Abstract

Understanding how neurons adopt particular fates is a fundamental challenge in developmental neurobiology. To address this issue, we have been studying a Caenorhabditis elegans lineage that produces the HSN motor neuron and the PHB sensory neuron, sister cells produced by the HSN/PHB precursor. We have previously shown that the novel protein HAM-1 controls the asymmetric neuroblast division in this lineage. In this study we examine tbx-2 and egl-5, genes that act in concert with ham-1 to regulate HSN and PHB fate. In screens for mutants with abnormal HSN development, we identified the T-box protein TBX-2 as being important for both HSN and PHB differentiation. TBX-2, along with HAM-1, regulates the migrations of the HSNs and prevents the PHB neurons from adopting an apoptotic fate. The homeobox gene egl-5 has been shown to regulate the migration and later differentiation of the HSN. While mutations that disrupt its function show no obvious role for EGL-5 in PHB development, loss of egl-5 in a ham-1 mutant background leads to PHB differentiation defects. Expression of EGL-5 in the HSN/PHB precursor but not in the PHB neuron suggests that EGL-5 specifies precursor fate. These observations reveal a role for both EGL-5 and TBX-2 in neural fate specification in the HSN/PHB lineage.

DEVELOPMENT relies on the intricate interplay between cell death, proliferation, migration, and differentiation to assure that proper numbers of cells are generated. The number of mitotic cells produced during development, for example, is balanced by both apoptosis and terminal differentiation. Asymmetric cell divisions have been shown to play an essential role in generating cells at the right time and place during animal development.

Several types of molecules have been implicated in the regulation of asymmetric cell divisions. Cell determinants such as Numb and Prospero are segregated to one daughter cell, causing it to adopt a particular fate (Uemura et al. 1989; Rhyu et al. 1994; Hirata et al. 1995; Knoblich et al. 1995; Rhyu and Knoblich 1995; Spana et al. 1995). Other molecules like Miranda regulate the distribution of the determinants (Ikeshima-Kataoka et al. 1997), and molecules like Inscutable control both the distribution of molecules like Miranda and orient the spindle so that determinants are inherited by a single daughter cell (Kraut and Campos-Ortega 1996; Kraut et al. 1996; Shen et al. 1997).

While much is known about the intrinsic molecules that control the asymmetric divisions of neuroblasts in Drosophila and of the Caenorhabditis elegans zygote, much less is known about how neuroblasts in C. elegans divide asymmetrically. Only two molecules, HAM-1 and PIG-1, are known to control both the sizes of daughter cells, presumably by controlling spindle position, and daughter cell fate of neuroblast divisions (Guenther and Garriga 1996; Frank et al. 2005; Cordes et al. 2006). One interesting feature of these molecules is that they function only in neuroblast lineages that produce apoptotic cells, such as the HSN/PHB lineage (Figure 1A). Mutations in these genes lead to the transformation of the cells fated to die into their sister cells, either neurons or neuronal precursors, leading to the production of extra neurons. A working model proposes that HAM-1 distributes developmental potential in the form of cell-fate determinants to the daughter cell that normally survives (Frank et al. 2005). If this model is correct, loss of these determinants should result in the loss of neurons in the affected divisions.

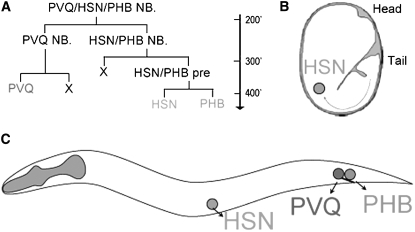

Figure 1.—

HSN and PHB neuron development. (A) PVQ/HSN/PHB neuronal lineage. Vertical arrow represents time of development in minutes at 20°, beginning with the first embryonic cleavage at 0 min. NB stands for neuroblast and pre stands for precursor. (B) Schematic of an embryo showing the migration route of the HSN. Both the HSN and PHB are born in the tail of the developing embryo at about the stage shown in this diagram. (C) Schematic showing the positions of the HSN motor neuron, the chemosensory phasmid neuron PHB, and the interneuron PVQ in a newly hatched L1 hermaphrodite. Anterior is to the left, dorsal is up.

In this article, we describe two genes that are required for the production of the HSN and PHB neurons. In a screen for mutations that disrupt HSN development, we identified a mutant allele of tbx-2, which encodes a T-box protein of the TBX-2/3/4/5 family. T-box proteins have been shown to regulate cell-fate specification in multiple tissues (Naiche et al. 2005). We provide evidence suggesting that TBX-2 acts as a repressor of apoptosis for the PHB neuron. We also describe a new role for the Hox gene egl-5 in the HSN/PHB lineage. Both tbx-2 and egl-5 regulate the specification of HSNs and PHBs, and aspects of this regulation are revealed only in a ham-1 mutant background. While our genetic observations are consistent with a role of TBX-2 and EGL-5 as determinants that regulate HSN and PHB development, we provide genetic evidence that suggests that these molecules may not be directly distributed by HAM-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General procedure and strains:

Strains were grown at 20° and maintained as described (Brenner 1974). In addition to the wild-type strain N2, strains containing the following mutations and transgenes were used in this work:

LGI: dpy-5(e61) (Brenner 1974) kyIs39 [Psra-6∷gfp] (Troemel et al. 1995); ynIs45 [Pflp-15∷gfp] (Li et al. 1999; Kim and Li 2004); zdIs5[mec-4∷gfp] (Clark and Chiu 2003).

LGII: bli-2(e768) (Brenner 1974); gmIs20 [hlh-14∷gfp] (Frank et al. 2003); gmIs13 [Psrb-6∷gfp] (this study).

LGIII: dpy-17(e164) (Brenner 1974); tbx-2(ok529) (Gene Knockout Consortium, http://celeganskoconsortium.omrf.org/); tbx-2(gm111) (this study); egl-5(n945) (Trent et al. 1983); unc-32(e189) (Brenner 1974); gm345 (this study) dpy-18(e364) (Brenner 1974).

LGIV: dpy-11(e224) (Brenner 1974); ham-1(n1438) (Desai et al. 1988); ham-1(gm279) (Frank et al. 2005); kyIs179 [Punc-86∷gfp] (Gitai et al. 2003).

LGV: unc-5(e53) (Brenner 1974); gmIs22 [Pnlp-1∷gfp] (Li et al. 1999; Frank et al. 2003); muIs13[egl-5∷lacZ] (Wang et al. 1993).

LGX: lon-2(e678) (Brenner 1974).

Rearrangements: +/qC1[dpy-19(e1259) glp-1(q339)] III (Graham and Kimble 1993); +/mT1 II; +/mT1[dpy-10(e128)] III (M. Edgley, personal communication).

Unmapped transgene: AW0095 [tbx-2∷gfp] (A. Woollard, personal communication).

Isolation and mapping of the tbx-2(gm111) and gm345 mutations:

In a screen for mutations that disrupt HSN development, we mutagenized wild-type P0 hermaphrodites with 50 mm EMS for 4 hr and transferred individual F1 hermaphrodite progeny to separate Petri plates. We then examined 15–20 F2 progeny of individual F1's for HSN defects using Nomarski optics. One F1 segregated arrested first larval stage (L1) progeny that lacked detectable HSNs by Nomarski optics. These animals also had either a “Pharynx unattached” (Pun) phenotype or the pharynx was thin and abnormal in appearance.

We crossed wild-type males to hermaphrodites that segregated the L1 arrested phenotype. F1 males were crossed to two strains, MT465 [dpy-5; bli-2; unc-32] and MT464 [unc-5; dpy-11; lon-2], and 10 F2 L4 hermaphrodite cross progeny were isolated from each cross. For each cross, we chose an F2 hermaphrodite that segregated L1 arrested animals and transferred 20 of its wild-type F3 progeny to individual plates (the progeny were not Dpy, Bli, or Unc for the MT465 cross and were not Unc, Dpy, or Lon for the MT464 cross). For the MT464 cross, approximately two-thirds of the F3 progeny segregated animals that displayed the L1 arrest, Unc, Dpy, or Lon phenotypes. For the MT465 cross, approximately two-thirds of the progeny segregated the Dpy and Bli phenotypes, but all 20 segregated the L1 arrest and Unc phenotype suggesting that the mutation causing the L1 arrest is linked to unc-32. The mutation responsible for this phenotype was named gm111 and balanced by the qC1 balancer chromosome.

We also generated gm111/qC1 strains that contained a gmIs13(srb-6∷gfp) transgene and noted that one of the phasmid neurons, which we later showed to be PHB, was missing ∼91% of the time in gm111 homozygous animals. This transgene was used in additional mapping experiments.

In a subsequent mapping experiment, we set out to order gm111 relative to dpy-17 and unc-32 by building the strain gmIs13/+; dpy-17 + unc-32/+ gm111 + and isolating Unc, non-Dpy, and Dpy, non-Unc self progeny. All 15 of the Unc, non-Dpy progeny segregated L1 arrested animals. We were surprised to find that we could detect the HSNs in these arrested hermaphrodites, although the neurons were often misplaced. We also noted that while those strains that retained the gmIs13 transgene were occasionally missing phasmid neurons, the penetrance of this defect was much higher in the original strain. We conclude that in these recombinant hermaphrodites we crossed off a linked modifier that enhanced the HSN and PHB defects caused by gm111.

Of the 20 Dpy non-Unc progeny, 3 were sterile. The remaining fertile hermaphrodites segregated dead embryos, arrested larvae and sterile as well as fertile adults. The arrested larvae and sterile adult progeny from each of the Dpy, non-Unc recombinant animals often had HSN migration defects and those that retained gmIs13 in the background often had missing phasmid neurons. As with the arrested larvae from the Unc, non-Dpy recombinants, the penetrance of the phasmid neuron defect was higher in the original strain. Arrested L1 larvae were often Pun. From one of the Dpy, non-Unc recombinant progeny that contained gmIs13, we cloned 20 Dpy non-Unc fertile progeny, and they all segregated Dpy, Unc progeny, suggesting that when homozygous the recombinant chromosome resulted in the lethal and sterile phenotypes described above. Taken together, the mapping experiments suggest that the original strain contained two mutations: gm111, which mapped near or to the left of dpy-17, and a second mutation, which we named gm345, which maps near or to the right of unc-32. Alone, each mutation caused partially penetrant HSN and PHB phenotypes that were enhanced in the double mutant. The gm111 unc-32 and dpy-17 gm345 recombinant chromosomes were balanced over a qC1 chromosome. Like the original double-mutant strain, gm111 animals retained the Pun/abnormal pharynx phenotype.

To confirm our hypothesis that these two mutations caused the severe HSN defects, we crossed gm111 gm345/qC1 males to +ina-1 dpy-18/unc-32 +dpy-18 hermaphrodites and transferred individual non-Dpy progeny to separate plates. From F1's that segregated both the unc-32 dpy-18 and the gm111 gm345 chromosomes, we transferred 13 individual Dpy, non-Unc and six Unc Non-Dpy F2 recombinant progeny to separate plates. All of the Dpy, non-Unc progeny segregated L1 arrested animals with misplaced HSNs, phenotypes associated with the gm111 mutation. None of the Unc non-Dpy hermaphrodites segregated dead eggs, arrested larvae, or sterile adults. From these and the previous mapping experiments, we conclude that gm345 maps near unc-32.

Our phenotypic analysis of gm345 was conducted using a dpy-17 gm345 recombinant chromosome that was isolated as described above. These mutant animals arrest at various stages of development, and those that make it to adulthood are sterile. Arrested L1 animals can display a Pun phenotype. Adult hermaphrodites can be vulvaless and less frequently multivulval. They also display HSN migration and PHB defects (data not shown). Presumably the dpy-17 mutation does not contribute to the gm345 mutant phenotypes. gm345 is not considered further in this article.

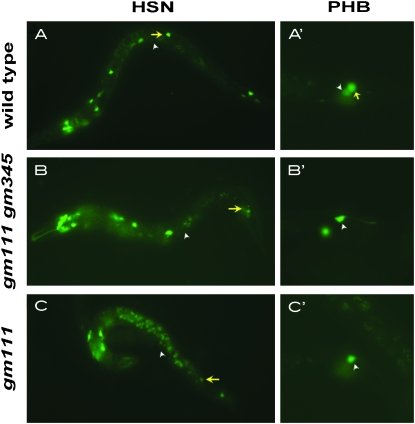

Using the transgenic marker gmIs13 (Psrb-6∷gfp) to detect the PHA and PHB neurons, we found that 91% of the sides scored in the gm111 gm345 animals had a single neuron that expressed GFP in arrested L1 hermaphrodites (Figure 2, A′–C′). Normally, each side of a gmIs13 animal has two GFP-expressing cells in the tail, one PHB and one PHA, a second phasmid neuron that is unrelated linearly to the HSN. On the basis of the HSN phenotype and further analysis described below, we speculate that the arrested animals lacked PHBs.

Figure 2.—

HSN and PHB phenotypes in tbx-2 and tbx-2 gm345 hermaphrodites. The reporters kyIs179 and gmIs13 express GFP in the HSN (A–C) and the PHB (A′–C′), respectively. (A) kyIs179; (B) gm111 gm345; kyIs179; and (C) gm111; kyIs179. Anterior is to the left, dorsal is up. Arrows point to the HSN, and the arrowheads indicate the position of the center of the gonad primordium. In wild-type animals, the HSN lies lateral to the gonad and is displaced posteriorly along its migratory route in the two mutant backgrounds. (A′) gmIs13; (B′) gmIs13; gm111 gm345; and (C′) gmIs13; tbx-2(gm111). Arrows point to the PHB, and the arrowheads point to the PHA. There is one PHA and one PHB on each side in wild-type animals and hence two GFP+ cells are seen on each side of the animal. Mutants are sometimes missing a PHB and in these cases have only one GFP+ cell, the PHA, on that side of the animal.

hlh-14 mutants lack HSNs, PHBs, and PVQ interneurons because the fate of the neuroblast that produces these cells is altered (Frank et al. 2003). To test whether the gm111 gm345 L1 arrested animals also lacked PVQ neurons, we analyzed these mutant animals using the kyIs39 (sra-6∷gfp) transgene marker (Troemel et al. 1995). Unlike hlh-14 mutants, the arrested gm111 gm345 L1 animals produced normal numbers of PVQs (data not shown). This observation suggests that the neuroblast that produces all three neurons is normal in these mutants.

Complementation tests:

We noted that the tbx-2(ok529) mutation, which lies just to the right of dpy-17, caused an L1 arrest phenotype similar to that produced by the gm111 mutation. Analysis of the HSN and phasmid neuron phenotypes of tbx-2(ok529) were also similar, increasing the likelihood that gm111 is a tbx-2 allele. To test this hypothesis, we crossed males heterozygous for the kyIs179 HSN reporter into tbx-2(ok529)/mT1 hermaphrodites. F1 males carrying the reporter were crossed to gm111 unc-32/qC1 hermaphrodites, and we scored cross progeny that contained the kyIs179 transgene for the L1 arrest and HSN migration phenotypes of tbx-2 mutants. Because this transgene often segregates away from the X chromosome, most of the progeny that contained the transgene were male and hence lacked HSNs. Of the 44 progeny scored, 29 had abnormal pharynxes similar to those seen in ok529 and gm111 animals. The frequency of animals with this defect was higher than one would expect and probably resulted from the bias introduced by picking L1 animals for the analysis by Nomarski and fluorescence microscopy. Because the mutant L1 animals arrest at this stage, with time these L1 mutants accumulate on the plate. Only 15 of the 44 animals were hermaphrodites: 11 of these had at least one HSN that was displaced. We concluded that gm111 and ok529 failed to complement and that gm111 is a tbx-2 allele.

Strain constructions:

ced-4 tbx-2; gmIs13:

tbx-2 and ced-4 are 0.31 MU apart on LGIII. zdIs5/+; ced-4 dpy-17 unc-36/+++ males were crossed to tbx-2(ok529)/qC1 hermaphrodites. Approximately 1000 F2 cross progeny were picked from cross progeny plates that were of the genotype zdIs5/+; ced-4 dpy-17+ unc-36/++ tbx-2(ok529)+. Individual non-Unc, non-Dpy F3 hermaphrodites with extra PLM neurons (26% of ced-4 mutant animals have extra PLM neurons) were transferred to separate plates. The presence of tbx-2(ok529) in the next generation was verified by its Pun phenotype. We then constructed a strain containing gmIs13 and the recombinant ced-4 tbx-2 chromosome balanced by qC1 using standard genetic techniques.

tbx-2 egl-5; gmIs13:

tbx-2 and egl-5 are 1.51 MU apart on LGIII. Heterozygous dpy-17 egl-5 males were crossed into tbx-2(ok529)/qC1 hermaphrodites, and ∼60 individual F1 progeny were transferred to separate plates. Hermaphrodites that segregated dpy-17 egl-5 and tbx-2(ok529) were screened for non-Dpy Egl animals. The recombinant tbx-2(ok529) egl-5(n945) chromosome was balanced over qC1 and subsequently crossed into gmIs13.

Embryo fixation and staining:

Embryos were fixed and stained as described (Guenther and Garriga 1996). Primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP at 1:1000 dilution (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), mouse monoclonal anti-β-galactosidase at 1:500 dilution (Promega, Madison, WI) and mouse anti-EGL-43 at 1:2 dilution (Guenther and Garriga 1996). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa-488 goat antirabbit IgG, Alexa-568 goat antimouse, and Alexa-568 donkey antimouse (Molecular Probes), all at 1:100 dilution.

Imaging and scoring was done on a Zeiss Axioskop2 fluorescence compound microscope. Images were taken using an ORCA-ER CCD camera (Hammamatsu) and Openlab v.3.1 Imaging software (Improvision), and manipulated using Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS

tbx-2 mutations:

The HSNs are a pair of bilaterally symmetric serotonergic motor neurons that innervate the vulval muscles and stimulate hermaphrodites to lay eggs (White et al. 1986; Desai et al. 1988). The HSNs are generated in the tail of the embryo by two HSN/PHB precursors that each divide to generate an HSN and a PHB phasmid chemosensory neuron (Figure 1, A and C). Shortly after being born, the HSNs of hermaphrodites migrate anteriorly to positions near the center of the embryo flanking the gonad primordium (Figure 1, B and C). In males, the HSNs die during this migration (Sulston et al. 1983). In hermaphrodites, the HSNs differentiate into serotonergic motor neurons during larval and adult stages (Desai et al. 1988). Using Nomarski optics, HSNs can be identified in their final positions in newly hatched L1 hermaphrodites. Mutants with defects in HSN development can often be identified as L1 animals with missing or misplaced HSNs (Desai et al. 1988).

To identify genes involved in HSN development, we used EMS mutagenesis and Nomarski microscopy in an F1 clonal screen for HSN defects and identified an F1 animal that segregated arrested L1 hermaphrodites that lacked any obvious HSNs. This phenotype can be caused by a failure to produce HSNs (Frank et al. 2003) or by the death of the HSNs (Desai et al. 1988), their fate in males. Alternatively, the HSNs can be produced, but then fail to migrate (Desai et al. 1988). When the HSNs fail to migrate from their birthplace in the tail, we cannot distinguish them from other neurons in the lumbar ganglion using Nomarski optics.

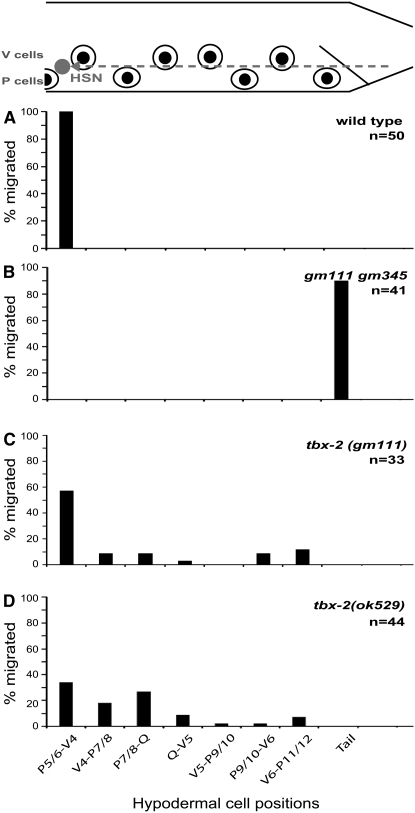

The L1 arrest and HSN phenotypes mapped to linkage group III. Three factor mapping of the mutant chromosome separated two linked mutations, gm111 and gm345, that together contributed to the HSN and PHB phenotypes (Figures 2 and 3 and materials and methods). The gm111 mutation mapped near or to the left of dpy-17 and caused the L1 arrest phenotype. In this article, we focus on the gm111 mutation, and information on gm345 is presented in materials and methods. The arrested L1 gm111 hermaphrodites had HSNs that could be detected by Nomarski optics, but they often arrested their migration prematurely and were displaced posteriorly (Figure 2, A–C, and Figure 3). Using the kyIs179(Punc-86∷gfp) transgene as an HSN marker (Gitai et al. 2003), both the normally positioned and misplaced neurons expressed GFP, confirming that the ectopic neurons identified by Nomarski optics were HSNs (Figure 2).

Figure 3.—

tbx-2 mutants have HSN migration defects. At the top is a schematic diagram of the posterior half of an L1 hermaphrodite. Anterior is to the left, dorsal is up. The dotted line represents the migratory route of the HSN. The positions of the V- and P-hypodermal cell nuclei are represented by eye-shaped structures, starting with P5/6 at the anteriormost position. The tick marks along each graph mark the position of the corresponding hypodermal cell aligned with respect to the diagram to the top. The y-axes of the graphs represent the percentage of neurons at each position along the anterior–posterior axis. n is the number of HSNs scored. All strains were scored with the reporter kyIs179. (A) Wild type, (B) tbx-2(gm111) gm345, (C) tbx-2(gm111), and (D) tbx-2(ok529).

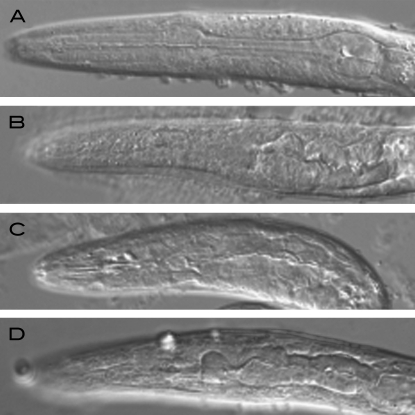

The gene tbx-2 maps just to the right of dpy-17, and mutations in this gene cause an L1 arrest and pharyngeal phenotypes that were similar to those exhibited by gm111 animals (Roy Chowdhuri et al. 2006). Both gm111 and the tbx-2 mutation caused an L1 arrest phenotype that results from the inability of the animals to feed: the pharynx was often detached from the mouth (Pun phenotype), and those pharynxes that were attached were thin and abnormally shaped (Figure 4). We also found that gm111 and tbx-2(ok529) mutants have similar HSN and PHB defects.

Figure 4.—

Nomarski optic images of wild-type and mutant pharynxes. (A) Wild type, (B) gm111 gm345, (C) tbx-2(gm111), and (D) tbx-2(ok529). Anterior is to the left.

We assayed the PHB neurons in gm111 and tbx-2(ok529) L1 arrested hermaphrodites using two different GFP markers: gmIs13, which expresses GFP in PHAs and PHBs (Frank et al. 2003), and gmIs22(nlp-1∷GFP), which expresses GFP in the PHBs but not the PHAs (Li et al. 1999; Frank et al. 2003). In both of these reporter backgrounds, tbx-2(gm111) and tbx-2(ok529) arrested animals had sides with missing cells (Figures 2C′ and 5A) suggesting that the mutation specifically affected PHB. Consistent with this interpretation, the PHA marker ynIs45 (flp-15∷GFP) revealed that the tbx-2 mutants were not missing PHAs (Li et al. 1999; Kim and Li 2004) (data not shown).

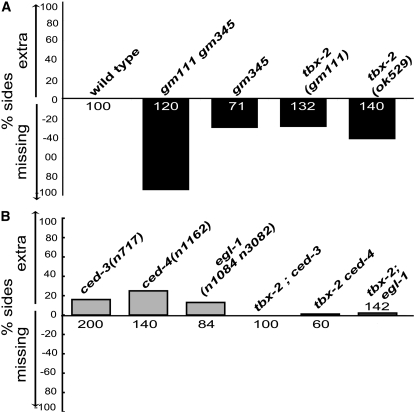

Figure 5.—

PHB defects in tbx-2(gm111) gm345, tbx-2(gm111), and tbx-2(ok529) mutants and their suppression by mutations in cell-death genes. The GFP reporter gmIs13 was used to quantify the number of phasmid neurons. Y-axis denotes the percentage of sides scored with either an extra or a missing phasmid neuron. The number of sides scored are noted on the bars for each genotype. Genotypes are as indicated. (A) tbx-2 mutants are missing phasmid neurons. (B) The missing cell phenotype of tbx-2 mutants is rescued by mutations in genes that promote cell death. Double mutants using ced-3, ced-4, or egl-1 were all built with tbx-2(ok529).

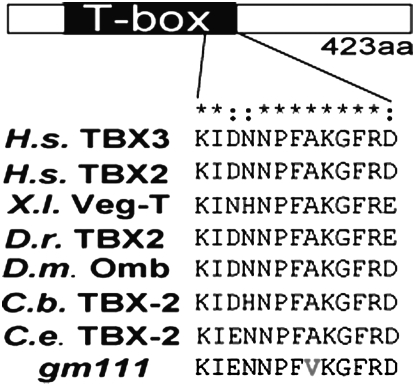

Complementation tests and sequencing confirmed that gm111 is a tbx-2 allele (materials and methods). The gm111 mutation is predicted to result in an Ala238Val change in the TBX-2 protein (Figure 6). Although this change is conservative, we speculate that it affects the ability of the protein to bind target DNA. The 10-amino-acid sequence flanking this Ala has been conserved across all T-box proteins (Bollag et al. 1994; Papaioannou and Silver 1998), and analysis of vertebrate T-box protein/DNA cocrystals shows that this region and in particular Ala238 interacts with target DNA (Muller and Herrmann 1997; Coll et al. 2002). The deletion allele tbx-2(ok529) is a 1082-bp in-frame deletion that removes part of the conserved DNA binding domain, and genetic analysis suggests that the lesion eliminates tbx-2 function (Roy Chowdhuri et al. 2006; Smith and Mango 2007). The similarity of the gm111 and ok529 phenotypes indicates that gm111 also results in a severe loss if not a total absence of TBX-2 function. Since gm111 heterozygous animals show no mutant phenotype (data not shown), this mutation behaves like a severe recessive loss-of-function allele. All further analysis in this article was done with the predicted null allele tbx-2(ok529) unless otherwise specified.

Figure 6.—

gm111 is a missense mutation that alters the conserved T-box binding domain. Alignment of a conserved 13-amino-acid sequence in Tbx2/3 orthologs from different species. H.s., Homo sapiens; X.l., Xenopus laevis; D.r., Danio rerio; D.m., Drosophila melanogaster; C.b., Caenorhabditis briggsae; C.e., Caenorhabditis elegans.

TBX-2 negatively regulates the cell-death pathway:

Two explanations can account for the missing PHB phenotype in tbx-2 mutant animals. One is that TBX-2 negatively regulates cell death in the PHB neuron, such that in its absence, the PHB dies. The second is that TBX-2 regulates PHB differentiation, such that in its absence the PHB is born, but does not differentiate properly and thus does not express PHB markers. To distinguish between these possibilities, we blocked the execution of programmed cell death in a tbx-2 mutant background and asked whether the missing PHB phenotype could be rescued. If TBX-2 regulates cell death, then the prediction is that the missing PHB phenotype will be rescued. If, on the other hand, TBX-2 regulates PHB differentiation, then blocking the cell-death pathway should not affect the missing cell phenotype. C. elegans has a genetically defined core “apoptosis” execution pathway (Metzstein et al. 1998). Loss of the BH3-domain containing protein EGL-1, the Apaf-1 homolog CED-4, or the Caspase-9 homolog CED-3, completely rescued the “missing” cell phenotype of tbx-2 mutants (Figure 5B). These observations suggest that TBX-2 functions as a negative regulator of the cell-death pathway for the C. elegans PHB neuron.

TBX-2 AND HAM-1 independently regulate PHB development:

We previously had shown that the protein HAM-1 regulates the asymmetric division of the HSN/PHB lineage (Guenther and Garriga 1996; Frank et al. 2005). Our hypothesis for its function, on the basis of its asymmetric cortical localization in the HSN/PHB neuroblast and on the ham-1 mutant phenotypes, proposes that HAM-1 tethers cell-fate determinants in the HSN/PHB neuroblast, causing them to be inherited by the HSN/PHB precursor cell and excluding them from its anterior sister cell, which normally dies. In this model, loss of HAM-1 allows the equal distribution of the determinants into both daughters of the neuroblast, causing the anterior cell to divide and generate an extra HSN and PHB. ham-1 mutants also have a low frequency of missing HSN and PHB neurons. We previously speculated that this loss of neurons could be due to a lower dose of determinants because they are now distributed between the two daughter cells.

This model predicts that loss of the determinants that specify HSN/PHB precursor fate would result in the loss of HSNs and PHBs. Alternatively, if several molecules are involved in specifying precursor fate, then the loss of one might result in the partial loss of these neurons, and the neuronal loss phenotype might be enhanced by loss of ham-1.

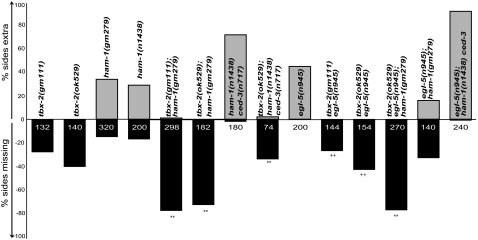

We tested this model by constructing and analyzing tbx-2; ham-1 double mutants. The strong loss-of-function alleles ham-1(n1438) and ham-1(gm279) result in some lineages that produce extra HSNs and PHBs and other lineages that fail to produce either neuron. Like the tbx-2 HSN and PHB neuron-loss phenotype, the ham-1 neuron-loss phenotype can be rescued by mutations in the cell-death pathway (Guenther and Garriga 1996; Frank et al. 2005) (Figure 7 and data not shown). The missing neuron phenotype of the tbx-2 and ham-1 mutants was significantly enhanced in tbx-2(ok529); ham-1(gm279) as well as tbx-2(gm111); ham-1(gm279) double mutants (Figure 7), suggesting that TBX-2 acts as a cell-fate determinant in the HSN/PHB lineage.

Figure 7.—

HAM-1, EGL-5, and TBX-2 act in genetically parallel pathways to specify PHB fate. The GFP-reporter gmIs13 was used to quantify the number of phasmid neurons. Y-axis denotes the percentage of sides scored with either an extra or a missing phasmid neuron. The number of sides scored is noted on the bars for each genotype. Genotypes are as indicated. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: (**) P < 0.0001 and (++) no significant difference between tbx-2 and tbx-2 egl-5 and no significant difference between tbx-2 ham-1 and tbx-2 egl-5; ham-1.

Because both TBX-2 and HAM-1 appear to regulate apoptosis in the HSN/PHB lineage, the simplest explanation for the large number of missing PHB neurons in tbx-2; ham-1 double mutants is that either the PHBs or their precursors die. The explanation that the precursors or PHBs die, however, predicts that blocking apoptosis would suppress the missing PHB phenotype of tbx-2; ham-1 mutants. Surprisingly, the ced-3(n717) mutation only partially suppressed this phenotype (Figure 7). This result suggests that besides playing a role in suppressing apoptosis, both TBX-2 and HAM-1 specify neural fate. We did not directly ask whether the missing cells scored in our assays die or whether they survive but do not express the GFP marker because of the difficulty in doing this experiment.

The Hox protein EGL-5 also specifies neural fate in the HSN/PHB lineage:

Like the loss of TBX-2, loss of EGL-5 leads to HSN migration and differentiation defects (Desai et al. 1988). The HSNs of egl-5 mutants also express PHB markers such as Psrb-6∷gfp, suggesting that the HSNs acquire differentiation traits of their sister cells (Baum et al. 1999). egl-5 mutants have no obvious PHB defect. These phenotypes and the observation that an egl-5∷lacZ transgene is expressed in the HSN but not in the PHB suggest that EGL-5 is involved in specifying the fate of the HSN, and in its absence the HSN is partially transformed into its sister cell.

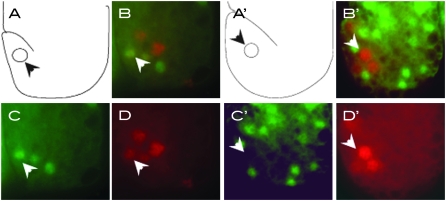

The observations described in the previous section suggest that a ham-1 mutant can be used to sensitize the background for defects in PHB development. Even though egl-5 mutants displayed no obvious PHB defect, we asked whether an egl-5 mutation could perturb PHB development in a ham-1 mutant background. We found that an egl-5 mutation significantly enhanced the missing PHB phenotype of the ham-1 mutant (Figure 7), revealing a role for EGL-5 in PHB development. It is noteworthy that the HSNs also failed to express the Psrb-6∷gfp transgene in the double mutants. This latter observation and the lack of egl-5 expression in PHB raised the possibility that EGL-5 does not control PHB development directly, but rather regulates the fate of the HSN/PHB precursor. We tested this hypothesis by asking whether the HSN/PHB precursor expressed the egl-5∷lacZ transgene, muIs13 (Wang et al. 1993). The GFP reporter gmIs20 (hlh-14∷GFP) is expressed in the HSN/PHB neuroblast as well as its daughter cell, the HSN/PHB precursor, providing a marker for cells in the lineage (Frank et al. 2003). We generated a muIs13 (egl-5∷lacZ); gmIs20 (hlh14∷GFP) strain, and costained the embryos with anti-β-galactosidase and anti-GFP antibodies. We saw that the neuroblast stained positive only for GFP (data not shown). By contrast, we did see costaining of the precursor cell with both anti-β-galactosidase and anti-GFP antibodies (Figure 8, A–D). This costaining was lost around the time when the precursor divides and also was missing in the HSN neuron, which stained only for β-galactosidase (data not shown). These observations show that egl-5 is expressed in the HSN/PHB precursor, and then later only in the HSN. Thus, EGL-5 is likely to function in two cells of the lineage. We propose that EGL-5 functions early in the HSN/PHB precursor to regulate its fate and then later in the HSN to specify its fate, making it different from its PHB sister cell. Some of the HSN defects of egl-5 mutants could be a consequence of HSN/PHB precursor abnormalities.

Figure 8.—

EGL-5 is expressed in the HSN/PHB precursor, while TBX-2 is not. (A–D) gmIs20[hlh-14∷gfp]; muIs13[egl-5∷lacZ] representative embryo around the 1.5-fold stage stained with anti-GFP (green) and anti-lacZ (red). (A) Schematic of embryo; (B) merge of anti-gfp and anti-lacZ; (C) anti-GFP; and (D) anti-lacZ. (A′–D′) muIs13[egl-5∷lacZ]; AW0095[tbx-2∷gfp] representative embryo around the 1.5-fold stage stained with anti-GFP (green) and anti-lacZ (red). (A′) Schematic of embryo; (B′) merge of anti-gfp and anti-lacZ; (C′) anti-GFP; and (D′) anti-lacZ of a representative embryo.

The missing cell phenotype of the ham-1; egl-5 double mutant could be due to either improper cell-fate specification or inappropriate cell death. Furthermore, both HAM-1 and EGL-5 could regulate fate or death in the precursor, in the HSN, or PHB neurons, or in both the precursor and the neurons. Approximately 27 and 15% of the HSN neurons are missing in egl-5 and ham-1 hermaphrodites, respectively. Both of these missing cell defects can be rescued by mutations in ced-3 (Guenther and Garriga 1996; Baum et al. 1999).

To further analyze the ham-1; egl-5 missing cell defect, we built a egl-5(n945); ham-1(n1438) ced-3(n717) triple mutant. We predicted that if the missing cell defect was entirely due to improper cell-fate specification of the PHB or the precursor (i.e., inability to express the Psrb-6∷gfp marker), the triple mutant would resemble ham-1; egl-5 double mutants and be refractory to rescue with ced-3. Alternately, if cell death of the precursor and/or the HSN/PHB neurons caused the missing cell defects, we should see a rescue of the phenotype. The triple mutant egl-5(n945); ham-1(n1438) ced-3(n717) had a penetrant extra PHB phenotype (Figure 7). This is not merely a rescue of the missing PHB defect of the ham-1; egl-5 double, but rather a synergistic enhancement of the number of cells expressing Psrb-6∷gfp. In many cases we saw two extra PHB neurons, and in some cases, even three extra neurons per side (data not shown). This presence of four “PHB-like” neurons could result if both the apoptotic cell is transformed into its sister, the HSN/PHB precursor, and the HSNs adopt traits of their sister PHB neurons. The phenotype of the triple mutant suggests that both HAM-1 and EGL-5 regulate the survival and fate of the precursor, and the HSN and PHB neurons.

tbx-2 mutations are epistatic to egl-5:

If TBX-2 regulates PHB fate, we predict that its function would be required for the HSN of egl-5 mutants to express PHB-like traits. This is indeed the case. The ectopic expression of srb-6∷gfp in egl-5 HSNs is lost in tbx-2 egl-5(n945) double mutants (Figure 7). These data corroborate the hypothesis that TBX-2 specifies “PHB fate.”

The results described above suggest that HAM-1 and EGL-5 work in parallel to regulate the fate of the precursor cell. On the basis of the lack of any obvious egl-5∷lacZ expression in the PHB, we propose that EGL-5 acts in the precursor to specify its fate, and when the precursor divides, EGL-5 function becomes restricted to its anterior daughter, the HSN. In the HSN, EGL-5 represses PHB fate, while TBX-2 specifies PHB differentiation in the posterior daughter cell. If this model is correct, then the PHB fate defects of tbx-2; ham-1 mutants should not be enhanced by the presence of an egl-5 mutation. Indeed, the PHB defects of tbx-2 egl-5; ham-1 triple mutants did not look any worse than those of tbx-2; ham-1 double mutants (Figure 7). We also predicted that ham-1 should enhance the tbx-2 egl-5 PHB defects, since it functions higher in the lineage to specify the precursor fate. Indeed, comparing the triple mutant with tbx-2 egl-5 shows a strong enhancement of the PHB phenotype (Figure 7).

A tbx-2∷gfp transgene is not expressed in the HSN/PHB precursor:

We propose that TBX-2 is a regulator of PHB fate. Does it function in the PHB neuron to specify its fate? To test whether a tbx-2∷gfp transgene is expressed within the HSN/PHB lineage, we carried out similar colabeling experiments as described above. Having established that the egl-5∷lacZ transgene is expressed in the precursor cell, we costained a strain carrying tbx-2∷gfp (Roy Chowdhuri et al. 2006) and muIs13 with both anti-GFP and anti-β-galactosidase antibodies. We saw no colabeling of the HSN/PHB precursor, suggesting that TBX-2 may not be expressed at that time (Figure 8, A′–D′). We also ruled out coexpression of tbx-2∷gfp with antibodies to EGL-43, which stain the HSN and PHB, or with antibodies to HAM-2, which stain the HSN (data not shown). Thus, we have been unable to detect expression of tbx-2∷gfp in any cells of the HSN/PHB lineage.

This observation leaves us with three possibilities. First, TBX-2 is normally expressed in the HSN/PHB lineage, but the TBX-2∷GFP levels were too low to detect or were expressed transiently and were not detected in our experiments, Second, the TBX-2∷GFP may not be expressed appropriately from this transgene, at least in cells required for the L1 arrest and HSN phenotypes. However, this transgene did rescue the PHB defects, suggesting that it should be expressed in cells involved in regulation of PHB fate (data not shown) (Roy Chowdhuri et al. 2006; Smith and Mango 2007). Third, TBX-2 could function cell nonautonomously outside the lineage to regulate HSN and PHB differentiation.

TBX-2 acts in parallel to HAM-1 and EGL-5 to regulate HSN migration:

ham-1 is a gene that is required for HSN migration (Desai et al. 1988). Since our data suggest that TBX-2 and HAM-1 work in parallel to regulate PHB cell fate, we wondered if the two genes work in a similar manner to regulate HSN migration. The double mutant tbx-2(ok529); ham-1(gm279) shows strongly synergistic HSN migration defects, suggesting that as with PHB development, the two genes operate in parallel genetic pathways for HSN migration as well (Figure 9).

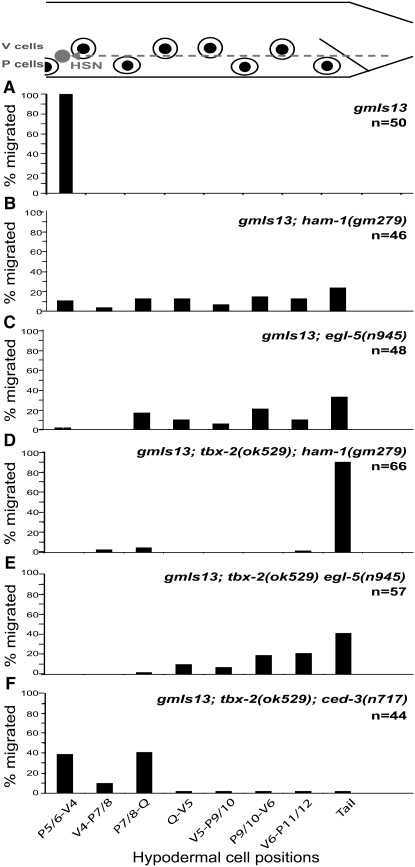

Figure 9.—

HSN migration defects in double mutants. At the top is a schematic of the posterior half of an L1 hermaphrodite. Anterior is to the left, dorsal is up. The dotted line represents the migratory route of the HSN. The positions of the V- and P-hypodermal cell nuclei are represented by eye-shaped structures, starting with P5/6 at the anteriormost position. The tick marks along each graph mark the position of the corresponding hypodermal cell aligned with respect to the diagram to the top. The y-axes of the graphs represent the percentage of neurons at each position along the anterior–posterior axis. ced-3 mutants have no HSN migration defects (not shown). (A) gmIs13; (B) gmIs13; ham-1(n1438); (C) gmIs13; egl-5(n945); (D) gmIs13; tbx-2(ok529); ham-1(gm279); (E) gmIs13; tbx-2(ok529) egl-5(n945); and (F) gmIs13; tbx-2(ok529); ced-3(n717). n, the number of HSNs scored, is indicated along graphs for each genotype.

While mutations in tbx-2 are epistatic to a mutation in egl-5 for the PHB differentiation defects (Figure 7), we found that they are synergistic for the HSN migration defects (Figure 9). We conclude that TBX-2 and EGL-5 function independently to regulate HSN migration.

HSN defects in tbx-2 are independent of the PHB differentiation defects:

Mutations in tbx-2 regulate the fate of both the PHB and the HSN. To address whether the HSN migration defects could result from the absence of the PHB neuron, we scored the HSN positions in tbx-2(ok529); ced-3(n717) double mutants. The HSN migration defects are not rescued in these mutants (Figure 9), suggesting that the HSN migration defects are not a secondary consequence of the loss of the PHB neuron.

DISCUSSION

In a screen for HSN migration mutants, we identified the gene encoding the T-box transcription factor TBX-2 as a regulator of HSN and PHB differentiation. C. elegans TBX-2 is the only C. elegans ortholog of the TBX-2/3/4/5 subfamily of T-box proteins (Agulnik et al. 1995). This class of proteins has been implicated in the specification of various tissues during embryonic development across various species, including humans (Davenport et al. 2003; Harrelson et al. 2004; Jerome-Majewska et al. 2005; Manning et al. 2006).

While this class of T-box proteins appears to act in multiple pathways, they often act downstream of BMP signaling and upstream of FGF signaling (Naiche et al. 2005; Manning et al. 2006). Since the TGFβ-receptors DAF-1 and DAF-4 are expressed in the phasmid neuron PHB (Gunther et al. 2000), it will be interesting to test whether daf-4 regulates PHB development and is genetically epistatic to tbx-2.

TBX-2 has been shown to coordinate migration of neural and neuroectodermal cells in zebrafish by mediating the downregulation of cadherins by Wnts (Fong et al. 2005). All five of the C. elegans Wnts contribute to HSN migration (Pan et al. 2006), raising the interesting possibility that tbx-2 could either be a target of Wnt signaling or regulate a Wnt signaling component. For example, this may predict that migration defects in tbx-2 will not be enhanced by mutations in Wnt components. Consistent with this idea, tbx-2(ok529) does not enhance HSN migration defects of the C. elegans Wnt, egl-20 (data not shown).

In C. elegans, TBX-2 is implicated in the regulation of ABa-derived anterior pharyngeal muscles (Roy Chowdhuri et al. 2006; Smith and Mango 2007). TBX-2 has been shown to interact with the SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC-9 and to interact genetically in a positive feedback loop with the FoxA transcription factor PHA-4 for commitment to pharyngeal muscle fate.

In vitro cell culture and mouse model studies link TBX-2/3 to the cell cycle and cellular senescence via the p19/ARF pathway (Jacobs et al. 2000; Brummelkamp et al. 2002; Lingbeek et al. 2002; Prince et al. 2004; Jerome-Majewska et al. 2005). It is yet unclear whether TBX-2 controls these phenotypes by regulating genes involved in apoptosis, cell proliferation, or both. Our analysis suggests that in C. elegans, TBX-2 regulates apoptosis in the PHB neuron.

The genetic interactions between TBX-2 and cell-death genes indicate that TBX-2 functions as a negative regulator of apoptosis for the C. elegans PHB neuron. This role of TBX-2 may be similar to the role of vertebrate Tbx3 in regulating apoptosis/senescence of rat bladder epithelial-cell carcinomas (Brummelkamp et al. 2002; Ito et al. 2005) and distinct from its role in pharyngeal muscle development in C. elegans. Thus the role of TBX-2 in the PHB neuron may provide a model genetic system to probe the mechanism of its interaction with the apoptotic machinery. In this context, it is noteworthy that the gene egl-1, which encodes a BH3-like protein that activates the C. elegans cell-death pathway, has a cluster of seven putative T-box binding sites within the sequence upstream of the transcription start site for egl-1 (A. Garnett, personal communication). It is also possible that the role of TBX-2 in regulating HSN migration is analogous to the role of vertebrate Tbx2/3 in regulating cell migrations (Naiche et al. 2005).

Mutations in tbx-2 affect both the HSN and PHB sister neurons. For several reasons, we suspect that rather than acting at the level of the HSN/PHB precursor, TBX-2 acts independently to regulate HSN and PHB fates (Figure 10). First, while TBX-2 regulates PHB survival, it does not appear to regulate the survival of the precursor cell or of the HSN. Second, mutations in the apoptotic machinery can rescue the missing PHB defect, but do not rescue the HSN migration defect (Figure 9). This difference also indicates that the HSN migration defect is not a secondary consequence of missing PHBs. Third, the penetrance of the two phenotypes is different, and we have seen no obvious correlation between the HSN and PHB phenotypes. Sides missing PHBs, for example, can have normally positioned or misplaced HSNs (data not shown).

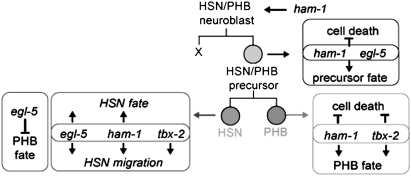

Figure 10.—

Model summarizing genetic data implicating TBX-2, HAM-1, and EGL-5 as regulators of the survival and fate of the precursor cell, the HSN neuron, and the PHB neuron, as well as migration of the HSN neuron. We propose that egl-5 acts to promote HSN development and to inhibit PHB fate in the HSNs. These models are not mutually exclusive. By inhibiting PHB fate, for example, egl-5 could promote the expression of HSN traits.

Genetic interactions suggest that TBX-2 and HAM-1 function in parallel to regulate the HSN/PHB lineage (Figure 10). HAM-1 has previously been shown to localize asymmetrically to the cell cortex of the HSN/PHB neuroblast and to be inherited by the HSN/PHB precursor. Because the daughter cell that does not inherit HAM-1 is transformed in ham-1 mutants, we proposed that HAM-1 acts as a tether that segregates cell-fate determinants asymmetrically to the precursor (Guenther and Garriga 1996; Frank et al. 2005). But ham-1 mutants occasionally are missing HSNs and PHBs. To explain this phenotype in the context of the tether model, we propose that when determinants are distributed to both cells in the mutant, their levels can fall below a threshold necessary for neural specification. This model predicts that loss of genes involved in HSN and PHB specification will synergize with ham-1 mutations to generate a highly penetrant missing cell phenotype. Consistent with this prediction, tbx-2; ham-1 double mutants are strongly synergistic and lack PHB neurons ∼75–80% of the time. The mutations in the two genes are also strongly synergistic for HSN migration: we never detect the HSNs in their normal positions and rarely detect them along their migration route in tbx-2; ham-1 double mutants.

We also found that the loss of PHB neurons caused by ham-1 mutations was enhanced by loss of egl-5. EGL-5 is a Hox protein that specifies the fates of several cells located in the tail of the worm (Chisholm 1991; Clark et al. 1993; Wang et al. 1993). EGL-5 is crucial for HSN development, controlling its ability to migrate during embryonic development and its later differentiation during larval and adult stages of development (Desai et al. 1988). EGL-5 acts by activating the ham-2 and unc-86 transcription factor genes. In the absence of egl-5 or both ham-2 and unc-86, the HSN takes on traits of its sister cell, the PHB (Baum et al. 1999). Consistent with the model that TBX-2 regulates PHB fate, tbx-2 is required for egl-5 HSNs to express PHB markers. By contrast, tbx-2 mutations enhanced the HSN defects of egl-5 mutants. These data together lead us to propose that TBX-2 has two independent functions in the HSN/PHB lineage: to repress cell death and activate cell differentiation in the PHB and to promote HSN migration in parallel to EGL-5 (Figure 10).

Any further understanding of the genetic interactions among the ham-1, egl-5, and tbx-2 genes will require an analysis of whether HAM-1 regulates the expression or distribution of TBX-2 or EGL-5. The tools for this type of study are currently lacking.

The role of EGL-5 in PHB development that was revealed in the egl-5; ham-1 double mutant supports the idea that ham-1 mutants may provide a unique background to discover genes involved in HSN and PHB development. Both the HSN and PHB defects are also much more severe in gm345; ham-1 double mutants than in either of the single mutants (data not shown). All of these observations taken together suggest that ham-1 mutants can function as a sensitizing background to identify genes involved in HSN and PHB specification. ham-1 mutations are pleiotropic, affecting many asymmetric neuroblast divisions that generate neurons and apoptotic cells in the embryo (Guenther and Garriga 1996; Frank et al. 2005). We therefore believe that the ham-1 mutant might provide a useful background to identify neural specification genes for neurons arising from all these lineages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alison Woollard and Pete Okkema for strains. We thank Aaron Garnett for in silico analysis of the egl-1 promoter sequence for consensus T-box binding sites. We also thank Shaun Cordes for many helpful discussions and suggestions and Aaron Garnett for comments on the manuscript. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by NIH grant NS-42213 to G.G.

References

- Agulnik, S. I., R. J. Bollag and L. M. Silver, 1995. Conservation of the T-box gene family from Mus musculus to Caenorhabditis elegans. Genomics 25 214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, P. D., C. Guenther, C. A. Frank, B. V. Pham and G. Garriga, 1999. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene ham-2 links Hox patterning to migration of the HSN motor neuron. Genes Dev. 13 472–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag, R. J., Z. Siegfried, J. A. Cebra-Thomas, N. Garvey, E. M. Davison et al., 1994. An ancient family of embryonically expressed mouse genes sharing a conserved protein motif with the T locus. Nat. Genet. 7 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp, T. R., R. M. Kortlever, M. Lingbeek, F. Trettel, M. E. MacDonald et al., 2002. TBX-3, the gene mutated in ulnar-mammary syndrome, is a negative regulator of p19ARF and inhibits senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 277 6567–6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, A., 1991. Control of cell fate in the tail region of C. elegans by the gene egl-5. Development 111 921–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. G., A. D. Chisholm and H. R. Horvitz, 1993. Control of cell fates in the central body region of C. elegans by the homeobox gene lin-39. Cell 74 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. G., and C. Chiu, 2003. C. elegans ZAG-1, a Zn-finger-homeodomain protein, regulates axonal development and neuronal differentiation. Development 130 3781–3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll, M., J. G. Seidman and C. W. Muller, 2002. Structure of the DNA-bound T-box domain of human TBX3, a transcription factor responsible for ulnar-mammary syndrome. Structure 10 343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, S., C. A. Frank and G. Garriga, 2006. The C. elegans MELK ortholog PIG-1 regulates cell size asymmetry and daughter cell fate in asymmetric neuroblast divisions. Development 133 2747–2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T. G., L. A. Jerome-Majewska and V. E. Papaioannou, 2003. Mammary gland, limb and yolk sac defects in mice lacking Tbx3, the gene mutated in human ulnar mammary syndrome. Development 130 2263–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, C., G. Garriga, S. L. McIntire and H. R. Horvitz, 1988. A genetic pathway for the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSN motor neurons. Nature 336 638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong, S. H., A. Emelyanov, C. Teh and V. Korzh, 2005. Wnt signalling mediated by Tbx2b regulates cell migration during formation of the neural plate. Development 132 3587–3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, C. A., P. D. Baum and G. Garriga, 2003. HLH-14 is a C. elegans Achaete-Scute protein that promotes neurogenesis through asymmetric cell division. Development 130 6507–6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, C. A., N. C. Hawkins, C. Guenther, H. R. Horvitz and G. Garriga, 2005. C. elegans HAM-1 positions the cleavage plane and regulates apoptosis in asymmetric neuroblast divisions. Dev. Biol. 284 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitai, Z., T. W. Yu, E. A. Lundquist, M. Tessier-Lavigne and C. I. Bargmann, 2003. The netrin receptor UNC-40/DCC stimulates axon attraction and outgrowth through enabled and, in parallel, Rac and UNC-115/AbLIM. Neuron 37 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, P. L., and J. Kimble, 1993. The mog-1 gene is required for the switch from spermatogenesis to oogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 133 919–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, C., and G. Garriga, 1996. Asymmetric distribution of the C. elegans HAM-1 protein in neuroblasts enables daughter cells to adopt distinct fates. Development 122 3509–3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther, C. V., L. L. Georgi and D. L. Riddle, 2000. A Caenorhabditis elegans type I TGF beta receptor can function in the absence of type II kinase to promote larval development. Development 127 3337–3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrelson, Z., R. G. Kelly, S. N. Goldin, J. J. Gibson-Brown, R. J. Bollag et al., 2004. Tbx2 is essential for patterning the atrioventricular canal and for morphogenesis of the outflow tract during heart development. Development 131 5041–5052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata, J., H. Nakagoshi, Y. Nabeshima and F. Matsuzaki, 1995. Asymmetric segregation of the homeodomain protein Prospero during Drosophila development. Nature 377 627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeshima-Kataoka, H., J. B. Skeath, Y. Nabeshima, C. Q. Doe and F. Matsuzaki, 1997. Miranda directs Prospero to a daughter cell during Drosophila asymmetric divisions. Nature 390 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, A., M. Asamoto, N. Hokaiwado, S. Takahashi and T. Shirai, 2005. Tbx3 expression is related to apoptosis and cell proliferation in rat bladder both hyperplastic epithelial cells and carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 219 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. J., P. Keblusek, E. Robanus-Maandag, P. Kristel, M. Lingbeek et al., 2000. Senescence bypass screen identifies TBX2, which represses Cdkn2a (p19(ARF)) and is amplified in a subset of human breast cancers. Nat. Genet. 26 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome-Majewska, L. A., G. P. Jenkins, E. Ernstoff, F. Zindy, C. J. Sherr et al., 2005. Tbx3, the ulnar-mammary syndrome gene, and Tbx2 interact in mammary gland development through a p19Arf/p53-independent pathway. Dev. Dyn. 234 922–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K., and C. Li, 2004. Expression and regulation of an FMRFamide-related neuropeptide gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Comp. Neurol. 475 540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich, J. A., L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1995. Asymmetric segregation of Numb and Prospero during cell division. Nature 377 624–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, R., and J. A. Campos-Ortega, 1996. inscuteable, a neural precursor gene of Drosophila, encodes a candidate for a cytoskeleton adaptor protein. Dev. Biol. 174 65–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, R., W. Chia, L. Y. Jan, Y. N. Jan and J. A. Knoblich, 1996. Role of inscuteable in orienting asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Nature 383 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., K. Kim and L. S. Nelson, 1999. FMRFamide-related neuropeptide gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. Brain Res. 848 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., L. S. Nelson, K. Kim, A. Nathoo and A. C. Hart, 1999. Neuropeptide gene families in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 897 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingbeek, M. E., J. J. Jacobs and M. van Lohuizen, 2002. The T-box repressors TBX2 and TBX3 specifically regulate the tumor suppressor gene p14ARF via a variant T-site in the initiator. J. Biol. Chem. 277 26120–26127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, L., K. Ohyama, B. Saeger, O. Hatano, S. A. Wilson et al., 2006. Regional morphogenesis in the hypothalamus: a BMP-Tbx2 pathway coordinates fate and proliferation through Shh downregulation. Dev. Cell 11 873–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzstein, M. M., G. M. Stanfield and H. R. Horvitz, 1998. Genetics of programmed cell death in C. elegans: past, present and future. Trends Genet. 14 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, C. W., and B. G. Herrmann, 1997. Crystallographic structure of the T domain-DNA complex of the Brachyury transcription factor. Nature 389 884–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiche, L. A., Z. Harrelson, R. G. Kelly and V. E. Papaioannou, 2005. T-box genes in vertebrate development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39 219–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C. L., J. E. Howell, S. G. Clark, M. Hilliard, S. Cordes et al., 2006. Multiple Wnts and frizzled receptors regulate anteriorly directed cell and growth cone migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell 10 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou, V. E., and L. M. Silver, 1998. The T-box gene family. BioEssays 20 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince, S., S. Carreira, K. W. Vance, A. Abrahams and C. R. Goding, 2004. Tbx2 directly represses the expression of the p21(WAF1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 64 1669–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhyu, M. S., and J. A. Knoblich, 1995. Spindle orientation and asymmetric cell fate. Cell 82 523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhyu, M. S., L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1994. Asymmetric distribution of numb protein during division of the sensory organ precursor cell confers distinct fates to daughter cells. Cell 76 477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy Chowdhuri, S., T. Crum, A. Woollard, S. Aslam and P. G. Okkema, 2006. The T-box factor TBX-2 and the SUMO conjugating enzyme UBC-9 are required for ABa-derived pharyngeal muscle in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 295 664–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C. P., L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1997. Miranda is required for the asymmetric localization of Prospero during mitosis in Drosophila. Cell 90 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. A., and S. E. Mango, 2007. Role of T-box gene tbx-2 for anterior foregut muscle development in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 302 25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spana, E. P., C. Kopczynski, C. S. Goodman and C. Q. Doe, 1995. Asymmetric localization of numb autonomously determines sibling neuron identity in the Drosophila CNS. Development 121 3489–3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J. E., E. Schierenberg, J. G. White and J. N. Thomson, 1983. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 100 64–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent, C., N. Tsuing and H. R. Horvitz, 1983. Egg-laying defective mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 104 619–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troemel, E. R., J. H. Chou, N. D. Dwyer, H. A. Colbert and C. I. Bargmann, 1995. Divergent seven transmembrane receptors are candidate chemosensory receptors in C. elegans. Cell 83 207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura, T., S. Shepherd, L. Ackerman, L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1989. numb, a gene required in determination of cell fate during sensory organ formation in Drosophila embryos. Cell 58 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. B., M. M. Muller-Immergluck, J. Austin, N. T. Robinson, A. Chisholm et al., 1993. A homeotic gene cluster patterns the anteroposterior body axis of C. elegans. Cell 74 29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J. G., E. Southgate, J. N. Thomson and S. Brenner, 1986. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 314 1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]