Abstract

The purpose of this grounded theory study was to describe and understand contemporary childbearing women's perceptions of the role of childbirth education in preparing for birth. Participants were interviewed three times: prior to beginning classes, at the end of classes, and within 2 weeks after giving birth. Constant comparative analysis of the data was concurrent with data collection. The core process that emerged was “Negotiating the Journey,” with supporting categories of “Exploring the Unknown,” “Making It Real,” and “Sensing the Readiness.” The findings indicated that, for contemporary women, the value of childbirth education may not be in affecting physiological birth outcomes but rather in helping them to be ready for childbirth and, thereby, completing an important developmental milestone.

Keywords: childbirth education, pregnancy, childbirth, grounded theory, qualitative research

During its early years and continuing throughout the 1980s, childbirth education primarily focused on methods of “natural childbirth” (Bradley, 1965; Dick-Read, 1944; Lamaze, 1970). Since then, the health-care milieu has changed, technology has increased, and expectant parents' motivations for attending childbirth education classes have appeared to change (Martell, 2006). Yet, childbirth education's popularity continues, is often considered a standard of care (Enkin, Keirse, Renfrew, & Neilson, 1999), and is included as an objective in Healthy People 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Nevertheless, an abundance of childbirth education research has not demonstrated strong evidence to support how participation in classes affects the experience of childbirth (Gagnon, 2004; Humenick, 2000; Jones, 1983; Koehn, 2002; Spiby, Slade, Escott, Henderson, & Fraser, 2003). Further findings from the literature indicate that classes continue to be structured from the perspective of the educator rather than from the assessed needs of the participants (Enkin et al, 1999; Nichols & Gennaro, 2000; Nolan, 1997, 1999). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explain and understand contemporary women's perceptions and experiences of childbirth education classes.

Prior to the 1990s, investigators focused on researcher-identified outcomes of childbirth education, primarily physiological outcomes (Jones, 1983). Beginning in the early 1990s, a few descriptive studies of women's perceptions began to appear in the literature. Women reported wanting information on labor and birth (Koehn, 1992); on nursing care, breathing, medications, support, and control (Slaninka, Galbraith, Strzelecki, & Cockroft, 1996; Stamler, 1998); and on nutrition, fetal growth and development, infant care, and feeding (Beger & Beaman, 1996). Women also reported attending classes because their health-care provider invited them, because they wanted their husbands to participate, and because attending childbirth education classes was “normal” (Hallgren, Kihlgren, Norberg, & Forslin, 1995; Stamler, 1998).

Other investigators asked participants to rate the content that was offered. In one study, participants expressed interest in all of the topics; however, they were not asked if the topics met their needs (Sims-Jones, Graham, Crowe, Nigro, & McLean, 1998). Beger and Beaman's (1996) survey of 134 class participants demonstrated a difference between participants' ratings of the content and that of the educators. Expectant parents gave high ratings to the infant-care content, but educators gave high ratings to the tour and role-play. Sullivan (1993) reported that women wanted to select the information they needed rather than participating in a series of predetermined classes. Overall, previous studies primarily investigated mother/parent needs or their ratings of class content. Little is known regarding contemporary childbearing women's perceptions of childbirth education classes.

METHODS

Grounded theory, an inductive approach, was particularly suited for the present study to explain how women interpret formal childbirth education in the process of preparing for childbirth. Specifically, Glaser's (1978, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) grounded theory methods were followed. Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to data collection.

The study was conducted in urban and rural settings within a 60-mile radius in south-central Kansas. Initial recruitment began at two OB-GYN office sites. As data collection progressed, snowball sampling was added. Participants of varying ages and from varying sites were sought in order to confirm and disconfirm developing concepts. Sampling continued until saturation was reached.

Primarily, data collection consisted of audiotaped interviews with open-ended questions. All of the participants were interviewed three times, lasting 30–90 minutes: prior to beginning classes, after the fifth class in the series, and within 2 weeks after the birth of their infant. All interviews occurred outside of the class setting, with most interviews taking place in the participants' homes and two conducted in the conference room of a physician's office.

The interviews were taped, and the initial guiding question was, “Tell me about the reasons you have for choosing to go to childbirth education classes.” The second interview began with, “Tell me about your experiences with being in class.” A beginning question for the third interview was, “Tell me about your birth.” One final question was asked at the conclusion of the third interview: “What specific message would you like to give to childbirth instructors?” A professional transcriptionist transcribed the tapes, verbatim.

Additional sources of data included a review of class materials as well as 35 observation hours of childbirth preparation classes, breastfeeding classes, cesarean classes, infant-care classes, and television programs that were frequently viewed by the participants.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by constant comparative analysis (Glaser, 1978). This process entailed using substantive coding, which involves open coding followed by selective coding to conceptualize the data. Theoretical coding followed in order to conceptualize how the substantive codes related to each other as relational statements. The researcher read and reread the transcripts for verification and saturation. QSR NUD*IST–N6 (Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty. Ltd., 1997) computer software was used to facilitate coding and categorizing the data. As data collection and analysis progressed, a simultaneous review of the literature supported the theoretical conclusions. All data analysis was conducted with methodological consultation from an experienced qualitative researcher.

Establishing Trustworthiness

Lincoln and Guba's (1985) criteria for naturalistic inquiry were used to establish trustworthiness. Data were collected over a period of 7 months, with each participant interviewed three times. Thirty-five hours of observation throughout the data collection/analysis process provided depth to the interviews. Document review was an additional source of data collection. Peer debriefing was conducted after the first two interviews and intermittently, as needed, throughout the remainder of the study. Finally, the processes of member checks involved having selected participants verify the analytic categories, interpretations, and conclusions. The detailed descriptions of the findings provide the evidence for transferability. To establish dependability and confirmability, the researcher retained all records of data collection and analysis.

RESULTS

The sample ultimately consisted of nine pregnant women (aged 22 to 37 years; mean 26.3 years). All of the participants were pregnant women who had previously never attended childbirth education classes. Eight participants were gravida 1, para 0; one was gravida 2, para 0. All of the participants were married, Caucasian, spoke English, and had completed at least some college. Although homogeneous, the sample was characteristic of the childbirth education attendees reported in the literature (Koehn, 2002; Nichols & Gennaro, 2000; Sims-Jones et al., 1998; Spiby et al., 2003; Stamler, 1998) and in the researcher's setting.

All but one of the participants attended a six-class series on childbirth preparation. All of the classes followed a similar pattern for labor and birth education, with variation in areas of infant care, postpartum care, and breastfeeding. All participants planned to breastfeed, but four did not attend specific breastfeeding classes. One stated that she “forgot” to go on the scheduled day, but the others expressed less need or interest. For example, one of these women stated, “I don't know if I'm going to go to that because I feel like you're more—have hands-on learning. Like it would be better to have somebody telling me when you're doing it.” The one participant who did not attend a six-series class (aged 37 years) was scheduled for a cesarean birth. She had made arrangements to attend only the class session that covered cesarean birth but attended all other prenatal classes that the facility offered.

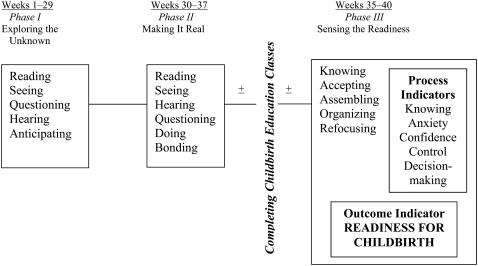

From the beginning, it was clear that childbirth education classes, although a separate entity, were contextually situated in the larger process of transitioning to motherhood. Thus, “Negotiating the Journey” emerged as the underlying basic social psychological process in this larger process (see Figure). The following phases emerged: “Exploring the Unknown,” “Making It Real,” and “Sensing the Readiness.”

Negotiating the Journey

Negotiating the Journey

Negotiating the Journey is defined as the process of moving through an unknown pregnancy experience, with childbirth education classes as a critical part of transitioning to motherhood. The concept of a journey to a destination emerged from the women's expressions of wanting to know “how to have a baby” and “…the fact that I have to be a mom—that kind of weirds me out more than anything else, that I'm going to be somebody's mom” (Participant [P] #5). Further expressions of the need to find their way to a destination included, “I don't know what kind of person I'm going to be as a new mom” (P #1) and “I guess I just want to know all the choices…you know, and since there are so many, and then how to make sure that the things you choose happen when you get there” (P #2). Others described the process of negotiating when they said, “It's kind of hard to sometimes sort it out almost, so…” (P #2) and “I'm hoping for somebody with a lot of options…someone that brings in the platter and says you can have A, B, C, D” (P #8). Another woman expressed it this way:

Exploring the Unknown

The first phase, Exploring the Unknown, relates to activities during the first two trimesters of pregnancy to build a knowledge base about the childbirth process. Clearly, all of the women had already been involved in seeking information about pregnancy, labor, and birth as they shared how they had read, questioned, listened to, and sought information on birth. Yet, the women repeatedly expressed their lack of knowledge. Most of the women reported that they had been encouraged to go to classes by their health-care practitioners, family, or friends but also expressed “it's the thing to do when you are pregnant.”

Several women referred to the “fear of the unknown.” In particular, pain was one of the “unknowns” for which they wanted information. They were more concerned with what options were available to help them manage the pain, rather than “going natural.” Another frequently stated unknown factor was that of the hospital setting. “Going on the tour” (P #4, #6, and #8) was an important expectation of classes. As one participant explained, “It's like when you take a test you like to go…sometimes it's better to go and sit in the seat that you're going to take the test in” (P #8).

Making It Real

The second phase, Making It Real, is identified as participation in childbirth education classes for the purpose of defining and clarifying the task of childbearing. “So now it's real” was the central theme that emerged as the women talked about their experiences in the classes. The women were no longer saying, “I just need to know,” as they had prior to beginning classes. Rather, they spoke in terms of “so now I know” (P #4) and “…and then it was all more clear” (P #5). As one woman put it, “…very realistic views. There was no sugar-coating it” (P #1). Another woman said:

There's so much—just like there are so many extra products you can buy for a kid, there's so much extra information that whether you know it or not, it's not going to help…this is the bare bones, this is how you're going to do it. I thought that was very helpful. (P #2)

The women also discussed the change in their relationship with their husbands. Prior to classes, all of the women had expressed the need for their husbands to learn how to help them through labor. They now described a husband-wife bonding that they had not expected to occur. When asked what was the most important thing that she had learned in class, one of the women replied, “Honestly, I don't really think it has anything to do with Lamaze or any of that. I think it probably has to do with my relationship with [my husband]” (P #1). Another said, “My husband has got way more involved in it than I ever thought he would” (P #7). This was a typical response of all of the women. Overall, there was consensus among the women that classes were helpful, especially for making the approaching birth real.

Sensing the Readiness

During this final phase, all but one woman (who did not complete the class series due to her impending induction) expressed that they were prepared and ready to go. When asked to define or explain “prepared” or “ready,” they had to stop and think before answering. They knew they were ready, but it was not easy to articulate what they meant. However, as the women spoke, indicators of readiness emerged: knowing, decreased anxiety, confidence, control, and decision-making.

The concept of knowing emerged as highly important for sensing readiness. The 37-year-old woman stated it this way, “…being equipped—with things, with information, with proper expectations or realistic expectations…it's the knowing.” Another said:

Well, they've helped in as far as explaining the technical side of birth and the different phases. And understanding in, you know, approximately how long each phase can last and then what you can expect at each phase and when to expect to go to the hospital and then what to expect at the hospital, hopefully, to some extent. And also giving us different options when we're at the hospital. (P #8)

The knowing decreased their anxiety and fostered a sense of confidence. Prior to classes, there was tension and a sense of the women's discomfort associated with not knowing what was going to happen to them. At the conclusion of the classes, a sense of serenity emerged in their body language and in their voices: “I think I just kind of…now I know what to expect and some of the unexpected things, you know, so you're not going, ‘What’s Pitocin' or ‘Why do I have it?’ or all this stuff, you know” (P #3). Another woman stated:

Because, you know, I know it's going to happen…well, it's inevitably going to happen, but now I know what to look for and I think when I first talked to you I had a lot of anxiety and now I'm not really that worried about it. I think I will be fine. (P #2)

Initially, the women expressed their fear of pain and referred to women who “went natural” as brave and did not know how “they did it.” The only way they saw to get “through it” was to have an epidural as soon as they could have it. After the classes, most still thought they might need the epidural at some point, but they wanted to “wait and see” how things would go. One of the women expressed confidence with these words: “…it's going to be painful, but, you know…at most, you know, 24 hard hours, whoopty-do. I can do that” (P #1). Another said, “I think it brings out more of, just shows your abilities and what you're capable of doing” (P #7).

Although the women had accepted that some things were out of their control, they still expressed the need for control and the ability to make their own decisions. They were quite clear about that: “…I mean, I know what I want in labor and what I don't want for the most part…” (P #4) and “I have to be in control” (P #5). To facilitate control and decision-making, by the end of classes, all of the women had either finished or were working on writing a birth plan. They viewed the birth plan as a communication tool as well as a tool to help them sort through all of the options presented to them. One of the women provided a succinct description of how classes contributed to control and decision-making: “…hopefully, giving us the sense of more control over the setting that we're in as far as you can get up and move around, you can do this, you can ask for this. You know, hopefully just empowering us” (P #8).

Although the women had accepted that some things were out of their control, they still expressed the need for control and the ability to make their own decisions.

Finally, the women indicated their readiness through their more focused discussion on the baby and becoming a mother. Comments included, “But now, it's becoming more about the baby and it's becoming more tangible and it's becoming less about the pregnancy and more about—you know, names” and “You know, the more I can't wait to meet the baby. I don't really care about the labor—you know, yeah, we have labor. Well, labor is labor. You know. But it's the baby, you know” (P #1). Others acknowledged the major change that was about to occur in their lives: “…and the fact that I have to be a mom. That kind of weirds me out more than anything else, that I'm going to be somebody's mom” (P #5) or “…there's no way you can anticipate what it's going to be like. It's sort of like any huge life change” (P #2).

DISCUSSION

Overall, the participants' narratives support a relationship between childbirth education and readiness for the childbirth experience. Previously researched concepts—for example, control and decreased anxiety—emerged as important, but not one of them alone was consistently significant as an outcome associated with participation in education classes. Theoretically, it seems reasonable that these concepts were actually process indicators of the overall outcome of readiness. Other than methodological issues (e.g., small sample size, lack of control of instructor qualifications, class content, etc.), this could possibly explain the inconsistencies of many of the previous findings.

The childbearing experience has consistently been described in the literature as a significant event in a woman's life and as a developmental stage (Bergum, 1989; Lederman, 1996; Malnory, 1996; Nichols, 1996; Rubin, 1984). Rubin's (1984) discussion of maternal tasks suggested that pregnancy and birth involved negotiating a journey: “From onset to destination, childbearing requires an exchange of a known self in a known world for an unknown self in an unknown world” (p. 52). Furthermore, Rubin stated, “…a woman perseveres pragmatically in the here and now, one step at a time, doing what has to be done in the situational context, recruiting resources within herself, her family, and her social systems” (p. 52). Thus, childbirth education can be viewed as one of the steps toward the goal of becoming a mother. Likewise, Lederman (1996) and Mercer (1995, 2004) suggested that successfully completing the tasks of pregnancy assists the woman in this paradigm shift (to motherhood).

Meleis, Sawyer, Eun-Ok, Messias, and Schumacher's (2000) middle-range theory of Experiencing Transitions provided additional insight and support for development of the emergent theory of Negotiating the Journey to motherhood. Meleis et al. included pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting as developmental and lifespan transitions. The Experiencing Transitions model, although complex and multidimensional, includes five essential, interrelated properties: (a) awareness, (b) engagement, (c) change and difference, (d) time span, and (e) critical points and events. Findings in the current study revealed properties similar to the Experiencing Transitions model. The women were aware of the major change that was about to occur in their lives and that they were in need of real knowledge. Thus, they engaged in focused knowledge-gathering by attending childbirth education classes. As a result, the women expressed a change and difference in their knowledge, anxiety, confidence, and feelings of control. These changes occurred over the time span of the classes. Subsequently, when the women reached a critical point, they voiced their readiness for birth.

Implications for Practice

As expected and demonstrated by the stories of these nine women, the women did not view a “drug-free” or “intervention-free” birth as the ultimate goal of the childbirth experience. This finding is not surprising, because these women had grown up within the medical model of birth that is highly prevalent in our culture. Rather, the nine women highly valued the classes as a way to define and clarify the birthing process and to help them prepare for becoming a mother. They found that, through the classes, they not only gained the knowledge they had desired but also gained other benefits. Consistent with Stamler's (1998) findings, the women described how the classes had strengthened their relationships with their husbands, increased their confidence in themselves, and empowered them to have some control over a situation that was often out of their control.

Women in the study highly valued childbirth education classes as a way to define and clarify the birthing process and to help them prepare for becoming a mother.

Thus, the Negotiating the Journey model has the potential for use as a framework for designing and implementing classes. The findings suggest that viewing childbirth education as an integral part of a larger scheme, or what is often referred to as “the big picture,” can help the educator to understand what is important to women. The comments from these women indicate that, although the labor process is an extraordinary event, its magnitude diminishes next to the task of becoming a mother. However, that does not minimize the value of educating on the birth process, because it was through these classes that the women gained confidence in their abilities.

The women came to class with a host of information from various sources, searching to make sense of what they had heard, read, and seen. They wanted someone to sort and organize the information into an uncluttered reality of childbirth. The women made it clear that knowledge of the options available to them was a highly valued asset that helped them to feel in control. However, control may be more related to those options not involving medical intervention. In support of this conclusion, Green and Baston's (2003) study found three types of control that contributed to positive psychological outcomes: control of what health-care staff does to the woman, control of the woman's own behavior, and control during contractions.

Finally, the women's discussions of the classes also demonstrated the importance of partner participation. The women valued the increased bonding that occurred through class participation, even to the extent of stating that this was the most important outcome of the classes. Therefore, the role of the partner also needs to be further emphasized and facilitated.

Limitations of the Study

Given the inevitable restraints of limited resources and time, the present study was limited by its inability to include all possible data that would be helpful in shedding light on women's perceptions of childbirth education. In this study, the sample consisted of a group of homogenous participants. There were no women of non-Caucasian origin or from a low socioeconomic status. Such women were not purposely excluded. It is well known that women in this country who attend classes are predominantly Caucasian, middle to upper-middle class, and educated first-time mothers. That does not mean that no other women attend classes. A few do, but those women did not happen to volunteer for participation in this study. It is highly likely that a more heterogeneous sample of women would lead to further development of the categories that contribute to the grounded theory. However, every attempt was made to reach saturation.

In addition, no attempt was made to control for the specific content of classes or the qualifications of the instructors. All agencies do not require the same standardized classroom content; thus, that type of control would have been exceedingly difficult to accomplish. However, because the purpose of the study was to understand process, standardization of classes was less relevant to the outcome.

Recommendations for Future Research

The findings of the present study provide a guide for childbirth education evaluation research. Although much work remains to be done before it is practically useful for evaluation studies, the current grounded theory is a beginning. As readiness emerged as an important outcome in this study, a review of the literature for an appropriate instrument demonstrated only one. Fleury (1994) developed the Index of Readiness to measure individual appraisal of readiness to initiate health-behavior change. The inductively generated dimensions of this instrument (image of self, re-evaluation of lifestyle, identification of barriers, goal strategies, commitment, and control) appear to be conceptually related to categories and properties identified in the present study. Although Fleury's instrument is not specific to readiness for childbirth, it may serve as a resource for the development of an appropriate readiness instrument.

Furthermore, a need exists for methodologically sound studies that examine the childbirth experiences of women who do not participate in childbirth education (Nichols & Gennaro, 2000). This topic suggests several questions for research: Do women who do not go to childbirth education classes achieve the same level of readiness for childbirth as the women in the present study? If so, how is this accomplished? Would they describe readiness in the same terms? If they do not express readiness, what educational interventions are appropriate? What are the best strategies for providing that education?

CONCLUSIONS

Negotiating the Journey provides a theoretical framework specifically focused on contemporary women's perceptions of childbirth education. The generation of this model contributes to the body of scientific knowledge regarding childbirth education and provides a beginning framework to guide further development of childbirth education.

Overall, this study highlighted the strengths and challenges of childbirth education. The strengths were apparent as the researcher heard and observed the women's expressions of readiness for birth. The challenge is how to promote and enhance the indicators of readiness not only to the women who choose to attend classes but also to the many women who do not participate or have the opportunity to participate in formal classes. It is hoped that the generation and presentation of this theory on how women perceive childbirth education will sensitize childbirth educators and other health-care professionals to listen to childbearing women and respond to their needs.

Footnotes

This is our first baby, and so there is a lot of new things we're going to encounter and I think it's just helpful to know some tips and different things that can help the process go a little smoother. (P #7).

This is our first baby, and so there is a lot of new things we're going to encounter and I think it's just helpful to know some tips and different things that can help the process go a little smoother. (P #7).

REFERENCES

- Beger D, Beaman M. Childbirth education curriculum: An analysis of parent and educator choices. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1996;5(4):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bergum V. 1989. Woman to mother: A transformation. Granby, MA: Bergin & Garvey. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R. A. 1965. Husband-coached childbirth. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Dick-Read G. 1944. Childbirth without fear: The principles and practice of natural childbirth. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Enkin M, Keirse M, Renfrew M, Neilson J. 1999. A guide to effective care in pregnancy & childbirth (2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury J. D. The index of readiness: Development and psychometric analysis. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1994;2:143–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A. J. 2004. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth/parenthood. In The Cochrane Library (Vol. Issue 4. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. 1978. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. 1992. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G, Strauss A. L. 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Green J. M, Baston H. A. Feeling in control during labor: Concepts, correlates, and consequences. Birth. 2003;30:235–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren A, Kihlgren M, Norberg A, Forslin L. Women's perceptions of childbirth and childbirth education before and after education and birth. Midwifery. 1995;11:130–137. doi: 10.1016/0266-6138(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humenick S. S. 2000. Program evaluation. In F. H. Nichols & S. S. Humenick (Eds.), Childbirth education: Practice, research, & theory (2nd ed., pp. 593–608. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. C. 1983. A meta-analytic study of the effects of childbirth education research from 1960 to 1981. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn M. L. Effectiveness of prepared childbirth and childbirth satisfaction. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1992;1(2):35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn M. L. Childbirth education outcomes: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Perinatal Education. 2002;11(3):10–19. doi: 10.1624/105812402X88795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaze F. 1970. Painless childbirth: Psychoprophylactic method (L. R. Celestin, Trans. Chicago: Henry Regnery. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman R. P. 1996. Psychosocial adaptation in pregnancy: Assessment of seven dimensions of maternal development (2nd ed. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S, Guba E. G. Establishing trustworthiness. 1985. In Naturalistic inquiry (pp. 289–331). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Malnory M. E. Developmental care of the pregnant couple. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25:525–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell L. K. From innovation to common practice: Perinatal nursing pre-1970 to 2005. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2006;20:8–16. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis A. L, Sawyer L. M, Eun-Ok I, Messias D. K. H, Schumacher K. Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. Advances in Nursing Science. 2000;23:12–28. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer R. T. 1995. Becoming a mother. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer R. T. Becoming a mother versus maternal role attainment. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols F. H. The meaning of the childbirth experience: A review of the literature. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1996;5(4):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols F. H, Gennaro S. 2000. The childbirth experience. In F. H. Nichols & S. S. Humenick (Eds.), Childbirth education: Practice, research, and theory (2nd ed., pp. 66–83. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan M. Antenatal education—Where next? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25:1198–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan M. Antenatal education: Past and future agendas. The Practising Midwife. 1999;2(3):24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty. Ltd. QSR NUD*IST (Version 4. 1997. Thousand Oaks, CA: Scolari.

- Rubin R. 1984. Maternal identity and the maternal experience. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Jones N, Graham S, Crowe K, Nigro S, McLean B. Prenatal class evaluation. International Journal of Childbirth Education. 1998;13(3):28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Slaninka S. C, Galbraith A. M, Strzelecki S, Cockroft M. Collaborative research project. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1996;5(3):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Spiby H, Slade P, Escott D, Henderson B, Fraser R. B. Selected coping strategies in labor: An investigation of women's experiences. Birth. 2003;30:189–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler L. L. The participants' views of childbirth education: Is there congruency with an enablement framework for education? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;28:939–947. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. Felt learning needs of pregnant women. The Canadian Nurse. 1993;89(1):42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2000. Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health (2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved November 14, 2007, from http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/tableofcontents.htm#under. [Google Scholar]