Abstract

Human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), which are T-cell receptor αβ+ CD8+ T cells located between epithelial cells (ECs), are likely to participate in the innate immune response against colon cancer. IELs demonstrate spontaneous cytotoxic (SC) activity specifically directed against EC tumours but not against other solid tumour types. The aim of this study was to dissect out the mechanism of SC activity, focusing on the interaction of NKG2D on IELs with its ligands [major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I chain-related protein (MIC) and UL16 binding protein (ULBP)] found mainly on EC tumours. A novel series of events occurred. The NKG2D–MIC/ULBP interaction induced Fas ligand (FasL) production and FasL-mediated SC activity against HT-29 cells and MIC-transfectants. Tumour necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ, produced independently of this interaction, promoted SC activity. The immune synapse was strengthened by the interaction of CD103 on IELs with E-cadherin on HT-29 cells. Neither T-cell receptor nor MHC class I was involved. While the HT-29 cells were destroyed by soluble FasL, tumour necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ, the IELs were resistant to the effects of these mediators and to FasL expressed by the HT-29 cells. This unidirectional FasL-mediated cytotoxicity of IELs against HT-29 cells, triggered through NKG2D, is unique and is likely to be a property of those CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes that phenotypically resemble IELs.

Keywords: colonic adenocarcinoma, cytotoxicity, intraepithelial lymphocytes, major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related protein, NKG2D

Introduction

Human intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) are mainly T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ+ CD8+ T cells interspersed between intestinal epithelial cells (ECs). They are likely to be a first-line innate host defence against dysplastic or malignant ECs. This is suggested by the similarity in phenotype of IELs with that of CD8+ T cells in tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Both express CD44, CD45RO, CD69, CD122 and CD103, generally with few CD28+ or CD56+ cells.1,2 The present study shows that IELs, like TILs and memory CD8+ T cells, lack spontaneous perforin-mediated cytotoxicity.3 This lack of function by TILs, rather than being the result of defective lymphocytes or suppression by the tumour,4,5 may instead represent the natural behaviour of these cells, especially if they are derived from IELs. The presence of CD8+ T cells in the tumour can be a good prognostic indicator suggesting that they have a functional role in situ.6

Natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes can target tumour cells through NKG2D, a molecule that recognizes major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I chain-related (MIC) A and B proteins and UL16 binding proteins (ULBP) on ECs.7 The MIC proteins are found predominantly in the gastrointestinal epithelium, located on villous rather than crypt ECs. This may contribute to the routine death of villous ECs, making way for the maturing crypt ECs that push their way up the crypt-to-villus axis.8,9 NKG2D has been shown to have a particularly important role in antitumour immunity.10 The promiscuous binding of NKG2D to several ligands permits a broad array of tumour cells to be recognized, some of which lack one or more of these ligands.11,12

Effector cells have mechanisms that kill tumours, while the tumours, in turn, possess evasion tactics. Effector cells produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ) when contacting tumour cells, which up-regulates Fas expression on the cancer, an effect that is absent in IFN-γ knockout mice.13,14 Additionally, IFN-γ can promote susceptibility of the tumour to lysis by up-regulating the pro-apoptotic protease, caspase 1.15 Membrane- or microvesicle-bound Fas ligand (FasL) on the effector cells then triggers tumour cell apoptosis through Fas. At the same time, tumours have evasion tactics so as to avoid destruction. They protect themselves by releasing soluble MIC and ULBP.16,17 Expression of MIC on the tumour is reduced, while free MIC down-regulates NKG2D on TILs, impairing tumour-specific immunity. In addition, secretion of tumour-derived transforming growth factor-β1 stimulates tumour growth and reduces NKG2D display on the effector cells.18 Furthermore, tumours may counterattack effector cells through functional FasL.19

Human IELs show spontaneous cytotoxic (SC) activity specifically directed against EC tumours.20 They target adenocarcinomas from colon, pancreas or bladder, but not malignant melanoma, choriocarcinoma, or K562 cells, suggesting that the SC activity is EC specific. The main effector IELs are CD8+ CD16– CD56– T cells, rather than the small population of NK cells representing less than 10% of the whole. SC activity requires binding of CD103 on IELs to E-cadherin on ECs.21 The mechanism of SC activity is unknown but may involve perforin, granzyme B, FasL, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), found preformed in IELs.22

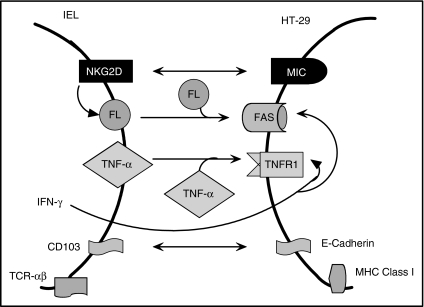

SC activity may be an essential innate host defence against colon cancer, as suggested by the phenotypic resemblance of IELs and CD8+ TILs. The aim of this study was to delineate the steps in effector–tumour cell contact that leads to cytotoxicity of the tumour, focusing on the role of NKG2D (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

This diagram depicts the interactions between IELs and HT-29 cells. The binding of NKG2D with MIC induces FasL production and cytotoxicity. TNF-α additively contributes to the cytotoxicity. IFN-γ optimizes the response by up-regulating Fas and TNFR1 expression on the target cell. CD103 and E-cadherin promote effector–target cell binding while TCR and MHC class I are outside the immunological synapse.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of lymphocytes

IELs were separated from the jejunal mucosa from otherwise healthy patients undergoing gastric bypass operations for morbid obesity after informed consent. Minced mucosa was treated in a shaking water bath (37°) for 60 min with 1 mm dithiothreitol diluted in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, glutamine and antibiotic–antimycotic solution (called ‘complete medium’) (all from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The mucosa was then treated in a shaking water bath at 37° with 0·75 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Sigma Aldrich), washed every 45 min with calcium-free and magnesium-free Hanks' balanced salt solution (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD), for three cycles. All cells in the supernatants were collected and separated by a 60% and 40% Percoll gradient (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) with 100% Percoll containing 9 parts Percoll and 1 part 10 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The IELs, which settled over the 40% solution, were collected. Any preparation containing < 85% lymphocytes was discarded. After isolation, the viability of IELs was 100% by trypan blue exclusion and remained > 95% after an 18-hr culture in complete medium at 37°.

Functional assays

Lymphocytes were cultured for 4 or 18 hr with target cells: Jurkat, WEHI, P815, HT-29, SW480, and LOVO cells (all from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) as well as MIC-transfected and control-transfected CIR cells, which have been described previously.23 In some experiments, colon cancer lines were first treated with 10 ng/ml IFN-γ (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 18 hr to augment their susceptibility to lysis by IELs. Redirected lysis using P815 cells was triggered by anti-CD3 antibody (50 ng/ml). All target cells were labelled with sodium chromate (Na51CrO7; New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) as detailed previously.20 The percentage cytotoxicity is the specific release of [51Cr] sodium chromate determined as follows: % cytotoxicity = (test value – spontaneous release) / (maximal release – spontaneous release). The following were either added to the assay or used to pretreat cells using optimal doses (which were determined in preliminary experiments): ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA, 2 mm), brefeldin A (5 μm), concanamycin A (100 nm), actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) or cycloheximide (5 μg/ml) (all from Sigma Aldrich). The monoclonal antibodies, CD178 (FasL) or CD103, as well as antibodies against the following were added at 5 μg/ml: MIC A protein (MICA; from Coulter-Immunotech, Miami FL, and from V. Groh), E-cadherin (from R & D Systems), TNF-α (Sigma Aldrich), TRAIL (R & D Systems), MHC class I (R & D Systems), and ULBP 1, 2 and 3 (kind gifts from Immunex, Seattle, WA). Isotype control immunoglobulin G (IgG) was added at 5–20 μg/ml depending upon the numbers of antibodies added to the test cultures. Soluble FasL, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were each used at 10 ng/ml, a dose which induced maximal cytotoxicity of HT-29 cells in preliminary experiments (R & D Systems).

Production of FasL, TNF-α, and IFN-γ was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R & D Systems). Removal of the CD94+ IELs was performed by antibody tagging followed by removal of the positive cells with magnetic beads coated with goat anti-mouse IgG (Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA).

In some experiments, serine esterase release was detected using the N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-lysine thiobenzyl ester (BLT; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) assay. In brief, IELs were cultured for 18 hr with or without HT-29 cells in medium lacking phenol red and the supernatants were collected. To each sample was added 0·2 mm 5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (Sigma) and 0·2 mm BLT in PBS. During the 45-min incubation in the dark, granzymes in each sample cleave BLT, causing a yellow colour that can then be quantified by absorbance measurements at 410 nm after subtraction of background.

Flow cytometry

Surface markers were labelled by indirect immunofluorescence using the monoclonal antibodies listed above. This was followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Cappel, West Chester, PA). Fluorescence was detected by a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer and expressed as relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) or the fold-increase in intensity of staining compared to an IgG–FITC or IgG–phycoerythrin control.

Statistical analysis

For two data sets, the Mann–Whitney test or paired Student's t-test was used depending on the distribution of the data. For groups of data, analysis of variance (anova) was used with the Tukey test to compare pairs within the groups.

Results

MIC induces FasL-mediated lysis

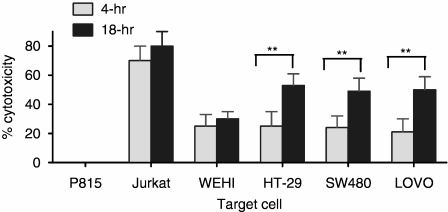

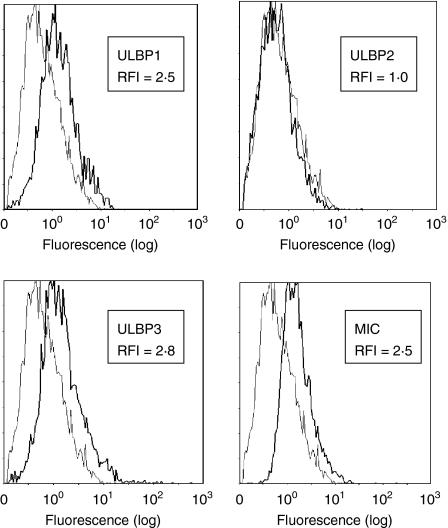

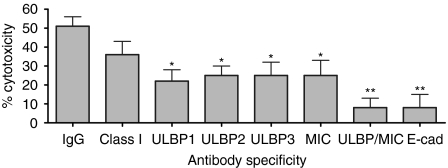

The SC activity by IELs was tested against several colon cancer cell lines as well as against Jurkat and WEHI cells. An 18-hr incubation was chosen because cytotoxicity of the colon cancer lines increased, perhaps providing the time for sequences of events to occur (Fig. 2). All IELs express NKG2D and the degree of expression (RFI of 2·4) did not change when incubated with HT-29 cells for 18 hr (not shown). The expression of ligands for NKG2D on tumour cells has been shown to promote their lysis by NK cells and naive CD8+ T cells,11,12 potentially serving an essential role in antitumour immunity.10 To evaluate this with IELs, a colonic adenocarcinoma cell model, the HT-29 cells, was used. These cells express NKG2D ligands, particularly ULBP1, ULBP3 and MICA, with little ULBP2 (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The role of the MIC/ULBP interaction in SC activity directed against HT-29 cells was evaluated by blocking the NKG2D ligands with specific antibodies. Blocking each ligand reduced cytotoxicity from a baseline of 45% to 23–26% with antibodies against each ULBP, even that against ULBP2, of which expression was minimal (Fig. 4). Antibody inhibition of three of the four ligands reduced lysis by similar amounts ranging from 20% to 28%. When all ligands were blocked, however, cytotoxicity was markedly reduced to 5% (an 88% decline); indicating that SC involved NKG2D ligands and that all needed to be disarmed to fully arrest cytotoxicity.

Figure 2.

IELs were cultured with radiolabelled target cells for 4 or 18 hr as listed, and the percentage cytotoxicity was determined. HT-29, SW480 and LOVO cells were pretreated with IFN-γ. The significant difference was determined by the paired Student's t-test (**P < 0·01).

Figure 3.

This flow cytometric analysis depicts the expression of NKG2D ligands on HT-29 cells. The lighter line is the isotype control. The RFI (defined in the Materials and methods) is shown for each marker.

Table 1.

Marker expression on target cells (with or without IFN-γ)

| HT-29 cells | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody specificity | No IFN-γ | IFN-γ | LOVO IFN-γ | SW480 IFN-γ | CIR-MIC No IFN-γ | JURKAT No IFN-γ | WEHI No IFN-γ |

| Fas | 2·2 | 4·4 | 4·1 | 3·9 | 2·1 | 10·0 | 1·2 |

| TNF R1 | 1·2 | 1·8 | 1·9 | 1·7 | 1·2 | 1·5 | 5·2 |

| E-cadherin | 1·9 | 2·2 | 2·1 | 2·0 | 1·0 | 1·0 | 1·0 |

| MICA | 1·9 | 2·5 | 1·5 | 2·0 | 5·5 | 5·0 | 1·1 |

| ULBP 1 | 1·5 | 2·5 | 1·8 | 2·2 | 1·0 | 1·0 | 1·0 |

| ULBP 2 | 1·2 | 1·0 | 1·2 | 1·4 | 1·0 | 1·0 | 1·0 |

| ULBP 3 | 1·6 | 2·8 | 1·9 | 2·3 | 1·0 | 1·0 | 1·0 |

Target cells, treated or not with IFN-γ, as listed at the top of the table, were stained by immunofluorescence for the markers listed to the left. RFI was the fold-increase in fluorescence compared to the GAM-FITC control, where 1·0 represents no heightened staining.

Figure 4.

IELs were cultured for 18 hr with radiolabelled IFN-γ-pretreated HT-29 cells in the presence of antibodies against MHC class I (‘Class I’), the NKG2D ligands, or E-cadherin (‘E-cad’). The value labelled ‘ULBP/MIC’ included antibodies against all three ULBP and that against MIC. Cytotoxicity was determined as described in the Materials and methods. Those values marked with asterisks are significantly less than control values with IgG according to anova (*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01).

Two other colonic adenocarcinoma cell lines with intermediate and low levels of NKG2D ligands (Table 1), the SW280 and LOVO cells,11,12 were also tested. IELs killed these cell lines to the same degree as HT29 cells (Fig. 2). Cytotoxicity declined by 79 ± 10% and 72 ± 8%, respectively, when all ligands were blocked, indicating that engagement of NKG2D on IELs with even low-density ligands was enough to trigger lysis (not shown). Attempts were made to create colon cancer lines lacking MIC/ULBP from fresh specimens without success. Previous publications also reported no MIC/ULBP-negative cells.11,12

Inhibiting MHC class I caused a non-significant reduction in SC activity (Fig. 4), suggesting that the TCR–MHC class I interaction was outside the immunological synapse and that SC activity was not antigen-driven. In addition, removal of the CD94+ IELs had little effect on SC activity, suggesting that the CD94–human leucocyte antigen-E interaction was not a major receptor/ligand system involved (46 ± 10% lysis with and 44 ± 8% lysis without CD94+ IELs). Instead, SC activity depended upon CD103 on IELs binding E-cadherin on the EC tumours21 (Fig. 4). Thus, two epithelial cell-specific interactions—NKG2D with MIC/ULBP and CD103 with E-cadherin—were required for optimal cytotoxicity of EC tumour targets.

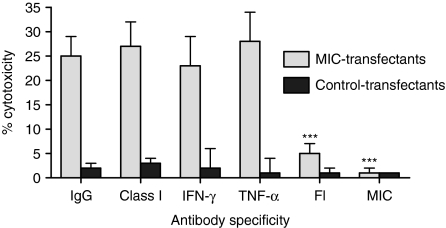

To determine the role of MIC in mediating SC activity, radiolabelled MIC-transfected or control-transfected CIR cells were cultured for 18 hr with IELs, and the cytotoxicity was measured (Fig. 5). IELs killed the MIC-transfected cells but not the control-transfected cells. Importantly, this activity was nearly eliminated by blocking MIC or FasL, but not by blocking MHC class I, IFN-γ, or TNF-α using specific antibody. This suggested that MIC-induced cytotoxicity was mediated through FasL.

Figure 5.

IELs were cultured for 18 hr with radiolabelled MIC or control transfectants in the presence of antibodies against MHC class I, IFN-γ, TNF-α, FasL, or MIC. The percentage cytotoxicity is shown. Those values marked with asterisks are significantly less than control values with IgG according to anova (***P < 0·001).

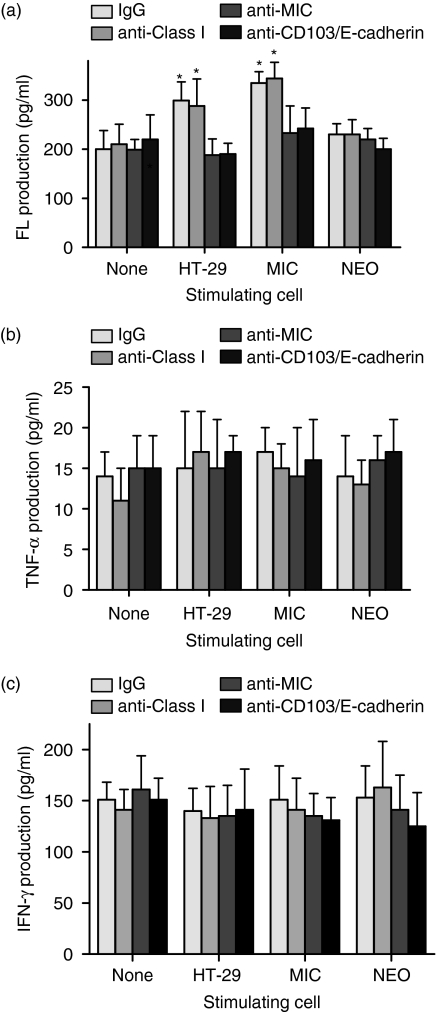

Production of FasL by IELs was measured after culture with HT-29 cells or MIC/control-transfected CIR cells. Protein expression by ELISA was used rather than intracellular FasL because the latter was undetectable. The target cells were pretreated with actinomycin D so that release of FasL was consistently less than 25 pg/ml (Fig. 6). The rise in FasL with HT-29 cells was inhibited, not just by blocking MIC, but also by inhibiting the CD103/E-cadherin interaction. The rise in FasL with MIC-transfectants was reduced only by blocking MIC. This showed that MIC could stimulate FasL release in the absence of the CD103/E-cadherin interaction. Production of TNF-α and IFN-γ by IELs, in contrast, was not up-regulated by exposure to HT-29 cells or MIC transfectants nor was it affected by blocking MIC, indicating that the NKG2D–MIC interaction promoted production of FasL but not of TNF-α or IFN-γ.

Figure 6.

IELs were cultured for 18 hr alone or with actinomycin-pretreated HT-29 cells or the MIC- or control (NEO)-transfected CIR cells in the presence of antibodies. The production of (a) FasL, (b) TNF-α, and (c) IFN-γ is shown. Those values marked with asterisks are significantly greater than the values with no stimulating cell according to anova (*P < 0·05).

IELs kill colon cancer through FasL and TNF-α

HT-29 cells have been shown to be resistant to Fas-mediated lysis by T cells.19 To evaluate this with IELs, cytotoxicity was measured against cell lines particularly susceptible to perforin-, TNF-α-, or FasL-induced lysis (Fig. 2). When incubated for 4-hr or 18-hr with radiolabelled P815 cells (coated with anti-CD3), IELs displayed no perforin-directed lysis, although they gained this function with interleukin-15 (IL-15) stimulation.24 When contacting the TNF-α-susceptible WEHI cells, IELs killed a moderate number of these targets through TNF receptor type I. When exposed to the FasL-susceptible Jurkat cells, IELs displayed marked cytotoxicity. Thus the fresh IELs were capable of TNF-α and FasL-mediated killing but not perforin-induced redirected lysis. The degree of killing was maximal by 4 hr, indicating that a prolonged effector–target cell incubation was not required. This contrasted with the experiments where colon cancer cells were the targets, in which prolonged effector–target cell contact increased cytotoxicity.

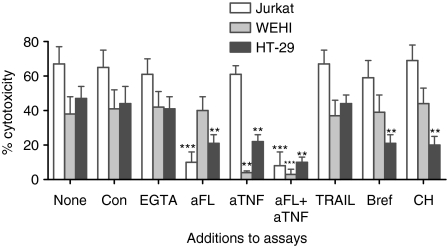

The mechanisms by which IELs spontaneously lyse HT-29 cells were investigated, again looking at perforin-, TNF-α-, and FasL-mediated lysis (Fig. 7). To identify perforin-mediated events, concanamycin was added to the assay because it accelerates degradation of perforin by increasing the pH of the lytic granules.25 It had little effect on SC by IELs against HT-29 cells. Since degranulation requires calcium, a chelating agent, EGTA with MgCl2, was added to the assay. During a 4-hr incubation it did not affect cytotoxicity. An 18-hr assay could not be performed because the EGTA caused excessive release of radiolabel. Serine esterase release was then measured (Table 2). Although IL-15-activated IELs released serine esterases, fresh IELs, whether cultured alone or with HT-29 cells, did not. This indicated little perforin-mediated lysis, consistent with the lack of redirected lysis using P815 cells. Next, the role of TNF-α was determined by recording the drop in cytotoxicity with addition of a TNF-neutralizing antibody to the assay. Cytotoxic activity against HT-29 cells was partially reduced, indicating some TNF-α-mediated killing. Finally, the effects of anti-FasL were determined. A partial reduction in lysis occurred. The combination of anti-TNF-α and anti-FasL additively reduced cytotoxicity by about 90%. The lack of effect by anti-TRAIL served as a negative control. Taken together, this shows that IELs kill HT-29 cells utilizing TNF-α and FasL, but not perforin. Jurkat cells, in contrast, were only affected by anti-FasL, while WEHI cells were only affected by anti-TNF-α.

Figure 7.

IELs were cultured with radiolabelled Jurkat, WEHI, or HT-29 cells (the last pretreated with IFN-γ) for 18 hr (or 4 hr with EGTA). Antibodies (designated as ‘a’) or metabolic inhibitors were added: ‘con’ for concanavalin A, ‘bref’ for brefeldin A, and ‘CH’ for cycloheximide. The percentage cytotoxicity is depicted. Values significantly different from ‘none’, as determined by anova with the Tukey test, were marked as: **P < 0·01 and ***P < 0·001.

Table 2.

Serine esterase release by IELs

| Cell stimulation | Serine esterase release (optical density) |

|---|---|

| No cells | 0·212 ± 0·05 |

| IEL alone | 0·221 ± 0·04 |

| IEL + HT-29 | 0·234 ± 0·06 |

| IEL + IL-15 | 0·410 ± 1·1 |

IELs were cultured in medium alone, with HT-29 cells, or with IL-15 (10 ng/ml) for 18 hr. The amount of serine esterase released (measured in optical density) was measured.

The prolonged assay required for optimal cytotoxicity of the colon cancer cells, but not Jurkat cells, suggests that metabolic processing is required for the former. To evaluate this, IELs were pretreated with cycloheximide or brefeldin A before addition to an18-hr cytotoxicity assay with HT-29, Jurkat, or WEHI cells (Fig. 7). Cytotoxicity declined with either agent when IELs were directed against HT-29 cells. Lysis of Jurkat and WEHI cells, however, was unchanged.

To determine whether secretion of FasL, TNF-α, and IFN-γ was sensitive to cycloheximide or brefeldin A, IELs were cultured for 18 hr in the presence or absence of these inhibitors. Spontaneous FasL release dropped from 280 ± 53 pg/ml to 98 ± 10 pg/ml with cycloheximide and to 82 ± 17 pg/ml with brefeldin A. The low spontaneous TNF-α levels (averaging 15 ± 5 pg/ml) dropped to 3 ± 3 pg/ml and 4 ± 2 pg/ml, respectively. IFN-γ production, too, declined from 140 ± 15 pg/ml to 66 ± 8% and 56 ± 10%, respectively. The long duration of effector-to-target cell coupling, then, may permit the externalization of FasL, TNF-α and IFN-γ, which attack HT-29 cells with low Fas and TNFR1 expression (Table 1). The up-regulation of FasL is not necessary to lyse Jurkat or WEHI cells with their high Fas and TNFR1 expression, respectively.

Optimal cytotoxicity requires FasL, TNF-α, and IFN-γ

The IELs killed 23 ± 8% of untreated HT29 cells and 58 ± 7% of IFN-γ-treated target cells, indicating that IFN-γ increased susceptibility to lysis (Fig. 2). If untreated HT-29 cells were cultured with IELs in the presence of anti-IFN-γ, lysis declined substantially (cytotoxicity of 32 ± 10% without and 15 ± 5% with anti-IFN-γ, P < 0·01), indicating that the IELs could provide IFN-γ, which increased target cell destruction.

The effects of IFN-γ on the surface markers of colon cancer cells were evaluated by immunofluorescence because treatment with IFN-γ markedly up-regulated cytotoxicity (Table 1). The dramatic increase in MHC class II (HLA-DR) expression showed that IFN-γ effectively altered the HT-29 cells. IFN-γ treatment also increased low expression of Fas and TNFR1, but had minimal effects on E-cadherin, ULBP1, ULBP2, ULBP3 and MICA.

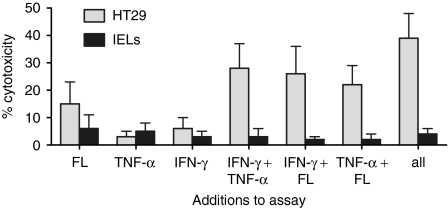

The killing of HT-29 cells was mediated by an additive effect of FasL and TNF-α. This could be because the separate populations were susceptible to either mediator or because both agents were required to kill the target cells. To investigate these possibilities, radiolabelled HT-29 cells were cultured with combinations of soluble FasL, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (all at 10 ng/ml), and the resulting 51Cr-release was measured after 18 hr (Fig. 8). Each mediator alone induced little killing, but combinations of two were cytotoxic. Importantly, soluble FasL augmented killing when combined with either TNF-α or IFN-γ, whereas it has been reported to block killing in other systems.26

Figure 8.

Radiolabelled HT29 cells (not treated with IFN-γ) and IELs were cultured with combinations of soluble FasL, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (all at 10 ng/ml) for 18 hr, and the percentage cytotoxicity was measured.

Colonic adenocarcinoma cells have been shown to express FasL that is able to attack lymphocytes.19 To evaluate this, radiolabelled IELs were cultured with HT-29, SW480, or LOVO cells (at a 5 : 1 ratio) for 18 hr, and release of radiolabel was recorded. There was no release, indicating no tumour counterattack. Furthermore, culturing IELs with any of the soluble mediators—FasL, TNF-α, or IFN-γ—did not induce lysis, even when combined (Fig. 8). This was the result of undetectable expression of Fas or TNFR1 on IELs by flow cytometry (not shown). Cytotoxicity, therefore, was unidirectional; there was no tumour counterattack in this system.

Discussion

The IELs, located next to ECs, are well situated to detect and kill those ECs that become dysplastic or malignant. Many CD8+ TILs may be derived from IELs because they share phenotypic and functional characteristics.1,2,4 This study analyses the battle between IELs and colon cancer in achieving dominance (Fig. 1). The binding of MIC/ULBP on the colon cancer to NKG2D on IELs promotes the generation of FasL and participates in the FasL-mediated cytotoxicity. The TNF-α produced independently of the NKG2D–MIC/ULBP interaction works together with FasL to destroy tumour. Interferon-γ, whose production is also NKG2D-independent, further optimizes cytotoxicity by up-regulating Fas- and TNFR-1 expression on the tumour cells. The immunological synapse is strengthened by the binding of CD103 on IELs to E-cadherin on colon cancer.21 The TCR–MHC class I interaction, in contrast, has no role in SC, indicating that this is not an antigen-driven event. The cytotoxicity is unidirectional with IELs killing HT-29 cells without a tumour counterattack.

As shown here, HT-29 cells are not susceptible to soluble FasL alone, and have been reported to be resistant to Fas-mediated cytotoxicity.19 Therefore, other mediators may be involved. One possibility is perforin. However, fresh IELs had no spontaneous perforin-mediated cytotoxicity. They were incapable of lysing anti-CD3-coated P815 cells or K-562 cells20 and neither concanamycin nor EGTA had an effect on SC activity against HT-29 cells. Furthermore, no serine esterase release was detected. The lack of granule-mediated lysis in the presence of FasL-induced killing suggests that FasL is not stored in lytic granules, as suggested by some but not all studies.27,28 Interleukin-2-activated and IL-15-activated IELs, in contrast to fresh cells, have perforin-mediated redirected lysis and lymphokine-activated killing activity against EC tumour targets.29 Resistance of K-562 to spontaneous lysis indicates that most of the cytolytic activity is not the result of the small NK population in the IELs.20 This was further proven by the stable IEL killing of HT-29 cells despite the removal of the CD16+ and CD56+ subset.20 Human memory CD8+ T cells and CD8+ TILs both lack perforin-mediated lysis.3,4 In the case of TILs, this is thought to be the result of negative influences within the tumour microenvironment that can be reversed by IL-2. Another view of the data is that the lack of perforin-mediated cytotoxicity by TILs is a property of most antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells.

Another mediator that proved to be important was TNF-α. Systemic cytotoxicity occurred by the combined actions of FasL and TNF-α against the HT-29 cells or by their functioning separately to destroy the Jurkat and WEHI cells, respectively. FasL-induced cytotoxicity of the HT-29 cells differed from that of the Jurkat cells. First, the extended coculture of effector and target cell from 4 hr to 18 hr increased lysis of HT-29 cells, but not of Jurkat cells. Second, brefeldin A or cycloheximide treatment of IELs reduced lysis of HT-29 cells but not of Jurkat cells. Brefeldin A inhibits the transport of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi, and from there to the surface. It reduces the externalization and secretion of FasL, TNF-α and IFN-γ. Its effects on membrane FasL and TNF-α were difficult to quantify because of the low detection by flow cytometric analysis. One interpretation of these data is that the low Fas expression on HT-29 cells makes these cells relatively resistant to lysis. However, extending the coculture of IELs with HT-29 cells permits the externalization of FasL and TNF-α, which bind more sites on the target cell. This is not necessary when IELs are confronted with the Jurkat or WEHI cells, which express high levels of Fas and TNFR1, respectively. It is possible that brefeldin A is inhibiting the expression of other markers, such as NKG2C.30 NKG2C, however, is unlikely to be involved because CD94– IELs carry out SC activity.

The battle of IELs against EC tumours involves, not only FasL and TNF-α, but also IFN-γ. Interferon-γ is produced by tumour-stimulation of lymphocytes13 and, as shown here, is an important up-regulator of SC activity. This was illustrated by the increased susceptibility of HT-29 cells to lysis if they were pretreated with IFN-γ and by the decline in SC activity of untreated target cells with addition of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ antibody to the assay. Interferon-γ up-regulates Fas and TNFR1 expression, which is in agreement with previous findings,13 but does not affect MIC or ULBP.

The NKG2D pathway is involved in SC activity when its ligands are present on the EC tumour cells, even at very low levels. While there was a partial decrease in SC activity when one to three of the four ligands were blocked, there was near-elimination when all of them were disarmed. This indicates that one ligand alone can involve the NKG2D pathway. Importantly, IELs killed MIC-transfectants through FasL but not TNF-α; MIC induced the generation of FasL, but not TNF-α or IFN-γ. This establishes a novel role of MIC in inducing FasL-mediated cytotoxicity and is counter to the finding that FasL killing is independent of NKG2D in NK cells.27,31

HT-29 cells were killed by the combined action of FasL, TNF-α and IFN-γ rather than separate populations being susceptible to each mediator. A previous study showed that the combination of IFN-γ with either activating Fas antibody or TNF-α resulted in the death of HT-29 cells.32 The important difference is the demonstration here that soluble FasL can contribute to the cytotoxicity. In other systems, release of FasL may block the Fas pathway by binding Fas without inducing the trimerization required for initiation of apoptosis.26

Finally, IELs are not susceptible to tumour counterattack like Jurkat cells.19 Nor are they killed by soluble FasL, TNF-α and IFN-γ, indicating that they clearly prevail in the effector–tumour interaction. TILs, too, are not killed by tumour cells.33 In fact, tumours promote their own FasL-mediated death by stimulating NKG2D on the IELs. Although not yet described, there may be colon cancers that lack all NKG2D ligands and can thereby evade death, perhaps explaining those Fas-resistant subtypes with metastatic behaviour.34

The series of events leading to SC activity by human IELs against colon cancer is novel. While other studies have shown that IELs possess FasL-induced lysis of Jurkat cells,35,36 there are no reports of TNF-α-mediated cytotoxicity, nor of the combined action of FasL and TNF-α against colon cancer. This mechanism of cytotoxicity by human IELs has not been described with human NK or CD8+ T cells, or with murine IELs. It may, however, be a property of TILs bearing the same phenotype as IELs.

References

- 1.Jarry A, Cerf-Bensussan N, Brousse N, Guy-Grand D, Muzeau F, Potet F. Same peculiar subset of HML1+ lymphocytes present within normal intestinal epithelium of gastrointestinal carcinomas. Gut. 1988;29:1632–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.12.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostenstad B, Lea T, Schlichting E, Harboe M. Human colorectal tumour infiltrating lymphocytes express activation markers and the CD45RO molecule, showing a primed population of lymphocytes in the tumour area. Gut. 1994;35:382–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meng Y, Harlin H, O'Keefe JP, Gajewski TF. Induction of cytotoxic granules in human memory CD8+ T cell subsets requires cell cycle progression. J Immunol. 2006;177:1981–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radoja S, Saio M, Schaer D, Koneru M, Vukmanovic S, Frey AB. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T cells are deficient in perforin-mediated cytolytic activity due to defective microtubule-organizing center mobilization and lytic granule exocytosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:5042–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DePaola F, Ridolfi R, Riccobon A, et al. Restored T cell activation mechanisms in human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from melanomas and colorectal carcinomas after exposure to interleukin 2. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:320–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naito Y, Saito K, Shiiba K, Ohuchiu A, Saigenji K, Nagura H, Ohtani H. CD8+ T cells infiltrated within cancer cell nests as a prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3491–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales S, Groh V, Spies T. Immunobiology of human NKG2D and its ligands. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol. 2006;298:121–38. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groh V, Bahram S, Bauer S, Herman A, Beauchamp M, Spies T. Cell stress-regulated human major histocompatibility complex class I gene expressed in gastrointestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perera L, Shao L, Patel A, et al. Expression of non-classical class I molecules by intestinal epithelial cells. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2007;13:298–307. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raulet DH. Roles of the NKG2D immunoreceptor and its ligands. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:781–90. doi: 10.1038/nri1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pende D, Rivera P, Marcenaro S, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain A and UL16-binding protein expression on tumor cell lines of different histotypes: analysis of tumor susceptibility to NKG2D-dependent natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maccalli C, Pende D, Castelli C, Mingari MC, Robbins PF, Parmiani G. NKG2D engagement of colorectal cancer-specific T cells strengthens TCR-mediated antigen stimulation and elicits TCR independent anti-tumor activity. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2033–43. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullbacher A, Lobigs M, Hla RT, Trans T, Stehle T, Simon MM. Antigen-dependent release of IFN-γ by cytotoxic T cells up-regulates Fas on target cells and facilitates exocytosis-independent specific target cell lysis. J Immunol. 2002;168:145–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergmann-Leitner ES, Abrams SI. Differential role of Fas/Fas ligand interactions in cytolysis of primary and metastatic colon carcinoma cell lines by human antigen-specific CD8+ CTL. J Immunol. 2000;164:4941–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connell J, Bennett MW, Nally K, O'Sullivan GC, Collins JK, Shanahan F. Interferon-γ sensitizes colonic epithelial cell lines to physiological and therapeutic inducers of colonocyte apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2000;185:331–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200012)185:3<331::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groh V, Wu J, Yee C, Spies T. Tumour-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 2002;419:734–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldhauer I, Steinle A. Proteolytic release of soluble UL16-binding protein 2 from tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2520–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J-C, Lee K-M, Kim D-W, Heo DS. Elevated TGF-β1 secretion and down-modulation of NKG2D underlies impaired NK cytotoxicity in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2004;172:7335–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connell J, O'Sullivan GC, Collins JK, Shanahan F. The Fas counterattack: Fas-mediated T cell killing by colon cancer cells expressing Fas ligand. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1075–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taunk J, Roberts AI, Ebert EC. Spontaneous cytotoxicity of human intraepithelial lymphocytes against epithelial cell tumors. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts AI, O'Connell SM, Ebert EC. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes bind to colon cancer cells by HML-1 and CD11a. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1608–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shires J, Theodoridis E, Hayday AC. Biological insights into TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes provided by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) Immunity. 2001;15:419–34. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinle A, Li P, Morris DL, Groh V, Lanier LL, Strong RK, Spies T. Interactions of human NKG2D with its ligands MICA, MICB, and homologs of the mouse RAE-1 protein family. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:279–87. doi: 10.1007/s002510100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts AI, Lee L, Schwarz E, Groh V, Spies T, Ebert EC, Jabri B. NKG2D receptors induced by IL-15 costimulate CD28-negative effector CTL in the tissue microenvironment. J Immunol. 2001;167:5527–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kataoka T, Shinohara H, Takayama H, Takaku K, Kondo S, Yonehara S, Nagai K. Concanamycin A, a powerful tool for characterization and estimation of contribution of perforin- and Fas-based lytic pathways in cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1996;156:3678–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suda T, Hashimoto H, Tanaka M, Ochi T, Nagata S. Membrane Fas ligand kills human peripheral blood T lymphocytes, and soluble Fas ligand blocks the killing. J Exp Med. 1997;186:2045–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdool K, Cretney E, Brooks AD, et al. NK cells use NKG2D to recognize a mouse renal cancer (Renca), yet require intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on the tumor cells for optimal perforin-dependent effector function. J Immunol. 2006;177:2575–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bossi G, Griffiths GM. Degranulation plays an essential part in regulating cell surface expression of Fas ligand in T cells and natural killer cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:90–6. doi: 10.1038/4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebert EC. IL-15 converts human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes to CD94+ producers of IFN-γ and IL-10, the latter promoting Fas ligand-mediated cytotoxicity. Immunology. 2005;115:118–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borrego F, Kabat J, Sanni TB, et al. NK cell CD94/NKG2A inhibitory receptors are internalized and recycle independently of inhibitory signaling processes. J Immunol. 2002;169:6102–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayakawa Y, Kelly JM, Westwood JA, Darcy PK, Diefenbach A, Raulet D, Smyth MJ. Cutting edge: tumor rejection mediated by NKG2D receptor–ligand interaction is dependent upon perforin. J Immunol. 2002;169:5377–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abreu-Martin MT, Vidrich A, Lynch DH, Targan SR. Divergent induction of apoptosis and IL-8 secretion in HT-29 cells in response to TNFα and ligation of Fas antigen. J Immunol. 1995;155:4147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaks TZ, Chappell DB, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Fas-mediated suicide of tumor-reactive T cells following activation by specific tumor: selective rescue by caspase inhibition. J Immunol. 1999;162:3273–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu K, McDuffie E, Abrams SI. Exposure of human primary colon carcinoma cells to anti-Fas interactions influences the emergence of pre-existing Fas-resistant metastatic subpopulations. J Immunol. 2003;171:4164–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morimoto Y, Hizuta A, Ding EX, et al. Functional expression of Fas and Fas ligand on human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:84–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gelfanov V, Gelfanova V, Lai YG, Liao NS. Activated αβ-CD8+, but not αα-CD8+, TCRαβ+ murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes can mediate perforin-based cytotoxicity, whereas both subsets are active in Fas-based cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1996;156:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]