SYNOPSIS

In 2002, the University of Minnesota School of Public Health (UMNSPH) adopted an approach that supports basic, advanced, and continuing education curricula to train current and future public health workers. This model for lifelong learning for public health practice education allows for the integration of competency domains from the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice's core public health workforce competency levels and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies.

This article describes how UMNSPH has implemented the model through coordination with state planning efforts and needs assessments in the tristate region of Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin. In addition, we discuss methods used for credentialing practitioners who have achieved competency at various levels of performance to enhance the capacity of the public health preparedness systems.

September 11, 2001, and the subsequent heightened pandemic alert, has created an environment in which the threat of disaster seems much less predictable, yet much more likely a possibility. In consequence, health-care and public health agencies have reviewed and expanded bioterrorism and emergency-readiness plans, and federal and state agencies have developed funding opportunities in support of these plans. All such plans, however, rely on the availability of sufficient numbers of health professionals prepared to recognize and respond to a wide variety of threats.

The one critical step in improving the nation's capacity for response is to improve the quality and delivery of education for all health professionals. Gaps in access to education and training have resulted in a reduced capacity of the public health and health-care systems to respond to urgent threats. New tools and methods to enhance learning opportunities for both on-campus and distant students, through the use of advanced technology, are needed for presentation and interaction with a variety of learners.

This article describes how the University of Minnesota School of Public Health (UMNSPH) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, has developed and implemented one such tool—a lifelong learning model for bioterrorism and emergency readiness, used for credentialing practitioners who have achieved competency at various levels of performance.

THE NEED FOR COMPETENCY-BASED CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

The process of curriculum development is being challenged as the demand to strengthen the public health workforce to respond to global and emerging threats moves to a competency framework.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Working Group on Competency-Based Curriculum of the Public Health Workforce Development Collaboration stated that a model is needed to help the learner move through a continuum where a person's goals for lifelong learning intersect with the organization's goals. The group also determined that competency models must be functional and include training and experience.2

A variety of methods exist both to attain or build competency, including academic degrees and continuing education, and to test and document competency, including self-assessment and certification. However, a framework incorporating these methods and strategies for bioterrorism and emergency readiness had not yet been implemented in service to public health when the demand for a prepared workforce intensified following 9/11.

The seeds for delivery of competency-based curricula in public health probably went much further back than the historic report, The Future of Public Health, by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 1988,3 but it was at this point that the public health communities of practice and academia began to build a sustainable bridge between theory and practice. At this same time, public health was entering a new era of partnerships, integrated delivery systems, and market-driven perspectives.4 These changing educational and economic environments, coupled with expanding restrictions on time and money, as well as limited access to quality education by many underserved and underrepresented populations, created considerable challenges in providing the necessary knowledge and skills to empower the public health workforce to meet the challenges of preparedness, response, and recovery from all hazards in the new century.

Several initiatives stemming from these early reports identified areas of competence required by individual public health disciplines. Two of the first commonly referenced documents were the Public Health Faculty/Agency Forum's final report5 and the U.S. Public Health Service's Public Health Workforce: An Agenda for the 21st Century,6 which discussed universal competencies expected of graduates from schools of public health as well as specific disciplines at the core of public health practice. Competency is a combination of knowledge elements (What do we need to know?), skills (What do we need to be able to do?), and attitudes or attributes (What values and beliefs motivate us and create commitment to action?) that enables public health practitioners to perform their work effectively and efficiently. These three elements are referred to as knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) and are the building blocks of competency statements. Critical to the understanding of competency are the notions that competency is related to a specific role or responsibility, that it is measured against established standards, and that acquisition of competency can be impacted by education and training.7

Evidence of the need for a coordinated system-wide team approach to assure public health training and education was noted in an initial report prepared by the Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH) Council of Public Health Practice Coordinators, entitled Demonstrating Excellence in Academic Public Health Practice. The report stated, “Multisector linkages are crucial to assuring that communities can effectively deliver services essential to the public's health.”8 Without partnerships, public health problems cannot effectively be solved in geographically dispersed service areas such as rural communities.

Subsequently the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice (COL),9 which comprises the leadership of academia and practice communities, was charged with determining innovative ways to incorporate practice principles into the curricula to meet the emerging challenges faced by this diverse interdisciplinary workforce. Core competencies and performance indicators have emerged in the last decade for a variety of specialty training,2 yet any curriculum useful for public health practitioners must be one that will foster collaborative and team efforts as well as teach key concepts.10 Since these initial efforts, ASPH has redefined the master of public health (MPH) specialty focus areas that make up the five core competencies of epidemiology, biostatistics, social and behavioral sciences, environmental health sciences, and health policy management, as well as cross-cutting interdisciplinary competencies for all public health workers.11

The national focus on preparedness after 9/11 highlighted the importance of having a sustainable system to assure a workforce competent to perform essential services and respond to public health threats and emergencies. In its 2003 report, Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century, the IOM defined a public health professional as “a person educated in public health or a related discipline who is employed to improve health through a population focus” and also recommended ensuring that public health workers demonstrate public health competencies appropriate to their jobs.12

Emerging threats require a new look at competency development. In its 2002 report, The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century, the IOM again examined the competence of the public health workforce, but this time as the responsibility of a multisector public health system in need of training and support. The report recommended measures to address public health issues and workforce demands, including new partnerships with several sectors such as the corporate community.13 The ability of public health professionals to work across these sectors led to the need to identify competencies and develop a model to bring the public health workforce along a continuum of learning that addressed these competencies. In addition, an equally important challenge existed in developing a competency framework along a career-progression pathway.

DEVELOPING A MODEL FOR LIFELONG LEARNING IN PUBLIC HEALTH PRACTICE EDUCATION

In keeping with the strategies proposed in the final report of the Public Health Faculty/Agency Forum5 and in the Public Health Service's Public Health Workforce: An Agenda for the 21st Century,6 UMNSPH adopted an approach in 2002 that supports basic, advanced, and continuing education curricula to train current and future public health workers in a set of competencies. This model for lifelong learning for public health practice education (Figure 1) allows for the integration of competency domains from the COL's core public health workforce competency levels9 and CDC's Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies.14 Implementation of the model is coordinated with state planning efforts and needs assessments in the tristate region of Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin. In addition, methods are used for credentialing practitioners who have achieved competency at various levels of performance.

Figure 1.

Model for lifelong learning for public health practice education, UMNSPH (Olson, 2002–2007)a

Olson DK. Evaluation of a model curriculum in bioterrorism and emergency readiness using gaming technology. Unpublished doctoral project. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2007.

Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs 1982;82:402-7.

Adapted from: Hoeppner M. Correlation of learning outcomes and competency. Report to Midwest Center for Life-Long-Learning in Public Health Executive Committee, January 2002. Minneapolis: Public Health Training Center Program, University of Minnesota School of Public Health; 2002. Grant No.: 5D20-HP00021 (D Olson, PI). Funded by Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services (US). Unpublished document.

Krathwohl DR. A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: an overview. Theory Into Practice 2002;41:212-8.

Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, Masia BB. Taxonomy of educational objectives: handbook II: affective domain. New York: David McKay Co., Inc.; 1964.

Simpson EJ. The classification of educational objectives in the psychomotor domain: the psychomotor domain, vol. 3. Washington: Gryphon House; 1972.

UMNSPH = University of Minnesota School of Public Health

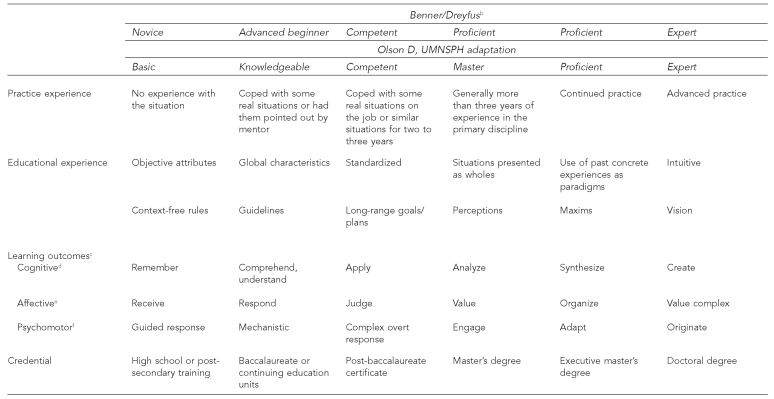

UMNSPH's lifelong-learning model builds on the theoretical base of two models used to address competency and development of skills in health systems. The Dreyfus model, as used by Benner, focuses on acquisition and development of skills with the premise that different levels reflect movement—from reliance on abstract concepts (novice), to use of past concrete experiences (expert); from seeing each situation as a single, unrelated event to understanding the whole situation as created by multiple, related events. Benner's work goes on to describe levels of expertise and identifies practice differences among five levels: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.15 Reflecting both the cultural and geographic diversity in which public health professions practice, Benner's model acknowledges the impact of context on developing and sustaining expertise. Her strong descriptors of the challenges of professional development at each level suggest methods to help educators assist and support progression of learners along the continuum.

Building on Benner's identification of levels of performance and movement of skill acquisition, UMNSPH's lifelong-learning model (Figure 1) adapts and enhances the Benner/Dreyfus model15 for use in an academic environment. Benner's model (novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, expert) was modified for the UMNSPH curriculum development project to better align with a philosophy of lifelong learning in public health as actualized in an academic environment. With this modification, for example, “novice” represented an individual on the pathway to awareness of public health as a career, such as a high school student; “knowledgeable” reflected someone at the stage of comprehension, such as would be expected at the level of an undergraduate; “competent” reflected application and long-range planning represented by post-baccalaureate certificate candidates; “master” reflected analysis and engagement represented by master's degree candidates with at least three years of experience in their primary discipline; “proficient” reflected a level of synthesis acquired through continued practice and education, qualifying the participant for an executive master's degree; and “expert” involved creation and origination represented by the doctorally trained and experienced professional.

As noted by Spross and Lawson,16 many authors who write about advanced practice cite Benner's model of expert practice.17 Spross and Lawson also stress the importance that Benner derived the model from the study of professionals who were experts by experience.16 Thus, experience and education are integral to the UMNSPH lifelong-learning model adapted from Benner's work.

Benner's work was tested as a continuum, based on nursing experience. Thus, the lifelong-learning model identifies the levels of situational experience in each part of the continuum to reflect the importance of experience in moving along the continuum. Educational experiences that would reinforce movement along the continuum are also identified. Learning outcomes provide a means for measurement of outcome in the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains at each stage of development (unpublished data, Correlation of Learning Outcomes and Competency, Report to Midwest Center for Life-Long-Learning in Public Health Executive Committee, Public Health Training Center Program, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, January 2002).

THE PROGRAM: A COMPETENCY-BASED CURRICULUM FOR PUBLIC HEALTH PREPAREDNESS, RESPONSE, AND RECOVERY

Academic health centers throughout the country initiated discussions as long ago as the late 1990s to explore the need for partnerships across educational units and within community organizations.8 As noted previously, a national response emerged from the COL,5 composed of leadership in academic and practice communities who were charged with determining innovative ways to incorporate practice principles into traditional curricula through distance-learning technology. The Schools of Public Health and Nursing at the University of Minnesota launched initiatives at that time to address the growing access gap in practice-based educational opportunities by bringing training to the workforce.

After 9/11, the question of workforce development received extensive coverage, and the concern for training of leaders in bioterrorism and emergency readiness was even more evident. To address these concerns, CDC, in collaboration with the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York City, developed core competencies in emergency preparedness for public health and health professional workers.10,14,18

At the same time, important initiatives were occurring at the federal level in funding of educational initiatives to address these competencies, bringing academicians, practitioners, and governmental partners together to enhance the capabilities of the health professional workforce to meet the challenges of new and emerging threats. One initiative was the CDC-funded network of Centers for Public Health Preparedness, seeking to ensure that frontline workers had skills and competencies required to effectively respond to current and emerging public health threats, including acts of bioterrorism. The notice of award for the University of Minnesota Center for Public Health Preparedness (UMNCPHP) was received in July 2002 (and renewed in 2004 through 2009), allowing for the development of a center with a primary target audience in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North Dakota.19

Another more recent initiative, the Minnesota Emergency Readiness Education and Training (MERET) program, funded through the Health Resources and Services Administration, was granted in 2005 through 2008 as a collaboration between the University of Minnesota Schools of Nursing and Public Health to provide a continuing education program to address education and training needs of the health-care workforce related to public health emergency or bioterrorism events.20 Both efforts—UMNCPHP and MERET—are built upon a process of needs assessment and curriculum development started in 2002 under the UMNCPHP funding. Contracts with the state of Minnesota in 2002 and Wisconsin in 2004 allowed for additional support for needs assessment on a state-specific basis. Statewide assessment for North Dakota was also performed under UMNCPHP funding in 2005, completing the identification of gaps in learning for all three states in the primary target area.

The following project description outlines the UMNCPHP competency needs assessment and development of the academic curriculum built in part to meet these needs. Results of the state-specific needs assessments identifying gaps in learning will not be discussed in this article, but have continued to inform the work of this project.

THE PROJECT

Needs assessment

One strategy in determining the need for a curriculum in bioterrorism and emergency readiness is to consult experts in the field in a modified Delphi process. In August 2002, a meeting was convened using a purposive sample of experts, including the directors of the state health alert network; staff from the office of emergency preparedness and bioterrorism education and training; local/regional bioterrorism coordinators; and community leaders from public health and health-care agencies representing food safety, epidemiology, occupational health, and tribal health in the state. The goals of the meeting were to (1) identify the potential audience for a curriculum in preparedness, response, and recovery; (2) generate ideas for courses and course content; and (3) identify what competencies students should gain by completion of the curriculum.

Group members were asked to identify what they thought they would need to know, need to be able to do, and need to value (KSAs) to protect the health of the community during events such as bioterrorism or other urgent threats. A modified Delphi technique was used with this group of experts. Delphi is characterized as a method for structuring a group communication process so that the process is effective in allowing a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem.

The structure used in this context involved the group members each developing a list of core content topics individually in response to the KSA questions. A discussion facilitator then posted all content topics for consideration and discussion by the entire group. A process facilitator recorded the content discussion. The group then generated additional content topics and added these topics to the list; other topics were combined by consensus. Following the meeting, the process facilitator reduced the list of topics to common units. As part of this review, the process facilitator made a determination about the relevance of the content topic to the audience for the course of study.

To support the reliability of the topic reduction by the process facilitator, the discussion facilitator reviewed the list separately. If the two reviewers did not agree, both reviewers discussed the unit topic and came to consensus as to the appropriate reduction of topic ideas. A second round of review by the group was solicited via e-mail, with the following topics of core content units agreed upon by the group members:

Disaster preparedness

Crisis/risk communication

Incident command management

Surveillance

Law

Impact on community health

Understanding agents

Additional review of the units of content was obtained from local public health directors in January 2003. This group was asked to look at the draft list of courses derived from the content units, to think about activities in their agencies, and to consider applicability of courses to their organizations. After the group had reviewed the materials, feedback from the discussion was given to course instructors for inclusion in the curriculum.

A review of the literature continued to inform curriculum development and the creation of professional training through the compilation of indicators of competency as further identification of need. Web searches of the phrases “emergency preparedness” and/or “bioterrorism” led to hundreds of potential data sources. To shape the initial search, the CDC website listing of biological and chemical agents of most concern was reviewed.21 These agents and the terms and titles of professional groups of interest were used as the starting point for the search conducted in the spring of 2003. Searches were limited to articles published after 1997 and articles published in English. Names of national experts in the field were also used for search purposes.

From this initial base, 105 topical searches were conducted. Additionally, searches were made of selected federal websites and national organizations such as the National Association of County and City Health Officials and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Disciplines of interest included the following: dentists, emergency-department physicians, emergency medical technicians (EMTs), epidemiologists, emergency-room/intensive-care-unit (ER/ICU) nurses, firefighters, health-care managers, health educators, infection-control practitioners, laboratory staff, medical examiners, paramedics, pharmacists, public health nurses, state and local public health administrators, urgent-care centers, and veterinarians.

Abstracts of articles were reviewed, and of those, the UMNCPHP evaluator and research assistants obtained and read 171 articles that discussed pertinent KSAs. Of these articles, the group documented 152 for final analysis and identified the main concepts and/or points of each article. As part of this initial review, the group made a determination regarding the relevance of the KSAs. The abstracts/main points were then reviewed, and a phrase representative of the KSA elements was created. As each article/abstract was reviewed, the group made a decision as to whether the existing phrases were representative of the KSA under consideration. If not, a new phrase was created and added to the list. To support the reliability of the coding, a second member of the team reviewed every 10th abstract and affirmed the codes. If there was not agreement on the initial coding, both reviewers discussed the codes and came to consensus as to the appropriate code for the abstract in question.

As each abstract was coded, the evaluator and assistants also determined which of the professional groups were the target of the article or referenced therein. From this process, they created lists of KSAs for specific groups of professionals. The inventories for each professional group were presented first as a discipline-specific listing, followed by a grid presenting KSAs across all disciplines for ease of comparison. The staff ended the literature search when they identified that the articles being found were not resulting in new concepts.

While some codes appeared in the literature infrequently or were targeted to only one or two professional groups, many KSAs were seen as common to many groups of public health professionals or emergency responders. For more than 75% of the 17 professional groups around which the literature review was structured, the following KSAs were identified:

Collaborative skills

Communication skills

Coordination across agencies

Correct use of personal protective equipment

Diagnosis of disease related to agents of concern

Disease-reporting protocols

Incident command system

Information system management related to surveillance

Isolation procedures

Medical management of victims

Prophylaxis

Triage/triage categories

These KSAs reflect activities that span all phases of a terrorist, infectious-disease, or other urgent event. Additionally, historical events and full-scale drills have brought into sharp focus the different cultures, norms, and working processes of the emergency services and public health communities. The literature reflects the need for both of these systems to collaborate in ways that recognize the expertise and strengths of both. The literature also speaks to the need for acute-care health professionals to develop bioterrorism/emergency-preparedness KSAs to support management of large numbers of victims; for hospitals to be able to implement disaster protocols rapidly and in a comprehensive manner; and for ambulatory-care clinics to develop systems to support surveillance as well as assist in the care of victims.

The identification of KSAs critical to curriculum development was inextricably linked to the identification of learning needs of public health professionals in state and local agencies, and the development of preparedness and response infrastructure. Beginning in 2003, assistance with identification of learning needs for the public health workforce was requested from regional and state departments of health. Building on the recently completed literature review and analysis, additional steps were taken to identify important competency elements.

Six focus groups and multiple key informant interviews were conducted over a seven-week period in 2003 to obtain feedback on the knowledge and skill elements, and to add any elements viewed critical by practitioners that had not emerged from the literature review process. Focus groups comprised state and local public health professionals working in the areas of epidemiology, administration/management, nursing, environmental health, safety, laboratory services, hospital preparedness, health education, and planning. Key informants included professionals from nursing and medical professional associations, and veterinary-science faculty. Three emergency-medicine physicians involved with level-one trauma centers were interviewed, as was one director of safety and emergency preparedness in a metropolitan area. In all, nearly 100 public health and acute-care professionals participated in the focus groups and/or interviews.

This process, in combination with the literature review, led to the generation of a list of 636 potential competency indicators. Constant comparative methods22–24 were used to reduce the data to a list of 272 KSAs. This list of KSAs was correlated to the CDC Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies.14 Of the potential KSAs, 132 were selected as best reflective of desired cross-cutting and role-specific competencies. These indicators were grouped as follows:

Cross-cutting indicators of competency

Training

Communications/media relations

Planning

Response/mitigation

Recovery

Direct patient care

Inter-/intra-organizational relations

Surveillance/epidemiology

Laboratory science/pathology

These groupings and the associated indicators were sent out to key informants in state and local agencies, and to emergency medical services for feedback. As a result of their comments, one additional grouping was created: cultural responsiveness. Indicators were re-sorted to integrate this new grouping. Of the 132 indicators, 14 indicators were deleted, and one additional indicator that was identified through consensus was added. The result was a list of 119 KSA elements that could be used to assess learning needs.

Following approval by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, people working in state and local public health agencies were invited to participate in a survey (Minnesota in 2003, Wisconsin in 2005, and North Dakota in 2006). Thirteen role-specific versions of the surveys (both paper and electronic formats) were created using various combinations of the 119 indicators. At the request of some of the states, samples of ER/ICU nurses, paramedics/EMTs, physicians, infectious-disease physicians and nurses, certified industrial hygienists, hospital laboratory staff, veterinarians, health educators in community-based agencies, and ambulatory-care managers and nurses were also invited to complete surveys. Those completing the surveys were asked to self-identify their level of confidence in their ability to perform a specific knowledge or skill, and to rate the importance of that indicator for them to know or be able to do. A total of 5,256 surveys were returned for analysis (2,663 from Minnesota; 2,382 from Wisconsin; and 211 from North Dakota).

Analysis of the KSA indicators used to develop the survey tools has revealed that these represent useful elements around which to assess learning needs and build curriculum efforts. For those responding who were employed in state public health agencies, 88.5% of the indicators were rated by the majority of the responders as “very important” or “important” for them to know or be able to perform (range across three states: 85.3% to 92.2%). For those working either at the local level in public health or working in the community or in acute-care settings, 97.2% of the indicators were rated by the majority of responders as “very important” or “important” for them to know or be able to perform (range across three states: 94.8% to 100.0%). Results of the learning needs assessments have been used on an ongoing basis to help inform education and training efforts as well as the curriculum development process.

Learning opportunities

According to DePalma and McGuire, “Primary goals for any specific role can be broadly guided by standards and competencies that have been developed and distributed by professional organizations or accrediting and licensing agencies.”25

In its Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies report, CDC and the Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy write, “Because emergency response works best using a consistent system that is varied only slightly to accommodate the specific needs of each emergency… BT [bioterrorism and emergency-readiness] competencies, with minor editing, must apply to [all] categories of emergency, including those that relate to chemical, nuclear, or explosive devices. The specific application of any competency is always within the context of both agency and jurisdiction plans.”14

As both of these quotes affirm, the process of curriculum development to strengthen the public health workforce to respond to global challenges and emerging threats must apply across all hazards and reinforce an interprofessional plan of action. Competencies can be acquired through experience, performance support systems, and on-the-job training—not just through formal educational activities. While all public health workforce development has been charged to be competency-based, there is no expectation for a single, uniform curriculum for bioterrorism and emergency readiness. Competency statements do not make a distinction between academic- and practice-acquired knowledge and skills, and thus will link theory/research (academic) with the execution of work (practice). However, because competency can only be demonstrated through action, the KSAs identified in the literature for each discipline can only be used as indicators of competency. True measurement of competency is evaluated through observation of performance.

Public health competencies may be developed in multiple ways, but all are expected to be mapped to at least one of two foundation documents: the 1988 IOM report on The Future of Public Health3 or the COL's Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals.5,9 In 2001, the COL was committed to assisting the U.S. Public Health Service in efforts to implement components of the Public Health Workforce: Agenda for the 21st Century report pertaining to public health competencies that were reviewed earlier by the Public Health Faculty/Agency Forum.5 The COL thus developed a list of approximately 68 core competencies for public health professionals. The core competencies represent the set of KSAs necessary for the broad practice of public health, and go beyond the boundaries of the specific disciplines within public health, unifying the profession. The competencies are divided into eight domains:

Analytic assessment skills

Basic public health science skills

Cultural competency skills

Communication

Community dimensions of practice

Financial planning and management

Leadership and systems thinking

Policy development and program planning skills

For ease of use in defining areas of core competence in developing the UMNSPH curriculum in public health practice, the following structure was adopted combining the eight domains of the COL into four areas of need:

Public policy development using a systems framework

Interventions based on the dimensions of community and culture

Assessment and application of basic public health sciences

Program management and communications principles

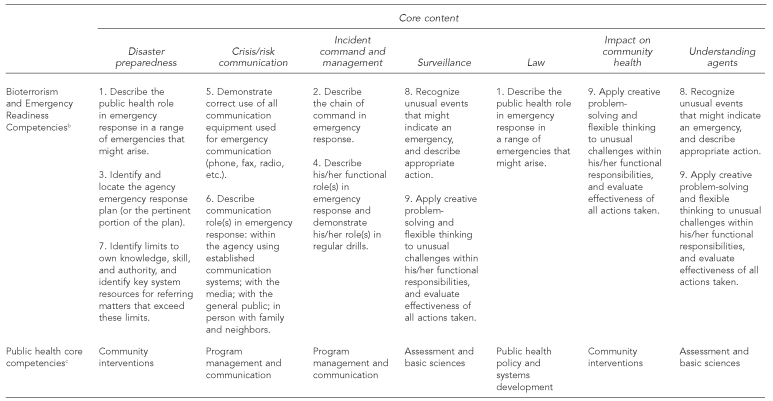

These domains then formed the foundation upon which the special KSAs for bioterrorism and emergency readiness could be framed. The curriculum in bioterrorism and emergency readiness (Figure 2) was created as a special focus of study within public health practice, permitting public health and other professionals in the fields of health and human services to attain the KSAs (competencies) to protect the health of the community. Students take a minimum of a 12-credit curriculum, with a four-year time limit for completion.

Figure 2.

Bioterrorism and emergency readiness curriculum plan, University of Minnesota School of Public Health (Olson, 2002–2007)a

Olson DK. Evaluation of a model curriculum in bioterrorism and emergency readiness using gaming technology. Unpublished doctoral project. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2007.

Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Bioterrorism and emergency readiness: competencies for all public health workers. New York: Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy; 2002.

Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. Core competencies for public health professionals [cited 2003 Apr 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.trainingfinder.org/competencies/list_levels.htm

The competencies (or outcomes) coincide with CDC's Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies14 with a “cross walk” to the foundational competencies of public health identified by the COL9 and verified by core content identified in the curriculum planning committee and community focus groups. Figure 2 illustrates the connection between content and competency. These competencies are then acquired through a selection of courses that meet each of the seven content areas. Course faculty create learning objectives for each course based on competency indicators identified through the needs assessment.

One challenge is the lack of a consistent understanding of what learning objectives are and how to create them for outcome measurement. To help with faculty development in this area, UMNCPHP created a learning-outcome and competency-leveling process that provides a guide for the faculty. Faculty have been encouraged to use the guide to create their courses and to map their courses to competencies19 for inclusion in the learning management system.

Evaluation of learning outcomes

More than 193 students in MPH and public health certificate programs—including preparedness, response and recovery, and food safety/biosecurity—have been admitted into the 12-credit bioterrorism and emergency-readiness curriculum since 2002 at UMNSPH. Evaluation of the level of integration and application of preparedness principles by these health professionals is needed to demonstrate competency. The question is, “Does education make a difference in the ability of health professionals to respond in times of disaster?” This question reflects the same concerns that many other professionals nationwide have expressed. Academics and trainers alike are searching for the answer.

Evaluative research seeks to assess processes and outcomes of the program applied to a problem or the outcome of prevailing practices.26 One model that furthers the concept of evaluative research to educational problems was developed by D.L. Kirkpatrick, who identified four levels of evaluation: reaction, learning, behavior, and results.27 UMNSPH incorporated these four levels of evaluation for the courses in preparedness, response, and recovery via course evaluations and six- and 12-month follow-up studies sponsored through UMNCPHP. UMNCPHP has provided logistical infrastructure and support for the delivery of 67 public health-preparedness academic courses reaching 1,680 participants for a total of 28,547 hours of training. This includes 294 scholarships and tuition waivers awarded to assist learners. These participants reported that, as a result of their training, they had reached more than 729,000 fellow public health workers and citizens. Testimonials of the impact of the training offered have included the following comments:

I am currently the Education, Exercises and Planning supervisor at the Minnesota Department of Health, Office of Emergency Preparedness.… I thank the University [Center for Public Health Preparedness] for blazing the trail in meeting the distinctive needs of the current preparedness workforce. I believe I would not be in the position I am today if I had not had the opportunity to advance my knowledge in their uniquely structured program.

I have reviewed and updated our plans [for crisis response]. I have trained staff on the topics I studied. These courses have made me understand what other training I need as well as [training needed by] other staff and partners in preparedness. We have addressed mental health needs more in our planning and training.

It has helped me in everything I do related to emergency preparedness! [The training] gave me more knowledge about writing plans… about designing plan exercises… about working with the media and developing a media kit… about discussing mental health issues with local providers… about planning for emergencies with community leaders.

In 2007, further evaluation using a hybrid Kirkpatrick model to evaluate the curriculum as a whole was incorporated. This was done by employing a gaming simulation called “Disaster in Franklin County,” which provides a performance-based experiential testing environment that allows health professional workers to put theory into practice—from awareness of an urgent threat to analysis and decision-making of what to do given the threat level. This online simulation follows the response of public health workers to a natural disaster striking the fictional community of Franklin County. Players assist the public health director, environmental health specialist, public health nurse, and other public health workers in applying their emergency response and recovery skills to minimize the impact on the community. This interprofessional approach allows for greater flexibility in testing the integration of concepts and the decision-making ability of the player.

The gaming simulation is used as an experiential test for the students who have participated in the bioterrorism and emergency-readiness curriculum. “Disaster in Franklin County” provides an opportunity to immerse the student/graduate in the subject while demonstrating they have integrated the KSAs (competencies) necessary to make timely and effective decisions, and respond appropriately given the threat level. Through an experiential testing of the curriculum in combination with evaluation of course-specific levels of impact, it is hoped that we will be better able to answer the question: “Does education make a difference?”

CONCLUSION

One of the most difficult challenges facing public health agencies in their attempt to develop their capacity to respond to public health threats and emergencies is assuring a qualified workforce available to carry out these functions, as noted in CDC's 2006 report, Advancing the Nation's Health: A Guide to Public Health Research Needs:

Vital to maximizing current and future public health impact is an educated, knowledgeable workforce operating in a model public health system. A health workforce that is effective and efficient, diverse, well-educated, and committed to reaching persons at highest risk for disease, injury, and disability is key to the success of any public health effort.28

Recruitment, retention, and training of the next generation of public health professionals are challenges that require innovation and action. In the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials' enumeration study, 14 of the 37 states reporting workforce shortages were considering incentives designed to advance competencies of their public health workforce, including professional training and distance-learning opportunities. The report notes, “The challenges of our increasingly complex and interdependent world require new approaches to generating and disseminating the knowledge and innovations needed to promote well-being and improve health.”29 One method to meet these challenges is through innovation in digital and lifelong learning, incorporated in a model, core curriculum for bioterrorism and emergency readiness.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corso LC, Wiesner PJ, Halverson PK, Brown CK. Using the essential services as a foundation for performance measurement and assessment of local public health systems. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2000;6:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200006050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Workforce Policy and Planning, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) [cited 2003 Apr 29];Competencies for public health workers: a collection of competency sets of public health-related occupations and professions. 2001 Available from: URL: http://www.phppo.cdc.gov/workforce [archived 2007 Feb 13]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The future of public health. Washington: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerzoff RB, Brown CK, Baker EL. Full-time employees of U.S. local health departments, 1992–1993. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1999;5:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorensen AA, Bialek RG, editors. The public health faculty/agency forum: linking graduate education and practice—final report. Gainesville (FL): University Press of Florida; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service (US) [cited 2003 Apr 29];The public health workforce: an agenda for the 21st century. A report of the Public Health Functions Project. Available from: URL: http://web.health.gov/phfunctions.

- 7.Lucia AD, Lepsinger R. The art and science of competency models: pinpointing critical success factors in organizations. San Francisco: Pfeiffer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of Schools of Public Health Council of Public Health Practice Coordinators. Demonstrating excellence in academic public health practice. Washington: ASPH; 1999. p. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. [cited 2003 Apr 29];Core competencies for public health professionals. Available from: URL: http://www.trainingfinder.org/competencies/list_levels.htm.

- 10.Gebbie K, Merrill J. Public health worker competencies for emergency response. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2002;8:73–81. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of Schools of Public Health, ASPH Education Committee. Master's degree in public health core competency development project, version 2.3. Washington: ASPH; 2006. [cited 2008 Feb 25]. Also available from: URL: http://www.asph.org/userfiles/version2.3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebbie KM, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Institute of Medicine. Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. Who will keep the public healthy? [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Bioterrorism and emergency readiness: competencies for all public health workers. New York: Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82:402–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spross JA, Lawson MT. Conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing. In: Hamric AB, Spross JA, Hanson CM, editors. Advanced practice nursing: an integrative approach. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier/W.B. Saunders Co.; 2005. pp. 47–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benner P. From novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park (CA): Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gebbie KM, Hwang I. Preparing currently employed public health professionals for changes in the health system. New York: Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson D, Hedberg C. University of Minnesota Center for Public Health Preparedness. Prepare, respond, recover. [cited 2008 Feb 29];Funded by the ASPH/CDC/ATSDR Cooperative Agreement A1004-21/21. Available from: URL: http://cpheo.sph.umn.edu/umncphp.

- 20.O'Boyle C, Olson D. Minnesota emergency readiness education and training. [cited 2008 Feb 29];Funded by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, DHHS, Bioterrorism Training and Curriculum Development Program. #T01HP006412 Available from: URL: http://cpheo.sph.umn.edu/meret.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) [cited 2008 Feb 29];Bioterrorism agents/diseases. Available from: URL: http://www.emergency.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist.asp.

- 22.Wolcott H. Writing up qualitative research. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guba E, Lincoln Y. Effective evaluation: improving the usefulness of evaluation results through responsive and naturalistic approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogdan R, Biklen S. 2nd ed. Needham Heights (MA): Allyn and Bacon; 1992. Qualitative research in education: an introduction to theory and methods. [Google Scholar]

- 25.DePalma JA, McGuire DB. Research. In: Hamric AB, Spross JA, Hanson CM, editors. Advanced practice nursing: an integrative approach. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier/W.B. Saunders Co.; 2005. pp. 257–300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suchman E. Evaluative research: principles and practice in public service and social action programs. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) [cited 2007 Nov 18];Advancing the nation's health: a guide to public health research needs, 2006–2015. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/od/science/PHResearch/cdcra/AdvancingTheNationsHealth.pdf.

- 29.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. [cited 2007 Nov 17];State public health employee worker shortage report: a civil service recruitment and retention crisis. Available from: URL: httop://www.astho.org/pubs/Workforce-Survey-Report-2.pdf.