Abstract

The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT), widely distributed in the central nervous system (CNS), is involved in a large variety of physiological functions. In several brain regions 5-HT is diffusely released by volume transmission and behaves as a neuromodulator rather than as a “classical” neurotransmitter. In some cases 5-HT is co-localized in the same nerve terminal with other neurotransmitters and reciprocal interactions take place. This review will focus on the modulatory action of 5-HT on the effects of glutamate and γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA), which are the principal neurotransmitters mediating respectively excitatory and inhibitory signals in the CNS. Examples of interaction at pre-and/or post-synaptic levels will be illustrated, as well as the receptors involved and their mechanisms of action. Finally, the physiological meaning of neuromodulatory effects of 5-HT will be briefly discussed with respect to pathologies deriving from malfunctioning of serotonin system.

Key Words: Serotonin, neuromodulation, GABA, glutamate, cognition, nociception, motor control

INTRODUCTION

The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxy-tryptamine, 5-HT) is involved in the regulation of basic physiological functions such as hormone secretion [69], sleep-wake cycle [181], motor control [85], immune system functioning [133], nociception [47], food intake [122] and energy balance [74]. In addition, 5-HT participates to higher brain functions, such as cognition and emotional states, by modulating synaptic plasticity [52] and, as recently discovered, neurogenesis [42, 62, 83].

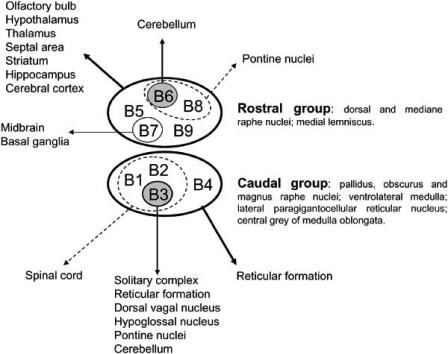

Serotonergic neurons of the CNS are localized in clusters within the raphe nuclei, central gray and reticular formation [68, 84] and have been classified into nine groups named B1-B9 [29] (Fig. 1). Nerve fibers arising from the caudal groups of serotonergic neurons (B1-B4) form a descending system directed to the spinal cord and also project to cerebellum, pontine and midbrain structures, whereas ascending fibers originate from the rostral groups of serotonergic neurons (B5-B9) and innervate almost all brain areas.

Fig. (1).

Serotonin system. Principal groups of serotonergic neurons in the CNS and their projection sites.

Serotonin receptors were initially divided in two main classes named 5-HT1 and 5-HT2, displaying respectively nanomolar and micromolar affinity for 5-HT [150]. Five other 5-HT receptor types have since been characterized and named 5-HT3 [16], 5-HT4 [45], 5-HT5, 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 [64, 176] and within each receptor family different subtypes exist. To date, fourteen subtypes of serotonin receptors have been cloned; the localization, pharmacological profile [9, 79], intracellular signaling pathways [79, 140, 149], modulatory effects on membrane ion currents [12] and physiological functions [9, 193] of the principal serotonin receptor subtypes are summarized in Table 1. With the exception of the 5-HT3 receptor, which is a ligand-gated ion channel, all the other 5-HT receptor subtypes are metabotropic G-protein-coupled receptors and modulate an intracellular second messenger system. In particular, subtypes belonging to the 5-HT1 family are coupled to a G-protein of the Gi/o type and reduce adenylate cyclase activity; 5-HT2 receptor subtypes activate phospholypase C, thus stimulating PI hydrolysis and intracellular Ca2+ release; 5-HT4, 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 are instead positively coupled to adenylate cyclase (through a Gs) and increase cAMP levels. The final effect on membrane potential is hyperpolarizing for 5-HT1A receptors and depolarizing for most other subtypes, with a fast depolarization mediated by 5-HT3 receptors and a slow depolarization mediated by 5-HT2A-B, 5-HT4 and 5-HT7 receptors. 5-HT2C were shown to exert either hyperpolarizing [25, 37] or depolarizing effects [48, 190] in distinct areas.

Table 1.

Serotonin Receptor Subtypes. 5-HT receptors have been grouped into seven principal classes, named 5-HT1 to 5-HT7; for each subtype, the table indicates the pharmacological characteristics, the localization, the intracellular action mechanism and final effect on neuronal excitability, the physiological function in which the receptor is involved and the pathologies deriving from its malfunctioning.

| Receptor | Localization | Agonists | Antagonists | Intracellular second messenger | Membrane effects | Physiological function | Malfunctioning pathologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | Dorsal raphe; Hippocampus | 8-OH-DPAT buspirone gepirone |

NAN 190 MDL 73005EF WAY 100635 |

Gi/o ↑↓ camp ↑ PI turnover* |

Hyperpolarization (increase in gK; decrease in gCa) | Autoreceptor; modulation of release of other neurotransmitters modulation of anxiety | Anxiety; depression |

| 5-HT1B | Hippocampus; Striatum; Substantia nigra; Raphe nuclei; Cerebellum; Frontal cortex; Cerebral arteries | Sumatriptan | GR55562 SB 216641 SB 272183 |

- | - | Nerve terminal autoreceptor; modulation of release of other neurotransmitters | migraine |

| 5-HT1D | Dorsal raphe; Human heart | Sumatriptan PNU 109291 |

BRL 15572 | - | - | autoreceptor | migraine |

| 5-HT2A | Cortex; Basal ganglia; Peripheral tissues | DOI DOB |

Ketanserin MDL 100907 Cinanserin Mianserin Methysergide |

Gq/11 ↑ PI turnover |

Depolarization (decrease in gK) | Possibile role in learning and memory | Psychiatric disorders |

| 5-HT2B | Cerebellum; lateral septum; hypothalamus; amigdala; cardiac valves | BW 723C86 | SB 200646 SB 204741 |

Gq/11 ↑ PI turnover |

- | Food intake; behaviour | Anxiety; feeding disorders; cardiac valvulopathies |

| 5-HT2C | Choroid plexus; Hippocampus Habenula Substantia nigra Raphe nuclei |

Ro 600175 | Mianserin Methysergide Mesulergine |

Gq/11 ↑ PI turnover |

Depolarization or hyperpolarization in distinct neurons | Food intake; neuroendocrine regulation | Feeding disorders; Cognitive impairment |

| 5-HT3 | Olfactory bulb Cerebral cortex Hippocampus Amygdala Hypothalamus Solitary tract nucleus |

2-methyl-5-HT SR 57227 |

ICS 205930 Zacopride Ondansetron Granisetron Tropisetron |

None: direct gating of channel | Fast depolarization (increase in gNa and gK) | Pre-synaptic modulation of transmitter release | Anxiety; Schizophrenia; Cognitive impairment |

| 5-HT4 | Colliculi Hippocampus Peripheral tissues |

Renzapride BIMU 8 RS 67506 ML 10302 |

GR 113808 SB 204070 |

Gs ↑ cAMP |

Slow depolarization (decrease in gK) | Modulation of transmitter release; memory enhancement | Neurodegenerative diseases; Cardiac arrhythmia |

| 5-HT6 | Striatum Amygdala N. accumbens Hippocampus Cortex Olfactory tubercle |

Ro 630563 SB 271046 SB 357134 |

Gs ↑ cAMP |

- | Modulation of acetylcholine transmission | Cognitive disfunctions (Alzheimer) | |

| 5-HT7 | Cerebral cortex; Thalamic nuclei; hypothalamus; limbic structures | 8-OH-DPAT | SB 258719 SB 269970 |

Gs ↑ cAMP |

Slow depolarization (increase of Ih) | Control of circadian rhythms; Thermoregulation Mood and behaviour | Affective disorders; Migraine; Nociception |

Some of the cloned 5-HT receptors (5-ht1E, 5-ht1F, 5-ht5A, and 5-ht5B) are indicated in lower case to denote that their endogenous expression and physiological function still have to be found (Table 2); no selective ligand for these receptors is yet available, but the mRNA coding for each of them has been localized in discrete brain areas by in situ hybridization [79].

Table 2.

Putative Serotonin Receptor Subtypes. 5-HT1E, 5-HT1F and 5-HT5 (5A and 5B) receptors have been cloned and their mRNA has been localized in various CNS ares by in situ hybridization; the existence of native counterparts of these receptors and their physiological function still has to be proved.

| Receptor | Ligands | Localization (mRNA) | Second messenger | Hypotheses on function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-ht1E | - | human frontal cortex; putamen | Gi/o ↓cAMP* |

- |

| 5-ht1F | LY 334370 sumatriptan |

Dorsal raphe Hippocampus Cortex Striatum Thalamus Hypothalamus |

Gi/o ↓cAMP* |

autoreceptor |

| 5-ht5A | - | Gi/o | ||

| 5-ht5B | - | None identified |

In many brain regions 5-HT receptors have been localized on neurons that do not receive a direct serotonergic innervation; in parallel, 5-HT fibers often lack typical synaptic contacts with post-synaptic neurons [35, 180]. Such a mismatch between serotonergic fibers and post-synaptic 5-HT receptors has suggested that 5-HT in the CNS may preferentially use volume transmission and behave as a neuromodulator rather than as a “classical” neurotransmitter [3, 20, 21, 158]. As a matter of fact, a large number of studies report that 5-HT is able to modulate excitatory and inhibitory effects respectively mediated by glutamate and GABA; some examples will be illustrated below.

MODULATORY ACTION OF SEROTONIN ON GLUTAMATE- AND GABA- MEDIATED TRANSMISSION

Modes of Interaction

5-HT differently modifies glutamate- and GABA- mediated effects, acting on distinct 5-HT receptor subtypes. At a pre-synaptic level, 5-HT can modulate neurotransmitter release: for example, in various brain regions glutamate release is reduced by 5-HT1A [162, 164, 177], 5-HT1B [13, 130, 151, 167] and 5-HT6 receptors [31]. Similarly, pre-synaptic inhibition of GABA release is mediated by 5-HT1A [90, 95, 96] and 5-HT1B receptors [88, 117]. By activation of 5-HT3 receptors, instead, 5-HT stimulates the release of either glutamate [7, 57, 185] or GABA [90, 96, 179]. Also 5-HT2 receptors were shown to stimulate GABA release [2] and to either increase [2, 72, 177] or reduce [118] glutamate release in distinct structures.

Concerning GABA release, another action of 5-HT consists in modulating the excitability of GABAergic interneurons; on this aspect, detailed studies have been performed in the hippocampus. Serotonergic fibers from dorsal raphe selectively target a subset of hippocampal interneurons specifically involved in GABAB-mediated feedforward inhibition [55, 56]. In interneurons from stratum lacunosum-molecolare of the CA1 region, the amplitude of a T-type low threshold voltage-dependent Ca2+ current, which is responsible for rhythmic oscillations of membrane potential, is enhanced by 5-HT and reduced by a GABAB agonists [54]. Concerning the role of different subtypes of 5-HT receptors, it has been shown that GABA release from CA1 interneurons is inhibited by 5-HT1A receptors [90, 163] and enhanced by 5-HT2 [166] and 5-HT3 receptors [90, 121, 157, 179]. An important issue is that a very large heterogeneity exists among hippocampal interneurons [148]: as a matter of fact, as many as 16 different types have been characterized based on their location and morphology; besides, hippocampal interneurons also differ with respect to colocalization of GABA with various peptides, expression of calcium binding proteins, expression of membrane ion channels, discharge patterns and responsiveness to neurotransmitters. In fact, the activity of hippocampal interneurons is differentially modulated by 5-HT, noradrenaline, acetylcholine acting on muscarinic receptors and glutamate acting on metabotropic receptors, following at least 25 different response patterns. Since each type of interneuron probably controls a peculiar function (for example the generation of action potentials from pyramidal neurons, the integration of input signals or the modulation of local inhibitory networks), the authors postulated that the role of modulating neurotransmitters, among which 5-HT, is to switch between functions and thus change hippocampal computation [148].

Similarly to the hippocampus, modulation of GABA release from interneurons (mainly inhibition by 5-HT1A receptors and stimulation by 5-HT2 and/or 5-HT3 receptors) has also been observed in other areas, among which dentate gyrus [132, 152], enthorinal cortex [40, 165], piriform cortex [115], frontal and anterior cingulate cortex [192].

Glutamate- and GABA-mediated effects can also be modulated by 5-HT at a post-synaptic site; the mechanisms of interaction have been elucidated in some cases and include: 1) recruitment of receptors on the post-synaptic membrane [104]; 2) modulation of receptor function by promoting its phosphorylation [49, 103, 191]; 3) effects converging on a common signaling pathway, such as a G protein [6, 144], adenylate cyclase [169] or phospholipase C [147]; 4) modulation of a common membrane ion channel [54, 169]; 5) effects on distinct ion channels, reciprocally influencing membrane potential and neuronal excitability [2, 46, 154, 155, 161].

The following paragraphs will illustrate in more details some examples of 5-HT modulation on glutamate- and GABA-mediated transmission, especially with respect to the physiological functions of the brain areas where such modulation occurs.

Modulation of Glutamate Transmission

Glutamate is the most widely diffused excitatory amino acid in the central nervous system, activating three major types of ionotropic receptors, namely N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and 2-carboxy-3-carboxymethyl-4-isopropenylpyrrolidine (kainate) receptors, and three main groups of metabotropic receptors (counting eight subtypes named mGluR1-8) [93].

A recent article points out that co-transmission of glutamate and monoamines is a very frequent phenomenon in the CNS [178]. This view is supported by the finding that raphe neurons, the main source of serotonergic fibres projecting to almost all brain regions, are immunopositive for glutamate [138, 146] as well as for phosphate-activated glutaminase (PAG), an enzyme involved in glutamate metabolism [89], and contain the vescicular glutamate transporter VGLUT3 [65]. When grown in microcultures, approximately 60% of serotonergic raphe neurons evoke AMPA/kainate-mediated excitatory post synaptic potentials (EPSPs), indicating that most of these neurons in addition to 5-HT use glutamate as a co-transmitter [87].

Modulation of glutamate transmission by 5-HT has been described in several CNS regions, especially in those controlling cognition, nociception and motor functions.

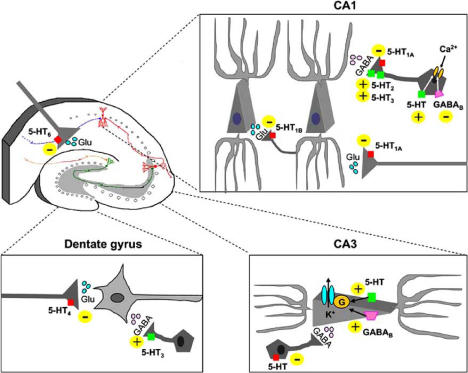

Among the structures involved in learning and memory, in the hippocampus 5-HT-glutamate interaction has been extensively explored. One of the first observations was that the effects mediated by NMDA and 5-HT2 receptors converge on the same signal transduction mechanism (phosphatidylinositol breakdown) [59]. Later, it was reported that 5-HT suppresses long term potentiation (LTP) in hippocampal slices by preventing the activation of NMDA receptors and the enhancement of AMPA-mediated currents that lead to LTP induction [171]. The hippocampus contains several subtypes of serotonin receptors, namely 5-HT1A [160, 174], 5-HT1B [4, 130], 5-HT2 [17, 28], 5-HT3 [116, 132], 5-HT4 [5, 160], 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 [73], many of which modulate glutamate-mediated transmission acting at different levels. In the CA1 region, pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors reduce glutamate release from Schaffer collaterals to CA1 pyramidal neurons [162] (Fig. 2). 5-HT1B receptors are instead located on the axons terminals of CA1 pyramidal neurons [4]; their activation inhibits local glutamate release, depressing especially the AMPA/kainate component of excitatory transmission to neighboring CA1 pyramidal neurons and to local interneurons [130, 131]. 5-HT1B receptors also reduce glutamate release from CA1 fibers in the subicular cortex [13]. Based on these data, it was proposed that the memory impairment observed after a treatment with 5-HT1B agonists is probably caused by a reduction of excitatory neurotransmission in circuits involving the hippocampus [129].

Fig. (2).

Modulation of glutamate- and GABA-mediated transmission by 5-HT in the hippocampus. In the CA1 region, pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors on Schaffer collaterals reduce glutamate release to pyramidal neurons [162]. 5-HT1B receptors, located on axon terminals from pyramidal neurons and on their recurrent collaterals, inhibit glutamate release to neighboring pyramidal neurons and to local interneurons [130, 131]. The release of GABA from CA1 inhibitory interneurons is stimulated by 5-HT2 [101, 166] and by 5-HT3 receptors [90, 121, 157, 163, 179] and inhibited by 5-HT1A receptors [90, 157, 163]. 5-HT and GABAB receptors respectively increase and decrease T-type Ca2+ current on interneurons from stratum lacunosum-moleculare [54]. In dentate gyrus, 5-HT4 receptors inhibit glutamate-mediated transmission [97], whereas 5-HT3 receptors stimulate GABA release from interneurons [121, 152]. In CA3 pyramidal neurons, 5-HT inhibits GABAB -mediated IPSCs acting both pre- and post-synaptically [145]; 5-HT and GABAB receptors cooperate in increasing a hyperpolarizing outward potassium (K+) current [169]. A decrease in glutamate release mediated by 5-HT6 receptors has been measured by microdialysis in the whole dorsal hippocampus [31]. Note: this figure represents a simplified scheme and does not account for the different subtypes of hippocampal interneurons.

On the other side, 5-HT2A receptors stimulate glutamate release from fibers arising in the CA1 and CA3 regions and directed to dorsolateral septal nucleus [72].

Concerning 5-HT4 receptors, various modulatory effects on excitatory transmission have been observed in dentate gyrus by two distinct research groups using a similar experimental protocol (recording of evoked field potentials in dentate gyrus of freely moving rats): 5-HT4 receptor activation induced either a decrease [97] or no effect [114] on basal synaptic transmission. Both studies concur however that 5-HT4 receptor activation modulated LTP as well as depotentiation, a low-frequency stimulation-induced reversal of LTP, suggesting their role in metaplasticity, a high order level of synaptic plasticity related to activation of NMDA receptors and subsequent Ca2+ entry prior to stimulation protocols that induce LTP or LTD [1].

Another 5-HT receptor modulating hippocampal glutamate transmission is the 5-HT6 subtype, the activation of which tonically inhibits glutamate release in dorsal hippocampus, as shown by microdialysis experiments in vivo [31].

In addition, hippocampal circuits are modulated by 5-HT through enthorinal cortex, the region sending one of the main inputs to hippocampus, where pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors reduce glutamate release [164].

A reciprocal interaction between serotonin and glutamate also occurs in frontal cortex, a brain area responsible for working memory and selective attention, thus playing a primary role in cognition. In this region, similarly to results obtained in dorsal hippocampus, glutamate release is tonically inhibited by 5-HT6 receptors [31]. At the same time, 5-HT is able to counteract a number of effects mediated by NMDA receptors: for example, NMDA-induced stimulation of 5-HT release from fibers originating in raphe nuclei is inhibited by 5-HT autoreceptors belonging to the 5-HT1 family [51]. Activation of NMDA receptors in frontal cortex by microdialysis stimulates the release of glutamate in the striatum while reducing local glutamate release, and such effects are inhibited respectively by 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors [26, 41]. NMDA-mediated NO-synthase activation and cGMP formation in cultured cortical neurons is inhibited by 5-HT2 receptor agonists [60]; the same effect was observed in cortical slices after application of the 5-HT1B-D agonists sumatriptan and zolmitriptan [172].

Differing from frontal cortex, where many glutamatemediated effects are contrasted by 5-HT, in prefrontal cortex 5-HT enhances glutamate transmission by both pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms: 5-HT2A receptor activation increases glutamate release and enhances the amplitude of glutamatergic EPSCs by inducing a sub-threshold sodium current in the apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons [2].

One of the best known functions of 5-HT in the nervous system is the control of nociception, exerting either anti- or pro-nociceptive effects depending on the type of 5-HT receptor and on its site of action [8, 50, 58, 63, 125]. With respect to glutamate-mediated transmission, modulatory effects of 5-HT have been observed in the thalamus, a structure involved in the integration of sensory inputs including pain stimuli, and in the dorsal horn of spinal cord, an important gating region for nociceptive transmission. In neurons from ventrobasal thalamus, 5-HT enhances both NMDA- and non-NMDA-mediated effects; such action of 5-HT, however, is indirectly mediated by an increase of Ih, a hyperpolarization-activated Na+/K+ current contrasting inhibitory inputs [46, 161].

In spinal dorsal horn, descending serotonergic fibers arising from raphe nuclei exert a strong modulation on the input from primary sensory afferents, inducing either inhibition or enhancement of glutamate transmission through distinct 5-HT receptors. As a matter of fact, a reduction of synaptic currents is mediated by 5-HT1A receptors [78], which depress the responsiveness of dorsal horn neurons to NMDA [110, 135], whereas an enhancement is induced by 5-HT2 receptors by switching silent glutamatergic synapses into functional ones [105]. In particular, 5-HT2-receptor activation stimulates the recruitment of post-synaptic AMPA receptors; such effect is strictly dependent on a PDZ protein (Post-synaptic density 95/Disc-large/Zonula occludens-1) [104], a membrane protein involved in various functions among which the targeting of receptors to a specific subcellular compartment [63, 71]. 5-HT2–mediated enhancement of synaptic currents in spinal dorsal horn has been predominantly observed during development. Vice versa, in adult animals 5-HT exclusively inhibits synaptic responses; however, 5-HT inhibitory effect can be turned into a stimulation by elevating intracellular cAMP levels; again, 5-HT action mechanism is based on recruiting functional AMPA responses in previously pure NMDA (silent) synapses [184]. Thus, in spinal dorsal horn of adult animals 5-HT2 receptors can mediate either facilitating or inhibitory effects on glutamate-mediated transmission depending on the intracellular level of cAMP, a condition that can be modified by a number of other neurotransmitters modulating adenylate cyclase activity.

5-HT-glutamate interaction in the spinal cord, besides controlling pain transmission, plays a role in motor control. At a cellular level, 5-HT is able to increase glutamate-induced excitability of spinal motoneurons [77, 82, 168, 187]. Consistently, an experimentally-induced decrease in 5-HT levels in ventral horn was found to suppress postural muscle tone, an effect that is likely to contribute to the muscle atonia occurring during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [98]. In addition, activation of spinal 5-HT receptors modulates some typical NMDA-receptor mediated behaviors [128].

5-HT is able to enhance glutamate-mediated excitation of motoneurons in some cranial motor nuclei, among which facial [119] and trigeminal nucleus [80]. In substantia nigra, another region controlling voluntary movement, post-synaptic 5-HT2A and 5-HT4 receptors located on dopaminergic neurons selectively inhibit the mGluR-mediated component of glutamate response; since mGluR effect consisted in a slow inhibitory outward current, the action of 5-HT shifted neuronal response to glutamate towards excitation [147].

In our laboratories, we have studied the modulatory action of 5-HT in vestibular nuclei and in the red nucleus of mesencephalon, both structures involved in motor functions. Microiontophoretic applications of 5-HT in the lateral vestibular nucleus increased neuronal firing rate; the response to 5-HT was attenuated when neuronal background firing was increased by glutamate co-application, suggesting that 5-HT- and glutamate- mediated effects, occluding each other, might converge on a common mechanism [109]. The interplay between 5-HT and glutamate in vestibular nuclei involved different receptor subtypes: the prevailing action of serotonin was a depression of the NMDA component of glutamate response and such effect was mediated by 5-HT2 receptors. Conversely, an enhancement of both NMDA and non-NMDA receptor-mediated responses was observed in a minority of cases and was mediated by 5-HT1A receptors [106]. As to the functional consequences of 5-HT effect, changing the responsiveness of vestibular neurons to glutamate might affect postural balance and ocular movements, the main functions controlled by vestibular nuclei.

In the red nucleus 5-HT depressed glutamate-induced excitation; 5-HT effect was mediated by 5-HT1A receptors and was mostly directed to non-NMDA responses [107].

Still concerning motor function, inhibition of glutamate-mediated effects by serotonin has been described the cerebellum, where 5-HT depresses glutamate-induced excitation of Purkinje cells [75, 102]. Consistently, another study shows that activation of 5-HT2 receptors reduces glutamate release from synaptosomes derived from mossy fibers [118]. In neurons of deep nuclei from cerebellar slices, 5-HT decreased responses to glutamate, quisqualate and NMDA, probably acting at a post-synaptic level [61].

Modulation of glutamate transmission by 5-HT has also been observed in other brain areas involved in different functions. For example, in tractus solitarius nucleus [7], dorsal vagal motor nucleus [185] and area postrema [57] 5-HT stimulates glutamate release by activation of pre-synaptic 5-HT3 receptors. In suprachiasmatic nucleus, pre-synaptic 5-HT1B receptors inhibit retinal input [151] whereas 5-HT7 receptors reduce glutamate effects at a post-synaptic level [155]; by these effects, serotonin changes neuronal responsiveness to light stimuli and participates to the regulation of circadian rhythms.

Modulation of GABA-Mediated Transmission

γ-Amino-butyric acid (GABA) is the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS and activates three main receptor families: GABAA and GABAC receptors are ligand-gated ion channels carrying a chloride current [14], whereas GABAB are metabotropic G-protein coupled receptors that reduce neuronal excitability mainly by modulating K+ and/or Ca2+ channels [139]. Immunohistochemical data indicate the presence of GABA and serotonin in the same neurons in raphe nuclei [10] and in neurons of medulla oblongata projecting to the spinal cord [126], although colocalization is limited to a small extent [127, 170].

GABA-mediated inhibitory transmission can be strongly modulated by 5-HT: such modulation, in parallel with 5-HTglutamate interactions, has been observed in structures involved in learning and memory, sensory processing, nociception and motor control.

In the hippocampus, as already mentioned, 5-HT is able to modulate GABA release from specific subsets of interneurons; besides, post-synaptic interactions between 5-HT and GABAB receptors have been described (Fig. 2). In CA3 pyramidal neurons, 5-HT selectively depresses the GABAB component of GABA-mediated inhibitory post synaptic potential (IPSP) [145]; in particular, 5-HT and GABAB receptors interact by increasing a hyperpolarizing inwardly rectifying potassium current on CA3 neurons [6, 144]. The mechanism of this interaction (also involving mGluR, adenosine and somatostatin receptors) has been investigated in details [169]: when 5-HT and the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen were used at saturating concentration, co-application induced occlusive effects, indicating a common action mechanism; however at sub-saturating concentrations effects were supra-additive, suggesting cooperation through distinct mechanisms. The authors proposed that the effects mediated by 5-HT and GABAB receptors probably converge on the same target, such as a G-protein or a common pool of potassium channels; in addition, the existence of separate pools of potassium channels, selectively modulated by each neurotransmitter, might account for cooperation [169].

In basolateral amygdala [96], another brain region involved in cognition and mood, 5-HT3 receptor activation enhances GABA release from interneurons.

In pyramidal neurons from prefrontal cortex, both 5-HT2 and 5-HT4 receptors modulate post-synaptically GABAA-mediated effect [49]. In particular, 5-HT2 receptors, by activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and of its anchoring protein RACK1 (receptor for activated C kinase), promote a phosphorylation of GABAA receptors which ultimately reduces GABAA–mediated Cl- currents. Conversely, 5-HT4 receptors are able to exert a dual modulation on GABAA-mediated current depending on protein kinase A (PKA) activation level: 5-HT4 receptors either enhance or depress GABAA current respectively with a low or high basal PKA level. As a possible explanation, it was suggested that different degrees of PKA activity may induce phosphorylation of distinct β subunits of the GABAA receptor, namely a β3 subunit (reducing GABAA receptor function) at low PKA levels and additionally a β1 subunit (leading to an increase of GABAA-mediated current) at high PKA level [49]. The authors also showed that the amount of PKA-mediated phosphorylation increased with neuronal depolarization, providing an example of how 5-HT4 receptors can dynamically regulate GABA-ergic transmission in an activity-dependent manner: an increase in neuronal firing, increasing PKA levels, would enhance GABAA-mediated inhibition, providing a negative feedback control; however when 5-HT4 receptors are also activated, 5-HT4-mediated modulation of GABAA current is switched from enhancement to reduction, which creates a “locked” loop reinforcing neuronal activity [22]. The 5-HT-mediated modulation of GABA transmission described above can be prolonged by corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF), a neuropeptide regulating physiological reactions to stress, which once again links the neuromodulatory role of serotonin to stress-related cognitive and emotional disorders [175].

5-HT modulates the action of GABA in the thalamus, in periaqueductal grey and in spinal dorsal horn, all structures involved at different levels in sensory and pain transmission. In thalamic nuclei, activation of 5-HT2 receptors stimulates GABA release from dendrites of interneurons with a novel mechanism of action: 5-HT effect involved PLC and an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration that did not depend on Ca2+ release from stores nor on membrane voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, but was instead critically dependent on the TRPC4 channel [134], a membrane cation channel belonging to the recently discovered family of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels whose function, still largely unknown, seems to be either store-operated or receptor-operated Ca2+ channels [182]. By increasing GABA release from dendrites of thalamic interneurons, 5-HT can strengthen local GABAergic inhibition and ultimately modulate thalamic processing of sensory signals [134].

In periaqueductal grey 5-HT exerts a dual control on inhibitory interneurons: GABA release is inhibited by activation of 5-HT1A receptors [95] and is probably stimulated by 5-HT2A receptors, which have been localized on GABAergic neurons [66].

In neurons from spinal dorsal horn, 5-HT2 receptor activation enhances GABAA–induced Cl- current acting through a protein kinase-dependent pathway [103, 183, 191] and activation of 5-HT3 receptors evokes GABA release [91], both effects reinforcing GABA-mediated inhibition.

5-HT-GABA interactions have also been described in structures involved in motor control. In the cerebellum, Lugaro cells, a particular class of inhibitory interneurons exclusively found in cerebellar cortex [99, 123], are generally silent unless in the presence of 5-HT, which to date seems to be the only neurotransmitter activating them. In fact, 5-HT induces a release of GABA from Lugaro cells to Purkinje neurons [38, 39], which are subsequently hyperpolarized by an inhibitory current mediated by GABAA receptors with an unusual pharmacology [33]. By this mechanism, 5-HT indirectly reduces the excitability of Purkinje neurons, thus affecting also the output from cerebellum and its influence on motor function [38].

In the red nucleus (RN), a work from our laboratories shows that 5-HT enhances GABA responses in neurons mostly located in the rostral part of the nucleus and this effect is mediated by activation of 5-HT1A receptors; vice-versa, activation of 5-HT2A receptors depresses GABA-mediated inhibition of rubral neurons mostly located in the caudal part of the nucleus [108]. Thus 5-HT is able to exert a dual control on GABA-ergic inhibition in the RN: in particular, inhibition is reduced by 5-HT in the RN area giving rise to rubro-spinal fibers, and is instead reinforced in RN areas involved in a neural circuit delivering information from substantia nigra to reticular substance. By regulating GABAergic inhibition in the RN, 5-HT modulates rubral output and the functions regulated by the RN, which concern not only motor execution but also, according to some authors [81, 142], the acquisition of conditioned reflexes.

PHYSIOLOGICAL MEANING OF 5-HT MODULATION AND ROLE IN PATHOLOGY

As a general view, the reports above cited indicate that in many brain regions 5-HT induces a decrease of glutamate transmission and a parallel increase in GABA transmission; such a pattern is particularly evident in the hippocampus (Fig. 2), [31, 90, 97, 101, 121, 130, 131, 157, 162, 163, 166, 179], in frontal cortex [31, 192] and in the cerebellum [38, 39, 75, 102]. These data together suggest that, at least in the above mentioned districts, the modulatory action of 5-HT may serve as a “brake” on neuronal excitability.

As above discussed, 5-HT modulates glutamate- and GABA-mediated effects in nervous structures mostly deputed to cognitive functions, pain transmission and motor control. In view of this, it is plausible to speculate that a malfunctioning of 5-HT modulation may participate to the pathogenesis of various diseases, some of which will be briefly illustrated.

Role of 5-HT-Mediated Modulation in Learning and Memory

It is well known that psychiatric disorders such as depression and schizophrenia, causing emotional and cognitive disorders, are related to an alteration of the serotonin system [32, 113, 153, 178]; in these pathologies, some responsibility might be attributed to a disruption of 5-HT-mediated control over glutamate- and GABA-mediated transmission in the hippocampus and frontal cortex [32, 113, 136]. In particular schizophrenia is characterized by changes in synaptic connectivity in the hippocampus, affecting mainly glutamate transmission but also the function of GABAergic neurons [70]. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia have been described as a state of “overattention” due to removal of sensory gating in the hippocampus, a physiological mechanism to which different 5-HT receptors participate, mainly by reducing glutamate-mediated transmission while reinforcing GABA-mediated inhibition (Fig. 2).

Consistently, some drugs effective as anti-psychotics as well as cognition enhancers behave as either antagonists or partial agonists of 5-HT1A receptors [159]. Activation of hippocampal 5-HT1B receptors induces a memory impairment [18], anxiety and a strong behavioral inhibition [17]. In line with this, 5-HT1B knockout mice when confronted with a novel environment showed a less anxious and more explorative behavior [17, 112] and in the Morris water maze acquired a hippocampus-dependent spatial reference memory task more easily than wild-type littermates [19], suggesting that 5-HT1B antagonists might be useful in the treatment of anxiety and improve hippocampus-dependent memory.

Also 5-HT6 receptors, inhibiting glutamate release in hippocampus and frontal cortex [31], have become a promising target for pharmacological treatment of cognitive deficits [159].

5-HT1A and 5-HT2A-C agonists resulted effective in preventing glutamate-induced neurotoxicity on cultured frontal cortex neurons [60]; accordingly, in frontal cortex of freely moving animals an experimentally induced enhancement of glutamate release, which would induce excitotoxic effects and impair attentional performance, can be prevented by blockade of 5-HT2A receptors [26, 60]. 5-HT2A antagonists were found to enhance cognition in schizophrenia [159] and in memory deficits resulting from reduction of glutamate transmission [124]; for these reasons, a pharmacological manipulation of 5-HT2A receptors has been suggested in therapies of cognitive disorders associated with either increased or decreased glutamate-mediated transmission [24, 26].

An interesting review [23] put forward the hypothesis that infantile autism is a hypoglutamatergic disorder based on the following observations: first of all, autism is associated with alterations in brain regions (frontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, cerebellum) mostly containing glutamatergic neurons. Secondly, administration of glutamate antagonists (especially NMDA antagonists) induces a series of symptoms very similar to those of autism, such as distorted sensory perception, memory defects, mood fluctuations, social withdrawal and repetitive movements. A relevant fact is that the typical features of autism are mimicked not only by NMDA antagonists but also by 5-HT2A agonists. As the author suggested, the interplay between glutamate and 5-HT receptors offers new possibilities in the treatment of a glutamate deficit: as a matter of fact, the use of glutamate agonists would induce neurotoxicity and convulsions, whereas it might prove a good strategy to act on 5-HT2A receptors which in turn modulate glutamate-mediated effects [23].

A serotonergic hypothesis to explain the cause of autism is indicated in another just outcome review [186]. Autism is in fact characterized by high levels of blood serotonin, and when this condition is mimicked in laboratory animals most of the typical symptoms of human autism are reproduced. The author suggested that, at an early stage of development (during the first two years of life for humans), circulating 5-HT can penetrate the immature blood brain barrier and diffuse into the brain, inducing a loss of serotonergic fibers and/or an altered production of oxytocin and calcitonin-gene related peptide (CGRP), both involved to some extent in social behavior. In light of the negative control exerted by 5-HT2A receptors over glutamate transmission [23], it is plausible to speculate that chronically high levels of 5-HT in the developing brain might also lead to a hypoglutamatergic condition.

Alzheimer disease (AD), another pathology causing severe cognitive disorders, besides the well-known cholinergic deficits is characterized by altered levels of glutamate and serotonin, as well as of their receptors, in brain regions involved in learning and memory [30, 43, 86, 141]. Again it has been shown that glutamate transmission, which is defective in AD, can be pharmacologically modulated using antagonists of 5-HT1A receptors in cerebral cortex [15, 53] and in the hippocampus [11], suggesting that also AD patients may benefit from a treatment with serotonergic drugs.

Role in Analgesia

5-HT is one of the neurotransmitters used by a descending system controlling pain transmission. In spinal dorsal horn, besides modulating glutamate- and GABA-mediated effects, 5-HT exerts a very complex control, also involving interactions with a large number of other neurotransmitters and peptides [125]. The final effect of 5-HT can be either pro- or anti-nociceptive depending on the receptor type activated [173]. In some cases, various and opposing effects have been described for a single 5-HT receptor subtype; for example activation of spinal 5-HT1A receptors can induce either antinociception or hyperalgesia, an excessive pain response to noxious stimuli [125]. A novel selective agonist of 5-HT1A receptors named F13640 was found to induce hyperalgesia in normal animals, whereas in rats with spinal cord injury the same substance is able to prevent allodynia [189], a condition in which innocuous sensory stimuli are perceived as painful [173].

For 5-HT2 receptors, enhancing glutamate transmission in spinal dorsal horn [105], various effects on pain perception have been reported [125]; however, in general they seem to mediate hyperalgesia and might be implicated in chronic pain [63].

5-HT3 receptor-mediated stimulation of GABA release [91] would suggest for them an antinociceptive function. 5-HT3 receptors, however, are also located on a subpopulation of small-diameter afferent fibers and stimulate excitatory neurotransmission; thus their final effect seems rather to be pro-nociceptive [173]. In fact, the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron was shown to reduce allodynia both in an animal model with spinal cord injury [143] and in human patients suffering from neuropathic pain [120].

5-HT-glutamate interactions also take place in the pathogenesis of migraine. As already cited, the 5-HT1B/1D agonists sumatriptan and zolmitriptan in brain cortex contrast NMDA-induced synthesis of NO, one of the main factors triggering headache [172]. In addition, 5-HT1B/1D/1F receptor agonists modulate glutamate release in trigeminal ganglia, [111] and alleviate pain in patients suffering from cutaneous allodynia associated with migraine by reducing nociceptive transmission pre-synaptically [100]. These results suggests that at least part of the anti-migraine action of triptan serotonin agonists is based on a blockade of glutamate effects.

Role in Motor Control

The modulatory action of 5-HT in cerebellum, vestibular nuclei, basal ganglia, red nucleus and spinal cord participates to motor control and postural balance. As already cited, in the motor system 5-HT either enhances [80, 82, 106, 119, 168, 187] or depresses [61, 75, 102, 106, 107, 118] glutamate-mediated transmission in distinct structures. Also for GABA-mediated transmission either enhancement [39, 44, 108] or decrease [36, 108] by 5-HT have been observed in structures controlling movement.

With respect to glutamate, 5-HT modulation is often directed to NMDA-mediated effects [61, 77, 80, 106], whose function is related to the inhibitory control of movement [188]. Interestingly, recent studies show that impulsive-type behaviours (such as hyperlocomotion and stereotypy) induced by blockade of NMDA receptors can be attenuated by administration of 5-HT2A antagonists [24, 76], suggesting a possible use of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists to normalise NMDA receptor hypofunction.

Some observations also indicate an involvement of the serotonin system in Parkinson disease, a pathology characterized by severe motor deficit due to a disruption of the strio-nigral pathway. In basal ganglia, for example, 5-HT exerts a phasic inhibitory control over GABA synthesis and release [36]. Parkinson patients display a reduced level of striatal serotonin binding sites [30] and transporters [92]; accordingly, the selective 5-HT uptake inhibitor citalopram, associated to L-DOPA treatment, was reported to alleviate both bradykinesia and depressive symptoms [34, 156]. Therefore, a more detailed investigation for the precise role of 5-HT receptors controlling GABA-mediated transmission in basal ganglia might offer new perspectives in the therapy of Parkinson disease.

Other Functions

The modulatory control of 5-HT over glutamate- and/or GABA-mediated transmission also plays a role in other functions, among which the regulation of circadian rhythms [151, 155] and may be involved in pathological states linked to circadian system malfunctioning, such as depression, shift work or jet lag.

5-HT1A and GABAA receptors interact in the ventromedial nucleus of female rat hypothalamus to regulate lordosis and thus modulate sexual behavior [67].

Finally, it should also be mentioned that 5-HT, by interacting with NMDA receptors, is able to enhance ethanol tolerance [94], a condition induced by chronic alcohol consumption and characterized by increased GABAA-mediated effects and decreased glutamate transmission. Evidence exists that alcohol addicts display a decreased level of 5-HT receptors, whereas pharmacological agents activating the serotonin system can effectively reduce ethanol consumption [137].

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In the CNS, 5-HT exerts a very complex modulatory control over glutamate- and GABA-mediated transmission, involving many subtypes of 5-HT receptors and a large variety of effects. Such action is made more complex by the fact that 5-HT interacts with many other neurotransmitters, including the two other monoamines noradrenaline and dopamine which also behave as neuromodulators.

In many cases, the use of combined techniques has revealed in details the action mechanism of neuromodulation by 5-HT. Since a malfunctioning of 5-HT-mediated modulation has been associated with a number of pathologies among which schizophrenia, childhood autism, cognitive and motor deficits, migraine and drug abuse, a deeper knowledge of the 5-HT receptor types involved and of their action mechanism(s) will provide useful strategies in the therapy of such diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Prof. F. Santangelo, Prof. F. Licata and Prof. G. Li Volsi for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. This work was supported by the Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (M.I.U.R.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- 5-HT

5-hydroxy-tryptamine, serotonin

- CNS

Central nervous system

- GABA

γ-amino-butyric acid

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoazolepropionic acid

- PAG

Phosphate-activated glutaminase

- VGLUT3

Vescicular glutamate transporter 3

- EPSP

Excitatory post synaptic potential

- LTP

Long term potentiation

- LTD

Long term depression

- NO

Nitric oxyde

- cGMP

Cyclic guanosine-3′,5′-monophosphate

- PDZ

Post-synaptic density 95/Disc-large/Zonula occludens-1

- Ih

Hyperpolarization-activated ion current

- REM

Rapid eyes movement

- mGluR

Metabotropic glutamate receptor

- IPSP

Inhibitory post synaptic potential

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- RACK1

Receptor for activated C kinase

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- CRF

Corticotrophin releasing factor

- TRP

Transient receptor potential

- TRPC4

Transient receptor potential channel 4

- CGRP

Calcitonin-gene related peptide

- L-DOPA

L-Dihydroxyphenylalanine

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham WC, Bear MF. Metaplasticity: the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19(4):126–30. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin induces excitatory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36(4-5):589–99. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnati LF, Zoli M, Stromberg I, Fuxe K. Intercellular communication in the brain: wiring versus volume transmission. Neuroscience. 1995;69(3):711–26. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ait Amara D, Segu L, Naili S, Buhot MC. Serotonin 1B receptor regulation after dorsal subiculum deafferentation. Brain Res Bull. 1995;38(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade R, Chaput Y. 5-Hydroxytryptamine4-like receptors mediate the slow excitatory response to serotonin in the rat hippocampus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;257(3):930–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrade R, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. A G protein couples serotonin and GABAB receptors to the same channels in hippocampus. Science. 1986;234(4781):1261–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2430334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashworth-Preece MA, Jarrott B, Lawrence AJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine3 receptor modulation of excitatory amino acid release in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius. Neurosci Lett. 1995;191(1-2):75–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardin L, Lavarenne J, Eschalier A. Serotonin receptor subtypes involved in the spinal antinociceptive effect of 5-HT in rats. Pain. 2000;86(1-2):11–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38(8):1083–152. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belin MF, Nanopoulos D, Didier M, Aguera M, Steinbusch H, Verhofstad A, Maitre M, Pujol JF. Immunohistochemical evidence for the presence of gamma-aminobutyric acid and serotonin in one nerve cell. A study on the raphe nuclei of the rat using antibodies to glutamate decarboxylase and serotonin. Brain Res. 1983;275(2):329–39. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boast C, Bartolomeo AC, Morris H, Moyer JA. 5-HT antagonists attenuate MK801-impaired radial arm maze performance in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1999;71(3):259–71. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobker DH, Williams JT. Ion conductances affected by 5-HT receptor subtypes in mammalian neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13(5):169–73. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boeijinga PH, Boddeke HW. Activation of 5-HT1B receptors suppresses low but not high frequency synaptic transmission in the rat subicular cortex in vitro. Brain Res. 1996;721(12):59–65. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bormann J. The ‘ABC’ of GABA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21(1):16–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowen DM, Francis PT, Procter AW, Halliwell JV, Mann DM, Neary D. Treatment strategy for the corticocortical neuron pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1992;32(1) doi: 10.1002/ana.410320121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley PB, Engel G, Feniuk W, Fozard JR, Humphrey PP, Middlemiss DN, Mylecharane EJ, Richardson BP, Saxena PR. Proposals for the classification and nomenclature of functional receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25(6):563–76. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buhot MC. Serotonin receptors in cognitive behaviors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7(2):243–54. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buhot MC, Patra SK, Naili S. Spatial memory deficits following stimulation of hippocampal 5-HT1B receptors in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;285(3):221–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00407-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buhot MC, Wolff M, Benhassine N, Costet P, Hen R, Segu L. Spatial learning in the 5-HT1B receptor knockout mouse: selective facilitation/impairment depending on the cognitive demand. Learn Mem. 2003;10(6):466–77. doi: 10.1101/lm.60203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunin MA, Wightman RM. Paracrine neurotransmission in the CNS: involvement of 5-HT. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22(9):377–82. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunin MA, Wightman RM. Quantitative evaluation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) neuronal release and uptake: an investigation of extrasynaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 1998;18(13):4854–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04854.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai X, Flores-Hernandez J, Feng J, Yan Z. Activity-dependent bidirectional regulation of GABA(A) receptor channels by the 5-HT(4) receptor-mediated signalling in rat prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2002;540(Pt 3):743–59. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlsson ML. Hypothesis: is infantile autism a hypoglutamatergic disorder? Relevance of glutamate - serotonin interactions for pharmacotherapy. J Neural Transm. 1998;105(4-5):525–35. doi: 10.1007/s007020050076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlsson ML, Martin P, Nilsson M, Sorensen SM, Carlsson A, Waters S, Waters N. The 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 is more effective in counteracting NMDA antagonist-than dopamine agonist-induced hyperactivity in mice. J Neural Transm. 1999;106(2):123–9. doi: 10.1007/s007020050144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr DB, Cooper DC, Ulrich SL, Spruston N, Surmeier DJ. Serotonin receptor activation inhibits sodium current and dendritic excitability in prefrontal cortex via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2002;22(16):6846–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06846.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ceglia I, Carli M, Baviera M, Renoldi G, Calcagno E, Invernizzi RW. The 5-HT receptor antagonist M100,907 prevents extracellular glutamate rising in response to NMDA receptor blockade in the mPFC. J Neurochem. 2004;91(1):189–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapin EM, Andrade R. A 5-HT(7) receptor-mediated depolarization in the anterodorsal thalamus. II. Involvement of the hyperpolarization-activated current I(h) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297(1):403–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Bazan NG. Acetaminophen modifies hippocampal synaptic plasticity via a presynaptic 5-HT2 receptor. Neuroreport. 2003;14(5):743–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200304150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlstrom A, Fuxe K. Evidence for the existence of monoamine containing neurons in the central nervous system. I. Demonstration of monoamines in cell bodies of brainstem neurons. Acta Fisiol Scand. 1964;62(232):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Amato RJ, Zweig RM, Whitehouse PJ, Wenk GL, Singer HS, Mayeux R, Price DL, Snyder SH. Aminergic systems in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1987;22(2):229–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson LA, Nguyen HQ, Li P. The 5-HT(6) receptor antagonist SB-271046 selectively enhances excitatory neurotransmission in the rat frontal cortex and hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(5):662–8. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dean B. A predicted cortical serotonergic/cholinergic/ GABAergic interface as a site of pathology in schizophrenia. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28(1-2):74–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean I, Robertson SJ, Edwards FA. Serotonin drives a novel GABAergic synaptic current recorded in rat cerebellar purkinje cells: a Lugaro cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 2003;23(11):4457–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04457.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dell’Agnello G, Ceravolo R, Nuti A, Bellini G, Piccinni A, D’Avino C, Dell’Osso L, Bonuccelli U. SSRIs do not worsen Parkinson’s disease: evidence from an open-label, prospective study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24(4):221–7. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Descarries L, Audet MA, Doucet G, Garcia S, Oleskevich S, Seguela P, Soghomonian JJ, Watkins KC. Morphology of central serotonin neurons. Brief review of quantified aspects of their distribution and ultrastructural relationships. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;600:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb16874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Cara B, Samuel D, Salin P, Kerkerian-Le Goff L, Daszuta A. Serotonergic regulation of the GABAergic transmission in the rat basal ganglia. Synapse. 2003;50(2):144–50. doi: 10.1002/syn.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Matteo V, Cacchio M, Di Giulio C, Esposito E. Role of serotonin(2C) receptors in the control of brain dopaminergic function. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71(4):727–34. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dieudonne S. Serotonergic neuromodulation in the cerebellar cortex: cellular, synaptic, and molecular basis. Neuroscientist. 2001;7(3):207–19. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dieudonne S, Dumoulin A. Serotonin-driven long-range inhibitory connections in the cerebellar cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20(5):1837–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01837.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diez-Ariza M, Ramirez MJ, Lasheras B, Del Rio J. Differential interaction between 5-HT3 receptors and GABAergic neurons inhibiting acetylcholine release in rat entorhinal cortex slices. Brain Res. 1998;801(1-2):228–32. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dijk SN, Francis PT, Stratmann GC, Bowen DM. NMDA-induced glutamate and aspartate release from rat cortical pyramidal neurones: evidence for modulation by a 5-HT1A antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115(7):1169–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Djavadian RL. Serotonin and neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of adult mammals. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2004;64(2):189–200. doi: 10.55782/ane-2004-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doraiswamy PM. The role of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic potential. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2003;3(5):373–8. doi: 10.1007/s11910-003-0019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dumoulin A, Triller A, Dieudonne S. IPSC kinetics at identified GABAergic and mixed GABAergic and glycinergic synapses onto cerebellar Golgi cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21(16):6045–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06045.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumuis A, Sebben M, Bockaert J. BRL 24924: a potent agonist at a non-classical 5-HT receptor positively coupled with adenylate cyclase in colliculi neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;162(2):381–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eaton SA, Salt TE. Modulatory effects of serotonin on excitatory amino acid responses and sensory synaptic transmission in the ventrobasal thalamus. Neuroscience. 1989;33(2):285–92. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eide PK, Hole K. The role of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor subtypes and plasticity in the 5-HT systems in the regulation of nociceptive sensitivity. Cephalalgia. 1993;13(2):75–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1993.1302075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eriksson KS, Stevens DR, Haas HL. Serotonin excites tuberomammillary neurons by activation of Na(+)/Ca(2+)-exchange. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40(3):345–51. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng J, Cai X, Zhao J, Yan Z. Serotonin receptors modulate GABA(A) receptor channels through activation of anchored protein kinase C in prefrontal cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21(17):6502–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06502.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fields HL, Heinricher MM, Mason P. Neurotransmitters in nociceptive modulatory circuits. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:219–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fink K, Boing C, Gothert M. Presynaptic 5-HT autoreceptors modulate N-methyl-D-aspartate-evoked 5-hydroxytryptamine release in the guinea-pig brain cortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;300(1-2):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foehring RC, Lorenzon NM. Neuromodulation, development and synaptic plasticity. Can J Exp Psychol. 1999;53(1):45–61. doi: 10.1037/h0087299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Francis PT, Sims NR, Procter AW, Bowen DM. Cortical pyramidal neurone loss may cause glutamatergic hypoactivity and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: investigative and therapeutic perspectives. J Neurochem. 1993;60(5):1589–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fraser DD, MacVicar BA. Low-threshold transient calcium current in rat hippocampal lacunosum-moleculare interneurons: kinetics and modulation by neurotransmitters. J Neurosci. 1991;11(9):2812–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02812.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freund TF. GABAergic septal and serotonergic median raphe afferents preferentially innervate inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus. Epilepsy Res. 1992;7:79–91. Suppl. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freund TF, Gulyas AI, Acsady L, Gorcs T, Toth K. Serotonergic control of the hippocampus via local inhibitory interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(21):8501–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Funahashi M, Mitoh Y, Matsuo R. Activation of presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors facilitates glutamatergic synaptic inputs to area postrema neurons in rat brain slices. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2004;26(8):615–22. doi: 10.1358/mf.2004.26.8.863726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furst S. Transmitters involved in antinociception in the spinal cord. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48(2):129–41. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gandolfi O, Dall’Olio R, Roncada P, Montanaro N. NMDA antagonists interact with 5-HT-stimulated phosphatidylinositol metabolism and impair passive avoidance retention in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1990;113(3):304–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gandolfi O, Gaggi R, Voltattorni M, Dall’Olio R. The activation of serotonin receptors prevents glutamate-induced neurotoxicity and NMDA-stimulated cGMP accumulation in primary cortical cell cultures. Pharmacol Res. 2002;46(5):409–14. doi: 10.1016/s1043661802002050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gardette R, Krupa M, Crepel F. Differential effects of serotonin on the spontaneous discharge and on the excitatory amino acid-induced responses of deep cerebellar nuclei neurons in rat cerebellar slices. Neuroscience. 1987;23(2):491–500. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaspar P, Cases O, Maroteaux L. The developmental role of serotonin: news from mouse molecular genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(12):1002–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gavarini S, Becamel C, Chanrion B, Bockaert J, Marin P. Molecular and functional characterization of proteins interacting with the C-terminal domains of 5-HT2 receptors: emergence of 5-HT2 "receptosomes". Biol Cell. 2004;96(5):373–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glennon RA. Higher-end serotonin receptors: 5-HT(5), 5-HT(6), and 5-HT(7) J Med Chem. 2003;46(14):2795–812. doi: 10.1021/jm030030n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gras C, Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Pohl M, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. A third vesicular glutamate transporter expressed by cholinergic and serotoninergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22(13):5442–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05442.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Griffiths JL, Lovick TA. Co-localization of 5-HT 2A - receptor- and GABA-immunoreactivity in neurones in the periaqueductal grey matter of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2002;326(3):151–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guptarak J, Selvamani A, Uphouse L. GABAA-5-HT1A receptor interaction in the mediobasal hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2004;1027(1-2):144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Halliday G, Harding A, Paxinos G. Serotonin and Tachykinin Systems. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Academic Press; 1995. pp. 929–974. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hanley NR, Van de Kar LD. Serotonin and the neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic--pituitary-adrenal axis in health and disease. Vitam Horm. 2003;66:189–255. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(03)01006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harrison PJ. The hippocampus in schizophrenia: a review of the neuropathological evidence and its pathophysiological implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174(1):151–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harteneck C. Proteins modulating TRP channel function. Cell Calcium. 2003;33(5-6):303–10. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hasuo H, Matsuoka T, Akasu T. Activation of presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors facilitates excitatory synaptic transmission via protein kinase C in the dorsolateral septal nucleus. J Neurosci. 2002;22(17):7509–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07509.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Ionotropic glutamate receptor modulation of 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 mRNA expression in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(3):341–51. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heisler LK, Cowley MA, Kishi T, Tecott LH, Fan W, Low MJ, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Tatro JB, Zigman JM, Cone RD, Elmquist JK. Central serotonin and melanocortin pathways regulating energy homeostasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;994:169–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hicks TP, Krupa M, Crepel F. Selective effects of serotonin upon excitatory amino acid-induced depolarizations of Purkinje cells in cerebellar slices from young rats. Brain Res. 1989;492(1-2):371–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90922-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Higgins GA, Enderlin M, Haman M, Fletcher PJ. The 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100,907 attenuates motor and ’impulsive-type’ behaviours produced by NMDA receptor antagonism. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170(3):309–19. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holohean AM, Hackman JC. Mechanisms intrinsic to 5-HT2B receptor-induced potentiation of NMDA receptor responses in frog motoneurones. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143(3):351–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hori Y, Endo K, Takahashi T. Long-lasting synaptic facilitation induced by serotonin in superficial dorsal horn neurones of the rat spinal cord. J Physiol. 1996;492:867–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021352. Pt 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoyer D, Hannon JP, Martin GR. Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71(4):533–54. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hsiao CF, Wu N, Levine MS, Chandler SH. Development and serotonergic modulation of NMDA bursting in rat trigeminal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(3):1318–28. doi: 10.1152/jn.00469.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ito M, Oda Y. Electrophysiological evidence for formation of new corticorubral synapses associated with classical conditioning in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1994;99(2):277–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00239594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jackson DA, White SR. Receptor subtypes mediating facilitation by serotonin of excitability of spinal motoneurons. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29(9):787–97. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90151-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jacobs BL. Adult brain neurogenesis and depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16(5):602–9. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72(1):165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jacobs BL, Fornal CA. Serotonin and motor activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7(6):820–5. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jansen KL, Faull RL, Dragunow M, Synek BL. Alzheimer’s disease: changes in hippocampal N-methyl-D-aspartate, quisqualate, neurotensin, adenosine, benzodiazepine, serotonin and opioid receptors--an autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1990;39(3):613–27. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson MD. Synaptic glutamate release by postnatal rat serotonergic neurons in microculture. Neuron. 1994;12(2):433–42. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson SW, Mercuri NB, North RA. 5-hydroxytryptamine1B receptors block the GABAB synaptic potential in rat dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12(5):2000–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-02000.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kaneko T, Akiyama H, Nagatsu I, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical demonstration of glutaminase in catecholaminergic and serotoninergic neurons of rat brain. Brain Res. 1990;507(1):151–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90535-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Katsurabayashi S, Kubota H, Tokutomi N, Akaike N. A distinct distribution of functional presynaptic 5-HT receptor subtypes on GABAergic nerve terminals projecting to single hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44(8):1022–30. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawamata T, Omote K, Toriyabe M, Yamamoto H, Namiki A. The activation of 5-HT(3) receptors evokes GABA release in the spinal cord. Brain Res. 2003;978(1-2):250–5. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02952-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kerenyi L, Ricaurte GA, Schretlen DJ, McCann U, Varga J, Mathews WB, Ravert HT, Dannals RF, Hilton J, Wong DF, Szabo Z. Positron emission tomography of striatal serotonin transporters in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(9):1223–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.9.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kew JN, Kemp JA. Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor structure and pharmacology. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179(1) doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2200-z. 4-29 Epub 2005 Feb 25. Review Erratum in (2005) Psychopharmacology (Berl.)182(2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khanna JM, Kalant H, Chau A, Shah G, Morato GS. Interaction between N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and serotonin (5-HT) on ethanol tolerance. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35(1):31–5. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kishimoto K, Koyama S, Akaike N. Synergistic mu-opioid and 5-HT1A presynaptic inhibition of GABA release in rat periaqueductal gray neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(5):529–38. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koyama S, Matsumoto N, Murakami N, Kubo C, Nabekura J, Akaike N. Role of presynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT3 receptors in modulation of synaptic GABA transmission in dissociated rat basolateral amygdala neurons. Life Sci. 2002;72(4-5):375–87. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kulla A, Manahan-Vaughan D. Modulation by serotonin 5-HT(4) receptors of long-term potentiation and depotentiation in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12(2):150–62. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lai YY, Kodama T, Siegel JM. Changes in monoamine release in the ventral horn and hypoglossal nucleus linked to pontine inhibition of muscle tone: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurosci. 2001;21(18):7384–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07384.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laine J, Axelrad H. Extending the cerebellar Lugaro cell class. Neuroscience. 2002;115(2):363–74. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Landy S, Rice K, Lobo B. Central sensitisation and cutaneous allodynia in migraine: implications for treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(6):337–42. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee K, Dixon AK, Pinnock RD. Serotonin depolarizes hippocampal interneurones in the rat stratum oriens by interaction with 5-HT2 receptors. Neurosci Lett. 1999;270(1):56–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee M, Strahlendorf JC, Strahlendorf HK. Modulatory action of serotonin on glutamate-induced excitation of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Brain Res. 1985;361(1-2):107–13. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li H, Lang B, Kang JF, Li YQ. Serotonin potentiates the response of neurons of the superficial laminae of the rat spinal dorsal horn to gamma-aminobutyric acid. Brain Res Bull. 2000;52(6):559–65. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li P, Kerchner GA, Sala C, Wei F, Huettner JE, Sheng M, Zhuo M. AMPA receptor-PDZ interactions in facilitation of spinal sensory synapses. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(11):972–7. doi: 10.1038/14771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li P, Zhuo M. Silent glutamatergic synapses and nociception in mammalian spinal cord. Nature. 1998;393(6686):695–8. doi: 10.1038/31496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li Volsi G, Licata F, Fretto G, Di Mauro M, Santangelo F. Influence of serotonin on the glutamate-induced excitations of secondary vestibular neurons in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;172(2):446–59. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Licata F, Li Volsi G, Ciranna L, Maugeri G, Santangelo F. 5-Hydroxytryptamine modifies neuronal responses to glutamate in the red nucleus of the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1998;118(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s002210050255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Licata F, Li Volsi G, Di Mauro M, Fretto G, Ciranna L, Santangelo F. Serotonin modifies the neuronal inhibitory responses to gamma-aminobutyric acid in the red nucleus: a microiontophoretic study in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;167(1):95–107. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Licata F, Li Volsi G, Maugeri G, Ciranna L, Santangelo F. Effects of glutamate on the serotonin-induced responses of vestibular neurons. Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper. 1990;66(8):779–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lopez-Garcia JA. Serotonergic modulation of the responses to excitatory amino acids of rat dorsal horn neurons in vitro: implications for somatosensory transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(4):1341–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ma QP. Co-localization of 5-HT(1B/1D/1F) receptors and glutamate in trigeminal ganglia in rats. Neuroreport. 2001;12(8):1589–91. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200106130-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Malleret G, Hen R, Guillou JL, Segu L, Buhot MC. 5-HT1B receptor knock-out mice exhibit increased exploratory activity and enhanced spatial memory performance in the Morris water maze. J Neurosci. 1999;19(14):6157–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06157.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):541–7. doi: 10.1038/87865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Marchetti E, Chaillan FA, Dumuis A, Bockaert J, Soumireu-Mourat B, Roman FS. Modulation of memory processes and cellular excitability in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats by a 5-HT4 receptors partial agonist, and an antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(7):1021–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK. Excitation of interneurons in piriform cortex by 5-hydroxytryptamine: blockade by MDL 100,907, a highly selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;259(2):137–41. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Martin KF, Hannon S, Phillips I, Heal DJ. Opposing roles for 5-HT1B and 5-HT3 receptors in the control of 5-HT release in rat hippocampus in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106(1):139–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matsuoka T, Hasuo H, Akasu T. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 1B receptors mediate presynaptic inhibition of monosynaptic IPSC in the rat dorsolateral septal nucleus. Neurosci Res. 2004;48(3):229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Maura G, Carbone R, Guido M, Pestarino M, Raiteri M. 5-HT2 presynaptic receptors mediate inhibition of glutamate release from cerebellar mossy fibre terminals. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;202(2):185–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90293-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McCall RB, Aghajanian GK. Serotonergic facilitation of facial motoneuron excitation. Brain Res. 1979;169(1):11–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.McCleane GJ, Suzuki R, Dickenson AH. Does a single intravenous injection of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron have an analgesic effect in neuropathic pain? A double-blinded, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1474–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000085640.69855.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McMahon LL, Kauer JA. Hippocampal interneurons are excited via serotonin-gated ion channels. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78(5):2493–502. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Meguid MM, Fetissov SO, Varma M, Sato T, Zhang L, Laviano A, Rossi-Fanelli F. Hypothalamic dopamine and serotonin in the regulation of food intake. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):843–57. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Melik-Musyan AB, Fanardzhyan VV. Morphological characteristics of Lugaro cells in the cerebellar cortex. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2004;34(6):633–8. doi: 10.1023/b:neab.0000028297.30474.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Meneses A. Involvement of 5-HT(2A/2B/2C) receptors on memory formation: simple agonism, antagonism, or inverse agonism? Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22(5-6):675–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1021800822997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66(6):355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Millhorn DE, Hokfelt T, Seroogy K, Oertel W, Verhofstad AA, Wu JY. Immunohistochemical evidence for colocalization of gamma-aminobutyric acid and serotonin in neurons of the ventral medulla oblongata projecting to the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1987;410(1):179–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(87)80043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Millhorn DE, Hokfelt T, Seroogy K, Verhofstad AA. Extent of colocalization of serotonin and GABA in neurons of the ventral medulla oblongata in rat. Brain Res. 1988;461(1):169–74. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]