Abstract

Secondary syringe exchange (SSE) refers to the exchange of sterile syringes between injection drug users (IDUs). To date there has been limited examination of SSE in relation to the social networks of IDUs. This study aimed to identify characteristics of drug injecting networks associated with the receipt of syringes through SSE. Active IDUs were recruited from syringe exchange and methadone treatment programs in Montreal, Canada, between April 2004 and January 2005. Information on each participant and on their drug-injecting networks was elicited using a structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire. Subjects’ network characteristics were examined in relation to SSE using regression models with generalized estimating equations. Of 218 participants, 126 were SSE recipients with 186 IDUs in their injecting networks. The 92 non-recipients reported 188 network IDUs. Networks of SSE recipients and non-recipients were similar with regard to network size and demographics of network members. In multivariate analyses adjusted for age and gender, SSE recipients were more likely than non-recipients to self-report being HIV-positive (OR = 3.56 [1.54–8.23]); require or provide help with injecting (OR = 3.74 [2.01–6.95]); have a social network member who is a sexual partner (OR = 1.90 [1.11–3.24]), who currently attends a syringe exchange or methadone program (OR = 2.33 [1.16–4.70]), injects daily (OR = 1.77 [1.11–2.84]), and shares syringes with the subject (OR = 2.24 [1.13–4.46]). SSE is associated with several injection-related risk factors that could be used to help focus public health interventions for risk reduction. Since SSE offers an opportunity for the dissemination of important prevention messages, SSE-based networks should be used to improve public health interventions. This approach can optimize the benefits of SSE while minimizing the potential risks associated with the practice of secondary exchange.

Keywords: HIV, Hepatitis C, Injection drug use, Social network, Secondary syringe exchange, Syringe sharing

INTRODUCTION

The sharing of blood-contaminated drug equipment is the major risk factor for HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among injection drug users (IDUs).1 The distribution of sterile injection equipment has, therefore, been a major focus of harm-reduction programs for IDUs because it is expected that better access to new injecting materials could lower rates of equipment sharing.2–6 In Montreal, Canada, sterile syringes can be obtained from sanctioned sources such as syringe exchange programs (SEPs), outreach workers, or purchased without prescription from selected pharmacies.7 In addition, a minority of injectors also obtain new syringes from their injecting peers who redistribute sterile syringes. This practice has been called secondary syringe exchange (SSE) because it involves secondary exchangers who obtain large quantities of syringes from a sanctioned source to redistribute them to other IDUs for sale, trade, altruistic purposes, or as part of drug transactions.8–12

Of the approximately 44,000 visits recorded to SEP and other syringe access sites in Montreal during 2002–2003, 15% of visits involved the distribution of sterile syringes for use by both the service attender and other IDUs, whereas in 5% of visits, the syringes were destined specifically for another IDU.7 The high volume of syringes distributed through SSE reflects findings from other jurisdictions where SSE providers have been reported to distribute up to 60% of syringes exchanged at SEPs, although these individuals represented less than 10% of the clientele.8,13

Traditional SEP and pharmacy-based syringe distribution strategies have several limitations. The use of SEPs may be restricted by limited hours of operation, distribution policies, geographic distance to the SEP, fear of stigmatization, as well as fear of police harassment.8,9,10,13–15 Pharmacies, on the other hand, may refuse to provide syringes without a prescription, do not typically accept used syringes in exchange for new ones, nor do they offer the social and medical services available at SEPs. In addition, SEPs and pharmacies may serve a selective subpopulation of IDUs. In contrast, SSE represents a mechanism for overcoming the barriers associated with SEPs and pharmacies while improving the coverage of syringe distribution and reducing the circulation of dirty syringes in the community.16 SSE may also provide a gateway for disseminating HIV and HCV prevention messages through individuals who are providers of this service, given that the social networks of IDUs provide an existing infrastructure for peer education as a result of the familiarity of members and their frequent contact with each other.10 Other reported benefits of secondary exchange have included reductions in syringe sharing, less reuse of personal syringes, less filter and container sharing, more consistent condom use, and greater uptake of drug treatment.11–13

However, critics of SSE contend that IDUs who do not personally attend a SEP to obtain their own injecting equipment are not exposed to other important prevention services that may be offered, such as HIV or HCV testing and counseling, behavioral interventions, as well as referrals to drug abuse treatment programs and relevant social services.8 In addition, SSE recipients appear to live within social contexts that can increase the health risks associated with drug using.17 A study of IDUs in Montreal and Vancouver found that SSE participation was associated with borrowing used syringes and drug preparation equipment.18 Another study in Vancouver described several risky behaviors for infection among SSE recipients, such as higher rates of cocaine injecting, injecting in public places, and requiring or providing help to inject another IDU.19 Despite these findings, few studies have considered SSE as a risky practice associated with HIV and HCV infection.

Because there are currently few studies examining SSE, the debate regarding the true benefits of this practice remains unresolved. In particular, one area of inquiry that has not been well addressed pertains to the social network interactions of SSE participants. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate how social network characteristics are associated with SSE, with a focus on the individuals who receive sterile syringes from their injecting peers.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

Active IDUs who injected at least once in the past 6 months were recruited into this cross-sectional study from three of the largest SEPs and two methadone clinics in Montreal, Canada, between April 2004 and January 2005. Methadone subjects were new clients in treatment (median duration of treatment: 2 months). Previous research suggests that while the majority of methadone patients eventually reduce drug use, some continue to inject during the early months of treatment and maintain pre-treatment risk behaviors.20,21 The subsample of IDUs from methadone clinics did not differ significantly from the SEP sample with regard to the drug-use variables examined in this analysis.

The study was part of a larger project aimed at understanding HCV-related psychosocial factors and risk behaviors of IDUs in Montreal. The project was promoted by posting flyers on bulletin boards at recruitment sites, by word of mouth, and by site personnel. Systematic sampling of every second client seeking services at the recruitment sites was used to minimize selection bias. A uniform recruitment strategy was used at all participating sites. Interviews were conducted in a private room on site or arranged at the Montreal Regional Public Health Department whenever appropriate. The rate of refusal could not be calculated because the number of persons approached for participation was not recorded.

Eligibility as an active IDU was verified by the presence of injection marks or through knowledge about community services offered to IDUs and of typical injection procedures. Participants were at least 18 years of age, provided informed consent, and reimbursed CDN $20 for their time. Subjects underwent an anonymous, face-to-face interview administered by trained study interviewers that required, on average, 1.5 h to complete. At the conclusion of the interview, participants were given general information about HCV transmission and infection. All persons approached for participation were offered referrals to community services for IDUs.

The study procedures were approved by the McGill University Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board for Research on Human Subjects.

Data Collection

Information was elicited about participants’ sociodemographics (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, income, housing), drug preparation and injection practices (age at first injection, years injecting, drugs injected, place and frequency of injecting, sharing of drugs, borrowing and lending of injection equipment), self-reported HIV and HCV testing and infection status, self-rated physical and mental health, and risk reduction practices (use of sterile injecting materials, use of community prevention services for IDUs including SEPs and drug treatment, problems with accessing sterile equipment from SEPs, reasons for asking others to obtain sterile equipment from a SEP). Public or semipublic injecting locations were defined as areas without privacy such as the street, cars, parks, public toilets, and abandoned buildings. Private injection settings referred to injections in one’s own home, the home of a friend or family member, or hotel room. All risk behavior variables referred to the past 6 months or 1 month before study enrolment. The 1-month timeframe of risk behavior assessment was used for questions most likely to be affected by recall.

Elicitation of the Social Network

The network questionnaire was modelled on the General Social Survey and the Social Network List designed to capture the effect of social roles on behavior.22,23 Each study participant (also called an index) was asked to anonymously identify up to ten individuals, either IDUs (up to five) or non-IDU, with whom they had significant interaction during the past month. Significant interaction was defined as having more than occasional contact in which the network member played an important role in the subject’s life. Interviewers were trained to use memory enhancing cues to elicit the identification of members, such as providing examples of persons who might represent network members and recent situations or locations where interactions with network members could have occured.24,25

Once the list of network members was generated, participants were asked to characterize each member. Independent variables of interest describing the network included the number of network members and network turnover rate. Network turnover was defined as the proportion of new IDUs in the personal network during the past month relative to the number of members in the past 6 months. Variables describing network members included sociodemographics (age, gender, ethnicity), duration of relationship, HIV and HCV status, and history of injection drug use.

Subjects were asked to classify each of the nominated persons in their personal network to a specific domain defined by their role as (1) a drug injector, (2) sexual partner, (3) sexual client, (4) family member, (5) provider of social support (e.g., close friend, co-worker), (6) drug dealer, (7) acquaintance, or (8) other role. Family members and providers of social support were grouped together as social support network members. A social support member represented a person who could provide advice or help with a personal problem. Sexual partners were regular or casual non-paying partners. IDU network members were individuals who injected with the index with or without sharing drugs or injecting equipment. According to the above groupings, network members could play more than one relational role.

For a network member identified as an IDU, variables of interest included the member’s duration of injecting, type of drugs currently used, usual place of injecting, frequency of injecting, history of attendance at shooting galleries, current use of SEPs or methadone treatment services, proportion of injections with the index, provision of sterile syringes or sterile drug preparation equipment to the index, and frequency of sharing used syringes or drug preparation equipment with the index.

Given the pivotal role of peer injectors in SSE compared to non-injecting network individuals, the former were selected for analysis (six non-IDU persons who supplied sterile syringes were excluded). SSE recipients were defined as IDUs who received sterile syringes from a network member during the past month.

Analysis

Means and medians were calculated for continuous variables. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test, whereas categorical variables were examined with Pearson’s chi-square test. Variables were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Logistic regression was used to calculate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals to examine the association of selected variables with being an SSE recipient in the past month. Variables to be modeled were selected based on prior substantive knowledge presented in the medical literature and on hypothesized associations. Independent variables found to have a p < 0.20 in the bivariate analysis were considered in a multivariate model using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering of network members on the participant.26 The final multivariate model was chosen by examining the change in the quasi-likelihood statistic by sequential removal of variables from a saturated model and comparing the result with a forward entry process.27 Variables significant at p < 0.05 were retained in the model, which was adjusted for age and gender of the index. Interactions of index age and gender with significant covariates were also examined.

RESULTS

Among the 218 participants, a total of 126 were SSE recipients, whereas 92 did not receive syringes through SSE. Overall, participants were predominantly recruited from SEPs (89%), male (72%), Caucasian (92%), and single (88%), with a mean age of 32 years. Based on self-reports, 19% were HIV positive, 64% were HCV positive, and 19% were co-infected with HIV and HCV.

As shown in Table 1, SSE recipients did not differ from non-recipients on personal characteristics except for drug overdose history and several drug use variables (drug solution sharing, requiring or providing help injecting, having multiple injecting partners, and borrowing or lending syringes and drug preparation equipment). Most subjects had been SEP clients during the past 6 months, and few reported problems obtaining sterile injecting equipment from an SEP.

TABLE 1.

Study sample characteristics of IDUs (n = 218) in Montreal, Canada, contrasting recipients and non-recipients of sterile injecting materials through secondary syringe exchange

| SSE recipients (n = 126) | SSE non-recipients (n = 92) | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age (mean, range) | 31.6 | (17.9–54.6) | 33.4 | (18.7–52.4) | 0.43 | |

| Gender | Male | 85 | (69.7) | 68 | (73.9) | 0.50 |

| Female | 37 | (30.3) | 24 | (26.1) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 109 | (89.3) | 80 | (87.0) | 0.79 |

| Married/common law | 6 | (4.9) | 5 | (5.4) | ||

| Widowed, divorced, separated | 7 | (5.8) | 7 | (7.7) | ||

| Education | ≤High school | 87 | (71.9) | 73 | (79.3) | 0.21 |

| >High school | 34 | (28.1) | 19 | (20.7) | ||

| Income | <$20,000 | 89 | (73.0) | 74 | (80.4) | 0.20 |

| ≥$20,000 | 33 | (27.0) | 18 | (19.6) | ||

| Housing | Unstable | 48 | (39.7) | 45 | (48.9) | 0.18 |

| Stable | 73 | (60.3) | 47 | (51.1) | ||

| Health status | ||||||

| Self-reported HIV-positive | 27 | (24.1) | 12 | (14.6) | 0.10 | |

| Self-reported HCV-positive | 67 | (63.2) | 48 | (61.5) | 0.82 | |

| Accidental drug overdose (past year) | 31 | (25.4) | 12 | (13.0) | 0.03 | |

| Poor self-rated physical health | 7 | (5.7) | 5 | (5.5) | 0.94 | |

| Poor self-rated mental health | 12 | (9.8) | 5 | (5.5) | 0.25 | |

| Drug use | ||||||

| Years injecting (mean, range) | 11.8 | (0.2–36) | 12.0 | (0.8–34) | 0.53 | |

| Frequency of injectinga | Daily | 55 | (45.1) | 31 | (36.9) | 0.24 |

| <Daily | 67 | (54.9) | 53 | (63.1) | ||

| Drug solution sharinga | 95 | (77.9) | 49 | (53.3) | <0.001 | |

| Require or provide help injectinga | 76 | (62.3) | 31 | (33.7) | <0.001 | |

| Injecting alonea | Yes | 2 | (1.6) | 11 | (13.1) | 0.001 |

| No | 120 | (98.4) | 73 | (86.9) | ||

| Drug most commonly injectedb | Cocaine | 85 | (78.7) | 63 | (82.9) | 0.48 |

| Heroin | 23 | (21.3) | 13 | (17.1) | ||

| Polydrug useb | 78 | (63.9) | 51 | (55.4) | 0.21 | |

| Place of injectinga | Public/semipublic | 46 | (45.1) | 26 | (37.1) | 0.30 |

| Private | 56 | (54.9) | 44 | (62.9) | ||

| Borrowing equipmentb | Syringes | 37 | (30.3) | 16 | (17.4) | 0.03 |

| Drug preparation equipment | 68 | (55.7) | 31 | (33.7) | 0.001 | |

| Lending equipmentb | Syringes | 33 | (27.0) | 12 | (13.0) | 0.01 |

| Drug preparation equipment | 60 | (49.2) | 27 | (29.3) | 0.003 | |

| Client of a SEPb | 115 | (96.6) | 89 | (98.9) | 0.29 | |

| Problems obtaining sterile equipment from SEPb | 20 | (16.4) | 11 | (12.2) | 0.40 | |

Percentage among all non-missing responses; p value associated with chi-square test or Student’s t test.

aRefers to past month.

bRefers to past 6 months.

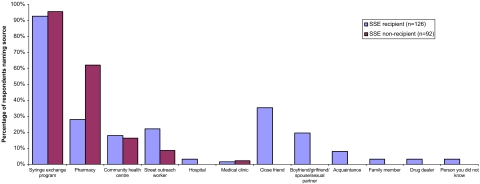

A substantial proportion of SSE recipients named close friends (35%), sexual partners (20%), and other individuals in their injecting network as sources of new syringes (Figure 1). Nearly twice as many non-recipients than SSE recipients obtained their sterile syringes from pharmacies. Among 80 participants who responded to a query about the reasons for asking someone else to obtain syringes from an SEP, the most commonly cited issues were convenience (62%), being unable to personally attend an SEP because of their drug-related physical or mental state and/or problems with transportation (33%), or fear of harassment or stigmatization from going to an SEP (5%).

FIGURE 1.

Sources of sterile syringes of SSE recipients and non-recipients in the past 6 months. Subjects may respond in more than one category.

The injecting networks of participants consisted of 374 network members; SSE recipients identified 186 network members, whereas SSE non-recipients nominated 188 individuals. The injecting networks of SSE recipients compared to non-recipients differed on several aspects (Table 2). SSE recipients had a significantly higher turnover of members within their personal networks. Network members of SSE recipients were also more likely to be sexual partners, HIV positive, inject daily, and share syringes and drug preparation equipment with the index during the month before study enrolment compared to the members of SSE non-recipients (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of drug injecting networks of SSE recipients and non-recipients who identified a total of 374 network members

| Networks of SSE recipients (n = 186 members) | Networks of SSE non-recipients (n = 188 members) | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Network structural characteristics | ||||||

| IDU network size (#members per egocentric network), mean (range) | 2.42 | (1–6) | 2.73 | (1–6) | 0.27 | |

| Network turnover, mean (SD) | 0.35 | (0.33) | 0.25 | (0.31) | <0.001 | |

| Network member characteristics | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 129 | (70.9) | 121 | (66.9) | 0.41 |

| Female | 53 | (29.1) | 60 | (33.1) | ||

| Age (years), mean (range) | 31.1 | (16–50) | 30.0 | (18–60) | 0.11 | |

| Role of network member | Social support | 75 | (40.3) | 80 | (42.6) | 0.66 |

| Sexual partners | 56 | (30.1) | 38 | (20.2) | 0.03 | |

| HIV-positive | 46 | (34.8) | 23 | (21.5) | 0.02 | |

| HCV-positive | 84 | (63.2) | 83 | (69.2) | 0.31 | |

| Drug most commonly injected | Cocaine | 151 | (83.4) | 152 | (84.0) | 0.89 |

| Heroin | 30 | (16.6) | 29 | (16.0) | ||

| Duration of relationship (years), median (IQR) | 3.0 | (1.0–20.0) | 2.0 | (0.9–18.0) | 0.34 | |

| Years injecting Median (IQR) | 5.0 | (3.0–21.0) | 5.0 | (2.5–26.0) | 0.15 | |

| Frequency of injecting | Daily | 116 | (64.8) | 73 | (42.9) | <0.001 |

| <Daily | 63 | (35.2) | 97 | (57.1) | ||

| Ever attended a shooting gallery | 74 | (55.6) | 65 | (52.4) | 0.61 | |

| Current uses SEP or methadone program | 161 | (89.4) | 150 | (82.9) | 0.07 | |

| Shared injecting equipment with index | Syringes | 64 | (34.4) | 24 | (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Drug preparation equipment | 99 | (53.2) | 49 | (26.1) | <0.001 | |

Percentage among all non-missing responses; variables refer to past month unless stated otherwise. p Value associated with chi-square test or Student’s t test. Turnover rate represents the proportion of new injectors in network in past month relative to the number of members in past 6 months.

IQR Interquartile range.

In the multivariate model combining personal and network characteristics (Table 3), SSE recipients were at higher odds of being HIV positive by self-report and requiring or providing help with injecting. With regard to their networks, SSE recipients were more likely to have a drug injecting network member who is also a sexual partner, who currently uses an SEP or methadone program, injects daily, and shares syringes with the index. Of note, females constituted the largest proportion of sex partner providers of sterile syringes. Although sexual partners were at greater odds of participating in SSE, we found no significant interaction of partner role with the age or gender of the index. Similarly, an examination of network member’s age, injecting frequency, and syringe sharing practice showed no interaction with the age or gender of the index.

TABLE 3.

Results of GEE regression analysis of personal and drug injecting network characteristics associated with being an SSE recipient

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Self-reported HIV-positive status | 3.56 (1.54–8.23) |

| Required or provided help with injecting | 3.74 (2.01–6.95) |

| Network | |

| Is a sexual partner | 1.90 (1.11–3.24) |

| Current use of SEP or methadone program | 2.33 (1.16–4.70) |

| Daily injecting | 1.77 (1.11–2.84) |

| Shared syringes with index | 2.24 (1.13–4.46) |

Results based on 310 (of 374) injecting partnerships with non-missing data for variables in the final model. Adjusted for age and gender of index. Variables tested but not significant: personal income, housing, self-reported HIV-positive, overdose in past year, injecting alone, shared drug solution; network-turnover rate, age of member, years injecting, and shared drug preparation equipment with index.

OR Odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

This study found that some SSE relationships involve close drug-using partnerships in which risk reduction practices exist alongside potential risky behaviors for HIV and HCV infection. Although access to sterile syringes through secondary exchange may be benefiting IDUs who require them, the finding of several risk factors for bloodborne virus infections, including the sharing of used syringes within SSE relationships, is of concern.

At the personal level, the association of SSE and HIV-positive status suggests that sterile syringes could be exchanged with risk reduction in mind; the same association was not observed for HCV status. The lack of relationship with HCV infection status could be reflective of a lower perception of HCV infection risk among IDUs or apathy regarding infection risk caused by a feeling of inevitability of infection through continued drug use.28,29 The greater probability of SSE among injectors who require help injecting is suggestive of communal injecting, which favors the sharing of syringes and other drug equipment.30

With regard to drug injecting networks, the current study provides a profile of the networks of SSE recipients. In this predominantly cocaine-injecting population, daily injectors are likely to be in frequent contact with prevention services for the purpose of obtaining sterile injecting equipment, which they may subsequently pass onto their peers. The profile of SSE providers suggests that they are exposed to prevention services by virtue of links with community-based harm reduction services, whereby up to 89% of SSE providers were reported to be currently using SEPs or drug treatment programs. Most research confirms that SSE occurs more frequently within established injecting networks, such as among close friends, sexual partners, and family members.10,13 Furthermore, IDUs with larger injecting networks, those living in close proximity to each other, and those who exchange drugs have also been found to participate in SSE.13,31 An Australian study showed the importance of one’s personal network as a source of injecting equipment, both used and clean.17 In that study, 48% of equipment was obtained from friends, 32% from drug dealers, 10% from acquaintances, and 10% from intimate partners. These findings closely resemble our results of close friends and sexual partners as the most frequent sources of injecting materials. However, the often-close injecting relationships between SSE participants may entail mutual risk behaviors, given that established injecting partnerships have been strongly associated with syringe and drug paraphernalia sharing.32 The motivation for sharing syringes in the context of SSE is an area that requires further investigation. We suspect that sterile syringe exchange may not occur consistently between SSE providers and recipients. A lack of available sterile materials during injecting may require used materials to be shared rather than postponing the injecting episode. Second, there could be reciprocity in the exchange of both sterile and non-sterile injecting materials between injecting partners as a matter of habit within established injecting partnerships.

In general, it has been suggested that among SEP users, SSE participants have similar risk reduction profiles as non-participants of SSE.13 In our sample, SSE non-recipients obtained a larger proportion of their sterile syringes from pharmacies compared to SSE recipients, suggesting that the former may represent a more stable group of IDUs. SSE recipients, on the other hand, relied more on street outreach workers than non-recipients. Indeed, it is possible that non-frequent SEP users may develop social connections for alternate sources of needles and, therefore, do not have more difficulty obtaining needles compared to frequent SEP users.33

Limitations

These results must be considered in light of several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not account for changing social network structure over time, whereby membership of current social networks is different from past networks with regard to SSE. Also, the results might not be generalizable to non-street drug injectors because the sample consisted mainly of SEP-recruited individuals whose risk profile is likely different from other IDUs. Second, because the data were based on proxy reports of network SSE providers, we could not ascertain the original source of syringes, whether exchanged syringes were indeed sterile, and the size of exchange networks (although one study suggested that SSE typically involves between two and ten recipients10). We also recognize that SSE recipients in this study may themselves have been providers of new syringes to other IDUs. Finally, the accuracy of proxy reports by IDUs about their social network members has previously been questioned, but some studies indicate that reports of drug use behaviors have acceptable validity and reliability.34,35

Implications

IDU networks seem to facilitate the distribution of sterile syringes to IDUs who are at-risk of bloodborne infections. However, it is not clear that the current practice of SSE as it exists alongside the sharing of used equipment and other injection-related risk factors will have the desired impact on reducing rates of HIV or HCV infection. Considering that sharing of equipment still occurs, the quantity of clean syringes and other equipment may be insufficient, especially for injectors who inject frequently.

While there are currently no caps on the number of syringes that can be acquired through SEPs in Montreal, there is also no consistent practice across SEPs regarding the use of SSE as a sanctioned risk-reduction strategy. All SEPs continue to encourage in-person acquisition of sterile syringes and drug preparation equipment. A recent report estimates a large shortfall in the uptake of sterile syringes, whereby, only 6.6% of the number of new syringes that were needed was actually acquired.36 The continued sharing of syringes and drug preparation equipment, despite the availability of sterile injecting materials, suggests that social relationships are as important as access to sterile injecting equipment in the practice of sharing injecting equipment. Moreover, it is hypothesized that the co-existence of sharing and SSE is reflective of the entrenchment of drug-using relationships in injecting behaviors that resist change.

While it is important to develop a syringe distribution policy that accommodates secondary exchange along with other models of syringe delivery (e.g., fixed and satellite sites, mobile distribution, peer-based, pharmacies), the additional prevention services that accompany SSE require targeting at the network level. SSE should not be discouraged but rather developed in a way to encourage in-person SEP attendance while concomitantly using SSE networks more effectively for disseminating prevention messages, building skills, and creating norms of safer injecting in their personal networks. Interventions could include training SEP clients as peer mentors to teach safer injection practices to their injecting partners or by encouraging clients to bring their injecting network members to SEPs. Finally, there is a need for further research on the context of using re-distributed syringes so as to understand the interplay between risk enhancing and risk reducing behaviors as they co-exist within injecting partnerships.

Conclusion

The study found overlapping risks and benefits of SSE participation. Because SSE offers an opportunity for the dissemination of important prevention messages, SSE-based networks should be used to focus and improve public health interventions. This approach can optimize the benefits of SSE while minimizing the potential risks associated with the practice of secondary exchange.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Carole Morissette and Pascale Leclerc for the data on sterile syringe distribution in Montreal. The authors are grateful to the study participants, study personnel, and the collaborating recruitment sites (CACTUS-Montréal, Spectre de rue, Relais Méthadone, Dopamine, Herzl Family Practice–Jewish General Hospital).

This study was supported by the Health Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Research Initiative on Hepatitis C and by the Montreal Public Health Department. Prithwish De was supported by a CIHR Doctoral Award and by the CIHR Transdisciplinary Training Program in Population and Public Health Research of Quebec. Robert Platt was supported by a Chercheur–Boursier award from the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Parts of this paper were presented at the International Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm, Vancouver, Canada, April 2006.

Conflict of interest This paper presents no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(8):556–562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Vlahov D, Des Jarlais DC, Goosby E, et al. Needle exchange programs for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection: epidemiology and policy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12 Suppl):S70–S77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Friedmann P, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1992–1997: evidence for a declining epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(3):352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gibson DR, Flynn NM, Perales D. Effectiveness of syringe exchange programs in reducing HIV risk behavior and HIV seroconversion among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2001;15(11):1329–1341. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hurley SF, Jolley DJ, Kaldor JM. Effectiveness of needle-exchange programmes for prevention of HIV infection. Lancet. 1997;349(9068):1797–1800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bastos FI, Strathdee SA. Evaluating effectiveness of syringe exchange programmes: current issues and future prospects. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(12):1771–1782. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Morissette C, Leclerc P, Tremblay C. Monitorage des programmes d’accès au matériel stérile d’injection de Montréal-Centre. Rapport synthèse des principales données recueillies entre avril 1999 et mars 2004. Agence de développement de réseaux locaux de services de santé et de services sociaux; June 2004.

- 8.Bluthenthal RN, Malik MR, Grau LE, Singer M, Marshall P, Heimer R. Diffusion of benefit through Syringe Exchange Study Team. Sterile syringe access conditions and variations in HIV risk among drug injectors in three cities. Addiction. 2004;99(9):1136–1146. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Valente TW, Foreman RK, Junge B, Vlahov D. Satellite exchange in the Baltimore Needle Exchange Program. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(Suppl 1):90–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Snead J, Downing M, Lorvick J, et al. Secondary syringe exchange among injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2003;80(2):330–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Huo D, Bailey SL, Hershow RC, Ouellet L. Drug use and HIV risk practices of secondary and primary needle exchange users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(2):170–184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sears C, Guydish JR, Weltzien EK, Lum PJ. Investigation of a secondary syringe exchange program for homeless young adult injection drug users in San Francisco, California, U.S.A. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27(2):193–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Murphy S, Kelley MS, Lune H. The health benefits of secondary syringe exchange. J Drug Issues. 2004;34(2):245–268.

- 14.Riehman KS, Kral AH, Anderson R, Flynn N, Bluthenthal RN. Sexual relationships, secondary syringe exchange, and gender differences in HIV risk among drug injectors. J Urban Health. 2004;81(2):249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Anderson R, Clancy L, Flynn N, Kral A, Bluthenthal R. Delivering syringe exchange services through “satellite exchangers”: the Sacramento Area Needle Exchange, USA. Intl J Drug Policy. 2003;14(5/6):461–463. [DOI]

- 16.Valente TW, Foreman RK, Junge B, Vlahov D. Needle-exchange participation, effectiveness, and policy: syringe relay, gender, and the paradox of public health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):340–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bryant J, Treloar C. Risk practices and other characteristics of injecting drug users who obtain injecting equipment from pharmacies and personal networks. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17(5):418–424. [DOI]

- 18.Tyndall MW, Bruneau J, Brogly S, Spittal P, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Satellite needle distribution among injection drug users: policy and practice in two Canadian cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(1):98–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, et al. Factors associated with persistent high-risk syringe sharing in the presence of an established needle exchange programme. AIDS. 2002;16(6):941–943. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(3):253–263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hartel DM, Schoenbaum EE, Selwyn PA, Friedland GH, Klein RS, Drucker E. Patterns of heroin, cocaine and speedball injection among Bronx (USA) methadone maintenance patients: 1978–1988. Addiction Research. 1997;8:394–404.

- 22.Burt RS. Network items and the General Social Survey. Soc Networks. 1984;6:293–339. [DOI]

- 23.Hirsch BJ. Psychological dimensions of social networks: a multi-method analysis. Am J Community Psychol. 1979;7:263–277. [DOI]

- 24.Friedman SR, Chapman TF, Perlis TE, et al. Similarities and differences by race/ethnicity in changes of HIV seroprevalence and related behaviors among drug injectors in New York City, 1991–1996. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;22(1):83–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Brewer DD. Forgetting in the recall-based elicitation of personal and social networks. Soc Netw. 2000;22(1):29–43. [DOI]

- 26.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [DOI]

- 27.Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–125. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Cox J, Morissette C, De P, et al. Access to sterile injecting equipment is more important than awareness of HCV status for injection risk behaviours among drug users. Subst Use Misuse. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Hagan H, Campbell J, Thiede H, et al. Self-reported hepatitis C virus antibody status and risk behavior in young injectors. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(6):710–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.O’Connell JM, Kerr T, Li K, et al. Requiring help injecting independently predicts incident HIV infection among injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(1):83–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Latkin C, Hua W, Davey MA, Sherman SG. Direct and indirect acquisition of syringes from syringe exchange programmes in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Intl J Drug Policy. 2003;14(5/6):449–451. [DOI]

- 32.De P, Cox J, Boivin JF, Platt RW, Jolly A. The importance of social networks in their association to drug equipment sharing among injection drug users: a review. Addiction. (In Press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Archibald CP, Ofner M, Strathdee SA, et al. Factors associated with frequent needle exchange program attendance in injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;17(2):160–166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Goldstein MF, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Ildefonso G, Curtis R. Self-reports of HIV risk behavior by injecting drug users: are they reliable? Addiction. 1995;90(8):1097–1104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Jennings KD, Stagg V, Pallay A. Assessing support networks: stability and evidence for convergent and divergent validity. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16(6):793–809. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Leclerc P, Morissette C, Tremblay C. Le matériel stérile d’injection: combine faut-il en distribuer pour répondre aux besoins des UDI de Montréal? Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal; July 2006.