Abstract

Objective

To verify what information from oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) independently predicts mortality.

Research Design and Methods

1401 initially non-diabetic participants from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, aged 17–95 years, with one or more OGTT (median=2, range 1–8) with insulin and glucose measurements measured every 20 minutes over 2 hours. Proportional hazard using the longitudinally collected data and Bayesian model averaging were used to examine the association of OGTT measurements individually and grouped with mortality adjusting for covariates.

Results

Participants were followed for a median 20.3 years (range 0.5 – 40 years). The first hour OGTT glucose and insulin levels increased only modestly with age; whereas levels during the second hour increased more than 4% per decade. Individually, the 100-and 120-minute glucose measures and the fasting and 100-minute insulin levels were all independent predictors of mortality. When all measures were considered together, only higher 120-minute glucose was a significant independent risk factor for mortality.

Conclusion

The steeper rise with age of the OGTT 2-hour glucose values and the prognostic primacy of the 120 minute glucose value for mortality is consistent with previous reports and suggests the value of using the OGTT in clinical practice.

Many but not all studies have found a near-linear association between fasting plasma glucose levels above 100 mg/dl and mortality (1). Plasma glucose two hours after an oral glucose load is also a strong predictor of mortality regardless of fasting plasma glucose level (2,3), and may actually be a better predictor of mortality than the fasting level (4).

It has been proposed that in early stages of glucose metabolism dysregulation, fasting and 2 hour plasma glucose measures during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) may be normal or slightly elevated, but the amount of insulin necessary to maintain this equilibrium is supra-physiological (5). This state of “insulin resistance” may have detrimental consequences on health. However, little evidence exists that hyperinsulinemia either fasting, or with a glucose challenge, is a risk factor for mortality (6). Thus the clinical usefulness of measuring insulin remains uncertain.

Using data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), we examined longitudinal change in glucose and insulin in response to OGTT, and the association of different glucose and insulin measurements on mortality.

Research Design and Methods

Study population

BLSA participants are community-dwelling volunteers with above-average education, income and access to medical care (7). Participants underwent extensive evaluations bi-annually. Participants who were non-diabetic at the initial OGTT evaluation and with at least one OGTT with both glucose and insulin measurements were included in this study. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and all participants provided written informed consent.

Analysis was restricted to OGTT performed prior to 1995 (when laboratory procedures were modified). Overall, 1510 BLSA participants (age 17 to 95 years) were eligible, of whom 109 had diabetes at the time of their initial OGTT, defined as a fasting glucose >= 7.0 mm/l (126 mg/dl), 2 hour OGTT glucose measurement >= 11.1 mm/l (200 mg/dl), history of diabetes or current use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin, leaving 1401 participants with 3727 observations (424 subjects with 1 observation, 343 with 2 observations, 262 with 3 observations, and 372 with 4 or more observations).

OGTT

OGTT assessments began in 1959 using 1.75 g glucose/kg body weight glucose challenge, which was changed to 40 g/m2 body surface area in 1977, following recommended guidelines. Consistent with previous research (2,3), to convert OGTT results across methods we regressed glucose and insulin levels at each OGTT time point on a fourth order polynomial of the glucose load which was centered at 75 grams. Adjusted measurements no longer depended on glucose load.

Participants were observed overnight on the research ward, beginning fasting at 8 pm and received the OGTT between 7 and 8 am. Blood samples were drawn at 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 and 120 minutes. Glucose levels were measured using the ferricyanide reduction method (Technico-Auto- Analyzer) before 1977 and the glucose oxidase method from 1977 to present, with the Beckman glucose analyzer (1977–1983), Abbott Laboratories ABA 200 ATC Series II Biochromatic Analyzer (1983–1992), Abbott Spectrum CCX (1992 to present). Plasma insulin was measured using radio-immunoassay (8). The lower limit of detection for this assay is 15 pmol/ml, interassay coefficient of variation is 11.5 with intra-assay coefficient of variation of 6% (9).

Covariates

Height, weight, and seated blood pressure were measured by standard methods. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height (meters) squared. Waist circumference (cm) was measured as the smallest circumference between the umbilicus and lower ribs. Smoking history was assessed using a standard questionnaire.

Mortality

Deaths were ascertained by telephone follow-up of inactive participants, correspondence from relatives, and search of the National Death Index. Cause of death was determined by the consensus of three physicians reviewing available information.

Statistical Analysis

Data are summarized as mean ±SD unless otherwise stated. Differences in baseline characteristics (Table 1) between survivors and decedents were tested by age and sex adjusted ancova or logistic regressions as appropriate.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants at First Evaluation

| Survivors | Decedents | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number Subjects | 931 | 470 | |

| Percent Female | 42.6 | 24.9 | |

| Age | 45.2 (15.5) | 69.3 (11.7) | <0.0001 |

| Age (Censor,Death) | 68.3 (15.9) | 83.0 (10.8) | <0.0001 |

| Time Follow-up | 23.2 (5.2) | 13.7 (6.7) | <0.0001 |

| OGTT | |||

| Glucose (mmol/l) | |||

| Fasting | 5.3 (0.4) | 5.5 (0.4) | 0.48 |

| 20 minutes | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.6 (1.1) | 0.06 |

| 40 minutes | 9.0 (1.7) | 9.2 (1.6) | 0.03 |

| 60 minutes | 8.5 (2.1) | 9.4 (2.0) | 0.71 |

| 80 minutes | 7.7 (2.1) | 8.9 (2.0) | 0.11 |

| 100 minutes | 7.1 (1.8) | 8.3 (1.9) | 0.002 |

| 120 minutes | 6.5 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.7) | 0.0001 |

| Insulin (pmol/l) | |||

| Fasting | 53 (34) | 53 (35) | 0.42 |

| 20 minutes | 224 (153) | 209 (153) | 0.27 |

| 40 minutes | 373 (250) | 348 (239) | 0.50 |

| 60 minutes | 376 (249) | 400 (282) | 0.87 |

| 80 minutes | 349 (242) | 403 (278) | 0.67 |

| 100 minutes | 317 (239) | 385 (286) | 0.28 |

| 120 minutes | 272 (207) | 341 (256) | 0.12 |

| HOMA-IR units | 2.13 (1.43) | 2.37 (1.84) | 0.38 |

| Glucose Area+ (mmol* min/L) | 917 (172) | 1005 (165) | 0.46 |

| Insulin Area+ (pmol* min/L) | 36468 (21462) | 39270 (23772) | 0.92 |

| Covariates | |||

| Weight (kg) | 72.8 (12.3) | 72.8 (14.2) | 0.68 |

| Height (cm) | 172.1 (9.8) | 170.8 (9.0) | 0.02 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 (3.5) | 24.8 (3.4) | 0.08 |

| Waist (cm) | 82.6 (11.5) | 87.8 (10.0) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP (mm/Hg) | 119.5 (15.9) | 136.2 (20.5) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm/Hg) | 77.2 (10.2) | 81.2 (10.8) | <0.0001 |

| Current Smokers (%) | 17.7 | 14.1 | 0.0003 |

adjusted for age and sex

Glucose and Insulin area are the integrated areas under the curve.

From the 3727 observations, 2.0% of the OGTT glucose and insulin measurements and 0.6% of covariate data were missing. Missing data were imputed using the MICE program (10) with five replicated datasets. Survival models were based on the first imputation while all other analyses use the average of the five imputations. The remaining four imputed datasets produced the same conclusions.

Basal insulin resistance was estimated by the homeostatic assessment model (HOMA) was calculated using fasting glucose and insulin levels as an assessment of basal insulin resistance (11). Integration of the glucose and insulin OGTT curves was calculated by the standard trapezoid method.

Proportional hazard models using all longitudinally collected OGTT data were used to examine the relationship between glucose and insulin levels at each OGTT time point and time to death with three hierarchical models that 1) adjusted for date and sex, 2) added age, and 3) added other covariates. The survival model used all longitudinally collected OGTT data though a time-dependent approach based on the Anderson-Gill formulation of a counting process using the survival functions developed by Therneau. (12).

To examine which OGTT measurements independently predicted mortality, we used a standard backward elimination to obtain a parsimonious model with all variables showing p<0.10. Additionally, we fitted a Bayesian model averaging (BMA; 13) to identify the best set of predictors for mortality across all feasible models. Because BMA used the initial evaluation, the effects of diabetes on mortality would be underestimated because of the exclusion of those who were diabetic at initial evaluation. Therefore, we repeated the BMA analysis including diabetic participants.

A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. All analyses and graphs were completed using R version 2.4.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org).

Results

There were 470 deaths and 931 surviving participants as of January 2006. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Those who died were older initially, had shorter follow-up time, tended to have higher BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and were less likely to smoke than those who survived.

At the initial evaluation, average glucose values during the OGTT were higher in those who died than those who survived (Table 1). After adjusting for age and sex, glucose at 40, 100 and 120 minutes were higher in those who died compared to survivors, while insulin levels did not differ at any time point. In adjusted analyses, HOMA, integrated glucose and integrated insulin were not statistically different according to survivorship (Table 1).

In analyses that considered longitudinal trends, all OGTT glucose levels increased with follow-up time (p<0.0001), but the rate of change was lowest for the fasting state ( 0.07 mmol/l/10 yr) and increased progressively for subsequent OGTT time points (e.g. rate at 60 minutes = 0.37 mmol/l/10 yr, and rate at 120 minutes= 0.42 mmol/l/10yr). Corresponding rates for insulin were 1.32 pmol/l/10 yr for fasting, 12.90 pmol/l/10 yr for 60 minutes, and for 128.92 pmol/l/10 yr for 120 minutes.

Proportional hazard models using all longitudinally collected data evaluated the individual relative risk of mortality for each OGTT measure (Table 2). Adjusting for age, date and sex, 100- and 120-minute glucose, fasting insulin, 100-minute insulin, and HOMA were associated with all cause mortality. These associations persisted after further adjustments for BMI, waist circumference, diastolic and systolic blood pressure, lipids and smoking. Of the 326 deaths, 134 were considered cardiovascular deaths. In adjusted analyses, only 120 min glucose and integrated glucose were significant predictors of mortality (Table 2, Model 4).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratio from Time Dependent Survival Models for Glucose (per mmol/L) and Insulin (per 100 pmol/ml) Measurements from the Longitudinally Collected OGTT

| All Cause Mortality | Cardiovascular Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Univariate Date, Sex | Model 2 Univariate Age, Date,Sex | Model 3 Univariate Age, Date, Sex, Covariates* | Model 4 Univariate Age, Date, Sex, Covariates* | |

| Glucose | ||||

| Fasting | 1.34 (1.14,1.59) | 1.12 (0.96,1.32) | 1.18 (0.99,1.39) | 1.11 (0.80,1.55) |

| 20 min | 1.06 (0.99,1.14) | 1.02 (0.94,1.10) | 1.01 (0.94,1.10) | 1.06 (0.91,1.23) |

| 40 min | 1.00 (0.95,1.05) | 0.98 (0.94,1.04) | 0.99 (0.94,1.04) | 0.99 (0.89,1.10) |

| 60 min | 1.10 (1.06,1.14) | 1.03 (0.98,1.07) | 1.03 (0.99,1.08) | 1.02 (0.94,1.11) |

| 80 min | 1.16 (1.12,1.20) | 1.04 (0.99,1.08) | 1.04 (0.99,1.08) | 1.04 (0.96,1.12) |

| 100 min | 1.20 (1.16,1.24) | 1.05 (1.00,1.09) | 1.05 (1.00,1.09) | 1.06 (0.98,1.14) |

| 120 min | 1.22 (1.17,1.27) | 1.06 (1.02,1.10) | 1.06 (1.01,1.11) | 1.08 (1.00,1.18) |

| Insulin | ||||

| Fasting | 1.18 (0.91,1.52) | 1.34 (1.03,1.74) | 1.42 (1.07,1.89) | 1.03 (0.60,1.76) |

| 20 min | 0.97 (0.92,1.03) | 1.00 (0.95,1.06) | 1.01 (0.96,1.06) | 0.99 (0.90,1.08) |

| 40 min | 0.96 (0.92,1.00) | 1.00 (0.96,1.04) | 1.00 (0.96,1.03) | 1.02 (0.96,1.09) |

| 60 min | 1.00 (0.97,1.04) | 1.01 (0.98,1.05) | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 1.00 (0.94,1.06) |

| 80 min | 1.04 (1.01,1.07) | 1.03 (0.99,1.06) | 1.02 (0.99,1.06) | 0.98 (0.92,1.04) |

| 100 min | 1.07 (1.04,1.10) | 1.04 (1.01,1.07) | 1.04 (1.01,1.07) | 1.01 (0.95,1.07) |

| 120 min | 1.06 (1.03,1.09) | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 1.01 (0.98,1.05) | 1.02 (0.96,1.08) |

| HOMA-IR | 1.05 (0.99,1.10) | 1.07 (1.01,1.13) | 1.09 (1.02,1.16) | 1.02 (0.90,1.16) |

| Glucose integrated/100 | 1.16 (1.11,1.21) | 1.03 (0.99,1.08) | 1.03 (0.98,1.08) | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) |

| Insulin integrated/1000 | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 1.00 (1.00,1.001) | 1.01 (0.97,1.06) |

Each row is a proportional hazard model with only the specific measure from the OGTT entered as the risk variable in the analysis. The model uses the longitudinally collected measure and covariates as time dependent variables. Results are from the first imputation. Note results were essentially the same for imputations 2 through 5.

Covariates included systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference, smoking status, and cholesterol.

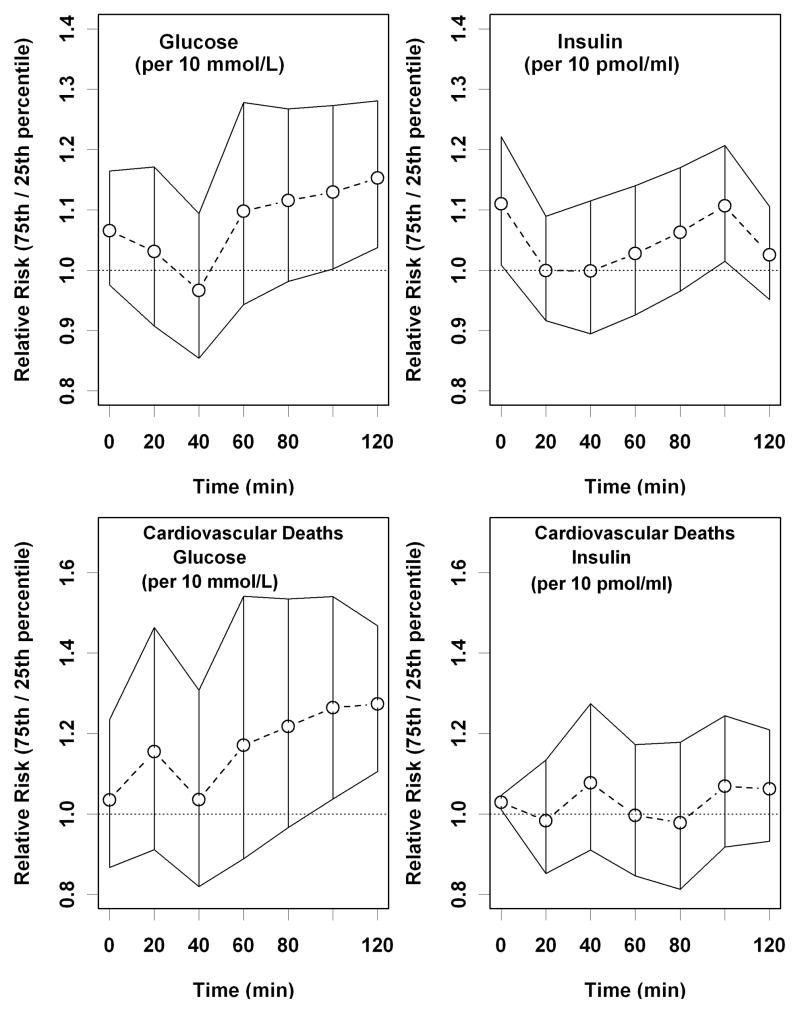

For each OGTT measure, Figure 1a presents risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) comparing risk of mortality associated with being at the 75th percentile versus the 25th percentile adjusted for age, date and sex. The greatest discernable risk was found with the 100- and 120-minute glucose measurements. Figure 1b shows a similar result for cardiovascular mortality.

Figure 1.

Age,date and sex-adjusted risk ratio (RR) for mortality comparing the 75th percentile versus the 25th percentile for the time-specific measurement, adjusted for insulin and glucose OGTT. The graph shows the median RR and 95 percent confidence intervals at each time point: (a) All-cause mortality, (b) Cardiovascular mortality.

From the longitudinal survival model including all glucose and insulin measures, we removed variables not independently associated with mortality. In the final parsimonious model, 100-minute insulin (RR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.05–1.17 per 100 pmol/ml increase), 120-minute insulin (RR=0.90, CI: 0.85–0.92), 40-minute glucose (RR=0.92, CI: 0.87–0.97 per mmol/L increase), 120-minute glucose (RR=1.10, CI: 1.05–1.16), and HOMA (RR=1.07, CI:1.00–1.13) were independently associated with greater mortality. Since the selection of variables with this method may be strongly influenced by collinearity, we performed a confirmatory analysis using BMA, which assesses uncertainty by exploring multiple models and providing weighted probabilities that coefficients are not equal to zero. Using data from the first evaluation, 120-minute glucose was the only variable in the BMA model with a probability greater than 10% (16.4%) that the regression coefficient was not zero (i.e. no association with mortality). When the 109 participants classified as diabetic at baseline were included in the BMA, the probability that the 120-minute glucose regression coefficient was not zero was 93.4%, while fasting insulin was only 15.5%. Fasting glucose was not an independent predictor of mortality in these models.

Discussion

In a large population of men and women aged 17 to 95 years at initial OGTT, higher 120-minute glucose level was the single OGTT measure consistently and independently associated with mortality.

Independent of age and sex, fasting glucose, 120-minute glucose, fasting insulin and 100-minute insulin were associated with higher mortality. When considering all glucose and insulin measurements together, only the 120-minute glucose remained prognostic for mortality, independent of age, date and sex. Although the 100- and 120-minute insulin, 40-minute glucose, and HOMA were statistically independent predictors of mortality in the parsimonious model, the prognostic information contributed by the other four variables was almost negligible. This observation is consistent with Sorkin et al (3) who found that the 120-minute glucose measurement improved mortality prediction over using fasting glucose alone. However, these authors did not consider the predictive value of the 120-minute measure alone.

Why might 120-minute glucose be the most robust predictor of mortality? It is possible that as long as beta cells secrete enough insulin to maintain euglycemia, consequences of elevated blood glucose are avoided, regardless of the amount of insulin necessary to maintain glucose homeostasis (14). Although this interpretation contrasts, at least in part, with the report by Sorkin et al (3) which focused on categorical characterizations, e.g. normal, impaired and diabetic, we suggest that a more refined risk assessment can be obtained by examining the continuous range 120-minute glucose values. Alternatively, the 120-minute glucose could be a marker of poor health. Deteriorating health may cause a progressive inability to respond to a glucose challenge, possibly due to a loss of resiliency in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis resulting in prolonged secretion of glucocorticoids following challenge (15).

Our findings do not imply that insulin resistance is not critical in the development of glucose impairment and diabetes. HOMA-IR was associated with mortality independent of the covariates, although its predictive value substantially diminished after adjusting for 120-minute glucose. Since calculating HOMA-IR does not require an OGTT, its clinical usefulness remains high. Interestingly, in preliminary analyses, fasting insulin was a significant, independent predictor of mortality. The ratio between fasting insulin and glucose during the OGTT is a marker of prompt homeostatic response, while fasting insulin depends on long term response which has 8–10 hours to reach a steady state and is also influenced by change in hormonal level characteristic of the morning awakening (e.g. cortisol, catecholamines). The insulin level required to reach steady state over a long time period may be a better indicator of the overall homeostatic capability. In addition, the insulin assay used in this study detects the proinsulin des (64–65) and proinsulin split (65–66) which may partially mask the effect of insulin on mortality.

The BLSA population is well-educated and tends to be health seeking, which may limit generalizability of these findings to similar populations. However, previous reports from the BLSA involving glucose (2,3,16) and other systems (e.g., 17,18,6) have been consistent with observations from more general populations. In conclusion, consistent with Sorkin et al (3) we find that the OGTT is an important tool for assessing glucose homeostasis. Information provided by fasting glucose can be usefully complemented by evaluating the 120 minute glucose. Although investigators have proposed that the shape of the OGTT response curve (19), as well as OGTT indices of insulin release and sensitivity may be informative (20,21,22), we found no evidence to support of these hypotheses.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

References

- 1.Balkau B, Bertrais S, Ducimetiere P, Eschwege E. Is there a glycemic threshold for mortality risk? Diabetes Care. 1999;22:696–699. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meigs JB, Muller DC, Nathan DM, Blake DR, Andres R. The natural history of progression from normal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Diabetes. 2003;52:1475–1484. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorkin JD, Muller DC, Fleg JL, Andres R. The relation of fasting and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose concentrations to mortality: Data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging with a critical review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2626–2632. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DECODE Study Group. Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetic Association diagnostic criteria. Lancet. 1999;354:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeFronzo RA, Bonadonna RC, Ferrannini E. Pathogenesis of NIDDM. A balanced overview. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:318–368. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenzen M, Ryden L, Ohrvik J, Bartnik M, Malmberg K, Scholte OP, Reimer W, Simoons ML. Diabetes known or newly detected, but not impaired glucose regulation, has a negative influence on 1-year outcome in patients with coronary artery disease: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on diabetes and the heart. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2969–2974. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shock NW, Greulich RC, Andres R, Arenberg D, Costa PT, Jr, Lakatta EG, Tobin JD. Normal Human Aging: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. (NIH Publication 84–2450) Washington, DC: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1984; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soeldner JS, Slone D. Critical variables in the radioimmunoassay of serum insulin using the double antibody technic. Diabetes. 1965;14:771–779. doi: 10.2337/diab.14.12.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller DC, Elahi D, Tobin JD, Andres R. Insulin response during the oral glucose tolerance test: the role of age, sex, body fat and the pattern of fat distribution. Aging (Milano) 1996;8:13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03340110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Buuren S, Oudshoorn CGM. Multivariate imputation by chained equations: MICE V1.0 User’s Manual. Report PG/VGZ/00.038. Leiden: TNO Preventie en Gezondheid; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace TM, Matthews DR. The assessment of insulin resistance in man. Diabet Med. 2002;19:527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data extending the Cox model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoeting JA, Madigan D, Raftery AE, Volinsky CT. Bayesian model averaging: a tutorial. Stat Sci. 1999;14:382–417. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wild SH, Smith FB, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG. Criteria for previously undiagnosed diabetes and risk of mortality: 15-year follow-up of the Edinburgh Artery Study cohort. Diabet Med. 2005;22:490–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeman TE, Robbins RJ. Aging and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to challenge in humans. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:233–60. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blake DR, Meigs JB, Muller DC, Najjar SS, Andres R, Nathan DM. Impaired glucose tolerance, but not impaired fasting glucose, is associated with increased levels of coronary heart disease risk factors: results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Diabetes. 2004;53:2095–2100. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2001;86:724–731. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe JW, Andres R, Tobin JD, Norris AH, Shock NW. The effect of age on creatinine clearance in men: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. J Gerontol. 1976;31:155–163. doi: 10.1093/geronj/31.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tschritter O, Fritsche A, Shirkavand F, Machicao F, Häring H, Stumvoll M. Assessing the shape of the glucose curve during an oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1026–1033. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Järvinen, Van Haeften T, Renn W, Gerich J. Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:295–301. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mari A, Pacini G, Murphy E, Ludvik B, Nolan JJ. A model-based method for assessing insulin sensitivity from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:539–548. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]