Abstract

The crystal structure of PCB 77 (3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl, C12H6Cl4), a dioxin-like PCB congener, is described. The dihedral angle of PCB 77 is 43.94(6)°, which is slightly larger than calculated or experimental dihedral angles of biphenyl derivatives in solution but smaller than experimental dihedral angles in the gas phase.

Keywords: Environmental contaminants, dioxin-like PCBs, dihedral angle, crystal structure

1. Introduction

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a class of persistent organic chemicals that were manufactured on an industrial scale until the late 70s (Hansen, 1999; Robertson and Hansen, 2001). Due to their high chemical stability, low flammability and other desirable physical properties, such as electrical insulation properties, they were used for technical applications such as hydraulic fluids, lubricants and as additives in paint, pesticides, sealants and plastics. In the United States, PCBs are still used as dielectric fluids in closed systems such as transformers and capacitors. Although their production is banned worldwide, PCBs continue to be a health concern due to their persistence in the environment, their tendency to bioaccumulate and to biomagnify, and their adverse effects in animal and epidemiological studies.

Technical PCB products are complex mixtures containing over 50 individual PCB congeners with different chemical structures and physicochemical properties. Depending on their three-dimensional structure, PCB congeners bind to different cellular target sites, and thus cause adverse effects by different mechanisms. For example, PCB congeners with ortho chlorine substituents can bind to the constitutive androstane (CAR) (Denomme et al., 1983) and/or the pregnane X receptor (PXR) (Schuetz et al., 1998). Other ortho substituted PCB congeners interact with both the aryl hydrocarbon (Ah receptor) and the CAR receptor (Parkinson et al., 1983). PCB congeners with zero or one ortho-chlorine substituent can bind to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ah receptor), thus mimicking the action of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (Goldstein et al., 1978; Safe, 1994). These dioxin-like PCB congeners, for example PCBs 77 and 126, are of particular regulatory interest because of their mammalian and human toxicity, which appears to be mediated primarily via the Ah receptor.

Efforts to elucidate the molecular structure of individual PCB congeners are highly desirable because of the relationship between their three dimensional structure and their toxicity. Indeed, the crystal structures of several ortho substituted PCB congeners have been published (Kania-Korwel et al., 2004; Lehmler et al., 2001; Lehmler et al., 2005; Miao et al., 1997; Singh and McKinney, 1979; Singh et al., 1986; Vyas et al., 2006). However, despite the environmental importance of dioxin-like PCB congeners, no crystal structure of such a dioxin-like PCB congener has been reported to date. We herein report the first X-ray crystal structure of such a dioxin-like PCB congener, PCB 77 (3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl).

2. Results and discussion

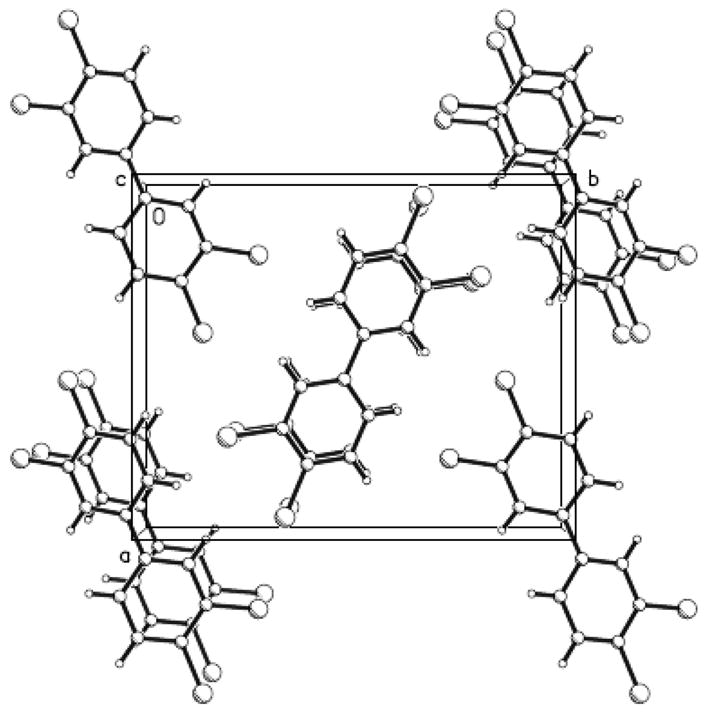

We were able to obtain crystals of PCB 77 suitable for crystal structure analysis by recrystallization from hot methanol. Crystal data and other relevant parameters are summarized in Table 1 and selected bond lengths and angles are given in Table 2. The molecular structure with the atom numbering scheme and a crystal packing diagram are shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, respectively. PCB 77 crystallizes in an orthorhombic space group (P21 21 2) with a = 11.1458(2) Å, b = 13.5539(3) Å, c = 3.7735(1) Å and α = β = γ; = 90°, with half a molecule per asymmetric unit. The closest Cl-Cl intermolecular interactions are 3.492(2) Å between Cl1 and a 2-fold screw related Cl2 (symmetry operation is x − 0.5, 0.5 − y, 1 − z).

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl.

| Empirical formula | C12 H6 Cl4 |

| Formula weight | 291.97 |

| Temperature | 120.0(2) K |

| Wavelength | 1.54178 Å |

| Crystal system, space group | Orthorhombic, P 21 21 2 |

| a = 11.1458(2) Å | |

| Unit cell dimensions | b = 13.5539(3) Å |

| c = 3.7735(1) Å | |

| Volume | 570.06(2) Å3 |

| Z, Calculated density | 2, 1.701 Mg/m3 |

| Absorption coefficient | 9.137 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 292 |

| Crystal size | 0.18 × 0.08 × 0.08 mm |

| Theta range for data collection | 5.14 to 67.49° |

| Limiting indices | −13 ≤ h ≤ 9, −15 ≤ k ≤ 16, −4 ≤ l ≤ 2 |

| Reflections collected/unique | 2102/852 [R(int) = 0.0298] |

| Completeness to θ = 67.49 | 96 % |

| Absorption correction | Semi-empirical from equivalents |

| Max. and min. transmission | 0.529 and 0.315 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 852/0/75 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.108 |

| Final R indices [I>2Σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0253, wR2 = 0.0652 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0254, wR2 = 0.0653 |

| Extinction coefficient | 0.0076(12) |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.301 and −0.280 eA−3 |

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl.

| C-atoms | Bond lengths [Å] | C-atoms | Bond angles [°] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cl(1)-C(3) | 1.733(2) | C(6)-C(1)-C(2) | 118.6(2) |

| Cl(2)-C(4) | 1.731(2) | C(6)-C(1)-C(1′) | 120.9(2) |

| C(1)-C(6) | 1.389(3) | C(2)-C(1)-C(1′) | 120.5(2) |

| C(1)-C(2) | 1.397(3) | C(3)-C(2)-C(1) | 120.4(2) |

| C(1)-C(1′) | 1.484(4) | C(3)-C(2)-H(2) | 119.8 |

| C(2)-C(3) | 1.380(3) | C(1)-C(2)-H(2) | 119.8 |

| C(2)-H(2) | 0.95 | C(2)-C(3)-C(4) | 120.6(2) |

| C(3)-C(4) | 1.387(4) | C(2)-C(3)-Cl(1) | 118.95(2) |

| C(4)-C(5) | 1.394(3) | C(4)-C(3)-Cl(1) | 120.49(2) |

| C(5)-C(6) | 1.383(4) | C(3)-C(4)-C(5) | 119.5(2) |

| C(5)-H(5) | 0.95 | C(3)-C(4)-Cl(2) | 121.29(2) |

| C(6)-H(6) | 0.95 | C(5)-C(4)-Cl(2) | 119.2(2) |

| C(6)-C(5)-C(4) | 119.6(2) | ||

| C(6)-C(5)-H(5) | 120.2 | ||

| C(4)-C(5)-H(5) | 120.2 | ||

| C(5)-C(6)-C(1) | 121.3(2) | ||

| C(5)-C(6)-H(6) | 119.4 | ||

| C(1)-C(6)-H(6) | 119.4 |

Symmetry transformations used to generate equivalent atoms: #1 −x+1,−y+1,z.

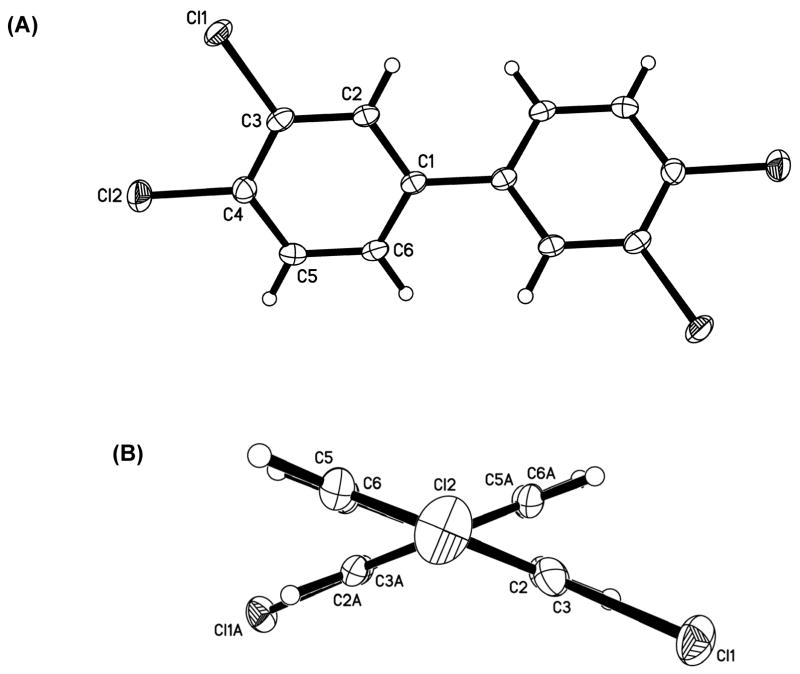

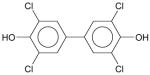

Figure 1.

(A) Molecular structure of PCB 77 showing the atom-labelling scheme and (B) view of PCB 77 along the C1-C1′ axis illustrating the non-planar conformation of the molecule. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Unlabeled atoms are at the symmetry position (1 − x; 1 − y; z).

Figure 2.

View of the crystal packing of 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachloro-biphenyl molecules parallel to the c-axis. Large circles are Cl atoms.

The dihedral angle between the two phenyl rings of PCB congeners is an important determinant to describe the conformation of PCBs, and, therefore, their binding activity with cellular target molecules (Lehmler et al., 2002; McKinney and Singh, 1988). The experimental dihedral angle for PCB 77 in the solid state is 43.94(6)° (Figure 1B). As shown in Table 3, this dihedral angle is larger than the dihedral angle of 3,3′,5′-trichloro-4-methoxybiphenyl (Lehmler et al., 2002) and of axially substituted biphenyls such as 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl (Brock et al., 1978). This value is also larger than the dihedral angles reported for biphenyl in different solvents (reported dihedral angels of biphenyl in solution range from approximately 30° to 40° depending on the solvent and the experimental approach used for its determination (Akiyama et al., 1986)) and the caldulated dihedral angle of 41.2°. However, the solid state dihedral angle of PCB 77 is smaller compared to experimental gas phase dihedral angles of biphenyl, 4-chlorobiphenyl and 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl, which are approximately 44-45° (Almenningen et al., 1985a and Almenningen et al., 1985b.

Table 3.

Comparison of the space group and solid state dihedral angle of selected chlorinated biphenyl derivatives without ortho substituent.

| Entry | Molecular structures of biphenyl | Space group | Solid state dihedral angle [°] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Orthorhombic, P 21 21 2 | 43.94(06) | present work |

| 2 |

|

Monoclinic, P21/c | 41.31 (07) | (Lehmler et al., 2002) |

| 3 |

|

Monoclinic, P21/n | 39.42 | (Brock et al., 1978) |

| 4 |

|

Monoclinic, P21/c | coplanar | (McKinney and Singh, 1988) |

To date 3,3′,5,5′-tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl is the only reported crystal structure of a non-ortho substituted PCB derivative (McKinney and Singh, 1988). This compound is a metabolite of PCB 77 (Doi et al., 2006; Koga et al., 1989) and has a strong affinity to both human estrogen sulfotransferase (Shevtsov et al., 2003) and thyroxine (McKinney et al., 1987). 3,3′,5,5′-tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl, like chlorinated dioxins (Boer and North, 1972; Boer et al., 1972; Cantrell et al., 1989; Cantrell et al., 1969; Koester et al., 1988), is essentially coplanar in the solid state, and thus adopts a conformation that is significantly different from that of PCB 77. The tendency of this dihydroxylated PCB derivative to adopt a more planar conformation in the solid state is due to the stabilizing intermolecular interactions resulting, in part, from a stacking arrangement of the benzene rings (McKinney and Singh, 1988). Although some stacking interactions are also present in PCB 77, the hypothetical energy gain resulting from the packing of coplanar PCB 77 molecules does not offset the increase in intramolecular energy associated with such a coplanar conformation. Therefore, in contrast to 3,3′,5,5′-tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl, PCB 77 does not adopt a coplanar conformation in its crystal structure.

The comparison of the solid state structure of PCB 77 and the structurally related 3,3′,5,5′-tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl shows that intermolecular interactions may be important determinants of the three-dimensional structure of PCBs. It has been proposed that similar intermolecular interactions are also important in the binding interactions of PCB congeners with target molecules such as the Ah receptor (Lehmler et al., 2002; McKinney and Singh, 1988). PCB molecules are likely to adopt a conformation that allows an energetically favourable binding to the target site due to the unrestricted rotation between two phenyl rings (i.e., the C1-C1′ bond). For example, crystallographic analysis of the binding of 3,3′,5,5′-tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl to human estrogen sulfotransferase shows the dihedral angle of the bound dihydroxy PCB was 30° (Shevtsov et al., 2003). For comparison, the solid state dihedral angle is significantly smaller at 0°, whereas the calculated dihedral angle is larger. This example suggests that the biologically relevant conformations of PCB congeners, such as PCB 77, and PCB metabolites, such as 3,3′,5,5′-tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl, exist over a range of dihedral angles, with the understanding that the dihedral angles may be greatly influenced by the protein-binding sites in which they were accommodated. Further studies are needed to determine the actual structure of PCB and other dioxin-like PCB congers in the binding site of their target molecules.

3. Conclusions

We herein report the crystal structure of PCB 77, a dioxin-like PCB congener. The dihedral angle between two phenyl rings of PCB 77 is 43.94(6)°, which is comparable to calculated or experimental dihedral angles of biphenyl and other PCB congeners in solution or in the gas phase. Overall, this X-ray crystallographic determination provides the first highly accurate picture of the molecular geometry of a dioxin-like PCB congener in a specific solid-state environment and gives some insight into the crystal packing arrangement which may help to understand the intermolecular forces of importance for the interaction of PCB 77 with biological binding sites.

4. Experimental

4.1. Synthesis of 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl (Shaikh et al., 2006)

3,3′,4,4′-tetrachloro-biphenyl was synthesized in 42% yield by copper bronze mediated symmetrical Ullmann coupling reaction (at 230 °C, 7 d) and purified by column chromatography over silica gel using a mixture of n-hexanes and ethyl acetate (10:1) as an eluent. Recrystallization from hot methanol was carried out to obtain the crystals suitable for X-ray analysis.

White solid. M.p. = 174–176 °C, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.36 (dd, J = 2.2 & J = 8.3 Hz, 2 × H-6), 7.51 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2 × H-5), 7.61 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 2 × H-2). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 126.15 (2 × C-6), 128.81 (2 × C-2), 130.97 (2 × C-5), 132.48 (2 × C-4), 133.25 (2 × C-3), 138.73 (2 × C-1). MS (EI): m/z (relative abundance %) 292 (M+, 100), 256 (M+-Cl, 5), 220 (M+-2Cl, 40), 184 (M+-3Cl, 10), 110 (12), 74 (5).

4.2. Molecular orbital computation of dihedral angle of PCB 77 with the SCF-MO method

The conformation of PCB 77 was calculated using semi-empirical SCF-MO calculations with an Austin Model 1 (AM1) Hamiltonian (Dewar et al., 1985). This was contained in the Spartan 02 package and carried out on a Quad 2.5 GHz Power Mac G5 with a PCI express graphic card as described previously (Luthe et al., 2007). The use of symmetry constraints enhanced the convergence compared with completely unconstrained runs. The calculated value of the dihedral angle of PCB 77 of 41.2° is the average of the four torsion angles involving C1-C1′.

4.3. X-ray crystal structure analysis

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 120.0(2) K on a Bruker-Nonius X8 Proteum diffractometer with graded-multilayer focusing optics from a rod-shaped crystal. Raw data were integrated, scaled, merged and corrected for Lorentz-polarization effects using the APEX2 package (Bruker-Nonius, 2004). The structure was solved by direct methods (Sheldrick, 1997) and missing atoms were located in difference Fourier maps (Sheldrick, 1997). Refinement was carried out against F2 by weighted full-matrix least-squares (Sheldrick, 1997). Hydrogen atoms were found in difference maps but subsequently placed at calculated positions and refined using a riding model. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. Atomic scattering factors were those of SHELXL (Sheldrick, 1997), as taken from the International Tables for Crystallography (Hahn, 1992). Crystal data and relevant details of the structure determinations are summarized in Table 1 and selected geometrical parameters are given in Table 2. Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this paper have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as Supplementary Publication No. CCDC-640770. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on application to the CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, U.K. (fax, (+44)1223-336- 033; e-mail, deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Acknowledgments

NSS and GL both thank the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Bonn, Germany) for a post-doctoral research fellowship. This research was supported by grant ES05605, ES012475 and ES013661 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH, and MRI grant #0319176 (SP) from the National Science Foundation. Contents of this manuscript are solely the reponsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NSF or Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akiyama M, Watanabe T, Kakihana M. Internal rotation of biphenyl in solution studied by IR and NMR spectra. J Phys Chem. 1986;90:1752–1755. [Google Scholar]

- Almenningen A, Bastiansen O, Fernholt L, Cyvin BN, Cyvin SJ, Samdal S. Structure and barrier of internal rotation of biphenyl derivatives in the gaseous state: Part 1 The molecular structure and normal coordinate analysis of normal biphenyl and perdeuterated biphenyl. J Mol Struct. 1985a;128:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Almenningen A, Bastlansen O, Gundersen S, Samdal S, Skancke A. Structure and barrier of internal rotation of biphenyl derivatives in the gaseous state: Part 3. Structure of 4-fluoro-, 4,4′-difluoro-, 4-chloro - and 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl. J Mol Struct. 1985b;128:95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Boer FP, North PP. Crystal and molecular structure of 2,7-dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Acta Cryst. 1972;B28:1613–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Boer FP, Van Remoortere FP, North PP, Neuman MA. Crystal and molecular structure of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Acta Cryst. 1972;B28:1023–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Brock CP, Kuo M-S, Levy HA. 4,4′-Dichlorobiphenyl: crystal packing in para-substituted biphenyls. Acta Cryst. 1978;B34:981–985. [Google Scholar]

- Bruker-Nonius. APEX2: Programs for data collection and reduction. Bruker-Nonius AXS; Madison, WI, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell JS, Beiter TA, Tomlin D. Structural analysis by diffraction of polychlorinated dioxins and dibenzofurans. Chemosphere. 1989;19:155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell JS, Webb NC, Mabis AJ. Identification and crystal structure of a hydropericardium-producing factor: 1,2,3,7,8,9-hexachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Acta Cryst. 1969;B25:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Denomme MA, Bandiera S, Lambert I, Copp L, Safe L, Safe S. Polychlorinated biphenyls as phenobarbitone-type inducers of microsomal enzymes. Structure-activity relationships for a series of 2,4-dichloro-substituted congeners. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:2955–2963. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar MJS, Zoebisch EG, Healy EF, Stewart JJP. Development and use of quantum mechanical molecular models. 76 AM1: a new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3902–3909. [Google Scholar]

- Doi AM, Lou Z, Holmes E, Venugopal CS, Nyagode B, James MO, Kleinow KM. Intestinal bioavailability and biotransformation of 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl (CB 77) in in situ preparations of channel catfish following dietary induction of CYP1A. Aquat Toxicol. 2006;77:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JA, Hass JR, Linko P, Harvan DJ. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzofuran in a commercially available 99% pure polychlorinated biphenyl isomer identified as the inducer of hepatic cytochrome P-448 and aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase in the rat. Drug Metab Dispos. 1978;6:258–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn T. Mathematical, Physical and Chemical Tables. C. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Holland: 1992. International Tables for Crystallography. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LG. The ortho side of PCBs: Occurrence and disposition. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kania-Korwel I, Parkin S, Robertson LW, Lehmler H-J. 2,4,5-Trichlorobiphenyl. Acta Cryst. 2004;E60:o1652–o1653. [Google Scholar]

- Koester CJ, Huffman JC, Hites RA. The crystal structure of octachlorodibenzodioxin: Experimental and calculated. Chemosphere. 1988;17:2419–2422. [Google Scholar]

- Koga N, Beppu M, Ishida C, Yoshimura H. Further studies on metabolism in vivo of 3,4,3′,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl in rats: identification of minor metabolites in rat feces. Xenobiotica. 1989;19:1307–1318. doi: 10.3109/00498258909043182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmler H-J, Parkin S, Robertson LW. 2,3,4′-Trichlorobiphenyl. Acta Cryst. 2001;E57:o111–o112. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmler HJ, Parkin S, Robertson LW. The three-dimensional structure of 3,3′,5′-trichloro-4-methoxybiphenyl, a “coplanar” polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) derivative. Chemosphere. 2002;46:485–488. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmler HJ, Robertson LW, Parkin S. 2,2′,3,3′,6-Pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 84) Acta Cryst. 2005;E61:o3025–o3026. [Google Scholar]

- Luthe G, Swenson DC, Robertson LW. Influence of fluoro-substitution on the planarity of 4-chlorobiphenyl (PCB 3) Acta Cryst B. 2007;63:319–327. doi: 10.1107/S0108768106054255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney J, Fannin R, Jordan S, Chae K, Rickenbacher U, Pedersen L. Polychlorinated biphenyls and related compound interactions with specific binding sites for thyroxine in rat liver nuclear extracts. J Med Chem. 1987;30:79–86. doi: 10.1021/jm00384a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney JD, Singh P. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetrachloro-4,4′-dihydroxybiphenyl. A Coplanar Polychlorinated Biphenyl in the Solid State. Acta Cryst. 1988;C44:558–562. [Google Scholar]

- Miao X, Chu S, Xu X, Jin X. Structure elucidation of polychlorinated biphenyls by X-ray analysis. Chin Sci Bull. 1997;42:1803–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson A, Safe SH, Robertson LW, Thomas PE, Ryan DE, Reik LM, Levin W. Immunochemical quantitation of cytochrome P-450 isozymes and epoxide hydrolase in liver microsomes from polychlorinated or polybrominated biphyenyl-treated rats. A study of structure-activity relationships. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5967–5976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson LW, Hansen LG. Recent advances in the environmental toxicology and health effects of PCBs. University Press of Kentucky; Lexington: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Safe SH. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1994;24:87–149. doi: 10.3109/10408449409049308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz EG, Brimer C, Schuetz JD. Environmental xenobiotics and the antihormones cyproterone acetate and spironolactone use the nuclear hormone pregnenolone X receptor to activate the CYP3A23 hormone response element. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:1113–1117. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh NS, Parkin S, Lehmler HJ. The Ullmann coupling reaction: A new approach to tetraarylstannanes. Organometallics. 2006;25:4207–4214. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM. SHELX97 - Programs for Crystal Structure Solution and Refinement. University of Gottingen; Germany: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shevtsov S, Petrotchenko EV, Pedersen LC, Negishi M. Crystallographic analysis of a hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyl (OH-PCB) bound to the catalytic estrogen binding site of human estrogen sulfotransferase. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:884–888. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, McKinney JD. 2,2′,4,4′,6,6′-hexachlorobiphenyl. Acta Cryst. 1979;B35:259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Pedersen LG, McKinney JD. Crystal and Energy-refined Structures of 2,2′,4,4′,5,5′-Hexachlorobiphenyl. Acta Cryst. 1986;C42:1172–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas SM, Parkin S, Lehmler HJ. 2,2′,3,4,4′,5,5′-Heptachlorobiphenyl (PCB 180) Acta Cryst. 2006;E E62:o2905–o2906. [Google Scholar]