Abstract

Hepcidin, a liver-derived protein that restricts enteric iron absorption, is the key regulator of body iron content. Several proteins induce expression of the hepcidin-encoding gene Hamp in response to infection or high levels of iron. However, mechanism(s) of Hamp suppression during iron depletion are poorly understood. Here we describe mask, a recessive, chemically induced mutant mouse phenotype, characterized by progressive loss of body but not facial hair and microcytic anemia. The mask phenotype results from reduced absorption of dietary iron caused by high levels of hepcidin, and is due to a splicing defect in the transmembrane serine protease 6 gene Tmprss6. Overexpression of normal TMPRSS6 protein suppresses activation of the Hamp promoter, and the TMPRSS6 cytoplasmic domain mediates Hamp suppression via proximal promoter element(s). TMPRSS6 is an essential component of a pathway that detects iron deficiency and blocks Hamp transcription, permitting enhanced dietary iron absorption.

Iron is an essential cofactor for a host of metabolic reactions, necessary for function of the oxygen carrying protein hemoglobin and proteins of the electron transport chain. Though required for life, iron is also a toxic element when present in excess, and body iron content is normally maintained within narrow limits, controlled by the efficiency of intestinal iron absorption. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron absorption (1), binds to ferroportin, the channel for cellular iron efflux, and causes internalization and proteolysis of the channel, preventing release of iron from macrophages or intestinal cells (2) into the plasma. In this manner, hepcidin lowers plasma iron levels, and chronic elevation of hepcidin levels causes systemic iron deficiency (3). Conversely, hepcidin deficiency causes systemic iron overload (1). Several proteins, including HFE (hemochromatosis protein) (4), transferrin receptor 2 (5), hemojuvelin (6), and the transcription factor SMAD4 (7), regulate body iron levels by promoting expression of Hamp, the gene encoding hepcidin. However, the components of a pathway to downregulate Hamp in response to iron deficiency (8) remain poorly understood.

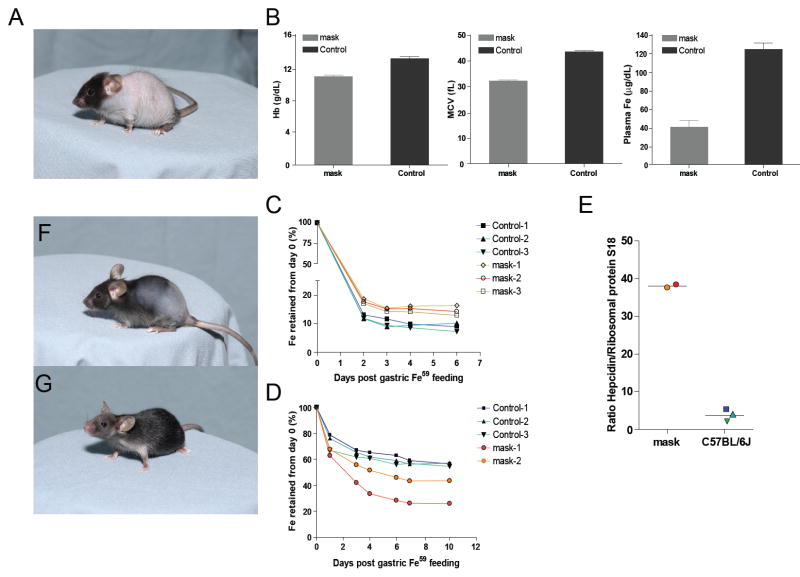

We now report the discovery of a protein with non-redundant function in Hamp suppression, required to permit normal uptake of enteric iron in response to iron depletion and capable of countering all known Hamp-activating stimuli. A phenotype observed among G3 mice (C57BL/6J background) homozygous for mutations induced by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (9), termed Mask, was characterized by gradual loss of body but not facial hair, leading to almost complete nudity of the trunk within about 4 weeks (Fig. 1A). Mask homozygotes are slightly smaller than their heterozygous littermates, and adult female homozygotes are infertile. Male homozygotes retain fertility, as do heterozygotes of both sexes. Mutant mice maintained on a standard laboratory diet manifested microcytic anemia, low plasma iron levels (Fig. 1B), and depleted iron stores (Fig. S1). There was no evidence of occult blood loss. We therefore suspected that intestinal iron absorption might be abnormal and measured the retention of ferrous 59Fe after intragastric administration to mask homozygotes and wildtype controls receiving a standard laboratory diet. Mask mice retained slightly more iron than wildtype animals (Fig. 1C). However, because mask mice were anemic and iron deficient (conditions that favor iron absorption), we repeated the experiment using mask homozygotes and controls that had been maintained on an iron-deficient diet for four weeks. The relationship between mask homozygotes and controls was now reversed (Fig. 1D): iron-deprived but non-anemic control animals showed about a six-fold increase in efficiency of iron absorption, whereas anemic mask homozygotes showed only a 3.5-fold increase in comparison to animals maintained on a standard laboratory diet.

Fig. 1. The mask phenotype.

A. Appearance of mask mice at 4 weeks of age. B. Anemia and iron deficiency in mask homozygotes 6-8 weeks of age. Hemoglobin (Hb), mean red blood cell volume (MCV) and plasma iron levels in mask homozygote and control mice. N=4 for each column. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. C. and D. Retention of radioactive iron administered intragastrically. In C, mice were maintained on a normal diet prior to instillation of iron. In D, mice were iron depleted for one month prior to instillation of iron. E. After measuring retention of 59Fe in iron-depleted mice, hepcidin mRNA levels were measured in the liver of the same five animals, normalized to mRNA levels of ribosomal protein S18. Color coding preserved for individual mice. Re-growth of hair in the mouse shown in panel A, one week (F) and two weeks (G) after initiation of a high-iron diet.

In addition, whereas iron deprivation led to suppression of Hamp transcript levels in the livers of wildtype mice, high Hamp transcript levels were observed in the anemic mask homozygotes (Fig. 1E). This outcome was consistent with insensitivity to low iron stores and consequent failure to suppress Hamp expression. The aberrant upregulation of Hamp transcription occurred despite anemia, which as distinct from iron deficiency alone, normally lowers Hamp transcript levels (8). Both fertility and hair growth (Fig. 1F,G) were consistently restored when mask homozygotes were maintained on an iron-enriched diet (2% carbonyl iron). Hence, the visible phenotype that led to the identification of mask was a consequence of iron deficiency.

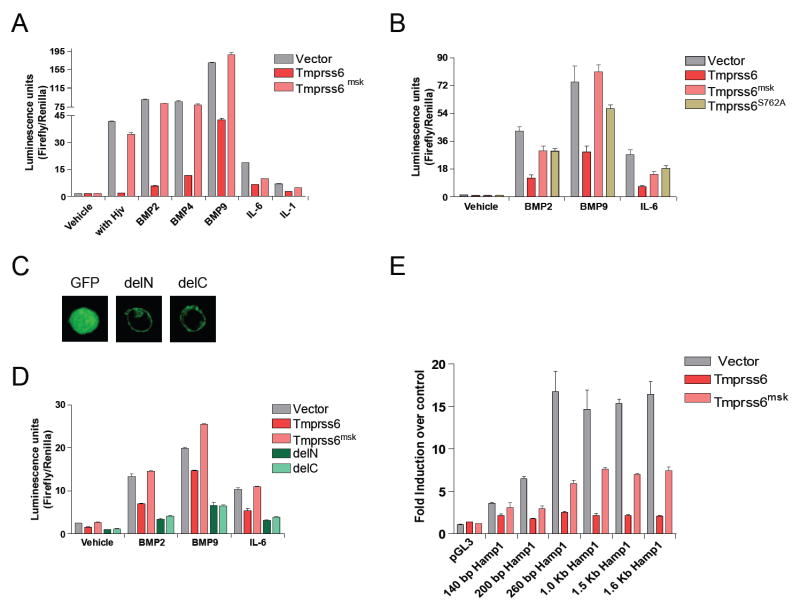

The mutation responsible for the mask phenotype was mapped to distal chromosome 15 and then further confined to a region 1.3 Mbp in size (10). A mutation was identified in Tmprss6, encoding a transmembrane serine protease of unknown function. TMPRSS6 is a type II plasma membrane protein 811 residues in length, also known as matriptase-2 (11). Expression anatomy databases indicate that the Tmprss6 gene is expressed in a limited number of tissues, including the liver and olfactory and vomeronasal epithelium in the mouse (http://symatlas.gnf.org/SymAtlas/ and Fig. S2). In both humans and mice, the major site of TMPRSS6 expression is the liver. TMPRSS6 includes a C-terminal trypsin-like serine protease domain (shown to be extracellular), three class A LDL receptor domains, and two CUB domains (similar to a domain represented in BMP1 as well as C1R and C1S proteins) and a membrane-proximal SEA domain (Fig. 2B). The mask mutation, an A→G transition, eliminates a splice acceptor site upstream from exon 15 (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3). cDNA sequencing showed that two abnormal splice products result from this mutation (Genbank: EU190436, EU190437), both encoding products that would lack the proteolytic domain (Fig. 2B). No normal mRNA product was detectable in homozygous mutants (Fig. S4). We confirmed that the Tmprss6 mutation is responsible for the mask phenotype by BAC transgenesis (Fig. S5 and S6). Introduction of a 197 kb piece of genomic DNA containing the intact Tmprss6 gene and its 5’ and 3’ flanking elements rescued the hair loss phenotype in four of four homozygous mutant mice and rescued anemia and iron deficiency in three of four transgenic mice (Fig. 3) (10).

Fig. 2. The mask mutation.

A. Schematic illustration of the transcripts resulting from the mutated Tmprss6mask allele. The mutation site, at the acceptor splice junction upstream from exon 15, is indicated by black arrowhead; a premature stop codon is predicted as indicated by the asterisk. B. Illustration of the coding change that results from the mutation (SMART diagram).

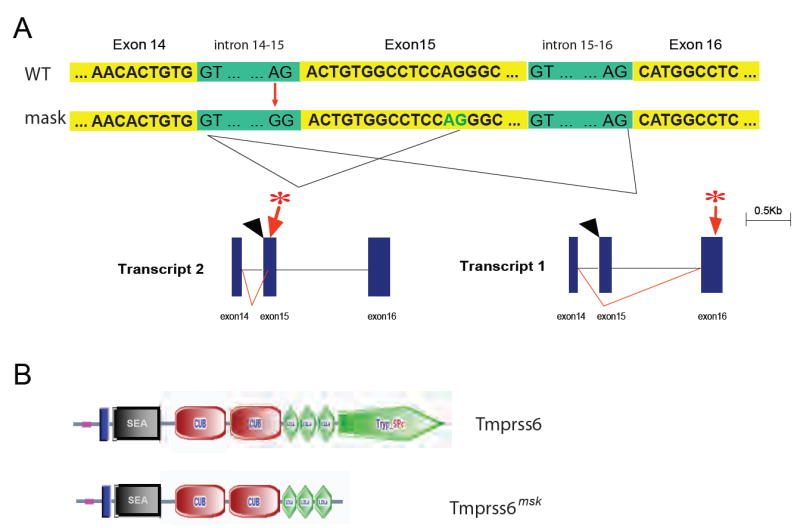

Fig. 3. Rescue of the mask phenotype by BAC transgenesis.

Four founders (designated 49-52 OQ) were produced by microinjecting a BAC clone bearing the WT Tmprss6 sequence into single-cell embryos homozygous for the mask mutation. Hemoglobin and serum iron levels in each of the founders, in blood sampled at 4 weeks of age. B6 controls, age-matched C57BL/6J mice, N=4. Non-transgenic controls, Tmprss6msk/msk littermates that lacked the transgene, N=4. Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

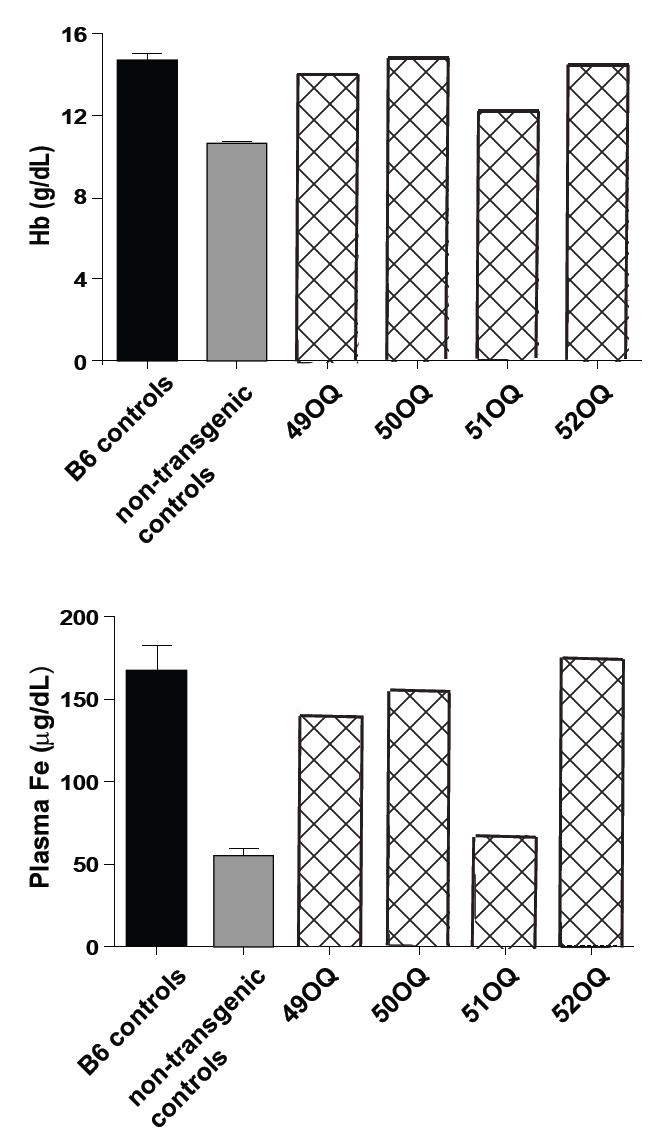

Hamp is upregulated in response to the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 (12) and IL-1 (13) which may collectively mediate the anemia of chronic disease (14). It is also upregulated by the bone morphogenetic proteins, e.g. BMP2, BMP4, and BMP9 (7, 15) and by hemojuvelin (16). Our observation of low iron levels coupled with high Hamp transcript levels in mask mutants suggested that TMPRSS6 might negatively regulate Hamp activation to promote iron uptake. We hypothesized that the intact TMPRSS6 protein, if overexpressed, might prevent induced upregulation of the Hamp promoter. We tested this hypothesis by cotransfecting HepG2 cells with a normalized Hamp reporter construct (17, 18) and cDNAs encoding either wildtype or mask mutant versions of TMPRSS6. Either a cotransfected hemojuvelin- or SMAD1-encoding sequence, or stimulation with IL-1α, IL-6, BMP2, BMP4, or BMP9 was used to induce the Hamp promoter (Fig. 4a and Fig. S7). TMPRSS6 cotransfection strongly inhibited Hamp reporter gene activation by each stimulus whereas the mask mutant version of TMPRSS6 showed at most a modest inhibitory effect. However, the mutant TMPRSS6 appeared to retain some suppressing activity, particularly with respect to its ability to block Hamp promoter responses to IL-1α and IL-6. SMAD1-induced Hamp promoter responses were also blocked by normal (but not truncated) TMPRSS6 (Fig. S7).

Fig. 4. Effect of WT or mask mutant TMPRSS6 expression on Hamp promoter responses.

HepG2 cells were transfected with a full-length Hamp promoter reporter construct in all experiments shown in A-D, and with a normalizing renilla luciferase construct. Tmprss6, full length construct encoding the native protein. Tmprss6msk, the truncated mutant sequence expressed by mask mice. Tmprss6S762A, protease-dead Tmprss6 mutant. delN, GFP cytoplasmic domain, TMPRSS6 transmembrane and ectodomain. delC, GFP ectodomain and TMPRSS6 transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. A. The effect of Tmprss6 and Tmprss6msk on Hamp promoter activity in cells cotransfected with a hemojuvelin-encoding vector or stimulated with BMP2, BMP4, BMP9, IL-6, or IL-1α. B. Comparison of the Hamp promoter-suppressing effects of Tmprss6, Tmprss6msk, and Tmprss6S762A in cells subjected to the stimuli indicated. C. Localization of delN and delC constructs in HepG2 cells by confocal fluorescence microscopy. D. Comparison of the Hamp promoter-suppressing effects of Tmprss6, Tmprss6msk, delN and delC constructs in cells subjected to the stimuli indicated. E. Response of Hamp promoter deletion constructs to induction by IL-6 (length indicated with respect to the cap site), and the relative suppression of responses by co-transfection with Tmprss6 or Tmprss6msk constructs. In all experiments (A-E), duplicate transfections were performed. Incubations with cytokines were performed for 16 hours before luminescence was read to estimate hepcidin promoter activity. Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

We hypothesized that TMPRSS6 participates in a transmembrane signaling pathway triggered by iron deficiency and independent of the known Hamp activation pathways. This putative pathway would ultimately interact with suppressive element(s) in the Hamp promoter, inhibiting expression in response to activating stimuli. To determine whether the proteolytic activity of TMPRSS6 was essential to suppression of Hamp promoter activity, the serine residue of the catalytic triad was mutated to alanine, and the protease-dead mutant was expressed in HepG2 cells together with activating stimuli. The point mutation produced an effect similar to that of the mask truncation, indicating that proteolysis by TMPRSS6 is integral to the Hamp suppression mechanism (Fig. 4B). To address whether TMPRSS6 might signal via its own cytoplasmic domain we designed two additional constructs, termed delN and delC. delN retained the entire TMPRSS6 ectodomain and membrane-spanning domain, but the cytoplasmic domain was replaced with a GFP-encoding sequence. delC consisted of a TMPRSS6 cytoplasmic domain and membrane-spanning domain, but the ectodomain was replaced with a GFP-encoding sequence. Both delN and delC were membrane-expressed proteins, as assessed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4C). When overexpressed, both delN and delC suppressed Hamp promoter activity more strongly than the wildtype construct (Fig. 4D).

Interpreting these results in light of the fact that an endogenous human TMPRSS6 transcript is expressed by HepG2 cells, we infer that: 1. TMPRSS6 is in a signaling pathway that suppresses Hamp expression; 2. the TMRPRSS6 ectodomain represses this signal, just as many receptor ectodomains enforce receptor silence in the absence of a specific ligand (19, 20); and 3. the cytoplasmic domain of TMPRSS6 is integral to signal transduction, since when overexpressed in the absence of the repressive ectodomain, it autonomously drives a Hamp suppression signal. Overexpression of the wildtype protein or the delN construct suppresses Hamp expression and the TMPRSS6 ectodomain is only capable of signaling if it is capable of proteolysis. A model that would account for these observations is presented in Figure S8.

To analyze Hamp promoter responses to activating and inhibitory stimuli, a series of deletion constructs was tested for activation by IL-6 administered to HepG2 cells in the presence or absence of TMPRSS6 overexpression. As little as 140 bp of promoter sequence (upstream from the cap site) supported TMPRSS6-mediated blockade of reporter gene activation. The full activating effect of IL-6 required approximately 260 bp of promoter sequence (Fig. 4E). A proximal repressor element in the Hamp promoter thus mediates inhibition by a TMPRSS6-dependent signal, although it has yet to be determined whether other repressor elements are active within more distal portions of the promoter.

The Tmprss6 locus has not been targeted in mice. TMPRSS6 is known to cleave extracellular matrix proteins (11). However, as demonstrated by the mask phenotype, a major function of this protein is in iron regulation. TMPRSS6-mediated Hamp suppression permits adequate uptake of iron from dietary sources. Without Hamp suppression, severe iron deficiency supervenes despite “normal” dietary iron intake. Hepcidin-mediated restriction of iron absorption operates effectively over a range of iron concentrations encompassing that found in the diet of laboratory mice. However, hepcidin cannot restrict the absorption of supraphysiologic concentrations of iron, which occurs through pathway(s) that permit uptake despite systemic iron overload (21). Thus, mask mutants exhibit dramatic iron deficiency when fed a standard diet but show phenotypic normalization in response to oral administration of 2% carbonyl iron (Fig. 1F, G, and Fig. S9). The mechanism of hair loss in mask homozygotes remains to be established. It is of note that severe iron deficiency is associated with hair loss in humans (22) as it is in mice (23).

It has been suggested that the proteins Hif-1α and growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) participate in the physiologic response to body iron attenuation. Hif-1α is a transcription factor regulated by the iron-dependent prolyl-4-hydroxylase (PHD2) (24), and responds both to low cellular iron concentration and to hypoxia (25-27). GDF15 is a circulating TGF-β superfamily member that suppresses Hamp expression, albeit under conditions of iron overload, in the context of thalassemia (28). Either of these proteins might be elements of the TMPRSS6-dependent pathway as we have described it. However, the genetic evidence presented here demonstrates that neither Hif-1α nor GDF15 supplant the function of TMPRSS6 under standard feeding conditions. We also note that the TMPRSS6-dependent pathway predominates over all known Hamp-activating pathways, since overexpression of TMPRSS6 can nullify in part or in full the hepcidin-inducing effects of hemojuvelin, BMP2/4/9, SMAD1, IL-1, and IL-6.

Because overexpression of TMPRSS6 blocks activation of diverse pathways for upregulation of hepcidin, we anticipate that overexpression or dysregulation of TMPRSS6 might cause iron overload whereas mutational inactivation of TMPRSS6 (as in mask mice) would lower body iron content. From a therapeutic standpoint, TMPRSS6 activation might block cytokine-mediated anemia during chronic disease, and selective antagonism of TMPRSS6 might be utilized in the treatment of systemic iron overload (hemochromatosis). With regard to its olfactory and vomeronasal expression, we suggest that in addition to signaling hepatocytes of iron deficiency, TMPRSS6 may alert olfactory neurons and thereby engender iron-seeking behavior under conditions of iron starvation. Further work will be required to determine whether this is the case.

Supplementary Material

Materials and Methods

Supporting Text

Figures S1 to S9

References

Reference List

- 1.Nemeth E, Ganz T. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006;26:323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nemeth E, et al. Science. 2004;306:2090. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolas G, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072632499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad KA, et al. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;29:361. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawabata H, et al. Blood. 2005;105:376. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papanikolaou G, et al. Nat Genet. 2004;36:77. doi: 10.1038/ng1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang RH, et al. Cell Metab. 2005;2:399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolas G, et al. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1037. doi: 10.1172/JCI15686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 10.See supporting material on Science Online.

- 11.Velasco G, Cal S, Quesada V, Sanchez LM, Lopez-Otin C. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemeth E, et al. Blood. 2003;101:2461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee P, Peng H, Gelbart T, Wang L, Beutler E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409808102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy CN, Andrews NC. Curr Opin Hematol. 2005;12:107. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, Beutler E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603124103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babitt JL, et al. Nat Genet. 2006;38:531. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truksa J, Lee P, Peng H, Flanagan J, Beutler E. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, Beutler E. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazzoni F, Beutler B. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watowich SS, Hilton DJ, Lodish HF. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1994;14:3535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gitlin D, Cruchaud A. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:344. doi: 10.1172/JCI104488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deloche C, et al. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:507. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell ES, McFarland EC, Kent EL. Transplant Proc. 1970;2:144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNeill LA, et al. Mol Biosyst. 2005;1:321. doi: 10.1039/b511249b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peyssonnaux C, et al. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1926. doi: 10.1172/JCI31370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon D, et al. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beutler E. Science. 2004;306:2051. doi: 10.1126/science.1107224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanno T, et al. Nat Med. 2007;13:1096. doi: 10.1038/nm1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.This work was supported by NIH grant numbers AI054523 and DK53505-09 and the Stein Endowment Fund.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Supporting Text

Figures S1 to S9

References