) abolish MutLα endonuclease activities, resulting in a defect in mismatch repair (Kadyrov et al. 2006, 2007; Deschênes et al. 2007). In addition, like pms1Δ, the pms1-E707K yeast mutant is defective in suppressing recombination between divergent DNA sequences and in the mismatch-repair-dependent response to DNA methylation damage (Erdeniz et al. 2007).

The MLH3 homologs in yeast and humans contain the highly conserved metal-binding motif implicated in MutLα endonuclease activity (Kadyrov et al. 2006). We analyzed point mutations within the endonuclease domain of S. cerevisiae MLH3 for their effect on meiotic crossing over and the repair of frameshift mutation intermediates. Our genetic and biochemical analyses suggest that the MLH3 endonuclease domain is important for both processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media:

Yeast strains were grown in either YPD (yeast extract, peptone, dextrose) media or minimal selective media (Rose et al. 1990) and transformed as described previously (Gietz et al. 1995). YPD media was supplemented with geneticin (Invitrogen, San Diego) and nourseothricin (Hans-Knoll Institute fur Naturstoff-Forschung) as described previously (Wach et al. 1994; Goldstein and McCusker 1999).

MLH3 plasmids:

Details on how to make all vectors are available upon request. All mutant alleles were constructed by Quick Change (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The mutant alleles were subcloned into wild-type vector backbones and verified by DNA sequencing (Cornell BioResource Center).

SK1 MLH3 containing the 1.5-kb KANMX4 fragment inserted 40 bp downstream of the MLH3 stop codon was cloned into pUC18 to create the single-step integrating plasmid pEAI254. This plasmid was mutagenized by Quick Change (Stratagene) to create plasmids pEAI253 (mlh3-E529K), pEAI252 (mlh3-D523N), and pEAI251 (mlh3-D523N, -E529K).

pEAE220 (GAL10-MLH3, 2μ, URA3) contains the GAL10 promoter driving expression of S288c MLH3. pEAE282 (mlh3-D523N) and pEAE289 (mlh3-E529K) are pEAE220 derivatives created using Quick Change. These plasmids were used in the dominant-negative experiments presented in Table 3. pEAE280 (GAL10-HA-MLH3, 2μ, URA3) is a derivative of pEAE220 that contains an HA-tag (YPYDVPDYA) inserted after the first codon of S288c MLH3. pEAE283 (HA-mlh3-D523N) and pEAE290 (HA-mlh3-E529K) are derivatives of pEAE280 created by Quick Change. These plasmids were used in the Western blots presented in Figure 4A. pEAE279 (GALPGK-HA-MLH3, 2μ, leu2-d) was constructed by inserting the HA-MLH3 sequence from pEAE280 into the pMMR20 backbone (GALPGK, 2μ, leu2-d, a kind gift of L. Prakash). pEAE287 (GALPGK-HA-mlh3-D523N, 2μ, leu2-d) and pEAE291 (GALPGK-HA-mlh3-E529K, 2μ, leu2-d) are derivatives of pEAE279 that were constructed by Quick Change. These vectors were used for the chitin bead column chromatography presented in Figure 4B.

TABLE 3.

Overexpression of mlh3-D523N confers a strong dominant-negative phenotype in lys2:insE-A14 reversion assays

| Genotype, 2μ expression plasmid | n | Mutation rate (10−7), (95% C. I.) | Relative to wild type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type, empty vector | 16 | 2.3 (0.97–3.6) | 1 |

| Wild type, pGAL10-MLH1 | 15 | 1920 (1550–2820) | 835 |

| Wild type, pGAL10-MLH3 | 13 | 2590 (1940–3530) | 1120 |

| Wild type, pGAL10-mlh3-D523N | 15 | 4200 (3080–5880) | 1820 |

| Wild type, pGAL10-mlh3-E529K | 12 | 5.5 (2.9–8.8) | 2.4 |

| mlh1Δa | 20 | 20,200 (16,800–23,500) | 8770 |

EAY1269 (S288c lys2∷insE-A14) transformed with pEAO34 (empty 2μ vector), pEAE102 (GAL10-MLH1, 2μ), pEAE220 (GAL10-MLH3, 2μ), pEAE282 (GAL10-mlh3-D523N, 2μ), or pEAE289 (GAL10-mlh3-E529K, 2μ) was examined for reversion to Lys+ (materials and methods). The mutation rates, actual (95% C. I.) and relative to EAY1269 transformed with pEAO34, are presented. n, number of independent cultures tested.

Mutation rate determined for EAY1366.

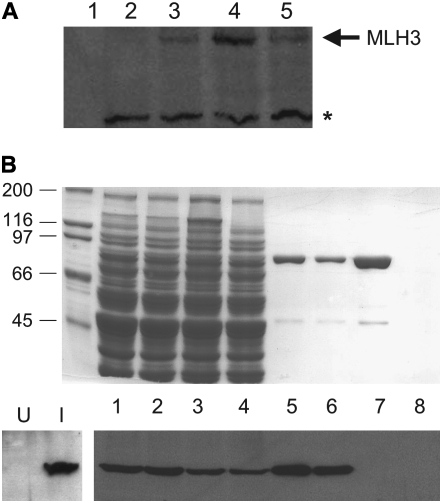

Figure 4.—

Epitope-tagged MLH3 and mlh3-D523N are stably expressed and interact with MLH1. (A) Crude extracts from galactose-induced yeast containing GAL10-HA-MLH3-2μ and mlh3 derivatives were analyzed in Western blots (8% SDS–PAGE) probed with αHA antibody (materials and methods). Lane 1, purified MLH1-PMS1 (2 μg). Lanes 2–5, cell extracts from strains expressing untagged MLH3 (lane 2), HA-mlh3-E529K (lane 3), HA-mlh3-D523N (lane 4), and HA-MLH3 (lane 5). The asterisk indicates a cross-reacting, nonspecific band. (B) Partial purification of MLH1-HA-MLH3 and MLH1-HA-mlh3-D523N complexes by chitin bead column chromatography. Eluates from chitin bead columns separated on 8% SDS–PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue (top) and Western blot analysis with αHA antibody (bottom). Crude extracts are from uninduced (U) or galactose-induced (I) yeast containing GAL10-HA-MLH3-2μ-leu2-d. Lanes 1–4, input extract (8 μl loaded from 50 to 60 ml) from cells overexpressing MLH1 and HA-MLH3 (lane 1), MLH1 and HA-mlh3-D523N (lane 2), MLH1 and HA-mlh3-E529K (lane 3), and HA-MLH3 alone (lane 4). Lanes 5–8, pooled chitin bead eluate fractions (8 μl loaded from 5.5- to 7.0-ml fractions) derived from extracts containing overexpressed MLH1 and HA-MLH3 (lane 5), MLH1 and HA-mlh3-D523N (lane 6), MLH1 and HA-mlh3-E529K (lane 7), and HA-MLH3 alone (lane 8). The sizes of the relevant molecular weight (kDa) standards are indicated.

The following vectors were used in two-hybrid analysis: The target S288C MLH3 plasmid (pEAM98) contains a fusion between the GAL4 activation domain in pGAD10 and residues 481–715 of the MLH3 C terminus (Wang et al. 1999). mlh3 derivatives of pEAM98 (pEAM170-mlh3-D523N, pEAM171-mlh3-E529K, and pEAM169-mlh3-D523N, -E529K) were made using Quick Change.

Tetrad analysis:

The parental SK1 congenic strains EAY1108 (MATa, ho∷hisG, lys2, ura3, leu2∷hisG, trp1∷hisG, URA3-cenXVi, LEU2-chXVi, LYS2-chXVi) and EAY1112 (MATα, ho∷hisG, lys2, ura3, leu2∷hisG, trp1∷hisG, ade2∷hisG, his3∷hisG, TRP1-cenXVi) were mated to create the wild-type diploid reference strain (Argueso et al. 2004). EAY1108/EAY1112 diploids homozygous for mlh3Δ and mms4Δ mutations were created by sequential deletion in the haploid strains using the KANMX4 and NATMX4 selectable markers, respectively (Wach et al. 1994; Goldstein and McCusker 1999). MLH3 endonuclease domain point mutants were created by single-step gene replacement transformation using the SK1-derived mlh3 plasmids described above. For the mutant analyses, at least two independent transformants for each genotype were analyzed.

Mutant derivatives of EAY1108 are EAY1845 (mms4Δ∷NATMX4), EAY1847 (mlh3Δ∷KANMX4), EAY1849 (mlh3-D523N, -E529K∷KANMX4), EAY2026 (mlh3-D523N∷KANMX4), EAY2028 (mlh3-E529K∷KANMX4), EAY2030 (mlh3Δ∷KANMX4, mms4Δ∷NATMX4), EAY2034 (MLH3∷KANMX4) and EAY2273 (mlh3-D523N∷KANMX4, mms4Δ∷NATMX4). Mutant derivatives of EAY1112 are EAY1846 (mms4Δ∷NATMX4), EAY1848 (mlh3Δ∷KANMX4), EAY1850 (mlh3-D523N, -E529K∷KANMX4), EAY2027 (mlh3-D523N∷KANMX4), EAY2029 (mlh3-E529K∷KANMX4), EAY2031 (mlh3Δ∷KANMX4, mms4Δ∷NATMX4), EAY2035 (MLH3∷KANMX4), and EAY2274 (mlh3-D523N∷KANMX4, mms4Δ∷NATMX4).

Diploids created by mating EAY1108 and EAY1112 parental strains and mutant derivatives were sporulated using the zero-growth mating protocol (Argueso et al. 2003). Spore clones were replica plated onto minimal drop-out plates and incubated overnight. Segregation data were analyzed using the recombination analysis software RANA (Argueso et al. 2004). Genetic map distances were determined by the formula of Perkins (1949). Statistical analysis of genetic map distances was done using the Stahl Laboratory Online Tools (http://www.molbio.uoregon.edu/∼fstahl/) and VassarStats (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html).

Two-hybrid analysis:

The L40 strain was cotransformed with the bait vector (pBTM-MLH1) and the target vector pEAM98 or its mutant derivatives pEAM169, pEAM170, and pEAM171. Expression of the lacZ reporter gene was determined by the ortho-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) and color filter assays as described (Pang et al. 1997). Activation of the HIS3 reporter was also measured.

Lys+ reversion assay:

The SK1 isogenic strain EAY1062 (MATa, ho∷hisG, leu2∷hisG, ade2∷LK, his4xB, lys2∷InsE-A14) and MLH3∷KANMX4 (EAY2186), mlh3Δ∷KANMX4 (EAY2037), and mlh3-D523N∷KANMX4 (EAY2036) derivatives were examined for Lys+ reversion (Tran et al. 1997). A total of 16–18 independent cultures from at least three independent transformants were assayed and the mutation rate was determined as described previously (Heck et al. 2006).

To test for dominant-negative effects due to MLH3, mlh3-D523N, and mlh3-E529K overexpression, the S288c strain EAY1269 (MATa, ura3, trp1, lys2∷insE-A14) was transformed with pRS426 (URA3, 2μ), pEAE220 (GAL10-MLH3, URA3, 2μ), pEAE282 (GAL10-mlh3-D523N, URA3, 2μ), pEAE289 (GAL10-mlh3-E529K, URA3, 2μ), and pEAE102 (GAL10-MLH1, URA3, 2μ) plasmids that overexpress the indicated genes (all S288c derived). The mutation rate for mlh1Δ was examined in the S288c strain EAY1366 (MATa, leu2, ura3, trp1, his3, lys2∷insE-A14, mlh1Δ∷KANMX4). For testing Lys + reversion, 12–20 independent cultures from at least three independent transformants were grown from single colonies for 22 hr at 30° in minimal selective media containing 2% sucrose. These cultures were diluted 1:120 in minimal selective media containing 2% sucrose and 2% galactose and then grown for 24 hr at 30°. Appropriate dilutions were then plated on minimal selective media containing 2% galactose and 2% sucrose with or without lysine to determine the mutation rate.

Protein expression and purification:

BJ2168 (MATa, ura3-52, trp1-289, leu2-3,-112, prb1-1122, prc1-407, pep4-3) transformed with pMH1(GAL10-MLH1-VMA1-CBD, 2μ, TRP1, gift from T. Kunkel) and pEAE220, pEAE280, pEAE283, or pEAE290 was induced in galactose media (0.5-liter inductions yielding ∼2 g cell pellets) using methods described by Hall and Kunkel (2001). Cells were pelleted, washed with chitin buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA), repelleted, and resuspended in SDS–protein loading buffer. Samples were subjected to 8% SDS–PAGE and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with 4% milk overnight and probed with 12CA5 (αHA, Roche) antibody, followed by incubation with α-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch). Proteins were visualized by the ECL detection method (Amersham/GE). mlh3 proteins were expressed as described above for wild-type MLH3.

For chitin bead column chromatography, proteins were expressed (5-liter inductions yielding ∼17 g of induced cell pellet) from BJ2168 transformed with pMH1 and pEAE279, pEAE287, or pEAE291 as described above. After the chitin-buffer wash step, the cells were resuspended as a thick paste in a small volume of chitin buffer and frozen as drops in liquid nitrogen. The frozen cells were ground up with dry ice in a coffee grinder for lysis. After sublimation of the dry ice overnight at −20°, cells were thawed on ice and resuspended in 50 ml chitin buffer containing 1 mm PMSF. Chitin bead column chromatography was performed as described (Hall and Kunkel 2001). Briefly, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation and the supernatant was loaded onto a 2-ml chitin bead column equilibrated with chitin buffer. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of chitin buffer followed by 5 column volumes of ATP wash buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 200 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, 3 mm MgCl2, 1 mm PMSF, 400 μm ATP). Proteins were eluted with 3 column volumes of elution buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm PMSF, 50 mm DTT). After SDS–PAGE, protein samples were analyzed by Western blot analysis as described above.

RESULTS

mlh3 putative endonuclease domain point mutants show defects in spore viability similar to mlh3Δ:

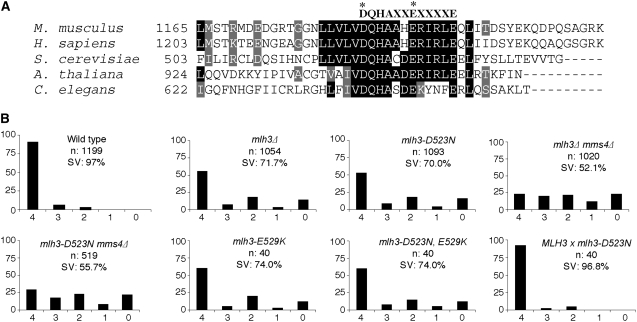

MLH3 homologs contain a highly conserved DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif in the C terminus (Figure 1A) that is thought to be a part of an endonuclease active site (Kadyrov et al. 2006). Mutations in this motif disrupted MutLα-dependent (MLH1-PMS1 in yeast, MLH1-PMS2 in humans) endonuclease activities and mismatch repair (Kadyrov et al. 2006, 2007; Erdeniz et al. 2007). To test whether this motif is important for MLH3 meiotic functions, we made single and double point mutations in MLH3 (D523N, E529K) that correspond to the human PMS2 and S. cerevisiae PMS1 endonuclease mutations (Kadyrov et al. 2006, 2007). The mutations in PMS2 and PMS1 did not affect their protein expression, the stability of the MutLα complex, or interactions between MutLα and MutSα (Kadyrov et al. 2006, 2007). The point mutations in MLH3 were introduced into the EAY1108/EAY1112 strain set (Argueso et al. 2004) and tested for their effect on spore viability. All three mlh3 endonuclease point mutations (mlh3-D523N, mlh3-E529K, and mlh3-D523N,E529K) conferred spore viability defects similar to mlh3Δ (Figure 1B). Diploid strains heterozygous for the mlh3-D523N, mlh3-E529K, and mlh3-D523N, E529K mutations showed spore viability similar to wild type, indicating that the mutations were recessive (Figure 1B; data not shown).

Figure 1.—

mlh3-endonuclease domain point mutants display an mlh3Δ-like phenotype with respect to meiotic spore viability. (A) Location of the conserved endonuclease motif DQHA(X)2E(X)4E in MLH3 homologs in Mus musculus (BC079861), Homo sapiens (NM_001040108), S. cerevisiae (MLH3), Arabidopsis thaliana (NM_119717) and Caenorhabditis elegans (H12C20.2). (B) The distribution of viable spores in the indicated mutants. The horizontal axis shows the viable-spore tetrad classes, and the vertical axis corresponds to the percentage of each class. The total number of tetrads dissected (n) and the percentage spore viability (SV) are shown for each mutant. Data for wild type are from Argueso et al. (2004).

The spore viability profile of the mlh3 mutants (excess of 4, 2, 0 spore viable tetrads over 3, 1) is consistent with high levels of MI nondisjunction (Ross-Macdonald and Roeder 1994; Hollingsworth et al. 1995; Hunter and Borts 1997; Argueso et al. 2003). The presence of centromere-linked markers at chromosome XV in the EAY1108/EAY1112 diploid allowed us to test two viable spore tetrads for phenotypes consistent with MI nondisjunction. A detection of a large percentage of sisters (Trp+/Ura−, Trp−/Ura+, or Trp+/Ura+) in this two-viable-spore class is suggestive of an MI defect (e.g., Khazanehdari and Borts 2000). Consistent with this, a high percentage of two-spore viable sister tetrads was seen in mlh3Δ (86%, n = 194 two-spore viable tetrads) and mlh3-D523N (88%, n = 198). These values were higher than seen in mlh1Δ (72%; Argueso et al. 2004). The lower level of sisters in mlh1Δ is likely due to random spore death resulting from the mlh1Δ mismatch repair defect.

The mlh3-D523N mutant shows mlh3Δ-like defects in meiotic crossing over:

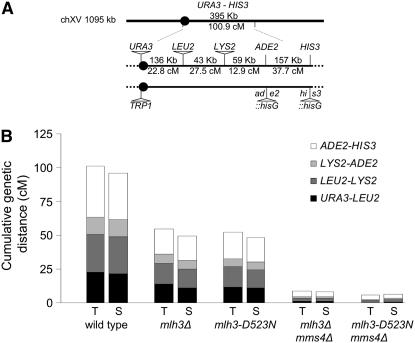

The mlh3-D523N mutation conferred an mlh3Δ-like phenotype for meiotic crossing over. We measured crossover frequency for mlh3-D523N in four consecutive genetic intervals on chromosome XV in complete tetrads in the EAY1108/EAY1112 strain background (Figure 2A). We found that, in all four intervals, crossing over in the mlh3-D523N mutant was similar to mlh3Δ. The sums of the genetic distances for the four intervals (URA3-HIS3) were 54.1 cM for mlh3-D523N, 56.2 cM for mlh3Δ, and 100.9 cM for wild type (Figure 2B, Table 1). These values did not change significantly when determined from single spores (50.2 cM for mlh3Δ, 49.7 cM for mlh3-D523N, 96.1 cM for wild-type strain). Previously, we observed that mlh1Δ mms4Δ mutants displayed a defect in meiotic crossing over that was much more severe than in the single mutants—13- to 15-fold reduced compared to wild type (Argueso et al. 2004). This observation was consistent with crossing over in S. cerevisiae occurring primarily through MSH4-MSH5/MLH1-MLH3- and MUS81-MMS4-dependent pathways (Argueso et al. 2004). As shown in Table 1 and Figure 2B, crossovers were reduced by 15- (single spores) to 17-fold (complete tetrads) in the mlh3-D523N mms4Δ mutant compared to wild type. A similar decrease in crossing over was observed in the mlh3Δ mms4Δ strains (12-fold in complete tetrads, 13-fold in single spores). Like mlh1Δ mms4Δ, high spore viability was seen in mlh3-D523N mms4Δ (56%, Figure 1) and mlh3Δ mms4Δ (52%), consistent with crossover-independent mechanisms for chromosome segregation (Argueso et al. 2004).

Figure 2.—

Cumulative genetic distances between the URA3 and HIS3 markers measured from complete tetrads (T) and single spores (S) in wild type, mlh3Δ, mlh3-D523N, mlh3Δ mms4Δ, and mlh3-D523N mms4Δ. (A) Location of genetic markers on chromosome XV. Physical and genetic distances between markers in the wild-type diploid are shown for each interval and the entire URA3-HIS3 interval. Solid circle indicates the centromere. (B) Cumulative genetic distance between the URA3 and HIS3 markers in wild type and the indicated mutant strains. Each bar is further divided into four sectors that correspond to the four genetic intervals that span URA3-HIS3 on chromosome XV. The size of the sectors is proportional to the contribution of each of the four intervals to the total URA3-HIS3 genetic distance. Wild-type data are from Argueso et al. (2004).

TABLE 1.

Genetic map distances and distribution of parental and recombinant progeny in wild-type, mlh3Δ, mlh3-D523N, mms4Δ, mlh3Δ mms4Δ, and mlh3-D523N mms4Δ strains

| Single spores

|

Tetrads

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | n | Parental single spores | Recombinant single spores | cM | 95% C.I. | n | PD | TT | NPD | cM | SE |

| URA3-LEU2 | |||||||||||

| Wild typea | 4644 | 3635 | 1009 | 21.7 | 20.6–23.0 | 1068 | 607 | 456 | 5 | 22.8 | 21.8–23.8 |

| mlh3Δ | 3023 | 2682 | 341 | 11.3 | 10.2–12.5 | 582 | 460 | 114 | 8 | 13.9 | 12.3–15.5 |

| mlh3-D523N | 3059 | 2727 | 332 | 10.9 | 9.8–12.0 | 575 | 455 | 117 | 3 | 11.7 | 10.5–12.9 |

| mms4Δa | 2732 | 2227 | 505 | 18.5 | 17.1–20.0 | 153 | 102 | 51 | 0 | 16.7 | 14.8–18.6 |

| mlh3Δ mms4Δ | 2127 | 2107 | 20 | 0.90 | 0.59–1.5 | 234 | 229 | 5 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.5 |

| mlh3-D523N mms4Δ | 1156 | 1153 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.07–0.82 | 152 | 152 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| LEU2-LYS2 | |||||||||||

| Wild typea | 4644 | 3388 | 1256 | 27.0 | 25.8–28.4 | 1068 | 496 | 569 | 3 | 27.5 | 26.6–28.4 |

| mlh3Δ | 3023 | 2610 | 413 | 13.7 | 12.5–15.0 | 582 | 424 | 154 | 4 | 15.3 | 13.9–16.6 |

| mlh3-D523N | 3059 | 2652 | 407 | 13.3 | 12.1–14.6 | 575 | 417 | 155 | 3 | 15.0 | 13.8–16.3 |

| mms4Δa | 2732 | 2081 | 651 | 23.8 | 22.3–25.5 | 153 | 77 | 75 | 1 | 26.5 | 23.8–29.2 |

| mlh3Δ mms4Δ | 2127 | 2073 | 54 | 2.5 | 1.9–3.3 | 234 | 223 | 11 | 0 | 2.4 | 1.7–3.0 |

| mlh3-D523N mms4Δ | 1156 | 1135 | 21 | 1.8 | 1.2–2.8 | 152 | 147 | 5 | 0 | 1.6 | 0.92–2.4 |

| LYS2-ADE2 | |||||||||||

| Wild typea | 4644 | 4052 | 592 | 12.7 | 11.8–13.8 | 1068 | 803 | 263 | 2 | 12.9 | 12.1–13.7 |

| mlh3Δ | 3023 | 2822 | 201 | 6.6 | 5.8–7.6 | 582 | 501 | 81 | 0 | 7 | 6.2–7.7 |

| mlh3-D523N | 3059 | 2880 | 179 | 5.9 | 5.0–6.8 | 575 | 512 | 62 | 1 | 5.9 | 5.1–6.7 |

| mms4Δa | 2732 | 2447 | 285 | 10.4 | 9.3–11.7 | 153 | 124 | 29 | 0 | 9.5 | 7.9–11.1 |

| mlh3Δ mms4Δ | 2127 | 2101 | 26 | 1.2 | 0.81–1.8 | 234 | 228 | 6 | 0 | 1.3 | 0.76–1.8 |

| mlh3-D523N mms4Δ | 1156 | 1142 | 14 | 1.2 | 0.69–2.0 | 152 | 149 | 3 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.43–1.5 |

| ADE2-HIS3 | |||||||||||

| Wild typea | 4644 | 3033 | 1611 | 34.7 | 33.3–36.1 | 1068 | 343 | 709 | 16 | 37.7 | 36.5–38.9 |

| mlh3Δ | 3023 | 2485 | 538 | 17.8 | 1.6–1.9 | 582 | 379 | 201 | 2 | 18.3 | 17.1–19.5 |

| mlh3-D523N | 3059 | 2512 | 547 | 17.9 | 1.6–1.9 | 575 | 373 | 197 | 5 | 19.7 | 18.3–21.2 |

| mms4Δa | 2732 | 1923 | 809 | 29.6 | 27.9–31.4 | 153 | 59 | 94 | 0 | 30.7 | 28.7–32.7 |

| mlh3Δ mms4Δ | 2127 | 2053 | 74 | 3.5 | 2.8–4.4 | 234 | 216 | 18 | 0 | 3.8 | 3.0–4.7 |

| mlh3-D523N mms4Δ | 1156 | 1119 | 37 | 3.2 | 2.3–4.4 | 152 | 142 | 10 | 0 | 3.3 | 2.3–4.3 |

| URA3-LYS2 | |||||||||||

| Wild typea | 4644 | 2815 | 1829 | 39.4 | 38.0–40.8 | 1068 | 264 | 759 | 45 | 48.2 | 46.5–49.9 |

| mlh3Δ | 3023 | 2359 | 664 | 22.0 | 20.5–23.5 | 582 | 333 | 240 | 9 | 25.3 | 23.5–27.0 |

| mlh3-D523N | 3059 | 2390 | 669 | 21.9 | 20.4–23.4 | 575 | 327 | 238 | 10 | 25.9 | 24.1–27.7 |

| mms4Δa | 2732 | 1764 | 968 | 35.4 | 33.6–37.3 | 153 | 49 | 98 | 6 | 43.8 | 39.2–48.4 |

| mlh3Δ mms4Δ | 2127 | 2059 | 68 | 3.2 | 2.5–4.0 | 234 | 219 | 15 | 0 | 3.2 | 2.4–4.0 |

| mlh3-D523N mms4Δ | 1156 | 1134 | 22 | 1.9 | 1.2–2.9 | 152 | 147 | 5 | 0 | 1.6 | 0.92–2.4 |

| LYS2-HIS3 | |||||||||||

| Wild typea | 4644 | 2829 | 1815 | 39.1 | 37.7–40.5 | 1068 | 278 | 744 | 46 | 47.8 | 46.0–49.6 |

| mlh3Δ | 3023 | 2360 | 663 | 21.9 | 20.5–23.5 | 582 | 333 | 240 | 9 | 25.3 | 23.5–27.0 |

| mlh3-D523N | 3059 | 2393 | 666 | 21.8 | 20.3–23.3 | 575 | 334 | 232 | 9 | 24.9 | 23.1–26.6 |

| mms4Δa | 2732 | 1806 | 926 | 33.9 | 32.1–35.7 | 153 | 53 | 98 | 2 | 35.9 | 32.8–39.0 |

| mlh3Δ mms4Δ | 2127 | 2029 | 98 | 4.6 | 3.8–5.6 | 234 | 210 | 24 | 0 | 5.1 | 4.1–6.1 |

| mlh3-D523N mms4Δ | 1156 | 1107 | 49 | 4.2 | 3.2–5.6 | 152 | 139 | 13 | 0 | 4.3 | 3.1–5.4 |

All mutants are isogenic derivatives of EAY1108/EAY1112 (materials and methods). For single spores, the recombination frequencies (number of recombinant spores/total spores) were multiplied by 100 to yield genetic map distances (in centimorgans); 95% confidence intervals for genetic map distance in the single spores were determined (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html). For tetrads, genetic distance in centimorgans (cM) was calculated using the formula of Perkins (1949): 50 × {TT + (6 × NPD)}/(PD + TT + NPD). For tetrad data, +/− 1 standard error around the genetic distance was calculated using the Stahl Laboratory Online Tools website (http://www.molbio.uoregon.edu/∼fstahl/). n, number of single spores or tetrads analyzed; PD, parental ditype; TT, tetratype; NPD, nonparental ditype.

Data are from Argueso et al. (2004).

mlh3Δ mutants show wild-type levels of meiotic gene conversion (Wang et al. 1999). The sum of conversion events at TRP1, URA3, LEU2, LYS2, ADE2, and HIS3 loci was 1.7% for wild type, 2.7% for mlh3-D523N, and 1.0% for mlh3Δ, with no postmeiotic segregation (PMS) events seen in the data set (data not shown; Argueso et al. 2004).

The mlh3-D523N mutant is defective in repair of frameshift mutation intermediates:

Flores-Rozas and Kolodner (1998) proposed that MLH1-MLH3 partially substitutes for MLH1-PMS1 to repair insertion/deletion mismatches recognized by MSH2-MSH3. Consistent with this, the mlh3Δ mutation conferred a modest elevation (13- to 21-fold) in the rate of reversion to Lys+ in strains containing 10-nucleotide insertions of mononucleotide repeats in the LYS2 gene (Harfe et al. 2000). We used the lys2∷InsE-A14 strain (Tran et al. 1997) to examine the contribution of the putative endonuclease activity of MLH3 in the repair of frameshift mutation intermediates. As shown in Table 2, the mlh3Δ mutant displayed a 6.3-fold higher mutation rate than wild type; a similar increase was seen for the mlh3-D523N mutant (7.9-fold). These results suggest that the putative endonuclease domain of MLH3 is required for this repair.

TABLE 2.

The mlh3Δ and mlh3-D523N mutations confer similar mutator phenotypes

| Genotype | n | Mutation rate (10−7), (95% C. I.) | Relative to wild type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 17 | 9.0 (6.8–17) | 1 |

| MLH3-KANMX | 16 | 8.3 (6.0–18) | 0.92 |

| mlh3Δ | 17 | 57 (41–114) | 6.3 |

| mlh3-D523N | 18 | 71 (42–130) | 7.9 |

The indicated derivatives of EAY1062 (SK1 wild type) were tested in the lys2∷insE-A14 mutator assay for reversion to Lys+. n, number of independent cultures tested.

The mlh3-D523N mutation does not affect protein stability or interaction with MLH1:

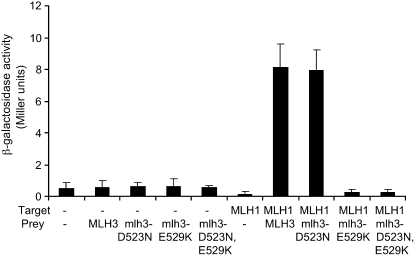

The mlh3 endonuclease point mutations were tested for their effect on MLH1-MLH3 interactions using the yeast two-hybrid assay. As shown in Figure 3, the interaction between MLH1 and mlh3-D523N was indistinguishable from wild type as measured using LacZ (Figure 3) and HIS3 (data not shown) reporters. We failed to detect two-hybrid interactions between MLH1 and mlh3-E529K and MLH1 and mlh3-D523N, -E529K.

Figure 3.—

Yeast two-hybrid analysis of mlh3 endonuclease domain point mutants with MLH1. Two-hybrid interactions between lexA-MLH1 (target) and GAL4-MLH3, GAL4-mlh3-D523N, GAL4-mlh3-E529K, and GAL4-mlh3-D523N, -E529K fusion constructs (prey) as measured in the ONPG assay for β-galactosidase activity. “-” indicates the presence of the empty target vector pBTM116 or the empty pGAD10 prey vector. Error bars indicate standard deviation from at least three independent assays. See materials and methods for details.

We examined the stability of wild-type and mutant MLH3 in Western blot analysis and during the purification of the MLH1-MLH3 complex. N-terminal HA-tagged versions of MLH3, mlh3-D523N, and mlh3-E529K were created and expressed from GAL10, URA3, and 2μ plasmids (materials and methods). HA-MLH3 and HA-mlh3-E529K were detected at similar levels by Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts probed with αHA antibody (Figure 4A). HA-mlh3-D523N appeared to be expressed at several-fold higher levels. The low signal of strains bearing these overexpression constructs suggests that it would be difficult to detect endogenous levels of HA-MLH3. To test whether mlh3-D523N copurifies with MLH1, we subjected the supernatant obtained from whole-cell extracts to chitin bead column chromatography. The strains used to make these extracts contain MLH3 plasmids that are present at extremely high copy numbers (2μ, leu2-d, ∼400 copies/cell). Because MLH1 is expressed as a chitin-binding domain fusion, this column will retain proteins that copurify with MLH1 (Hall and Kunkel 2001). MLH1 and associated proteins were then eluted from the column by activating cleavage of the chitin-binding domain from MLH1. Both HA-MLH3 (∼83 kDa) and HA-mlh3-D523N were found in the eluate when MLH1 (∼87 kDa) was co-overexpressed, whereas HA-mlh3-E529K was not detected, and HA-MLH3 was not detected in the absence of MLH1 coexpression (Figure 4B). These results are consistent with the D523N mutation not affecting the stability of MLH3 or the ability of MLH3 to interact with MLH1 and the mlh3-E529K mutation disrupting MLH1-MLH3 interactions. At present we have not determined if the band migrating in the Coomassie gel at ∼87 kDa is primarily MLH1 or contains stoichiometric amounts of MLH1 and MLH3.

mlh3-D523N confers a dominant-negative phenotype:

Shcherbakova and Kunkel (1999) showed that overexpression of MLH1 conferred a mutator phenotype that approached the mutator phenotype observed in mlh1Δ strains. As shown in Table 3, wild-type strains overexpressing MLH3 via the GAL10 promoter displayed a mutator phenotype in the lys2∷InsE-A14 reversion assay that was similar to that seen in strains overexpressing MLH1. The high mutator rate observed in MLH3 overexpression strains is consistent with increased levels of MLH1-MLH3 interfering with MMR, presumably by preventing MLH1-PMS1 from acting as the predominant MLH complex in MMR. Consistent with this is the finding that overexpression of a mutant MLH3 protein defective in MLH1-MLH3 interactions, mlh3-E529K, conferred a very weak dominant-negative phenotype. Strains overexpressing mlh3-D523N displayed an even higher mutator phenotype, relative to MLH3, that may be due to the higher protein expression consistently observed for mlh3-D523N compared to MLH3 (Figure 4A). The above information, combined with the protein expression and interaction data, suggests that MLH1-mlh3-D523N forms a stable complex that is defective for both MMR and meiotic functions.

DISCUSSION

We initiated this study to determine whether the putative endonuclease domain of MLH3 contributes to its meiotic functions. We found that the mlh3-D523N mutant was indistinguishable from mlh3Δ in vegetative mutator and meiotic spore viability and crossing-over assays and that the mlh3-D523N mutation conferred a dominant-negative phenotype in mutator assays. In addition, the mlh3-D523N mutant protein appeared stable and showed wild-type interactions with MLH1 as measured in two-hybrid and column chromatography assays. This information, in conjunction with the finding that the MLH3 endonuclease motif is highly conserved in eukaryotes, suggests that the MLH1-MLH3 complex possesses an endonuclease activity that is required for both mismatch repair and meiotic functions. Biochemical detection of such an activity will be required to confirm this hypothesis.

How might an MLH1-MLH3 endonuclease function contribute to both mismatch repair and meiotic functions? Biochemical studies showed that the MutLα endonuclease randomly nicks supercoiled DNA in the presence of ATP-Mn2+ (Kadyrov et al. 2006). During mismatch repair in vitro, the MutLα endonuclease activity was targeted to the discontinuous DNA strand and localized to DNA surrounding the mismatch site. This restriction of MutLα endonuclease activity required mismatch DNA, MutSα, and ATP-Mg2+ (Kadyrov et al. 2006). On the basis of this information we hypothesize that MSH2-MSH3 localizes MLH (MLH1-PMS1 or MLH1-MLH3) endonuclease activity during the repair of loop insertion/deletion mismatches. At present it is not clear in eukaryotes how meiotic crossover products form from Holliday junction intermediates. One possibility is that MLH3 endonuclease activity acts as a Holliday junction resolvase. Alternatively, such an activity could generate precursor recombination intermediates prior to crossover formation. In either model, it is attractive to propose that MSH4-MSH5 functions to restrict the MLH1-MLH3 endonuclease activity to recombination intermediates that are resolved to crossover products. Such an idea is supported by findings suggesting that MLH1-MLH3 acts downstream of MSH4-MSH5 (see Introduction) and that MSH4-MSH5 can bind Holliday junctions in vitro (Snowden et al. 2004). Further tests of the above models will require biochemical analyses of MSH4-MSH5 and MLH1-MLH3 activities on model recombination substrates.

In physical and genetic assays, Oh et al. (2007) and Jessop et al. (2006) showed that the reduction of crossovers observed in mlh3, msh4, and msh5 mutants could be suppressed by the sgs1-ΔC795 mutation. These studies suggest that SGS1 antagonizes the pro-crossover functions of MSH4-MSH5 and MLH1-MLH3. On the basis of these observations, we would not have expected to see suppression of the mlh3Δ crossover defect by the sgs1-ΔC795 mutation if MLH1-MLH3 acted as the sole junction resolvase during meiosis. If MLH1-MLH3 is indeed a resolvase, then one way to explain this dilemma is that resolvase activity is functionally redundant in S. cerevisiae and MMS4-MUS81 acts in the absence of MLH1-MLH3. Such an idea is supported by the finding that crossing over is severely decreased in mlh1Δ mms4Δ and mlh3Δ mms4Δ mutants (Figure 2B; Argueso et al. 2004). Unfortunately, it is not possible to test this directly by examining the sgs1-ΔC795 mlh3Δ mms4Δ triple mutant because sgs1Δ mms4Δ double mutants are inviable (Mullen et al. 2001). It will be informative to examine recombination intermediates by two-dimensional electrophoresis in mlh3Δ, mlh3-D523N, and mms4Δ mlh3-D523N to determine if dHJs accumulate in the mms4Δ mlh3-D523N double mutant as predicted above.

On the basis of mutational analysis of the PMS1 endonuclease domain, we were surprised that the mlh3-E529K mutation disrupted the interaction between MLH1 and MLH3 in chromatography and two-hybrid assays. These results suggest that there is an overlap between the MLH3 putative endonuclease domain and residues required for interaction with MLH1 that was not seen for the yeast and human MutLα complexes. Such an observation is of interest because MLH3 foci were shown to associate with chromosomes prior to MLH1 in mouse spermatocytes, suggesting that MLH1-MLH3 interactions are dynamic (Lipkin et al. 2002; Kolas et al. 2005). Studies aimed at understanding this interaction are ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Alani laboratory, Paula Cohen, Neil Hunter, and Tom Kunkel for thoughtful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM53085 (E.A. and K.T.N.) and a State University of New York fellowship (A.J.P.).

References

- Abraham, J., B. Lemmers, M. P. Hande, M. E. Moynahan, C. Chahwan et al., 2003. Eme1 is involved in DNA damage processing and maintenance of genomic stability in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 22 6137–6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argueso, J. L., A. W. Kijas, S. Sarin, J. Heck, M. Waase et al., 2003. Systematic mutagenesis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH1 gene reveals distinct roles for Mlh1p in meiotic crossing over and in vegetative and meiotic mismatch repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 873–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argueso, J. L., J. Wanat, Z. Gemici and E. Alani, 2004. Competing crossover pathways act during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 168 1805–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S. M., A. W. Plug, T.A. Prolla, C. E. Bronner, A. C. Harris et al., 1996. Involvement of mouse Mlh1 in DNA mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over. Nat. Genet. 3 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, A. L., and M. A. Hultén, 1998. Crossing over analysis at pachytene in man. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 6 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, M. N., P. H. Gaillard, W. H. McDonald, P. Shanahan, J. R. Yates, III et al., 2001. Mus81-Eme1 are essential components of a Holliday junction resolvase. Cell 107 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia, A., A. Constantinou and S. C. West, 2003. Identification and characterization of the human mus81-eme1 endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 278 25172–25178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De los Santos, T., N. Hunter, C. Lee, B. Larkin, J. Loidl et al., 2003. The Mus81/Mms4 endonuclease acts independently of double-Holliday junction resolution to promote a distinct subset of crossovers during meiosis in budding yeast. Genetics 164 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes, S. M., G. Tomer, M. Nguyen, N. Erdeniz, N. C. Juba et al., 2007. The E705K mutation in hPMS2 exerts recessive, not dominant, effects on mismatch repair. Cancer Lett. 249 148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdeniz, N., M. Nguyen, S. M. Deschênes and R. M. Liskay, 2007. Mutations affecting a putative MutLalpha endonuclease motif impact multiple mismatch repair functions. DNA Rep. 6 1463–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Rozas, H., and R. D. Kolodner, 1998. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH3 gene functions in MSH3-dependent suppression of frameshift mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 12404–12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell, L. J., F. Osman, R. J. Gilbert and M. C. Whitby, 2007. Mus81 cleavage of Holliday junctions: A failsafe for processing meiotic recombination intermediates? EMBO J. 26 1891–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, R. D., R. H. Schiestl, A. R. Willems and R. A. Woods, 1995. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast 11 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker, 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15 1541–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M. C., and T. A. Kunkel, 2001. Purification of eukaryotic MutL homologs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae using self-affinity technology. Protein Expr. Purif. 21 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe, B. D., B. K. Minesinger and S. Jinks-Robertson, 2000. Discrete in vivo roles for the MutL homologs Mlh2p and Mlh3p in the removal of frameshift intermediates in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 10 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck, J. A., J. L. Argueso, Z. Gemici, R. G. Reeves, A. Bernard et al., 2006. Negative epistasis between natural variants of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MLH1 and PMS1 genes results in a defect in mismatch repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 3256–3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, E. R., and R. H. Borts, 2004. Meiotic recombination intermediates and mismatch repair proteins. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 107 232–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth, N. M., and S. J. Brill, 2004. The Mus81 solution to resolution: generating meiotic crossovers without Holliday junctions. Genes Dev. 18 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth, N. M., L. Ponte and C. Halsey, 1995. MSH5, a novel MutS homolog, facilitates meiotic reciprocal recombination between homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae but not mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 9 1728–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, N., and R. H. Borts, 1997. Mlh1 is unique among mismatch repair proteins in its ability to promote crossing-over during meiosis. Genes Dev. 11 1573–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, L., B. Rockmill, G. S. Roeder and M. Lichten, 2006. Meiotic chromosome synapsis-promoting proteins antagonize the anti-crossover activity of sgs1. PLoS Genet. 2 e155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G. H., 1987. Chiasmata, pp. 213–238 in Meiosis, edited by P. Moens. Academic Press, New York/London/San Diego.

- Kaback, D. B., D. Barber, J. Mahon, J. Lamb and J. You, 1999. Chromosome size-dependent control of meiotic reciprocal recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the role of crossover interference. Genetics 152 1475–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrov, F. A., L. Dzantiev, N. Constantin and P. Modrich, 2006. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell 126 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrov, F. A., S. F. Holmes, M. E. Arana, O. A. Lukianova, M. O'Donnell et al., 2007. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLa is a mismatch repair endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 282 37181–37190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazanehdari, K. A., and R. H. Borts, 2000. EXO1 and MSH4 differentially affect crossing-over and segregation. Chromosoma 109 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolas, N. K., A. Svetlanov, M. L. Lenzi, F. P. Macaluso, S. M. Lipkin et al., 2005. Localization of MMR proteins on meiotic chromosomes in mice indicates distinct functions during prophase I. J. Cell Biol. 171 447–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin, S. M., P. B. Moens, V. Wang, M. Lenzi, D. Shanmugarajah et al., 2002. Meiotic arrest and aneuploidy in MLH3-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 31 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M. P., 1974. The need for a chiasma binder. J. Theor. Biol. 48 485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens, P. B., N. K. Kolas, M. Tarsounas, E. Marcon, P. E. Cohen et al., 2002. The time course and chromosomal localization of recombination-related proteins at meiosis in the mouse are compatible with models that can resolve the early DNA-DNA interactions without reciprocal recombination. J. Cell Sci. 115 1611–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, R., and S. Fogel, 1974. Genetical interference and gene conversion, pp. 263–275 in Mechanisms in Recombination, edited by R. Grell. Plenum Press, New York.

- Mullen, J. R., V. Kaliraman, S. S. Ibrahim and S. J. Brill, 2001. Requirement for three novel protein complexes in the absence of the Sgs1 DNA helicase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 157 103–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S. D., J. P. Lao, P. Y. Hwang, A. F. Taylor, G. R. Smith et al., 2007. BLM ortholog, Sgs1, prevents aberrant crossing-over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell 130 259–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Q., T. A. Prolla and R. M. Liskay, 1997. Functional domains of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mlh1p and Pms1p DNA mismatch repair proteins and their relevance to human hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer-associated mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 4465–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, D. D., 1949. Biochemical mutants in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Genetics 34 607–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., F. Winston and P. Hieter, 1990. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Ross-Macdonald, P., and G. S. Roeder, 1994. Mutation of a meiosis-specific MutS homolog decreases crossing over but not mismatch correction. Cell 79 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santucci-Darmanin, S., S. Neyton, F. Lespinasse, A. Saunières, P. Gaudray et al., 2002. The DNA mismatch-repair MLH3 protein interacts with MSH4 in meiotic cells, supporting a role for this MutL homolog in mammalian meiotic recombination. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 1697–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakova, P. V., and T. A. Kunkel, 1999. Mutator phenotypes conferred by MLH1 overexpression and by heterozygosity for mlh1 mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 3177–3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, M., K. Sakai, A. Shinohara and D. K. Bishop, 2003. Crossover interference in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a TID1/RDH54- and DMC1-dependent pathway. Genetics 163 1273–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, T., S. Acharya, C. Butz, M. Berardini and R. Fishel, 2004. hMSH4-hMSH5 recognizes Holliday junctions and forms a meiosis-specific sliding clamp that embraces homologous chromosomes. Mol. Cell 15 437–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi, A., S. Tesse, S. Gargano, F. James, N. Kleckner et al., 2003. Meiotic double-strand breaks at the interface of chromosome movement, chromosome remodeling, and reductional division. Genes Dev. 17 2675–2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H. T., J. D. Keen, M. Kricker, M. A. Resnick and D. A. Gordenin, 1997. Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 2859–2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann and P. Philippsen, 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. F., N. Kleckner and N. Hunter, 1999. Functional specificity of MutL homologs in yeast: evidence for three Mlh1-based heterocomplexes with distinct roles during meiosis in recombination and mismatch correction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 13914–13919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitby, M. C., 2005. Making crossovers during meiosis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33 1451–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, L. M., C. A. Hodges, E. Baart, S. M. Baker, M. Liskay et al., 1999. Chromosomal influence on meiotic spindle assembly: abnormal meiosis I in female Mlh1 mutant mice. J. Cell Biol. 145 1395–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H. G., and D. Koshland, 2005. Chromosome morphogenesis: condensin-dependent cohesin removal during meiosis. Cell 123 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]