Abstract

Tetraethylammonium (TEA+) is widely used for reversible blockade of K channels in many preparations. We noticed that intracellular perfusion of voltage-clamped squid giant axons with a solution containing K+ and TEA+ irreversibly decreased the potassium current when there was no K+ outside. Five minutes of perfusion with 20 mM TEA+, followed by removal of TEA+, reduced potassium current to <5% of its initial value. The irreversible disappearance of K channels with TEA+ could be prevented by addition of ≥ 10 mM K+ to the extracellular solution. The rate of disappearance of K channels followed first-order kinetics and was slowed by reducing the concentration of TEA+. Killing is much less evident when an axon is held at −110 mV to tightly close all of the channels. The longer-chain TEA+ derivative decyltriethylammonium (C10+) had irreversible effects similar to TEA+. External K+ also protected K channels against the irreversible action of C10+. It has been reported that removal of all K+ internally and externally (dekalification) can result in the disappearance of K channels, suggesting that binding of K+ within the pore is required to maintain function. Our evidence further suggests that the crucial location for K+ binding is external to the (internal) TEA+ site and that TEA+ prevents refilling of this location by intracellular K+. Thus in the absence of extracellular K+, application of TEA+ (or C10+) has effects resembling dekalification and kills the K channels.

Keywords: dekalification, channel block, decyltriethylammonium, tetraethylammonium

Voltage-gated K channels are widespread transmembrane proteins that open in response to depolarization of the membrane (1). In excitable cells they serve the crucial function of repolarizing the membrane to its resting voltage after an action potential. Tetraethylammonium (TEA+) is a small organic cation, about the size of a hydrated K+ ion, that is very useful as a blocker of many K+ channels. In squid axons, TEA+ blocks only from the inside. Presumably, it occupies a vestibule that is large enough to accept a hydrated K+ ion, but TEA+, unlike K+, cannot pass through a narrower part of the pore and thus blocks rather than permeating.

It has been known since 1970 that removal of K+ ions from both sides of the membrane of squid giant axons renders its K channels permanently nonfunctional (2). The exact mechanism is not well understood (see Discussion). Further studies have confirmed the earlier observations in the squid (3) and Shaker B potassium channels (ref. 4 and A.M. and C.M.A., unpublished observations), although some mammalian K channels have been reported to lose their selectivity in the absence of K+ and become Na+ permeant (5–7) without losing function altogether.

During the course of experiments that involved perfusion of squid axons with an internal K+ solution containing TEA+, we noticed that the K+ current (IK) recovered after TEA+ only if K+ was present outside. After ruling out the possibilities of chemical contamination and degradation of TEA+, we were forced to conclude that TEA+ had in some way made the K channels nonfunctional. The results suggest that TEA+ denies access by internal K+ ions to a binding site in the external part of the channel, effectively dekalifying this site and killing the channel.

METHODS

Experiments were performed at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA, on voltage-clamped internally perfused giant axons of the squid Loligo pealei at 8°C. The main extracellular solution contained 200 mM NaCl, 100 mM CaCl2, 10 mM TRIZMA (pH 7.0), and enough tetramethylammonium chloride (TMA+) to obtain an osmolality of 1,000 milliosmoles (mOsmol)/kg. When indicated, 10 or 20 mM KCl was included in the extracellular solution and TMA was reduced to maintain the osmolality at 1,000 mOsmol/kg. Extracellular solutions in the text are specified simply by their K+ concentration. The intracellular solution, referred to as //275KFG, contained 170 mM potassium glutamate, 50 mM KF, 55 mM Hepes (adjusted to pH 7.0 with KOH), and sucrose to increase the osmolality to 1,000 mOsmol/kg. Up to 20 mM tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA+) or 200 μM decyltriethylammonium bromide (C10+) was added to the internal solution when indicated. TEA+ was purchased from three sources. In one case, the TEA+ was recrystallized in the laboratory. C10+ was synthesized in the laboratory.

Currents recorded after voltage jumps were corrected for leak and capacitance.

RESULTS

TEA+ Irreversibly Abolishes Permeation Through K Channels in the Absence of External K+.

Normal membrane current in our ionic conditions is shown in Fig. 1A (Before TEA). The extracellular solution contained no added K+, and fiber was internally perfused with//275KFG. After a depolarizing voltage step there is a small outward (upward) transient of gating current (Ig), followed by an inward (downward) Na+ ionic current (INa), followed in turn by outward IK. Under these conditions INa and IK could be followed for long periods of time without significant change in their amplitudes (Fig. 1B). Internal perfusion of the axon with //275KFG+20 mM TEA+ blocked IK within seconds (Fig. 1 A and B). TEA+ also blocked about two-thirds of INa without affecting Ig. The reduction of INa by TEA+ was reversible and after a 5-min exposure to TEA+, INa promptly recovered to its original amplitude upon washout of TEA+. IK, on the other hand, never recovered in this experiment, and we found no way to make it recover (c.f., ref. 5).

Figure 1.

TEA+ irreversibly abolishes IK without affecting INa when external K+ is absent. (A) Membrane potential was stepped from −110 mV to 40 mV. In the trace labeled Before TEA, the voltage jump resulted in an outward Na channel gating current (Ig), immediately followed by an inward Na current (INa). INa inactivated leaving the slower activating outward potassium current (IK). Internal perfusion with 20 mM TEA+ completely blocked IK and reduced INa without affecting Ig (trace labeled In 20 mM TEA+). After washout of TEA+, which was applied for 5 min, INa fully recovered while IK remained absent (trace After TEA). (B) Time course of peak amplitudes of IK and INa of the experiment in A. Stable INa and IK can be recorded for long periods of time without significant decline in their amplitudes. Perfusion of 20 mM TEA+ completely blocked IK and reduced INa. Upon washout of TEA+, INa fully recovered, but IK remained absent. Experiment SE126A. (C) To test whether the irreversible effect of TEA+ on IK requires the opening and closing of K channels, an axon was clamped at −110 mV and perfused with 2 mM TEA+ (solid bars) with and without repeated 10-ms depolarizing pulses to 20 mV. IK fully recovered when no pulses were applied. Less than 45% recovered when the axon was repeatedly depolarized in the presence of TEA+. INa was not affected by either procedure. Experiment Au276A.

The data shown were obtained with a sample of freshly recrystallized TEA+. Similar results were obtained with TEA+ purchased from three sources, ruling out the possibility of chemical degradation or contamination. The preservation of Ig and INa point to a selective killing action of TEA+ on the K channels.

TEA+ Does Not Affect K Channels If They Are Kept Closed.

It has been shown that in the complete absence of K+, K channels are made nonfunctional only if they are opened and closed by depolarizing pulses (5). We tested whether the irreversible action of TEA+ on IK also required depolarization and channel opening. Fig. 1C shows one of several experiments in which the axon was held at −110 mV without depolarization while perfusing with //275 KFG+2 mM TEA. IK fully recovered when TEA+ was removed. During a second exposure to internal TEA+, the axon was repeatedly depolarized. On removal of TEA+, IK was only 45% of its preexposure level. Thus TEA+ does not kill K channels if the axon is maintained at −110 mV without depolarization.

External K+ Protects Against the Irreversible Actions of TEA+.

It is known that extracellular K+ protects both squid and Shaker B K channels when intracellular potassium ions are removed (2, 5). Does external K+ also protect K channels from the irreversible action of TEA+? We examined this by including 20 or 10 mM K+ in the extracellular solution prior to internal perfusion of the axon with 1 mM TEA+. As shown in Fig. 2A, IK almost completely recovered when the axon was perfused with 1 mM TEA+ for 5 min in the presence of 20 or 10 mM extracellular K+. In the same axon less than 18% of IK recovered in the absence of external K+ after a third 5-min perfusion with 1 mM TEA+ (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained in two other axons. The fact that external K+ ions protect the channels supports the idea that TEA+ kills by a process similar to dekalification.

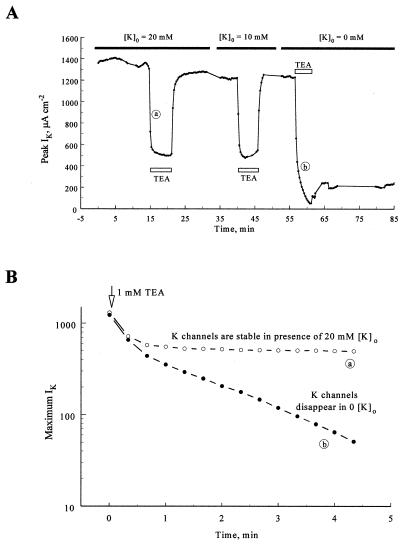

Figure 2.

Extracellular K+ ions protect K channels against the irreversible effect of TEA+. (A) Time course of maximum IK amplitudes after voltage jumps to 40 mV. The axon was bathed in a solution containing 20 mM K+ ions and perfused with 1 mM TEA+ (open bar) for 5 min. IK was reduced to ≈40% of its peak by TEA+ and almost fully recovered when TEA+ was washed out. IK also fully recovered from TEA+ when the extracellular solution contained 10 mM K+. When no K+ was added to the extracellular solution, however, less than 20% of the current recovered after exposure of the axon to TEA+. Experiment SE136A. (B) The rate of disappearance of K channels can be followed in the absence of extracellular potassium ions. IK amplitude is plotted on logarithmic scale, immediately after perfusion with 1 mM TEA+ in the presence (open circles) and absence (filled circles) of 20 mM TEA+. In both cases the amplitude of IK initially decreases rapidly and to the same extent as the channels are blocked by TEA+ (first two points). Once TEA+ had equilibrated, IK remained stable in the presence of 20 mM K+ outside, but it decreased exponentially in the absence of K+.

The rate of disappearance of K channels after exposure to 1 mM TEA+ in the absence of external K+ ions could be followed with relative ease in the previous experiment. As 1 mM TEA+ enters the axon, it initially blocks ≈65% of IK within 60 s in 20 mM external K+ (Fig. 2). The current remains reasonably constant thereafter. In the absence of external K+, the initial reduction of IK is similar (first two data points). IK, however, continues to decline in zero external K+ as K channels become nonfunctional. The disappearance of K channels has an exponential time course (Fig. 2B).

TEA+ Does Not Alter Activation Kinetics of Unmodified K Channels.

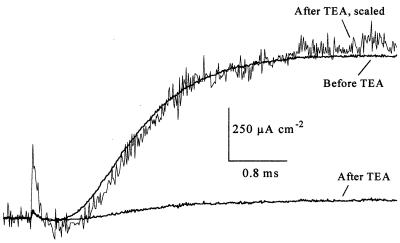

Fig. 3 shows that the activation time course of unmodified K channels is not affected by TEA+. An axon was perfused with 10 mM TEA+ for 5 min in the absence of external K+ ions. The amplitude of IK, after the washout of TEA+, was reduced to 8% of its control level. When arbitrarily scaled, the time course of the remaining IK was not markedly different from that prior to its exposure to TEA+. Thus the surviving channels seem completely unaffected.

Figure 3.

TEA+ does not affect activation kinetics of unmodified K channels. After perfusion of an axon with 10 mM TEA+, in the absence of extracellular potassium, IK decreased to 8% of its original amplitude. The kinetics of IK after application of TEA+ were not different from its kinetics prior to TEA+, as evident from the superimposition of the scaled IK on the control. Shown are voltage steps from a holding potential of −80 mV to 40 mV. Experiment AU306B.

C10+ Has a Dekalifying Action Similar to TEA+.

We used the longer-chain TEA+ derivative decyltriethylammonium (C10+) to see whether it also had an irreversible effect on K channels. C10+ at 200 μM was added to the //275KFG solution and perfused into an axon clamped at −110 mV. Two hundred seconds after the start of perfusion with C10+, the axon was depolarized to 40 mV for 20 ms, and the resulting current was recorded (Fig. 4). Like TEA+, C10+ is an open channel blocker with affinities for both K and Na channels. As shown in Fig. 4, C10+ reduced INa without affecting Ig. With a second voltage jump applied 1 s later, the amplitude of INa decreased further. This indicates that some of the C10+ molecules had stayed in Na channels as they closed upon repolarization from the first voltage step and were trapped there during the 1-s interval between pulses. C10+ also reduced IK. The kinetics of binding of C10+ molecules to K channels, however, are much slower than the kinetics of binding of TEA+ to K channels. Thus, although TEA+ simply reduces the amplitude of IK without affecting its shape, the slower kinetics of C10+ binding to K channels gives IK the appearance of an inactivating current (Fig. 4). The amplitude of IK, too, decreased further with the second voltage pulse, again suggesting that some of the K channels had trapped C10+ after the first pulse. After these two voltage steps C10+ was immediately washed out of the axon without any further voltage jumps. Upon thorough washout, the amplitude of IK was reduced by 33% while that of INa had completely recovered (Fig. 4). IK was completely killed by a subsequent 3-min perfusion with C10+ with many depolarizations applied (Fig. 5), whereas most of INa recovered upon C10+ washout. We also tested whether C10+ affected IK if the axon was not stimulated in the presence of C10+. In all three axons studied, we find that similar to TEA+, the irreversible action of C10+ on IK is more prominent if depolarizing voltage steps are applied to the axon.

Figure 4.

In the absence of external K+, C10+ has an irreversible effect on K channels similar to TEA+. (A) The trace labeled Before C10+ shows INa and IK after depolarization of an axon from −110 mV to 40 mV. The axon was perfused with 200 μM C10+ for 200 s and depolarized to 40 mV for 20 ms. C10+ rapidly reduced INa and more slowly blocked K channels as they opened, giving IK the appearance of an inactivating current. A second depolarizing voltage step delivered 1 s later yielded currents with similar kinetics although the amplitudes of INa and IK were reduced further. The smaller amplitude of INa and IK with the second pulse indicates that some channels had closed and had remained blocked with C10+ after the first depolarizing pulse in C10+. Immediately after the second depolarizing pulse, C10+ was washed out of the axon. Examination of INa and IK after thorough washout of C10+ showed that IK was reduced to 67% of its control value but INa fully recovered. Experiment SE136D.

Figure 5.

Repeated depolarization of an axon perfused with C10+ in the absence of external K+ ions irreversibly abolishes IK. The time course of INa and IK in a voltage-clamped axon (holding potential, −110 mV) are shown in an axon perfused with 200 μM C10+ for 5 min. The axon was repeatedly depolarized to 40 mV for 25 ms every 5 s while it was perfused with C10+. During this procedure the amplitude of IK declined to zero and the amplitude of INa declined to 8% of its control level. Upon washout of C10+, IK remained absent but most of INa recovered. Experiment SE136D.

DISCUSSION

The data presented show that TEA+ and C10+ irreversibly reduce IK when applied intracellularly in the absence of external K+. The irreversible action of these blockers on squid K channels resembles that which occurs when they are exposed to intra- and extracellular solutions devoid of K+ ions (2, 3).

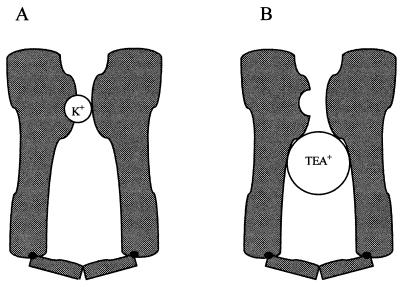

How does TEA+/C10+ exert an irreversible effect on K channels? It is clear that in the closed state K channels require the binding of one or more K+ ions to a site within the pore to avoid losing function. The simplest hypothesis is that TEA+/C10+ prevents refilling of this site by intracellular K+ ions (Fig. 6). This hypothesis is in agreement with many of the findings reported herein. For example, if channels are kept closed by clamping the axon at hyperpolarized potentials, the closed channel gates keep TEA+/C10+ from entering the pore, and the blocker has no effect. Further, because internal TEA+/C10+ hinders access of K+ ions only from inside, external K+ should be able to enter the pore and protect the channels despite the presence of an internal blocker. Indeed as little as 10 mM extracellular K+ protects K channels against TEA+ and C10+.

Figure 6.

TEA+ prevents refilling of the pore by internal K+. (A) During normal function K channels close with K+ bound to a site within the pore. (B) TEA+ prevents refilling of the pore by intracellular K+ and, in the absence of extracellular K+, results in dekalification and loss of channel function.

The hypothesis requires either that TEA+ or C10+ prevent refilling as the internally located gate(s) of the channel close. In the instant of closing, either TEA+/C10+ must get trapped inside the channel or they come out coincident with the closure of the gates, so that a K+ ion cannot get in the pore. Although the latter possibility seems unlikely, there is good evidence that these blockers can get trapped inside squid K channels (8). Trapping of C10+ molecules can be easily detected in the experiments reported herein (see Fig. 4). Trapping is known to be more likely if the pore is depleted of K+, as would be the case after depolarization with no external K+.

Interestingly, a somewhat similar effect of extracellular K+ and internal block has been shown in Shaker channels (9, 10). In this case, however, the channels quickly entered an inactivated state (C-type inactivated) in the absence of external K+, if the channel was blocked internally by the inactivation ball (N-type inactivation) or channel blockers, thus preventing refilling of an externally located site with K+. The relation of the killing seen here to C-type inactivation remains to be explored.

Why do K channels cease to function when they are dekalified? One possibility, proposed by Almers and Armstrong (3), is that the pore region of K channels may become energetically unstable because negatively charged residues in a K+ binding site are forced apart in the absence of the normally present counter charge, K+. Alternatively, it has been proposed by Gómez-Langunas (4) that K channels may be “locked” in a closed state or states in the absence of K+. Further experiments are necessary to better understand the fate of a K channel once its pore is depleted of K+. It would be of great interest to establish the identity of the K+ binding site that in the absence of K+ renders the channel nonfunctional and to determine whether this site is one of the K+ binding sites involved in permeation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Edward McCleskey and Gary Yellen for comments. This work was supported by Grant NS 12547.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IK

potassium current

- INa

Na current

- TEA+

tetraethylammonium

- C10+

decyltriethylammonium

- Ig

gating current

References

- 1.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2nd Ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandler W K, Meves H. J Physiol. 1970;211:623–652. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almers W, Armstrong C M. J Gen Physiol. 1980;75:61–78. doi: 10.1085/jgp.75.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gómez-Langunas F. J Physiol. 1997;499.1:3–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callahan M J, Korn S J. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:747–771. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.4.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korn S J, Ikeda S R. Science. 1995;269:410–412. doi: 10.1126/science.7618108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Y, Ikeda S R. J Physiol. 1993;468:441–461. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong C M. J Gen Physiol. 1971;58:413–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. Neuron. 1995;15(4):951–960. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. Science. 1996;271:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]