Abstract

Natural killer T (NKT) cells constitute a distinct lymphocyte lineage at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity, yet their role in the immune response remains elusive. Whilst NKT cells share features with other conventional T lymphocytes, they are unique in their rapid, concomitant production of T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 cytokines upon T-cell receptor (TCR) ligation. In order to characterize the gene expression of NKT cells, we performed comparative microarray analyses of murine resting NKT cells, natural killer (NK) cells and naïve conventional CD4+ T helper (Th) and regulatory T cells (Treg). We then compared the gene expression profiles of resting and alpha-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)-activated NKT cells to elucidate the gene expression signature upon activation. We describe here profound differences in gene expression among the various cell types and the identification of a unique NKT cell gene expression profile. In addition to known NKT cell-specific markers, many genes were expressed in NKT cells that had not been attributed to this population before. NKT cells share features not only with Th1 and Th2 cells but also with Th17 cells. Our data provide new insights into the functional competence of NKT cells which will facilitate a better understanding of their versatile role during immune responses.

Keywords: transcriptomics, T helper cells, regulatory T cells, natural killer T cells, natural killer cells

Introduction

Natural killer T (NKT) cells constitute a unique lymphocyte population. Unlike conventional CD4+ T helper (Th) cells which are reactive to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-associated peptides expressed by antigen-presenting cells, NKT cells recognize lipids in the context of CD1d molecules.1–3 NKT cells are either CD4+ or CD4– CD8–, and express a skewed range of T-cell receptor (TCR) variable region genes and the natural killer (NK) cell marker NK1·1 (NKR-P1C). In mice, most NKT cells express an invariant Vα14-Jα18 TCR combined with a limited set of Vβ chains.4 Accordingly, these NKT cells5 have been termed invariant (i) NKT cells.6 These iNKT cells recognize alpha-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), the model glycosphingolipid antigen.2 Upon activation through TCR ligation, iNKT cells release abundant T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α as well as Th2 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10 and IL-13.7–10 Prompt and simultaneous expression of Th1 and Th2 cytokines by the same cell type is a hallmark of iNKT cells.

In fact, iNKT cells shape a wide range of immune responses: they control tissue destruction, autoimmunity, antitumour responses, host defence, allergy and inflammation.11–21 Accordingly, iNKT cell activation has both beneficial22–24 and harmful25,26 consequences. Such divergent responses may be attributed to their functional heterogeneity as well as their tissue distribution. However, the mechanisms determining the type of iNKT cell response and the cytokine profile determining the contribution of iNKT cells to immune responses remain elusive.

Analysis of gene expression patterns and genomic profiling have become useful tools for investigating the biological functions of distinct cell types and characterizing the functional profiles that distinguish a unique phenotype, or differentiation or activation stage. Comparative expression profiling reveals overlapping and unique signatures of distinct cell types and hence underlines differences and similarities between functionally related cell types or differentiation steps. We embarked on comparative analysis of the gene expression profiles of iNKT cells versus NK cells, conventional CD4+ T cells (Th, CD4+ CD25– cells), and regulatory T cells (Treg, CD4+ CD25+ cells) to obtain basic information about the functional competence of iNKT cells in innate and adaptive immune responses. Moreover, analysis of resting versus activated iNKT cells was undertaken in order to shed light on their functional plasticity during an immune response. Our findings reveal a unique gene expression profile of resting NKT cells in comparison to NK cells, Th cells and Treg cells, and multiple effector functions linking activated NKT cells not only to the known Th1 and Th2 phenotypes but also to the Th17 phenotype.

Materials and methods

Mice

We used 7- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 (H-2b) wild-type mice, and Vα14-Jα18 transgenic (tg) mice backcrossed (> 10 generations) on a C57BL/6 background.27,28 Mice were bred in our facility at the Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR) in Berlin and kept under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions in filter bonnet cages with food and water ad libitum. All experiments were conducted according to the German Animal Protection Law.

Antibodies

Antibodies against murine CD4 (clone RM4-5), Fas ligand (FasL) (clone K-10), IL-4 (clone 11B11), IFN-γ (clone R46A2), TNF-α (clone MP6-XT22), chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4) (clone 2B11), macrophage-1 antigen (CD11b/CD18) (Mac-1) (clone M1/70), B220 (clone RA3-6B2), CD11c (clone HL3) and CD8 (clone 53-6·7) were isolated from hybridoma cell lines. The CD1d/αGalCer tetramers were produced as previously described.29 Antibodies against murine NK1·1 (clone PK136), CD3 (clone 145-2C11), CD25 (clone PC61), lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) (clone M17/4) and streptavidin-PE-Cy7 were obtained from BD Bioscience (Heidelberg, Germany). The monoclonal antibody (mAb) against murine IL-17 (clone TC11-18H10·1) was obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA).

Isolation and purification of cells by magnetic antibody cell sorting (MACS) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Isolation of spleen and liver lymphocytes, red blood cell lysis and tetramer staining were performed as described elsewhere.30 MACS with MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol to enrich cell populations by positive selection. Subsequently, enriched cells were sorted using a FACS-Diva cell sorter (BD Bioscience). All manipulations were performed on ice. Viable cells were detected by staining with propidium iodide (PI) or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI). The purity of sorted fractions was verified by FACS analysis. At least 5 × 105 cells were isolated by FACS and further used for microarray analysis. FACS was repeated four times and duplicate samples of each sorted cell type were used for two independent microarray studies. To avoid gene expression resulting from handling and purification of cells, all procedures were performed at 4°. Moreover, to reduce the overall purification time, MACS enrichment preceded FACS. Furthermore, to avoid non-specific effects, we performed all incubations in the presence of blocking antibodies (anti-Fc receptor plus rat serum). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that these preparations might have impacted on the results, we consider the chances of this to be minimal. This is consistent with our observation that cells did not undergo general apoptosis, as indicated by the lack of apoptosis markers.

In vivo activation of NKT cells

NKT cell activation was performed by injecting a single dose of 2 µg of αGalCer intravenously (i.v.) into the tail vein. Mice were killed 1 hr later and spleen cells were isolated.

FACS analysis

To confirm microarray data at the protein level, flow cytometric analyses were performed as follows. Single cell suspensions were incubated with rat serum and anti-CD16/CD32 (anti-Fc receptor) mAb for 5 min at 4° to block non-specific antibody binding. Next, fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD1d/αGalCer tetramers were added and cultures were incubated for 50 min on ice in the dark on a rocking platform. Viable cells were detected by staining cells with PI or DAPI. The Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) was used for intracellular cytokine staining. Tetramers were prepared and loaded with lipids as described elsewhere.29

Preparation of RNA from single-cell suspensions

Total RNA was isolated by the TRIzol® Reagent RNA preparation method (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Briefly, cells were resuspended immediately after FACS in 500 µl of TRIzol®, shock frozen and stored at −80°. Cells were thawed and further processed for total RNA isolation as described by the manufacturer. The amount of RNA was determined by measurement of optical density at 260/280 nm and total RNA was purified by RNeasy (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA integrity and the amount of total RNA were measured with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

Microarray procedures, experimental design and analysis

Microarray experiments were performed as two-colour hybridizations. Total RNA was extracted from single-cell suspensions. An amount of 4 µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with an oligo-dT-T7-promotor primer in a fluorescent linear amplification reaction (Agilent Technologies) and cDNA was labelled with either cyanine 3-CTP or cyanine 5-CTP (NEB Life Science Products, Frankfurt, Germany) in a T7 polymerase amplification reaction according to the supplier's protocol. In order to compensate for specific effects of the dyes and to ensure statistically relevant data analysis, a colour-swap dye-reversal was performed.31 The RNA samples were labelled vice versa with the two fluorescent dyes (fluorescence reversal). After precipitation, purification and quantification with a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Kisker, Steinfurt, Germany), 1·25 µg of each labelled cRNA was mixed, fragmented and hybridized to an 8·4 K custom-made mouse array (AMADID 010646) according to the supplier's protocol (Agilent Technologies). Scanning of microarrays was performed at 5 µm resolution using a DNA microarray laser scanner (Agilent Technologies). Features were extracted with an image analysis tool version A.6.1.1 (Agilent feature extraction Software; Agilent Technologies) using default settings. Data analysis was carried out on the Rosetta Inpharmatics platform resolver version 5·0 (Seattle, WA). Ratio profiles were combined in an error-weighted fashion with resolver to create ratio experiments. A twofold change expression cut-off for ratio experiments was applied together with anticorrelation of ratio profiles rendering the microarray analysis set highly significant (P > 0·05), robust and reproducible. The microarray data discussed in this publication have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE6782.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA as described previously.32 SYBR® Green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) uptake in double-stranded DNA was measured using the ABI™ Prism 7900 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer pairs were designed using the primer 3 software (available at http://primer3.sourceforge.net). GAPDH was used as an internal control. Quantifications were performed at least twice with independent cDNA samples and in duplicate for each cDNA and primer pair. Possible contamination with genomic DNA was assessed using DNAse-digested, not reverse-transcribed, RNA as the template. Primer sequences are listed in Table S2 of the Supplementary Material.

Results

Transcriptome comparison of resting NKT cells with NK, conventional Th cells and Treg

To examine the cell type-specific characteristics of NKT cells, microarray studies compared RNA of resting NKT cells with that from naïve Th cells and Treg cells as well as NK cells. Initially, cells were stained with mAbs for characteristic surface markers, and then enriched and purified by MACS and sorted by FACS. NK cells were sorted as NK1·1+ CD3– cells and iNKT cells were isolated as NK1·1+ CD3+ CD1d/αGalCer tetramer+ cells. These cells will be referred to as NKT cells. Conventional Th cells and Treg cells were sorted as CD3+ CD4+ NK1·1– CD25− and CD3+ CD4+ NK1·1– CD25+, respectively.

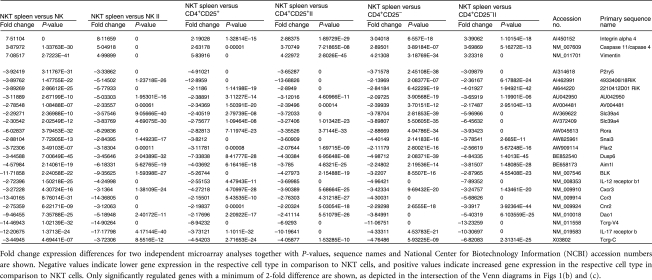

Microarray results of this first experimental set revealed several genes previously reported to be expressed by macrophages, suggesting minute contaminations of macrophages in the sorted NKT cell population. This was unexpected as FACS analysis of the sorted samples showed a purity of > 95% NKT cells. In order to improve the purity of the sorted NKT cells, we selectively excluded macrophages, B cells, CD8+ T cells and dendritic cells during MACS and FACS in the second experimental set. NKT cells were sorted as CD3+ NK1·1+ CD1d/αGalCer tetramer+ and Mac-1– B220– CD11c– CD8–. FACS analysis of purified cells revealed that NK cells were 99·5% pure and NKT cells were 96·5% pure (Fig. S1, Supplementary Material). In addition, Th cells and Treg cells were 98% and 97·8% pure, respectively (Fig. S1). NKT cell RNA was used as common reference RNA, i.e. gene expression levels in other cells were related to the levels detected in NKT cells. Therefore, genes were considered up-regulated when their expression was increased compared with NKT cells and down-regulated when their expression was decreased. To exclude erroneous detection of genes and to render microarray results more robust, two independent microarray analyses were performed. Only genes with P-values < 0·05 and a minimum twofold difference were considered significantly regulated and only genes correlated in both experimental sets were considered to be differentially regulated in the gene expression analyses of different cell types. Microarray results from the first set of experiments with initial sorting parameters were compared with those from the second set of experiments with improved sorting procedures (Fig. S2).

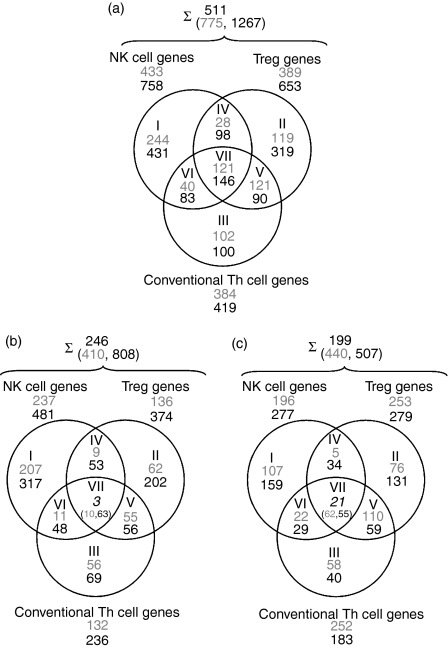

Comparison of the two microarray experiments revealed an intersection of 511 differentially regulated genes, with 775 genes in the first experimental set and 1267 genes in the second experimental set (Fig. 1a). A set union of 246 genes were up-regulated in NK cells, conventional Th cells or Treg cells as compared with NKT cells, i.e. down-regulated in NKT cells in both arrays. Amongst these genes, an intersection of three genes were uniquely down-regulated in NKT cells as compared with the other cell types (Fig. 1b). A set union of 199 genes were down-regulated in NK cells, conventional Th cells or Treg as compared with NKT cells, i.e. up-regulated in NKT cells in both arrays. An intersection of 21 genes were uniquely up-regulated in NKT cells as compared with all other cell types (Fig. 1c). Only correlated genes in both experimental sets were considered relevant and hence were used in further investigations.

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams of microarray results for natural killer T (NKT) cells compared with natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells compared with CD4+ CD25–[conventional T helper (Th)] cells, and NKT cells compared with CD4+ CD25+ cells [T regulatory cells (Treg)] from spleens of C57BL/6 mice. NKT cell RNA was used in all comparisons as a common reference. (a) A summary of the genes that are differentially expressed in the cell types described. (b) Up-regulated genes: up-regulated in all other cell types compared with NKT cells. (c) Down-regulated genes: down-regulated in all other cell types compared with NKT cells, i.e. up-regulated genes in NKT cells. Roman numerals represent the Venn diagram subsets, and Arabic numerals the number of genes: grey, results from the first experimental set; black, results from the second experimental set; italic, intersection of genes from both experiments that were up- or down-regulated in all other cell types compared with NKT cells. Accession numbers and fold change expression differences for listed genes are available in the online Supplementary material (Table S1). Numbers after the summation sign represent the intersection of differentially regulated genes of the first (grey) and second (black) experimental set. The upper number represents the intersection of differentially expressed genes in both experimental sets.

Unique gene expression of NKT cells

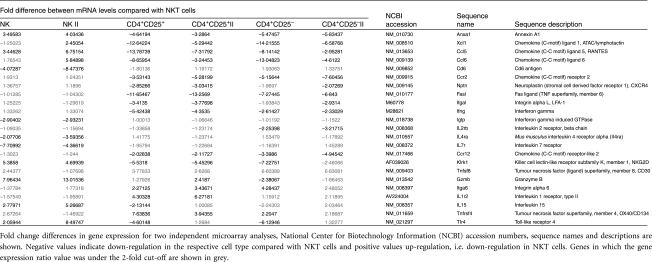

Genes differentially regulated in NK cells, conventional Th cells and Treg in comparison to NKT cells represent an NKT cell-specific expression signature. A high proportion of these genes encode cytokine and chemokine receptors (Table 1). Some of these molecules have already been associated with NKT cells, such as the IL-12 receptor β1, CXCR3 and integrin-α4β1 (very late antigen-4 (VLA-4)),33–35 although the latter was found to be expressed at the same levels on both human NK and NKT cells.33 Among the genes whose expression was uniquely up-regulated in resting NKT cells, B cell lymphocyte kinase (BLK), chemokine (C-C motif) receptor (CCR)3, IL-17RB, retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (ROR)α and d-amino acid oxidase (DAO)1 have not to date been attributed to this T-cell subset. BLK belongs to the family of B cell lymphoma (Bcl)-2 proteins, which regulate programmed cell death. BLK is proapoptotic and essential for initiation of programmed cell death and stress-induced apoptosis.36,37 The chemokine receptor CCR3 previously shown to be expressed by eosinophils and Th2 cells binds a variety of chemokines including RANTES and eotaxin.38 Despite elevated RNA expression, we did not detect CCR3 on the surface of NKT cells by FACS. The IL-17 receptor-B binds the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17, which is produced by a distinct T-cell population (Th17) upon activation.39–42 IL-17 also induces downstream production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and a number of proinflammatory cytokines ultimately leading to enhanced inflammation and neutrophil activation.39,40 RORα is a member of the steroid hormone nuclear receptor superfamily and can bind melatonin, which activates IL-2 production.43 Additionally, RORα is involved in lymphocyte development and regulation of cytokine production by innate immune cells and lymphocytes.44 DAO1 is an enzyme catalysing oxidative deamination of neutral d-amino acids with unknown function in T cells.45

Table 1.

Differentially regulated genes in natural killer T (NKT) cells compared with natural killer (NK) cells, conventional T helper (Th) cells and regulatory T cells (Treg)

|

Genes whose expression was enhanced in NK cells, Th cells and Treg compared with NKT cells included caspase 11, integrin-α4β1 and vimentin. Caspase 11 is a mediator of the septic shock response and is induced in various cell types upon proinflammatory stimulation.46 Integrin-α4β1 is important in cell migration and plays a central role in lymphopoiesis and inflammation-induced recruitment of leucocytes.47 Vimentin is required for lymphocyte rigidity and is involved in transendothelial migration.48 Thus, these genes describe the unique gene expression signature of NKT cells comprising a minimal set of genes differentially expressed in comparison to related lymphocyte populations (NK cells, Th cells and Treg).

Expression profile of NKT cells shared with NK cells, Th cells or Treg

A high number of genes were expressed in NKT cells as well as in one or more of the lymphocyte populations examined, namely NK cells, Th cells and Treg (Table 2). Accordingly, we focused our analysis on genes encoding soluble effector molecules, cytokines and chemokines, as well as membrane receptors. Genes with high expression levels in NKT cells and NK cells and low expression levels in Th cells and Treg were considered to reflect innate immune properties of NKT cells. The chemokine lymphotactin and the chemokine receptors CCR2, CXCR4, CCRL2 fall into this category, as well as FasL, LFA-1 (integrin-αL) and IFN-γ. Expression of annexin A1, natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D), RANTES and CCL6 was elevated in NK cells over NKT cells and lower in both Th cells and Treg.

Table 2.

Differentially regulated genes in natural killer T (NKT) cells compared with natural killer (NK) cells, conventional T helper (Th) cells or regulatory T cells (Treg)

|

Similar expression levels for NK and NKT cells, but increased expression in Th cells and Treg were detected for integrin-α6, CD30 and OX40. Genes similarly expressed by NKT cells and Th cells/Treg but with decreased expression in NK cells were considered to reflect the adaptive immune properties of NKT cells. These genes included CD6, interferon-inducible GTP-binding protein (IGTP), IL-4R and IL-7R. IL-15 was similarly expressed in NKT and Th cells but up-regulated in NK cells over NKT cells. As compared with NKT cells, type II IL-1 receptor expression was increased to a greater extent in Th cells than in NK cells and Treg, where expression was found to be similar. As expected, IL-2R gene expression in NK and Th cells was similar to that in NKT cells. Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 expression was strongest in NK cells and weakest in Th cells and Treg.

Transcriptome analysis of resting NKT cells versus activated NKT cells

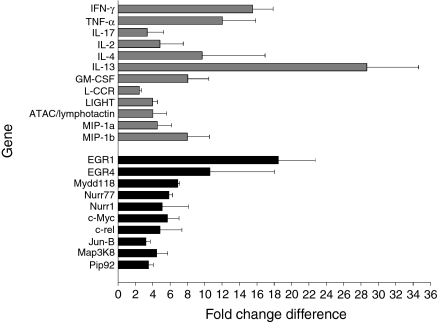

Although NKT cells perform a variety of diverse functions, the gene expression output as a result of NKT cell activation has not yet been studied. We compared gene expression of NKT cells before and after αGalCer activation in vivo. We detected 281 differentially regulated genes in activated NKT cells in the first microarray comparison and 76 genes differentially regulated in the second comparison. A set union of 38 genes were up-regulated and none was down-regulated in αGalCer-activated NKT cells in both comparisons (Fig. 3 and Table S1). Genes with increased expression can be classified into two groups.

Figure 3.

Genes with up-regulated expression in alpha-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)-activated natural killer T (NKT) cells compared with resting NKT cells. Fold change differences for genes found in two independent microarray analyses are shown. Grey bars, genes belonging to the group of cytokines and chemokines; black bars, genes belong to the group of cell cycle control and apoptosis-related genes. c-rel, cellular reticuloendotheliosis oncogene; EGR, early growth response; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; Jun-B, Jun-B oncogene; L-CCR, Lipopolysaccharide-inducible CC Chemokine Receptor; LIGHT, homologous to lymphotoxins, exhibits inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D for HVEM, a receptor expressed by T lymphocytes; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

The first group consisted of cytokines and chemokines with immunostimulatory and immunoregulatory properties. Indeed, IFN-γ, IL-13, TNF-α, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-4 were markedly up-regulated in activated NKT cells, namely 15-fold, 28-fold, 12-fold, 8-fold and 9-fold, respectively. Expression of lymphotactin and IL-17 were increased 4-fold or 3-fold, respectively. Moreover, genes encoding IL-2, L-CCR, LIGHT, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-1β also showed stronger expression in activated NKT cells. Thus, microarray results demonstrate that NKT cell activation results in production of a versatile chemokine and cytokine profile promoting Th1 (IFN-γ and TNF-α), Th2 (IL-13 and IL-4) and Th17 (IL-17) responses.

The second group of genes up-regulated in activated NKT cells comprised molecules involved in signal transduction, transcription factors and early response genes. The early growth response 1 (EGR1) transcriptional factor, which is rapidly induced in lymphocytes after activation and transduces proliferative and antiapoptotic signals,49 was up-regulated 18-fold in activated NKT cells. Growth arrest and DNA damage 45 (myeloid differentiation primary response gene 118) (Gadd45 (MyD118)), encoding an antiapoptotic molecule controlling growth arrest and the cell cycle,50 was up-regulated 7-fold. Moreover, cellular-myelocytomatosis oncogene (c-Myc), generally expressed in propagating cells controlling proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis,51 had 6-fold increased expression levels. We detected nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 1 (NR4A1) with 6-fold and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 8 (Map3K8) with 4-fold higher expression in NKT cells. Thus, NKT cells activated through their TCR rapidly gain the potential to produce various cytokines mediating a broad range of functions. Induction of genes encoding both cell cycle-controlling and antiapoptotic molecules suggests increased resistance to apoptosis and a tight control of cell proliferation.

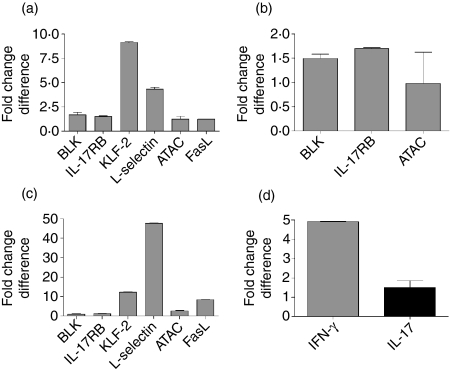

Our microarray results were verified by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Fig. 2), and surface expression of LFA-1, FasL and CXCR4 as well as intracellular expression of TNF-α, IL-4, IFN-γ and IL-17 was verified at the protein level by FACS analyses (data not shown). However, intracellular and surface expression of TLR4 by both resting and activated NKT cells could not be detected (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for selected genes identified by microarray analyses. Differences in gene expression are shown as delta-delta cycle threshold (ct). (a) Gene expression in natural killer T (NKT) cells versus conventional T helper (Th) cells. (b) Gene expression in NKT cells versus regulatory T cells (Treg). (c) Gene expression in NKT cells versus natural killer (NK) cells. (d) Gene expression in resting versus alpha-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)-activated NKT cells. Real-time qPCR was performed twice in triplicate and delta ct values were normalized to internal GAPDH expression. ATAC, activation-induced, T-cell-derived and chemokine-related; BLK, B-cell lymphocyte kinase; FasL, Fas ligand; IL, interleukin; KLF, Kruppel-like factor.

Discussion

Comparative global analysis of genes differentially expressed in NKT cells in comparison with related lymphocyte populations provided insights into the gene expression programme guiding the diverse functions and properties of this unique lymphocyte population. We observed a specific gene expression profile of NKT cells as well as a shared signature with lymphocytes of the innate and adaptive immune system. We found that proliferation of resting NKT cells is tightly controlled and that NKT cell activation leads to rapid induction of antiapoptotic genes and a versatile effector programme. Two recent publications described microarray studies with NKT cells.52,53 Lin et al. compared different activated NKT cell subsets52 and Yamagata et al. identified a common gene expression signature amongst innate lymphocytes.53 However, these studies did not compare the gene expression signature of NKT cells with those of NK cells, Th cells and Treg, nor did they compare resting and activated NKT cells.

We describe here a unique gene expression pattern of NKT cells comprising not only known markers of NKT cells but also genes not to date attributed to this peculiar T-cell subset. Many genes within this unique combination encode cytokines, chemokines and their receptors as well as proteins involved in cell cycle control and regulation of apoptosis (Table 1). NKT cells strongly expressed the receptors for IL-12 and IL-17 when compared with NK cells, Th cells and Treg. IL-12 has already been described in the context of NKT cell activation.54 In this context, an encounter with microbial invaders results in rapid NKT cell activation which is mediated by IL-12 produced by dendritic cells or macrophages. IL-17-producing Th cells have recently attracted great interest as a third distinct mediator of Th effector functions in addition to Th1/Th2 cells with ties to the Treg compartment.41,55 IL-17 receptor-B binds the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17, which induces production of mediators, for example IL-6 and IL-8, causing inflammation.56,57 Therefore, IL-17 has been suggested to be critical in various inflammatory responses including autoimmunity,58 where NKT cells are well-characterized regulators.11,59,60 Recently, Michel et al. identified a subpopulation of IL-17-producing cells within NKT cells.61 In fact, they demonstrated that, upon activation with αGalCer or bacteria-derived glycolipids in vitro, mainly NK1·1– NKT cells produced IL-17 instead of the classical IL-4 and IFN-γ.61 In addition, we observed IL-17 secretion by both NK1·1– and NK1·1+ NKT cells upon activation in vitro (data not shown). Hence, our data further strengthen the notion that IL-17 can be produced by NKT cells, probably depending on the presence of IFN-γ or IL-4 in the milieu.61 Moreover, expression of mRNA for both the IL-17 receptor and IL-17 by NKT cells could indicate a cell-autonomous autocrine activation loop, which pinpoints an as yet unrecognized function of NKT cells in inflammation. Whether the IL-17-mediated inflammation can be mediated by NKT cells alone or represents part of the Th17 cell-mediated response remains to be established. We detected the orphan nuclear receptor RORα as uniquely up-regulated in NKT cells. RORα directs differentiation of proinflammatory Th17 cells62 and functions in an iNKT cell lineage-specific manner.63 A central role of the transcription factor RORα in cerebellar development has been shown recently.64 To date, there are no data on the function of RORα in NKT cells. Further studies are required to clarify the role of RORα in NKT cells and Th17 cells.

As described previously, NKT cells express various chemokine receptors involved in their recruitment to the sites of action.34,65 This feature allows NKT cells to rapidly respond to external stimuli. The unique NKT cell expression pattern of both chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules resembles that of activated effector T cells.66,67 Decreased expression of l-selectin (CD62L) and vimentin indicates reduced trafficking to lymph nodes and the capacity for extravasation.48,68 Expression of LFA-1 on NKT cells is required for NKT cell homing to distinct tissue sites such as the liver.69 Most NKT cell lines show autoreactivity, and the cellular glycosphingolipid isoglobotriaosylceramide (iGb3) was described as an endogenous antigen for NKT cell activation.70 Thus, up-regulation of the proapoptotic gene BLK and down-regulation of antiapoptotic genes such as caspase 11 in resting NKT cells may constitute a mechanism by which any exacerbated NKT cell response would be rapidly shut down, thereby preventing the appearance of any immune pathology.

We detected marked up-regulation of genes controlling cell proliferation in activated versus resting NKT cells. Up-regulation of the antiapoptotic gene Gadd45/MyD118 was previously described in activated NKT cells and probably contributes to the resistance of NKT cells to apoptosis upon activation.71 Moreover, we detected elevated expression of EGR1, Map3K8, c-Myc and Nurr77 in activated NKT cells (Fig. 3 and Table S1). These genes are involved in regulation of apoptosis upon activation. EGR1 exhibits antiapoptotic properties.49–51,72,73 Up-regulation of these genes demonstrates stringent control of apoptosis in place to ensure survival and adequate NKT cell responses and underlines the idea that NKT cells do not undergo apoptosis after activation but are rather resistant to apoptosis and down-regulate their TCR upon stimulation.71,74,75

Microarray analysis of activated NKT cells revealed substantially increased expression of 10 different cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 3 and Table S1). Among them, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-13, TNF-α, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and lymphotactin were previously detected in αGalCer-activated NKT cells.34,71,76–80 IL-13 and MIP-1α were found in distinct NKT cell subsets. However, concomitant production of GM-CSF, IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-4 is characteristic, and a hallmark, of activated NKT cells. Genes with expression levels comparable between NKT cells and NK cells, Th cells or Treg characterize NKT cell properties as either innate or adaptive traits. Expression of genes encoding lymphotactin, CCL5, CCR2, CXCR4, FasL, LFA-1, IFN-γ, NKG2D, CD30 and granzyme B has previously been described for NKT cells (Table 2).34,67,69,78,81–85 Recent findings describing NKT cells as IL-17 producers add an intriguing new function to these versatile cells.61 The diversity of these genes demonstrates that NKT cells can perform diverse effector and regulator functions at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. Moreover, it appears that they are mostly regulated by environmental stimuli rather than by differentiation-associated expression programmes as described for conventional Th cells.

Concluding remarks

The global characterization of NKT cell properties reveals that resting NKT cells express proapoptotic genes to prevent activation and exaggerated autoreactivity in the absence of infection or inflammation. At this stage, NKT cells also express genes encoding various cytokine and chemokine receptors to promote their rapid activation. Upon activation through their TCR, NKT cells produce antiapoptotic- and apoptosis-regulating genes to ensure prolonged survival. This provides the basis for effector and regulatory functions as suggested by rapid gene expression of numerous cytokine and chemokine genes upon activation. Of note, we detected IL-17R and IL-17 gene expression by NKT cells. Hence the known spectrum of Th1- and Th2-like properties of NKT cells is further expanded to include Th17 functions. NKT cells are probably the most versatile cytokine producers of all T lymphocytes. One could speculate that their broad functional capacity is a characteristic of the evolutionarily conserved state of NKT cells, contrasting with functionally committed conventional T-cell subsets, which are determined by their state of differentiation. It remains to be established whether distinct subsets or multifunctional NKT cells are responsible for their multifunctional character.

Acknowledgments

SHEK and UES acknowledge financial support from the German Science Foundation (SFB 421). This work is part of the PhD thesis of MN.

Abbreviations

- αGalCer

alpha-galactosylceramide

- iNKT cell

invariant natural killer T cell

- Th

T helper (CD4+ CD25–)

- Treg

regulatory T cell (CD4+ CD25+)

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article:

Figure S1. Purity of the second experimental set of selected lymphocyte populations from C75BL/6 mice: NKT, NK, conventional Th and Treg cells. Upper left: sorted NKT cells. Upper right: sorted NK cells. Cells were stained with antibodies against CD3 and NK1.1 and CD1d/αGalCer tetramers. NKT cells were sorted as NK1.1+ and tetramer+ cells among CD3+ lymphocytes. NK cells were sorted as NK1.1+ and tetramer− cells among CD3− lymphocytes. Percentages of positive cells are indicated in the quadrants. Dead cells were excluded by PI staining and only viable cells were sorted. Lower left: sorted CD4+ CD25− T cells. Lower right: sorted CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Cells were stained with antibodies against CD3, CD4 and CD25. T cells were sorted as CD4+ and either CD25− or CD25+ cells among CD3+ lymphocytes. Percentages of positive cells are indicated in the quadrants. Dead cells were excluded by PI staining and only viable cells were sorted.

Figure S2. Correlation blots of log ratios deduced from 2 independent experimental sets of RNA from NKT cells, NK cells, CD4+ CD25− T cells (conventional Th) and CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg). Colour-swap dyereversal ratio profiles were combined in an error-weighted fashion (Rosetta Resolver) to create ratio experiments for the respective experimental sets and the two experimental sets were compared by using the Rosetta Resolver “compare function” to decide how similar or dissimilar they were. Correlated signatures are depicted in yellow and anti-correlated signatures are depicted in pink. Ratios shown in blue were unchanged between both sets and red or green ratios were only present in set 1 or set 2, respectively.

Table S1. Genes upregulated in activated NKT cells. Depicted are fold change expression differences measured in 2 independent microarray analyses (Sort I and Sort II), P values, sequence names, NCBI accession numbers and names of the genes. With the exception of IL17 in Sort II only highly significant identified genes with P < 0·05 and with a minimum of 2-fold change in expression were considered to be regulated.

Table S2. Primer sequences for real-time qPCR. The NCBI accession numbers, the primer sequences and the primer names are depicted, whereby the extensions Fwd and Rev denote the forward and reverse primers for given genes.

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/.

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Spada FM, Koezuka Y, Porcelli SA. CD1d-restricted recognition of synthetic glycolipid antigens by human natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1529–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brossay L, Chioda M, Burdin N, Koezuka Y, Casorati G, Dellabona P, Kronenberg M. CD1d-mediated recognition of an alpha-galactosylceramide by natural killer T cells is highly conserved through mammalian evolution. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1521–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skold M, Faizunnessa NN, Wang CR, Cardell S. CD1d-specific NK1.1+ T cells with a transgenic variant TCR. J Immunol. 2000;165:168–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emoto M, Kaufmann SH, Liver NKT. cells. an account of heterogeneity. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:364–9. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond KJ, Pelikan SB, Crowe NY, et al. NKT cells are phenotypically and functionally diverse. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3768–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3768::AID-IMMU3768>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. NKT cells and tumor immunity – a double-edged sword. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:459–60. doi: 10.1038/82698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Paul WE. Cultured NK1.1+ CD4+ T cells produce large amounts of IL-4 and IFN-gamma upon activation by anti-CD3 or CD1. J Immunol. 1997;159:2240–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendiratta SK, Martin WD, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godfrey DI, Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. NKT cells: facts, functions and fallacies. Immunol Today. 2000;21:573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbari O, Stock P, Meyer E, et al. Essential role of NKT cells producing IL-4 and IL-13 in the development of allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2003;9:582–8. doi: 10.1038/nm851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan WL, Pejnovic N, Liew TV, Lee CA, Groves R, Hamilton H. NKT cell subsets in infection and inflammation. Immunol Lett. 2003;85:159–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, et al. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278:1623–6. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. CD1-specific T cells in microbial immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:471–8. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emoto M, Emoto Y, Buchwalow IB, Kaufmann SH. Induction of IFN-gamma-producing CD4+ natural killer T cells by Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette Guerin. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:650–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<650::AID-IMMU650>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakai T, Naidenko OV, Iijima H, Kronenberg M, Koezuka Y. Syntheses of biotinylated alpha-galactosylceramides and their effects on the immune system and CD1 molecules. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1836–41. doi: 10.1021/jm990054n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seino KI, Fukao K, Muramoto K, et al. Requirement for natural killer T (NKT) cells in the induction of allograft tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2577–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041608298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonoda KH, Faunce DE, Taniguchi M, Exley M, Balk S, Stein-Streilein J. NK T cell-derived IL-10 is essential for the differentiation of antigen-specific T regulatory cells in systemic tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;166:42–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. Immunoregulatory T cells in tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Kaer L. Natural killer T cells as targets for immunotherapy of autoimmune diseases. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behar SM, Dascher CC, Grusby MJ, Wang CR, Brenner MB. Susceptibility of mice deficient in CD1D or TAP1 to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1973–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuchi A, Nieda M, Schmidt C, et al. In vitro anti-tumour activity of alpha-galactosylceramide-stimulated human invariant Valpha24+ NKT cells against melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:741–6. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. Natural killer-like nonspecific tumor cell lysis mediated by specific ligand-activated Valpha14 NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5690–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duarte N, Stenstrom M, Campino S, Bergman ML, Lundholm M, Holmberg D, Cardell SL. Prevention of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice mediated by CD1d-restricted nonclassical NKT cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3112–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HY, Kim HJ, Min HS, Kim S, Park WS, Park SH, Chung DH. NKT cells promote antibody-induced joint inflammation by suppressing transforming growth factor beta1 production. J Exp Med. 2005;201:41–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moodycliffe AM, Nghiem D, Clydesdale G, Ullrich SE. Immune suppression and skin cancer development: regulation by NKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:521–5. doi: 10.1038/82782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendelac A, Hunziker RD, Lantz O. Increased interleukin 4 and immunoglobulin E production in transgenic mice overexpressing NK1 T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1285–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emoto M, Yoshizawa I, Emoto Y, Miamoto M, Hurwitz R, Kaufmann SH. Rapid development of a gamma interferon-secreting glycolipid/CD1d-specific Valpha14+ NK1.1– T-cell subset after bacterial infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5903–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00311-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda JL, Naidenko OV, Gapin L, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Wang CR, Koezuka Y, Kronenberg M. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;192:741–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kursar M, Bonhagen K, Kohler A, Kamradt T, Kaufmann SH, Mittrucker HW. Organ-specific CD4+ T cell response during Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2002;168:6382–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Churchill GA. Fundamentals of experimental design for cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 2002;32(Suppl.):490–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobsen M, Schweer D, Ziegler A, et al. A point mutation in PTPRC is associated with the development of multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2000;26:495–9. doi: 10.1038/82659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franitza S, Grabovsky V, Wald O, et al. Differential usage of VLA-4 and CXCR4 by CD3+CD56+ NKT cells and CD56+CD16+ NK cells regulates their interaction with endothelial cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1333–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim CH, Butcher EC, Johnston B. Distinct subsets of human Valpha24-invariant NKT cells: cytokine responses and chemokine receptor expression. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:516–9. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1121–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coultas L, Bouillet P, Stanley EG, Brodnicki TC, Adams JM, Strasser A. Proapoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bik/Blk/Nbk is expressed in hemopoietic and endothelial cells but is redundant for their programmed death. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1570–81. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1570-1581.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hegde R, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Blk, a BH3-containing mouse protein that interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, is a potent death agonist. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7783–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamkhioued B, Abdelilah SG, Hamid Q, Mansour N, Delespesse G, Renzi PM. The CCR3 receptor is involved in eosinophil differentiation and is up-regulated by Th2 cytokines in CD34+ progenitor cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:537–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolls JK, Linden A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity. 2004;21:467–76. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaffen SL, Kramer JM, Yu JJ, Shen F. The IL-17 cytokine family. Vitam Horm. 2006;74:255–82. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)74010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity. 2006;24:677–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakae S, Saijo S, Horai R, Sudo K, Mori S, Iwakura Y. IL-17 production from activated T cells is required for the spontaneous development of destructive arthritis in mice deficient in IL-1 receptor antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5986–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1035999100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerrero JM, Pozo D, Garcia-Maurino S, Osuna C, Molinero P, Calvo JR. Involvement of nuclear receptors in the enhanced IL-2 production by melatonin in Jurkat cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dzhagalov I, Zhang N, He YW. The roles of orphan nuclear receptors in the development and function of the immune system. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1:401–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konno R, Oowada T, Ozaki A, Iida T, Niwa A, Yasumura Y, Mizutani T. Origin of d-alanine present in urine of mutant mice lacking d-amino-acid oxidase activity. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:G699–703. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.4.G699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang SJ, Wang S, Kuida K, Yuan J. Distinct downstream pathways of caspase-11 in regulating apoptosis and cytokine maturation during septic shock response. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1115–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivera-Nieves J, Olson T, Bamias G, et al. 1-selectin, alpha 4 beta 1, and alpha 4 beta 7 integrins participate in CD4+ T cell recruitment to chronically inflamed small intestine. J Immunol. 2005;174:2343–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown MJ, Hallam JA, Colucci-Guyon E, Shaw S. Rigidity of circulating lymphocytes is primarily conferred by vimentin intermediate filaments. J Immunol. 2001;166:6640–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adamson ED, Mercola D. Egr1 transcription factor: multiple roles in prostate tumor cell growth and survival. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:93–102. doi: 10.1159/000059711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mak SK, Kultz D. Gadd45 proteins induce G2/M arrest and modulate apoptosis in kidney cells exposed to hyperosmotic stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39075–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunner T, Martin SJ. c-Myc: where death and division collide. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:456–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin H, Nieda M, Hutton JF, Rozenkov V, Nicol AJ. Comparative gene expression analysis of NKT cell subpopulations. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:164–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamagata T, Benoist C, Mathis D. A shared gene-expression signature in innate-like lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:52–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Weaver CT. Expanding the effector CD4 T-cell repertoire: the Th17 lineage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stamp LK, James MJ, Cleland LG. Interleukin-17: the missing link between T-cell accumulation and effector cell actions in rheumatoid arthritis? Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2004.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iwakura Y, Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1218–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI28508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schnyder-Candrian S, Togbe D, Couillin I, et al. Interleukin-17 is a negative regulator of established allergic asthma. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2715–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meyer EH, Goya S, Akbari O, et al. Glycolipid activation of invariant T cell receptor+ NK T cells is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity independent of conventional CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michel ML, Keller AC, Paget C, et al. Identification of an IL-17-producing NK1.1neg iNKT cell population involved in airway neutrophilia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:995–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bezbradica JS, Hill T, Stanic AK, Van Kaer L, Joyce S. Commitment toward the natural T (iNKT) cell lineage occurs at the CD4+8+ stage of thymic ontogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5114–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408449102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Serra HG, Duvick L, Zu T, et al. RORalpha-mediated Purkinje cell development determines disease severity in adult SCA1 mice. Cell. 2006;127:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johnston B, Kim CH, Soler D, Emoto M, Butcher EC. Differential chemokine responses and homing patterns of murine TCR alpha beta NKT cell subsets. J Immunol. 2003;171:2960–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human V(alpha) 24 natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:637–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J Exp Med. 2002;195:625–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galkina E, Tanousis K, Preece G, et al. 1-selectin shedding does not regulate constitutive T cell trafficking but controls the migration pathways of antigen-activated T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1323–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Emoto M, Mittrucker HW, Schmits R, Mak TW, Kaufmann SH. Critical role of leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 in liver accumulation of CD4+ NKT cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:5094–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou D, Mattner J, Cantu C 3rd, et al. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306:1786–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harada M, Seino K, Wakao H, et al. Down-regulation of the invariant Valpha14 antigen receptor in NKT cells upon activation. Int Immunol. 2004;16:241–7. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rajpal A, Cho YA, Yelent B, et al. Transcriptional activation of known and novel apoptotic pathways by Nur77 orphan steroid receptor. Embo J. 2003;22:6526–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beinke S, Robinson MJ, Hugunin M, Ley SC. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the TPL-2/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is regulated by IkappaB kinase-induced proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9658–67. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9658-9667.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crowe NY, Uldrich AP, Kyparissoudis K, et al. Glycolipid antigen drives rapid expansion and sustained cytokine production by NK T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:4020–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seino K, Harada M, Taniguchi M. NKT cells are relatively resistant to apoptosis. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:219–21. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mi QS, Meagher C, Delovitch TL. CD1d-restricted NKT regulatory cells: functional genomic analyses provide new insights into the mechanisms of protection against Type 1 diabetes. Novartis Found Symp. 2003;252:146–60. [discussion 60–4; 203–10] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Baron JL, Sidobre S, Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Locksley RM, Kronenberg M. Mouse V alpha 14i natural killer T cells are resistant to cytokine polarization in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332805100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leite de Moraes MC, Herbelin A, Gouarin C, Koezuka Y, Schneider E, Dy M. Fas/Fas ligand interactions promote activation-induced cell death of NK T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;165:4367–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fuss IJ, Heller F, Boirivant M, et al. Nonclassical CD1d-restricted NK T cells that produce IL-13 characterize an atypical Th2 response in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1490–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI19836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang S, Game DS, Davies D, Lombardi G, Lechler RI. Activated CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells secrete IL-2: innate help for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells? Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1193–200. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Faunce DE, Stein-Streilein J. NKT cell-derived RANTES recruits APCs and CD8+ T cells to the spleen during the generation of regulatory T cells in tolerance. J Immunol. 2002;169:31–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kennedy J, Vicari AP, Saylor V, Zurawski SM, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Zlotnik A. A molecular analysis of NKT cells: identification of a class-I restricted T cell-associated molecule (CRTAM) J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:725–34. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Sidobre S, Kieper WC, Tan JT, Ceredig R, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. Homeostasis of V alpha 14i NKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:966–74. doi: 10.1038/ni837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Metelitsa LS, Weinberg KI, Emanuel PD, Seeger RC. Expression of CD1d by myelomonocytic leukemias provides a target for cytotoxic NKT cells. Leukemia. 2003;17:1068–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tao J, Shelat SG, Jaffe ES, Bagg A. Aggressive Epstein-Barr virus-associated, CD8+, CD30+, CD56+, surface CD3–, natural killer (NK)-like cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:111–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]