Abstract

Satellite glial cells (SGCs) tightly envelop the perikarya of primary sensory neurons in peripheral ganglion and are identified by their morphology and the presence of proteins not found in ganglion neurons. These SGC-unique proteins include the inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1, the connexin-43 (Cx43) subunit of gap junctions, the purinergic receptor P2Y4 and soluble guanylate cyclase. We also present evidence that the small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel SK3 is present only in SGCs and that SGCs divide following nerve injury. All the above proteins are involved, either directly or indirectly, in potassium ion (K+) buffering and, thus, can influence the level of neuronal excitability, which, in turn, has been associated with neuropathic pain conditions. We used in vivo RNA interference to reduce the expression of Cx43 (present only in SGCs) in the rat trigeminal ganglion and show that this results in the development of spontaneous pain behavior. The pain behavior is present only when Cx43 is reduced and returns to normal when Cx43 concentrations are restored. This finding shows that perturbation of a single SGC-specific protein is sufficient to induce pain responses and demonstrates the importance of PNS glial cell activity in the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: RNAi, Kir4.1, SK3, P2Y4, connexin-43

INTRODUCTION

The maintenance of a low extracellular K+ concentration is crucial for controlling the neuronal resting membrane potential and neuronal excitability. In sensory ganglia, increased neuronal excitability has been associated with the occurrence of altered sensation, including the development of neuropathic pain (Amir and Devor, 2003a; Amir and Devor, 2003b). The primary means of limiting extracellular levels of K+ in sensory ganglia occurs through a process that is commonly referred to as ‘spatial buffering’ or ‘siphoning’, and is mediated by satellite glial cells (SGCs). Accordingly, SGCs have a highly negative resting membrane potential and marked K+ permeability (Hosli et al., 1978).

In the CNS, glial buffering of extracellular K+ is carried out by astrocytes and consists of uptake by inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channels and dissipation through other channels such as Ca2+-activated K+ channels, and through gap junctions (Konishi, 1996; Huang et al., 2005). Although it is established that Kir current and Kir4.1 expression occur in SGCs (Hibino et al., 1999), it is unclear if any Ca2+-activated K+ channels are also found on these cells. To address this question we focused on the small conductance SK3 channel because it was recently found to be strongly expressed in astrocytes (Armstrong et al., 2005).

It is also well known that gap junctions join adjacent glial cells in the CNS and SGCs in ganglia and permit the passage of K+ and other small molecules between adjacent cells (Konishi, 1996; De Pina-Benabou et al., 2001; Weick et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005). After injury, the number of gap junctions that connect SGCs increases (Hanani et al., 2002; Pannese et al., 2003) in a probable adjustment to the greater release of K+ associated with intense neuronal activity. A major structural component of gap junctions are connexins and the subunit connexin-43 (Cx43) is expressed preferentially by glial cells in the CNS (Nagy et al., 2004; Theis et al., 2005). The composition of gap junctions between SGCs has not been determined and it is not known if Cx43 occurs in SGCs, or what would be the behavioral effect of decreasing its expression in the trigeminal ganglion.

Injury to a peripheral nerve does not directly impact SGC integrity. However changes in injured neurons can influence the ability of the surrounding SGCs to regulate K+ via neuromodulators such as adenosine triphospate (ATP) and nitric oxide (NO) (Weick et al., 2003; Filippov et al., 2004; Schubert et al., 2004; Benfenati et al., 2006). With respect to ATP signaling, the identity of the purinergic receptors expressed by SGCs is not clear. In a recent study, Kobayashi and colleagues (Kobayashi et al., 2006) found that SGCs express mRNAs encoding P2Y2 and P2Y4 but not the P2Y4 protein. In contrast, Weick and colleagues (Weick et al., 2003) reported that the P2Y4 receptor is present in SGCs whereas Ruan and colleagues (Ruan and Burnstock, 2003) found it to be expressed by primary sensory neurons only. The action of NO is proposed to be on a glial-specific form of guanylyl cyclase called alpha1-guanylyl cyclase (Kummer et al., 1996), which catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP).

OBJECTIVE

We wish to show, using new data and a review of previously published evidence, that SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion express a unique complement of proteins that are critical to maintaining homeostasis. Many of these proteins are directly (Kir4.1, Cx43) or indirectly (P2Y4 and guanylyl cyclase) involved in the trafficking of K+ ions. We also show that, contrary to previous studies, the SK3 channel is also found only in SGCs and not in neurons. Finally we wish to demonstrate that RNAi is a powerful method for reducing the expression of single proteins in vivo and such manipulation is robust enough to result in behavioral changes.

METHODS

Animals, surgeries and dsRNA

Animals

Adult, male, Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) weighing 270–330 g were housed on a 12 h light–dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. Procedures for the maintenance and use of the experimental animals conformed to the regulations of UCSF Committee on Animal Research and were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the NIH regulations on animal use and care (Publication 85-23, Revised 1996).

Chronic constriction injury of the infra-orbital nerve

A 2-cm skin incision was made along the upper edge of the orbit to expose the skull and nasal bone. Gentle retraction of the orbital content exposed ~5 mm of the infra-orbital nerve (ION) and two ligatures (5.0 chromic gut) were loosely tied around the exposed nerve. The incision was closed using 6.0 silk.

Cannula implant for injection in the maxillary division of the trigeminal ganglion

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine–xylazine (90 mg kg−1, www.abbott.com; 10 mg kg−1, Xyla-Ject) and positioned in a stereotaxic apparatus. The skull was exposed and a burr hole drilled above the location of the maxillary division of the left trigeminal ganglion (6.5 mm anterior to intra-aural zero and 2.3 mm from the midline) (Schneider et al., 1981). A stainless steel cannula guide pedestal (www.plastics1.com) was fixed to the skull over the hole using three stainless steel screws (www.smallparts.com) and dental acrylic cement.

Synthesis of dsRNA and preparation for injection

cDNA of the gene of interest was produced by reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA followed by a 30-cycle PCR using gene-specific primers and cloned into pTOPO vector (www.invitrogen.com). The specific forward and reverse primer sequences for Cx43 corresponded to nucleotides 307–324 and 725–742, respectively (GenBank accession number NM–012567). Rat β-globin sequences were used as nonspecific dsRNA control as described previously (Bhargava et al., 2004). Sense and antisense RNA were synthesized from cDNA inserts by using MegaScript RNA kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Before injection into the trigeminal ganglion, 15 μg of control of Cx43 dsRNAs were mixed with 1 μl of lipofectamine-2000 as a lipid carrier of dsRNA (www.invitrogen.com) in a final volume of 5 μl and allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min. Before injection, the red fluorescent marker DiI (Molecular Probes) was added to the mixture at a final concentration of 10 μM.

Injection into the trigeminal ganglion

Injection was carried out with the rat under isoflurane anesthesia. A 33-gauge, beveled, stainless steel cannula (www.plastics1.com) was inserted through the guide cannula (positioned as described above) to 9.5 mm below the cortical surface. The injection cannula was connected to a 25 μl syringe attached to a microinjection pump set to deliver 5 μl at a rate of 2 μl min−1. A final volume of 5 μl containing dsRNA/lipid and dye was delivered into the ganglion.

Behavioral testing and statistical analysis

Spontaneous eye closure

The animals were placed individually in a Plexiglas® testing chamber (10 cm × 15 cm × 19 cm) with mirrors on two walls so the rats could be observed whichever direction they faced. The number of unilateral left-eye and right-eye closures was recorded for three periods of 2 min at 5-min intervals. The testing sessions were videotaped for post-test analysis. The results are presented as the number of events per min.

Behavioral testing was carried out in rats randomly assigned to one of four experimental groups; globin dsRNA (n = 6), Cx43 dsRNA (n = 6), sham-CCI (n = 3) and CCI (n = 4). Baseline values were recorded in naïve rats before surgery. In the RNAi experiment, rats were tested again (after implantation of guide cannula (1 day before dsRNA injection) and 1, 3, 5 and 7 days after the injection of dsRNA. In the nerve-injury experiment, eye closures were recorded only once, 7 days after either sham-operation or CCI.

Statistics

All results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All the data recorded were computed and analyzed using SigmaStat software (www.systat.com). In the RNAi experiment, differences between the two dsRNA groups (globin and Cx43) and changes over time were analyzed for ipsilateral and contralateral closure with a mixed repeated measure-analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons between groups. Significant changes post-dsRNA injection were established by comparison with baseline values (naïve animals) using Student's t-test for paired data. In each group, differences between ipsilateral and contralateral sides to the injection were tested over time with a two-way RM-ANOVA, followed by multiple comparisons between both sides using the paired t-test. The magnitude of the effect in dsRNA-injected rats was determined for day 3 (day of maximum effect) by comparison with a 7-day CCI of the ION (and sham-operation). The differences of dsRNA-day3 or injury-day7 with their respective baseline values were calculated and a one-way ANOVA was performed to assess differences between the four groups. The Bonferroni post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons between groups.

Tissue processing

Histology

Rats were deeply anesthetized with 100 mg kg−1 of pentobarbital (i.p.). For light microscopy, animals were perfused transcardially with 10% formalin. The trigeminal ganglia were removed and post-fixed in the same fixative for 30 min, and then cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in PBS (pH 7.4) for 48 hours. The left and right trigeminal ganglia from each animal were embedded together and cut longitudinally at 10 μm on a cryostat. For quantification we used a computer driven unbiased counting system (StereoInvestigator, MicroBrightField Inc.) and analyzed 15 sections from each animal.

For electron microscopy (EM) rats were perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde and post-fixed for 5 hours. Fifty μm vibratome sections were osmicated, dehydrated and embedded in Epon. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate (Ohara and Lieberman, 1985).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was carried out on sections from all the rats used for the behavioral testing (19 rats) using standard protocols (Vit et al., 2006a; Vit et al., 2006b) and in some cases chromogen amplification (Goff et al., 1998). Omitting the primary antiserum or pre-absorbing the antibody against the peptide controlled for non-specific labeling. The following antibodies were used, with dilutions for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blot (WB) as indicated: SK3 (IHC, 1:5,000), Kir4.1 (IHC, 1:5,000) and P2Y4 (IHC, 1:5,000) (Alomone Laboratories); glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; IHC, 1:100,000), neuronal-nuclear protein (NeuN; IHC, 1:10,000), GLAST (IHC, 1:8,000), cGMP (IHC, 1:2,000) and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; IHC, 1:1,000) (Chemicon) Cx43 (IHC, 1:1,000 and WB, 1:300) (Zymed Laboratories) and P2X3 (IHC, 1:4,000) (Neuromics).

Histochemistry

Activity of neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) was determined by NADPH diaphorase histochemistry. Trigeminal ganglion cryostat sections were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then incubated in pre-heated (37°C) reaction buffer consisting of 1 mg ml−1 reduced β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (β-NADP), 0.1 mg ml−1NitroBlueTetrazolium, 1% Triton X-100 (all reagents from www.sigmaaldrich.com) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 8.0). The reaction was carried out at 37°C for 1 hour. At the end of the incubation sections were air-dried, dipped in xylene and coverslipped with DEPEX.

Histological quantification

Densitometry was carried out on 10 μm cryostat sections in a treatment-blinded manner using a procedure described previously (Goff et al., 1998). Six, non-overlapping images were taken at 60 × magnification from the region of the ION from each of five sections separated by 10 sections (i.e. a total of 30 sample sites). The images are then set to a uniform threshold value and all the black pixels counted using Scion Image software (Scion Corp.). The results are expressed as pixels per 1,000 square micra. The values of all the sample sites are averaged to give the average pixel density for each ganglia. We used StereoInvestigator (MicroBrightField Inc.) for unbiased cell counting. Cells are counted on non-overlapping sampling sites (the number of sites determined by the software based on preliminary population estimates) from five sections with each section separated by 10 sections. The software calculates the total number of cells per unit area for each ganglion analyzed. For both densiometric and cell counting, the same sampling procedure and area sampled is used for experimental and control ganglia. The data is presented as the number of pixels or cells per unit area and the experimental groups were compared using a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Protein extraction and WB

Unfixed trigeminal ganglia were removed from rats euthanized with 100 mg kg−1 pentobarbital (i.p.). The tissue was washed in cold PBS and then suspended on ice in protein extraction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.25% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), 1 mM ethylenedia-minetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) supplemented with Complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail (www.roche-applied-science.com). After homogeneization, the sample was centrifuged for 20 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C. The amount of protein in the supernatant was determined by the Bradford method using the Bio-Rad protein assay (www.bio-rad.com). Protein aliquots (20 μg per sample) were resolved by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Equal loading and transfer of proteins was monitored by Ponceau-S staining of the membrane. Blocking was carried out for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.05% Tween-20. Next, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody diluted in the same buffer. Blots were washed three times for 10 min in PBS-0.05% Tween-20, then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)- conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 5% dry milk-PBS-0.05% Tween-20, and finally washed three times for 10 min in PBS-0.05% Tween- 20. Immunoblots were developed using enhanced chemoluminescence (ECL, www.amershambiosciences.com) and exposed to X-OMAT-AR films (www.kodak.com). Films were scanned and band density was quantified using the Scion Image software (www.scioncorp.com). The number of black pixels was counted in a standardized square positioned over each band.

RESULTS

Morphological identification of SGCs

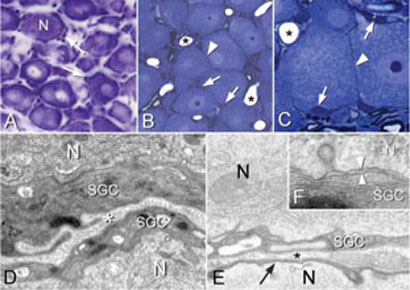

In classical Nissl preparations (Fig. 1A) only the nuclei of SGCs are visible and, although it is clear that these cells surround the neurons, it is difficult to fully appreciate the intimate physical relationship between these two cell types. On thin sections however (Fig. 1B–F), the anatomical relationship between the neuronal cell bodies and SCGs is fully apparent. Several features that are relevant to the buffering activities of SGCs are seen in these images. The classic image (Fig. 1A) gives the appearance that there might be considerable gaps between adjacent neurons whereas in the material prepared for EM it is clear that the neurons are frequently closely apposed (Fig. 1B–F). However, even though some of these neurons might appear to be in contact there are always SGCs in between (Fig. 1D–F). The cytoplasm of the SCGs, which in some cases is very attenuated, prevents contact between neuronal cell bodies. The membranes of the SGCs and neurons are in very close apposition and separated by an extracellular space of ~20 nm (Fig. 1F), a close contact that is necessary for efficient ion exchange.

Figure 1. Morphology of neurons and SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion.

(A) The classical appearance of a Nissl-stained frozen section of a trigeminal ganglion. Neurons do not appear to be tightly packed and the nuclei (arrows) of SGCs are scattered around the neurons. (B,C) Epon semi-thin sections. The primary sensory neurons are packed closely together and in some places appear to be in contact with each other (arrowheads). SGC nuclei (arrows) and blood vessels (*) are also visible. (D,E) Electron micrographs showing neurons (N) surrounded by SGC cytoplasm (SGC). The extracellular space (*) containing collagen fibers is visible. The cytoplasm of the SGCs can be extremely attenuated, as in E (arrow). (F) The N and SGC cell membranes are closely apposed (~20 nm, space between arrowheads), which allows the SGCs to buffer ions that are extruded from the neuron.

Molecular identification of SGCs

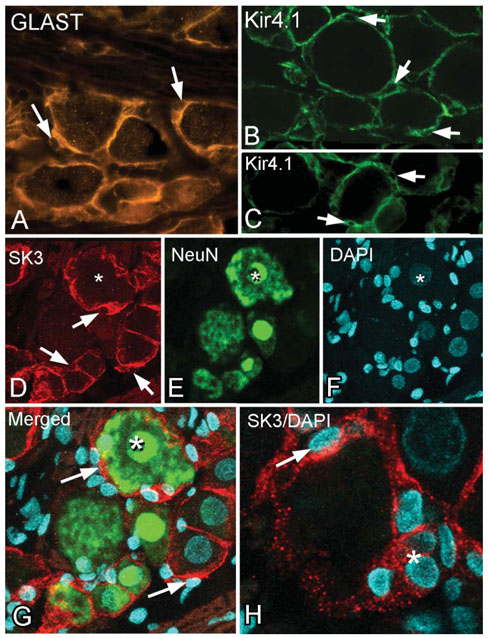

In addition to their structural features, SGCs can be identified by several molecular signatures (see Hanani, 2005). These include the structural protein vimentin, and proteins that are involved in glutamate recycling, namely, glutamine synthase and the glutamate transporter GLAST. Note that the GLAST-positive SGCs surround neurons of all sizes and there is minimal staining of structures that are not in contact with the neurons (Fig. 2A). The unstained nuclei of the SGCs are clearly visible and the SGCs often appear to indent the neuronal cytoplasm in these areas.

Figure 2. Immunocytochemical markers of SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion.

(A) Immunostaining for the glutamate transporter GLAST. The stained cytoplasm and unstained nuclei (arrows) gives a characteristic ‘signet ring’ appearance to the SGCs surrounding the neurons. (B,C) A similar staining pattern for the inwardly rectifying Kir4.1 channel in the trigeminal ganglion (B) and the dorsal root ganglion (C). Immunostaining is confined to the SGCs that surround the neuronal cell bodies, and the characteristic appearance given by the unstained SGC nuclei (arrows) is seen. (D–G) Three, merged 1 mm optical slices from a confocal stack of triple-labeled (SK3, NeuN and DAPI) trigeminal ganglion. * indicates the same neuronal nucleus in each image. (D) The SK3 immunostaining has the same appearance as GLAST and Kir4.1 immunostaining (arrows indicate unstained SGC nuclei). From the merged image (G, shown at higher magnification) there is no overlap between the red SK3 and green NeuN immunostaining, which indicates that SK3 is confined to the SGCs. (H) Another example of DAPI-stained nuclei located in SK3 (red) immunostained SGCs. * marks an en-face view of several SK3-immunopositive SGCs and their DAPI-stained nuclei.

K+ channels

More relevant to the present publication are the markers that are involved in K+ exchange. In the CNS, Kir4.1 is specific to astrocytes and is considered to be the principal mechanism of K+ buffering. SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion also express Kir4.1 (Fig. 2B). This channel has been reported previously in satellite cells of the cochlear ganglion and the trigeminal ganglion but the same authors did not find Kir4.1 immunostaining in the DRG (Hibino et al., 1999). In contrast, we observe Kir4.1 immunostaining of SGCs in the DRG (Fig. 2C) similar to that of the trigeminal ganglia (Fig. 2B). This indicates that Kir4.1 is ubiquitous to glial cells that perform a buffering function both in the CNS and in sensory ganglia in the PNS.

A second K+ channel that is reported to be present in neurons of sensory ganglia is the SK3 channel (Bahia et al., 2005; Mongan et al., 2005). In contrast, we observe that SK3 is confined to SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion. SK3 immunostaining has an identical distribution and appearance to that of GLAST and Kir4.1, including the unstained nuclei and indented neurons (Fig. 2D). Double staining with SK3 and NeuN shows no overlap in label (Fig. 2D,E,G), which confirms that SK3 is confined to SGCs. Further confirmation that SK3 is present in SGCs is provided by nuclear DAPI staining (Fig. 2D,F–H).

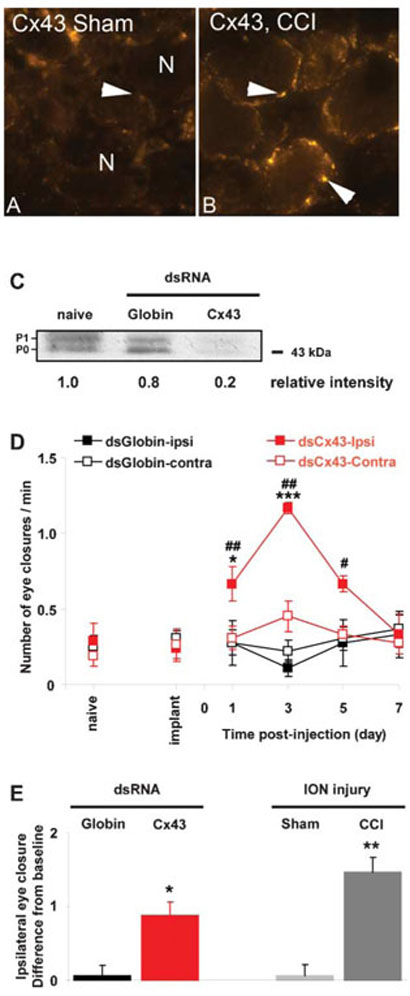

Gap junctions

Once K+ has entered the SGCs it is redistributed to adjacent SCGs through gap junctions (Wallraff et al., 2006). In the CNS, Cx43 is a key component of astrocyte gap junctions (Nagy et al., 1996; Dermietzel et al., 2000). We find that Cx43 is also present in the trigeminal ganglion, as shown by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 3A). Previous EM studies have shown that gap junctions increase in sensory ganglia following peripheral nerve injury. We also find that Cx43 immunostaining increases (Fig. 3A,B) following CCI of the ION (CCI, 95.4 ± 4.1 pixels per 104 μm2 versus sham-CCI, 31.2 ± 3.8 pixels per 104 μm2; P<0.001).

Figure 3. Cx43, immunocytochemistry, western blot and behavior following silencing by RNAi and after injury.

(A,B) Compared to sham surgery (A), Cx43 immunoreactivity increases in the trigeminal ganglion 7 days after CCI of ION (B). Note the punctate labeling pattern restricted to SGCs that encircle sensory neurons. (C) In vivo RNAi suppresses the expression of Cx43 efficiently. Representative immunoblot showing the expression of Cx43 in trigeminal ganglion from naïve and either globin or Cx43 dsRNA-injected rats. The injection of Cx43 dsRNA results in an 80% decrease in Cx43 intensity compared with a non-treated (naïve) trigeminal ganglion. P0 and P1 represent the non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of Cx43, respectively. (D) Spontaneous eye closure increases after injection of Cx43 dsRNA into the trigeminal ganglion. There is a significant interaction between the treatment and the time post-injection only on the ipsilateral side (RMA-NOVA: ipsilateral, F = 11.0, P<0.001 and contralateral, F = 2.0, P = 0.111). The effect of Cx43 dsRNA is seen on the side ipsilateral to the injection only. It consists of an increase in unevoked eye-closure behavior starting at day 1, reaching a maximum on day 3, then declining starting on day 5 to reach baseline on day 7. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 compared to globin dsRNA; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared to baseline (implanted rats). (E) The magnitude of behavior effect following Cx43 dsRNA injection is similar to that observed after nerve injury. The effect of dsRNA on day 3 (maximum) is compared to that of a 7-day CCI of the ION (sham surgery used as control). The data are expressed for each group because the difference in the number of blinks post-treatment with baseline. There is a significant difference between the four groups (one-way ANOVA, F = 12.3, P = 0.001). The difference in the number of blinks with baseline is increased after Cx43 dsRNA injection or CCI and these two treatments are not significantly different (P = 0.231). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to appropriate control (globin dsRNA or sham surgery).

To investigate the role of Cx43 we used in vivo RNAi to temporarily silence Cx43 by injecting Cx43 dsRNA into the maxillary division of the trigeminal ganglion. Western blot (Fig. 3C) confirms the presence of Cx43 in the trigeminal ganglia and shows a reduction in the concentration of Cx43 following Cx43 dsRNA injection whereas injection of globin dsRNA had no effect on Cx43. The decrease in Cx43 was correlated with an increase in spontaneous eye closure (Fig. 3D,E). This increase was significant on the side of the injection starting from day 1 post-dsRNA injection, and reaching a maximum on day. The number of eye closure was back to baseline by day 7 (Fig. 3D). The amplitude of the increase in eye closure was similar to that observed after CCI of the ION (Fig. 3E).

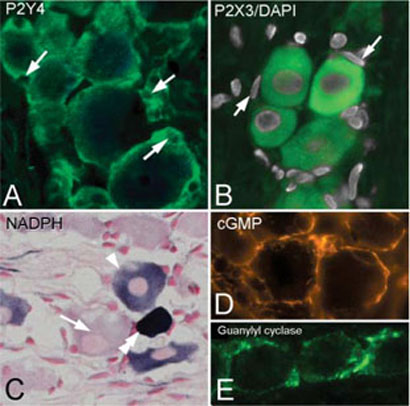

Neurotransmitter modulation of SGCs

Neurons modulate SGCs through at least two neuromediators, ATP and NO. ATP affects both primary sensory neurons and SGCs through metabotropic purinergic receptors such as P2Y4 on SGCs (Weick et al., 2003) and ionotropic purinergic receptors as P2X3 on neurons (Xiang et al., 1998). By immunocytochemistry we show that the P2Y4 receptor is present exclusively in SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion (Fig. 4A) and P2X3 is confined to neurons (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. ATP- and NO-related signaling molecules.

(A) SGCs are immunopositive for the purinergic receptor P2Y4 but neurons are unstained. Arrows indicate SGC nuclei (compare with Fig. 2A–C). (B) Immunostaining for P2X3 receptor (green) labels neurons whereas SGCs are unlabelled and apparent by the absence of staining around DAPI-stained SGC nuclei (arrows). (C) NADPH histochemistry shows that not all ganglion neurons contain nNOS. An unstained neuron (arrow) is next to a medium- (arrowhead) and a densely- (double arrowhead) stained neuron. (D) cGMP immunostaining is present in SGCs but is not seen in neurons. (E) A similar staining pattern is observed for the glial form of guanylyl cyclase (alpha1-subunit).

NO is synthesized by nNOS, which is expressed only in ~10% of sensory ganglia neurons, but this proportion increases after nerve injury (Shi et al., 1998). Using NADPH-diaphorase histochemistry as marker for nNOS, we found a significant increase in small, intensely-reactive NADPH-diaphorase neurons in CCI ganglia (Fig. 4C) compared to sham operated controls (CCI, 24.0 ± 0.5 neurons mm−2 versus sham 2.0 ± 0.1 neurons mm−2; P<0.01, n = 3). The increase in release of NO after injury activates the enzyme guanylyl cyclase in SGCs to catalyze the formation of cGMP (Fig. 4D) (Shi et al., 1998).

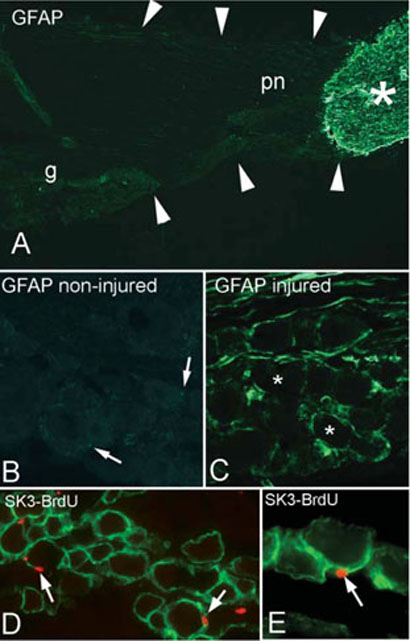

GFAP

GFAP, the archetypal marker for astrocytes, is reported as present at either low levels in the normal SGC or only in some SGCs (Woodham et al., 1989; Ajima et al., 2001; Hanani, 2005; Jimenez-Andrade et al., 2006). In agreement with these reports, we find the expression of GFAP difficult to detect in the normal sensory ganglion (Fig. 5A,B). Fig. 5A illustrates the difference between central and peripheral GFAP labeling, and we find the same pattern of staining using three different GFAP antibodies (data not shown). After nerve injury (Fig. 5C) there is a dramatic increase in GFAP concentration in the trigeminal ganglion (CCI, 6229 ± 1162 pixels 104 μm−2 versus sham-CCI 126 ± 25 pixels 104 μm−2; P<0.001, n = 3). GFAP staining after CCI of the ION has a similar appearance to the other SGC specific markers (compare Fig. 5C with Fig. 2A–C). These results support previous reports of a marked increase in GFAP following injury (Stephenson and Byers, 1995; Takeda et al., 2006).

Figure 5. Changes in molecular markers in the trigeminal ganglion following injury.

(A) GFAP staining of a normal trigeminal nerve shows the dramatic decrease in GFAP staining between the central (*) and the peripheral (pn) portion of the nerve. The arrows outline the limits of the nerve (g, ganglion). (B,C) Photomicrographs taken at the same exposure setting from non-injured (B) and injured ganglia (C). These ganglia are from the same animal, contralateral and ipsilateral to the lesion, and were processed (post-fixation and sectioning) and immunostained together on the same slide. Although GFAP is present in the ganglion on the non-injured side (B, arrows), the normal concentration is low compared with the staining on the injured side (C). * represent the location of unstained neurons. (D,E) Following CCI and systemic injection of BrdU, some SGCs (green, SK3 immunostained) have BrdU-positive nuclei (arrows).

We cannot rule out, however, the possibility that GFAP-positive cells are not the original SGCs showing an increase in expression, but that they are a distinct pool of glial cells that upregulate GFAP in response to nerve injury. A more intriguing possibility is that GFAP-positive cells migrate from a distant site such as the CNS or the PNS/CNS transition zone of the trigeminal central root.

In additional experiments we found that after CCI of the ION, some SGC nuclei are BrdU-positive (Fig. 5D,E), which indicates that they are post-mitotic. This shows that there is a turnover of SGCs in the ganglion, but whether these BrdU-positive cells are SGCs that divided in situ, or whether they are from some other cell type that divided and then migrated to their position around the SGC is under investigation.

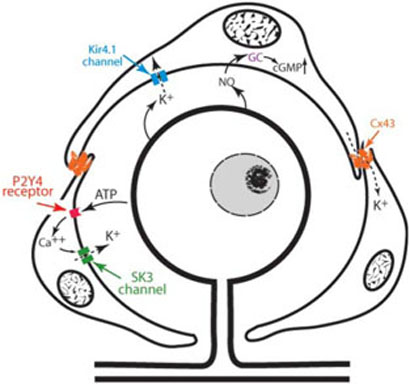

CONCLUSIONS (FIG. 6)

Figure 6. Summary of the elements involved in SGC-associated K+ homeostasis proposed in this review.

All primary sensory neurons are surrounded by SGCs that are connected by Cx43-containing gap junctions. Neuronal activity leads to the release of K+ into the extracellular space and SGCs take it up via the inward rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1 and release K+ via the small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel SK3. Gap junctions permit the redistribution of K+ between SGCs. Neurons modulate the activity of SGCs by releasing ATP, which activates P2Y4 receptors located on the surface of SGCs and leads to the release of intracellular Ca2+. Neurons also modulate the activity of SGCs by releasing NO. NO diffuses in the SCGs where it activates the glial form of the enzyme guanylyl cyclase (GC), which catalyses the formation of the second messenger cGMP. An increase in cGMP and Ca2+ both activate K+ channels.

SGCs in the trigeminal ganglion have the necessary biochemical components and structural relationship with neurons to maintain extracellular K+ at levels conducive to normal neuronal function.

Following nerve injury there is a change in the expression of molecular markers in SGCs, which shows that these cells, in addition to neurons, undergo changes following nerve injury.

Experimental manipulation of the SGC components involved in K+ buffering results in pain-related behavioral changes and underscore the importance of SGCs in normal and pain-related sensory processes.

DISCUSSION

K+ channels

The presence of at least two K+ channels that are located only on SGCs has important functional consequences and support the importance of the role of SGCs in maintaining K+ homeostasis. Our evidence that SK3 is only present on SCGs is significant because two previous reports suggest that this channel is only present on primary sensory neurons (Bahia et al., 2005; Mongan et al., 2005). We argue that close examination of the figures in those studies show that SK3 immunostaining is, in fact, located in SGCs, not in neurons [see Fig. 5B of Bahia and colleagues (Bahia et al., 2005) and Fig. 2C of Mongan and colleagues (Mongan et al., 2005)]. In both photomicrographs the labeled profiles appear peripheral to unlabeled neurons and have the shape of SGCs (notice the similarity to our Fig. 2D). The possibility that this labeling represents neuronal membranes is doubtful given the amount of labeling and because, in many instances, a nucleus is outlined clearly within the labeling (compare to our Fig. 2G where the nuclei and SK3 profiles are closely related). Our interpretation would also explain why Bahia and colleagues (Bahia et al., 2005) found SK3 responses in neurons variable and less common than expected from the immunoassay results.

The impact of our results is that SGC-mediated K+ buffering is probably as crucial following injury as it is for normal neuronal function. A feature of peripheral nerve injury is an increase in neuronal activity that, in turn, places a greater demand on SGCs for the uptake of K+. A deficiency of SGC-mediated K+ buffering will cause an increase in extracellular K+ and neuronal hyperexcitability, a phenomenon that is believed to underlie neuropathic pain. Accordingly, recent studies show that K+-channel openers have potential for the treatment of several CNS disorders that are characterized by neuronal hyperexcitability, such as migraine, epilepsy and neuropathic pain (Neusch et al., 2003; Ocana et al., 2004; Wua and Dworetzky, 2005). Currently, there are cell type-specific modulators of K+ channels available, but these lack selectivity for the different types of K+ channels. For example, apamin and UCL1684 are two potent blockers of Ca2+-activated channels and NS309 is a potent activator of K+ channels, but their effects occur through more than one type of channel (Blank et al., 2004; Strobaek et al., 2004). The finding of glial-specific K+ channels, combined with recent techniques of molecular biology (such as RNAi or gene delivery-associated viral vectors) is promising for the development of powerful gene therapeutics to treat the above mentioned disorders.

Connexin 43

The finding that decreasing Cx43 expression by RNAi results in spontaneous pain behavior (increased eye closure) indicates that a reduction in gap junctions between SGCs leads to greater neuronal excitability, a phenomenon that might worsen nerve injury pain. We use the term ‘eye closure’ rather than ‘blink’ because we do not know if this behavior results from a change in the blink reflex. We interpret the increased spontaneous eye closure as indicative of pain behavior based on our nerve injury experiments. The increase in spontaneous eye closure was ipsilateral to the injured trigeminal nerve, occurred only in injured rats (not after sham-surgery) and was coincident in time with other pain-related behavioral changes, such as von Frey hair stimulation and face grooming behavior (Vos et al., 1994; unpublished observations). Furthermore, the eye closure response to nerve injury was temporarily blocked by an analgesic dose of systemic morphine (unpublished observations). Although it has to be established fully that the eye closure represents a pain response per se, we believe the most likely underlying mechanism is an increased excitability of primary afferent neurons that results in facilitation of the blink reflex (Ayzenberg et al., 2006; Kitagawa et al., 2006), an equivalent of the wincing that is associated with the paroxysms of pain in trigeminal neuralgia. Interestingly, normal blinking originates from the supra-orbital nerve and, to a lesser extent, from the ION, both of which are part of the trigeminal nerve (Esteban, 1999). Furthermore, both blink and nociceptive pathways depend on small diameter primary neurons (Aδ and C fibers) that project to the trigeminal caudalis subnucleus (Zerari-Mailly et al., 2003).

The idea that gap junctions in sensory ganglia have a role in neuropathic pain is new and until now there has only been indirect evidence based on the observation that there is an increase in dye coupling between SGCs following nerve lesions (Hanani et al., 2002; Cherkas et al., 2004). This increase in dye coupling is believed to result from an increase in the number of gap junctions between SGCs (either absolute or simply functional). In the CNS at least six connexins form the subunits of glial gap junctions, and Cx43 might be expressed only in glial cells (Nagy et al., 2004; Theis et al., 2005). Our finding of Cx43 in SGCs is the first demonstration in sensory ganglion, although Hanani in a review (Hanani, 2005) notes that mouse primary sensory ganglion expresses Cx43. If the presence of Cx43 in the SGCs indicates the presence of gap junctions with a similar function to those in the CNS, then these junctions allow the rapid redistribution of K+ and other ions between adjacent SGCs (Huang et al., 2005) to maintain the highly negative intracellular potential. Gap junctions also permit the passage of Ca2+ and are a means by which Ca2+ waves are initiated in adjacent astrocytes. Ca2+ waves also spread via the extracellular diffusion of messenger molecules and in Cx43- knockout mice, Ca2+ waves are still able to propagate by upregulation of the extracellular pathway molecules (Scemes et al., 2000). This indicates that the behavioral changes we see are not because of the loss of Ca2+ movement between SGCs via the gap junctions.

Our finding that decreasing expression of Cx43 results in an increased nociceptive threshold is somewhat at odds with the finding that gap junctions increase after nerve injury (Hanani et al., 2002; Cherkas et al., 2004) where there is spontaneous pain. Our experiments target a single gap-junction component and it is not know exactly what changes occur in gap junctions after injury other than dye-coupling increases. Thus, our experiments and the situation following nerve injury are sufficiently different to suspect that different mechanisms cause the behavioral changes. Our explanation is that the ionic balance in the ganglia is crucial to normal neuronal function and that perturbation of any kind that changes the components regulating ionic homeostasis is sufficient to affect neuronal excitability. Clearly, the role of gap junctions need further investigation. It is tempting to contrast our results with recent studies showing that reduction of gap junctions in the spinal cord of nerve injured rats reduces nociceptive thresholds (Spataro et al., 2004). However, the numerous difference between our experiments, (e.g. central versus peripheral glia, evoked versus spontaneous thresholds and limb versus snout) preclude drawing general conclusions, but do underline the importance of glia in the generation and maintenance of neuropathic pain.

Neuro–glial communication

The relationship between neurons and SGCs is not passive but involves active signaling, at least from the neuron to the SCGs. ATP is a key transmitter in this communication whereas other neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and substance P, which are increased by nerve injury, have no effect on SGCs (Weick et al., 2003). Our results showing that the purinergic receptor P2Y4 is expressed only by SGCs support the finding of Weick (Weick et al., 2003) and provide the basis for ATP-mediated signaling between neurons and SGCs. Thus, in sensory ganglia, ATP might activate SGCs and primary sensory neurons through different receptors, P2Y4 on SGCs and P2X3 on neurons (Xiang et al., 1998). The expression of the P2Y4 receptor by SGCs is somewhat controversial because Ruan and colleagues (Ruan and Burnstock, 2003) found this receptor only expressed by neurons, and Kobayashi and colleagues (Kobayashi et al., 2006) report that P2Y4 is not expressed at all in the sensory ganglion. Currently we are unable to explain this discrepancy.

Activation of the P2Y4 receptor in SGCs might cause an increase in intracellular Ca2+ which, in turn, might activate SK3 (Weick et al., 2003) and Kir channels (Filippov et al., 2004). In this manner, ATP released during nerve injury might trigger changes in extracellular K+ homeostasis and, consequently, changes in neuronal excitability. It is likely, however, that ATP also stimulates the release of growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines by SGCs, as it has been postulated in the CNS (Inoue, 2006).

A second neuron-to-SGC signaling molecule is NO. In agreement with Kummer and colleagues (Kummer et al., 1996), we find that SGCs express alpha1-guanylyl cyclase, the activity of which increases after injury as shown by the production of cGMP. However, because only 10% of the sensory neurons express nNOS, it is unclear how released NO impacts glial cells. Conceivably, the ability of NO to diffuse long distances might stimulate SGCs that are not adjacent to nNOS-containing neurons. NO might activate Kir channels in SGCs (Schubert et al., 2004) lowering the concentration of extracellular K+. Another molecule involved in the NO– cGMP pathway, guanosine, increases the expression of Kir4.1 in astrocytes (Benfenati et al., 2006). This increase in glial Kir4.1 was shown recently to increase the nociceptive threshold in normal animals, and decrease pain behavior after nerve injury (Ma et al., 2006).

Broader implications

We believe SGCs have had received less attention than sensory neurons for several reasons. One is that their small size and close association with sensory neurons makes them difficult to study in vivo and less relevant to study isolated in vitro. Another major reason, in our view, comes from the sometimes stated view that the sensory neuron cell body is itself not important to the transmission of electrical impulses from the periphery to the center. The primary sensory cell body is seen as a metabolic center, without a role in the generation or propagation of nerve impulses. However, not only do afferent spikes invade the cell body of sensory neurons but action potential can be generated by the cell body. After injury, increased excitability of the cell body and the subsequent generation of ectopic action potentials have been proposed to be significant in the generation of neuropathic pain (Amir and Devor, 2003a; Amir and Devor, 2003b). Thus, the ganglion cell body and surrounding SGCs should not be viewed as bystanders to the processes to sensory transmission.

The concept that SGCs have a major role in K+ buffering with subsequent effects on neuronal excitability has broad implications for drug discovery and new therapies. Chanellopathies that are unique to SGCs might underlie several diseases and chronic pain states and, thus, SGCs appear exciting candidates for the development of new targeted therapies. The composition of K+ channels varies between individuals and, together with the idiosyncratic responses of SGCs to specific neurotransmitters, might explain some of the phenotypic differences in pain responses between individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms Cris Cua, Ms Maya Mathur and Ms Prema S. Idumalla for invaluable technical assistance and Ms Neda Shirzadi for editorial assistance. Supported by NS RO1 NS051336-01A1 (L.J.), R21 MH070650 (A.B.) and the Koret Foundation (P.T.O.).

REFERENCES

- Ajima H, Kawano Y, Takagi R, Aita M, Gomi H, Byers MR, et al. The exact expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in trigeminal ganglion and dental pulp. Archives of Histology and Cytology. 2001;64:503–511. doi: 10.1679/aohc.64.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R, Devor M. Electrical excitability of the soma of sensory neurons is required for spike invasion of the soma, but not for through-conduction. Biophysics Journal. 2003a;84:2181–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R, Devor M. Extra spike formation in sensory neurons and the disruption of afferent spike patterning. Biophysics Journal. 2003b;84:2700–2708. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong WE, Rubrum A, Teruyama R, Bond CT, Adelman JP. Immunocytochemical localization of small-conductance, calcium-dependent potassium channels in astrocytes of the rat supraoptic nucleus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;491:175–185. doi: 10.1002/cne.20679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayzenberg I, Obermann M, Nyhuis P, Gastpar M, Limmroth V, Diener HC, et al. Central sensitization of the trigeminal and somatic nociceptive systems in medication overuse headache mainly involves cerebral supraspinal structures. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1106–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahia PK, Suzuki R, Benton DC, Jowett AJ, Chen MX, Trezise DJ, et al. A functional role for small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in sensory pathways including nociceptive processes. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:3489–3498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0597-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfenati V, Caprini M, Nobile M, Rapisarda C, Ferroni S. Guanosine promotes the up-regulation of inward rectifier potassium current mediated by Kir4.1 in cultured rat cortical astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;98:430–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava A, Dallman MF, Pearce D, Choi S. Long double-stranded RNA-mediated RNA interference as a tool to achieve sites-pecific silencing of hypothalamic neuropeptides. Brain Research Protocols. 2004;13:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank T, Nijholt I, Kye MJ, Spiess J. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels as targets of CNS drug development. Current Drug Target CNS Neurological Disorders. 2004;3:161–167. doi: 10.2174/1568007043337472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkas PS, Huang TY, Pannicke T, Tal M, Reichenbach A, Hanani M. The effects of axotomy on neurons and satellite glial cells in mouse trigeminal ganglion. Pain. 2004;110:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pina-Benabou MH, Srinivas M, Spray DC, Scemes E. Calmodulin kinase pathway mediates the K+-induced increase in Gap junctional communication between mouse spinal cord astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:6635–6643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06635.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermietzel R, Gao Y, Scemes E, Vieira D, Urban M, Kremer M, et al. Connexin43 null mice reveal that astrocytes express multiple connexins. Brain Research Brain Research Review. 2000;32:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban A. A neurophysiological approach to brainstem reflexes. Blink reflex. Neurophysiologie Clinique. 1999;29:7–38. doi: 10.1016/S0987-7053(99)80039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov AK, Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Marsh SJ, Simon J, Barnard EA, Brown DA. Activation and inhibition of neuronal G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K(+) channels by P2Y nucleotide receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;66:468–477. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.3.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff JR, Burkey AR, Goff DJ, Jasmin L. Reorganization of the spinal dorsal horn in models of chronic pain: correlation with behaviour. Neuroscience. 1998;82:559–574. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanani M. Satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia: from form to function. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;48:457–476. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanani M, Huang TY, Cherkas PS, Ledda M, Pannese E. Glial cell plasticity in sensory ganglia induced by nerve damage. Neuroscience. 2002;114:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Horio Y, Fujita A, Inanobe A, Doi K, Gotow T, et al. Expression of an inwardly rectifying K(+) channel, Kir4.1, in satellite cells of rat cochlear ganglia. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:C638–C644. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.4.C638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosli L, Andres PF, Hosli E. Neuron-glia interactions: indirect effect of GABA on cultured glial cells. Experimental Brain Research. 1978;33:425–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00235564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TY, Cherkas PS, Rosenthal DW, Hanani M. Dye coupling among satellite glial cells in mammalian dorsal root ganglia. Brain Research. 2005;1036:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K. The function of microglia through purinergic receptors: Neuropathic pain and cytokine release. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;109:210–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Andrade JM, Peters CM, Mejia NA, Ghilardi JR, Kuskowski MA, Mantyh PW. Sensory neurons and their supporting cells located in the trigeminal, thoracic and lumbar ganglia differentially express markers of injury following intravenous administration of paclitaxel in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;405:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa J, Takeda M, Suzuki I, Kadoi J, Tsuboi Y, Honda K, et al. Mechanisms involved in modulation of trigeminal primary afferent activity in rats with peripheral mononeuropathy. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;24:1976–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Fukuoka T, Yamanaka H, Dai Y, Obata K, Tokunaga A, et al. Neurons and glial cells differentially express P2Y receptor mRNAs in the rat dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2006;498:443–454. doi: 10.1002/cne.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T. Developmental and activity-dependent changes in K+ currents in satellite glial cells in mouse superior cervical ganglion. Brain Research. 1996;708:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer W, Behrends S, Schwarzlmuller T, Fischer A, Koesling D. Subunits of soluble guanylyl cyclase in rat and guinea-pig sensory ganglia. Brain Research. 1996;721:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Rosenzweig J, Johns DC, Lamotte RH. Expression of inwardly rectifying potassium channels by an inducible adenoviral vector reduced the neuronal hyperexcitability and hyperalgesia produced by chronic compression of the spinal ganglion. Society for Neuroscience Abstract. 2006;250:255. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongan LC, Hill MJ, Chen MX, Tate SN, Collins SD, Buckby L, et al. The distribution of small and intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in the rat sensory nervous system. Neuroscience. 2005;131:161–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Dudek FE, Rash JE. Update on connexins and gap junctions in neurons and glia in the mammalian nervous system. Brain Research Reviews. 2004;47:191–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Li W, Hertzberg EL, Marotta CA. Elevated connexin43 immunoreactivity at sites of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Research. 1996;717:173–178. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neusch C, Weishaupt JH, Bahr M. Kir channels in the CNS: emerging new roles and implications for neurological diseases. Cell and Tissue Research. 2003;311:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocana M, Cendan CM, Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Baeyens JM. Potassium channels and pain: present realities and future opportunities. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;500:203–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara PT, Lieberman AR. The thalamic reticular nucleus of the adult rat: experimental anatomical studies. Journal of Neurocytology. 1985;14:365–411. doi: 10.1007/BF01217752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannese E, Ledda M, Cherkas PS, Huang TY, Hanani M. Satellite cell reactions to axon injury of sensory ganglion neurons: increase in number of gap junctions and formation of bridges connecting previously separate perineuronal sheaths. Anatomy and Embryology. 2003;206:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s00429-002-0301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan HZ, Burnstock G. Localisation of P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors in dorsal root, nodose and trigeminal ganglia of the rat. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2003;120:415–426. doi: 10.1007/s00418-003-0579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Spray DC. Intercellular communication in spinal cord astrocytes: fine tuning between gap junctions and P2 nucleotide receptors in calcium wave propagation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:1435–1445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JS, Denaro FJ, Olazabal UE, Leard HO. Stereotaxic atlas of the trigeminal ganglion in rat, cat, and monkey. Brain Research Bulletin. 1981;7:93–95. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(81)90103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert R, Krien U, Wulfsen I, Schiemann D, Lehmann G, Ulfig N, et al. Nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside dilates rat small arteries by activation of inward rectifier potassium channels. Hypertension. 2004;43:891–896. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000121882.42731.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi TJ, Holmberg K, Xu ZQ, Steinbusch H, de Vente J, Hokfelt T. Effect of peripheral nerve injury on cGMP and nitric oxide synthase levels in rat dorsal root ganglia: time course and coexistence. Pain. 1998;78:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spataro LE, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Wieseler-Frank J, Schoeniger D, Jekich BM, et al. Spinal gap junctions: potential involvement in pain facilitation. The Journal of Pain. 2004;5:392–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson JL, Byers MR. GFAP immunoreactivity in trigeminal ganglion satellite cells after tooth injury in rats. Experimental Neurology. 1995;131:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobaek D, Teuber L, Jorgensen TD, Ahring PK, Kjaer K, Hansen RS, et al. Activation of human IK and SK Ca2+-activated K+ channels by NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime) Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1665:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M, Tanimoto T, Kadoi J, Nasu M, Takahashi M, Kitagawa J, et al. Enhanced excitability of nociceptive trigeminal ganglion neurons by satellite glial cytokine following peripheral inflammation. Pain (in press) 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis M, Sohl G, Eiberger J, Willecke K. Emerging complexities in identity and function of glial connexins. Trends in Neuroscience. 2005;28:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vit JP, Clauw DJ, Moallem T, Boudah A, Ohara PT, Jasmin L. Analgesia and hyperalgesia from CRF receptor modulation in the central nervous system of Fischer and Lewis rats. Pain. 2006a;121:241–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vit JP, Ohara PT, Tien DA, Fike JR, Eikmeier L, Beitz A, et al. The analgesic effect of low dose focal irradiation in a mouse model of bone cancer is associated with spinal changes in neuromediators of nociception. Pain. 2006b;120:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos BP, Strassman AM, Maciewicz RJ. Behavioral evidence of trigeminal neuropathic pain following chronic constriction injury to the rat's infraorbital nerve. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:2708–2723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02708.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff A, Kohling R, Heinemann U, Theis M, Willecke K, Steinhauser C. The impact of astrocytic gap junctional coupling on potassium buffering in the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:5438–5447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0037-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick M, Cherkas PS, Hartig W, Pannicke T, Uckermann O, Bringmann A, et al. P2 receptors in satellite glial cells in trigeminal ganglia of mice. Neuroscience. 2003;120:969–977. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodham P, Anderson PN, Nadim W, Turmaine M. Satellite cells surrounding axotomised rat dorsal root ganglion cells increase expression of a GFAP-like protein. Neuroscience Letters. 1989;98:8–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wua YJ, Dworetzky SI. Recent developments on KCNQ potassium channel openers. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;12:453–460. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Bo X, Burnstock G. Localization of ATP-gated P2X receptor immunoreactivity in rat sensory and sympathetic ganglia. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;256:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00774-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerari-Mailly F, Dauvergne C, Buisseret P, Buisseret-Delmas C. Localization of trigeminal, spinal, and reticular neurons involved in the rat blink reflex. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2003;467:173–184. doi: 10.1002/cne.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]