Abstract

Aldose reductase (AR) catalyzes the reduction of several aldehydes ranging from lipid peroxidation products to glucose. The activity of AR is increased in the ischemic heart due to oxidation of its cysteine residues, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. To examine signaling mechanisms regulating AR activation, we studied the role of nitric oxide (NO). Treatment with the NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor, N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester prevented ischemia-induced AR activation and myocardial sorbitol accumulation in rat hearts subjected to global ischemia ex vivo or coronary ligation in situ, whereas inhibition of inducible NOS and neuronal NOS had no effect. Activation of AR in the ischemic heart was abolished by pretreatment with peroxynitrite scavengers hesperetin or 5, 10, 15, 20-tetrakis-[4-sulfonatophenyl]-porphyrinato-iron [III]. Site-directed mutagenesis and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analyses showed that Cys-298 of AR was readily oxidized to sulfenic acid by peroxynitrite. Treatment with bradykinin and insulin led to a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent increase in the phosphorylation of endothelial NOS at Ser-1177 and, even in the absence of ischemia, was sufficient in activating AR. Activation of AR by bradykinin and insulin was reversed upon reduction with dithiothreitol or by inhibiting NOS or PI3K. Treatment with AR inhibitors sorbinil or tolrestat reduced post-ischemic recovery in the rat hearts subjected to global ischemia and increased the infarct size when given before ischemia or upon reperfusion. These results suggest that AR is a cardioprotective protein and that its activation in the ischemic heart is due to peroxynitrite-mediated oxidation of Cys-298 to sulfenic acid via the PI3K/Akt/endothelial NOS pathway.

Aldose reductase (AR2; EC 1.1.1.21) is a member of the aldoketo reductase (AKR) superfamily (AKR1B1). It catalyzes the reduction of a broad spectrum of substrates that range from simple aromatic aldehydes and steroid carbonyls to aldo-keto sugars (1, 2). The wide substrate specificity of AR suggests that the enzyme may be involved in detoxification of endogenous and xenobiotic aldehydes. Our studies show that AR displays highest catalytic efficiency with aldehydes derived from phospholipid oxidation (3). Both free aldehydes, such as 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal, and phospholipid-bound aldehydes, such as 1-palmitoyl-2-oxo-valeroyl-phosphatidylcholine, are high affinity substrates of the enzyme (4, 5). In addition, AR is also capable of catalyzing the reduction of glutathione conjugates of unsaturated aldehydes (6, 7). In case of short-chain aldehydes such as acrolein or crotonaldehyde, catalytic efficiency of AR is severalfold higher with the glutathione conjugate than with the parent aldehyde (7). Consistent with its antioxidant role, AR is up-regulated under conditions of oxidative stress (2), such as vascular inflammation (8), heart failure (9), and ischemic preconditioning in rabbit (10) and rat (11) hearts. Nevertheless, the functional significance of AR up-regulation under conditions of oxidative stress remains unclear. Extant data are contradictory. Although some studies show that inhibition of AR increases peroxide and aldehyde toxicity (12) and inflammation-induced vascular cell death (8), other investigators have reported that inhibition of the enzyme could protect the heart against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury (13–15) as well as the development of secondary diabetic complications (2). It has also been reported that overexpression of AR increases atherogenesis in apoE-null mice (16).

We have recently reported that AR is activated in the heart by reactive oxygen species (17) generated during ischemia and reperfusion (18, 19). Activation of AR in the ischemic heart was found to be due to oxidation of its cysteine residues to sulfenic acids (17). Nonetheless, it remained unclear whether oxidation of AR cysteines to sulfenic acid is a spurious occurrence due to the highly oxidizing conditions prevalent in the ischemic heart or whether it is a controlled event of post-translational modification regulated by intracellular signaling. Accordingly, the present study was undertaken to examine the role of nitric oxide (NO) in this process. Our previous studies show that NO regulates AR activity in vitro (20–22) and in vivo (23, 24). Our primary hypothesis was that NO activates AR in the ischemic hearts and that the activated AR, in turn, protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Our findings support this hypothesis and suggest that activation of AR in the ischemic heart is a highly regulated process that could be attributed to peroxynitrite generated in response to stimulation of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Preliminary findings of this study have been reported previously (25).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Ammonium acetate, d,l-glyceraldehyde, dimedone, dithiothreitol (DTT), hesperetin, insulin, heparin, triethanolamine, Me2SO, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002), mammalian protease inhibitor mixture, N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-aminoethyl)-(aminopentyl)]-N′-nitroguanidine (AAEAPNG), bradykinin, sorbitol, sorbitol dehydrogenase, and peroxynitrite were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The peroxynitrite scavenger, FeTPPS (5,10,15,20-tetrakis-[4-sulfonatophenyl]-porphyrinato iron [III]) was purchased from Calbiochem. Sorbinil (d6-fluoro-spiro-(chroman-4,4′-(imidazolidine)-2′,5′-dione) and the inducible NOS inhibitor BBS-2 (pyrimidine imidazole, or clotrimazole) were the gifts from Pfizer. Tolrestat (N-methyl-N-[(5-trifluoromethyl-6-methoxy-1-napthalenyl)-thiomethyl] glycine was a gift from American Home Products. Primary polyclonal anti-eNOS and phospho-eNOS (Ser(P)-1177)-specific antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Sephadex G-25 columns, enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus) reagents, and horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies were obtained from Amersham Biosciences. All other reagents were of analytical grade. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Harland Teklad.

Global Ischemia-Reperfusion ex Vivo—A total of 296 rats were used for the entire study. For global ischemia, hearts excised from male rats (300–350 g, 12–16 weeks of age) were cannulated and perfused in the Langendorff retrograde mode, as described (3, 26). Briefly, the hearts were perfused at a constant perfusion pressure of 80 mm Hg with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) solution, pH 7.4, containing 118 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 3 mm CaCl2, 1.25 mm MgCl2, 25 mm NaHCO3, 1.25 mm KH2PO4, 0.5 mm EDTA, 10 mm glucose and equilibrated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 for 10 min. A latex fluid-filled balloon was placed in the left ventricle through an incision in the left atrial appendage and inflated to a pressure of 8–10 mm Hg. The perfusion flow rate was between 8 and 12 ml/min for all heart preparations. The hearts were either perfused for 40 or 70 min with KH solution under aerobic conditions or subjected to indicated durations of ischemia alone or ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion. Drugs were added to the KH solution 10 min before ischemia. At the end of the protocol, the hearts were freeze-clamped and used for measuring AR and sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) activity, sorbitol content, and for Western blot analysis.

In Situ Model of Myocardial Infarction—Male rats (250 to 300 g, 9–12 weeks of age) were subjected either to 20 or 30 min of coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion or to 15–30 min of occlusion followed by 30 min of reperfusion as described before (17, 27). For studying the effect of AR inhibitors on myocardial ischemic injury, rats were assigned to 6 different groups; in groups 1 and 3, the rats were treated with vehicle (Me2SO, intraperitoneal) alone 30 min before occlusion and subjected to either 20 or 30 min of coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion. Groups 2 and 4 rats received sorbinil (40 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) 30 min before occlusion and underwent either 20 or 30 min of coronary artery occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion. Group 5 rats were subjected to 30 min of coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion and received intravenous injection of a vehicle (Me2SO) 5 min before reperfusion. Group 6 rats were subjected to 30 min of coronary artery occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion and received intravenous injection of sorbinil (40 mg/kg) 5 min before reperfusion. Rats were given heparin (200 units, intravenously) and then were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intravenous). The hearts were excised and perfused with KH solution through an aortic cannula using the Langendorff apparatus. To delineate the infarcted from the viable myocardium, the hearts were then perfused with a 1% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC staining) in KH solution at a pressure of ∼60 mm Hg (10 ml over 5 min). To demarcate the occluded-reperfused coronary vascular bed, the coronary artery was tied at the site of the previous occlusion, and the aortic root was perfused with a 5% solution of phthalo blue dye (Heucotech, Fairless Hill, PA) in normal saline (3 ml over 3 min). The portion of the left ventricle (LV) supplied by the previously occluded coronary artery (area at risk) was identified by the absence of a blue dye, whereas the rest of the LV was stained dark blue. The heart was then cut into 6–7 transverse slices, and all atrial and right ventricular tissues were excised. The slices were weighed, fixed in a 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution, and photographed (Nikon D100 digital camera with a Nikon AF28–105-mm lens plus Promaster Spectrum 7 close-up lenses). Color pictures of heart slices were projected onto a paper screen at 10× magnification, and the borders of the infarcted and ischemic-reperfused and non-ischemic regions were traced. The traced papers were then scanned into the computer, and corresponding areas were measured by computerized planimetry (Adobe Photoshop, Version 7.0). The infarct size was calculated as a percentage of the area at risk.

Measurement of AR Activity and Sorbitol Content—The catalytic activity of AR and tissue sorbitol content were measured as described previously (17). Briefly, left ventricular tissue was homogenized in 10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, containing 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT and protease inhibitor mixture (1:100, v/v). Where indicated, the enzyme was reduced with 100 mm DTT for 1 h at 37 °C in 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0. AR activity was measured in 100 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, containing 0.15 mm NADPH and 10 mm glyceraldehyde.

Modification of Recombinant AR—Human recombinant AR:WT, AR:C298S, and AR:C303S mutants were purified from Escherichia coli as described earlier (28) except that a His-tag leader sequence was inserted into cDNA. The proteins were purified on a Ni2+ affinity column as described before (17). To examine the molecular mechanism of peroxynitrite-mediated AR activation, reduced DTT-free enzyme (0.3 mg) was incubated with 0.01–1 mm peroxynitrite for 1 h in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, in the dark. The reaction was stopped by desalting the enzyme on Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, or 10 mm ammonium acetate, pH 7.0. To document sulfenic acid formation, the modified protein was incubated for 30 min with 0.5 mm dimedone, a sulfenic-acid specific reagent.

Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI/MS)—For ESI/MS analysis the protein was desalted on a Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with N2-saturated ammonium acetate (10 mm, pH 7.0). The desalted protein was diluted with the flow injection solvent (acetonitrile:H2O:formic acid; 50:50:1, v/v/v). The mixture was injected into a MicroMass ZMD spectrometer at a rate of 10 μl/min. The operating parameters were as follows: capillary voltage 3.1 kV; cone voltage 27 V; extractor voltage 4 V; source block temperature 100 °C and desolvation temperature 200 °C. Spectra were acquired at the rate of 200 atomic mass units over the range of 20–2000 atomic mass units. The instrument was calibrated with myoglobin (0.15 mg/ml) dissolved in the mixture of acetonitrile and H2O 50:50 (v/v) containing 0.2% (v/v) formic acid.

Western Blot Analysis—Heart tissue was homogenized in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, containing 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 10 mm NaF, 10 mm Na3VO4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (1:100). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a polyvinyl difluoride membrane. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with the ECL Plus Western blot detection kit.

Measurement of SDH Activity—The activity of SDH was determined by spectrophotometric monitoring of NADH oxidation, when fructose was reduced to sorbitol, as described previously (29). Briefly, rat hearts and liver tissues were homogenized in 100 mm triethanolamine, pH 7.4, on ice. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the resulting supernatant was used for enzymatic assay under 100 mm triethanolamine, pH 7.4, 0.4 m fructose, and 0.4 mm NADH. The decrease in A340 was monitored for 3 min at room temperature.

Statistical Analysis—Individual saturation curves used to obtain steady-state kinetic parameters were analyzed using a general Michaelis-Menten equation in EnzFitter (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK). In all cases best fits to the data were chosen on the basis of the standard error of the fitted parameters. All data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. and were analyzed by one way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons or by Student's t test for unpaired data. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

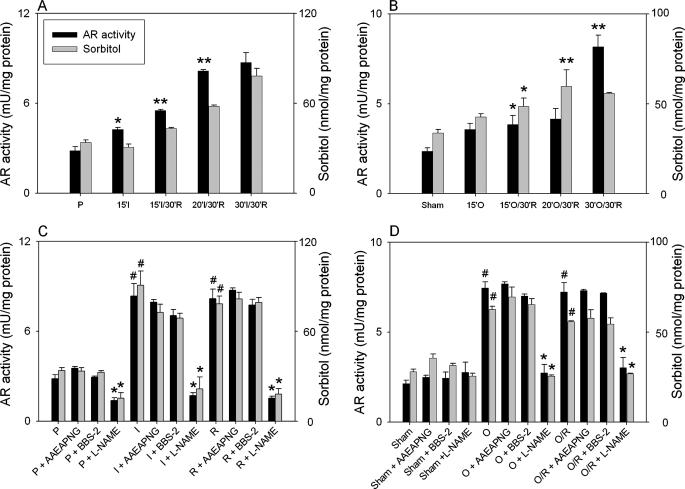

AR Activation Is Mediated by NO—Our previous study shows that the activity of AR is increased in rat hearts subjected to ischemia (17). Because NO production is increased in the ischemic heart (30) and AR is activated by NO (13), we examined the role of NO using NOS inhibitors. As reported before (17), measurements of AR activity and sorbitol levels in the heart tissue after different durations of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion showed a time-dependent increase that reached a maxima after 30 min of ischemia in both ex vivo (Fig. 1A) and in situ (Fig. 1B) models. To examine whether NO generation in the ischemic myocardium affects AR activation, hearts were treated with NOS inhibitor l-NAME before initiating ischemia. As shown in Fig. 1C, treatment with l-NAME (0.1 mm) led to a slight but statistically significant decrease in AR activity and sorbitol content in the perfused hearts and completely prevented AR activation in both ex vivo (Fig. 1C) and in situ (Fig. 1D) models of ischemia-reperfusion. To examine the role of specific NOS isoforms, hearts were treated with the neuronal NOS inhibitor AAEAPNG or the inducible NOS inhibitor BBS-2. As shown in Fig. 1, C and D, neither of these inhibitors prevented AR activation in either of the two models. From these results we conclude that eNOS is the most likely source of AR activation in the ischemic heart and that neuronal NOS and inducible NOS do not play a significant role in this process.

FIGURE 1.

Activation of AR in the ischemic heart. A, isolated adult male rat hearts were perfused with KH solution for 10 min and then subjected to 15 min of global ischemia (I) or to 15, 20, and 30 min of ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion (I/R). Control hearts (P) were perfused for 70 min. B, rats underwent coronary occlusion (O) for 15 min or 15, 20, and 30 min of occlusion was followed by 30 min of reperfusion (O/R). Sham-operated rats (Sham) served as controls. C, hearts were perfused either for 40 min with KH solution or for 10 min before 30 min of global ischemia or were subjected to 30 min of ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion. For the inhibitor study, hearts were perfused for 10 min before ischemia with KH solution containing either AAEAPNG (0.5 μm) or BBS-2 (0.1 mm) or l-NAME (0.1 mm). D, Sprague-Dawley rats were treated either with AAEAPNG (5 mg/kg; intraperitoneal) or BBS-2 (15 mg/kg; intraperitoneal) or l-NAME (50 mg/kg; intraperitoneal) for 2 days before surgery. Control rats were treated with buffered saline. Rats were subjected either to coronary occlusion for 30 min or 30 min of coronary occlusion followed by 30 min of reperfusion. Sham-operated rats were used as controls. Tissue from the ischemic zone of the left ventricle was snap-frozen and used for measuring AR and SDH activity, sorbitol content, and for Western blot analyses.*, p < 0.05 compared with the perfused or sham-operated hearts (A and B) or compared with the corresponding parameters in the absence of inhibitors (C and D); **, p < 0.05 compared with the 15 min of ischemia or occlusion followed by 30 min of reperfusion; #, p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding parameter in the perfused or sham-operated hearts (n = 3).

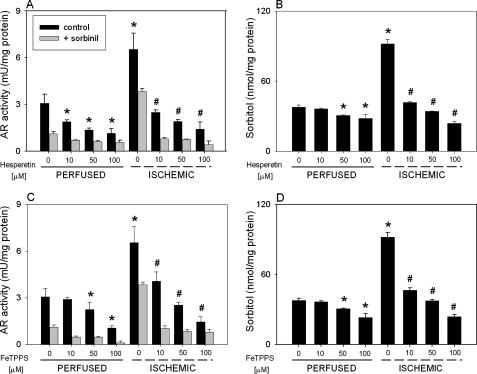

AR Is Activated by Peroxynitrite—We had previously reported that activation of AR in the ischemic heart could be prevented by superoxide scavengers (17). Because generation of both superoxide (31) and NO (32) is increased during ischemia, we reasoned that AR activation may be dependent upon formation of their product, peroxynitrite. To examine the role of peroxynitrite, isolated hearts were perfused with a peroxynitrite scavenger, hesperetin, or a peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, FeTPPS. Both hesperetin and FeTPPS have previously been shown to be potent scavengers of peroxynitrite (33). Our results show that treatment with 10–100 μm hesperetin or FeTPPS led to a significant dose-dependent reduction of AR activation and sorbitol content in both perfused and ischemic hearts (Fig. 2, A–D). These results suggest that activation of AR in the ischemic heart may be due to peroxynitrite. Because small quantities of peroxynitrite could be formed also in the perfused heart (34, 35), peroxynitrite could also account for AR activation under non-ischemic conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Peroxynitrite scavengers prevent ischemic activation of AR. Rat hearts were perfused (P) for 40 min with KH solution alone or KH solution containing the indicated concentrations of hesperetin or FeTPPS or were equilibrated with KH solution with or without hesperetin and FeTPPS for 10 min and then subjected to 30 min of global ischemia. Left ventricular tissue was snap-frozen and used for measuring AR activity in the absence or presence of 1 μm sorbinil (A and C) and sorbitol content (B and D) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” p < 0.05 (*) compared with the corresponding parameter in the perfused hearts and p < 0.05 (#) compared with the ischemic hearts, both in the absence of peroxynitrite scavengers (n = 3).

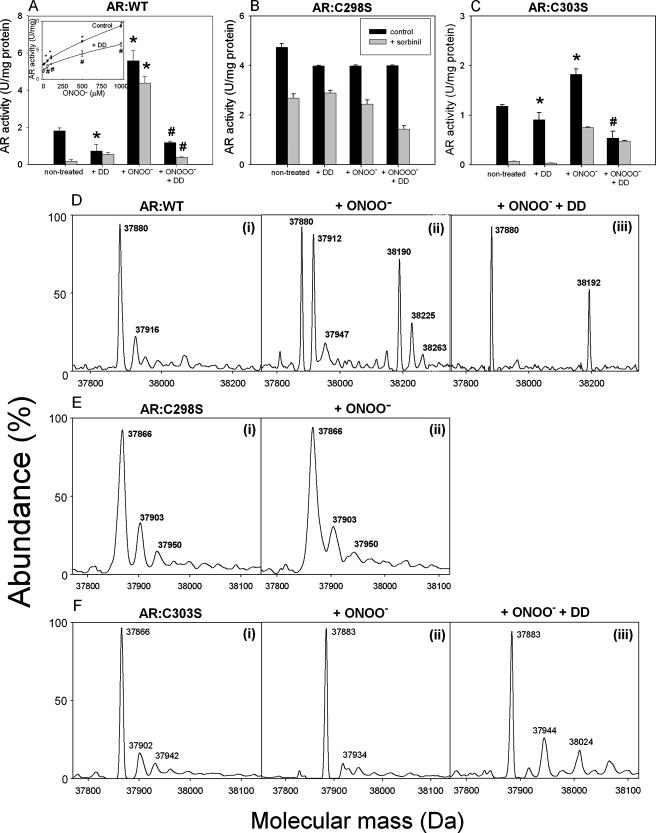

To determine whether peroxynitrite activates AR directly, we examined the effects of peroxynitrite on the kinetic properties of pure AR protein. As shown in the Fig. 3A (inset), incubation of recombinant AR protein with 0.1–1 mm peroxynitrite for 1 h caused a dose-dependent increase in AR activity. At 1 mm peroxynitrite, a 4-fold increase in AR activity was observed. Treatment with peroxynitrite also diminished the inhibitor sensitivity of the enzyme. Although 80% of the activity of the fully reduced non-treated enzyme was inhibited by 1 μm sorbinil, only 20% of the peroxynitrite-modified enzyme was inhibited by the same concentration of sorbinil. Because a decrease in sorbinil sensitivity indicates cysteine oxidation of AR (17), these data suggest that treatment with peroxynitrite causes oxidative modification of AR cysteines. To examine whether this modification is due to oxidation of the cysteines to sulfenic acid, the peroxynitrite-modified enzyme was treated with dimedone, which binds selectively to protein sulfenic acids (36) and abolishes ischemic activation of AR (17). As shown in the Fig. 3A, incubation of un-modified AR with dimedone led to a slight decrease in AR activity (presumably due to the presence of sulfenic acids in the non-treated protein). Treatment with dimedone caused a marked decrease in the activity of the peroxynitrite-treated enzyme. The residual activity of the peroxynitrite and dimedone-treated enzyme was sensitive to sorbinil, indicating that this is due to the unmodified form of the enzyme in which the cysteine residues are in the reduced state. Measurements of steady-state kinetic parameters revealed that treatment of AR with peroxynitrite did not affect the Km (glyceraldehyde) of the enzyme, although Vmax was increased 2.5-fold (Table 1). Dimedone by itself did not affect either the Km or the Vmax of the enzyme; however, it prevented peroxynitrite-mediated change in the Vmax (Table 1). When AR was modified with peroxynitrite, dimedone treatment caused a 3-fold increase in Km of the enzyme, suggesting that binding of dimedone inhibits AR by decreasing the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that peroxynitrite could directly activate AR by oxidizing its cysteine residues to sulfenic acids and that the peroxynitrite-modified protein displays kinetic properties similar to those of the enzyme in the ischemic heart (17).

FIGURE 3.

Peroxynitrite activates AR by oxidizing cysteine residues to sulfenic acid. Human recombinant AR:WT (A), AR:C298S (B), and AR:C303S (C) proteins were incubated with 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0 alone, or buffer containing 0.5 mm dimedone (+DD) for 30 min or 0.1 mm peroxynitrite (+ONOO-) for 1 h at 4 °C. In additional experiments the protein was first incubated with ONOO- for 1 h and then with dimedone for 30 min. At the end of the protocol, components of the reaction mixture were removed by a rapid gel filtration, and AR activity was measured in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, either in the absence or presence of 1 μm sorbinil. Inset to panel A shows dose-dependent activation of AR by ONOO-. AR:WT protein was incubated with 10, 50, 100, 500, and 1000 μm ONOO- alone (control), or subsequently with dimedone. After 1 h of incubation protein was desalted on PD-10 column, and AR activity was measured as described above. Shown are ESI mass spectra of AR:WT (D), AR:C298S (E), and AR:C303S (F) protein treated either with 0.1 mm ONOO- for 1 h (ii) or desalted and incubated with 0.5 mm dimedone for 30 min after the treatment with 0.1 mm ONOO- (iii). p < 0.05 (*) compared with the non-treated hearts and p < 0.05 (#) compared with the ONOO--treated hearts (n = 3).

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of AR:WT treated with peroxynitrite (ONOO–) and dimedone Human His tag AR:WT was reduced for 1 h with 0.1 m DTT, desalted, and incubated for 1 h either with 0.1 mm peroxynitrite or for 30 min with 0.5 mm dimedone in 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.0. Additionally, peroxynitrite-modified protein was treated with 0.5 mm dimedone for 30 min. Incubation of the enzyme was terminated by the gel filtration of the mixture on PD-10 columns. n = 3.

| Km | Vmax | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | (U/mg/min) | ||

| Control | 124.1 ± 3.3 | 1.58 ± 0.07 | 0.9951 |

| +Dimedone | 173.4 ± 2.5 | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 0.9577 |

| +ONOO– | 97.3 ± 2.3 | 3.96 ± 0.09 | 0.9945 |

| +ONOO– + dimedone | 428.7 ± 9.3 | 1.22 ± 0.04 | 0.9847 |

The AR protein contains three solvent-exposed cysteines, i.e. Cys-80, Cys-298, and Cys-303 (28). Analysis of AR from the ischemic heart shows that both Cys-298 and Cys-303 are oxidized to sulfenic acids (17). To identify which of these residues is modified by peroxynitrite, site-directed mutants of AR were prepared in which each of these cysteines was individually replaced by serine. As shown in the Fig. 3B, treatment with peroxynitrite did not significantly affect the catalytic activity of AR:C298S; moreover, this enzyme was also insensitive to dimedone. In contrast, AR:C303S was activated by peroxynitrite, and the peroxynitrite-modified protein was inhibited by dimedone, indicating that peroxynitrite treatment induces sulfur oxy-acid formation in this protein. Interestingly, the dimedone-treated protein was sensitive to sorbinil, indicating that mutation of the Cys-303 affects the ability of Cys-298 to regulate inhibitor sensitivity. Regardless, these results clearly indicate that Cys-298 is the major site of sulfenic acid formation and that oxidation of Cys-298 is necessary and sufficient for AR activation by peroxynitrite.

The modification of AR by peroxynitrite was further studied by ESI/MS. Mass spectra profile of the reduced, untreated protein revealed that the charge states of WT AR correspond to two species; that is, a major peak, with a molecular mass of 37,880 Da and a minor peak with a molecular mass of 37,916 Da (Fig. 3D, i). The major peak was assigned to the native, unmodified AR (expected mass, 37,883 Da). The identity of the 37,916-Da peak is unclear, but it may be due to oxidation of the protein to sulfenic acid during sample preparation (expected mass for 2 sulfenic acids, 37,915 Da). Treatment with peroxynitrite (Fig. 3D, ii) led to the appearance of two new species with molecular masses of 37,912 and 37,947 Da. These species differ from the parent species by 32 Da, consistent with the addition of two atomic oxygen mass units to the protein. Additional peaks at 38,190, 38,225, and 38,263 Da were also observed. Because these species appeared only upon treatment with peroxynitrite they may correspond to the variably nitrosylated forms of the protein or the protein bound to several peroxynitrite molecules. When treated with dimedone, the peroxynitrite-modified protein conformed to two major species (Fig. 3D, iii), a native unmodified form (37,880 Da) and modified protein form containing two sulfenic acids (+16) and 2 dimedone molecules (+140 Da), which could account exactly for the observed increase in mass of +312 Da. That other species, 37,947, 38,190, 38,225, and 38,263 Da, disappear after dimedone treatment further supports the notion that they may correspond to the intermediate or unstable forms of modified AR. As expected, AR:C298S was resistant to oxidation by peroxynitrite. The unmodified protein showed a major peak at the expected molecular mass of 37,866 Da. Although small unidentified peaks at 37,903 and 37,950 Da were also observed (Fig. 3E, i), they were not affected by peroxynitrite treatment (Fig. 3E, iii). In contrast, treatment of AR:C303S with peroxynitrite led to a 17 Da increase in mass, which within error, will be consistent with the addition of a single oxygen atom (16 Da) to the protein. Treatment with dimedone led to the appearance of a 38,024 Da peak, which was assigned to AR-dimedone adduct (Fig. 3F, iii). The identity of the 37,944 Da peak could not be established. Thus, despite the difference from the WT form, persistent modification of AR:C303S suggests that Cys-298 is the major site of peroxynitrite-induced modification of AR.

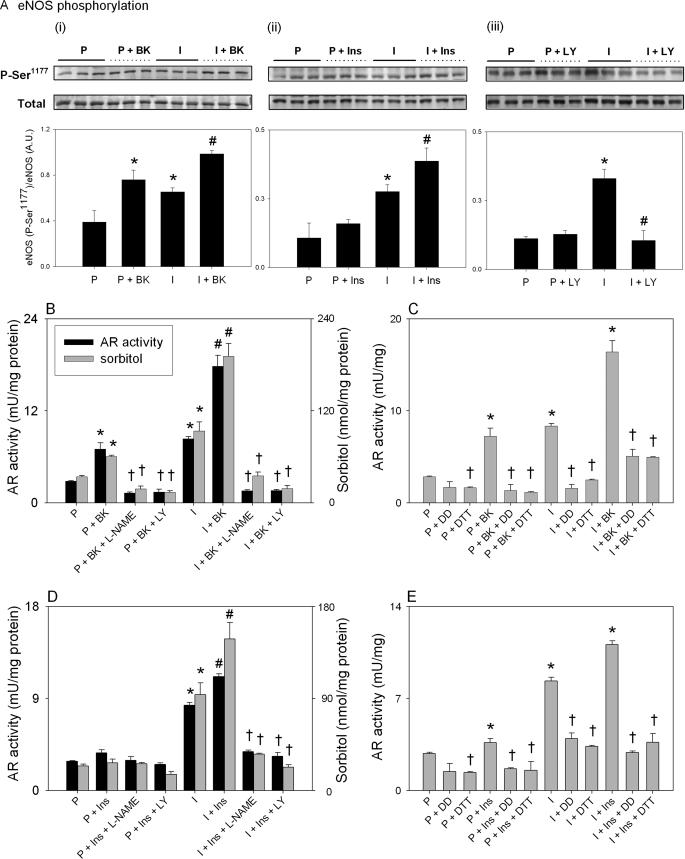

Ischemia, Bradykinin, and Insulin Affect eNOS Phosphorylation—The preceding results indicate that activation of AR in the ischemic heart is due to eNOS-mediated peroxynitrite generation. Although eNOS generates basal levels of NO, its activity is increased by as much as 40-fold upon phosphorylation by Akt at Ser-1177 (37). The serine-threonine protein kinase B or Akt could in turn be activated by the stimulation of Gq-linked receptors, such as the bradykinin B2 (38, 39), or the insulin receptor (40). To examine eNOS activation by ischemia, we measured changes in phosphorylation state of Ser-1177. As shown in the Fig. 4A, i–iii, ischemia induced a 2–3-fold increase in eNOS phosphorylation at Ser-1177, which was completely prevented by inhibiting PI3K with LY294002 (Fig. 4A, iii). Treatment with bradykinin (Fig. 4A, i) and insulin (Fig. 4A, ii) induced an ∼2-fold increase in eNOS phosphorylation in both aerobic and ischemic hearts. These data indicate that eNOS is activated in the ischemic heart and upon stimulation with agonists bradykinin and insulin. Although, phosphorylated neuronal NOS was detected in naïve rat hearts using anti-phospho-Ser-1417 antibodies, no increase in neuronal NOS phosphorylation was observed either with ischemia, bradykinin, or insulin (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

AR activation is regulated by the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Hearts from adult male rats were perfused (P) either with KH solution for 40 min or for 10 min followed by 30 min of global ischemia (I). Hearts perfused with KH solution were also treated with either 0.1 μm bradykinin (BK), 0.1 mm l-NAME, or LY294002 (LY) for additional 15 min or 0.1 μm insulin (Ins) or insulin + l-NAME or LY294002. In the ischemic group, the hearts were treated with the same concentrations of BK, insulin, l-NAME, or LY294002 15 min before ischemia. At the end of each protocol the hearts were snap-frozen, and AR activity, sorbitol content, and eNOS phosphorylation in LV tissue were determined. A, Western blot showing phosphorylation (P) of eNOS at Ser-1177 in the hearts treated with bradykinin (i), insulin (ii), and LY294002 (iii). The lower panels show relative band densities of the phospho-eNOS normalized to total eNOS protein. Effect of bradykinin (B) and insulin (D) on ischemic activation of AR. Panels C and E show AR activity in left ventricular tissue after the indicated treatment protocols followed by the incubation of the tissue homogenates with 0.5 mm dimedone (DD) for 30 min or 1 h of reduction of the homogenates with 100 mm DTT. p < 0.05 (*) compared with the corresponding parameter in the perfused hearts, p < 0.05 (#) compared with the corresponding parameter in the ischemic hearts, and p < 0.05 (†) compared with the perfused and ischemic hearts without DTT or dimedone (n = 3).

AR Activation Is Regulated by the PI3K/Akt/eNOS Pathway— To determine whether intrinsic stimulation of NO production affects AR activity, we studied the effects of bradykinin. When aerobic hearts were treated with bradykinin, a 2-fold increase in AR activity and tissue sorbitol accumulation was observed (Fig. 4B) consistent with the hypothesis that an endogenous increase in NO production activates AR. However, AR activation was prevented by pretreating the hearts with l-NAME, confirming that the effects of bradykinin are mediated through NOS. Furthermore, the bradykinin-induced increase in AR activity was prevented by treating the hearts with LY294002, consistent with the idea that stimulation of eNOS by bradykinin is mediated by PI3K (38, 39). When the hearts were treated with bradykinin and then subjected to ischemia, a 10-fold increase in AR activity and sorbitol accumulation was observed. This increase in AR activity was significantly greater than that due to either ischemia or bradykinin alone, indicating that bradykinin and ischemia have additive effects on AR activity. In the ischemic heart, a bradykinin-induced increase in AR activity was strongly suppressed by the treatment with either l-NAME or LY294002, indicating that as in the aerobic heart, in the ischemic heart bradykinin-induced AR activation was dependent upon activation of both eNOS and PI3K. Collectively, these data support the inference that in both aerobic and ischemic hearts an increase in the intrinsic production of NO leads to AR activation.

To further probe the role of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway, we studied the effects of insulin. It has been shown before (40) that insulin stimulates eNOS by activating PI3K and Akt via insulin receptor/insulin receptor substrate-1. As demonstrated in Fig. 4D, treatment of isolated perfused hearts with insulin had a modest effect on AR activity and the levels of myocardial sorbitol. However, when the hearts were treated with insulin before ischemia, a significant increase in AR activity and sorbitol accumulation was observed which was statistically greater than the extent of AR activation induced by ischemia alone. As with bradykinin, insulin-mediated AR activation was prevented by either l-NAME or LY294002. Hence, taken together the data obtained with bradykinin and insulin indicate that ischemic activation of AR is enhanced by stimulating NO production, and it is prevented either by inhibiting NO synthesis or by interrupting signaling pathways that increase NO synthesis by eNOS.

Bradykinin and Insulin Activate AR by Sulfenic Acid Formation—Several mechanisms could in principle account for AR activation in bradykinin- or insulin-treated hearts. Hence, to determine whether increase in AR activity is due to oxidation of its cysteine residues to sulfenic acid, homogenates prepared from bradykinin- or insulin-treated hearts were reduced for 1 h with 0.1 m DTT or were incubated with 0.5 mm dimedone for 30 min. As shown in the Fig. 4, C and E, treatment of the homogenates with both DTT and dimedone reversed the increase in AR activity observed in the ischemic as well as the perfused hearts or in the ischemic hearts treated with bradykinin or insulin, respectively. These observations support the notion that stimulation of AR activity by ischemia, bradykinin, or insulin (in both ischemic and non-ischemic hearts) is due to oxidation of the cysteine residues of the protein to sulfenic acids.

Ischemic Activation of AR Confers Cardioprotection—Our results above show that activation of AR in the ischemic heart is mediated by a PI3K/Akt/eNOS-dependent mechanism. Because activation of eNOS via the PI3K/Akt pathway has a cardioprotective effect (40), we tested the hypothesis that NO-mediated AR activation may be required for cardioprotection.

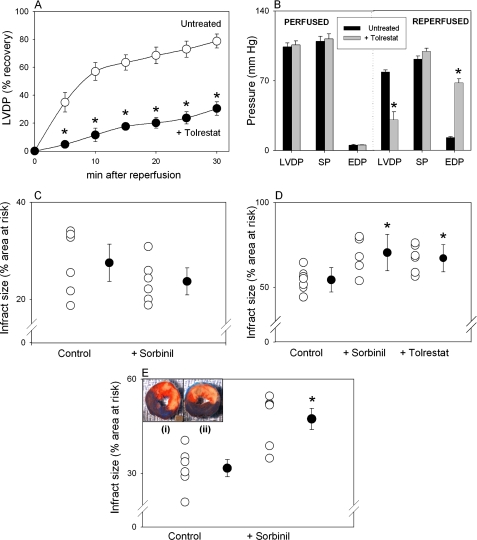

To study the protective role of AR, we used both ex vivo and in situ models of myocardial ischemia. For these experiments rat hearts were either perfused and subjected to global ischemia-reperfusion or subjected to coronary ligation in situ in the presence or absence of AR inhibitors sorbinil or tolrestat. Both compounds are highly selective and effective in inhibiting AR with a Ki of 1 and 0.01 μm, respectively (41). Under the conditions used, the left ventricular-developed pressure (LVDP) by isolated perfused hearts was 104 ± 4 mm Hg (n = 8), and the systolic pressure was 109.5 ± 5 mm Hg when the left ventricular end diastolic pressure was kept at 5.2 ± 0.1 mm Hg. The heart rate was 332 ± 30/min, and the coronary flow was 14.1 ± 0.7 ml/min. After 30 min of ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion, the LVDP was 91.9 ± 3 mm Hg, and the end-diastolic pressure was 12.9 ± 1.0 mm Hg. Thus, % recovery in LVDP was 76 ± 2%. The time course of recovery in LVDP is shown in the Fig. 5A. Although treatment with 10 μm tolrestat did not significantly affect pre-ischemic function of the hearts (Fig. 5B), the recovery of function after 30 min of ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion was only 29 ± 7%, which was significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared with untreated hearts (Fig. 5A). There was no significant change in systolic pressure (89 ± 2% in tolrestat-treated versus 84 ± 3% in control hearts). The poorer recovery of tolrestat-treated hearts was accompanied by a persistently elevated end-diastolic pressure (68 ± 4 mm Hg after 30 min of reperfusion). Coronary flow and heart rate were not significantly affected by tolrestat treatment (Fig. 5B). Overall, poor recovery of function in tolrestat-treated hearts was associated with poor recovery in the rate-pressure product (22 ± 6% versus the untreated hearts 74 ± 3%; p < 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of AR exacerbates ischemic injury. A, time course of % recovery of LVDP in isolated rat hearts subjected to 30 min of global ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion in the absence (Untreated) and presence of 10 μm tolrestat. B, values of LVDP, systolic pressure (SP), and end-diastolic pressure (EDP) in untreated and tolrestat-treated perfused hearts before (PERFUSED) and after 30 min of ischemia followed by 30 min of reperfusion (REPERFUSED). Effect of AR inhibition on ischemic injury in adult male rats treated with sorbinil or tolrestat (40 mg/kg; intraperitoneal, both) and then subjected to either 20 min (C) or 30 min (D) of coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion. Control rats were treated with Me2SO. E, ischemic injury determined in rats subjected to 30-min of coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion in which sorbinil (40 mg/kg, intravenous) was administered 5 min before reperfusion. Inset to the panel E, representative micrographs of rat heart tissue after the 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining. Dark blue, non-ischemic zone; red, area at risk; pink, infracted area; p < 0.05; (*), compared with the control or untreated hearts (n = 6–9).

In vehicle-treated rats subjected to 20 min of coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion, 27.5 ± 2.8% of the area-at-risk was infracted (Fig. 5C). This was not affected in the rats pretreated with sorbinil (23.7 ± 3.8%). On the other hand, when the rats were subjected to longer, 30-min coronary occlusion followed by 24 h of reperfusion, 54.3 ± 2.2% of the area-at-risk was infracted (Fig. 5D), which was increased to 67 ± 3.3 and 70.4 ± 4.3% in the rats pretreated with sorbinil or tolrestat, respectively. To examine whether AR protects against injury during reperfusion, rats were subjected to 30 min of coronary occlusion, and sorbinil was administered 5 min before reperfusion. A significant increase in infarct size from 31.7 ± 2.7 to 47.4 ± 3.4% (p < 0.05) was observed (Fig. 5E).

Collectively, these findings indicate that AR protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury only during the late stages of ischemia and during reperfusion. Inhibition of AR during shorter periods of ischemia (≤20 min) did not affect ischemic injury, consistent with the idea that activation of AR at early stages of ischemia is required for subsequent protection.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study are that activation of AR in the ischemic heart is prevented by inhibiting NO synthesis and peroxynitrite formation and that the enzyme is activated by increasing endogenous NO production via eNOS. These results suggest that the peroxynitrite-induced formation of sulfenic acids on AR cysteines (preferentially at Cys-298) may be a regulated physiological response to ischemia and a part of an adaptation mechanism protecting the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Although the in vitro and in vivo formation of sulfenic acid derivatives of several enzymes and proteins have been described before (36, 42), to the best of our knowledge this is the first report identifying a specific signaling pathway, PI3K/Akt/eNOS, regulating the formation of sulfur oxy-acids on a protein to change its function.

Transient oxidation of active site cysteines to sulfenic acid intermediates is a significant feature of the catalytic cycle of several enzymes including NADH oxidase, peroxiredoxin, methionine sulfoxide reductase (36, 42), and the formyl-glycine-generating enzymes (43). In addition, it has also been reported that the formation of metastable sulfenic acids regulates the function of the bacterial transcription factor OxyR and the Ohr repressor as well as the yeast Xap1-Gpx3 complex (36). The role of sulfenic acids in regulating signal transduction pathways and gene transcription events in mammalian cells, however, has been less well studied, and no specific signaling mechanism regulating sulfenic acid formation on the proteins has been described.

Our previous studies show that myocardial ischemia leads to oxidation of AR cysteine residues to sulfenic acid (17). Given the close association between ischemia and reactive oxygen species generation (18, 19, 44), we assumed that oxidation of AR cysteines is reflective of oxidative conditions prevailing in the ischemic heart. This view was supported by the observation that antioxidant interventions that scavenge reactive oxygen species prevented AR activation in the ischemic heart (17). However, additional investigations into the mechanism of AR activation reported here reveal that in addition to reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide is also necessary for AR activation. We found that in the ischemic heart, stimulation of endogenous NO production (by bradykinin or insulin) increased AR activity, whereas inhibition of NO synthesis or scavenging peroxynitrite prevented AR activation. Taken together, these observations support the novel paradigm that AR activation during ischemia is due to NO-mediated oxidation of AR cysteines to sulfenic acid.

The reactions of NO with protein thiols are complex. Although NO by itself does not react directly with thiols, oxidized forms of NO (N2O3 or NO+) readily nitrosylate cysteine side chains of the proteins (45–47). Nitrosylated thiols are more reactive and could be readily converted to disulfides or oxidized to sulfenic, sulfinic, or sulfonic acids. Reactions of NO with free sulfhydryl residues have also been shown to yield sulfenic acids in several proteins (48–50); however, induction of sulfenic acids in intracellular proteins by NO in vivo has not been reported. Furthermore, in the ischemic heart activation of AR was prevented either by inhibiting NO synthesis (Fig. 1, C and D) or by scavenging superoxide (25) or peroxynitrite (Fig. 2). In addition, incubation with peroxynitrite led to the formation of sulfenic acid in purified AR protein as authenticated by dimedone reactivity (Fig. 3, A–C) and mass spectrometry (Fig. 3, D–F). Activation and modification of AR was prevented by replacing Cys-298 with serine, confirming that oxidation of Cys-298 residue is responsible for AR activation. Collectively, this evidence provides strong support to the notion that in the ischemic heart, NO-dependent activation of AR is due to peroxynitrite-induced sulfenic acid formation. These data represent the first reported example of peroxynitrite-dependent intracellular sulfenic acid formation in vivo. The role of peroxynitrite in activating AR in the ischemic heart is not surprising. Despite being considered a harmful byproduct of the reaction between NO and superoxide causing tissue injury under a variety of pathological conditions (51) such as heart failure (52), sudden cardiac death (53), and the depression of myocardial contractility due to endotoxin (54) or overproduction of cytokines (35), emerging evidence suggests the possibility that at low levels peroxynitrite could have a signaling role. For instance, stimulation of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase by NO during arterial relaxation has recently been shown to be mediated by peroxynitrite-induced glutathiolation (55). Moreover, treatment with peroxynitrite prevents ischemic injury, indicating that peroxynitrite formation may be cardioprotective (56). Additionally, the cardioprotective effects of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning, which are prevented by scavenging either NO or superoxide, have been linked to endogenously generated peroxynitrite (57). In agreement with this idea, our data showing that peroxynitrite activates AR in the ischemic heart supports the general concept that peroxynitrite is a second messenger that transmits intracellular signals by specific and regulatable modification of protein thiols to sulfenic acid. Indeed, peroxynitrite is well suited for such a signaling role. It reacts with protein cysteines at a rate constant which is 3 orders of magnitude greater than hydrogen peroxide. Moreover, unlike hydrogen peroxide, which readily reacts with thiolated anion, peroxynitrite reacts preferentially with the undissociated form of the thiolate anion (58). Therefore, the range of thiols accessible to peroxynitrite is likely to be much greater than that available to hydrogen peroxide. Moreover, tissue acidification during ischemia would favor sulfhydryl modification by peroxynitrite over that due to hydrogen peroxide. In this regard, AR may be a particularly sensitive target of peroxynitrite because its active site cysteines (Cys-298 and Cys-303) are highly reactive and the sulfenic acid product of the reaction is likely to be stabilized by the strongly hydrophobic environment of the NADPH-bound spatially occluded active site at the bottom of the β-barrel (2).

Sulfenic acid formation may be one of the several discrete modifications of AR induced by endogenous NO or peroxynitrite production. We cannot formally discount the possibility that other modified forms of AR exist in the ischemic heart or that the protein is first nitrosylated and then oxidized to sulfenic acid. Indeed, our ESI/MS analyses show that treatment with peroxynitrite results in the generation of several transiently modified forms of AR (Fig. 3D, ii). Moreover, because nitrosylation (22), like sulfenic acid formation (17), leads to an increase in AR activity, these two types of modification cannot be kinetically distinguished. However, we observed that ischemic modification increases the reactivity of AR to dimedone (Fig. 3, A–C) and that peroxynitrite-modified protein forms sulfenic acid-dimedone adducts (Fig. 3D, iii). These observations, when analyzed together with our previous data showing that AR from the ischemic heart is a sulfenic acid derivative and is inhibited by dimedone (17), provide strong support to the idea that peroxynitrite-mediated activation of AR in the ischemic heart is due to oxidation of AR cysteines to sulfenic acids.

Our previous studies show that exposure to NO donors activates AR by nitrosylating cysteine residues (22) and that GSNO inhibits AR activity by glutathiolation (21). Indeed, these modifications have been shown to regulate the intracellular activity of AR (23, 24). Hence, it appears likely that in addition to sulfenic acid derivatives, nitrosylated and glutathiolated forms of AR are also present in the heart. The presence of these forms is suggested by our observation that in the perfused hearts inhibition of NOS causes inhibition of AR (Fig. 1A), whereas sham hearts treated with l-NAME in situ show an increase in AR activity and sorbitol accumulation (Fig. 1B). Even though the reasons for such divergent responses to NOS inhibition remain unclear, we speculate that ex vivo perfusion causes AR nitrosylation or sulfenic acid formation due to high oxygen concentrations achieved in the perfused heart, whereas in the in situ model (at low pO2), most of AR is inhibited due to glutathiolation, which is relieved by inhibiting NOS. Further studies are required to identify which specific forms of AR are present in the heart and how they are regulated by the range of oxygen concentrations prevalent in the normal and ischemic hearts. Regardless, the data available to-date indicate that AR is highly sensitive to oxygen, NO, and peroxynitrite levels and suggest the general possibility that unlike all-or-none off-and-on states induced by phosphorylation, cysteine-based modifications could generate a wide range of graded and interchangeable modifications in the protein structure and function. That such modifications are not merely a consequence of highly oxidative conditions encountered during near death situations is suggested by our observation showing that treatment with physiologically relevant concentrations of bradykinin, even in the non-ischemic heart, leads to AR activation due to thiol modification (Fig. 4, C and E) and that bradykinin and insulin induce eNOS phosphorylation and subsequent AR activation in both the normal and ischemic heart (Fig. 4A, i-iii). Because both bradykinin and insulin increase NO production, these observations suggest that in the ischemic heart NO, not superoxide production, is rate-limiting for AR activation. Our findings also reinforce the idea that induction of sulfenic acid formation in AR is not directly due to a sudden increase in superoxide production (which is unlikely to be affected by insulin or bradykinin) or some other spurious oxidative events but is a controlled event triggered in response to an increase in NO production. A regulated increase in AR activity via PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway, which provides protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury (38, 59, 60), is consistent with the cardioprotective role of this protein. However, reports on the role of AR in ischemia-reperfusion injury are contradictory. Inhibition of AR in rat hearts subjected to low-flow or shorter (≤20 min) durations of ischemia has been shown to improve functional recovery and ATP content (15). In rabbit hearts inhibition of AR has been shown to be mildly protective (61), although it has also been reported to abolish the cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning (10). Recent work with AR transgenic mice demonstrates that overexpression of AR increases ischemic injury (62). Reasons for such results, discordant with the protective role of AR reported here, are not clear but may be due to model-dependent variations. Specifically, earlier studies (13, 62) used palmitate in the perfusion buffer. In contrast, we used glucose as a sole substrate. Palmitate could inhibit glucose oxidation, delay recovery of pH, and significantly impair the recovery of mechanical function (63–66). These factors could affect the role of AR, which may be different in the presence of palmitate than in the presence of glucose alone. For instance, inhibition of AR in the presence of palmitate may limit glycolysis, whereas glycolysis may not be affected when 10 mm glucose is the sole substrate. Indeed, given such limitation of perfused heart preparations, we tested the effects of AR inhibition in a more physiological model of coronary occlusion. Results from this model clearly indicate that inhibition of AR exacerbates post-ischemic injury (Fig. 5, D and E), indicating that under conditions prevailing in situ, AR is likely to be a cardioprotective protein.

The mechanisms by which activated AR protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury remain unclear. We propose that AR protects the heart by removing toxic aldehydes generated in the ischemic heart. Although additional experiments are required to fully evaluate this hypothesis, extensive data show that AR catalyzes reduction of phospholipid-derived aldehydes and their glutathione conjugates (4, 5) and that inhibition of AR causes accumulation of these aldehydes in the ischemic heart (10). This supports the notion that AR-mediated cardioprotection may be related to more efficient removal of toxic lipid peroxidation products. Although AR has broad substrate specificity, the enzyme also catalyzes the reduction of glucose. Hence, under certain conditions excessive reduction of glucose via AR could inhibit glycolysis and thereby exaggerate ischemic injury. Additionally, reduction of glucose by AR generates sorbitol, which is further reduced to fructose by SDH. Increased activity of this pathway results in net depletion of NADPH and accumulation of NADH, which could inhibit respiration and compromise antioxidant defense. Indeed, it has been shown that inhibition of SDH prevents ischemic injury in isolated perfused hearts (67). However, the observation that sorbitol concentrations increase with an increase in AR activity (Fig. 1) indicates that not all of the sorbitol generated by AR is effectively reduced by SDH. Although SDH activity detected in the rat hearts, it was only 10% of that in the liver (data not shown). Clearly, more in-depth studies are required to assess the significance of sorbitol formation in the ischemic heart and to identify specific metabolic conditions under which AR activation could either prevent or augment ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury. In summary, results of the current study show that cardioprotective activation of AR in the ischemic heart due to formation of sulfur-oxy-acids in the protein is a regulated posttranslational event mediated by increased production of NO from eNOS and is regulated upstream by the PI3K/Akt pathway. These observations indicate an unrecognized mode of NO signaling in the ischemic heart leading to the formation of protein-sulfenic acids. Based on these results, we speculate that during increased oxidative stress NO engages similar mechanisms of redox signaling in other tissues also. The general significance of this “new” mode of NO signaling remains to be fully assessed.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL55477, 59378, 65618, 78825, ES11594, and 11860 and a postdoctoral fellowship from the America Heart Association. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AR, aldose reductase; SDH, sorbitol dehydrogenase; LV, left ventricle; LVDP, LV-developed pressure; L-NAME, N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; FeTPPS, 5, 10, 15, 20-tetrakis-[4-sulfonatophenyl]-porphyrinato-iron [III]; ESI/MS, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; NOS, nitric-oxide synthase; eNOS, endothelial NOS; LY294002, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one; AAEAPNG, N-[(4S)-4-amino-5-[(2-amino-ethyl)-(aminopentyl)]-N′-nitroguanidine; DTT, dithiothreitol; KH solution, Krebs-Henseleit solution; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; WT, wild type.

References

- 1.Bhatnagar, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (1992) Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol. 48 91-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava, S. K., Ramana, K. V., and Bhatnagar, A. (2005) Endocr. Rev. 26 380-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava, S., Chandra, A., Wang, L. F., Seifert, W. E., Jr., DaGue, B. B., Ansari, N. H., Srivastava, S. K., and Bhatnagar, A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 10893-10900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava, S., Watowich, S. J., Petrash, J. M., Srivastava, S. K., and Bhatnagar, A. (1999) Biochemistry 38 42-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava, S., Spite, M., Trent, J. O., West, M. B., Ahmed, Y., and Bhatnagar, A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 53395-53406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixit, B. L., Balendiran, G. K., Watowich, S. J., Srivastava, S., Ramana, K. V., Petrash, J. M., Bhatnagar, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 21587-21595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramana, K. V., Dixit, B. L., Srivastava, S., Balendiran, G. K., Srivastava, S. K., and Bhatnagar, A. (2000) Biochemistry 39 12172-12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rittner, H. L., Hafner, V., Klimiuk, P. A., Szweda, L. I., Goronzy, J. J., and Weyand, C. M. (1999) J. Clin. Investig. 103 1007-1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, J., Moravec, C. S., Sussman, M. A., DiPaola, N. R., Fu, D., Hawthorn, L., Mitchell, C. A., Young, J. B., Francis, G. S., McCarthy, P. M., and Bond, M. (2000) Circulation 102 3046-3052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinmura, K., Bolli, R., Liu, S. Q., Tang, X. L., Kodani, E., Xuan, Y. T., Srivastava, S., and Bhatnagar, A. (2002) Circ. Res. 91 240-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sergeev, P., da Silva, R., Lucchinetti, E., Zaugg, K., Pasch, T., Schaub, M. C., and Zaugg, M. (2004) Anesthesiology 100 474-488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spycher, S. E., Tabataba-Vakili, S., O'Donnell, V. B., Palomba, L., and Azzi, A. (1997) FASEB J. 11 181-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang, Y. C., Sato, S., Tsai, J. Y., Yan, S., Bakr, S., Zhang, H., Oates, P. J., and Ramasamy, R. (2002) FASEB J. 16 243-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramasamy, R., Oates, P. J., and Schaefer, S. (1997) Diabetes 46 292-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramasamy, R., Trueblood, N., and Schaefer, S. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275 H195-H203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vikramadithyan, R. K., Hu, Y., Noh, H. L., Liang, C. P., Hallam, K., Tall, A. R., Ramasamy, R., and Goldberg, I. J. (2005) J. Clin. Investig. 115 2434-2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiserova, K., Srivastava, S., Hoetker, J. D., Awe, S. O., Tang, X. L., Cai, J., and Bhatnagar, A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 15110-15120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downey, J. M. (1990) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 52 487-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloner, R. A., and Jennings, R. B. (2001) Circulation 104 3158-3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra, A., Srivastava, S., Petrash, J. M., Bhatnagar, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1341 217-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra, A., Srivastava, S., Petrash, J. M., Bhatnagar, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (1997) Biochemistry 36 15801-15809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava, S., Dixit, B. L., Ramana, K. V., Chandra, A., Chandra, D., Zacarias, A., Petrash, J. M., Bhatnagar, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (2001) Biochem. J. 358 111-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra, D., Jackson, E. B., Ramana, K. V., Kelley, R., Srivastava, S. K., and Bhatnagar, A. (2002) Diabetes 51 3095-3101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramana, K. V., Chandra, D., Srivastava, S., Bhatnagar, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (2003) FASEB J. 17 417-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiserova, K., Awe, S. O., Srivastava, S., and Bhatnagar, A. (2005) Circulation 112 II-283 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatnagar, A. (1995) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 26 343-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ping, P., Zhang, J., Huang, S., Cao, X., Tang, X. L., Li, R. C., Zheng, Y. T., Qiu, Y., Clerk, A., Sugden, P., Han, J., and Bolli, R. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277 H1771-H1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrash, J. M., Harter, T. M., Devine, C. S., Olins, P. O., Bhatnagar, A., Liu, S., and Srivastava, S. K. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 24833-24840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng, T. F., Lee, F. K., Song, Z. T., Calcutt, N. A., Lee, L. W., Chung, S. S. M., and Chung, S. K. (1998) Diabetes 47 961-966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berges, A., Van Nassauw, L., Timmermans, J. P., and Vrints, C. (2007) Pharmacol. Res. 55 72-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becker, B. L., van den Hoek, T. L., Shao, Z. H., Li, C. Q., and Schumacker, P. T. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277 2240-2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Node, K., Kitakaze, M., Kosaka, H., Komamura, K., Minamino, T., Inoue, M., Tada, M., Hori, M., and Kamada, T. (1996) Circulation 93 356-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lancel, S., Tissier, S., Mordon, S., Marechal, X., Depontieu, F., Scherpereel, A., Chopin, C., and Neviere, R. (2004) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43 2348-2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beckman, J. S., and Koppenol, W. H. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271 C1424-C1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang, Y. C., Bakr, S., Ellery, C. A., Oates, P. J., and Ramasamy, R. (2003) FASEB J. 17 2331-2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole, L. B., Karplus, P. A., and Claiborne, A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44 325-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimmeler, S., Fleming, I., Fisslthaler, B., Hermann, C., Busse, R., and Zeiher, A. M. (1999) Nature 399 601-605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell, R. M., and Yellon, D. M. (2003) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 35 185-193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie, P., Browning, D. D., Hay, N., Mackman, N., and Ye, R. D. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 24907-24914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao, F., Gao, E., Yue, T. L., Ohlstein, E. H., Lopez, B. L., Christopher, T. A., and Ma, X. L. (2002) Circulation 105 1497-1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatnagar, A., Liu, S. Q., Das, B., Ansari, N. H., and Srivastava, S. K. (1990) Biochem. Pharmacol. 39 1115-1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claiborne, A., Yeh, J. I., Mallett, T. C., Luba, J., Crane, E. J., III, Charrier, V., and Parsonage, D. (1999) Biochemistry 38 15407-15416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dierks, T., Dickmanns, A., Preusser-Kunze, A., Schmidt, B., Mariappan, M., von, Figura K., Ficner, R., and Rudolph, M. G. (2005) Cell 121 541-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kloner, R. A., Przyklenk, K., and Whittaker, P. (1989) Circulation 80 1115-1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hess, D. T., Matsumoto, A., Kim, S. O., Marshall, H. E., and Stamler, J. S. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 150-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez-Ruiz, A., and Lamas, S. (2004) Cardiovasc. Res. 62 43-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stamler, J. S., Lamas, S., and Fang, F. C. (2001) Cell 106 675-683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeMaster, E. G., Quast, B. J., Redfern, B., and Nagasawa, H. T. (1995) Biochemistry 34 11494-11499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishii, T., Sunami, O., Nakajima, H., Nishio, H., Takeuchi, T., and Hata, F. (1999) Biochem. Pharmacol. 58 133-143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Percival, M. D., Ouellet, M., Campagnolo, C., Claveau, D., and Li, C. (1999) Biochemistry 38 13574-13583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pacher, P., Beckman, J. S., and Liaudet, L. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87 315-424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ungvari, Z., Gupte, S. A., Recchia, F. A., Batkai, S., and Pacher, P. (2005) Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 3 221-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mungrue, I. N., Gros, R., You, X., Pirani, A., Azad, A., Csont, T., Schulz, R., Butany, J., Stewart, D. J., and Husain, M. (2002) J. Clin. Investig. 109 735-743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flesch, M., Kilter, H., Cremers, B., Laufs, U., Sudkamp, M., Ortmann, M., Muller, F. U., and Bohm, M. (1999) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 33 1062-1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adachi, T., Weisbrod, R. M., Pimentel, D. R., Ying, J., Sharov, V. S., Schoneich, C., and Cohen, R. A. (2004) Nat. Med. 10 1200-1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nossuli, T. O., Hayward, R., Scalia, R., and Lefer, A. M. (1997) Circulation 96 2317-2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bolli, R. (2000) Circ. Res. 87 972-983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radi, R., Beckman, J. S., Bush, K. M., and Freeman, B. A. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 4244-4250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujio, Y., Nguyen, T., Wencker, D., Kitsis, R. N., and Walsh, K. (2000) Circulation 101 660-667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsui, T., Tao, J., del, M. F., Lee, K. H., Li, L., Picard, M., Force, T. L., Franke, T. F., Hajjar, R. J., and Rosenzweig, A. (2001) Circulation 104 330-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tracey, W. R., Magee, W. P., Ellery, C. A., MacAndrew, J. T., Smith, A. H., Knight, D. R., and Oates, P. J. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 279 1447-1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iwata, K., Matsuno, K., Nishinaka, T., Persson, C., and Yabe-Nishimura, C. (2006) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 102 37-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Folmes, C. D., Clanachan, A. S., and Lopaschuk, G. D. (2006) Circ. Res. 99 61-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnston, D. L., and Lewandowski, E. D. (1991) Circ. Res. 68 714-725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu, Q., Docherty, J. C., Rendell, J. C., Clanachan, A. S., and Lopaschuk, G. D. (2002) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 39 718-725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rochette, L., Didier, J. P., Moreau, D., and Bralet, J. (1980) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2 267-279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferdinandy, P., Danial, H., Ambrus, I., Rothery, R. A., and Schulz, R. (2000) Circ. Res. 87 241-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]