SYNOPSIS

The Institute of Medicine has issued numerous reports calling for the public health workforce to be adept in policy-making, communication, science translation, and other advocacy skills. Public health competencies include advocacy capabilities, but few public health graduate institutions provide systematic training for translating public health science into policy action. Specialized health-advocacy training is needed to provide future leaders with policy-making knowledge and skills in generating public support, policy-maker communications, and policy campaign operations that could lead to improvements in the outcomes of public health initiatives. Advocacy training should draw on nonprofit and government practitioners who have a range of advocacy experiences and skills. This article describes a potential model curriculum for introductory health-advocacy theory and skills based on the course, Health Advocacy, a winner of the Delta Omega Innovative Public Health Curriculum Award, at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland.

Public health professionals work to advance laws, policies, and programs that prevent disease and protect the public's health. For instance, scientists with specific expertise and relevant research knowledge translate scientific or technical information for policy makers. Nongovernmental health staff run multifaceted advocacy campaigns that rely on communications, policy analysis, and grassroots partnerships to encourage health-policy changes. Government health officials are called on to explain their agency's budget needs. In every instance, advocacy skills are essential.

THE GAP BETWEEN PUBLIC HEALTH ACADEMIA AND PRACTICE

The 1988 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report The Future of Public Health identified the core functions of public health agencies at all levels of government as assessment, policy development, and assurance.1 The IOM recommended that “every public health agency exercises its responsibility to serve the public interest in the development of comprehensive public health policies by promoting the use of the scientific knowledge base in decision-making about public health and by leading in developing public health policies. Agencies must take a strategic approach, developed on the basis of a positive appreciation for the democratic political process.”1 The follow-up IOM report in 2002 built on these findings by noting the need for greater political will to advance the field.2

The IOM's 2003 report, Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century, noted the dearth of public health professionals competent in policy development or advocacy.3 In its recommendations for improving public health professional training, the IOM highlighted the need for enhanced policy training:

Although the importance of policy has long been recognized, education in policy at many schools of public health is currently minimal. Education in policy analysis, policy development, and the application of policy must be addressed. Should schools wish to be significant players in the future of public health and health care, dwelling on the science of public health without paying appropriate attention to both politics and policy will not be enough.3

Other organizations have similarly worked to develop the policy-advocacy competency skills of the public health workforce in areas such as communicating with policy makers or interpreting laws, regulations, or policies related to public health.4

Still, few public health students are prepared as health advocates, and most graduate with minimal training in policy and media advocacy,5 although several advocacy education initiatives are underway. Schools of public health at Boston University in Boston, Massachusetts, the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona, the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in Piscataway, New Jersey, George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, all have offered a health-advocacy course in the past year, but none has required the course for degree completion. Apart from accredited public health institutions, Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York, offers the country's only graduate degree (a master of arts) in health advocacy, designed to train professionals to improve health care and access. In addition, the Berkeley Media Studies Group in Berkeley, California, with support from the California Endowment, is producing a curriculum guide for teaching advocacy.6

While U.S. public health schools and programs have a rich tradition of teaching research methods and sociobehavioral interventions, there is a general void in the systematic teaching of advocacy and the related skills necessary for translating science into public policy.6 Our academic public health institutions should establish training courses that prepare scientists and health professionals who are competent in translating public health evidence into health-policy action.7

One model for providing advocacy knowledge and related skill sets is the Health Advocacy course at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH) in Baltimore, Maryland. The graduate-level course won the 2004 Curriculum Award from the national Delta Omega Honorary Society in Public Health for “innovative public health curriculum, which integrates practical community-based practice and scholarship into classroom discussions, applies public health principles, uses science-based decision-making, and involves the community in a teaching partnership.”8 The course was started in 1998 by JHSPH faculty members Steve Teret, Stephen Moore, and Susan DeFrancesco as a series of seminars on health-advocacy issues. It has since evolved with their guidance into a graduate course designed to provide the policy development, communication, and advocacy skills needed for health-policy action.

INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN AND INNOVATIONS FOR ADVOCACY TRAINING

The three-credit, 24-instructional-hour course is designed to prepare students from all public health disciplines to identify public health problems, analyze potential policy solutions, and determine what advocacy strategies to apply to encourage policy makers to implement the recommended public health policy solution. Currently, annual for-credit enrollment is approximately 100 students. For the main on-campus course, approximately 80% of the class participants are enrolled at JHSPH, with a relatively even distribution in most disciplines. Remaining students come from the School of Medicine (10%) and other university programs, including public health undergraduates. (Separately, the Preventive Medicine Residency program adapts the course to a one-week mandatory workshop to accommodate scheduling conflicts.) Approximately 10% of the students are enrolled in the course because of program requirements (for a master of health science in health policy).

The course's learning objectives are as follows:

Assess a public health problem and articulate the health, fiscal, administrative, legal, social, and political implications of solving the problem with policy strategies vs. behavioral education.

Analyze the public health laws, regulations, and policies related to public health problems, and identify what policy options should be targeted for advocacy efforts.

Develop plans for implementing policy campaigns, including goals, tactics, and partners.

Use the media to communicate information on advancing health policies.

Effectively present accurate demographic, statistical, programmatic, and scientific information for policy makers and lay audiences.

The course combines advocacy, policy, and communication theory with advocacy case studies and skill-building opportunities.

Advocacy construct

The course defines health advocacy as “the application of information and resources to effect systemic changes … intended to reduce the occurrence or severity of public health problems.”9 It is “a set of skills used to create a shift in public opinion and public policy, and to mobilize the necessary resources and forces to support an issue, policy, or constituency.”10 Whereas public health teaching focuses on the important theories and skills for advancing sociobehavioral change as one public health approach, this course focuses on the skills for influencing and informing health-policy improvements.

The topics covered by lectures and classroom exercises include the following:

policy-making

intervention points

understanding government health agencies and their budget processes

the role of public health advocacy in federal and state policy development and political debate

media advocacy

building coalitions to implement public health goals

laws regulating lobbying and advocacy for nonprofit organizations

working with communities to advocate for policy change

strategies and tips for preparing testimony and testifying

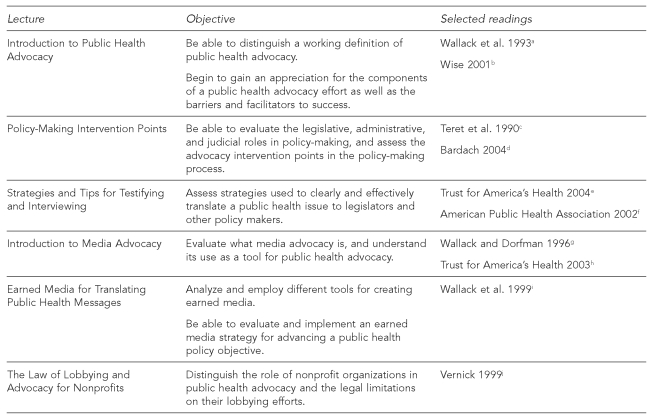

At this stage, a textbook for comprehensive health advocacy does not exist. To provide educational theory and background for class lectures and discussions, a series of articles, reports, and book excerpts are provided online to the students. Figure 1 identifies the key reading materials and their related objectives. Other reading materials, such as recent health-policy newspaper articles or advocacy reports, are also included to address timely health-policy issues and the lecturer's expertise.

Figure 1.

Key reading materials and related lectures and objectives for the Health Advocacy course at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Wallack L, Dorfman L, Jernigan D, Themba M. The advocacy connection, chapter 2. In: Media advocacy and public health: power for prevention. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications, Inc.; 1993. p. 26-51.

Wise M. The role of advocacy in promoting health. Promot Educ 2001;8:69-74.

Teret SP, Alexander GR, Bailey LA. The passage of Maryland's gun law: data and advocacy for injury prevention. J Public Health Policy 1990;11:26-38.

Bardach E. Appendix B: things governments do. In: A practical guide for policy analysis: the eightfold path to more effective problem solving, 2nd ed. Washington: CQ Press; 2004. p. 123-31.

Trust for America's Health. You, too, can be an effective health advocate: make a difference in 5 easy steps [cited 2008 Mar 4]. Available from: URL: http://healthyamericans.org/reports/files/advocacyguide.pdf

Brownson RC, Malone BR. Communicating public health information to policy makers, chapter 7. In: Nelson DE, Brownson RC, Remington PL, Parvanta C, editors. Communicating public health information effectively: a practical guide for practitioners. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2002. p. 96-114.

Wallack L, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: a strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Educ Q 1996;23:293-317.

Trust for America's Health. 5 easy steps to making health advocacy hometown news: advocating for better health in your community through media attention [cited 2008 Mar 4]. Available from: URL: http://healthyamericans.org/reports/files/mediaguide.pdf

Wallack L, Woodruff K, Dorfman L, Diaz I. News for a change: an advocate's guide to working with the media. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999.

Vernick JS. Lobbying and advocacy for the public's health: what are the limits for nonprofit organizations? Am J Public Health 1999;89:1425-9.

Real-world experiences integrated throughout the course

As emphasized in the IOM report,3 practitioners need to be better integrated into the pedagogical experience. Thus, faculty who are experienced in the health policy-making process should teach health-advocacy courses. To ensure a full perspective, guest lecturers can provide a range of advocacy experiences at the international, federal, state, and local levels in addition to advocacy by government, nonprofit, and even business interests.

Structured teaching of policy-making should draw on case studies and direct experiences. However, these case studies should not be lectures for retelling “war stories,” but rather should be designed to illustrate specific policy theory, learning objectives, and skill sets. As an example, one lecturer is the campaign manager for Save Darfur, a coalition of more than 170 faith-based, humanitarian, and health organizations advancing policy solutions and raising public awareness about the ongoing genocide in the Darfur region of Sudan. His presentation provides a captivating and insightful analysis of the campaign's goals, policy targets, media-advocacy strategy, and coalition efforts. His lecture follows the class on introduction to health-advocacy concepts, which provides context.

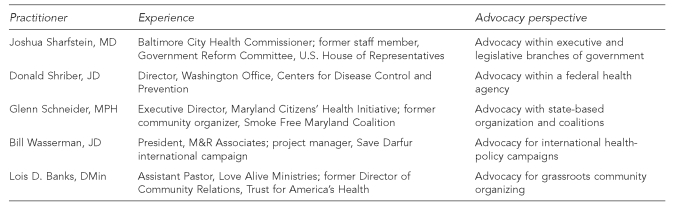

An advocacy campaign at any level, from international to local, could be used as long as the lecturer provides an analysis that parallels the conceptual framework presented in the previous class. Figure 2 provides examples of previous Health Advocacy course lecturers and their links to advocacy practice experience. For the Health Advocacy course, lecturers have followed the strategic approach of the Midwest Academy in Chicago, Illinois, which provides training for progressive organizations.

Figure 2.

Examples of lecturers and links to advocacy practice experience

MD = doctor of medicine

JD = juris doctor

MPH = master of public health

DMin = doctor of ministry

Skill development through group exercises

Class lectures are typically followed by in-class exercises to help students integrate and experience the concepts and skills needed for policy communication and action. One of the most popular exercises builds on two media-advocacy and communication lectures, which include pointers on presenting technical information to a lay audience via print, audio, or television media. In a 90-minute session, the students are divided into groups representing different constituencies, ranging from government to nonprofit organizations, concerned with a local public health issue. The exercise centers around injury control and prevention, and a fictional policy debate in a small city on how to improve playground safety in an area with high rates of crime, underfunded schools, and increasing playgroup accidents because of deteriorating and unsafe equipment. Each group is given time to develop (1) its policy position, (2) messages that frame its policy position as a public health issue, and (3) advocacy strategies to advance its proposed policy improvement.

Upon completion of the group work, a mock television reporter unexpectedly appears before the class with a microphone and video film crew, announcing a “live” story concerning a child killed in a playground incident. The reporter interviews each student, asking challenging, real-life questions to help the students learn to effectively communicate while advancing a health-policy position. What starts as an intimidating experience ends up with students feeling confident and understanding how they can control a media situation to translate policy solutions, be culturally competent, and respond as an effective public health leader in difficult environments. The exercise, combined with classroom lectures, significantly strengthens these current or future professionals' communication skills, a critical public health competency.

The culminating experience

At the end of the course, students synthesize and integrate their new knowledge and skills, and apply them in a realistic advocacy situation. The exercise is designed to determine the students' abilities to communicate effectively with policy makers and the public, improve their teamwork skills, effectively define public health problems, and target public health policy strategies that can be implemented.

The last class is a mock U.S. congressional hearing on the proposed budget for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The intent of this active-learning model is to create a real-world environment where public health professionals focus on a specific public health problem, identify a potential policy solution, present related evidence-based information, and communicate with policy makers and the press.

Each student group coordinates two events: (1) a panel of governmental, nonprofit, and other interested parties testifying before the congressional committee, and (2) a press conference designed to generate media for the group's budget request. Each group determines its issue target. Each student must give an oral presentation of three minutes during one of the events, field questions, and submit a final paper representing his or her written testimony on any topic.

For mid-career professionals, an intensive three-day Health Advocacy course is periodically taught. All lectures and exercises remain the same, but the culminating event takes place in Washington, D.C., with actual congressional staff. In recent years, the chief of staff to the U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee and a health legislative aide to Senator Hillary Clinton have served as mock members of Congress, posing realistic questions in a realistic environment. This experience could be replicated around the country by forging teaching partnerships with practitioners engaged in local legislative activities.

Student course evaluation

The JHSPH Health Advocacy course is consistently one of the school's top-rated courses. In 2007, 84% of the participants rated it as excellent and 16% as good (none rated it as fair or poor). Based on the survey's open-ended responses, students value the practice-based training. Some examples of their responses are as follows:

This should be a required course. The skills taught are essential for any public health professional to be effective in what they do.

This was the most useful class I took at JHSPH. There aren't enough classes about getting all the research done here implemented—what's the purpose of having all the knowledge if you can't get people to listen to you?

The group exercises forced us to actually apply the techniques and knowledge. The writing assignments helped synthesize ideas and practice techniques.

CONCLUSION

In the maelstrom of rising disease rates, growing health disparities, and government budget battles, strong public health programs are needed now more than ever. But another decade will shortly pass and another IOM report will bemoan the disengagement of the public, press, and policy makers from public health and prevention solutions, unless we act now to strengthen the public health workforce's ability to translate science into policy action.

The advocacy gap needs to be addressed with courses specifically designed to teach policy implementation, action, and communication skills in our public health schools and programs. The JHSPH Health Advocacy course offers an innovative model for teaching multidisciplinary, real-world skills, along with an understanding of the policy-making process. In addition, schools must draw upon experienced practitioners in policy-making and advocacy to be a part of this educational training.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The future of public health. Washington: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebbie KM, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Institute of Medicine. Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. Who will keep the public healthy? [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Public Health Service (US), Public Health Functions Steering Committee and Working Group Subcommittee on Public Health Workforce, Training, and Education. Appendix E: competencies for providing essential public health services. [cited 2008 Feb 18];The public health workforce: an agenda for the 21st century. A report of the public health functions project, 1997. Available from: URL: http://www.health.gov/phfunctions/pubhlth.pdf.

- 5.Auld ME, Galer-Unti RA, Radius S, Miner KR. Making the grade in public health advocacy. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1984–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.1984-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorenson SB, Dorfman L, Wallack L. Social change for the public's health: developing a course outline for use in schools of public health. American Public Health Association 134th Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2006 Nov 4–8; Boston. [cited 2008 Mar 3]. Paper presented at. Available from: URL: http://apha.confex.com/apha/134am/techprogram/paper_131368.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownson RC, Kreuter MW, Arrington BA, True WR. Translating scientific discoveries into public health action: how can schools of public health move us forward? Public Health Rep. 2006;121:97–103. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delta Omega Honorary Society in Public Health. [cited 2007 Apr 3];Delta Omega award for innovative public health curriculum. Available from: URL: http://www.deltaomega.org/CurrAward.cfm.

- 9.Christoffel KK. Public health advocacy: process and product. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:722–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.5.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallack L, Dorfman L, Jernigan D, Themba M. Media advocacy and public health: power for prevention. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]