SYNOPSIS

Objective.

Studies of stroke awareness suggest that knowledge of early warning signs of stroke is low in high-risk groups. However, little is known about stroke knowledge among individuals with a history of prior stroke who are at significant risk for recurrent stroke.

Methods.

Data from 2,970 adults with a history of prior stroke from the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System were examined. Recognition of the five warning signs of stroke and appropriate action to call 911 was compared across three racial/ethnic groups: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic/other. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to: (1) determine the association between race/ethnicity and recognition of multiple stroke signs and appropriate first action and (2) identify independent correlates of recognition of multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to seek treatment among individuals with prior stroke.

Results.

Recognition of all five signs of stroke and taking appropriate action to call 911 was lowest among the non-Hispanic black group (22.3%) and Hispanic/other group (16.7%). In multivariate models, Hispanic/other (odds ratio [OR] 0.42 [0.25, 0.71]), age 50–64 (OR 0.64 [0.43, 0.97]), age ≥65 (OR 0.36 [0.23, 0.55]), and >high school education (OR 1.79 [1.22, 2.63]) emerged as independent correlates of recognition of all five signs of stroke and first action to call 911.

Conclusions.

Less than 35% of people with prior stroke can distinguish the complex symptom profile of a stroke and take appropriate action to call 911. Targeted educational activities that are sensitive to differences in race/ethnicity, age, and education levels are needed for individuals with prior stroke.

Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the U.S., with estimated annual direct and indirect costs estimated at nearly $58 billion.1 A number of strategies are currently in place to reduce the incidence of stroke and the associated strain on financial and health-care resources. Presently, nationwide comprehensive campaigns are ongoing to increase public awareness of stroke, particularly early warning signs.2,3

Despite national efforts to improve stroke awareness, the public's knowledge of early warning signs of stroke remains low.4–9 Specific factors that contribute to poor stroke awareness remain unclear. For instance, although it is generally expected that individuals at greatest risk for stroke would exhibit greater stroke awareness, studies of at-risk individuals suggest otherwise. High-risk groups, racial/ethnic minorities,4,5,8,10,11 the elderly,4,5,8,10 and individuals with risk factors for stroke5,8,10 are least likely to recognize early warning signs of stroke and take appropriate action.

Individuals with prior stroke are one stroke risk factor group that has received minimal attention in the stroke awareness literature. Studies of stroke awareness among individuals with stroke risk factors traditionally emphasize hypertension,4,5,8,10 cardiovascular disease (CVD),4,5,8,12 diabetes,4,5,8,12 high cholesterol,4,8,12,13 smoking history,4,5,7,8,10,12 and other stroke risk factors. Fewer studies have considered individuals with prior history of stroke14,15 even though estimates suggest that within five years, 24% of women and 42% of men with history of prior stroke will have a second stroke.16 Further, individuals with history of prior stroke typically exhibit a number of associated factors (e.g., race/ethnicity, age, presence of other stroke risk factors) that increase their likelihood of a second stroke. Understanding stroke awareness in this high-risk group is critical to the development of appropriate educational strategies to reduce their likelihood of recurrent stroke. Furthermore, the study of this at-risk group would improve our understanding of independent correlates of stroke awareness and appropriate first action taken, thereby providing support to current efforts to decrease stroke incidence-associated burden.

The purpose of this study was to examine recognition of the five warning signs of stroke and appropriate action to call 911 in individuals with prior stroke. We chose to compare stroke awareness across racial/ethnic groups of individuals with prior stroke because racial/ethnic disparities exist in the recognition of early warning signs of stroke in the general population, even though racial/ethnic minorities are at significantly higher risk for stroke.1 We sought to examine the influence of race/ethnicity on stroke awareness in individuals with prior stroke and to identify independent correlates of recognition of early warning signs of stroke and appropriate action to call 911. Our research questions were as follows:

Are there racial/ethnic differences in recognition of multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to call 911 among individuals with prior stroke?

Are there racial/ethnic differences in odds of recognition of multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to call 911 after controlling for relevant covariates among individuals with prior stroke?

What are the independent correlates of recognition of multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to call 911 among individuals with prior stroke?

We hypothesized that: (1) individuals with prior stroke would differ in the recognition of multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to call 911 by race/ethnicity; (2) the odds of recognizing the multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to call 911 among individuals with prior stroke would differ by race/ethnicity after controlling for relevant covariates; and (3) independent correlates of recognition of multiple stroke signs and taking appropriate action to call 911 among individuals with prior stroke would emerge that differed by race/ethnicity.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study setting and sample

We analyzed data from the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. The BRFSS is a state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of the U.S. population ≥ 18 years of age sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.17 The BRFSS uses a complex sampling involving stratification, clustering, and multistage sampling to yield nationally representative estimates. Surveys include core questions asked of all participants in modules on specific public health topics of interest to state health programs. Our sample included only individuals that identified themselves as having had a stroke.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

We created three age categories: 18–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years. These age categories are used to detect gradients in stroke, which is known to increase with age. The age categories are defined by the BRFSS. We combined race and ethnicity to create three racial/ethnic groups: non-Hispanic whites (whites), non-Hispanic blacks (blacks), and Hispanic/other. Race/ethnicity is based on self-report using categories created by the BRFSS. Because the percentage of individuals who did not classify themselves as non-Hispanic whites (whites) or non-Hispanic blacks (blacks) was approximately 5% of the sample, a third category (Hispanic/other) was created by BRFSS to represent those who identified themselves as Hispanic, Asian, native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, and American Indian/Alaska Native.

Three levels of education—<high school graduate, high school graduate, and >high school graduate—were created; and four income categories—<$25,000, <$50,000, <$75,000, and >$75,000 were created. We defined marital status as married and not married; employment status as employed and unemployed; and insurance status as insured and uninsured. We defined perceived health status as excellent/very good/good vs. fair/poor and identified all individuals with a usual health-care provider. We identified presence of stroke comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and CVD.

Recognition of stroke warning signs and appropriate action to call 911

The recognition of early warning signs of stroke and action to initiate treatment was based on self-report. Responses were derived from the 2003 BRFSS Heart Attack and Stroke module. Respondents indicated whether any of the following warning signs were an indication of an imminent stroke: (1) sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding; (2) sudden numbness or weakness of the face, arm, or leg; (3) sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes; (4) sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination; and (5) sudden headache with no known cause. Respondents were also asked, “If you thought someone was having a stroke, what is the first thing you would do?” Respondents chose from a list of actions that included: (1) take the patient to the hospital, (2) tell them to call the doctor, (3) call 911, (4) call their spouse or family member, or (5) do something else.

Data analysis

STATA Version 8.018 was used for statistical analysis to control for the complex survey design of the 2003 BRFSS and provide estimates that generalize to the U.S. population. We performed four types of analyses. First, we compared demographic characteristics of participants by race/ethnicity. Second, we compared recognition of the five individual stroke signs and appropriate action to call 911 by racial/ethnic group.

Third, we ran multiple logistic regression models to examine the independent effects of race/ethnicity on recognition of each of the five individual stroke warning signs controlling for relevant covariates. Non-Hispanic white respondents served as the reference group in multivariate models. Covariates were selected based on clinical relevance and evidence of confounding effect on stroke recognition in prior studies. The covariates used in all multiple logistic regression models included age, sex, education, income, marital status, employment, insurance status, and comorbidity. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, and CVD.

Fourth, we ran multiple logistic regression models to identify independent correlates of: (1) recognition of all five warning signs collectively and (2) recognition of the five collective warning signs and appropriate action to call 911. In multivariate models, reference groups were: race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white); age (18–49); sex (men); education (<high school graduate); income (<$25,000); marital status (married); employment status (employed); insurance status (insured); diabetes (no); hypertension (no); CVD (no).

RESULTS

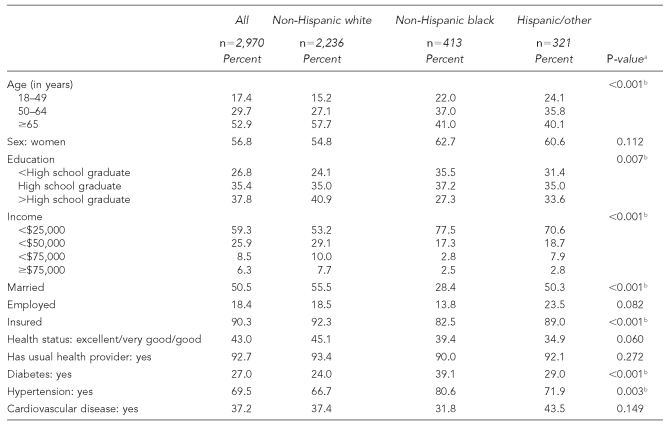

The 2003 BRFSS sample included 2,970 adults with prior stroke. Approximately 53% of the sample was ≥65 years old, 56.8% were women, 75.2% were white, 35.4% were high school graduates, 59.3% had incomes <$25,0000, 50.5% were married, and 18.4% were employed. About 90.0% had health insurance, 43.0% reported their health was excellent, very good, or good, and 92.7% had a usual care provider. Approximately 27.0% had diabetes, 69.5% had hypertension, and 37.2% had CVD. Table 1 compares the demographic characteristics of individuals with prior history of stroke by race/ethnicity. There were significant racial/ethnic differences by age, education, income, marital status, insurance status, and presence of diabetes and hypertension.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of individuals with prior stroke by race/ethnicity

P-value is for comparison across the three racial/ethnic groups.

Statistically significant at p<0.05

Recognition of signs of stroke and appropriate first action

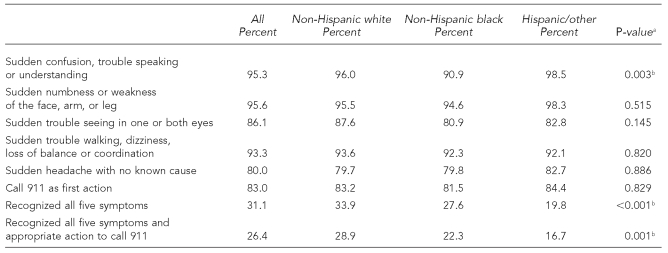

The majority of participants with prior stroke who participated in the 2003 BRFSS survey recognized individual warning signs of stroke. About 95% recognized sudden confusion, or trouble speaking or understanding; 96% recognized sudden facial weakness or numbness of the arm or leg; 86% recognized sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes; 93% recognized sudden trouble with walking, dizziness, or loss of balance or coordination; and 80% recognized sudden headache with no known cause as warning signs of stroke. Approximately 83% identified calling 911 as the appropriate action to take if someone was having a stroke. The recognition of the five warning signs of stroke and appropriate action to call 911 was low across the three groups. Overall, less than 32% of respondents recognized all five warning signs of stroke and only 26% recognized all five warning signs and would call 911 as an appropriate first action if someone was having a stroke (Table 2).

Table 2.

Recognition of signs of stroke and appropriate action by race/ethnicity in individuals with prior stroke

P-value is for comparison across the three racial/ethnic groups.

Statistically significant at p<0.05

Racial/ethnic differences in recognition of signs of stroke

Significant racial/ethnic differences were present in recognition of sudden confusion, or trouble speaking or understanding as a warning sign of stroke. Black people were least likely to recognize this symptom (90.9%) compared with white respondents (96.0%) and Hispanic/others (98.5%). Recognition of the remaining four individual warning signs of stroke was nonsignificant and relatively similar across groups. Significant racial/ethnic differences were present in recognizing all five stroke warning signs and appropriate action to call 911. Hispanics/others were least likely to recognize all five warning signs of stroke (19.8%) compared with white respondents (33.9%) and black respondents (27.6%). Hispanic/others (16.7%) were also least likely to recognize all five warning signs and would call 911 as the first action if someone was having a stroke compared with white (28.9%) and black (22.3%) respondents (Table 2).

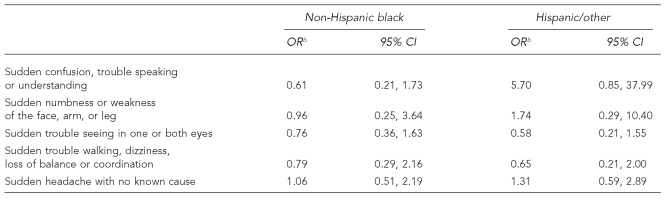

Odds of recognition of stroke signs by race/ethnicity

Table 3 shows the odds of recognizing the individual warning signs of stroke by race/ethnicity. With white respondents as the reference group and adjusting for relevant covariates, there were no significant racial/ethnic differences in recognizing any of the individual stroke warning signs.

Table 3.

Odds of recognition of signs of stroke by race/ethnicity in individuals with prior strokea

Non-Hispanic white is the reference group.

Odds ratio adjusted for age, sex, education, income, marital status, employment, insurance, and comorbidity. Comorbidity includes diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

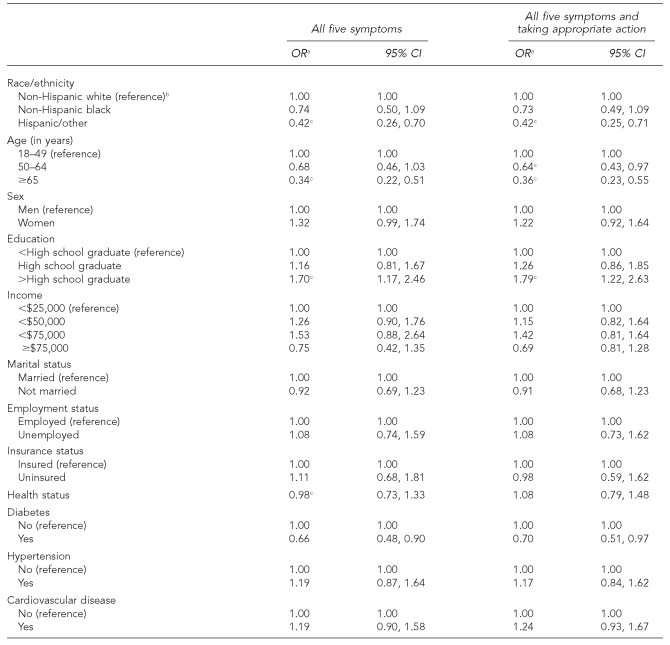

Independent correlates of stroke awareness and appropriate action

Table 4 shows the independent correlates of (1) recognition of the five collective signs of stroke and (2) the five collective signs of stroke and taking appropriate action to call 911. Race/ethnicity, age, and education emerged as factors that independently influence recognition of the five collective signs of stroke and taking appropriate action to call 911. With white respondents with prior stroke as the reference group, Hispanic/other (OR 0.42 [0.26, 0.70]) were less likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke. Hispanic/others were also less likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke and take appropriate action to call 911 (OR 0.42 [0.26, 0.70]). With individuals aged 18–49 as the reference group, respondents aged 50–64 (OR 0.64 [0.43, 0.97]) were less likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke and take appropriate action to call 911. Individuals aged ≥65 (OR 0.34 [0.22, 0.51]) were less likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke compared with the reference group (aged 18–49). Respondents aged ≥65 were also less likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke and take appropriate action to call 911 (OR 0.36 [0.23, 0.55]). Finally, with individuals having <high school education as the reference group, individuals with >high school education (OR 1.70 [1.17, 2.46]) were more likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke and also more likely to recognize the five collective signs of stroke and take appropriate action to call 911 (OR 1.79 [1.22, 2.63]).

Table 4.

Independent correlates of recognition of all five signs of stroke and taking appropriate action in individuals with prior stroke

Odds ratio adjusted for age, sex, education, income, marital status, employment, insurance, and comorbidity. Comorbidity includes diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Non-Hispanic white is the reference group.

Statistically significant

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrated that recognition of the individual warning signs of stroke is high among individuals with prior stroke. Similar levels of awareness exist across racial/ethnic groups of individuals with history of prior stroke, with the exception of sudden confusion, or trouble speaking or understanding, which was least likely recognized by black respondents. In contrast, few with a history of stroke recognize the five collective warning signs of stroke and would call 911 as a first action for treatment. Poor recognition of the multisymptom stroke profile (all five warning signs) and first action to seek treatment was low across all respondents, though significantly more prominent in black and Hispanic/other respondents.

In this study, we examined recognition of all five stroke signs collectively to provide a more accurate index of stroke awareness after stroke. Studies of stroke awareness typically assess recognition of individual warning signs/symptoms;4,5,7,8,10 however, measurement of individual warning signs of stroke does not provide an accurate index of awareness of the collective stroke signs that can occur. Many patients report significant difficulty in the identification of warning signs of stroke initially because stroke symptoms often vary in number and degree and can be hard to recognize.19

Our findings indicate stroke awareness is a multidimensional problem in those individuals at the highest risk for stroke (i.e., those with stroke risk factors such as history of prior stroke) for two reasons. First, the probability of stroke increases exponentially after the first occurrence of stroke. Second, this amplified stroke risk and greater need to understand warning signs of stroke is further complicated by factors related to race/ethnicity. Because race/ethnicity is believed to independently increase risk for stroke,4,5,8,10,11 improved stroke awareness is particularly critical for racial/ethnic minority populations with prior stroke.

Our previous investigations of stroke awareness suggest race/ethnicity may have a greater negative influence on stroke awareness than previously reported in the literature. We examined racial/ethnic differences in recognition of stroke warning signs and action to initiate treatment after stroke among 36,150 veterans in the 2003 BRFSS data.20 Recognition of the five individual warning signs of stroke was high among veterans; however, few recognized all five symptoms collectively or the multisymptom profile of stroke. Poor stroke awareness existed among veterans despite having equal access to primary and emergency care21 and more frequent and equal opportunity for stroke education. Given these disparities in stroke awareness in populations with equal access to care, we might conclude that race/ethnicity is an independent factor that potentially magnifies poor baseline stroke awareness. Further, poor stroke awareness appears to exist among individuals from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds whether they have history of prior stroke or are absent of stroke history.4,5,8,10,11

Our secondary findings provide evidence that race/ethnicity is an independent predictor of poor stroke awareness. Being Hispanic/other or older than 65 years of age were independent correlates of poor recognition of the five collective warning signs of stroke and taking first appropriate action to call 911 for treatment. In multivariate models, race/ethnicity emerged as an independent predictor of poor stroke awareness. Support for this hypothesis is found in an article by Pancioli and colleagues, who also identified race/ethnicity as a predictor of poor stroke awareness.5 Older age (>65 years) was also associated with poor stroke awareness, as noted in previous studies of stroke awareness.5,10

Currently, there is less agreement regarding primary predictors of poor stroke awareness particularly among individuals at risk for stroke. Weltermann and colleagues examined stroke awareness (stroke symptom knowledge) in 93 stroke patients and 40 family members and volunteers and found that history of prior stroke, age >70, and poor self-reported health status emerged as predictors of poor stroke knowledge.15 While older age,5,10 race,5 and lower levels of education5,10 are frequently associated with poor stroke awareness, sex (male),5,10 hypertension, smoking status, and self-reported poor health status10 have also been reported as independent factors associated with poor recognition of early warning signs of stroke. One significant predictor of greater stroke awareness did emerge: post-high school education. Individuals with >high school education were more likely to recognize the five collective warning signs and take action to call 911.

Improved awareness of early warning signs of stroke among at-risk individuals is critical to national efforts to reduce stroke incidence, mortality, and morbidity. People with prior history of stroke are at great risk for a second stroke, and even though it is generally expected they would have greater stroke awareness and take appropriate action,13 our results do not agree. Therefore, when considering the high likelihood of a second stroke and our observations of poor stroke awareness even among those with prior stroke, current educational strategies are not achieving their desired outcome. In that regard, novel educational programs and strategies must be considered that are sensitive to the multidimensional (i.e., race, age, education, stroke risk factors) risk factor profiles that many at-risk individuals exhibit.

Improvements in public awareness of stroke are urgently needed because poor awareness of the complex presentation of stroke (all five symptoms) has a number of consequences. First and foremost, poor recognition of early warning signs can result in delays in seeking proper medical care.22–24 Delays in seeking care are associated with greater stroke severity, higher stroke mortality, and greater post-stroke disability.25–28 The effectiveness of stroke medications is then decreased when treatment is delayed. Despite significant improvements in medications designed to minimize stroke severity and associated long-term disability, patients who do not immediately recognize stroke warning signs and seek urgent care at symptom onset are less likely to have positive stroke outcomes.29

A number of strategies have been proposed for educational programs designed to improve stroke awareness. These include: (1) emphasize early recognition of all five primary warning signs collectively, as well as activation of the 911 system,30 (2) reinforce the link between presence of symptoms and recognition that a stroke is occurring,14 and (3) stress the need to call 911 to facilitate early intervention. Targeted educational programs must be designed for specific groups at highest risk for stroke.14 Programs designed for individuals with prior history of stroke should also stress the link between their current risk factor (prior stroke) and the likelihood of stroke reoccurrence. Educational programs for patients with history of prior stroke should include comprehensive and integrated information concerning stroke risk factors, stroke reoccurrence rates, and causes of future strokes.31

In our work, stroke awareness among racial/ethnic minorities absent of stroke risk factors, with stroke risk factors, and with prior history of stroke is surprisingly similar. These findings suggest that current strategies are not favored by racial/ethnic minorities, and that current levels of stroke awareness are not acceptable as long as stroke continues to occur at a substantially higher rate among minority groups. In addition to general education programs for the public, programs should be designed specifically for racial/ethnic minorities.

To support these efforts, future studies are needed to determine optimal educational strategies and the most appropriate mediums (TV, radio, and Internet) for racial/ethnic minorities. Racially/ethnically sensitive programs should include the patients at risk and their family, friends, and primary care physicians. Programs should be offered through community-based centers providing care to large numbers of minority patients, churches, and social organizations as appropriate.32 Support for educational programs should be sought from community leaders and provided in community-based venues that are most recognized and valued by racial/ethnic minorities.

Limitations

The results of this study should be considered in light of the following potential limitations. First, telephone surveys may yield biased estimates because of exclusion of households without telephones. However, studies have established the validity of the BRFSS telephone survey.33,34 Second, important factors that may affect knowledge of stroke risk factors were not measured in this study, including health literacy, quality of stroke education, cultural appropriateness of educational materials, and attendance at educational programs. Third, the Hispanic/other group included individuals who classified themselves as Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native. Additional studies including adequate samples of these ethnic groups for analyses would provide additional insights into stroke awareness for these groups. Additionally, inclusion of individuals who do not speak English as a primary language should be included in future studies, as lack of literacy decreases the likelihood of benefiting from public health campaigns to improve stroke awareness. These factors may provide additional explanations for the findings of the study and should be evaluated in future studies. Finally, the use of close-ended questions may have influenced some responses relative to more open-ended questions.6

CONCLUSION

A high percentage of individuals with prior history of stroke recognize individual stroke warning signs, but few recognize all five stroke warning signs and would take appropriate action to call 911. The lowest rates of recognition of the multiple signs associated with stroke and taking appropriate action exist among racial/ethnic minorities: black respondents and Hispanic/other respondents. Targeted interventions are needed to improve stroke awareness among racial/ethnic minorities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institutes of Health (US) Know stroke. Know the signs. Act in time. 2008. [cited 2008 Jan 30]. NIH Publication No. 02-4872. Available from: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/stroke/knowstroke.htm.

- 3.National Institutes of Health (US) What you need to know about stroke. 2008. [cited 2008 Jan 30]. NIH Publication No. 04-5517. Available from: URL: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/stroke/stroke_needtoknow.htm.

- 4.Greenlund KJ, Neff LJ, Zheng ZJ, Keenan NL, Giles WH, Ayala CA, et al. Low public recognition of major stroke symptoms. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:315–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pancioli AM, Broderick J, Kothari R, Brott T, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, et al. Public perception of stroke warning signs and knowledge of potential risk factors. JAMA. 1998;279:1288–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe AK, Frankel MR, Sanders KA. Stroke awareness among Georgia adults: epidemiology and considerations regarding measurement. South Med J. 2001;94:613–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kothari R, Sauerbeck L, Jauch E, Broderick J, Brott T, Khoury J, et al. Patients' awareness of stroke signs, symptoms, and risk factors. Stroke. 1997;28:1871–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.10.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider AT, Pancioli AM, Khoury JC, Rademacher E, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, et al. Trends in community knowledge of the warning signs and risk factors for stroke. JAMA. 2003;289:343–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkadry MG, Wilson C, Nicholson D. Stroke awareness among rural residents: the case of West Virginia. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;42:73–92. doi: 10.1300/J010v42n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves MJ, Hogan JG, Rafferty AP. Knowledge of stroke risk factors and warning signs among Michigan adults. Neurology. 2002;59:1547–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000031796.52748.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris A, Robertson RM, Fabunmi R, Mosca L, American Heart Association. American Stroke Association American Heart Association and American Stroke Association national survey of stroke risk awareness among women. Circulation. 2005;111:1321–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157745.46344.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blades LL, Oser CS, Dietrich DW, Okon NJ, Rodriguez DV, Burnett AM, et al. Rural community knowledge of stroke warning signs and risk factors. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alkadry MG. An ounce of prevention keeps stroke away: a West Virginia study of awareness of stroke risks and symptoms. West Virginia Public Affairs Reporter. 2005;22:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll C, Hobart J, Fox C, Teare L, Gibson J. Stroke in Devon: knowledge was good, but action was poor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:567–71. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.018382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weltermann BM, Homann J, Rogalewski A, Brach S, Voss S, Ringelstein EB. Stroke knowledge among stroke support group members. Stroke. 2000;31:1230–3. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Stroke Association. Recovery after stroke: recurrent stroke. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System user's guide. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0. College Station (TX): Stata Corp.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon SS, Byles J. Perceptions of stroke in the general public and patients with stroke: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2002;324:1065–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7345.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis C, Egede L. Racial-ethnic differences in stroke awareness among veterans. Presented at the HSR&D National Meeting; 2007 Feb 21–23; Arlington, Virginia

- 21.Wilson NJ, Kizer KW. The VA health care system: an unrecognized national safety net. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:200–4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder EB, Rosamond WD, Morris DL, Evenson KR, Hinn AR. Determinants of use of emergency medical services in a population with stroke symptoms: the second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) study. Stroke. 2000;31:2591–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris DL, Rosamond WD, Hinn AR, Gorton RA. Time delays in accessing stroke care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:218–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams JE, Rosamond WD, Morris DL. Stroke symptom attribution and time to emergency department arrival: the delay in accessing stroke healthcare study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:93–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacy CR, Suh DC, Bueno M, Kostis JB. Delay in presentation and evaluation for acute stroke: Stroke Time Registry for Outcomes Knowledge and Epidemiology (S.T.R.O.K.E. ). Stroke. 2001;32:63–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith MA, Doliszny KM, Shahar E, McGovern PG, Arnett DK, Luepker RV. Delayed hospital arrival for acute stroke: the Minnesota Stroke Survey. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:190–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris DL, Rosamond W, Madden K, Schultz C, Hamilton S. Prehospital and emergency department delays after acute stroke: the Genentech Stroke Presentation Survey. Stroke. 2000;31:2585–90. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, Alonzo A, Croft JB, Dracup K, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006;114:168–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Awareness of stroke warning signs—17 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(17):359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caplan LR. Prevention of strokes and recurrent strokes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:716. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.6.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacco RL. Preventing stroke among blacks: the challenges continue. JAMA. 2003;289:3005–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowlin SJ, Morrill BD, Nafziger AN, Lewis C, Pearson TA. Reliability and changes in validity of self-reported cardiovascular disease risk factors using dual response: the behavioral risk factor survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:511–7. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shea S, Stein AD, Lantigua R, Basch CE. Reliability of the behavioral risk factor survey in a triethnic population. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:489–500. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]