There is little doubt that elevation of plasma total homocysteine is associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Over the past two decades, many large prospective studies have established that hyperhomocysteinemia predicts for an increased relative risk of coronary events, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and death.1,2 Hyperhomocysteinemia also has been shown to produce abnormalities of vascular structure and function in animal models.3 Paradoxically, however, several intervention trials have failed to demonstrate any clinical benefit from homocysteine-lowering therapy.4-8 What is the explanation for this paradox?

One possibility is that hyperhomocysteinemia is a clinically important risk factor only when plasma total homocysteine is elevated to extremely high levels. The hypothesis that homocysteine is a cardiovascular risk factor first arose from clinical and pathological observations in children and young adults with hereditary homocystinuria. 9 If untreated, these individuals develop severe hyperhomocysteinemia, with plasma total homocysteine levels greater than 100 μmol/L, and they have a high risk of developing pathological vascular lesions and thromboembolic events at a young age.10 When placed on homocysteine-lowering therapy (high doses of vitamin B6, vitamin B12, folic acid, and/or betaine, along with dietary methionine restriction), their risk of adverse vascular events decreases markedly.11 Improvement in vascular outcome occurs despite a moderate level of residual hyperhomocysteinemia.

In contrast to the clear clinical benefit of homocysteine-lowering therapy in severe hyperhomocysteinemia, its potential role in mild hyperhomocysteinemia remains unproven. All of the recent intervention trials of homocysteine-lowering therapy have been performed in subjects with relatively mild hyperhomocysteinemia (plasma total homocysteine levels between 10 and 30 μmol/L). The negative results of these trials may indicate that mild hyperhomocysteinemia is not a causative risk factor or that the statistical power of the trials was insufficient to exclude a small clinical benefit. It is also possible that homocysteine-lowering therapy with combinations of B vitamins produces some adverse vascular effect that masks the benefit of lowered homocysteine.6 Larger trials with longer durations of homocysteine-lowering therapy may be necessary to completely settle this issue, although some closure may come from a planned collaborative meta-analysis.12 Trials of population interventions to lower homocysteine as a primary prevention strategy also have been proposed.13,14

As we await more clinical trial data, the possibility must be considered that mild hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with increased vascular risk not because it is directly involved in the pathogenesis of vascular disease but because it is a marker of another deleterious process. An obvious candidate for this other process is chronic kidney disease. Renal dysfunction is a recognized risk factor for increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The relationship between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk extends in a graded fashion from mild renal impairment to end-stage renal disease.15 The kidney also plays a major role in homocysteine metabolism.16 Plasma total homocysteine increases as renal function declines; it is elevated in the vast majority of patients with end-stage renal disease. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is a strong determinant of plasma homocysteine concentration, even in individuals with very mild renal dysfunction.17 The strong correlation between homocysteine and GFR led Andrew Bostom to suggest almost 10 years ago that elevated homocysteine may be an epiphenomenon of renal dysfunction, or “expensive creatinine.”18

In this issue of ATVB, a new paper by Potter et al. provides a nice confirmation of the relationship between homocysteine and renal function. The authors performed a post-hoc analysis of data from 173 participants in one of the large international homocysteine-lowering trials, the Vitamins to Prevent Stroke (VITATOPS) trial. VITATOPS was designed to determine the safety and efficacy of daily supplementation with B vitamins (2 mg folic acid, 25 mg vitamin B6, and 0.5 mg vitamin B12) to prevent secondary vascular events in patients with a recent stroke or transient ischemic attack.19 The cross-sectional analysis by Potter et al. included an assessment of cystatin C (a sensitive marker of GFR), total homocysteine, and two surrogate markers of vascular risk, carotid artery intima media thickness (IMT) and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD), in subjects who had been treated with B vitamins or placebo for at least two years. As expected, a strong linear relationship between total homocysteine and cystatin C was observed in both the vitamin and placebo groups. Both total homocysteine and cystatin C were found to correlate significantly with the vascular endpoints (carotid IMT and brachial FMD). Only cystatin C, however, was an independent predictor of FMD. Importantly, adjustment for renal function eliminated the relationship between total homocysteine and both IMT and FMD.

The data shown in Figure 2 of the paper by Potter et al. provide a particularly compelling illustration of the effects of vitamin supplementation on the relationship between homocysteine and renal function. In a subgroup of 132 subjects for which both baseline and post-treatment serum samples were assayed for homocysteine and cystatin C, a significant separation of the regression lines was observed in the post-treatment samples. This figure clearly shows that treatment with vitamins lowered total homocysteine without influencing the strong relationship between homocysteine and GFR. Coupled with the observation that there was no significant difference in FMD between the vitamin and placebo groups, these data imply that renal dysfunction is a stronger determinant of vascular function than is homocysteine. By extension, these findings suggest that impaired renal function may account for a large component of the epidemiological association between mild hyperhomocysteinemia and increased cardiovascular risk.

On first glance, the idea that elevated homocysteine may be a marker of renal dysfunction rather than a mediator of vascular disease appears to contradict a considerable amount of evidence from animal models of hyperhomocysteinemia. In mice and other animals, hyperhomocysteinemia leads to endothelial dysfunction, vascular hypertrophy, accelerated thrombosis, and predisposition to atherosclerosis.3 Similar vascular phenotypes are observed when hyperhomocysteinemia is induced by a variety of different genetic or dietary approaches. These findings in animal models suggest, but do not prove, that elevated homocysteine itself is a causative factor in vascular dysfunction. Renal function was not measured in most of these animal studies, and it is conceivable that the methods used to induce hyperhomocysteinemia may have caused alterations in GFR. The possibility cannot be excluded, therefore, that renal dysfunction might account for some of the adverse vascular phenotypes seen in hyperhomocysteinemic animals.

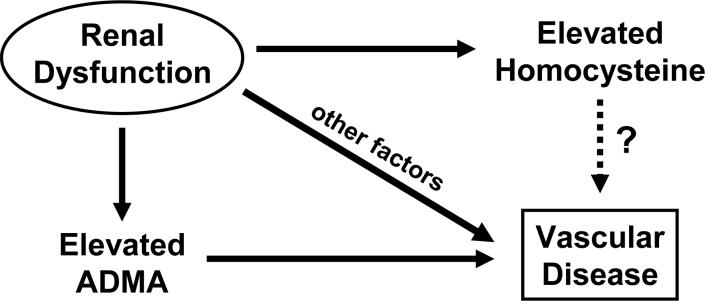

Several mechanisms have been proposed to cause vascular pathophysiology in chronic kidney disease. These include endothelial dysfunction, activation of the reninangiotensin system, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and altered calcium homeostasis. 15 One potential mechanism for endothelial dysfunction in renal disease is the accumulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase. Like plasma total homocysteine, plasma ADMA is inversely related to GFR and is predictive of increased mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease.20 Some of the potential mechanistic relationships between renal dysfunction, ADMA, homocysteine, and vascular disease are summarized in the Figure.

Possible mechanistic relationships between renal dysfunction and vascular disease. Impaired renal function causes elevation of homocysteine and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), both of which are associated with an increased risk of vascular disease. Homocysteine may be a direct mediator of vascular disease or a marker of ADMA or other etiological factors related to renal dysfunction.

Although it suggests a potential explanation for the homocysteine paradox, the paper by Potter et al. represents a relatively small post-hoc analysis that has several limitations. Unfortunately, carotid IMT and brachial FMD were not assessed at baseline, before initiating treatment with vitamins or placebo. The VITATOPS trial is still ongoing, and we do not yet have access to data on hard clinical endpoints such as recurrent stroke, coronary events, or venous thromboembolism. It will be necessary to confirm the relationships between homocysteine, renal function, and vascular outcomes in larger data sets from VITATOPS and other trials before concluding that mild hyperhomocysteinemia is simply a marker of decreased renal function rather than an independent vascular risk factor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an un-copyedited author manuscript that was accepted for publication in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, copyright The American Heart Association. This may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the “Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials” (section 107, title 17, U.S. Code) without prior permission of the copyright owner, The American Heart Association. The final copyedited article, which is the version of record, can be found at Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. The American Heart Association disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the National Institutes of Health or other parties.

References

- 1.Homocysteine Studies Collaboration Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2015–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.den Heijer M, Lewington S, Clarke R. Homocysteine, MTHFR and risk of venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:292–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dayal S, Lentz SR. Role of redox reactions in the vascular phenotype of hyperhomocysteinemic animals. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1899–909. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ, Sides EG, Wang CH, Stampfer M. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:565–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lonn E, Yusuf S, Arnold MJ, Sheridan P, Pogue J, Micks M, McQueen MJ, Probstfield J, Fodor G, Held C, Genest J., Jr Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1567–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonaa KH, Njolstad I, Ueland PM, Schirmer H, Tverdal A, Steigen T, Wang H, Nordrehaug JE, Arnesen E, Rasmussen K. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1578–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.den Heijer M, Willems HP, Blom HJ, Gerrits WB, Cattaneo M, Eichinger S, Rosendaal FR, Bos GM. Homocysteine lowering by B vitamins and the secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Blood. 2007;109:139–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamison RL, Hartigan P, Kaufman JS, Goldfarb DS, Warren SR, Guarino PD, Gaziano JM. Effect of homocysteine lowering on mortality and vascular disease in advanced chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1163–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCully KS. Homocysteine, vitamins, and vascular disease prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1563S–8S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1563S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mudd SH, Skovby F, Levy HL, Pettigrew KD, Wilcken B, Pyeritz RE, Andria G, Boers GHJ, Bromberg IL, Cerone R, Fowler B, Grobe H, Schmidt H, Schweitzer L. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:1–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yap S, Boers GH, Wilcken B, Wilcken DE, Brenton DP, Lee PJ, Walter JH, Howard PM, Naughten ER. Vascular outcome in patients with homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency treated chronically: a multicenter observational study. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2080–5. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke R, Armitage J, Lewington S, Collins R. Homocysteine-lowering trials for prevention of vascular disease: protocol for a collaborative meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1575–81. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Q, Botto LD, Erickson JD, Berry RJ, Sambell C, Johansen H, Friedman JM. Improvement in stroke mortality in Canada and the United States, 1990 to 2002. Circulation. 2006;113:1335–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.570846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Qin X, Demirtas H, Li J, Mao G, Huo Y, Sun N, Liu L, Xu X. Efficacy of folic acid supplementation in stroke prevention: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:1876–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60854-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiffrin EL, Lipman ML, Mann JF. Chronic kidney disease: effects on the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2007;116:85–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman AN, Bostom AG, Selhub J, Levey AS, Rosenberg IH. The kidney and homocysteine metabolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2181–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bostom AG, Gohh RY, Bausserman L, Hakas D, Jacques PF, Selhub J, Dworkin L, Rosenberg IH. Serum cystatin C as a determinant of fasting total homocysteine levels in renal transplant recipients with a normal serum creatinine. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1999;10:164–6. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V101164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostom AG. Homocysteine: “Expensive creatinine” or important, modifiable risk factor for arteriosclerotic outcomes in renal transplant recipients? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2000;11:149–51. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V111149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The VITATOPS (Vitamins to Prevent Stroke) Trial: rationale and design of an international, large, simple, randomised trial of homocysteine-lowering multivitamin therapy in patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:120–6. doi: 10.1159/000047761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van GC, Nanayakkara PW, Stehouwer CD. Homocysteine and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): biochemically linked but differently related to vascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1683–7. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]