Abstract

Copper plays a fundamental role in regulating cell growth. Many types of human cancer tissues have higher copper levels than normal tissues. Copper can also induce gene expression. However, transcription factors that mediate copper-induced cell proliferation have not been identified in mammals. Here we show that antioxidant-1 (Atox1), previously appreciated as a copper chaperone, represents a novel copper-dependent transcription factor that mediates copper-induced cell proliferation. Stimulation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with copper markedly increased cell proliferation, cyclin D1 expression, and entry into S phase, which were completely abolished in Atox1-/- MEFs. Promoter analysis and EMSA revealed that copper stimulates the Atox1 binding to a previously undescribed cis element in the cyclin D1 promoter. The ChIP assay confirms that copper stimulates Atox1 binding to the DNA in vivo. Transfection of Atox1 fused to the DNA-binding domain of Gal4 demonstrated a copper-dependent transactivation in various cell types, including endothelial and cancer cells. Furthermore, Atox1 translocated to the nucleus in response to copper through its highly conserved C-terminal KKTGK motif and N-terminal copper-binding sites. Finally, the functional role of nuclear Atox1 is demonstrated by the observation that re-expression of nuclear-targeted Atox1 in Atox1-/- MEFs rescued the defective copper-induced cell proliferation. Thus, Atox1 functions as a novel transcription factor that, when activated by copper, undergoes nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and transactivation, thereby contributing to cell proliferation.

Copper is an essential trace element in all living organisms and serves as a cofactor of key metabolic enzymes that regulate physiological processes, including cellular respiration, antioxidant defense, and iron metabolism in eukaryocytes (1–3). Accumulating evidence suggest that copper plays a fundamental role in regulating cell growth involved in physiological repair processes such as wound healing and angiogenesis as well as in various pathophysiologies including tumor growth, atherosclerosis, and neuron degenerative diseases (1–12). Of note, hyperproliferative lesions in cancer and atherosclerosis have higher copper levels in cell nuclei than normal tissues (13–15), while copper chelation prevents tumor growth and neointimal thickening after vascular injury (9–12). Furthermore, Phase I and II clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors by copper chelation showed its efficacy in disease stabilization (10, 11). These observations strongly suggest that copper plays an essential role in cell growth and proliferation; however, little is known about underlying molecular mechanisms.

Antioxidant-1 (Atox1)3 is a copper-binding protein that contains a single N-terminal copy of the conserved MXCXXC copper-binding motif, and has been appreciated as a cytosolic copper chaperone that delivers copper to the secretory compartment, which includes the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (2, 16, 17). Atox1-deficient mice failed to thrive immediately after birth, and 45% of pups died before weaning. Surviving animals exhibited growth failure (18). Recently, we found that Atox1 is expressed in the nucleus in the intimal lesions of atherosclerosis, which contain highly proliferating cells (19). Of note, Atox1 protein has the conserved lysine-rich region (KKTGK) at its C terminus, which may represent the nuclear localization signal (20).

We thus performed the present study to test the hypothesis that nuclear Atox1 may be involved in regulating copper-induced cell proliferation. Here we show that copper stimulates cell proliferation in an Atox1-dependent manner. We also demonstrate that copper induces Atox1 nuclear translocation, binding to a novel cis element of the cyclin D1 promoter and transactivation, thereby promoting cell proliferation. Moreover, we show the direct evidence that nuclear-targeted Atox1 plays an essential role in copper-stimulated cyclin D1 expression and cell proliferation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibody Production—To generate Atox1 antibody, an oligopeptide corresponding to amino acids 49–62 (DTLLATLKKTGKTV) of human Atox1 was used. The antibody was affinity-purified using the immobilized peptide. A rabbit polyclonal antiserum to Atox1 raised against purified recombinant Atox1 protein (21) was a kind gift from Dr. Diane Cox.

Immunofluorescence Studies—For immunofluorescence studies in cultured cells, cells on glass coverslips were processed as previously described (22). Briefly, after fixation in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilization in 0.2% Triton X-100, cells on coverslips were rinsed sequentially in PBS, 50 mm NH4Cl, and PBS. After incubation in blocking buffer (3% bovine serum albumin in PBS), the cells were incubated with primary antibodies, rinsed in PBS/bovine serum albumin, and incubated with the appropriate species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate or rhodamine. Cryosections and cells were examined with a Zeiss LSM 510 system, using argon and green helium/neon laser excitation lines of 488 and 543 nm with emission filters of BP 500–550 and LP 560.

Cell Culture and Nuclear Fractionation—Atox1-/- and wild-type immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum as previously described (23). Copper content in basal media was 158 nm as measured by ICP-MS. Experiments were performed in medium containing 1% serum with no additives. Human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) were purchased from VEC Technologies, Inc. (Rensselaer, NY) and were grown in endothelial cell growth medium (EGMMV, Clonetics) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All other cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS. Before stimulation, cells were serum-starved for 24 h. Nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation of MEFs was performed using an NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell Cycle Analysis—Wild-type and Atox1-/- cells in growth phase were synchronized by exposing the culture to FBS-deprived basal medium for 24 h. Quiescent cells were stimulated by the addition of 1% FBS with either 10 μm CuCl2 or 200 μm BCS for 24 h. Cells were harvested, fixed, and stained with propidium iodide using the BD Cycle TEST™PLUS Reagent kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSort (Becton-Dickinson).

Quantitative Real-time PCR—Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy mini kit and an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen). 2 μg of RNA were reverse-transcribed using the RETROscript kit (Ambion) as described by the manufacturer, using random hexamers as primer. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using the Light Cycler thermocycler (Roche Applied Science). The 10-μl reaction mixtures contained 0.3 mmol/liter of forward and reverse primers for cyclin D1 (5′-CTGGCCATGAACTACCTGGA-3′ and 5′-ATCCGCCTCTGGCATTTTGG-3′) or for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (5′-TTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC-3′ and 5′-GGCATGGACTGTG GTCATGA-3′), 50 mmol/liter KCl, 250 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 200 μmol/liter dNTPs, 1:84,000 SYBR Green I, and 0.05 units/μl TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Amplification conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 60 s, followed by 45 cycles at 65 °C for 10 s, 72 °C for 10 s. Cumulative fluorescence was measured at the end of the extension phase of each cycle. Product-specific amplification was confirmed by melting curve and agarose gel electrophoresis analysis. Quantification was performed at the log-linear phase of the reaction, and cycle numbers obtained at this point were plotted against a standard curve prepared with serially diluted control samples. Results were normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression levels.

Western Blot Analysis—Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (19). The primary antibodies used included a monoclonal antibody against human cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and two kinds of rabbit polyclonal antisera to Atox1. For Atox1 detection, samples were separated on 16.5% Tricine-SDS/PAGE gels (Bio-Rad). Equal loading of proteins was confirmed by Ponceau staining.

Plasmids, Deletions, and Site-directed Mutagenesis—The promoter-reporter constructs consist of 5′ regions of the cyclin D1 promoter inserted into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic (pGL3-Cyclin D1–962/134). Other expression promoter-reporter constructs (-735/104, -585/104, -495/104) were generated by PCR and subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega).

For immunofluorescence studies in cultured mouse fibroblasts, the Atox1 coding region was amplified by PCR and subcloned in-frame into pcDNA 3.0 with a Flag tag. The various mutants of Flag-tagged Atox1 (Flag-Atox1-ΔCT, Flag-Atox1-K56,60E, and Flag-Atox1-C12,15S) were generated by the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

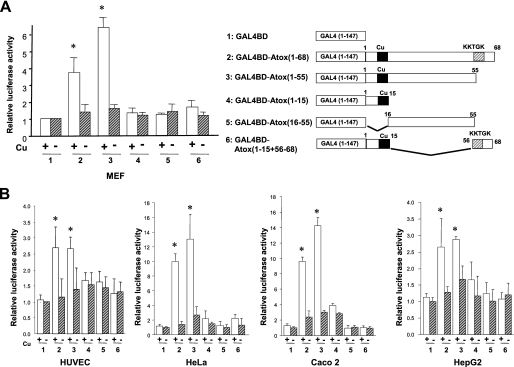

To map the transactivation domain of Atox1, we used Atox1 fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain and a luciferase-reporter plasmid containing the Gal4-binding sites. Each Atox1 mutant as described in Fig. 5A were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pM-GAL4 DBD.

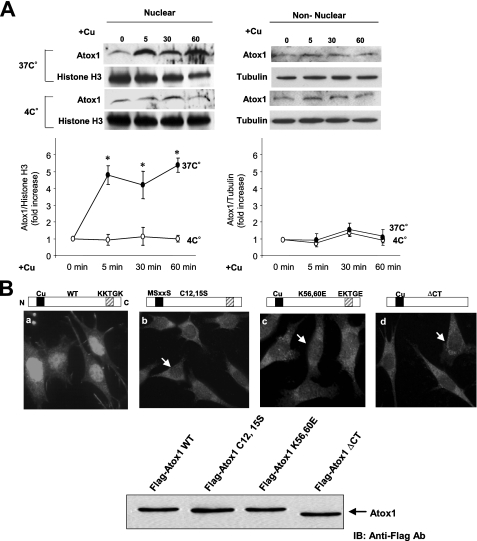

FIGURE 5.

Copper stimulates nuclear translocation of Atox1. A, copper-induced nuclear translocation of Atox1 is an active process. MEFs were stimulated with copper (10 μm) at either 37 °C or 4 °C for 1–60 min. The nuclear extract (left panel) and non-nuclear fraction (right panel) were subjected to Western blotting with anti-Atox1, anti-histone H3 (a marker for nuclear fraction), or anti-tubulin (a marker for cytosolic fraction). The fold change in Atox1 protein levels is normalized to histone-H3 or tubulin as a loading control for each fraction. The bottom panel shows the mean ± S.E. for four separate experiments (*, p < 0.01 versus control cells). B, identification of the region responsible for the nuclear localization of Atox1. Atox1-/- MEFs were transiently transfected with pcDNA containing wild-type, truncated, or mutant forms of Atox1 with the Flag tag. After transfection, cells were cultured for 12 h in the presence of CuCl2 (10 μm). Immunofluorescence was performed using a Flag-M2 antibody followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Arrow shows the absence of Atox1 in the nucleus. Immunoblotting was performed using a Flag-M2 antibody. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were loaded in each lane.

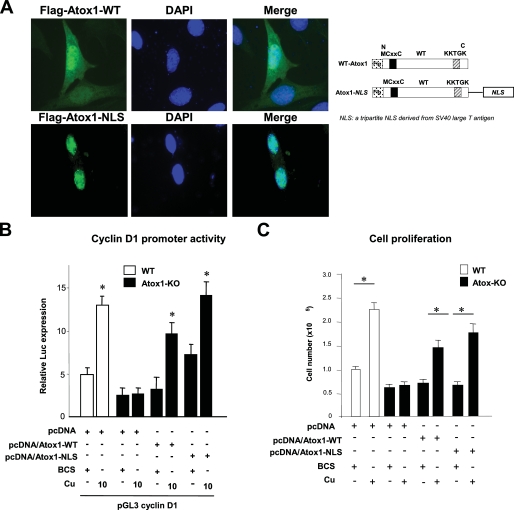

For nuclear-targeted Atox1 (Flag-Atox1-NLS) constructs, a tripartite NLS sequence (PKKKRKVD) derived from the SV40 large T antigen was fused to the C terminus of Flag-tagged WT-Atox1 (24, 25).

For the production of recombinant Atox1 protein, its coding region was ligated into the pGEX-4T-1 expression vector (Amersham Biosciences) and used to transform Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3). Site-directed mutagenesis of Atox1 cDNA was performed as mentioned above. Amplification and purification of proteins were performed as previously described (16). In all cases, the fidelity of the cDNA sequence as well as the presence of the intended mutations were confirmed by dideoxy nucleotide sequencing.

Transient Transfection and Reporter Assay—Transfection assays were carried out using the Polyfect reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The pGL3-cyclin D1 constructs were transfected into cells along with pRL-TK (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Two days after transfection, luciferase activity was assayed using a luminometer and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity produced by the co-transfected control plasmid pRL-CMV. Results shown are means ± S.E. from at least three independent transfection experiments, each performed in quadruplicate.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)—DNA-protein binding assays were carried out with nuclear extracts from mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared using NE-PER nuclear extraction reagent (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's directions. Synthetic complementary oligonucleotides were 3′-biotinylated using biotin 3′-end DNA labeling kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After labeling, complementary strands were mixed together in equimolar ratio and allowed to anneal for 1 h at 37 °C to form the double-stranded probe. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used were: 5′-GTCCTTGCATGCTAAATTAGTTCTTGCAAT-3′ (probe1 -585/-556), 5′-TTCTTGCAATTTACACGTGTTAATGAAAAT-3′ (probe2 -565/-536), 5′-TAATGAAAATGAAAGAAGATGCAGTCGCTG-3′ (probe3 -545/-516), and 5′-GCAGTCGCTGAGATTCTTTGGCCGTCTGTC-3′ (probe4 -525/-496). For competition experiments, 5′-TAATGAAAATGAAAGAAGATGCAGTCGCTG-3′ (probe3 -545/-516) or 5′-TAATGAAAATTCCCTCAGATGCAGTCGCTG-3′ (probe3 -545/-516 with mutation of -535/-530) were used. Binding reactions were carried out for 20 min at room temperature in the presence of 50 ng/μl poly(dI-dC), 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EDTA, and 2.5% glycerol in 1× binding buffer (LightShiftTM chemiluminescent EMSA kit, Pierce) using 20 fmol of biotin end-labeled target DNA and 10 μg of nuclear extract. Unlabeled target DNA (1 pmol or 2 pmol) or 1 μl of Atox1 antibody was added per 20 μl of binding reaction. Reaction mixtures were loaded onto native 4% polyacrylamide gels pre-electrophoresed for 30 min in 0.5× Tris borate/EDTA, and electrophoresed at 100 V before being transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (HybondTM-N+). Transferred DNAs were cross-linked to the membrane at 120 mJ/cm2 and detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (LightShift™ chemiluminescent EMSA kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Either nuclear extracts from MEFs, purified GST-Atox1, or GST alone were incubated with biotinylated cyclin D1 promoter fragment in the presence of CuCl2 or BCS. Identification of the nuclear protein bound to the probe was performed by preincubating nuclear extracts for 30 min with specific Atox1 antibody or with preimmune rabbit serum. Competition was performed in the presence of 50- or 100-fold molar excess of the unlabeled cyclin D1 promoter fragments or mutated promoter fragments.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay (ChIP)—Identical numbers of cells were allowed to adhere onto tissue culture plates in basal medium. After 18 h, cells were incubated in the presence of 200 μm BCS or 10 μm CuCl2. ChIP assays were performed by following the Upstate Biotechnology ChIP assay kit protocol. Cells were treated with formaldehyde (final concentration of 1%) for 15 min at 37 °C to cross-link proteins to DNA before harvesting. Then cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitor, scraped into conical tubes, and pelleted for 4 min at 2000 rpm at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended in 150 μl of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris, pH 8.1, containing protease inhibitor) and incubated for 10 min on ice. Resuspended cells were sonicated four times for 10 s each on ice. After centrifugation, the supernatant was diluted 1:10 with dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mm EDTA, 16.7 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 167 mm NaCl). The cell lysate was precleared by incubation at 4 °C for 1 h with 45 μl of salmon sperm DNA/protein A-agarose beads. The cleared lysates were incubated with anti-Atox1 antibody or normal rabbit IgG overnight. Immunoprecipitated complexes were collected by adding 45 μl of salmon sperm DNA/protein A-agarose beads for 1 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitates were washed once with low salt immune complex wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 150 mm NaCl), once with high salt immune complex wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 500 mm NaCl), and once in LiCl immune complex wash buffer (250 mm LiCl, 1% IGEPAL-CA630, 1% deoxycholic acid, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris, pH 8.1). Then immunoprecipitates were washed twice with TE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0) and extracted two times with 50 μl of 1% SDS and 0.1 m NaHCO3. Eluates were pooled and heated at 65 °C for 6 h to reverse the formaldehyde cross-linking. Then 2 μl of 0.5 m EDTA, 4 μl of 1 m Tris-HCl, pH 6.5, and 0.6 μl of 6 mg/ml proteinase K were added to the eluates, followed by incubation for 1 h at 45 °C. DNA fragments were purified with the PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Specific sequences of cyclin D1 promoter in the immunoprecipitates were detected by PCR. The following primers were used to amplify a 100-bp region of the cyclin D1 promoter: 5′-GCTAAATTAGTTCTTGCATT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CACGAGGGCACCCACGGGCG-3′ (antisense).

Kinetics Study of Nuclear Localization of Atox1—MEFs were first stimulated with 10 μm CuCl2. They were then incubated at 37 °C for 5–60 min or incubated at 37 °C for 1 min and then switched to cold medium containing the same concentration of 10 μm CuCl2 for 5–60 min. The nuclear and the non-nuclear fractions were then isolated and subjected to Western blotting with anti-Atox1 antibody. The same membranes were also probed with anti-tubulin (for the non-nuclear fraction) or anti-histone H3 (for the nuclear fraction) as a loading control.

Statistical Analysis—All data are expressed as mean ± S.E. Comparisons were made by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

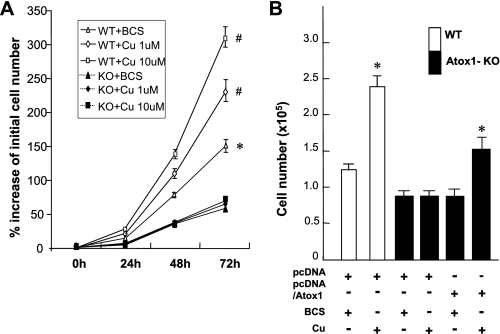

Copper-induced Cell Proliferation Requires Atox1—Stimulation of MEFs with copper at physiological concentrations markedly increased cell numbers in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and supplemental Table S1). This copper-induced cell proliferation was significantly inhibited in Atox1-/- MEFs (Fig. 1A) as well as by siRNA knockdown of Atox1 in wild-type (WT) MEFs (supplemental Fig. S1A). Re-expression of WT-human Atox1 in Atox1-/- cells rescued the effect of copper on cell proliferation (Fig. 1B). In contrast, iron, zinc, and silver (which is an electronic analogue of Cu(I) (26, 27)) had marginal effects on cell proliferation (supplemental Fig. S2). Furthermore, addition of copper in Atox1-/- cells rescued specific activities of secretory copper enzyme ceruloplasmin (Cp), which is expressed in multiple extrahepatic tissues and cells including MEFs in addition to liver (28, 29). This result suggests that copper addition in the cells lacking Atox1 bypassed the copper chaperone activity of Atox1 (i.e. copper delivery to Cp through ATP7A protein), and thus activated Cp (supplemental Fig. S3). These findings indicate that copper-induced cell proliferation requires Atox1, but it is independent of its chaperone activity. Of note, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-SOD and PEG-catalase at concentrations which block growth factor- and agonist-induced ROS production (30, 31) had no effect on copper-induced cell proliferation (data not shown), suggesting that reactive oxygen species are not involved in this response.

FIGURE 1.

Copper-induced cell proliferation requires Atox1. A, copper-induced cell proliferation in wild-type and Atox1-/- MEFs. Cells (1.5 × 103 cells/cm2) were serum-starved for 24 h and treated with either the copper chelator BCS (200 μm) or CuCl2 at the dose indicated for 72 h at 37 °C. The time of addition was considered as the t = 0 h of the experiments. Cell numbers were counted at 1-day intervals using a hemocytometer and expressed as % of initial cell number at 0 h. The data are shown as mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments. *, p < 0.01; #, p < 0.001 versus Atox1-/- cells. B, effect of copper on cell proliferation in Atox1-/- cells re-expressed with Atox1. Cell numbers were counted 72 h after transfection with either pcDNA/Atox1 or its empty vector (pcDNA) in the presence of either CuCl2 (10 μm) or BCS (200 μm). Data are the mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments. *, p < 0.01.

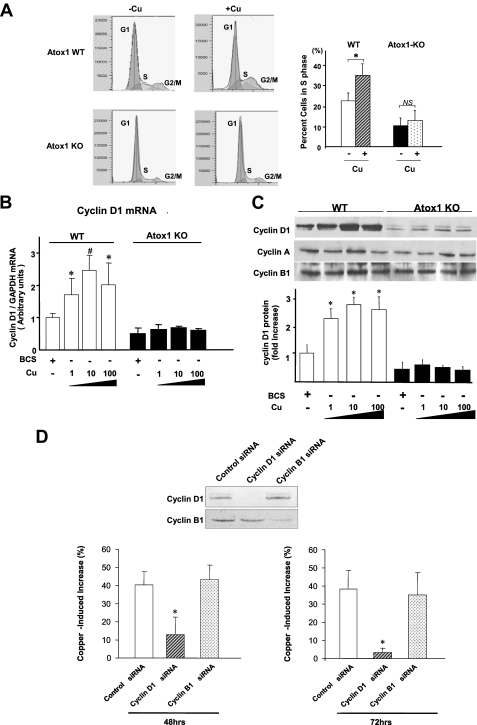

Copper Stimulates Cell Proliferation by Increasing Cyclin D1 Expression through Atox1—To determine the mechanism by which Atox1 is involved in copper-stimulated cell proliferation, we performed cell cycle analysis. We found that copper treatment in WT cells significantly increased cell numbers in the S phase from 22 ± 3% to 34 ± 4%, an effect, which was absent in Atox1-/- cells (Fig. 2A). To determine the downstream target genes of Atox1 involved in cell cycle progression, we performed gene expression analysis in WT and Atox1-/- MEFs. We found that the mRNA level of cyclin D1, a key regulator of G1-S progression (32), was dramatically down-regulated in Atox1-/- cells compared with WT cells, which was further confirmed by real-time PCR (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, copper treatment markedly increased mRNA levels of cyclin D1 in a dose-dependent manner in WT cells, but not in Atox1-/- MEFs (Fig. 2B). We also confirmed that copper stimulation up-regulated cyclin D1 protein expression, a response which was abolished in Atox1-/- MEFs (Fig. 2C), as well as by siRNA knockdown of Atox1 in WT cells (supplemental Fig. S2B). Of note, this response was specific to copper, because neither zinc nor iron had any effect on cyclin D1 expression (data not shown). Moreover, this copper- and Atox1-dependent response did not occur in other cyclins such as cyclin A and cyclin B1 (Fig. 2C). Copper-induced cell proliferation was abolished by siRNA knockdown of cyclin D1, but not cyclin B1 (Fig. 2D). By contrast, in the absence of copper, the rate of proliferation was decreased by about 40% in wild-type MEFs by siRNA knockdown of either cyclin D1 or cyclin B1 (data not shown). These findings suggest that copper stimulates cell proliferation by inducing cyclin D1 expression through a mechanism dependent on Atox1.

FIGURE 2.

Copper stimulates cell proliferation by increasing cyclin D1 expression through Atox1. A, involvement of Atox1 in copper-dependent S-phase entry. Cells were treated either with BCS (200 μm) (-Cu) or Cu (10 μm) (+Cu) for 24 h. DNA synthesis was assessed by fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Copper-induced S-phase entry in WT and Atox1-KO cells is shown as the mean ± S.E. from four separate experiments (*, p < 0.01 versus BCS-treated cells; NS, not significant). B and C, effect of copper on cyclin D1 mRNA (B) and cyclin D1 (A), and B1 protein (C) levels in WT and Atox1-KO MEFs. Cells were exposed to either BCS (200 μm) or CuCl2 at the dose indicated for 12 h. *, p < 0.01; #, p < 0.001 versus BCS-treated cells. The data depict the mean ± S.E. for four separate experiments. D, effects of cyclin D1 or cyclin B1 siRNAs on copper-induced cell proliferation in wild-type MEFs. Cells were transfected with cyclin D1, cyclin B1, or control siRNAs in the presence of either CuCl2 (10 μm) or BCS (200 μm). 48 or 72 h after transfection, cell numbers were counted. Copper-induced increases in cell number were expressed as % increase over the increase in cell number in BCS-treated cells. The data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for three separate experiments (*, p < 0.01 versus control siRNA-treated cells). Lysates prepared 72 h after transfection were immunoblotted with anti-cyclin D1 or anti-cyclin B1 antibody. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

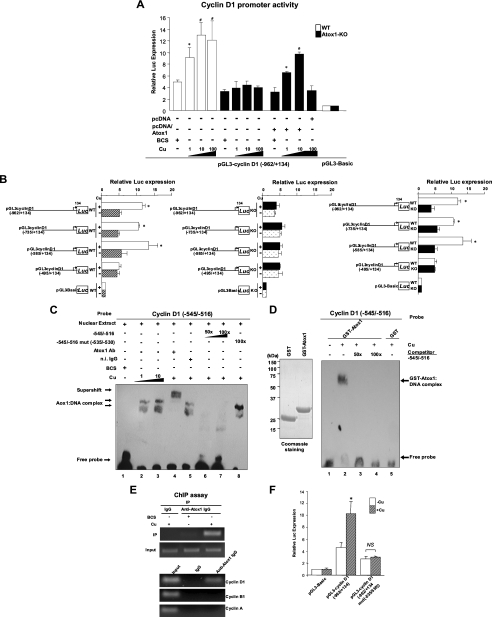

Atox1 Binds to and Activates the Cyclin D1 Promoter in a Copper-dependent Manner—We next examined whether Atox1 is involved in cyclin D1 gene expression. Luciferase reporter gene assays demonstrated that copper, but not silver, stimulated the cyclin D1 promoter in a dose-dependent manner in WT MEFs (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S4A). This response was abrogated in Atox1-/- cells and was rescued by re-expression of Atox1-WT. A 5′ deletion analysis of the cyclin D1 promoter in WT cells identified the copper-responsive region in -585/-495 (Fig. 3B, left panel). We confirmed that all of the 5′ deletion constructs of cyclin D1 promoter had no response to copper in Atox1-/- cells (Fig. 3B, middle panel), and that an Atox1-responsive region regulating cyclin D1 promoter activity resides within the copper-responsive element between -585 and -495 (Fig. 3B, right panel). To determine if nuclear proteins could specifically bind to this region, we performed EMSAs in WT cells. We found that specific DNA-protein-binding complexes were produced as a major slower migrating band only by a biotinylated cyclin D1 promoter fragment -545/-516 (Fig. 3C), but not by -585/-556, -565/-536 or -525/-496 fragments (data not shown). The DNA-protein complex formation was competed by 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled -545/-516 (Fig. 3C, lanes 6 and 7). To map the -545 to -516 binding area in greater detail, mutations which spanned the region with sequential nucleotide substitutions were created. The major DNA-protein complexes were competed by 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled mutants, except for unlabeled mutants in the region -535/-530 (Fig. 3C, lane 8), suggesting that nuclear proteins bind to the region -535 to -530 (5′-GAAAGA-3′) in the cyclin D1 promoter.

FIGURE 3.

Atox1 binds to and activates the cyclin D1 promoter in a copper-dependent manner. A, effect of copper on transactivation of the cyclin D1 gene promoter in WT and Atox1-KO MEFs. Cells were transiently transfected with cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter constructs (pGL3-cyclin D1 (-962/+134)) or empty reporter constructs (pGL3-Basic) along with either pcDNA/Atox1 or pcDNA. Cells were treated with either BCS (200 μm) or CuCl2 at the dose indicated. Two days after transfection, the luciferase activity was assayed and normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity produced by the co-transfected control plasmid pRL-CMV. Results shown are means ± S.E. from at least three independent transfection experiments, each performed in quadruplicate (*, p < 0.01; #, p < 0.001 versus BCS-treated WT cells, or BCS-treated Atox1-/- cells transfected with pcDNA/Atox1). B, identification of copper/Atox1-responsive elements in a proximal 90-bp cyclin D1 promoter element. WT and Atox1-KO MEFs were transiently transfected with 5′ deletion constructs of cyclin D1 in the presence of either CuCl2 (10 μm, +Cu) or BCS (200 μm, -Cu). Left and middle panels, relative luciferase activity in WT or Atox1-KO MEFs in the presence of either CuCl2 (10 μm, +Cu) or the copper chelator BCS (200 μm, -Cu). Right panel, relative luciferase activity in wild-type and Atox1-/- cells in the presence of CuCl2 (10 μm). Results shown are means ± S.E. from at least three independent transfection experiments, each performed in quadruplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus BCS-treated WT (left panel), or CuCl2-treated Atox1-/-cells (right panel)). C and D, EMSA, showing the binding of Atox1 to the region -535 to -530 in the cyclin D1 promoter in a copper-dependent manner. C, nuclear extracts from MEFs were incubated with the biotinylated cyclin D1 promoter fragment with indicated treatments. D, left panel shows purified GST and GST-Atox1. Right panel, purified GST or GST-Atox1 was incubated with the DNA probe with indicated treatments. E, ChIP assay showing association of Atox1 with the cyclin D1 promoter in a copper-dependent manner in vivo. Cells were treated with either indicated treatments (upper panel) or CuCl2 (10 μm) (lower panel) and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. Nuclear lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Atox1 antibody or normal IgG, and the promoter region of either cyclin D1, cyclin B1, or cyclin A was amplified by PCR. A small aliquot of lysates before IP were used for PCR amplification as the input control (Input). Results are representative of three independent experiments. F, region -535 to -530 is required for copper-induced activation of the cyclin D1 promoter. MEFs were transfected with a cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter construct (pGL3-cyclin D1 (-962/+134)) with or without mutation of the copper/Atox1-responsive element (-535 to -530 region). *, p < 0.01 versus BCS-treated cells.

To determine if it is Atox1 that binds to the region -535 to -530 in the cyclin D1 promoter, we performed supershift assays on nuclear extracts of WT MEFs. Antibody specific for Atox1, but not preimmune rabbit serum, supershifted DNA-protein complexes, suggesting that the major slower migrating band represents binding of Atox1 to the region -535 to -530 (Fig. 3C, lanes 4 and 5). Note that Atox1 binding to this region requires copper in vitro (Fig. 3C, lanes 1, 2, and 3). To test if Atox1 directly binds to the cyclin D1 promoter, we performed EMSA using recombinant GST-Atox1. The cyclin D1 promoter segment (-545/-516) directly associated with GST-Atox1, but not with GST alone. This association was dependent on copper and was competed by 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled cyclin D1 (-545/-516), but not by 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled cyclin D1 (-545/-516) with mutation of the region -535 to -530 (Fig. 3D and supplemental Fig. S5). To test whether endogenous Atox1 binds to the cyclin D1 promoter in vivo, we performed ChIP assays using Atox1 antibodies to precipitate Atox1 in WT cells treated with copper (10 μm) or with the copper chelator BCS. The promoter region of cyclin D1, but not those of cyclin B1 or cyclin A that lack Atox1-binding sites, was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts by Atox1 antibodies, but not by normal IgG, in the presence of copper (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, mutation of the GA-rich region -535 to -530 in the cyclin D1 promoter abolished copper-induced activation of the cyclin D1 promoter (Fig. 3F), suggesting that this region may act as a core element for Atox1 binding to target DNA. These findings indicate that Atox1 binds to the cyclin D1 promoter at -535 to -530 that is essential for the copper-dependent expression of cyclin D1.

Copper Stimulates Transactivation Activity of Atox1—We next examined whether Atox1 exhibits transactivation activity. Analysis using various mutants of Atox1 fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (which contains its own nuclear localizing domain, Ref. 33) in MEFs revealed that the Gal4/WT Atox1 (residues 1–68) and the Gal4/Atox1-ΔCT (residues 1–55) markedly activated the transcription of a reporter gene (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the GAL4/Atox1 (residues 1–15), Atox1 (residues 16–55), or an internally deleted Atox1 (Δ16–55) did not activate it. Atox1 transactivation was observed in all five cell lines that we tested (Fig. 4B). Note that transactivation activity of Atox1 required copper, while silver had no effect on transactivation of Atox1 (supplemental Fig. S4B). These findings indicate that Atox1 functions as a copper-dependent DNA-binding transcription factor to induce cyclin D1, which depends on its residues 1–55.

FIGURE 4.

Copper stimulates transactivation activity of Atox1. Activation of gene expression by Atox1 in MEFs (A) and other cell types (B). Different GAL4-Atox1 hybrid constructs were cotransfected into the indicated cells along with the luciferase reporter vector containing GAL4-binding sites in the presence of either CuCl2 (10 μm, +Cu) or BCS (200 μm, -Cu). Results shown are means ± S.E. from at least three independent transfection experiments, each performed in quadruplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus BCS-treated cells).

Copper Stimulates Nuclear Translocation of Atox1—To examine whether nuclear localization of Atox1 is copper-dependent, we performed biochemical cell fractionation and immunofluorescence analysis. Cell fractionation analysis revealed that copper treatment of WT MEFs rapidly promoted translocation of Atox1 to the nucleus within 5 min, peaking at about 60 min (Fig. 5A, left top and supplemental Fig. S6A). Copper-induced nuclear translocation of Atox1 was completely abolished in the cold medium (Fig. 5A, left bottom), suggesting that it is an active process. In contrast, the level of Atox1 in the non-nuclear fraction remained unchanged (Fig. 5A, right) or slightly decreased (supplemental Fig. S6B) during this time period. To further confirm this result, we performed Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis in Atox1-/- MEFs transfected with Flag-Atox1-WT cDNA in the presence and absence of copper. Western blot analysis in nuclear and non-nuclear fractions showed that Flag-Atox1 expression in the nuclear fraction was very low in the absence of copper, was markedly increased in the nuclear fraction, and significantly decreased in the non-nuclear fraction in response to copper (supplemental Fig. S6, C and D). In contrast, immunofluorescence analysis in Atox1-/- MEFs transfected with various mutant Atox1 constructs revealed that copper-induced nuclear translocation of Atox1 depends on its C-terminal highly conserved 56KKTGK60 motif and its conserved copper-binding sites Cys-12/Cys-15 (Fig. 5B). Of note, total protein levels of Atox1 mutants are not different from those of Atox1-WT (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, re-expression of Atox1-WT, but not Atox1 mutants in which its nuclear localization is blocked, rescued the copper-stimulated cyclin D1 promoter activity and cell proliferation in Atox1-/- MEFs (supplemental Fig. S7). Moreover, EMSAs using GST-tagged Atox1 protein showed that the cyclin D1 promoter segment (-545/-516) directly bound to GST-Atox1-WT, but not to either GST alone or to GST-Atox1 mutants (supplemental Fig. S5). These findings further support our conclusion that Atox1 functions as a copper-dependent transcription factor to regulate cyclin D1 promoter activity, thereby promoting cell proliferation.

Nuclear Atox1 Is Essential for Copper-induced Cell Proliferation—To determine specifically the function of nuclear Atox1, we examined the effect of re-expression of nuclear-targeted Atox1 (Atox1-NLS) on cyclin D1 promoter activity and cell proliferation in Atox1-/- MEFs (Fig. 6). We confirmed that Atox1-NLS protein was expressed exclusively in the nucleus (Fig. 6A). Both Atox1-NLS and Atox1-WT increased cell proliferation as well as cyclin D1 promoter activity (Fig. 6, B and C). These findings suggest that nuclear Atox1 functions as a copper-dependent transcription factor to increase cyclin D1 promoter activity, thereby promoting cell proliferation.

FIGURE 6.

Nuclear Atox1 is essential for copper-induced cell proliferation. A, right panel, generation of subcellular targeting Atox1 fusion constructs. Nuclear-targeted Atox1 (Flag-Atox1-NLS) was created by fusing a tripartite NLS sequence derived from SV40 large T antigen (NLS) to the C terminus of Flag-tagged WT-Atox1 (24, 25). Left panel, subcellular localization of Atox1-WT and Atox1-NLS fusion proteins. Atox1-/- mouse fibroblasts were transfected with Flag-Atox1-WT or Flag-Atox1 mutants, immunolabeled with antibodies for Flag tag (left panels, green) and nuclear marker, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (middle panel, blue). Upper panel, WT Atox1 was found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Lower panel, Atox1-NLS was mainly localized at the nucleus. B, effect of re-expression of Atox1-WT and Atox1-NLS on transactivation of the cyclin D1 promoter in Atox1-/- MEFs. Cells were transiently transfected with cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter constructs along with Atox1-WT or Atox1-NLS in the presence of either BCS (200 μm) or CuCl2 at the dose indicated. Bars are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent transfection experiments, each performed in quadruplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus BCS-treated wild-type cells or BCS-treated Atox1-/- cells transfected with pcDNA). C, effect of re-expression of Atox1-WT or Atox1-NLS on cell proliferation in Atox1-/- MEFs. Atox1-/- MEFs were transfected with Atox1-WT or Atox1-NLS in the presence of either CuCl2 (10 μm) or BCS (200 μm). 72 h after transfection, cell numbers were counted. The data are the means ± S.E. from three separate experiments. (*, p < 0.01 versus BCS-treated WT cells or Atox1-/- cells transfected with either pcDNA/Atox1-WT or pcDNA/Atox1-NLS).

DISCUSSION

Copper has been shown to stimulate cell proliferation; however, underlying mechanisms have not been demonstrated. The present study provides the first evidence that Atox1 functions as a novel transcription factor that, when activated by copper, undergoes nuclear translocation, binding to the novel cis element of the cyclin D1 promoter, and transactivation, thereby mediating effects of copper on cell proliferation.

The present study demonstrates that nuclear translocation of Atox1 is copper-dependent. We previously reported that Atox1 is expressed in the nucleus in the intimal lesions of atherosclerosis, which contain highly proliferating cells (19). Furthermore, higher levels of copper are located in the nuclei in highly proliferating tumors, whereas copper is located predominantly within the cytoplasm in normal tissue (13–15). In addition, nuclear accumulation of copper is strongly associated with proliferation of hepatocytes in Atp7b-/- mice, an animal model of Wilson disease (34). Thus, nuclear Atox1 may be positively correlated with the proliferation status of cells. In contrast, the yeast homolog of Atox1 localizes exclusively in the cytosol (17). This may suggest that mammalian Atox1 might have acquired nuclear function in addition to its copper chaperone function for the secretory compartment during the course of evolution.

The present study with re-expression of nuclear-targeted Atox1 in Atox1-/- cells strongly suggests that it is nuclear Atox1 that plays an essential role in copper-stimulated increases in cyclin D1 expression and cell proliferation. To protect cells from copper toxicity, cells extraordinarily restrict the level of intracellular free copper by a wide variety of copper detoxification systems such as metallothioneins (35, 36). Thus, genetic studies in yeast and mammals have shown that Atox1 in the cytoplasm functions as a copper chaperone to shuttle cytosolic copper to the secretory pathway for the copper loading of secretory copper enzymes such as lysyl oxidase (18), ceruloplasmin, and extracellular superoxide dismutase (19). This is for their full activation via the copper transporters ATP7A or ATP7B at the trans-Golgi network (2, 16, 17). Taken together with the results of our study, Atox1 may coordinate both nuclear transcription factor and cytosolic copper chaperone functions, thereby orchestrating the complex events of cell growth and assembly of tissue architecture, including extracellular matrix, in physiological and pathophysiological settings in multicellular organisms. It has been shown that tumor cell growth and neovascularization during ischemia, which depend on copper (9, 11), involve cell proliferation, interaction of cells with extracellular matrix, and appropriate redox states (37, 38). Thus, nuclear Atox1 may sense the presence of copper for cell proliferation, whereas non-nuclear Atox1 may play a role in the assembly of extracellular matrix and controlling the redox state by regulating activities of secretory copper enzymes.

Our findings indicate that copper regulates the nuclear function of Atox1 at multiple steps: nuclear transport, DNA binding, and transcriptional activity. There are several possible mechanisms for this copper-dependent modulation of Atox1 function. The 1H NMR solution structure of Atox1 demonstrated that copper binding to Atox1 through its two conserved cysteine residues promotes a conformational change in its basic patch (39). The 1.8-A resolution x-ray crystal structure of Atox1 revealed that arginine (Arg-21) and a number of conserved lysines, including Lys-56 and Lys-60, generate a positively charged patch located on or near its two α-helices, which is proposed to dock to a negatively charged surface of the Menkes protein (40). These structural considerations suggest that copper binding to Atox1 may induce conformational changes in the basic patch of Atox1, thereby facilitating Atox1 binding to negatively charged DNA. This copper-induced conformational change of Atox1 also appears to be essential to its transactivation and nuclear translocation. Indeed, we found that either mutation or truncation of the copper-binding domain of Atox1 completely blocks both transcriptional activation and nuclear translocation. Mutation of conserved lysines (Lys-56 and Lys-60) in the basic patch of Atox1 also prevents its nuclear translocation.

Copper is absolutely required for aerobic life and yet, paradoxically, is highly toxic. Thus, it is essential that copper is maintained at a level sufficient for, but not toxic to, cell growth. Given that copper tightly regulates the transcriptional function of Atox1, it is intriguing to speculate that Atox1 may function as sensors of intracellular copper concentrations, thereby regulating various copper-mediated biological effects such as cell proliferation, angiogenesis, hemoglobin synthesis, nerve myelination, endorphin action, extracellular matrix stabilization, leukocyte differentiation, and neutrophils and granulocyte maturation (3, 41, 42). In yeast, copper homeostasis is mediated by copper-responsive transcription factors such as Ace1 and Mac1 that regulate expression of genes involved in copper ion uptake, copper sequestration, and defense against reactive oxygen intermediates (43). However, mammalian genomes do not contain the ortholog of Ace1 and Mac1, and a functional homolog has not been identified thus far.

In conclusion, we uncovered a novel function of Atox1 as a transcription factor that translates copper availability into gene expression and cell proliferation. This nuclear function of Atox1 may contribute to hyperproliferative conditions such as cancer, angiogenesis, and atherosclerosis. As Atox1 seems to be regulated at multiple steps, such as nuclear transport, DNA binding, and transcriptional activity, each of the steps represents a potential point of intervention to modulate its function. Copper deficiency therapies prevent tumor progression in clinical trials (44, 45). Atox1 might contribute to this beneficial effect of anti-copper therapy. Thus, these findings provide insight into Atox1 as a novel potential therapeutic target for copper-dependent hyperproliferative disorders such as cancer and atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jonathan Gitlin of Washington University in St. Louis for his gift of plasmid pcDNA-Atox1 and immortalized Atox1-/- and Atox1+/+ cells, Dr. David Harrison (Emory University, Atlanta) for helpful discussions, and Dr. Hideko Kasahara (University of Florida, Gainesville) for technical help. We also thank Dr. Bibuendra Sarkar, Dr. Steven Moore, and Dr. Diane W. Cox (University of Alberta, Canada) for the gift of antibody to Atox1, and Drs. F. McCormick, O. Tetsu (University of California, San Francisco), A. Arnold, and R. Pestell (Albert Einstein Cancer Center, New York) for the gift of cyclin D1 promoter-reporter constructs.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL70187 (to T. F.), P01 HL58000 (to T. F.), and American Heart Association Grant-In-aid 0455242B (to T. F.), R01 HL 077524 (to M. U.-F.), and American Heart Association Grant-in-aid 0555308B and 0755805Z (to M.U.-F.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7 and Table S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Atox1, antioxidant-1; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; FBS, fetal bovine serum; Tricine, N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine; GST, glutathione S-transferase; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation assay; WT, wild type; BCS, bathocuproine disulfonic acid; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; NLS, nuclear localization signal.

References

- 1.Pena, M. M., Lee, J., and Thiele, D. J. (1999) J. Nutr. 129 1251-1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Culotta, V. C., and Gitlin, J. D. (2001) in Molecular and Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease (Scriver, C. R., Beaudet, A. L., Sly, W. S., and Vale, D., eds) pp. 3105-3126, McGraw-Hill, New York

- 3.Linder, M. C. (1991) in Biochemistry of Copper (Linder, M. C., ed) pp. 1-13, Plenum Press, New York

- 4.Hu, G. F. (1998) J. Cell. Biochem. 69 326-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAuslan, B. R., and Gole, G. A. (1980) Trans. Ophthalmol Soc. UK 100 354-358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volker, W., Dorszewski, A., Unruh, V., Robenek, H., Breithardt, G., and Buddecke, E. (1997) Atherosclerosis 130 29-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen, C. K., Khanna, S., Venojarvi, M., Trikha, P., Ellison, E. C., Hunt, T. K., and Roy, S. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282 H1821-H1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkaya, B., and Aletta, J. M. (2005) J. Neurobiol. 63 49-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman, V. L., Brewer, G. J., and Merajver, S. D. (2004) Endocr. Relat. Cancer 11 255-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer, G. J. (2005) Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 5 195-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris, E. D. (2004) Nutr. Rev. 62 60-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandinov, L., Mandinova, A., Kyurkchiev, S., Kyurkchiev, D., Kehayov, I., Kolev, V., Soldi, R., Bagala, C., de Muinck, E. D., Lindner, V., Post, M. J., Simons, M., Bellum, S., Prudovsky, I., and Maciag, T. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 6700-6705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold, M., and Sasse, D. (1961) Cancer Res. 21 761-766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs, A. G., and de Lustig, E. S. (1989) Oncology 46 183-187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniel, K. G., Harbach, R. H., Guida, W. C., and Dou, Q. P. (2004) Front Biosci. 9 2652-2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung, I. H., Casareno, R. L., Labesse, G., Mathews, F. S., and Gitlin, J. D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 1749-1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin, S. J., Pufahl, R. A., Dancis, A., O'Halloran, T. V., and Culotta, V. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 9215-9220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamza, I., Faisst, A., Prohaska, J., Chen, J., Gruss, P., and Gitlin, J. D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 6848-6852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeney, V., Itoh, S., Wendt, M., Gradek, Q., Ushio-Fukai, M., Harrison, D. G., and Fukai, T. (2005) Circ. Res. 96 723-729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmeri, D., and Malim, M. H. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 1218-1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore, S. D., Helmle, K. E., Prat, L. M., and Cox, D. W. (2002) Mamm. Genome 13 563-568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ushio-Fukai, M., Griendling, K. K., Becker, P. L., Hilenski, L., Halleran, S., and Alexander, R. W. (2001) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21 489-495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamza, I., Prohaska, J., and Gitlin, J. D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 1215-1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer-Fantuzzi, L., and Vesco, C. (1988) Mol. Cell. Biol. 8 5495-5503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalderon, D., Roberts, B. L., Richardson, W. D., and Smith, A. E. (1984) Cell 39, 499-509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furst, P., Hu, S., Hackett, R., and Hamer, D. (1988) Cell 55 705-717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winge, D. R., Nielson, K. B., Gray, W. R., and Hamer, D. H. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260 14464-14470 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu, F. F., and Olden, K. (1985) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 126 15-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellman, N. E., and Gitlin, J. D. (2002) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 22 439-458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ushio-Fukai, M., Tang, Y., Fukai, T., Dikalov, S. I., Ma, Y., Fujimoto, M., Quinn, M. T., Pagano, P. J., Johnson, C., and Alexander, R. W. (2002) Circ. Res. 91 1160-1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushio-Fukai, M., Alexander, R. W., Akers, M., and Griendling, K. K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 15022-15029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu, M., Wang, C., Li, Z., Sakamaki, T., and Pestell, R. G. (2004) Endocrinology 145 5439-5447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan, C. K., Hubner, S., Hu, W., and Jans, D. A. (1998) Gene Ther. 5 1204-1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huster, D., Finegold, M. J., Morgan, C. T., Burkhead, J. L., Nixon, R., Vanderwerf, S. M., Gilliam, C. T., and Lutsenko, S. (2006) Am. J. Pathol. 168 423-434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rae, T. D., Schmidt, P. J., Pufahl, R. A., Culotta, V. C., and O'Halloran, T. V. (1999) Science 284 805-808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Halloran, T. V., and Culotta, V. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 25057-25060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim, H. W., Lin, A., Guldberg, R. E., Ushio-Fukai, M., and Fukai, T. (2007) Circ. Res. 101 409-419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payne, S. L., Fogelgren, B., Hess, A. R., Seftor, E. A., Wiley, E. L., Fong, S. F., Csiszar, K., Hendrix, M. J., and Kirschmann, D. A. (2005) Cancer Res. 65 11429-11436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenzweig, A. C. (2001) Acc. Chem. Res. 34 119-128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wernimont, A. K., Huffman, D. L., Lamb, A. L., O'Halloran, T. V., and Rosenzweig, A. C. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 766-771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Percival, S. S. (1998) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67 Suppl. 5, 1064S-1068S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rucker, R. B., Kosonen, T., Clegg, M. S., Mitchell, A. E., Rucker, B. R., Uriu-Hare, J. Y., and Keen, C. L. (1998) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67 Suppl. 5, 996S-1002S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winge, D. R., Graden, J. A., Posewitz, M. C., Martins, L. J., Jensen, L. T., and Simon, J. R. (1997) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2 2-10 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brewer, G. J., Dick, R. D., Grover, D. K., LeClaire, V., Tseng, M., Wicha, M., Pienta, K., Redman, B. G., Jahan, T., Sondak, V. K., Strawderman, M., LeCarpentier, G., and Merajver, S. D. (2000) Clin. Cancer Res. 6 1-10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redman, B. G., Esper, P., Pan, Q., Dunn, R. L., Hussain, H. K., Chenevert, T., Brewer, G. J., and Merajver, S. D. (2003) Clin. Cancer Res. 9 1666-1672 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.