Abstract

The trafficking of ionotropic glutamate (AMPA, NMDA and kainate) and GABAA receptors in and out of, or laterally along, the postsynaptic membrane has recently emerged as an important mechanism in the regulation of synaptic function, both under physiological and pathological conditions, such as information processing, learning and memory formation, neuronal development, and neurodegenerative diseases. Non-ionotropic glutamate receptors, primarily group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), co-exist with the postsynaptic ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors. The ability of mGluRs to regulate postsynaptic phosphorylation and Ca2+ concentration, as well as their interactions with postsynaptic scaffolding/signaling proteins, makes them well suited to influence the trafficking of ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors. Recent studies have provided insights into how mGluRs may impose such an influence at central synapses, and thus how they may affect synaptic signaling and the maintenance of long-term synaptic plasticity. In this review we will discuss some of the recent progress in this area: i) long-term synaptic plasticity and the involvement of mGluRs; ii) ionotropic glutamate receptor trafficking and long-term synaptic plasticity; iii) the involvement of postsynaptic group I mGluRs in regulating ionotropic glutamate receptor trafficking; iv) involvement of postsynaptic group I mGluRs in regulating GABAA receptor trafficking; v) and the trafficking of postsynaptic group I mGluRs themselves.

Key Words: Metabotropic, ionotropic, glutamate receptor, GABAA receptor, receptor trafficking, endocytosis, hippocampus, synaptic plasticity

1. INTRODUCTION

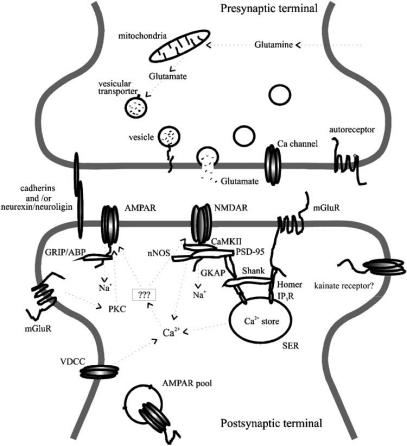

Synaptic transmission between neurons in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) is constantly modified in activity-dependent or independent ways. This plasticity of central synapses has considerable implications for brain function. It is generally believed that such plasticity, especially the long-lasting activity-dependent ones, underlies learning and memory processes and the developmental maturation of neural circuitry, as well as is involved in pathological conditions and neurodegenerative diseases [2, 12, 74]. Most excitatory central synapses use glutamate as neurotransmitter to activate primarily postsynaptically located ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors. The ionotropic glutamate receptors include AMPA receptors (AMPARs), NMDA receptors (NMDARs) and kainate receptors, and mediate (mostly) fast excitatory synaptic transmission. The metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), a class of G-protein coupled receptors, do not directly mediate fast synaptic transmission but have an essential role in regulating many cellular functions, including synaptic transmission (Fig. 1). At inhibitory synapses, fast synaptic inhibition is primarily mediated through the activation of postsynaptic ionotropic GABAA receptors by the neurotransmitter GABA [2].

Fig. (1).

Schematic structure and function of a hippocampal CA1 glutamatergic synapse. Postsynaptic AMPARs, NMDARs and kainate receptors are depicted as tetrameric complexes. AMPARs are linked to scaffolding proteins GRIP/ABP. NMDARs are associated with scaffolding and signaling proteins such as PSD-95, CaMKII, nNOS and GKAP. Kainate receptors are depicted alone for simplification. The mGluRs are illustrated as proteins with seven transmembrane segments. They are linked to a scaffolding protein Homer which in turn can mediate an interaction between mGluRs and NMDARs via Shank protein as well as mediate an interaction between mGluRs and intracellular Ca2+ stores via rP3Rs. Cell adhesion molecules such as cadherins and neurexin/neuroligin link the presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes. Glutamate released from presynaptic vesicles by exocytosis mainly binds to postsynaptic AMPARs, NMDARs or kamate receptors which open channels, allowing various ions to pass. A rise in Ca2+ in the postsynaptic terminal can trigger intracellular signaling cascades which can alter the efficacy of synaptic transmission. The ion passage through the receptor channels results in synaptic currents and potentials which can be detected and recorded using electrophysiology techniques. Meanwhile, the released glutamate binds also to postsynaptic and presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors which results in changes in the protein kinase C (PKC) activity, Ca2+ release from intracellular stores or cAMP levels. A representative intracellular pool of AMPARs is also shown.

The hippocampus is a CNS structure which is not only crucial for information processing and learning and memory formation, but is also prone to diseases such as Alzheimer and epilepsy. The ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors and GABAA receptors mediate much of the synaptic transmission in the hippocampus and are indispensable for its physiological function and for the development of its pathology. Therefore, the synaptic transmission mediated via glutamate and GABAA receptors has been the subject of extensive studies. Recent studies have indicated that trafficking of ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors in and out of, or laterally along, the postsynaptic membrane of hippocampal neurons is an important mechanism underlying synaptic plasticity [16, 19, 23, 72]. Important progress has been made in revealing how this trafficking of ionotropic receptors is regulated, and an involvement of postsynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors, specifically groups I mGluRs, in this trafficking has been suggested [60, 107, 125]. The mGluRs affect synaptic function and plasticity via their diverse actions on neurons/synapses, and in the present review the overall influence of mGluR activation on synaptic plasticity will be briefly described. However, the main focus will be the recent progress concerning the role of group I mGluRs in glutamate and GABAA receptor trafficking, and thereby in the long-term synaptic plasticity. The review will be based largely on studies on hippocampal synapses, but when found relevant, will include data from other central synapses or cells.

2. MGLURS AND LONG-TERM SYNAPTIC PLASTICITY AT CENTRAL SYNAPSES

2.1. mGluRs at Central Synapses

The mGluRs differ from ionotropic glutamate receptors in that they are coupled to and exert their effects via G-proteins. The mGluRs are divided into three groups based on the homology of their amino acid sequences. The group I includes mGluR1 and mGluR5, group II includes mGluRs2-3, and group III includes mGluR4 and mGluRs6-8. Activation of group I mGluRs causes phosphoinositide hydrolysis by phospholipase C (PLC), resulting in protein kinase C (PKC) activation via diacylglycerol (DAG) and Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular Ca2+ stores via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). On the other hand, activation of group II and III mGluRs results in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and reduced levels of cAMP. These actions in turn have diverse cellular effects, such as modulation of intrinsic postsynaptic excitability (e.g. via voltage-dependent K+ channels), of presynaptic neurotransmitter release (e.g. via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels) or direct modulation of postsynaptic ionotropic receptors [4, 24, 25, 109]. In the CNS, group I mGluRs are primarily located at the postsynaptic side, whereas group II and III mGluRs are primarily located at the presynaptic membrane. Since mGluRs often co-localize with the ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors at the same synapses, their roles in regulating the synaptic functioning of ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors have been much studied. Even though the main focus of this review will be the role of group I mGluRs in glutamate and GABAA receptor trafficking in long-term synaptic plasticity, we will first introduce some basic facts concerning synaptic transmission and plasticity, and effects thereupon by mGluR activation.

2.2. Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity Induction

At excitatory central synapses, certain types of stimulation, e.g. a repetitive stimulation, can lead to long-lasting changes in synaptic strength, preferentially related to AMPAR-mediated synaptic signaling [12]. These changes manifest themselves as alterations in the total amount of passage of ions through the ionotropic glutamate receptors, which can be detected and recorded using electrophysiological techniques. The changes are normally seen as long-lasting (on a time scale of hours to weeks/months) increase or decrease in excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) or potentials (EPSPs). Long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) are two prominent forms of such synaptic plasticity, and are seen as the cellular basis for learning and memory formation and for neural development [12, 73, 74]. At inhibitory synapses such long lasting changes in synaptic strength, expressed as an increase or decrease in the inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) or potentials (IPSPs), can modulate the excitability of excitatory neurons, cause neuronal oscillation and synchronization, and regulate the synaptic plasticity at excitatory synapses [36]. There are, in the hippocampus and other brain areas, different forms of LTP and LTD, generally subdivided into NMDAR-dependent, or -independent, after whether their induction depends critically on the activation of NMDARs or not. In the case of NMDAR-dependent LTP/LTD, their induction mechanisms are relatively well defined. It is commonly agreed that their induction requires postsynaptic NMDAR channel opening and Ca2+ influx through these channels, this influx giving rise to LTP or LTD depending on the temporal and spatial characteristics of the Ca2+ rise in the postsynaptic compartment [131]. It has also been suggested that NMDARs with different subunit composition (subtype NR2A versus NR2B) or synaptic locations (synaptic versus extrasynaptic) by coupling to distinct intracellular signaling machineries should be critical for determining whether LTP or LTD is induced [66, 79]. However, this notion has not been consistent with earlier experiments carried out in genetically modified mice [57, 58, 111, 121], and has been questioned by a recent study showing that both NR2A and NR2B subtypes of NMDARs are capable of inducing LTP, and possibly also LTD [10]. In the case of NMDAR-independent LTP/LTD, their induction mechanisms are less clear, but may also involve synaptic Ca2+ rise which can be achieved by Ca2 influx through other channels, e.g. via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, or/and by Ca2+ release from intracellular stores [12, 74, 110, 112]. This can also occur presynaptically, such as for LTP at the hippocampal mossy fiber-CA3 pyramidal neuron synapse [73, 89] (but see Yeckel et al. [127] and Henze et al. [41]). There have been a considerable number of studies investigating how different factors may influence the induction of both NMDAR-dependent and -independent long-term synaptic plasticity, and mGluRs have been shown to play an important role under certain conditions.

2.3. mGluRs Involvement in Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity Induction

Various studies have shown that mGluRs are either necessary, or dispensable, or irrelevant, for the induction of different forms of long-term synaptic plasticity. There are many reasons that can account for such discrepancies, including different forms of synaptic plasticity studied, different experimental conditions/parameters, different developmental stages of glutamate/GABAA receptors, specific agonists/antagonists used, and the timing of mGluR activation etc. [4, 13, 81]. Nonetheless, mGluR activation has been found to modulate the induction of NMDAR-dependent long-term synaptic plasticity. For example, in the hippo-campal CA1 area the broad spectrum mGluR agonist 3R-dicarboxylic acid (ACPD) was found to facilitate, or prime, the subsequent induction of LTP induced by high frequency stimulation, an effect involving group I mGluRs since it was antagonized by the group I mGluR antagonist L-2-amino-3-phosphonopropionic acid [21], as well as was induced by the specific group I mGluR agonist 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) [22]. By using the selective mGluR1 antagonist +/-2-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (LY367385) and the selective mGluR5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), mGluR5 has been found to be involved in the induction of the late (protein synthesis-dependent) phase of NMDAR-dependent LTP induced by strong stimulation, while both mGluR1 and mGluR5 were involved in the induction of LTP obtained using weak stimulation [34]. A blockade of group I mGluRs, specifically mGluR5, has also been shown to impair LTP induced by high frequency stimulation as well as the spatial learning in animals in vivo [86, 87]. All these effects were observed at concentrations (of mGluR agonists or antagonists) which did not affect basal synaptic transmission [21, 30, 34]. Neither did the priming effect depend on altered NMDA signaling since e.g., a blockade of the DHPG-induced potentiation of NMDA responses by mGluR5 antagonist LY344545 failed to affect the priming effect [30]. These observations raise the possibility that group I mGluRs may affect plasticity induction via e.g. influencing certain phases of receptor trafficking so that receptors are more easily available when the plasticity induction is applied. The genetic approach has also been used for studying the involvement of mGluR subtypes in synaptic plasticity induction [53]. For example, mice lacking mGluR5 showed impaired learning and reduced CA1 NMDAR-dependent LTP [69]. The mGluR1- and mGluR5-knockout mice have also been demonstrated to have reduced corticostriatal LTP [39].

Besides the fact that, as discussed above, group I mGluR activation can affect the induction properties, such as the threshold, of the NMDAR-dependent long-term synaptic plasticity, group I mGluR activation can under certain conditions also induce synaptic plasticity. This plasticity is also primarily expressed as a long-lasting change of AMPAR-mediated synaptic signaling and does not require NMDAR activation for its induction. For example, synaptic activation by low frequency stimulation (1-2 Hz) for several minutes under the blockade of NMDARs resulted in a form of LTD which is solely dependent on activation of mGluRs [102] or more specifically group I mGluRs [107], indicating that synaptically released glutamate is sufficient to activate the group I mGluRs to induce synaptic plasticity. Application of exogenous mGluR agonists, especially group I agonists alone, or in combination of synaptic activation, has also been used to study the role of mGluR activation in synaptic plasticity. For example, in hippocampal slices, ACPD application together with a synaptic activation resulted in LTP while ACPD application alone resulted instead in LTD. Thus mGluRs may co-activate with NMDARs to induce LTP but induce LTD alone via its action on IP3 receptors [35]. In hippocampal slices, DHPG (group I mGluR agonist) application for a few minutes resulted in LTD [102, 107, 125, 129] which was dependent on dendritic protein synthesis [107]. Application of DHPG was also found to depotentiate a previously established LTP and this depotentiation was mediated primarily by mGluR5 and depended also on protein synthesis [129]. In the hippocampus in vivo, DHPG was found to induce a slow-onset LTP which correlated with increased expression levels of certain proteins and immediate early genes, and which may contribute to late phases of synaptic plasticity [14]. This slow-onset LTP was associated with an up-regulation of mGluR5 (and down-regulation of mGluR2/3), as seen by using Western blot or in situ hybridization [77]. Notably, in hippocampal slices, activation of group I mGluRs by a prior preconditioning stimulation can produce a PKC-dependent inactivation of these mGluRs, which in turn inhibits the induction of group I mGluR-induced LTD/depotentiation, resulting in a form of metaplasticity [122].

3. IONOTROPIC GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR TRAFFICKING AS AN IMPORTANT MECHANISM FOR LONG-TERM SYNAPTIC PLASTICITY EXPRESSION

The induction of long-term synaptic plasticity has overall been relatively well defined, and, as discussed above, group I mGluRs have been found to play a role in this induction. However, how the synaptic modifications (normally a persistent up- or down-regulation of AMPAR-mediated synaptic signaling) are sustained during the course of hours to weeks/months is much less understood. Recently, it has been increasingly realized that membrane receptor trafficking is an important mechanism by which neurons can rapidly modify their responses to external/internal stimuli. The membrane trafficking of ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors has thus emerged as an important mechanism for long-lasting synaptic plasticity [16, 23]. Before discussing the possible role of group I mGluRs in it, we will briefly introduce the synaptic trafficking of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the context of long-term synaptic plasticity.

3.1. AMPAR Trafficking

New evidence suggests that AMPARs are constitutively cycling in and out of the synapse, or laterally along the synaptic membrane, on a rapid time scale (seconds to minutes), and that a change in such trafficking is an important mechanism for expressing and sustaining long-lasting synaptic plasticity [16, 76]. In hippocampal slices, LTP was demonstrated to be associated with exocytosis of postsynaptic AMPARs [67], and in cultured neurons, NMDAR activation was shown to induce membrane insertion of new AMPARs and LTP [68]. For the endocytosis of AMPARs, the clathrin-mediated endocytosis pathways are involved, and redistribution of synaptic AMPARs can be regulated by neuronal activity [75]. NMDAR activation can trigger AMPAR endocytosis via activation of the calcium-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin [7]. Another form of receptor trafficking involves a lateral movement of AMPARs at the postsynaptic membrane on a very fast time scale (seconds) [19], and theoretical work predicts that such lateral movement can significantly regulate synaptic strength [101]. Endocytosis of synaptic AMPARs may in fact follow a two-step model in which receptors first diffuse laterally to extrasynaptic sites before they are subsequently internalized [96, 130]. One protein that has convincingly been shown to regulate AMPAR trafficking is stargazin, a membrane AMPAR interacting protein [18] which, in addition, can regulate AMPAR gating [95, 113]. Recently, AMPAR-mediated signaling was shown to be quickly silenced on a fast time scale (seconds) at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses in the developing hippocampus, presumably via removal of postsynaptic AMPARs [124]. This result indicates that a very low level of synaptic activity can result in a rapid change in AMPAR trafficking, at least at developing central synapses.

3.2. NMDAR Trafficking

Recent studies indicate that NMDARs are also very mobile, both capable of cycling in and out of postsynaptic membranes [5, 38, 94, 98] and of moving laterally between synaptic and extrasynaptic pools [115]. A study of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention of NMDAR subunits and of their transportation from ER to the plasma membrane showed that activity-dependent mRNA splicing can control the export from ER and the synaptic delivery of NMDARs [82]. However, how the synaptic trafficking of NMDARs is regulated under physiological and pathological situations remains less clear [120]. PKC can induce a rapid delivery of functional NMDARs and an increase in NMDAR clusters on the surface of dendrites and dendritic spines, and activation of mGluRs can enhance such an NMDAR delivery to the postsynaptic membrane [60]. However, in another study, using cultured rat hippocampal neurons, the opposite effect was found in that a selective activation of PKC with phorbol esters induced a rapid dispersal of NMDARs from synaptic to extrasynaptic plasma membrane [32]. By using single-molecule tracking in hippocampal neurons, it was demonstrated that, like AMPARs, NMDARs displayed a high degree of lateral mobility at synapses. This NMDAR trafficking was shown to be regulated by PKC activation but not by neuronal activity [37].

3.3. Kainate Receptor Trafficking

Kainate receptors contribute to excitatory postsynaptic currents in many CNS regions including the hippocampus. They can play both post- and presynaptic roles, and be involved in short- and long-term synaptic plasticity as well as in pathological conditions [48]. A change in the trafficking of kainate receptors would alter their regulatory functions [28, 50, 51]. Indeed, it has been found that kainate receptor subunits GluRs5-6 interact with postsynaptic PDZ domain-containing proteins at mossy fiber-CA3 synapses [46], making kainate receptors possible targets for trafficking. Nevertheless, kainate receptor trafficking seems to employ mechanisms distinct from those of the AMPARs [18] and multiple trafficking signals are involved in the trafficking of kainate receptors subtypes, e.g. GluRs5-6 and KA2 [97, 126]. Different splice variant isoforms of GluR5 and GluR6 (GluR5a-c, GluR6a-b) have different surface expression at the neuronal membrane. For example, GluR6a is rich at the membrane while GluR6b, GluR5a-c are rich in ER, suggesting that the splice variants and subunit composition of kainate receptors will affect their trafficking from the ER to the plasma membrane [52].

4. GROUP I MGLURS REGULATE IONOTROPIC GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR TRAFFICKING

4.1. Interaction Between Group I mGluRs and Scaffolding/Receptor Proteins

Group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and mGluR5) are believed to exist primarily postsynaptically at hippocampal synapses and to be linked to postsynaptic PSD-95 via two scaffolding proteins Homer and Shank [42, 105]. Shank, as well as GKAP/SAPAP (a family of proteins highly concentrated in the PSD and bound to the guanylate kinase domain of PSD-95), cross-link the mGluR1/5/Homer complex with the NMDAR/PSD-95 complex, and therefore plays a role in the signaling mechanisms of both mGluRs and NMDARs [88, 116].Both mGluR1 and mGluR5 undergo alternative splicing to generate isoforms, such as mGluR1a-d, and mGluR5a-b, differing in their C-terminal sequence, which may be differentially regulated. The Homer/Vesl proteins have been increasingly indicated as major regulating proteins for group I mGluRs [31, 123]. A PSD-95/PDZ domain-containing protein termed tamalin was shown to interact with group I mGluRs, especially mGluR1a and mGluR5, via its PDZ domain-containing terminal [55]. At the same time, PSD-95 family members also interact with NMDAR and AMPAR subunits (NR2 and GluR1). Postsynaptic mGluR5 and mGluR1 are thereby well positioned such that their activation can influence NMDAR and AMPAR functions. It has been suggested that there is a reciprocal positive feedback interaction between mGluR5 and NMDARs [1].

4.2. Group I mGluRs Regulate Glutamate Receptor Trafficking at Central Synapses

As described above, hippocampal CA3-CA1 excitatory synapses display a form of LTD which is dependent on group I mGluR activation [102, 107, 125]. This activation has been found to lead to an internalization of AMPARs/ NMDARs and a loss of receptors from the surface membrane of synapses [107, 125]. This result indicates that group I mGluRs have the ability to regulate the trafficking of AMPARs and NMDARs at hippocampal synapses. In a further study, activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) was shown to be involved in the induction of this LTD. A potential downstream process of the p38 MAPK activation is the formation of the guanyl nucleotide dissociation inhibitor-Rab5 complex leading to an accelerating AMPAR endocytosis [47]. The DHPG (group I mGluR agonist) indueed-depotentiation of previously established LTP was found to be associated with a reduced increase of the surface expression of AMPARs seen with LTP, suggesting that activation of mGluR5 triggers a protein synthesis-dependent internalization of synaptic AMPARs [129]. AnmGluR-dependent LTD based on an internalization of AMPARs has also been indicated in other structures than hippocampus. For example, in nucleus accumbens (NAc) neurons, glutamate-induced AMPAR internalization was affected by the group I mGluR agonist DHPG and antagonist PHCCC [78]. In neostriatal neurons, activation of group I mGluRs by DHPG can regulate the activity of casein kinase 1 (CK1) which has been implicated in a variety of cellular functions, including intracellular trafficking [63]. DHPG activates CK1 via Ca2+-dependent stimulation of calcineurin followed by a subsequent dephosphorylation process [65] which resembles the process of DHPG-induced AMPAR endocytosis. At the same time, activation of mGluR1 accelerates NMDAR insertion into the membrane [60]. The mGluR5 is also subjected to endogenous phosphorylation and dephosphorylation which can be influenced by NMDAR activation. This suggests that endogenous phosphorylation regulatory mechanisms can be used to mediate crosstalk between synaptic ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors [92]. It has been previously shown that ionotropic (GABAA) and metabotropic (dopamine D5) receptors can have direct physical interaction in hippocampal neurons [64]. It will be interesting to see whether there can be direct protein-protein interaction between group I mGluRs and ionotropic glutamate receptors, and how this would influence the trafficking of the latter in the hippocampal neurons. However, the recently described AMPAR silencing (and trafficking) in the developing hippocampus appears not to be regulated by mGluR activation [124]. This would imply that there might be multiple mechanisms or pathways for the trafficking of ionotropic glutamate receptors. From a study using a fluorescent marker to monitor presynaptic activity during mGluR-induced LTD at hippocampal CA3-CA1 excitatory synapses, it was suggested that the LTD can be explained by an altered presynaptic transmitter release, even though the group I mGluRs are activated postsynaptically [128].Morphological changes in terms of synapse elimination was also reported for this LTD [106]. However, a presynaptic expression for mGluR-induced synaptic plasticity may be limited to the neonatal period, there being a developmental switch from presynaptic to postsynaptic expression with age [90].

4.3. Molecular Mechanisms for Group I mGluRs in Regulation of Receptor Trafficking

The molecular mechanisms for receptor (especially AMPAR) trafficking have been extensively investigated. Numerous studies have identified several receptor interacting proteins and shown that they play important roles in the receptor trafficking and clustering at the synaptic membrane [23, 76]. These are proteins that either contain, or do not contain, PDZ domains, a protein-protein interaction motif. The glutamate receptor interacting proteins/AMPAR binding protein (GRIP/ABP), protein interacting with C-kinase (PICK1), and synapse associated protein 97 (SAP97) are examples of PDZ containing proteins. The N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein (NSF), soluble NSF attachment proteins (α, β-SNAP), Lyn (a Src-family non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase), the guanine nucleotide binding protein (Gαi1) and stargazin are examples of proteins which do not contain PDZ domains [15, 16, 28, 40, 54, 105].

There are several possible ways for mGluRs to intervene in the trafficking of ionotropic receptors to the synaptic membrane. First, the activation of group I mGluRs can, via IP3, result in Ca2+ concentration changes in the postsynaptic compartment, thus possibly regulating the receptor interacting proteins mentioned above. Endocytosis of AMPARs may involve the Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin [7, 62]. The NR2B subunit of the NMDAR can also be modulated by Ca2+ via Ca2+-dependent CaMKII [6]. Thus, group I mGluRs are likely to take part in the regulation of receptor trafficking through Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. Second, activation of PKC, via DAG, can also regulate certain receptor interacting proteins, e.g., disrupting the interaction between PICK1 and intracellular AMPAR clusters resulting in a rapid translocation of AMPARs to the membrane surface. PKC can also induce a rapid delivery of functional NMDARs to the synaptic surface membrane [59, 60]. Thus, the activation of group I mGluRs can modulate AMPAR and NMDAR trafficking also through PKC activation. Finally, tyrosine kinases have been indicated to interact with GRIP and PICK1 [15]. GRIP/ABP have also been shown to interact with Ephrin receptors and their ligands which activate also Src tyrosine kinase [17, 114]. At the mossy fiber-CA3 synapse, synaptic activation of mGluR1 can lead to G-protein-independent activation of a Src-family tyrosine kinase [44, 45].

For kainate receptors, scaffolding proteins that contain PDZ domains, such as PSD-95, SAP97, PICK1 and GRIP were shown to interact largely with GluR6a, and to less extent with other subtypes. The PKC-dependent phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of GluR6 can stabilize its binding with GRIP, thus indicating that group I mGluR can regulate kainate receptor trafficking and clustering through regulating PKC activity in the synapse [51]. Kainate receptors have also been shown to interact with cadherin/ catenin [26], implying that group I mGluR may also intervene in kainate receptor function/trafficking by regulating the Ca2+-dependent intercellular adhesion molecules cadherin/catenin.

Interestingly, group I mGluR activation can lead to both LTP and LTD which both have been shown to involve receptor trafficking in their expression. As discussed above, group I mGluR activation may regulate receptor trafficking via different signaling pathways, therefore it is possible that different stimulation protocols such as those used for inducing LTP and LTD, respectively, may engage those pathways differentially, contributing to either LTP or LTD. For example, the high frequency stimulation used to induce LTP was suggested to activate PKC pathways while DHPG induces LTD via activation of the p38 MAPK pathway [100]. Besides, group I mGluR activation may only be required for certain aspects of LTP induction, e.g. to lower the induction threshold while LTD may require group I mGluR activation to trigger induction as well as to maintain the receptor trafficking during its expression. Finally, group I mGluR activation by LTD-inducing stimulation triggers protein synthesis process that is required for the receptor trafficking [107] while there is so far no evidence that receptor trafficking during LTP requires protein synthesis.

5. GABAA RECEPTOR TRAFFICKING AND GROUP I MGLURS

Each GABAA receptor consists of several subunits in a heteromeric complex. There are multiple GABAA receptor subtypes (predominantly composed of α, β and γ subunits) differentially expressed in distinct neuronal populations [103]. The inhibitory activity mediated by ionotropic GABAA receptors normally imposes an effective constraint on hippocampal activity, a structure known to be prone to CNS pathology such as epilepsy. An altered GABA transmission by changed GABAA receptor trafficking can thus have a profound effect on normal synaptic transmission, as well as situations associated with epileptogenesis. In fact, GABA transmission can be both up- and down-regulated in a long-term manner [70, 91]. Similar to the ionotropic glutamate receptors, a change in GABAA receptor number on the postsynaptic membrane is an efficient means of regulating GABAA signaling [56, 72, 91, 117, 119]. The surface number and subunit stability of GABAA receptors is regulated by the ubiquitin-like protein Plic-1 which blocks the degradation of ubiquitinated receptors and enhance the insertion of GABAA receptors into the membrane [9]. PKB(also called Akt) can phosphorylate GABAA receptors both in vitro and in vivo, and increase the surface number of receptors [119]. A 17 kDa GABAA receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) was identified to interact with the GABAA γ2 subunit, microtubules, and NSF which is involved in receptor endocytosis. GABARAP can affect GABAA receptor trafficking in cultured hippocampal neurons [61]. By using antibody tagging in rat hippocampal neurons in culture, internalized GABAA receptors were found mainly at postsynaptic sites where the GABAA receptor anchoring protein gephyrin interacts with cytoplasmic proteins [118]. It has also been shown that GABAA receptor trafficking can be regulated by the same glial-generated protein as for AMPA receptor trafficking, but with the opposite effect. Thus, in hippocampal pyramidal cells tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFalpha) causes a rapid exocytosis of AMPARs but endocytosis of GABAA receptors [8, 108]. Similar to ionotropic glutamate receptors, the trafficking of GABAA receptors may also be regulated through PKC, or calcineurin, pathways through the activation of group I mGluRs [56, 72]. Indeed, activation of PKC modulates GABAA receptor internalization via a β2 subunit motif, in both cerebral cortical neuronal slices and cultures [43]. Functionally, group I mGluRs were suggested to contribute to the sustained potentiation of GABAA synaptic transmission in pyramidal cells induced by theta burst stimulation [93].

6. TRAFFICKING OF GROUP I MGLURS AT POSTSYNAPTIC MEMBRANE

In recent years, the trafficking of mGluRs themselves has also received substantial attention. In non-neuronal systems mGluRs can be transported to and from the surface of cells in response to external stimuli. For example, by using combined imaging of Ca2+ and GFP fluorescence in single human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells to simultaneously monitor the movement and function of mGluR1a, it was shown that the surface expression of mGluR1, like that of ionotropic glutamate receptors, can be rapidly regulated in response to agonist activation [29]. The trafficking of group I mGluRs was found to be regulated by Homer-lb and -lc. Whereas Homer-lb inhibits the surface expression of mGluRs [99] Homer-lc induces clustering of mGluR1a in the plasma membrane [20]. Agonist-induced internalization of mGluR1a is arrestin- and dynamin-dependent [83] and is subjected to PKC, CaMKII and PKA regulation [84, 85]. It was also shown in the same cell system that the agonist-dependent mGluR1a internalization is β-arrestin dependent while the agonist-independent internalization involves the β-arrestin-independent targeting of mGluR1a to clathrin-coated vesicles [27]. When the C6 glioma cells were treated with L-glutamate, quisqualate or ACPD, cell surface mGluRs were down-regulated through clathrin-mediated endocytosis [71].

In neuronal systems, the cell surface expression of mGluR5 in cultured cerebellar granule cells depends on Homer-1 protein [3]. Depolarized Purkinje cells can increase their cell surface mGluR1 by blocking their internalization through MAPK activity and Homer-la expression [80]. The Homer/Vesl proteins have been implicated in the regulation of group I mGluR trafficking in neurons [31, 123]. For example, Homer- lc was found to reduce the rate of loss of mGluR1a from the cell surface and to increase the extent of dendritic trafficking of the receptor in rat primary cultured neurons [20]. In primary hippocampal neurons in culture mGluR5 is endocytosed by a clathrin-independent pathway [33]. Using single particle tracking to follow mGluR5 movement in real time, mGluR5 was found to be transported actively on the cell surface through actin-mediated retrograde transport of microtubules [104]. The intracellular signaling system in the mGluR endocytosis seems to involve the small GTP-binding protein Ral, its guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and phospholipase D2 which are constitutively associated with mGluR1 and regulate constitutive mGluR1 endocytosis in both HEK cells and neurons [11]. The agonist-stimulated differential sorting of the mGluR1 receptor and β-arrestin, as well as the activation of MAP kinases by mGluR1 agonist, were demonstrated in cultured cerebellar Purkinje cells [49]. Tamalin, a PSD-95/PDZ domain-containing protein, plays a key role in the association of group I mGluRs with members of small GTP-binding proteins and their related proteins. This association contributes to the trafficking and localization of group I mGluRs at hippocampal cell culture synapses [55]. Therefore, mGluR1 and mGluR5 are constitutively or activity-dependently internalized in heterologous cell cultures, neuronal cultures, and intact neuronal tissues. Similar to ionotropic glutamate receptors [23], the proper targeting of mGluRs at synapses is essential for their synaptic functions. Regulation of mGluR trafficking would provide a powerful means to modulate the long-term synaptic plasticity of ionotropic glutamate and GABAA receptors, and other synaptic functions in which mGluRs are involved.

CONCLUSIONS

The knowledge about the roles of mGluRs in glutamate and GABAA receptor trafficking can provide a basis for treating many central nervous system diseases, and facilitate potential clinical uses of mGluR agonists/antagonists for such treatments. The challenges in the future will be to establish the specific molecular mechanisms involved in the biochemical signaling cascades for group I mGluRs in the regulation of the trafficking of the ionotropic receptors, to determine the structural determinants underlying interaction between mGluRs and ionotropic receptors at postsynaptic compartments, and to identify the physiological and pathological factors which can contribute to the alterations of mGluRs’ interaction with other ionotropic receptors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (project number 14842 and 01580), Svenska Lakaresallskapet and Goteborgs Lakaresallskap.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alagarsamy S, Marino MJ, Rouse ST, Gereau RW, 4th, Heinemann SF, Conn PJ. Activation of NMDA receptors reverses desensitization of mGluR5 in native and recombinant systems. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:234–40. doi: 10.1038/6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright TD, Jessell TM, Kandel ER, Posner MI. Neural science: a century of progress and the mysteries that remain. Neuron. 2000;25:S1–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80912-5. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ango F, Robbe D, Tu JC, Xiao B, Worley PF, Pin JP, Bockaert J, Fagni L. Homer-dependent cell surface expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5 in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:323–9. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anwyl R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: electrophysiological properties and role in plasticity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;29:83–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barria A, Malinow R. Subunit-specific NMDA receptor trafficking to synapses. Neuron. 2002;35:345–53. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00776-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayer KU, De Koninck P, Leonard AS, Hell JW, Schulman H. Interaction with the NMDA receptor locks CaMKII in an active conformation. Nature. 2001;411:801–5. doi: 10.1038/35081080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beattie EC, Carroll RC, Yu X, Morishita W, Yasuda H, von Zastrow M, Malenka RC. Regulation of AMPA receptor endocytosis by a signaling mechanism shared with LTD. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1291–300. doi: 10.1038/81823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beattie EC, Stellwagen D, Morishita W, Bresnahan JC, Ha BK, Von Zastrow M, Beattie MS, Malenka RC. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFalpha. Science. 2002;295:2282–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedford FK, Kittler JT, Muller E, Thomas P, Uren JM, Merlo D, Wisden W, Triller A, Smart TG, Moss SJ. GABA(A) receptor cell surface number and subunit stability are regulated by the ubiquitin-like protein Plic-1. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:908–16. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berberich S, Punnakkal P, Jensen V, Pawlak V, Seeburg PH, Hvalby O, Kohr G. Lack of NMDA receptor subtype selectivity for hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6907–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1905-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV, Godin C, Anborgh PH, Dale LB, Poulter MO, Ferguson SS. Ral and phospholipase D2-dependent pathway for constitutive metabotropic glutamate receptor endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8752–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3155-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–9. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bortolotto ZA, Fitzjohn SM, Collingridge GL. Roles of metabotropic glutamate receptors in LTP and LTD in the hippocampus. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brackmann M, Zhao C, Kuhl D, Manahan-Vaughan D, Braunewell KH. MGluRs regulate the expression of neuronal calcium sensor proteins NCS-1 and VILIP-1 and the immediate early gene arg3.1/arc in the hippocampus in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:1073–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braithwaite SP, Meyer G, Henley JM. Interactions between AMPA receptors and intracellular proteins. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:919–30. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2003;40:361–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruckner K, Pablo Labrador J, Scheiffele P, Herb A, Seeburg PH, Klein R. EphrinB ligands recruit GRIP family PDZ adaptor proteins into raft membrane microdomains. Neuron. 1999;22:511–24. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, El-Husseini A, Tomita S, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Stargazin differentially controls the trafficking of alpha-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate and kainate receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:703–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choquet D, Triller A. The role of receptor diffusion in the organization of the postsynaptic membrane. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:251–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciruela F, Soloviev MM, Chan WY, McIlhinney RA. Homer-1c/Vesl-1L modulates the cell surface targeting of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1alpha: evidence for an anchoring function. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:36–50. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen AS, Abraham WC. Facilitation of long-term potentiation by prior activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:953–62. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen AS, Raymond CR, Abraham WC. Priming of long-term potentiation induced by activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors coupled to phospholipase C. Hippocampus. 1998;8:160–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:2<160::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:952–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conn PJ. Physiological roles and therapeutic potential of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:12–21. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coussen F, Normand E, Marchal C, Costet P, Choquet D, Lambert M, Mege RM, Mulle C. Recruitment of the kainate receptor subunit glutamate receptor 6 by cadherin/catenin complexes. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6426–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06426.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dale LB, Bhattacharya M, Seachrist JL, Anborgh PH, Ferguson SS. Agonist-stimulated and tonic internalization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a in human embryonic kidney 293 cells: agonist-stimulated endocytosis is beta-arrestin1 isoformspecific. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:1243–53. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De La Rue SA, Henley JM. Proteins involved in the trafficking and functional synaptic expression of AMPA and KA receptors. Scientific World J. 2002;2:461–82. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2002.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doherty AJ, Coutinho V, Collingridge GL, Henley JM. Rapid internalization and surface expression of a functional, fluorescently tagged G-protein-coupled glutamate receptor. Biochem J. 1999;341 (Pt 2:415–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doherty AJ, Palmer MJ, Bortolotto ZA, Hargreaves A, Kingston AE, Ornstein PL, Schoepp DD, Lodge D, Collingridge GL. A novel, competitive mGlu(5) receptor antagonist ( LY344545) blocks DHPG-induced potentiation of NMDA responses but not the induction of LTP in rat hippocampal slices. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:239–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehrengruber MU, Kato A, Inokuchi K, Hennou S. Homer/Vesl proteins and their roles in CNS neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2004;29:213–27. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:3:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong DK, Rao A, Crump FT, Craig AM. Rapid synaptic remodeling by protein kinase C: reciprocal translocation of NMDA receptors and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2153–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02153.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fourgeaud L, Bessis AS, Rossignol F, Pin JP, Olivo-Marin JC, Hemar A. The metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 is endocytosed by a clathrin-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12222–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francesconi W, Cammalleri M, Sanna PP. The metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is necessary for late-phase long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region. Brain Res. 2004;1022:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii S, Mikoshiba K, Kuroda Y, Ahmed TM, Kato H. Cooperativity between activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and NMDA receptors in the induction of LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Neurosci Res. 2003;46:509–21. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(03)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaiarsa JL, Caillard O, Ben-Ari Y. Long-term plasticity at GABAergic and glycinergic synapses: mechanisms and functional significance. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:564–70. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groc L, Heine M, Cognet L, Brickley K, Stephenson FA, Lounis B, Choquet D. Differential activity-dependent regulation of the lateral mobilities of AMPA and NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:695–6. doi: 10.1038/nn1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grosshans DR, Clayton DA, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. LTP leads to rapid surface expression of NMDA but not AMPA receptors in adult rat CA1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nn779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gubellini P, Saulle E, Centonze D, Costa C, Tropepi D, Bernardi G, Conquet F, Calabresi P. Corticostriatal LTP requires combined mGluR1 and mGluR5 activation. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:8–16. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henley JM. Proteins interactions implicated in AMPA receptor trafficking: a clear destination and an improving route map. Neurosci Res. 2003;45:243–54. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00229-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henze DA, Urban NN, Barrionuevo G. The multifarious hippocampal mossy fiber pathway: a review. Neuroscience. 2000;98:407–27. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hermans E, Challiss RA. Structural, signalling and regulatory properties of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptors: prototypic family C G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem J. 2001;359:465–84. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herring D, Huang R, Singh M, Dillon GH, Leidenheimer NJ. PKC modulation of GABAA receptor endocytosis and function is inhibited by mutation of a dileucine motif within the receptor beta 2 subunit. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:181–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heuss C, Gerber U. G-protein-independent signaling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:469–75. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heuss C, Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. G-protein-independent signaling mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1070–7. doi: 10.1038/15996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirbec H, Francis JC, Lauri SE, Braithwaite SP, Coussen F, Mulle C, Dev KK, Coutinho V, Meyer G, Isaac JT, Collingridge GL, Henley JM. Rapid and differential regulation of AMPA and kainate receptors at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses by PICK1 and GRIP. Neuron. 2003;37:625–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang CC, You JL, Wu MY, Hsu KS. Rap1-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation facilitates AMPA receptor trafficking via the GDI.Rab5 complex. Potential role in (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycene-induced long term depression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12286–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huettner JE. Kainate receptors and synaptic transmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:387–407. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iacovelli L, Salvatore L, Capobianco L, Picascia A, Barletta E, Storto M, Mariggio S, Sallese M, Porcellini A, Nicoletti F, De Blasi A. Role of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 and beta-arrestin 1 in agonist-stimulated metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 internalization and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12433–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Isaac JT, Mellor J, Hurtado D, Roche KW. Kainate receptor trafficking: physiological roles and molecular mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;104:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaskolski F, Coussen F, Mulle C. Subcellular localization and trafficking of kainate receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaskolski F, Coussen F, Nagarajan N, Normand E, Rosenmund C, Mulle C. Subunit composition and alternative splicing regulate membrane delivery of kainate receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2506–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5116-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia Z, Lu YM, Agopyan N, Roder J. Gene targeting reveals a role for the glutamate receptors mGluR5 and GluR2 in learning and memory. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:771–81. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kitano J, Kimura K, Yamazaki Y, Soda T, Shigemoto R, Nakajima Y, Nakanishi S. Tamalin, a PDZ domain-containing protein, links a protein complex formation of group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor cytohesins. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1280–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01280.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kittler JT, Moss SJ. Modulation of GABAA receptor activity by phosphorylation and receptor trafficking: implications for the efficacy of synaptic inhibition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:341–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiyama Y, Manabe T, Sakimura K, Kawakami F, Mori H, Mishina M. Increased thresholds for long-term potentiation and contextual learning in mice lacking the NMDA-type glutamate receptor epsilon1 subunit. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6704–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06704.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kohr G, Jensen V, Koester HJ, Mihaljevic AL, Utvik JK, Kvello A, Ottersen OP, Seeburg PH, Sprengel R, Hvalby O. Intracellular domains of NMDA receptor subtypes are determinants for long-term potentiation induction. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10791–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10791.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lan JY, Skeberdis VA, Jover T, Grooms SY, Lin Y, Araneda RC, Zheng X, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Protein kinase C modulates NMDA receptor trafficking and gating. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:382–90. doi: 10.1038/86028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lan JY, Skeberdis VA, Jover T, Zheng X, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 accelerates NMDA receptor trafficking. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6058–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06058.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leil TA, Chen ZW, Chang CS, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor-associated protein traffics GABAA receptors to the plasma membrane in neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11429–38. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3355-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin JW, Ju W, Foster K, Lee SH, Ahmadian G, Wyszynski M, Wang YT, Sheng M. Distinct molecular mechanisms and divergent endocytotic pathways of AMPA receptor internalization. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1282–90. doi: 10.1038/81814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu F, Ma XH, Ule J, Bibb JA, Nishi A, DeMaggio AJ, Yan Z, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and casein kinase 1 by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11062–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191353898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu F, Wan Q, Pristupa ZB, Yu XM, Wang YT, Niznik HB. Direct protein-protein coupling enables crosstalk between dopamine D5 and gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors. Nature. 2000;403:274–80. doi: 10.1038/35002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu F, Virshup DM, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Mechanism of regulation of casein kinase I activity by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45393–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204499200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lledo PM, Zhang X, Sudhof TC, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic membrane fusion and long-term potentiation. Science. 1998;279:399–403. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu W, Man H, Ju W, Trimble WS, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2001;29:243–54. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu YM, Jia Z, Janus C, Henderson JT, Gerlai R, Wojtowicz JM, Roder JC. Mice lacking metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 show impaired learning and reduced CA1 long-term potentiation (LTP) but normal CA3 LTP. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5196–205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05196.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu YM, Mansuy IM, Kandel ER, Roder J. Calcineurin-mediated LTD of GABAergic inhibition underlies the increased excitability of CA1 neurons associated with LTP. Neuron. 2000;26:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luis Albasanz J, Fernandez M, Martin M. Internalization of metabotropic glutamate receptor in C6 cells through clathrin-coated vesicles. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;99:54–66. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luscher B, Keller CA. Regulation of GABAA receptor trafficking, channel activity, and functional plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;102:195–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation--a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–4. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malinow R, Mainen ZF, Hayashi Y. LTP mechanisms: from silence to four-lane traffic. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:352–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:103–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manahan-Vaughan D, Ngomba RT, Storto M, Kulla A, Catania MV, Chiechio S, Rampello L, Passarelli F, Capece A, Reymann KG, Nicoletti F. An increased expression of the mGlu5 receptor protein following LTP induction at the perforant path-dentate gyrus synapse in freely moving rats. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mangiavacchi S, Wolf ME. Stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, AMPA receptors or metabotropic glutamate receptors leads to rapid internalization of AMPA receptors in cultured nucleus accumbens neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:649–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Massey PV, Johnson BE, Moult PR, Auberson YP, Brown MW, Molnar E, Collingridge GL, Bashir ZI. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in cortical long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7821–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Minami I, Kengaku M, Smitt PS, Shigemoto R, Hirano T. Long-term potentiation of mGluR1 activity by depolarization-induced Homer1a in mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1023–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Molnar E, Isaac JT. Developmental and activity dependent regulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors at synapses. Scientific World J. 2002;2:27–47. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2002.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mu Y, Otsuka T, Horton AC, Scott DB, Ehlers MD. Activity-dependent mRNA splicing controls ER export and synaptic delivery of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2003;40:581–94. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00676-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mundell SJ, Matharu AL, Pula G, Roberts PJ, Kelly E. Agonist-induced internalization of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a is arrestin- and dynamin-dependent. J Neurochem. 2001;78:546–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mundell SJ, Pula G, Carswell K, Roberts PJ, Kelly E. Agonist-induced internalization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1A: structural determinants for protein kinase C- and G protein-coupled receptor kinase-mediated internalization. J Neurochem. 2003;84:294–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mundell SJ, Pula G, More JC, Jane DE, Roberts PJ, Kelly E. Activation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits the desensitization and internalization of metabotropic glutamate receptors 1a and 1b. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1507–16. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Naie K, Manahan-Vaughan D. Regulation by metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 of LTP in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats: relevance for learning and memory formation. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:189–98. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Naie K, Manahan-Vaughan D. Pharmacological antagonism of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 regulates long-term potentiation and spatial reference memory in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats via N-methyl-D-aspartate and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:411–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Naisbitt S, Kim E, Tu JC, Xiao B, Sala C, Valtschanoff J, Weinberg RJ, Worley PF, Sheng M. Shank, a novel family of postsynaptic density proteins that binds to the NMDA receptor/PSD-95/GKAP complex and cortactin. Neuron. 1999;23:569–82. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Contrasting properties of two forms of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1995;377:115–8. doi: 10.1038/377115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nosyreva ED, Huber KM. Developmental switch in synaptic mechanisms of hippocampal metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2992–3001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nusser Z, Hajos N, Somogyi P, Mody I. Increased number of synaptic GABA(A) receptors underlies potentiation at hippocampal inhibitory synapses. Nature. 1998;395:172–7. doi: 10.1038/25999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Orlando LR, Dunah AW, Standaert DG, Young AB. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 in striatal neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:161–73. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patenaude C, Chapman CA, Bertrand S, Congar P, Lacaille JC. GABAB receptor-and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent cooperative long-term potentiation of rat hippocampal GABAA synaptic transmission. J Physiol. 2003;553:155–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Perez-Otano I, Ehlers MD. Homeostatic plasticity and NMDA receptor trafficking. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Priel A, Kolleker A, Ayalon G, Gillor M, Osten P, Stern-Bach Y. Stargazin reduces desensitization and slows deactivation of the AMPA-type glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2682–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4834-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Racz B, Blanpied TA, Ehlers MD, Weinberg RJ. Lateral organization of endocytic machinery in dendritic spines. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:917–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ren Z, Riley NJ, Garcia EP, Sanders JM, Swanson GT, Marshall J. Multiple trafficking signals regulate kainate receptor KA2 subunit surface expression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6608–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Roche KW, Standley S, McCallum J, Dune Ly C, Ehlers MD, Wenthold RJ. Molecular determinants of NMDA receptor internalization. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:794–802. doi: 10.1038/90498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Roche KW, Tu JC, Petralia RS, Xiao B, Wenthold RJ, Worley PF. Homer 1b regulates the trafficking of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25953–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rush AM, Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)-dependent long-term depression mediated via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is inhibited by previous high-frequency stimulation and activation of mGluRs and protein kinase C in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6121–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06121.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Savtchenko LP, Korogod SM, Rusakov DA. Electrodiffusion of synaptic receptors: a mechanism to modify synaptic efficacy? Synapse. 2000;35:26–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200001)35:1<26::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Selig DK, Hjelmstad GO, Herron C, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Independent mechanisms for long-term depression of AMPA and NMDA responses. Neuron. 1995;15:417–26. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Semyanov A. Cell type specificity of GABA(A) receptor mediated signaling in the hippocampus. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2003;2:240–7. doi: 10.2174/1568007033482832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Serge A, Fourgeaud L, Hemar A, Choquet D. Active surface transport of metabotropic glutamate receptors through binding to microtubules and actin flow. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:5015–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sheng M, Sala C. PDZ domains and the organization of supramolecular complexes. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shinoda Y, Kamikubo Y, Egashira Y, Tominaga-Yoshino K, Ogura A. Repetition of mGluR-dependent LTD causes slowly developing persistent reduction in synaptic strength accompanied by synapse elimination. Brain Res. 2005;1042:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Snyder EM, Philpot BD, Huber KM, Dong X, Fallon JR, Bear MF. Internalization of ionotropic glutamate receptors in response to mGluR activation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1079–85. doi: 10.1038/nn746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stellwagen D, Beattie EC, Seo JY, Malenka RC. Differential regulation of AMPA receptor and GABA receptor trafficking by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3219–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4486-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sugiyama H, Ito I, Hirono C. A new type of glutamate receptor linked to inositol phospholipid metabolism. Nature. 1987;325:531–3. doi: 10.1038/325531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Svoboda K, Mainen ZF. Synaptic [Ca2+]: intracellular stores spill their guts. Neuron. 1999;22:427–30. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–9. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Teyler TJ, Cavus I, Coussens C, DiScenna P, Grover L, Lee YP, Little Z. Multideterminant role of calcium in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Hippocampus. 1994;4:623–34. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tomita S, Adesnik H, Sekiguchi M, Zhang W, Wada K, Howe JR, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Stargazin modulates AMPA receptor gating and trafficking by distinct domains. Nature. 2005;435:1052–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Torres R, Firestein BL, Dong H, Staudinger J, Olson EN, Huganir RL, Bredt DS, Gale NW, Yancopoulos GD. PDZ proteins bind, cluster, and synaptically colocalize with Eph receptors and their ephrin ligands. Neuron. 1998;21:1453–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tovar KR, Westbrook GL. Mobile NMDA receptors at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2002;34:255–64. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tu JC, Xiao B, Naisbitt S, Yuan JP, Petralia RS, Brakeman P, Doan A, Aakalu VK, Lanahan AA, Sheng M, Worley PF. Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins. Neuron. 1999;23:583–92. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80810-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wan Q, Xiong ZG, Man HY, Ackerley CA, Braunton J, Lu WY, Becker LE, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Recruitment of functional GABA(A) receptors to postsynaptic domains by insulin. Nature. 1997;388:686–90. doi: 10.1038/41792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.van Rijnsoever C, Sidler C, Fritschy JM. Internalized GABA-receptor subunits are transferred to an intracellular pool associated with the postsynaptic density. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:327–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang Q, Liu L, Pei L, Ju W, Ahmadian G, Lu J, Wang Y, Liu F, Wang YT. Control of synaptic strength, a novel function of Akt. Neuron. 2003;38:915–28. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wenthold RJ, Prybylowski K, Standley S, Sans N, Petralia RS. Trafficking of NMDA receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:335–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wong RW, Setou M, Teng J, Takei Y, Hirokawa N. Overexpression of motor protein KIF17 enhances spatial and working memory in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222371099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Synaptically stimulated induction of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression and depotentiation is inhibited by prior activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and protein kinase C. Neuroscience. 2004;123:507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Xiao B, Tu JC, Worley PF. Homer: a link between neural activity and glutamate receptor function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:370–4. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Xiao MY, Wasling P, Hanse E, Gustafsson B. Creation of AMPA-silent synapses in the neonatal hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:236–43. doi: 10.1038/nn1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Xiao MY, Zhou Q, Nicoll RA. Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation causes a rapid redistribution of AMPA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:664–71. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yan S, Sanders JM, Xu J, Zhu Y, Contractor A, Swanson GT. A C-terminal determinant of GluR6 kainate receptor trafficking. J Neurosci. 2004;24:679–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yeckel MF, Kapur A, Johnston D. Multiple forms of LTP in hippocampal CA3 neurons use a common postsynaptic mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:625–33. doi: 10.1038/10180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zakharenko SS, Zablow L, Siegelbaum SA. Altered presynaptic vesicle release and cycling during mGluRdependent LTD. Neuron. 2002;35:1099–110. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00898-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zho WM, You JL, Huang CC, Hsu KS. The group I metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist (S)-3,5dihydroxyphenylglycine induces a novel form of depotentiation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8838–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08838.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhou Q, Xiao M, Nicoll RA. Contribution of cytoskeleton to the internalization of AMPA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1261–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031573798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zucker RS. Calcium- and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:305–13. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]