Abstract

AIMS

Using an established model of smokers cough we measured the antitussive effects of dextromethorphan compared with placebo.

METHODS

The study was a randomized, double-blind placebo controlled, crossover comparison of 22 mg 0.8 ml−1 dextromethorphan delivered pregastrically with matched placebo. Objective and subjective measurements of cough were recorded. Subjective measures included a daily diary record of cough symptoms and the Leicester quality of life questionnaire. Cough frequency was recorded using a manual cough counter. The objective measure of cough reflex sensitivity was the citric acid, dose–response cough challenge.

RESULTS

Dextromethorphan was significantly associated with an increase in the concentration of citric acid eliciting an average of two coughs/inhalation (C2) when compared with placebo, 1 h post dose by 0.49 mM (95% CI 0.05, 0.45, geometric mean 3.09) compared with placebo 0.24 mM (geometric mean 1.74) P < 0.05 and at 2 h 0.57 mM (95% CI 0.01, 0.43, geometric mean 3.75) compared with placebo 0.34 mM (geometric mean 2.19) P < 0.05). There was a highly significant improvement in the subjective data when compared with baseline. However, there was no significant difference between placebo and active treatment. No correlation was seen between cough sensitivity to citric acid and recorded cough counts or symptoms. When both subjective and objective data were compared with screening data there was evidence of a marked ‘placebo’ effect.

CONCLUSIONS

The objective measure of cough sensitivity demonstrates dextromethorphan effectively diminishes the cough reflex sensitivity. However, subjective measures do not support this. Other studies support these findings, which may represent a profound sensitivity of the cough reflex to higher influences.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Dextromethorphan is widely used as a cough suppressant in over the counter medications.

Its efficacy in altering cough reflex sensitivity has been shown in healthy volunteers. In contrast evidence for an effect on clinically important cough is poor.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

A significant decrease in evoked cough was seen with dextromethorphan compared with placebo. However, both placebo and active treatment improved subjective data to a similar degree.

We doubt the validity of currently used objective tests in the investigation of antitussives.

Keywords: antitussive, cough, dextromethorphan, smoking

Introduction

The alteration of the cough reflex sensitivity by dextromethorphan has previously been demonstrated in healthy subjects [1, 2] using citric acid challenge. However, when tested on clinical parameters results are less impressive. In one study of patients with chronic cough, dextromethorphan was found to be as effective at reducing cough frequency and intensity as was codeine [3]. However, this study was not placebo controlled and in the evaluation of antitussive efficacy the placebo response may be highly significant. A review of eight clinical trials examining the effects of antitussive medicines on cough associated with acute upper respiratory tract infection showed that 85% of the reduction in cough was related to treatment with placebo [4]. In a placebo controlled trial of dextromethorphan vs. glaucine in chronic cough, only glaucine was found to be significantly different from placebo, at reducing objective measures of cough [5]. In a study of children with upper respiratory tract infection, subjective measures were made and neither dextromethorphan nor codeine were significantly more effective than placebo [6]. A meta analysis of three placebo controlled studies of dextromethorphan in acute cough was required to demonstrate a modest reduction of cough [7]. Despite the fact that dextromethorphan is one of the most commonly used antitussives for the treatment of cough associated with upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), there is surprisingly little evidence to support efficacy in this disease state or indeed in others characterized by chronic cough. Investigating the efficacy of antitussives in acute settings is problematic. In natural URTI the cough is acute with a varying degree of severity and time course and is caused by a variety of viruses. Moreover, because of the variability of this condition it is likely that most previous studies have not been adequately powered to demonstrate a significant effect of dextromethorphan. The nature of chronic cough is less variable [8], and smaller groups can be used when investigating chronic cough.

We have therefore performed a study to test the efficacy of dextromethorphan in a clinical cough using a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover design, assessing both subjective and objective measures. To do this, we have used our previously described model of smoking related cough [9], which we suggest is associated with airway inflammation.

Methods

We used an established model of smokers cough [9] to measure the antitussive effects of dextromethorphan compared with placebo in 42 healthy, currently smoking volunteers.

The study was a randomized two-way cross-over to determine the efficacy of optimized oral cough formulation (22 mg 0.8 ml−1) dextromethorphan base, equivalent to 30 mg dextromethorphan hydrobromide delivered pregastrically (designed to deliver 3–5 fold greater bioavailability by largely bypassing first-pass metabolism [10]) vs. placebo on smokers cough. The taste of both active and placebo medication were masked by a grape flavoured excipient.

Primary efficacy endpoint was a reduction in cough frequency measured subjectively after waking on treatment day 1 over epocs 0–10, 10–20, 20–40, and 40–60 min prior to smoking. Secondary end point was reduction in cough frequency on days 2–5, change in cough symptoms (severity, expectoration, chest pain, etc., as measured on a visual analogue score) and nocturnal cough. Change in cough threshold as measured via citric acid cough challenge was a further secondary end point.

Healthy male and female smokers with troublesome cough were randomized. Patients had to be currently smoking 15 cigarettes day−1 and have at least a 10 pack year smoking history. Morning cough was required on all 5 days of the screening diary and volunteers had to have a 3 month history of morning cough. Volunteers underwent initial screening which assessed salbutamol reversibility (<12% increase in baseline FEV1 with 400 µg salbutamol via MDI and spacer) and a methacholine challenge (provocative dose causing a 20% fall in FEV1 (PD20) < 0.5 mg). These tests were performed in order to exclude any volunteers with evidence of either asthma or COPD. Following successful completion of screening, patients recorded cough symptoms in a daily screening diary for 5 days and then returned for the first of two treatment visits, during which they continued to record cough symptoms. Volunteers were admitted on the night prior to treatment visit 1, filled out the Leicester Cough Questionnaire [10] and were allowed to smoke at will, until midnight. The next morning following abstinence from smoking, coughing bouts were measured with cough counters for 0–20 min upon waking. Following this, subjects performed a baseline citric acid cough challenge and then received either 0.8 ml dextromethorphan or matched placebo. Cough frequency was manually recorded over 10 min periods for the following 240 min. A further three cough challenges were performed at 1, 2 and 4 h post dose. At 1 h post dose subjects were allowed to smoke freely until the end of the study visit. At the end of the study visit a further dose of either placebo or dextromethorphan was administered to subjects. Patients went home with a diary card and their allotted treatment. The subjects recorded cough frequency and cough symptoms for 5 days whilst taking their allotted treatment three times a day (morning, midday and evening). Subjects returned to the clinical trials unit 7–14 days post final treatment with their allotted medication. All procedures of treatment visit 1 were mirrored in treatment visit 2.

The citric acid cough challenge was performed using our previously described methodology [11]. Briefly inhalation of incremental concentrations of citric acid (1 mM, 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 100 mM, 300 mM, 1000 mM) interspersed with two inhalations of normal saline to increase challenge blindness. Patients were instructed to exhale to functional residual capacity and then inhale through the mouthpiece. The number of coughs in the first 10 s after each inhalation was then recorded.

Results are expressed as arithmetic mean with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for cough frequency and geometric mean for citric acid cough challenge (C2). Statistical comparison was by paired t-test. Hypotheses tests were two-sided and of 5% significance level. The results were analyzed on an intention to treat basis. Analysis of variance for daytime and night-time diary cough related symptoms was made using the anova and Tukey post hoc test.

Sample size

Sample size and power for crossover trials has been discussed extensively in the literature [12–15]. Consensus is that they require fewer patients than the parallel group design. We found no significant difference between placebo and active treatment on subjective data, and this could be due to lack of statistical power. Using software developed by D.A. Schoenfeld (http://www.hedwig.mgh.harvard.edu/sample_size) setting power at 80%, significance at 5% (two-tailed), then a standardized difference of 0.4 (with an allowance for rounding errors) can be detected with 48 patients (taking into account the crossover design). A standardized difference of 0.4 represents a ‘medium’ effect size and we would argue that this is a clinically important difference. Halving this difference quadruples the numbers.

Results

Seventy-two patients were screened and all gave informed consent. Of these 24 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria. Forty-eight patients were randomized and 42 completed the study with six drop outs due to patients withdrawing consent. Twenty-two females and 20 males of age range 23–61 years (mean 38.5) were recruited. Patients' smoking history, FEV1, salbutamol reversibility, and PD10 are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42 | 23 | 61 | 38.5 |

| Pack years | 42 | 10 | 80 | 26 |

| FEV1 (l) | 42 | 1.93 | 5.03 | 3.6 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 42 | 80.4 | 155.5 | 105.5 |

| FVC (l) | 42 | 2.55 | 6.9 | 4.6 |

| FVC (% predicted) | 42 | 90.2 | 152 | 113 |

| PEF (l min−1) | 42 | 260 | 669 | 497.6 |

| PEF (% predicted) | 42 | 76 | 139 | 105.4 |

| FEV1 : FVC | 42 | 65.8 | 97.3 | 79.4 |

| Reversibility (%) | 42 | −2.9 | 8.4 | 3.0 |

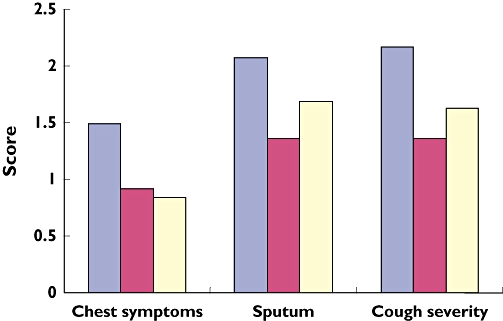

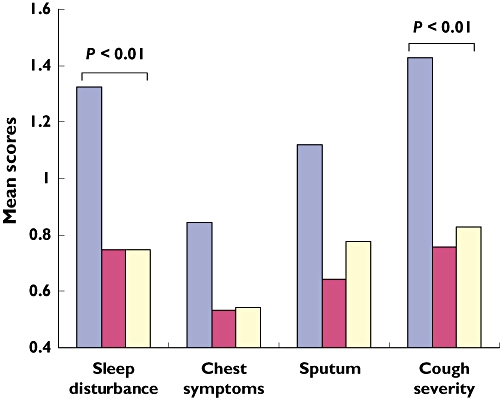

Using the anova and Tukey post hoc test there was no significant difference in daytime or night-time daily cough symptoms between placebo and dextromethorphan (Figures 1 and 2). However, there were significant (P < 0.05) differences between diary symptoms at screening and post intervention (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Daytime diary, cough related symptoms (screening, ( ); Dextromethorphan, (

); Dextromethorphan, ( ); placebo, (

); placebo, ( ))

))

Figure 2.

Night-time diary, cough related symptoms (screening, ( ); Dextromethorphan, (

); Dextromethorphan, ( ); placebo, (

); placebo, ( ))

))

Table 2.

Diary data

| 95% confidence interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | Lower | Upper | ||

| Sleep disturbance | ||||

| Screening | Dex | 0.006 | 0.140 | 1.014 |

| Placebo | 0.006 | 0.139 | 1.013 | |

| Dex | Placebo | 1.000 | −4.387 | 4.363 |

| Night-time severity | ||||

| Screening | Dex | 0.003 | 1.866 | 1.156 |

| Placebo | 0.010 | 0.115 | 1.084 | |

| Dex | Placebo | 0.936 | −0.557 | 0.413 |

| Daytime severity | ||||

| Screening | Dex | 0.027 | 0.007 | 1.520 |

| Placebo | 0.195 | −0.190 | 1.257 | |

| Dex | Placebo | 0.670 | −0.987 | 0.461 |

| Daytime QOL | ||||

| Screening | Dex | 0.014 | 0.108 | 1.199 |

| Placebo | 0.007 | 0.154 | 1.245 | |

| Dex | Placebo | 0.978 | −0.500 | 0.592 |

| Daytime chest symptoms | ||||

| Screening | Dex | 0.020 | 0.007 | 1.070 |

| Placebo | 0.007 | 0.149 | 1.146 | |

| Dex | Placebo | 0.932 | −0.422 | 0.574 |

anova and Tukey post hoc test, P values and 95% confidence intervals. DEX dextromethorphan.

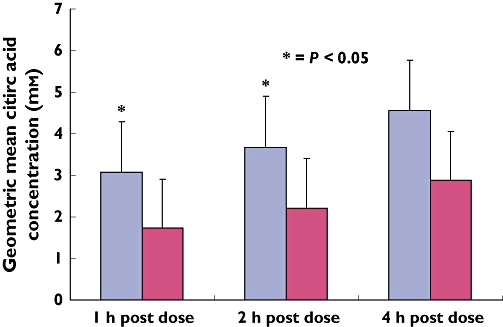

The concentration of citric acid provoking a mean of two coughs/inhalation (C2) from baseline was significantly (P < 0.05) increased at 1 h post dextromethorphan, compared with placebo, 0.48 mM (3.09) and 0.24 mM (1.74), respectively. A significant increase was also demonstrated at 2 h post dextromethorphan compared with placebo, 0.57 mM (3.75) and 0.34 mM (2.19), respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The geometric mean concentration difference in C2 from baseline (Dextromethorphan, ( ); placebo, (

); placebo, ( ))

))

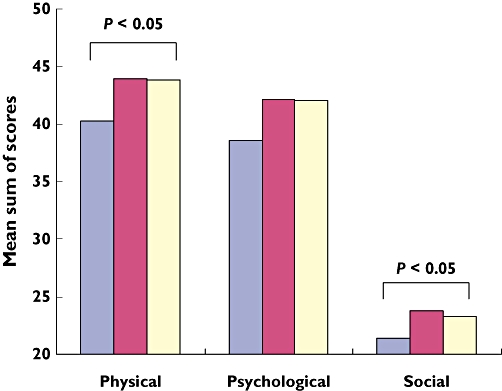

A further subjective measure of cough, the Leicester Cough Questionnaire showed no significant difference between placebo and dextromethorphan (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Leicester cough questionnaire scores (screening, ( ); Dextromethorphan, (

); Dextromethorphan, ( ); placebo, (

); placebo, ( ))

))

Discussion

In this study the assessment of the cough reflex with citric acid demonstrated a statistically significant and consistent decrease in sensitivity associated with dextromethorphan administration when compared with placebo. This robust drug effect is consistent with several other studies performed using citric acid cough challenge methodology in normal subjects [1–3, 7, 16, 17]. There can be little doubt that dextromethorphan in the preparation used alters the cough reflex sensitivity and this study shows that such a change in cough reflex and sensitivity can be demonstrated in a population with chronic cough. However, in all subjective measures of cough i.e. self assessed cough counts, the various diary record cough scores, the Leicester Cough Questionnaire, and Visual Analogue Score response of placebo and active were to all intents and purposes identical. This failure of subjective and pseudo-objective tests to detect any significant difference between active and placebo poses several questions.

One interpretation is that the well described placebo effect is so large in this population that any reduction in cough caused by the alteration of the cough reflex sensitivity via dextromethorphan administration was swamped by the massive placebo effects. Highly significant placebo responses have been previously demonstrated on numerous occasions in normal subjects [17] and in subjects with a respiratory tract infection and against other drugs such as codeine [18].

This phenomenon was observed in both our objective and subjective data. For example a mean reduction of 35.6% for diary symptom score was recorded during the placebo arm of the study. This was further reflected in the objective measure of cough sensitivity where following treatment with placebo C2 was reduced by 40%.

Our alternative hypothesis is that current subjective measures are very poor at accurately reflecting the outcome of antitussive drug effects. This speculation is, however, impossible to prove until objective cough recorders or similar devices are perfected. Even if true, it could be argued that subjective measures should be the primary endpoint of a symptomatic treatment and whether or not cough counts are objectively diminished may be irrelevant if the patient reports improving as much on placebo as on active treatment.

Finally, that there was such a clear and robust reduction in objective cough reflex sensitivity and that this did not translate into any impact on subjective measures calls into doubt the correlation between cough reflex sensitivity and the clinical phenomenon of cough. There is however, a large body of evidence supporting the assessment of cough reflex as an important indicator of clinical response [19]. Thus, the cough reflex is heightened in conditions associated with both acute and chronic cough. For example, it has been demonstrated that the log concentration of capsaicin required to elicit two coughs is significantly lower during infection than in the healthy state, whereas, methacholine values remain unchanged during infection compared with baseline [20]. This implies that upper respiratory infection may cause acute cough as a result of increased sensitivity of capsaicin sensitive afferent airway nerves without affecting airway calibre or responsiveness.

Finally, alteration of cough sensitivity has been demonstrated, resulting in a predisposition to cough. For example, cough is a recognized side-effect of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Captopril significantly shifts the dose–response curve to capsaicin inhalation in normal individuals implying a role for ACE in the cough reflex, possibly through metabolism of substrates other than angiotensin 1 [21].

Acknowledgments

Competing interests: DH is now, and when the work reported was conducted, in full-time employment with the Procter & Gamble Company. DH has shares in the company.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grattan TJ, Marshall AE, Higgins KS, Morice AH. The effect of inhaled and oral dextromethorphan on citric acid induced cough in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;39:261–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manap RA, Wright CE, Gregory A, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Meller ST, Kelm GR, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Morice AH. The antitussive effect of dextromethorphan in relation to CYP2D6 activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:382–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthys H, Bleicher B, Bleicher U. Dextromethorphan and codeine: objective assessment of antitussive activity in patients with chronic cough. J Int Med Res. 1983;11:92–100. doi: 10.1177/030006058301100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eccles R. The powerful placebo in cough studies? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:303–8. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2002.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruhle KH, Criscuolo D, Dieterich HA, Kohler D, Riedel G. Objective evaluation of dextromethorphan and glaucine as antitussive agents. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;17:521–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor JA, Novack AH, Almquist JR, Rogers JE. Efficacy of cough suppressants in children. J Pediatr. 1993;122(5 Pt 1):799–802. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parvez L, Vaidya M, Sakhardande A, Subburaj S, Rajagopalan TG. Evaluation of antitussive agents in man. Pulm Pharmacol. 1996;9:299–308. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J, Owen E, Earis J, Woodcock A. Effect of codeine on objective measurement of cough in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:831–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulrennan S, Wright C, Thompson R, Goustas P, Morice A. Effect of salbutamol on smoking related cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2004;17:127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, Singh SJ, Morgan MDL, Pavord ID. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) Thorax. 2003;58:339–43. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morice AH, Kastelik JA, Thompson R. Cough challenge in the assessment of cough reflex. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:365–75. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown BW., Jr The crossover experiment for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1980;36:69–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armitage P, Hills M. The two-period crossover trial. Statistician. 1982;31:119–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu G, Liang KY. Sample size calculations for studies with correlated observations. Biometrics. 1997;53:937–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senn SJ. Cross-Over Trials in Clinical Research. 2. Chichester: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karttunen P, Tukiainen H, Silvasti M, Kolonen S. Antitussive effect of dextromethorphan and dextromethorphan-salbutamol combination in healthy volunteers with artificially induced cough. Respiration. 1987;52:49–53. doi: 10.1159/000195303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rostami-Hodjegan A, Abdul-Manap R, Wright CE, Tucker GT, Morice AH. The placebo response to citric acid-induced cough: pharmacodynamics and gender differences. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:315–9. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freestone C, Eccles R. Assessment of the antitussive efficacy of codeine in cough associated with common cold. J Pharmacy Pharmacol. 1997;49:1045–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt D, Jorres RA, Magnussen H. Citric acid-induced cough thresholds in normal subjects, patients with bronchial asthma, and smokers. Eur J Med Res. 1997;2:384–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Connell F, Thomas VE, Studham JM, Pride NB, Fuller RW. Capsaicin cough sensitivity increases during upper respiratory infection. Respir Med. 1996;90:279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(96)90099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morice AH, Lowry R, Brown MJ, Higenbottam T. Angiotensin converting enzyme and the cough reflex. Lancet. 1987;2:1116–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]