Abstract

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) controls signal transmission between cells in the nervous system. Abused drugs such as cocaine inhibit this receptor. Transient kinetic investigations indicate that inhibitors decrease the channel-opening equilibrium constant [Hess, G. P. & Grewer, C. (1998) Methods Enzymol. 291, 443–473]. Can compounds be found that compete with inhibitors for their binding site but do not change the channel-opening equilibrium? The systematic evolution of RNA ligands by exponential enrichment methodology and the AChR in Torpedo californica electroplax membranes were used to find RNAs that can displace inhibitors from the receptor. The selection of RNA ligands was carried out in two consecutive steps: (i) a gel-shift selection of high-affinity ligands bound to the AChR in the electroplax membrane, and (ii) subsequent use of nitrocellulose filters to which both the membrane-bound receptor and RNAs bind strongly, but from which the desired RNA can be displaced from the receptor by a high-affinity AChR inhibitor, phencyclidine. After nine selection rounds, two classes of RNA molecules that bind to the AChR with nanomolar affinities were isolated and sequenced. Both classes of RNA molecules are displaced by phencyclidine and cocaine from their binding site on the AChR. Class I molecules are potent inhibitors of AChR activity in BC3H1 muscle cells, as determined by using the whole-cell current-recording technique. Class II molecules, although competing with AChR inhibitors, do not affect receptor activity in this assay; such compounds or derivatives may be useful for alleviating the toxicity experienced by millions of addicts.

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) is a protein located in the plasma membrane of nerve and muscle cells. It belongs to a superfamily of membrane proteins that control signal transmission between approximately 1012 nerve cells in the mammalian nervous system. Upon binding acetylcholine, the receptor transiently (≈1 ms) forms a transmembrane channel. Inorganic cations move through the channel, thus changing the voltage across the cell membrane. This change in the transmembrane voltage initiates signal transmission in nerve cells and contraction in muscle cells. The receptor is inhibited by local anesthetics such as procaine and QX-222 and the anticonvulsant MK-801 [(+)-dizocilpine], as well as by tenocyclidine (TCP, thienyl cyclohexyl piperidine) and the abused drugs phencyclidine (PCP) and cocaine (1–6).

Cocaine abuse is widespread, with more than five million addicts in the United States alone (7). It can result in cardiac disease, sudden cardiac death, seizures, and neurologic disorders (8, 9). Cocaine inhibits the AChR (1, 10, 11) and also the dopamine and, possibly other, transporters (12, 13).

The mechanism of inhibition of the AChR by positively charged inhibitors, such as cocaine, has been based on the binding of radioactive inhibitors to the Torpedo AChR (14) and on electrophysiological measurements (15–17) of the effect of inhibitors on the lifetime of the open-receptor channel (18–20), determined by using the single-channel recording technique (21, 22). A simple mechanism based on these studies involves the binding of an inhibitor in the open-receptor channel and sterically blocking it (15, 18, 23–27). Recently, the existing techniques for investigations of receptor mechanisms have been supplemented by transient kinetic techniques suitable for measurements of receptor-mediated reactions on cell surfaces in the μs-to-ms time region (1, 5, 28–30). This technique allows one to determine the effects of inhibitors on the rate constants for both channel opening and closing and, therefore, on the channel-opening equilibrium constant, all in the same experiment (reviewed in ref. 31). The results obtained indicated that an important aspect of receptor inhibition involves the binding of inhibitors to the closed-channel form of the receptor, resulting in an inhibitor-induced decrease in the channel-opening equilibrium constant (refs. 1, 5, and 32, and reviewed in ref. 30). This suggested (1, 30) that compounds might be found that bind to the inhibitory site of the AChR without decreasing the channel-opening equilibrium constant; such compounds therefore may be useful for alleviating cocaine poisoning. Alternatively, compounds may be found that inhibit the AChR but still have desirable therapeutic values. MK-801 [(+)-dizocilpine] is an example. It has anticonvulsant properties, alleviates some effects of cocaine intoxication in rats (33, 34), and prevents N-methyl-d-aspartic acid-induced cell death (35). It also inhibits the AChR (36, 37).

One way to discover such compounds is to use an in vitro selection method known as the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) (38, 39). The SELEX method has been used for the isolation of RNA molecules from a large number (1013–1014) of different combinatorially synthesized RNAs that bind to a wide range of water-soluble target molecules with high affinity (38–42). Such targets have included proteins that naturally bind nucleic acids in vivo, including HIV type 1 (HIV-1) rev protein (43), and bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase (38). Water-soluble compounds that were not believed to naturally bind nucleic acids also have been used as targets for selection. These targets include basic fibroblast growth factor (44); substance P (45); several amino acids, such as arginine (46); antibodies (47); and cell adhesion molecules (48). The SELEX method can also be applied to the development of clinically useful therapeutic agents (44, 45, 49). For example, RNA aptamers have been selected for the ability to prevent growth factors from binding to receptors (44). Recently, the SELEX procedure was used to obtain ligands that bind to proteins in the membrane of red blood cells (50). Here we demonstrate that the technique can be used to obtain ligands that bind with high affinity to a specific site of a membrane-bound receptor.

We have established a SELEX protocol for the isolation of RNA aptamers that compete with cocaine for the cocaine-binding site of the AChR in the membrane of the electroplax of Torpedo californica. The electric organ is a very rich source of the AChR, and the membrane preparations contain about 0.7 nmol AChR-binding sites per mg membrane protein (14). The structures of this receptor and the AChR in the membrane of mammalian muscle cells are believed to be similar (51).

After nine selection rounds, RNA aptamers that bind with nanomolar affinities to the AChR in the electroplax membrane and that could be displaced from the receptor by PCP and cocaine were isolated and characterized. Analysis of the sequences of the 23 RNA aptamers obtained indicated that on a structural basis they fall into two distinct classes. A rapid mixing technique and whole-cell current recordings were used to determine the effects of the RNA molecules on the AChR activities in BC3H1 muscle cells. While one class of the RNA molecules are potent inhibitors of AChR activity, members of the other class do not affect receptor activity in this assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The sources of materials used are noted in the individual sections. All chemicals used were of the highest quality available. [125I]α-Bungarotoxin ([125I]α-BTX, 104–128 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) and [3H]TCP (46 Ci/mmol) were purchased from DuPont/NEN, and [32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham.

Preparation of Torpedo californica Electroplax Membrane and Determination of AChR Concentration.

The method of preparation was modified from the methods described by Szczwinska et al. (52). Frozen T. californica electric organs were purchased from Pacific Bio-Marine (Venice, CA). AChR-rich membrane vesicles were prepared by ultracentrifugation in a sucrose gradient. The receptor-rich membranes were recovered from the interphase between 36% (wt/wt) and 28% sucrose, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended at a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml.

The concentration of AChRs in the T. californica membranes was measured by [125I]α-BTX binding based on a method modified from Schmidt and Raftery (53). The range of specific activity of the membrane fraction was between 0.5 and 1.2 nmol α-BTX sites per mg of protein.

Binding of [3H]TCP to AChR-Rich Membranes.

Equilibrium binding of [3H]TCP to AChR-rich membranes (6) was measured by using a filtration assay. Briefly, 60 nM membrane-bound receptor was incubated with increasing concentrations of [3H]TCP in BC3H1 extracellular buffer (145 mM NaCl/5.3 mM KCl/1.8 mM CaCl2⋅2H2O/1.7 mM MgCl2⋅6H2O/25 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) (54), to give a final volume of 30 μl, for 40 min at 25°C. GF/F glass fiber filters (1.3 cm diameter) (Whatman) were presoaked in 1% Sigmacote in BC3H1 buffer (Sigma) (14) for 3 h, then aligned in a 96-well Minifold Filtration Apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell) and placed on top of one 11 × 14 cm GB002 gel blotting paper sheet (Schleicher & Schuell). Thirty-five microliters of each reaction mixture was spotted per well and washed twice with 200 μl ice-cold BC3H1 buffer. The filter-bound radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting. Samples containing between 10 nM and 1 μM [3H]TCP were diluted with unlabeled TCP to 10% of their original activity, and samples above 1 μM were diluted to 2% of their initial specific activity. [3H]TCP saturation curves were constructed by varying the [3H]TCP concentration from 50 nM to 10 μM. The amount of unspecific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM PCP. PCP, an analog of [3H]TCP, was also used as a competitor because it binds to the same inhibitory site of the receptor as cocaine (11) and TCP (14, 55).

SELEX for Isolation of Aptamers Displacing Cocaine from AChRs.

The RNA pool used in these selections was transcribed from a pool of DNA templates, each consisting of 108 nt with a 40-nt randomized region (N40) flanked by two constant regions containing together 68 nt (56). The sequence of the template was 5′-ACCGAGTCCAGAAGCTTGTAGTACT(N40)GCCTAGATGGCAGTTGAATTCTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAC-3′. The primers used to amplify the selected species following each selection round were 5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAATTCAACTGCCATCTA-3′ and 5′-ACCGAGTCCAGAAGCTTGTAGT-3′ (both synthesized by GIBCO).

Nitrocellulose filter-binding selection.

The transcribed RNA pool was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm (40 μg/1 ml RNA at 260 nm has an OD of 1.0) (57). The RNA pool was diluted to a final concentration of 50 μM in the reaction mixture in BC3H1 extracellular buffer at pH 7.4 (54). The pool was heated at 70°C for 10 min and left to cool to room temperature for 30 min to allow for proper secondary structure formation. The membrane-bound receptor fraction was added to give a final concentration of 500 nM AChR sites in the presence of 0.5 units/μl anti-RNase (Ambion), a DTT-independent ribonuclease inhibitor (58). BC3H1 buffer (54) was used to bring the total reaction volume to 400 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 40 min and then passed through nitrocellulose filters by using a 96-well Minifold filtration apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell). Both the AChR in the electroplax membrane and the RNA ligands bind strongly to this filter (59). Two hundred microliters of reaction mixture was spotted per well onto an 11 × 14 cm BA85 0.45-μm nitrocellulose sheet over a sheet of 11 × 14 cm GB002 gel blotting paper (Schleicher & Schuell). Each spot was washed four times with 200 μl ice-cold BC3H1 buffer. The spots were excised from the nitrocellulose sheet. The excised nitrocellulose pieces containing the receptor-bound RNA were incubated for 20 min in 100 μl of a 1-mM PCP solution. The pieces were then clamped to the top of 1.5-ml microfuge tubes, and the eluate was collected in the bottom of the microfuge tubes by centrifugation (400 × g, 3 min). This eluate was added to the PCP solution in which the nitrocellulose pieces had been incubated and then extracted with 100 μl phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol (25:24:1). The supernatant was extracted with 100 μl chloroform. The organic layer was reextracted with 100 μl TE buffer (10 mM Tris/1 mM EDTA, pH 7.6). The supernatants were pooled and ethanol-precipitated (80%) in a total volume of 1 ml in the presence of 10 μg yeast tRNA (GIBCO) (57). The DNA pool needed for the next selection round was restored by reverse transcription–PCR (60). The DNA pool was in vitro-transcribed as described for the next round.

Gel-shift selection.

In selection rounds 1–3 only the filter-binding selection was used. In selection rounds 4–9, the gel-shift-selection method (61) was used before the filter selection technique to isolate cocaine-site-specific aptamers. The RNA pool was diluted to a final concentration of 30 μM in the reaction mixture in BC3H1 extracellular buffer and heated at 70°C for 10 min. The RNA was left to cool to room temperature for 30 min to allow for proper secondary structure formation. The RNA then was incubated with membranes containing 100 nM AChR in the presence of 0.3 unit/μl anti-RNase in a final volume of 80 μl for 40 min at room temperature. After incubation, 5% glycerol and 0.04% bromophenol blue (BDH) were added to the mixture (57). The mixture was loaded onto a 3% native acrylamide gel in TBE (89 mM Tris/89 mM boric acid/2 mM EDTA) adjusted to pH 7.4 (57). The gel was cast in a vertical electrophoresis system (GIBCO) of dimensions 15 × 17 × 0.3 cm. The gel was run at 7 V/cm (54) for 3 h at room temperature. The gel was removed and stained in SYBR Green II RNA stain (FMC) (62) for 10 min, and the band containing the RNA–protein complex was excised and eluted in 200 ml elution buffer [0.5 M ammonium acetate, pH 5.2/1 mM DTT/0.2 unit/ml DTT-dependent ribonuclease inhibitor (GIBCO)] on a vertical rotator (40 rpm) for 12 h at 37°C. The polyacrylamide was pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was passed through a 0.2-μm Whatman nylon 66 syringe filter. The supernatant (200 μl) was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol (25:24:1) and then with chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol as described above.

Aptamer amplification/preparation.

After each round of selection, the ethanol-precipitated RNA (approximately 0.1 μg) was reverse-transcribed and amplified by using the primers listed above and the Titan One-Tube RT-PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim) or the Superscript Kit (GIBCO) and purified by nondenaturing PAGE (61). These DNAs (10 μg DNA) were transcribed for the next round of selection by using the Maxiscript Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Before being used in the BC3H1 cell assay (1, 54), the individual aptamers were cloned and transcribed as described above. Before a cell assay measurement, the aptamer solution was diluted to the appropriate concentration in BC3H1 buffer (54) and then heated at 70°C for 10 min and left to cool to room temperature for 30 min to allow for proper secondary structure formation.

Binding Analyses.

Gel-shift analysis. A 3% acrylamide gel was prepared as described in the gel-selection protocol. 32P-labeled RNA was prepared as above. RNA (2 × 106 cpm) was diluted with BC3H1 buffer, heated and cooled as above, and added to a reaction tube containing 100 nM receptor/5 μg/μl tRNA (GIBCO)/0.3 unit/μl anti-RNase. A sample also was prepared without receptor to measure the background radiation of the gel. The samples were incubated for 40 min at room temperature, loaded onto the gel, and run at room temperature as described above. The gel was removed after 3 h and imaged by using a phosphorimaging plate (Fuji). The imaging plate was scanned by using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager, and band intensities were quantified by using the imagequant software from Molecular Dynamics.

IC50 determinations.

The IC50 value is the concentration at which an inhibitor displaces 50% of a radioactive ligand from a protein. One microgram of DNA template in 25 μl of transcription buffer was transcribed in the presence of 50 μCi [32P]UTP using the Maxiscript Kit (Ambion) and purified by using a Spin Column 30 (Sigma) (63). [32P]UTP-labeled RNA (5 × 105 cpm) in the presence of 20 nM unlabeled RNA was incubated with 100 nM receptor in the presence of 0.1 μg/μl tRNA (GIBCO) and 0.1 unit/μl anti-RNase (Ambion) in 35 μl BC3H1 buffer (54) in the presence of increasing concentrations of cocaine from 0 to 10 mM for 40 min at room temperature. The reaction mixtures were separated on Whatman 1.3-cm GF/F filters that were aligned in the Minifold Filtration Apparatus and placed on top of one 11 × 14 cm GB002 gel-blotting paper sheet (Schleicher & Schuell). The filters were washed twice with 200 μl ice-cold BC3H1 buffer. The filters were removed and scintillation was counted.

Individual Aptamer Characterization.

After SELEX cycle 9, the cDNA pool of the RNA aptamers was cut with EcoRI and HindIII (GIBCO) at the constant regions and ligated into the vector pGEM-3Z (Promega) (64). The recombinant vectors were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain JM109 and plated (57). Colonies were picked and inserts were sequenced (65) at the Cornell DNA-sequencing facility. RNA structures were predicted by using the mfold program (66) server at http://www.ibc.wustl.edu/∼zuker/rna/form1.cgi.

Cell Culture and Whole-Cell Current Recording.

The BC3H1 cell line expressing the muscle-type AChR (67) was cultured as described elsewhere (68). The equilibration of BC3H1 cells with carbamoylcholine, a stable acetylcholine analog, cocaine, and aptamers, using a cell-flow technique, and the determination of the resulting whole-cell current (69) due to the opening of receptor channels have been described in detail (1, 54). BC3H1 extracellular buffer (54) was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SELEX Procedure.

Unlike the AChR in the native electroplax membrane, the purified receptor extracted from the membrane binds inhibitors such as cocaine poorly (M. E. Eldefrawi, personal communication). However, using the receptor in the native membrane poses a number of problems, including the binding of RNA molecules to other components in the membrane (50) and the retention of RNA by solutions contained within the membrane fragments. Therefore, after the initial three selection cycles using only nitrocellulose filters, two consecutive selection processes were used (Fig. 1). The first was a gel-shift selection of high-affinity ligands bound to the AChR in the electroplax membrane. Then, after elution and amplification of the receptor-bound RNA, the nitrocellulose filter-selection procedure was used. Both the AChR in the electroplax membrane and the RNAs bind strongly to these filters. We reasoned that the RNA bound to the inhibitory site of the AChR could be displaced by the high-affinity inhibitor PCP. Using a tritium-labeled PCP analog, [3H]TCP, to elute the desired RNA aptamers, we found that only 45 nM PCP but 15 μM cocaine was required to displace 50% of the [3H]TCP bound to the AChR in the electroplax membrane (results not shown). PCP was, therefore, used as a selection agent in the SELEX method.

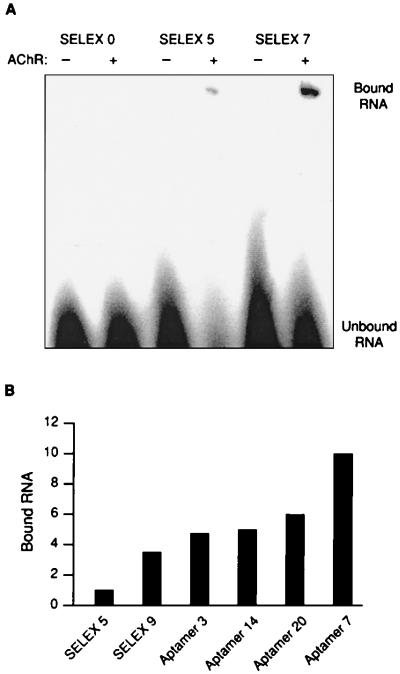

Figure 1.

Gel-shift binding assay. Gel-shift assays were performed to analyze the binding affinity of the RNA SELEX pools and of individually cloned aptamers to the AChR membrane fraction. In these reactions, 2.5 μg/μl tRNA was used to decrease nonspecific binding of 500 pM [32P]RNA to 0.2 μg/μl membrane fraction containing 60 nM AChR-binding sites. Each RNA-binding reaction was carried out in the presence and absence of membrane AChR to analyze the [32P]RNA background on the gel. After a 40-min incubation, glycerol and bromophenol blue were added to a final concentration of 5% and 0.03%, respectively, in the reaction tubes and the samples were loaded onto a 3% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (57). The gel was run at 10 V/cm for 3 h. The gel was analyzed by phosphorimaging (71), and the protein-bound radioactivity was quantified using imagequant software (Molecular Dynamics). (A) Comparison of the original SELEX pool with SELEX pool 5 and SELEX pool 7. The intensity of the SELEX 7 aptamer-AChR band corrected for background is 4-fold greater than the SELEX 5 pool. The intensity of the SELEX 0 pool is less than the background signal, so no comparison can be made. (B) Enrichment of RNA binding to electroplax membranes containing AChR. RNA pools obtained from different selection rounds and single-cloned RNA molecules denoted class I aptamers 7, 14, and 20 and class II aptamer 3 were analyzed using the gel-shift binding assay as described above. The intensities of RNA bound to the membrane fractions obtained by phosphorimaging are compared with the amount of membrane-bound RNA of the fourth selection pool, the intensity of which was set to 1.0.

Isolation of Cocaine-Displaceable RNA Aptamers.

The gel-shift assay was used to follow the selection of RNA aptamers. Even after three nitrocellulose-filter-selection procedures RNA binding to the membrane-bound AChR at the origin of the gel could not be detected (Fig. 1A). However, after selection rounds 4 and 5 in which both the gel-shift and the filter-binding procedures were used, radiolabeled RNA binding to the receptor could be detected in the gel-shift assay (Fig. 1A). The concentration of receptor-bound RNA increased until the seventh selection (Fig. 1A), but did not increase thereafter. The relative amounts of receptor-bound RNA, both after selection cycle 9 and in the cases of the individual cloned class I aptamers 7, 14, and 20 and class II aptamer 3, are shown in Fig. 1B. (The distinction between aptamers of classes I and II are discussed in the next section.)

Primary and Secondary Structure of Class I and Class II Aptamers.

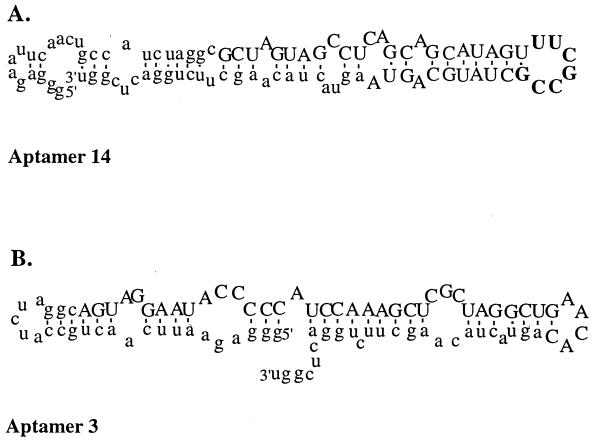

Aptamers from SELEX pool 9 were cloned, isolated, and sequenced (see Materials and Methods). Two classes of aptamers were obtained. The 7-nt consensus sequence of 14 of the class I aptamers is shown in Table 1. Interestingly, the mfold structure prediction program (66) integrated this consensus sequence within a stem–loop structure (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2A shows the prediction of the secondary structure of the consensus sequence of class I aptamer 14 within a stem loop. Class II aptamers do not have the consensus sequence displayed by class I aptamers. The secondary structure of the class II aptamer 3, predicted by the mfold program (66), is shown in Fig. 2B.

Table 1.

Primary structures of high affinity cocaine-displaceable class I RNA aptamers

| Aptamer | Structure |

|---|---|

| 01 | ACGUUGAGUACAACCCCACCCCGUUCACGGUAGCCCUGUA |

| 05 | GCUACAGUACAACGGGCCGUGUGGAAUACACCGACAAGG |

| 06 | UCCACCGAUCUAGAUGAUCCAGGCACCCGACCACCACCUC |

| 07 | GCUUGUGGACCAAGAAGCAACCAGUCACCGUUGCCCC |

| 09 | CAACAGUCCUGUGUCCGUUGAAUCCUCUAGAUCCAGGGUG |

| 11 | GGACCCCCCACAGCAAGUUUGCCGGCGACCGCGUUCUUG |

| 13 | CUUGCCACUCCUGUCUAGCUGGCGUAGACCGCGCAGAAAG |

| 14 | GCUAGUAGCCUCAGCAGCAUAGUUUCGCCGCUAUGCAGUA |

| 16 | UAGCAUAAUGUGGAGCGUUGACCGGACCUCUCCAGUCGUA |

| 18 | UGGACUACGCACCCGCUAGUCCGUCCAAGAACUGUGCG |

| 19 | UUCUGUUCCGACCAAUUGAAUAGUCACCGUGAUGAUUUGA |

| 20, 21 | GAUGCCAGCGCGCAUUCUUCACCGAAGUACGUAUCCACG |

| 22 | UUCGCCGCUGCACUCUCGCAGCACUGGUCGGGAUGUGUC |

| Consensus | UUCACCG | ||||||

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Consensus | U | U | C | A | C | C | G |

| Frequency | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 13 | 14 |

After nine rounds of selection, the RNA pool was reverse-transcribed, ligated into pGEM-3Z (Promega), and transformed into E. coli strain JM109. Twenty-three clones were identified and sequenced. A 7-nt consensus region was found in 14 clones consisting of UUCACCG. Listed are the positions, nucleotides, and frequencies of the consensus region.

Figure 2.

Secondary structures of aptamers 3 and 14. The sequences of the aptamers were entered into the mfold program (66) to determine the RNA secondary structure at 25°C. (A) The predicted secondary structures of RNA aptamer 14, which is representative for class I. The variable region is in uppercase letters, and the shared sequence motif is in boldface. (B) The secondary structure of class II aptamer 3 that does not contain the consensus sequence found in class I aptamers. The variable region is in uppercase letters.

Affinity of Class I and Class II Aptamers for the Membrane-Bound AChR.

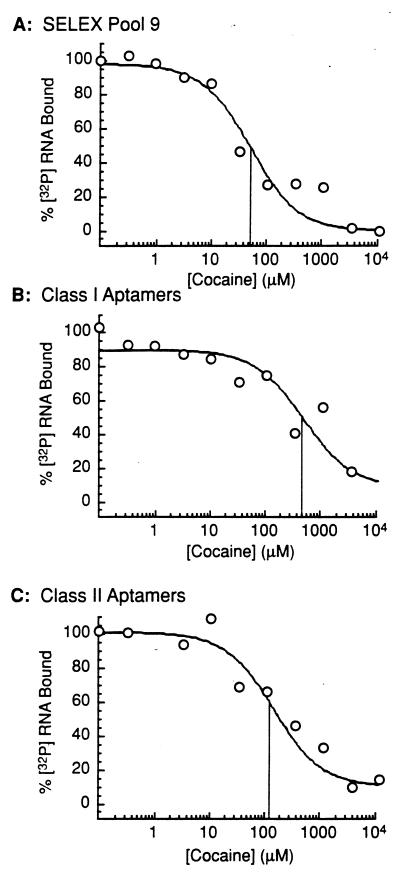

The ability of cocaine to displace aptamers of classes I and II from the AChR in the electroplax membrane was determined by using GF/F glass-fiber filters (Fig. 3). Comparing the concentration of cocaine at which 50% of the aptamers were displaced from the AChR in the electroplax membrane, it was found that some class I aptamers (Fig. 3B) bind with an approximately 10-fold-higher affinity and a class II aptamer binds with approximately a 4-fold-higher affinity (Fig. 3C) than the pool of aptamers after nine selections (Fig. 3A). With the assumption that cocaine binds with an apparent Kd (app) of 50 μM to the membrane-bound AChR (1), it can be calculated (70) from the data shown in Fig. 3 that class I aptamers bind to the membrane-bound AChR with an apparent Kd (app) of 2 nM and class II aptamers bind with a Kd (app) value of 12 nM.

Figure 3.

Displacement of [32P]RNA using cocaine as a competitor. The experiments were performed by using a constant 20-nM concentration of RNA ([32P]RNA aptamer and unlabeled aptamer) in the presence of 0.3 μg/μl tRNA to reduce nonspecific binding and 100 nM receptor in the membrane fraction. The reaction mixtures were separated by filtration using 1.3-cm GF/F glass fiber filters that had been soaked in 1% Sigmacote (Sigma) (14) in BC3H1 buffer, pH 7.4. The radioactivity retained on the filters was estimated by scintillation counting. The concentration of cocaine required to displace 50% of the RNA aptamer from the binding site, the IC50 value, was calculated by fitting the data to the equation Y = Bmin + (Bmax − Bmin)/(1 + [cocaine]/IC50) (72). Y is the total binding in the presence of various concentrations of cocaine, Bmin is the minimum amount of [32P]RNA bound, and Bmax is the maximum amount of [32P]RNA bound. (A) RNA SELEX pool 9 (IC50: 50 μM). (B) RNA pool of three cloned class I aptamers denoted 7, 14, and 20 (IC50: 500 μM). (C) Class II aptamer 3 (IC50: 110 μM).

Do the Aptamers Affect the Function of the Muscle AChR?

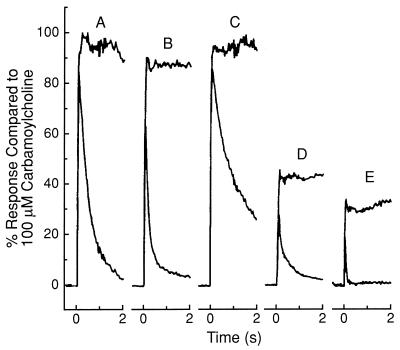

A combination of the whole-cell current-recording (69) and cell-flow (54) techniques was used to determine the effects of the aptamers on the function of the AChR in BC3H1 muscle cells. In Fig. 4 the maximum current amplitude obtained with 100 μM carbamoylcholine was taken as 100% activity. It can be seen that at a concentration of 5 μM neither the original pool of RNA aptamers nor aptamer 3, a member of class II (Fig. 2B), affect the activity of the receptor (Fig. 4 B and C). Similar results were obtained with all 10 aptamers in class II used at a concentration of 10 μM. In contrast, class I aptamers that have a consensus sequence not found in class II compounds are potent inhibitors when used at a concentration of 1 μM. Measurements have been made with 12 of these aptamers. A typical experiment is shown with aptamer 14 (Figs. 2A and 4E). At a concentration of 0.5 μM this compound is a more potent receptor inhibitor than 100 μM cocaine (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of the BC3H1 AChR by single-cloned RNA aptamers. A combination (54) of the cell-flow (54) and whole-cell current-recording (69) techniques was used at a membrane potential of −60 mV at 22°C in BC3H1 buffer, pH 7.4. The whole-cell currents were generated by 100 μM carbamoylcholine after 2-sec preincubation with 0.1 μg/μl tRNA and 0.3 unit/μl anti-RNase alone (A), plus 5 μM SELEX pool 0 (B), plus 5 μM class II aptamer 3 (C), plus 100 μM cocaine (D), and plus 0.5 μM class I aptamer 14 (E). The lines parallel to the abscissa represent currents corrected for receptor desensitization (54).

The experiments presented describe an efficient approach for using the SELEX technique to obtain high-affinity ligands for a regulatory site of a membrane-bound protein, the AChR. Two classes of high-affinity ligands that compete with cocaine for a receptor site (Fig. 3 B and C) were identified using this approach. The consensus sequence found in one class (class I) of these ligands (Table 1) is not found in the second class. Class I consists of efficient inhibitors of receptor function, while class II does not (Fig. 4). The existence of these two types of compounds was suggested by transient kinetic investigations, which indicated that compounds inhibit the receptor by causing a decrease in the channel-opening equilibrium constant (1, 30).

The successful use of the SELEX method with membrane-bound proteins demonstrated in this study is promising for finding ligands that may alleviate the toxic effect of some compounds such as cocaine on membrane-bound receptors and, therefore, on the organism. The results reported indicate that the chemical kinetic approach, which predicted the existence of compounds that can bind to an inhibitory site without changing the channel-opening equilibrium constant, may be useful in answering many of the remaining questions regarding the chemical mechanism by which neurotransmitter receptors are affected by a large number of clinically useful compounds (3) and by abused drugs like cocaine. The approach may also be useful in finding compounds that inhibit receptor function but still have therapeutic value, such as MK-801 (33–37). Determining the length of the RNA aptamers required for their effect on the AChR and stabilizing the aptamers for clinical trials appear to be interesting problems for the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (NS08527) awarded to G.P.H. by the National Institutes for Neurological Diseases and Stroke, a grant (GM52277) awarded to V.A.E. by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, a postdoctoral fellowship awarded to H.U. by the American Heart Association, New York State Affiliate, and a Viets Graduate Fellowship awarded to O.R.P. by the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. We are grateful to Professor Leo G. Abood, Department of Pharmacology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY (deceased 1998), for guidance and help on the pharmacology of receptors and for his friendship. This article is dedicated to his memory. We are grateful to Professor Jack W. Szostak, Harvard University Medical School, for helpful comments on the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- SELEX

systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment

- PCP

phencyclidine

- TCP

tenocyclidine (thienyl cyclohexyl piperidine)

References

- 1.Niu L, Abood L G, Hess G P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12008–12012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramoa A S, Alkondon M, Aracava Y, Irons J, Lunt G G, Deshpande S S, Wonnacott S, Aronstam R S, Albuquerque E X. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:71–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilman A G, Rall T W, Nies A S, Taylor P, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: Pergamon; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguayo L G, Albuquerque E X. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;239:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niu L, Hess G P. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3831–3835. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz E J, Cortes V I, Eldefrawi M E, Eldefrawi A T. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;146:227–236. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redda K K, Walker C A. Cocaine, Marijuana: Chemistry, Pharmacology and Behavior. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1993. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lathers C M, Tyau L S Y, Spino M M, Agarwal I. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;28:584–893. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karch B S. The Pathology of Drug Abuse. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidmann T, Changeux J-P. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47:317–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karpen J W, Hess G P. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1777–1785. doi: 10.1021/bi00355a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhar M J, Ritz M C, Boja J W. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:299–302. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90141-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giros B, Jaber M, Jones S R, Wightman R M, Caron M G. Nature (London) 1996;379:606–612. doi: 10.1038/379606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eldefrawi M E, Eldefrawi A T, Aronstam R S, Maleque M A, Warnick J E, Albuquerque E X. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7458–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams P R. J Physiol (London) 1976;260:531–532. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams P R. J Physiol (London) 1977;268:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gage P W, Wachtel R E. J Physiol (London) 1984;346:331–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neher E, Steinbach J. J Physiol (London) 1978;277:153–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neher E. J Physiol (London) 1983;339:663–678. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papke R L, Oswald R E. J Gen Physiol. 1989;93:785–811. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neher E, Sakmann B. Nature (London) 1976;260:861–863. doi: 10.1038/260799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakmann B, Neher E. Single-Channel Recording. 2nd Ed. New York: Plenum; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odgen D C, Colquhoun D C. Proc R Soc London B. 1985;225:329–355. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1985.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlin A. Harvey Lect. 1991;85:71–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galzi J-L, Revah F, Bessis A, Changeux J-P. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1991;31:37–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.31.040191.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lester H A. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:267–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lena C, Changeux J P. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90150-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milburn T, Matsubara N, Billington A P, Udgaonkar J B, Walker J W, Carpenter B K, Webb W W, Marque J, Denk W, McCray J A, Hess G P. Biochemistry. 1989;29:49–55. doi: 10.1021/bi00427a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsubara N, Billington A P, Hess G P. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5507–5514. doi: 10.1021/bi00139a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess G P, Grewer C. Methods Enzymol. 1998;291:443–473. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)91028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess G P, Niu L, Wieboldt R. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;757:23–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb17462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu L, Grewer C, Hess G P. Techniques Protein Chem. 1996;VII:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rockhold R W, Surrett R S, Acuff C G, Zhang T, Hoskins B, Ho I K. Neuropharmacol. 1992;31:1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90056-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karler R, Calder L D, Chaudhry I A, Turkanis S A. Life Sci. 1989;45:599–606. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olney S W, Price M T, Salles K S, Labruyhre J, Friedrich G. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;141:357–361. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramoa A S, Alkondon M, Aracava Y, Irons J, Lunt G G, Deshpande S S, Wonacott S, Aronstam R S, Albuquerque E X. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:71–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amador M, Dani J A. Synapse. 1991;7:207–215. doi: 10.1002/syn.890070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuerk C, Gold L. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellington A D, Szostak J W. Nature (London) 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gold L, Polisky B, Uhlenbeck O, Yarus M. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:763–797. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Famulok M, Szostak J W. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3990–3991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sassanfar M, Szostak J W. Nature (London) 1993;364:550–553. doi: 10.1038/364550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu W, Ellington A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7475–7480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jellinek D, Lynott C K, Rifkin D B, Janjic N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11227–11231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nieuwlandt D, Wecker M, Gold L. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5651–5659. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connell G J, Illangesekare M, Yarus M. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5497–5502. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamm J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2220–2227. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Connell D, Koenig A, Jennings S, Hicke B, Han H-L, Fritzwater T, Chang Y-F, Varki N, Parma D, Varki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5883–5887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gold L. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13581–13584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris K N, Jensen K B, Julin C M, Weil M, Gold L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2902–2907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hucho F, Tsetlin V I, Machold J. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:539–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0539u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szczwinska K, Ferchmin P A, Hann R M, Eterovic V A. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1992;12:95–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00713364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt J, Raftery M A. Anal Biochem. 1973;52:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Udgaonkar J B, Hess G P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8758–8762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hann R M, Pagan O R, Gregory L, Jacome T, Rodriguez A D, Ferchmin P A, Lu R, Eterovic V A. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi H, Hoffman B E, Lis J T. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2649–2657. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy N R, Leinbach S S, Hellwig S S. BioTechniques. 1995;18:1068–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yarus M. Anal Biochem. 1976;70:346–353. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liang P, Pardee A B. Science. 1992;257:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blackwell T K. Methods Enzymol. 1995;254:604–618. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)54043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin X, Yue S, Wells K S, Singer V L. FASEB J. 1994;8:A1266. (abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hagel L, Lundstrom H, Andersson T, Lindblom H. J Chromatogr. 1989;476:329–344. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)93880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yanish-Perron C, Viera J, Messing J. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosenblum B B, Lee L G, Spurgeon S L, Khan S H, Menchen S M, Heiner C R, Chen S M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4500–4504. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zuker M, Jacobson A B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2791–2798. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schubert D, Harris A J, Devine C E, Heinemann S. J Cell Biol. 1974;61:398–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.61.2.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sine S M, Taylor P. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:3315–3325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamill O P, Marty A, Neher B, Sakmann B, Sigworth F J. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng Y-C, Prusoff W H. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnston R F, Pickett S C, Barker D L. Electrophoresis. 1990;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150110503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McPherson G A. J Pharmacol Methods. 1985;14:213–228. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]