SYNOPSIS

Historically, local public health in Massachusetts has been largely decentralized, with each town responsible for providing local public health services. After 9/11, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) began to plan for bioterrorism and other possible public health emergencies and found that having 351 separate departments made emergency planning difficult and dispersing of funds a challenge. To facilitate this process, MDPH created seven emergency preparedness regions and asked local public health departments to engage in joint planning. This article describes the formation of Region 4b and how the region came together to work on emergency preparedness issues. It also examines the organizational, financial, and planning challenges associated with organizing these towns as a unified entity.

The events of 9/11 and the use of anthrax as a bioterrorist weapon drove home the message that threats to the public health can occur at any time, and forced us to relearn the forgotten lesson that these emergencies do not respect political boundaries. In Massachusetts, it became clear that public health lacked the infrastructure to meet these evolving threats. With county governments largely dismantled, the state was dependent upon a decentralized, local public health system that was inadequately funded and unevenly staffed.

BACKGROUND/REGIONAL CONTEXT

Massachusetts has a 300-year history of strong home rule. Since 1799, when Paul Revere established the nation's first public health board in Boston, each city and town has taken responsibility for the provision of public health services. This has resulted in a mosaic of 351 local health entities statewide, each responsible for the same set of state-prescribed services, whether it be for Boston, with a population of 600,000, or for Monroe, a town with approximately 100 residents in western Massachusetts. While larger municipalities—those with populations >45,000—are able to meet most, if not all of their responsibilities, smaller and mid-sized communities must perform public health triage, providing only those services deemed most essential to their citizens' well-being. Clearly, this structure dilutes the effectiveness of much of the state's public health efforts.

It is helpful to compare the Massachusetts experience with that of the rest of the country. Nationally, regional public health departments (generally county-based) provide services to an average of 90,000 individuals and are responsible for an area of approximately 1,260 square miles. By contrast, a local public health department in Massachusetts provides services to an average of 18,000 people and is responsible for an area with a mean of 31 square miles. (Unpublished data, Cohen A. Local public health infrastructure in central Massachusetts: a case for consolidation; 2000.) As local public health departments added emergency preparedness to their responsibilities, it became clear that “business as usual” needed to be rethought, and that support for interdepartment, cross-boundary cooperation was necessary.

THE EVOLUTION OF A MASSACHUSETTS EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS REGION 4B

With its strong tradition of local autonomy, Massachusetts has typically not been receptive to public health collaboration across community boundaries. In 2000, however, when West Nile virus (WNV)-positive mosquitoes and birds first began to appear in eastern Massachusetts, local health directors from Boston, Newton, Brookline, and Cambridge met to coordinate strategies for response and protection in their communities. These four communities formed the nucleus for the coalition of cities and towns that would eventually form Region 4b.

As WNV spread to neighboring communities, the conversations expanded to include local public health agencies (LPHAs) in these cities and towns. When a series of suspected anthrax incidents made the news in the area, these agencies again worked together to coordinate their response and develop consistent public information messaging. This series of collaborations eventually led to the creation of Clean Air Works, a 19-community regional effort to support enactment of local tobacco-free workplace ordinances.

The collaborative work that had begun with WNV evolved in response to the changing public health climate, especially as money began to flow into bioterrorism and emergency preparedness. It was clear that an act of terrorism could produce mass casualties, disrupt services that affect public health and safety in multiple communities at once, and quickly overwhelm local resources. Although LPHAs had long responded to public health emergencies such as infectious disease outbreaks, or natural disasters such as blizzards, hurricanes, and floods, they had little experience with bioterrorism or weapons of mass destruction.

In 2002, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) began the process of identifying seven public health emergency preparedness regions statewide. The effort was initiated largely in response to bioterrorism funding received through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cooperative Agreement on Public Health Preparedness and Response for Bioterrorism (Cooperative Agreement). To get funding into local departments, these funds had to be distributed either directly to 351 cities and towns, or through a regional structure that didn't exist. Public health emergency preparedness regions were proposed as an efficient conduit for distributing local preparedness funding. Additionally, the regions would encourage cooperation across community boundaries and promote regional planning.

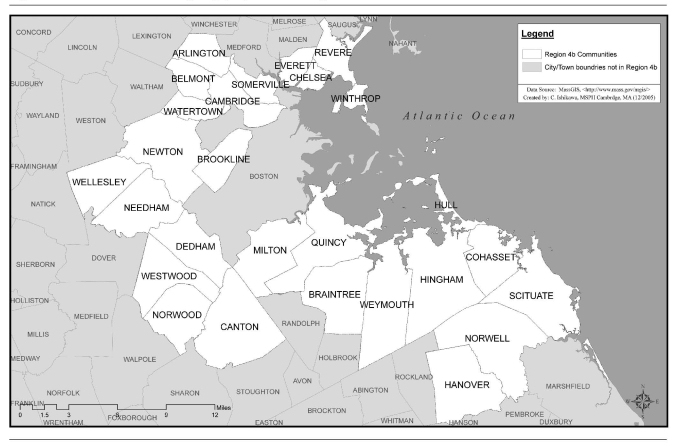

In fall 2002, building on their history of cooperation, local health authorities for 25 communities in Region 4b (the cities of Chelsea and Everett subsequently joined Region 4b) signed a letter of intent to work collaboratively as a region to meet the goals associated with MDPH emergency preparedness initiatives. In 2003, Region 4b was authorized to hire its own coordinator (MDPH provides coordinators for all other regions except for the city of Boston), and the Cambridge Public Health Department (CPHD) agreed to serve as the region's host agency. Region 4b began meeting regularly and hired its regional coordinator in September 2003 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Communities in emergency preparedness Region 4b

By the end of 2003, all seven emergency preparedness regions were in place: Region 1, western Massachusetts; Region 2, central Massachusetts; Region 3, northeastern Massachusetts; Region 4a, metro-west; Region 4b, metro-Boston; Region 4c, Boston; and Region 5, southeastern Massachusetts. Each region identified a host agency, and five of the seven regions worked with coordinators hired by MDPH. Initial bioterrorism funding was distributed by MDPH according to a population-based formula in February 2004 (Figure 1).

Both the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) and MDPH have played and continue to play an important supportive role. During both the WNV and anthrax emergencies, BPHC worked collaboratively with neighboring communities and provided technical support. This collaboration has continued since the establishment of Regions 4b and 4c. Boston's regional coordinator participates in the Region 4b monthly meetings, and both regions have jointly participated in exercises and response to real events. BPHC is a signatory to the Region 4b public health mutual aid agreement.

In addition to its role as a funding agency for Region 4b, MDPH also provides educational and training opportunities for the region. The Region 4b health educator, an MDPH employee, regularly attends regional meetings and meets with the regional coordinator. Additionally, senior MDPH staffers have routinely attended Region 4b's monthly meetings, using them as opportunities to brief local directors on issues such as infectious disease, WNV and Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) testing, flu vaccine availability, and other public health policy issues. This level of participation and support has been and will continue to be crucial to the region.

MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE OF 4B

Management

Region 4b was initially staffed by a single full-time regional emergency preparedness coordinator, who was hired by CPHD with funding from MDPH. The regional coordinator is an employee of the CPHD and maintains a working relationship with the MDPH. In 2005, the region approved hiring of an assistant regional coordinator, who is also an employee at CPHD.

In 2004, CPHD secured funding through the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) to establish an Advanced Practice Center for Emergency Preparedness (APC). The APC, one of only eight nationwide, focuses on development of regional models for collaboration and partnership building, preparedness planning, and disease detection and response. Cambridge APC work has included development of the regional mutual aid agreement; sponsorship of multidisciplinary, multi-community exercises; implementation of a local emergency notification system (LENS) for after-hours emergencies; and work on an index of readiness to measure progress in local health preparedness. The APC funding supports additional staff members at CPHD who augment the work of the coordinator and assistant coordinator, and enable the region to undertake emergency preparedness initiatives that would otherwise be beyond its reach.

Governance

Coordinating the needs and expectations of 27 towns is a challenge under the best circumstances. Given the urgency of emergency preparedness, it is essential that the participating communities come to consensus regarding the region's management. In January 2004, the region adopted Principles of Operation to govern the region's work.1 These Principles establish clear rules for decision-making and responsibilities. They also include protections to ensure that the region's smaller communities have a voice equal to that of their larger partners. These Principles form the foundation for regional collaboration and support, and are an essential underpinning to the region's ability to work together in response to an emergency situation.

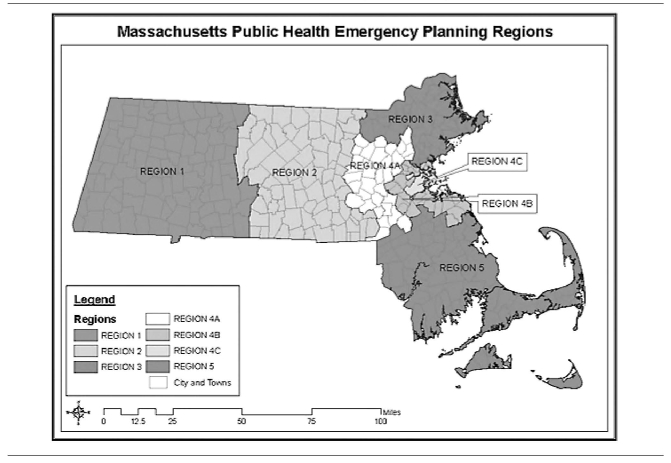

Under the Principles, a five-member executive committee is responsible for overall administration and management of Region 4b activities. To ensure equitable representation, the region has identified four groups of communities, stratified by population (Figure 2). The executive committee is chaired by a representative of CPHD, and each January, the group designates an executive committee member.

Figure 2.

Diagram of Massachusetts public health emergency preparedness planning regions

Executive committee members delegate responsibility for day-to-day operations to the regional coordinator and assistant coordinator. Decisions of the executive committee are subject to review by the full region, which meets monthly.

Planning subregions

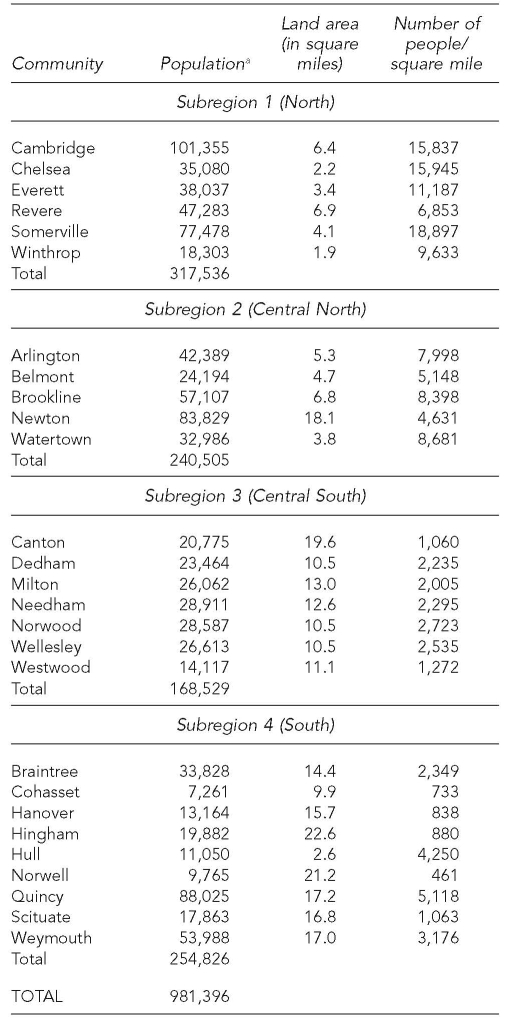

Although the region operates as a single coalition, communities are assigned to four geographically determined subregions to facilitate planning and exercise activities. Table 1 provides information by subregion. Establishment of the subregions has resulted in manageable planning entities that contain populations closer to the figure identified as optimal for regional services.

Table 1.

Population density by Region 4b community

aU.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2002.

COORDINATING A REGIONAL RESPONSE TO A PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY

Following the recent establishment of emergency preparedness regions, public health partners are still working to define local, regional, and state responsibilities. The Region 4b Emergency Operations Plan (REOP) recently submitted to NACCHO as part of the region's Public Health Ready application outlines the current understanding of these relationships and roles. As identified in the REOP, LPHAs are responsible for:

Developing and exercising local public health all-hazards response plans consistent with their community's Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan;

Informing community residents regarding prevention and control measures and local effects of disease;

Maintaining ongoing disease surveillance and investigation activities as required by state law and state and local regulations;

Identifying and maintaining essential public health functions during periods of emergency and high absenteeism; and

Dispensing vaccine and other emergency treatment through emergency dispensing sites established and operated with MDPH guidance.

A Region 4b community or other signatory to the mutual aid agreement can request technical assistance, support, and coordination of resources from the region or MDPH. The region will first identify and mobilize resources available in the region, and will also serve as a liaison between LPHAs and the state for the purpose of mobilizing resources. In situations where local and regional capacity is exceeded, the local health department and its emergency management director will contact the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency to mobilize additional resources following procedures in the local Community Environmental Monitoring Program.

The region is responsible for:

Maintaining region-wide emergency notification and alerting lists to facilitate mobilization of resources in a disaster or special event;

Identifying existing resources (personnel, supplies) available in the region that can be used to supplement local resources;

Mobilizing existing resources as required in a public health event or emergency affecting one or more communities in Region 4b;

Implementing mutual aid agreements, memoranda of understanding, or other arrangements to secure supplemental personnel, supplies, or access to facilities to support regional emergency response;

Prioritizing use of regional emergency preparedness funding to support regional needs;

Supporting LPHAs with emergency operations plan development and revision;

Conducting REOP exercises on a regular basis;

Conducting training on the REOP for communities in the region and other partners; and

Updating and revising the regional emergency operations plan annually or more frequently as necessary.

When the state's Emergency Operations Center is activated, MDPH is the lead state agency for coordinating public health, mental health, and medical resources as requested by local authorities in areas affected by a disaster or special event. MDPH is responsible for:

Assessing health and medical needs;

Coordinating emergency medical services;

Providing technical assistance in environmental and communicable disease control/epidemiology;

Testing biological and toxicological samples through the state laboratory;

Providing medical equipment and supplies for hospitals;

Conducting credentialing of health-care providers through the Massachusetts System for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals;

Developing patient identification and tracking systems;

Coordinating hospital care;

Supporting mass immunization and emergency dispensing activities, as well as managing the Strategic National Stockpile;

Ensuring food and drug safety;

Assisting in addressing radiological, chemical, and biological hazards;

Coordinating mental-health and crisis counseling; and

Issuing public health information.

A table describing the region's plan-activation typology can be found at http://www.cambridgepublichealth.org/publications.php.

FUNDING ISSUES

Region 4b and the other emergency preparedness regions are funded by MDPH pursuant to the CDC Cooperative Agreement. Within guidelines established by MDPH, each region determines its own spending priorities and procedures. In its initial funding year, Region 4b received and disbursed approximately $600,000 in base funding, plus an additional $54,000 to support computer purchases for each community. These preparedness funds were used to strengthen infrastructure and increase capacity to respond effectively to a range of public health emergencies. Approximately 43% of the initial funding was distributed directly to the participating communities, with the remainder used to support region-wide activities and cover host agency operating costs.

MDPH funding has declined in subsequent years as CDC funding to the state has declined. For year three, base funding for the region was approximately $508,000. Despite the reduction, the region maintained local allocations at the level established in year one. In year four, the region is expected to receive approximately $432,000, and has voted to adjust local allocations in light of the reduction. The region will receive additional dollars through the supplemental pandemic flu funding distributed to the state.

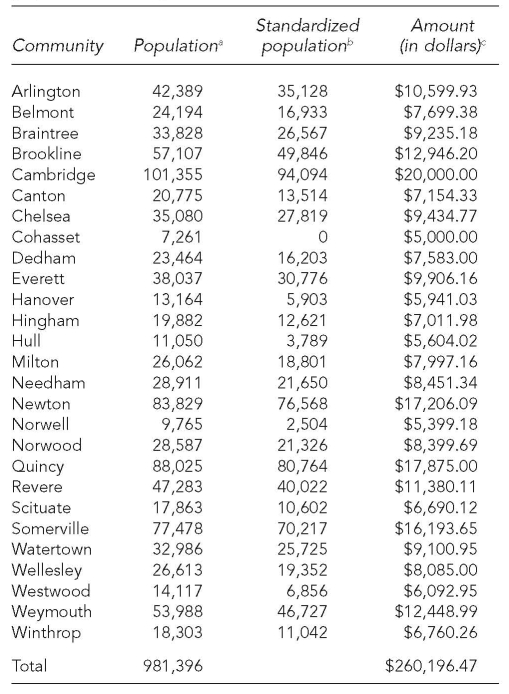

Funding for local departments

Each year, the region has allocated approximately $260,000 to local health departments to build and support infrastructure. Local allocations are calculated according to a sliding-scale formula based on population figures as reported in the 2000 Census.2 The smallest community, Cohasset, received $5,000, and the largest community, Cambridge, received $20,000. Table 2 shows the funding breakdown for the first year.

Table 2.

Funding distribution by population in Region 4b

aPopulation figures taken from the 2000 U.S. Census. U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2002.

bStandardized population is population minus 7,261 (using the population of Cohasset to set everyone on a scale).

cThe formula for amounts = (Standardized Population 3 0.159415053) + $5,000.

Determined by taking the difference between the largest and smallest populations (101,355 − 7,261 = 94,094), and the difference in amount being allocated ($20,000 − $5,000 = $15,000). Dividing the difference in funds by the difference in population ($15,000/94,094 = 0.159415053) gives you the amount of money per resident in the community. Then, $5,000 is added to each amount to establish a scale so that the smallest community receives $5,000 and the largest $20,000.

Local allocations have been used by the LPHAs on a discretionary basis for local emergency preparedness activities that enhance the region's ability to respond to public health emergencies. To ensure regional oversight of expenditures, satisfy MDPH funding deliverables, and promote regional consistency in activities funded with local allocations, each member LPHA has been required to submit an annual plan to the regional coordinator. The plan describes the LPHA's intended use of its local allocation and includes a timeline for project completion. All plans are reviewed and approved by the executive committee. Plans may be amended with approval of the executive committee and the regional coordinator, and in accordance with MDPH guidelines.

Local allocations have been used to:

Hire backup support consultants or independent contractors to assist with local public health duties (e.g., food inspections, public health nursing, tobacco compliance inspections) so that LPHA staff can participate in local and regional public health emergency preparedness planning and related activities;

Support collaboration with other emergency preparedness partners in the community, such as hospitals, community health centers, public safety agencies, and town officials; and

-

Hire an emergency preparedness consultant to coordinate local preparedness activities related to:

—Developing local emergency response, risk communication, medical reserve corps, and other emergency response plans or plan components in collaboration with the regional liaison;

—Working with the regional consultant to develop plans for local and regional mass vaccination and dispensing sites; and

—Other local emergency preparedness needs as approved in advance by the executive committee in accordance with MDPH guidelines.

Funding for regional needs

Funds remaining after the distribution of local allocations support regional projects and administrative overhead (15% of the regional award is allotted to the fiscal agent). The region has identified the following as appropriate regional goals:

Work on developing a regional system to provide public health inspections, surveillance activities, and public health nursing services to some or all of the communities in Region 4b;

Hire regional liaisons to work with the regional coordinator and local communities to develop local and regional plans;

Provide support and coordination of local and regional development of plans for mass vaccination and dispensing clinics;

Conduct regional and subregional drills;

Provide funding to help cover the costs of appropriate staff training, including exercises and drills, related to bioterrorism and other public health emergencies; and

Other regional emergency preparedness projects and expenditures as authorized by the governing body of Region 4b in accordance with MDPH guidelines.

REGIONAL ACTIVITIES AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS

The region's two major goals have been to (1) strengthen individual communities' capacity to respond and (2) to develop a centralized regional support structure that enhances the capabilities of each community to respond to a public health emergency. An additional goal has been for the communities to create structures that support cross-boundary sharing of resources in case an emergency overwhelms a community's ability to respond. It is anticipated that the remaining communities will complete the execution process by 2008.

Planning and development initiatives

Prior to the region's establishment, municipalities had achieved varying levels of emergency preparedness. To coordinate and begin to standardize these capabilities, the region undertook the following initiatives.

Completion of local all-hazards plan for each jurisdiction.

Each local health department in Region 4b has developed an all-hazards response plan, with most communities using a template adapted from work developed by the Massachusetts Health Officers Association with MDPH funding. The process of working through the template has helped communities develop thoughtful strategies around the deployment of personnel and the use of resources, and formalize their relationships with other community emergency responders. There are basic expectations for each health department's all-hazards plan, including development of an incident command structure, emergency dispensing site (EDS) operations procedures, risk communications protocols, pandemic influenza preparedness, and continuity of operations planning. To support the local departments, the region hired a consultant who worked with each of the communities to ensure that plans met standards established by MDPH, and were comprehensive, clear, and consistent. The consultant was supported by four regional liaisons, who were public health graduate students from the Boston University School of Public Health (BU SPH).

Completion of REOP.

In September 2006, the communities in Region 4b adopted an REOP. The regional all-hazards plan was designed to supplement the local plans and establish policies and procedures for centralized coordination of resources and support. The REOP may be activated in the event of a local emergency that exceeds an individual community's capacity to respond, or in a multi-community emergency requiring cross-boundary response. The REOP and its workforce training and exercise components were the basis for the region's recognition by NACCHO as Public Health Ready in February 2007.

Mutual aid.

A major public health threat—such as a chemical spill or disease outbreak—could rapidly overwhelm the resources of a single community. A public health mutual aid agreement is a legal document that addresses issues of liability, authority, and finances that often arise when one community's public health department requests help from another. The Cambridge APC worked with MDPH, representatives of town governments and city solicitors, and the Massachusetts Association of Health Boards to draft a model mutual aid agreement. The model was released to the MDPH regional coordinators in December 2005 for distribution across the state. In late 2005, the 27 Region 4b communities began the local process for approval. As of May 31, 2007, 24 communities have approved the agreement. Twenty-one of these communities and the city of Boston have now formally executed the agreement.3

Regional resources database.

A companion piece to the mutual aid process has been the development of a regional database. This database will identify, by municipality, resources that could be made available in the event of a region-wide emergency. The database will list public health staff in the region, along with licensure and skill set information, and provide an inventory of materials, supplies, and equipment that can be deployed in response to a request for mutual aid by a participating community.

EDS action plan.

During a major public health emergency, it is essential that people who are at risk for illness have access to life-saving medicines and vaccines. EDSs are temporary clinics set up in schools, churches, and other community locations to provide medication and vaccines to a large number of people in a short amount of time. In 2005, the APC produced an EDS action plan for use by municipal health officials and other public health workers in the 27 Massachusetts communities in Region 4b. This action plan serves as the regional standard for opening, operating, and closing EDSs. The emergency dispensing plan has been incorporated into the public health all-hazards plans for Region 4b communities. The APC has developed and conducts ongoing regional trainings on the plan and facilitates exercises for public health staff on implementing the plan.

LENS.

In summer 2005, regional staff and the APC worked with MDPH to develop a system to notify and support LPHAs in the event of a public health emergency occurring outside of regular business hours. This plan was approved by the region and the MDPH Bureau of Communicable Disease Control (BCDC). The system works with the state's Health and Homeland Alert Network, and is staffed on a rotating basis by the regional coordinators and APC staff. LENS went live in September 2005. Since then, the region has organized a series of off-hours drills for communities in Region 4b, regional on-call staff, and BCDC staff. These drills have been useful in identifying areas of improvement, which have been used to refine this system. In 2006, this system was used for actual events, such as a measles outbreak that affected the city of Boston and communities in the region; a case of bacterial meningitis; reports of suspicious powders; and suspected and confirmed cases of WNV and EEE.

Pandemic flu tabletop exercise.

In May 2005, the APC organized a conference on the essential role of public health in local emergency preparedness, which featured a pandemic flu tabletop exercise. In the fictional scenario, developed with the Harvard Center for Public Health Preparedness, a man arrived at a Boston-area hospital with flulike symptoms. The man had recently returned from a business trip to Asia, and had potentially infected several hundred passengers on his flight home. He had also attended a large awards dinner in Cambridge directly following his trip. Over the next 11 days, hospitals were flooded with patients, including their own medical staff.

The exercise brought together public health officials, town administrators, firefighters, police, emergency medical staff, hospital staff, and public works staff from 13 communities in Region 4b. The representatives from each community developed a response for their municipality, identifying, in the process, strengths and potential gaps in their preparedness planning. For some communities, it was the first opportunity for their emergency preparedness first responders to work together on a response scenario.

Due to the success of this exercise, a second pandemic flu exercise was organized in September 2005. More than 200 people from Cambridge, Boston, Somerville, Everett, Chelsea, Revere, Winthrop, Brookline, Quincy, and MDPH participated. In addition to intracommunity response, this exercise sought to test collaboration and information sharing across community boundaries, and among state and local health officials. Since that time, the APC has conducted single community trainings in three Region 4b communities. These trainings are tailored to reflect the special issues associated with each community.

Regional liaisons.

In an effort to provide additional support to the communities of Region 4b, the region allocated funding for four part-time regional liaison positions. Working in collaboration with the BU SPH, the region has recruited graduate public health students who work with individual health departments and the regional coordinators to focus on completion of local and regional emergency response plans, and to support activities that enhance the region's capacity to respond to public health emergencies such as an influenza pandemic, bioterrorist act, or natural disaster.

Development of regional Medical Reserve Corps.

Disasters such as Hurricane Katrina and the Southeast Asia tsunami have demonstrated the need for an organized group of qualified volunteers who are prepared to help, and who can be mobilized quickly. With this in mind, the assistant coordinator and the regional liaisons have worked with health directors in Region 4b to recruit and train volunteers for a Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) that would serve the region. In a disaster situation, these volunteers could be called upon to deliver medical care, interpret for individuals who do not speak English, or provide logistical or administrative support. Volunteers would also have the opportunity to assist local health departments in the region with routine activities, such as flu clinics and health screenings.

Brookline, Newton, Weymouth, Subregion 3 (a group of seven communities in Region 4b), and the region as a whole have established federally recognized MRCs:

The Region 4b MRC includes volunteers in all communities in the region, and oversees volunteer recruitment and mobilization for the federally recognized MRCs in Newton and Weymouth, as well as the communities of Arlington, Belmont, Braintree, Cambridge, Chelsea, Cohasset, Everett, Hanover, Hingham, Hull, Newton, Norwell, Quincy, Revere, Scituate, Somerville, Watertown, Weymouth, and Winthrop.

The Brookline MRC includes Brookline volunteers and coordinates activities with the Region 4b MRC.

The Subregion 4 MRC, recognized in December 2006, includes volunteers for Canton, Dedham, Milton, Needham, Norwood, Wellesley, and Westwood. Organized originally with Department of Homeland Security funding, this MRC shares volunteer information with the region and is expected to participate in the region-wide MRC database that is currently under development.

As of June 1, 2007, there were more than 2,000 combined medical and clerical volunteers in the combined MRCs.

Regional epidemiologic services pilot project.

Through the APC, the region has begun to assess the feasibility of providing centralized epidemiologic services within Region 4b to support public health emergency response, and to monitor, analyze, and report on regional health and disease status. According to the APC's 2005 and 2006 Capacity Assessment Surveys, only one community in the region has an epidemiologist on staff; 44% of the communities do not have staff trained to read and interpret statistical data; and 70% lack the capacity to perform statistical analyses on health data. In response to these findings, the APC has funded two regional epidemiologists to complete a demonstration project to pilot development of centralized epidemiology services to address these gaps.

Region 4b health directors have identified a need for assistance with analysis and reporting on the local and regional impact of existing health data sources, and with assistance in responding to communicable disease outbreaks. In 2006, the region partnered with BU SPH to establish a local practice/academic collaboration to support development of the data reports and centralized communicable disease protocols. Under the direction of the regional epidemiologist, BU SPH graduate epidemiology students have collected health data and compiled draft reports on health status indicators for local communities (if data are available), subregions, and the region as a whole. These data reports were to be distributed to the region in the late summer or early fall of 2008. The regional epidemiologists, working with BU SPH faculty and students, have collected information on communicable disease investigation needs through focus groups with public health nurses in the region. An online survey prioritizing needs was completed with the public health nurses in summer 2007, and policies and procedures for regional epidemiology support were completed in the fall of 2007.

Products include needs assessment tools, regional service policies and procedures, and tools to track provision of services and analyze service needs by community. As of May 2007, the APC epidemiologists had designed and developed a database to track and analyze data generated through LENS, supported the design and development of the MRC database, and were nearing completion of the Regional Resource Database.

The APC is working with MDPH-BCDC to coordinate proposed regional services with epidemiology services available through the state, and will continue to partner with MDPH to prioritize service needs and avoid duplication.

Completion of public health Continuity of Operations Plans.

A moderate-to-severe pandemic would place tremendous stress upon the medical infrastructure, as well as challenge public health departments' ability to provide essential services. With projected workforce absenteeism of 30% to 40% (e.g., employees out sick, staying home to care for sick family members, or staying out due to fear), it is presumed that all public health departments' ability to function would be significantly compromised.

Each of the local health departments in Region 4b has developed a Continuity of Operations Plan (CoOP) in anticipation of a possible pandemic or other emergency that would affect staff availability. In these plans, departments identify essential services and the personnel responsible for providing these services. Whenever possible, local departments have identified a backup staffing plan three-deep. In some instances, departments will need to draw personnel from other municipal departments, the region, or the MRC.

The REOP adopted by the region in 2006 also includes a CoOP to support necessary regional operations in the event of a pandemic or other emergency.

Operation of subregional flu clinics.

In late fall 2004, local and state health departments in the U.S. learned that there would be a severe and unanticipated shortage in the supply of vaccine due to poor production practices in one of the handful of laboratories that make influenza vaccine. This news prompted health departments to begin the difficult and controversial process of rationing the vaccine by risk of influenza morbidity and mortality. Despite the many challenges that the shortage presented, leaders within Region 4b were able to transform the crisis into an opportunity to further emergency preparedness planning.

With efforts already underway to develop plans for regionalizing public health services in the case of an emergency, the shortage of flu vaccine provided a real opportunity for health departments to grapple with the process of regionalization. Many of the communities within the region worked for the first time with subregional partners to plan and implement collaborative flu clinics. Subregional clinics were held from mid-December 2004 through January 2005.

During the 2005 and 2006 flu seasons, five communities organized subregional flu clinics that further tested elements of mutual aid, incident command, volunteer mobilization, and EDS operations under the EDS action plan. Exercise debriefs and after-action reports have identified strengths and opportunities for improvement of multi-community clinic operations, which were addressed in subregional flu clinics planned for the 2007–2008 flu season. To support these subregional efforts, the APC has developed materials to support low-cost operation and evaluation of flu clinic exercises.

The region has found subregional flu clinics to be an effective means of vaccinating the public. The experience was also invaluable in providing health officials with the experience of working collaboratively to accomplish a common goal. The ability to cultivate relationships, learn new techniques, and share resources was also seen as an important benefit. Health departments believe that the lessons learned from the subregional clinics are critical to successfully planning for emergencies. Despite initial concerns, the clinics provided a successful opportunity to work together and become familiar with one another before an emergency occurs.

CONCLUSION

It is difficult, if not impossible at this time, to parse how the elements of local and state responsibility and capacity for public health emergency response would play out in a large-scale emergency. Local public health retains primary responsibility for protecting local residents and managing public health response activities. Their resources are severely stretched, however, as they try to add emergency preparedness planning to an already long list of statutory and regulatory responsibilities. The influx of federal funding has not supported expanded or specialized local staffing—a large public health emergency would overwhelm the capacity of almost any LPHA in the Commonwealth.

However, the state's capacity to step in when a local department is overwhelmed has not been clearly defined. When the State Emergency Operations Center is activated, MDPH would assist local and regional entities in identifying and meeting the health, medical, and mental health needs of victims, emergency responders, and the public. In other situations, MDPH would likely support local response with laboratory services and specialized staff such as epidemiologists. MDPH's ability to provide staffing support or technical assistance will be limited, however, in emergencies that affect multiple communities simultaneously.

While work continues to define local and state roles, public health emergency preparedness Region 4b is bridging the gap between local and state response capacities. Despite initial skepticism, members of Region 4b are now strongly committed to cross-jurisdictional cooperation and centralization of emergency response services where possible. Since 2003, member communities have drafted National Incident Management System-compliant all-hazards response plans, upgraded emergency response equipment and supplies, strengthened relationships with other first responders, trained their workforces, participated in exercises and drills, and worked to build a functional, voluntary region. The region has funded a coordinator and assistant coordinator, approved a regional all-hazards response plan, developed 24/7/365 emergency notification capacity, advocated for implementation of a regional mutual aid agreement, adopted a standard EDS action plan, begun development of a regional epidemiologic services model, and developed and conducted exercises and drills to test local and regional capacity.

In 2008, the region will have its first opportunity to test its initial written REOP, which took effect on September 11, 2006. We anticipate that each exercise or real event will identify areas for improvement that will help to build an even stronger regional plan, and identify additional training needs to advance the skills of the region's workforce. And we fully expect that each event response, training, and exercise simulation will further strengthen the ongoing collaborations among the 27 communities of Region 4b that have chosen to work together to become better prepared to respond to their own or their partners' emergencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grieb J, Clark M. Principles of operation Massachusetts emergency preparedness region 4b. 2004. [cited 2008 Apr 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.cambridgepublichealth.org/services/emergency-preparedness/regional.php.

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cambridge Public Health Department. Mutual aid agreement among public health agencies in emergency preparedness region. [cited 2008 Apr 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.cambridgepublichealth.org/services/emergency-preparedness/regional.php.