Abstract

BACKGROUND

To the authors' knowledge, data characterizing patients' psychosocial experiences after a recurrence diagnosis are limited. This report provides the physical, psychological, and quality-of-life trajectories of patients with recurrent breast cancer. In addition, patients with a well–documented trajectory—patients with their initial diagnosis of breast cancer—were included as a referent group, providing a metric against which to gauge the impact and course of cancer recurrence.

METHODS

Patients with a newly diagnosed, recurrent (n = 69) or initial (n = 113) breast cancer were accrued. The groups did not differ with regard to age, race, education, family income, or partner status (all P values > .18). All patients were assessed shortly after diagnosis (baseline) and 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months later. Mixed-effects models were used to determine health status, stress, mood, and quality-of-life trajectories.

RESULTS

In the year after a recurrence diagnosis, patients' physical health and functioning showed no improvement, whereas quality of life and mood generally improved, and stress declined. Compared with patients who were coping with their first diagnosis, patients with recurrence had significantly lower anxiety and confusion. In contrast, physical functioning was poorer among recurrence patients, quality-of-life improvement was slower, and cancer-related distress was high as that of the initially diagnosed patient. Slower quality-of-life recovery was most apparent among younger patients (aged <54 years).

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the physical burden, patients with recurrent breast cancer exhibit considerable resilience, with steady improvements in psychological adjustment and quality of life during the year after diagnosis. Management of patients' physical symptoms is particularly important, because patients cope with recurrent breast cancer as a chronic illness.

Keywords: breast, cancer, recurrence, psychological stress, distress, quality of life, functional status, longitudinal

Understanding the changing psychosocial needs of cancer patients is needed to offer timely, targeted interventions.1,2 Of all phases in the illness trajectory, recurrence has profound consequences. Descriptive data from the time of recurrence diagnosis suggest that it can bring loss of hope for recovery, fears of death, and difficulty with disability.3–6 Weisman and Worden1 noted that psychosocial and nonmedical problems, which predominate in the initial diagnosis, give way to physical sickness and existential concerns. Aside from these descriptions, the course of psychological responses and quality-of-life outcomes after recurrence has received little study.

Two studies provided assessments of patients on 2 occasions. Given and Given7 reported that patients who were diagnosed with a recurrence had a decline in functional status from diagnosis to 6 months but that symptom distress and depressive symptoms improved. Bull et al.8 reported that overall quality of life (1 item) and emotional distress (a composite of 4 items) improved from the time of diagnosis to a 6-month follow-up. Other than these 2 studies, a partial picture can be gleaned from patients in the standard care arm in randomized trials of psychological interventions; these data suggest that quality of life is stable in the months after a recurrence diagnosis.9,10 In summary, to our knowledge, no study has assessed recurrence patients at diagnosis and followed them with multiple assessments. A comprehensive view of patients' physical and psychological health and quality of life is needed.

To understand recurrence within the context of the disease trajectory, comparison with the initial diagnosis and treatment would be useful. The challenges of the first diagnosis of cancer long have been known, because many longitudinal studies have demonstrated similar trajectories. Namely, the initial diagnosis is accompanied by significant but time-limited stress, distress, physical symptoms, and impaired quality of life.11–13 Improvements follow quickly, by 3 to 6 months, with further, modest gains through 12 months.14–20 Only 3 studies have compared initial diagnosis and recurrence diagnosis groups.7,15,21 Two cross-sectional studies reached different conclusions: The first study reported equivalent levels of psychological distress,5 and the second reported higher rates of psychiatric diagnoses among breast cancer patients with recurrence.15 The only repeated measures study7 reported smaller improvements for recurrent patients in depression and symptom distress during a 6-month period and larger improvements for the initially diagnosed patients.

The current report provides a description and analysis of patient adjustment after a first recurrence of breast cancer. Physical, psychological, and quality-of-life data are examined. First, longitudinal data from shortly after the diagnosis through 12 months identify domains that present the greatest difficulty and indicate whether difficulties in these domains dissipate over time. Second, the trajectories of patients with a first recurrence are compared with those of patients facing their initial diagnosis. To provide additional clinical detail, we explore patient factors that may contribute to their trajectories.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Procedures

Consecutive new cases of breast cancer were identified through oncology clinics in a university-affiliated, National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Exclusion criteria included prior cancer diagnosis (other than initial breast cancer for the recurrence patients); refusal of cancer treatment; age <20 years or >85 years; residence >90 miles from the research site; and diagnoses of mental retardation, severe or untreated psychopathology, neurologic disorders, dementia, or any immunologic condition/disease. After informed consent was obtained, patients completed face-to-face interviews and questionnaires assessing stress, mood, and quality of life. A research nurse completed a health evaluation. Assessments were repeated every 4 months for 1 year.

Patient Groups

Recurrence diagnosis

Patients who were diagnosed with their first recurrence were sought for the recurrence diagnosis (RD) group. Ninety-one eligible patients were screened, and 69 patients (76%) were accrued. There were no significant differences between participants (n = 69) versus nonparticipants (n = 22) on sociodemographics (race and age), disease characteristics (stage, number of positive lymph nodes, hormone receptor status, tumor classification at initial diagnosis, disease-free interval, and location of recurrent disease), or cancer treatments received (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy, and bone marrow transplantation; all P values > .25). Partner status was the only exception. The patients without a partner/spouse were more likely to participate (chi-square = 4.5; P = .04).

The sample was primarily Caucasian (88%; African American, 12%), middle aged (mean ± standard deviation, 53 ± 11 years), married/partnered (68%), and had some college education (70%). The average disease-free interval was 56 months (range, 7−254 months; median, 35 months), and baseline assessments were performed an average of 11 weeks after diagnosis. The majority of patients (65%) had distant rather than locoregional metastases (see Table 1). By 12 months, 51 patients (74%) continued on the study (13 deaths, 1 second recurrence, and 4 withdrawals).

TABLE 1.

Location of Disease for the Recurrence Diagnosis Group (n = 69)

| Location | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Local | 16 (23) |

| Chest wall | 6 |

| Breast tissue | 10 |

| Regional | 8 (12) |

| Ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes | 5 |

| Supraclavicular lymph nodes | 3 |

| Distant | 45 (65)* |

| Lung | 12 |

| Liver | 14 |

| Bone | 28 |

| Pleura | 3 |

| Brain | 2 |

| Intestine | 1 |

| Peritoneum | 2 |

| Skin | 1 |

Sites of distant disease total > 45, as some patients recurred at multiple sites.

Initial diagnosis

Participants for the initial diagnosis (ID) group (n = 113) were in the standard care arm of an ongoing randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of a psychological intervention for newly diagnosed patients with regional disease.14 There were no significant differences between participants versus nonparticipants with regard to sociodemographics, disease characteristics, or cancer treatments received, as reported previously (all P values > .10).14 The majority of patients in the ID group was Caucasian (90%; African American, 9%; Hispanic, 1%), middle aged (mean standard deviation; 51 ± 11 years), married/partnered (73%), and had some college education (68%). The majority was diagnosed with stage II disease (92%; stage III, 8%). The baseline assessments were performed an average of 8 weeks after diagnosis. By 12 months, 95 patients (84%) remained on the study (2 deaths, 5 recurrences, and 11 withdrawals).

Measures

Health

A research nurse completed 2 measures based on patient interview, medical chart review, and, if needed, physician consultation. 1) Karnofsky performance status (KPS),22 which is a functional status scale ranging from 100 (normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease) to 0 (dead) with 10-point intervals, and 2) symptoms, signs, illnesses, and toxicities, which were assessed by using a rating of common symptoms/signs of illness and cancer treatment toxicities.23 Twenty-two body categories (eg, gastrointestinal, neurosensory) are evaluated, each with from 4 to 7 symptom/sign items (eg, nausea, infection), and are rated on a 5-point scale (from 0 [none] to 4 [life threatening]). Items were averaged for a total score. Internal consistency was .83.

Quality of life

The Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form (SF-36)24 assesses health-related quality of life. Eight subscales measure physical functioning, physical role functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting better quality of life. Internal consistency ranged from .75 to .88.

Mood

The Profile of Mood States-Short Form (POMS)25 is a 37-item self-report inventory assessing mood with 6 scales: Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Vigor, Fatigue, and Confusion. Higher scores on all subscales except Vigor indicate greater distress. Internal consistency ranged from .81 to .92.

Stress

Cancer-specific stress

The Impact of Events Scale (IES)26 is a 15-item scale that examines intrusive thoughts and avoidant thoughts/behaviors related to traumatic events. Items were modified to assess the stress of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Scores >19 reflect clinically relevant levels of stress.27 Internal consistency was .87.

Global stress

The Perceived Stress Scale-10 item version (PSS-10)28,29 measures an individual's appraisal of his or her life as stressful (ie, unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming). Internal consistency was .86.

Analytic Strategy

Mixed-effects models30 were used to describe the trajectories during the first year after recurrence diagnosis and to test for differences in trajectories between the RD and ID groups. To explore individual differences among patients that may relate to risk for psychosocial disruption, the analysis also considered patients' age at diagnosis. “Younger” and “older” patient groups were determined by using the median age of each diagnosis group (50 years for the ID group and 54 years for the RD group). Mean ages for the younger and older groups were 43 years and 60 years in the ID group and 45 years and 63 years in the RD group. Fixed-effects (group average effects) were estimated by using data from all participants. The form of change, linear versus quadratic, was determined by a comparison of the relative fit of the models using a likelihood ratio test. If the fit of the quadratic model was not significantly better (α = .05) than the fit of the linear model, then the linear model was retained.

Each model estimated at least 3 main effects (diagnosis group, age group, and time) and 3 interactions (diagnosis × time, age × time, and diagnosis × age × time). For models of curvilinear change, a quadratic term and diagnosis × quadratic term were added. If the highest order terms (ie, diagnosis × age × time and diagnosis × quadratic term) did not improve the model fit, then those terms were dropped from the final model for parsimony.31 Chemotherapy, radiation, and partner status were considered as controls in all models.

RESULTS

Descriptive

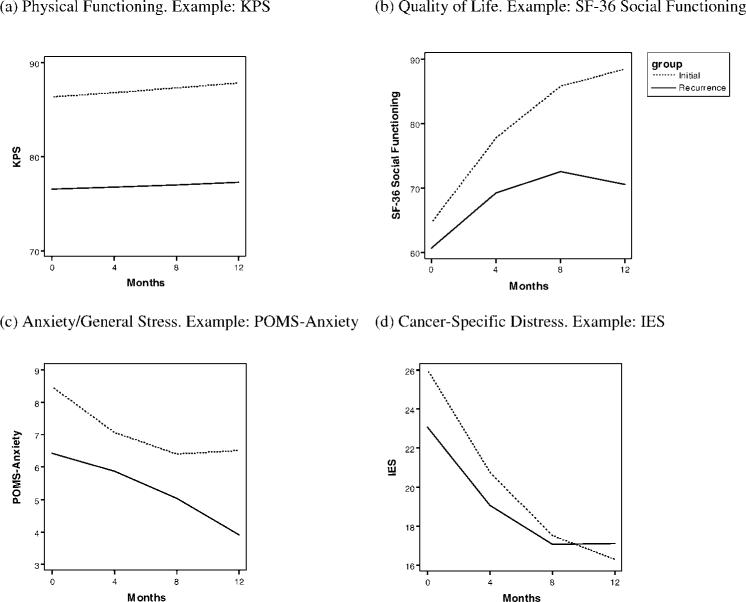

The RD and ID groups did not differ on race, age, education, family income, or partner status (all P values > .18). Figure 1 shows the proportions of patients that received cancer treatments at each assessment. The treatment data reflect the differences in standard therapies for initial versus recurrence diagnoses. For example, at baseline, all patients in the ID group were postsurgery, whereas only 29% of patients in the RD group were postoperative. The majority of ID patients (83%) received chemotherapy between baseline and 4-month assessment only, and all chemotherapy was completed by 12 months. In contrast, large proportions of the RD group (45%−67%) were on chemotherapy throughout the study period. Descriptive statistics for the outcomes at initial presentation and at 12-month follow-up, along with available normative data, are provided in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

The proportions of patients in the recurrence diagnosis group (a) and in the initial diagnosis group (b) that underwent surgery, received chemotherapy, and received radiation therapy at each assessment.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive Data at Baseline and at 12-Month Follow-up for the Recurrence Diagnosis and Initial Diagnosis Groups

|

Mean (standard deviation) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Recurrence diagnosis, n = 69 |

Initial diagnosis, n = 113 |

||||

| Outcome | Baseline | 12 Months | Baseline | 12 Months | Norms |

| Health | |||||

| KPS* | 76.57 (10.52) | 79.00 (12.13) | 86.55 (6.91) | 87.79 (9.13) | 80† |

| Symptoms/signs‡ | 0.27 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.10) | 0.20 (0.12) | 0.25 (0.10) | |

| Quality of Life (SF-36)* | |||||

| Physical Functioning | 61.91 (28.81) | 63.23 (25.61) | 76.98 (18.66) | 81.69 (22.59) | 82.86 (21.72)§ |

| Role Functioning-Physical | 20.22 (32.11) | 41.13 (39.55) | 17.48 (30.60) | 67.44 (39.12) | 79.93 (35.38)§ |

| Bodily Pain | 52.40 (27.97) | 60.13 (28.88) | 47.75 (22.91) | 72.85 (23.41) | 72.14 (23.34)§ |

| General Health | 54.93 (22.12) | 56.74 (25.44) | 68.91 (20.86) | 71.20 (20.32) | 70.48 (20.58)§ |

| Vitality | 42.65 (21.10) | 48.67 (22.05) | 44.38 (21.77) | 59.24 (21.23) | 60.62 (21.32)§ |

| Social Functioning | 60.26 (27.20) | 73.63 (26.85) | 64.20 (24.35) | 89.36 (16.47) | 82.71 (20.84)§ |

| Role Functioning-Emotional | 52.45 (44.36) | 72.04 (38.58) | 51.33 (42.50) | 81.78 (31.79) | 82.86 (21.72)§ |

| Mental Health | 66.65 (18.55) | 78.80 (14.06) | 65.82 (19.04) | 76.98 (14.12) | 79.93 (35.38)§ |

| Mood (POMS)‡ | |||||

| Anxiety | 6.43 (4.96) | 4.16 (2.83) | 8.51 (5.11) | 6.41 (4.85) | |

| Depression | 6.24 (5.74) | 3.45 (3.81) | 6.32 (5.49) | 4.74 (5.38) | |

| Anger | 4.68 (4.68) | 3.52 (3.70) | 5.01 (4.46) | 4.70 (3.99) | |

| Confusion | 4.27 (3.64) | 4.12 (0.44) | 5.72 (4.07) | 4.01 (3.14) | |

| Fatigue | 7.37 (5.37) | 6.58 (3.95) | 6.93 (4.69) | 6.27 (4.75) | |

| Vigor* | 9.73 (5.26) | 11.03 (4.93) | 12.00 (5.36) | 13.86 (4.72) | |

| Stress‡ | |||||

| Cancer-Specific Stress (IES) [% >19] | 23.00 (15.46) [54] | 14.45 (14.40) [35] | 26.28 (14.46) [65] | 15.42 (13.20) [33] | >19∥ |

| Global Stress (PSS-10) | 16.14 (6.46) | 12.90 (5.76) | 18.13 (6.93) | 14.58 (6.51) | 13.02 (6.35)¶ |

KPS, Karnofsky performance status; SF-36, the Medical Outcomes Study—Short Form; POMS, Profile of Mood States; IES, Impact of Events Scale; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale, 10-item version.

For KPS, SF-36, and POMS-Vigor, higher numbers indicate better functioning.

Normal activity with effort; some signs/symptoms.

For symptoms/signs, the remaining POMS scales, and stress, higher numbers indicate poorer functioning.

National norms were based on 193 women ages 45 to 54 years (Ware 200024).

“High stress” (see Horowitz 198227).

National probability sample of adults (Cohen 198848).

Mixed-effects Models

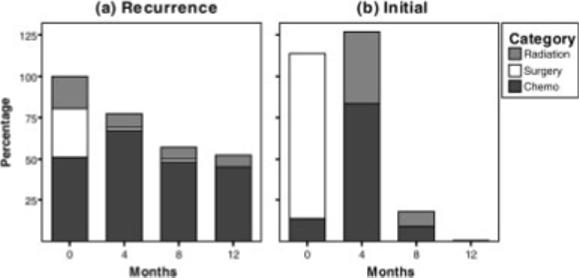

Table 3 summarizes the significant effects from the mixed-effects models. First, we describe the trajectories of the RD group; then, the tests of group differences are described. Illustrative results are shown in Figure 2.

TABLE 3.

Summary of Significant Effects (P < .05) From Mixed-effects Models*

| Variable/Effect | Estimate | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | |||

| Performance status†,‡ | |||

| Diagnosis§ | 8.951 | 1.238 | 7.229 |

| Symptoms/signs†,‡ | |||

| Diagnosis | −0.042 | 0.016 | −2.611 |

| Age∥ | −0.038 | 0.016 | −2.388 |

| Diagnosis × time | 0.006 | 0.002 | 3.692 |

| Quality of life | |||

| Physical Functioning†,‡ | |||

| Diagnosis | 12.763 | 3.415 | 3.738 |

| Role Functioning-Physical‡ | |||

| Time | 5.660 | 1.881 | 3.009 |

| Diagnosis × time | 6.620 | 2.318 | 2.856 |

| Diagnosis × quadratic term | −0.475 | 0.177 | −2.685 |

| Diagnosis × age × time | 2.643 | 1.203 | 2.198 |

| Bodily Pain† | |||

| Age | −7.993 | 3.465 | −2.307 |

| Time | 3.576 | 0.758 | 4.720 |

| Quadratic term | −0.224 | 0.047 | −4.794 |

| Diagnosis × age × time | 1.657 | 0.735 | 2.256 |

| General Health† | |||

| Diagnosis | 12.747 | 3.082 | 4.136 |

| Vitality‡ | |||

| Time | 2.024 | 0.550 | 3.681 |

| Quadratic term | −0.153 | 0.038 | −4.067 |

| Diagnosis × time | 0.841 | 0.323 | 2.601 |

| Social Functioning† | |||

| Time | 2.599 | 0.751 | 3.461 |

| Quadratic term | −0.166 | 0.054 | −3.085 |

| Diagnosis × time | 1.275 | 0.382 | 3.337 |

| Mental Health | |||

| Time | 2.078 | 0.396 | 5.250 |

| Quadratic term | −0.088 | 0.026 | −3.427 |

| Mood | |||

| Anxiety | |||

| Diagnosis | 2.080 | 0.771 | 2.697 |

| Diagnosis × quadratic term | 0.034 | 0.016 | 2.107 |

| Depression† | |||

| Time | −0.161 | 0.071 | −2.263 |

| Anger | |||

| Age | 1.511 | 0.622 | 2.429 |

| Confusion | |||

| Diagnosis | 1.154 | 0.547 | 2.109 |

| Vigor†,‡ | |||

| Diagnosis | 1.623 | 0.783 | 2.072 |

| Stress | |||

| Cancer-Specific Stress | |||

| Time | −1.406 | 0.321 | −4.373 |

| Quadratic term | 0.063 | 0.023 | 2.891 |

| Global Stress | |||

| Time | −0.773 | 0.149 | −5.203 |

| Quadratic term | 0.039 | 0.010 | 3.828 |

SE indicates standard error.

Note. Each model tested all relevant main and interaction effects, as detailed in the text. However, for space-saving purposes, only significant effects for each model are reported in this table.

A significant main effect of partner status was identified for these variables, indicating that patients without a partner had poorer functioning than patients with a partner.

A significant main effect of chemotherapy was identified for these variables, indicating that patients who received chemotherapy had poorer functioning than patients who did not receive chemotherapy.

Recurrent versus initial diagnosis groups.

Younger versus older patient groups.

FIGURE 2.

Four patterns of change are illustrated. (a) The first pattern was observed in Karnofsky performance status (KPS), in quality of life related to the Physical Functioning and General Health scales, and in the Profile of Mood States (POMS)-Vigor subscale. (b) The second pattern was observed in quality of life related to the Vitality, Social Functioning, and Role Functioning-Physical subscales. (c) The third pattern was observed in the POMS Anxiety and Confusion sub-scales and in global stress on the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale. (d) The fourth pattern was observed in cancer-specific stress on the Impact of Event Scale (IES), on the POMS Depression subscale, and on quality of life related to the Mental Health and Role Functioning-Emotional subscales. SF-36 indicates the Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form.

Recurrence trajectories

With regard to evaluations of the patients' health, the baseline performance status (KPS) was in the 70 to 80 range (ie, “unable to carry on normal activity or do active work” to “normal activity with effort; some signs/symptoms”), and there was no improvement during follow-up (P = .753). With respect to the symptoms/signs, only a trend of quadratic change was observed (P = .060), in that symptoms/signs increased during the first 4 months and then decreased between 4 and 12 months.

Of the quality-of-life domains, Physical Functioning (P = .968), General Health (P = .092), and Role Functioning-Emotional (P = .137) showed similar trajectories with no improvement. The remaining SF-36 subscales—Role Functioning-Physical, Bodily Pain, Vitality, Social Functioning, and Mental Health—showed significant improvements (all P values <.003). With regard to the POMS mood scales, a significant improvement was observed in Depression (P = .025), but no changes were observed in Anxiety, Anger, Confusion, Fatigue, or Vigor (P > .146).

With regard to stress, patients reported a ‘high’ level (mean, 23) of cancer-specific stress (IES) at baseline according to normative data.27 However, stress significantly decreased (P < .001), and the shape of change was curvilinear (P = .004), with the largest reduction in stress occurring from baseline to 4 months. A similar effect was observed with global stress; the PSS-10 score decreased (P < .001), with the greatest change apparent in the early months of follow-up (P < .001).

In summary, both nurse-rated and patients evaluations of health showed no improvement during the year after the recurrence diagnosis. Despite this, patients' quality of life and depressed mood improved, and stress declined significantly.

Contrasts of trajectories after recurrence and initial diagnosis

The baseline performance status (KPS) for the RD group was significantly lower than that for the ID group (P < .001), which had mean scores that corresponded to the 80 to 90 range (ie, from “normal activity with effort; some signs/symptoms” to “able to carry on normal activity; minor signs/symptoms”). There was no difference between groups in the pattern of change (P = .731) (see Fig. 2a); thus, the baseline group difference remained throughout the follow-up. There were no significant differences in the trajectories between age groups (P > .358).

The RD group also had significantly more symptoms/signs at baseline than the ID group (P = .010), and the groups differed significantly in patterns of change (P < .001). The RD group had only a slight increase in symptoms during the first 4 months, followed by a return to baseline at 8 months; whereas the ID group had a rapid increase in symptoms/signs during the first 4 months (the time when chemotherapy was administered) and then had a slight decrease. Although the RD group had significantly greater symptoms/signs at baseline, the groups converged by 12 months. The older patient group, regardless of the diagnosis, had significantly more symptoms/signs at baseline than the younger group (P = .018); and, although the levels of symptoms changed across time, this difference between age groups remained.

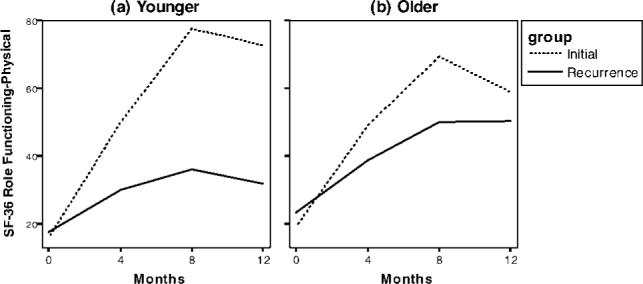

With regard to quality of life, both Physical Functioning and General Health scores were significantly lower for the RD group compared with the ID group at baseline (P < .001). There were no group differences in the rate of change (P > .169), so these group differences were maintained throughout the follow-up (see Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences between the age groups (P > .070). For Vitality, Social Functioning, Role Functioning-Physical, and Bodily Pain, there were no baseline group differences (P > .150). The rates of recovery were significantly slower among patients in the RD group compared with patients in the ID group for Vitality, Social Functioning (see Fig. 2b), and Role Functioning-Physical (P < .010). The younger patients had significantly more bodily pain at baseline than older patients (P = .022). For both Role Functioning-Physical and Bodily Pain, significant 3-way interactions were observed, in that the recovery of younger patients in the RD group was significantly slower than the recovery in the 3 other groups (P values < .029) (see Fig. 3). Finally, for Mental Health and Role Functioning-Emotional, there were no significant differences in the trajectories of the diagnosis groups or the age groups (P > .102).

FIGURE 3.

Slower recovery in quality of life was most apparent among younger patients in the recurrence diagnosis group, as illustrated with the Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form (SF-36) Role Functioning-Physical sub-scale.

Different patterns were observed for the POMS subscales. Anxiety was significantly lower among the RD group than the ID group at baseline (P = .008), and the groups also differed in their patterns of change (P = .037) (see Fig. 2c). The RD group demonstrated a greater change in anxious mood late (from 8 to 12 months), whereas the ID group demonstrated a greater improvement early (from baseline to 4 months). The baseline Depression of the RD group did not differ significantly from that of the ID group (P = .818), nor was there a significant difference in change over time; although a trend was observed (P = .069), suggesting that the rate of decline was more rapid in the RD group than in the ID group. The RD group had significantly less Confusion at baseline than the ID group (P = .036); and the groups did not differ in the rate of decline (P = .369). The baseline Vigor among patients in the RD group was significantly lower than that for patients in the ID group (P = .040); and, again, there was no group difference in the rate of change (P = .214). For Anger and Fatigue, there were no differences in the trajectories between the RD group and the ID group (P > .274). Finally, the only difference observed between the age groups was that for baseline Anger (P = .016). Younger patients had significantly higher Anger than older patients throughout follow-up without significant change (P = .304).

There were no significant differences in cancer-specific stress (IES) trajectories between diagnosis groups or age groups (P > .142) (see Fig. 2d). For global stress (PSS-10), both baseline differences between the diagnosis groups and between the age groups approached statistical significance (P = .054 and P = .064, respectively). Global stress was lower in the RD group than in the ID group and was lower in older patients than in younger patients throughout follow-up with no group differences in the rate of decline (P > .662).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the physical, psychological, and quality-of-life trajectories of patients who were diagnosed with recurrent breast cancer. Moreover, their trajectories are contrasted with those from patients who were coping with an initial diagnosis. Patients exhibited substantial stress, physical symptoms, and quality-of-life impairment in the early weeks after diagnosis, as expected. For those who were diagnosed with a recurrence, there was little change (improvement) in physical functioning over the next 12 months. Despite this, these patients improved across psychological and quality-of-life domains, highlighting their resilience in coping with recurrence.

In the current study, we also compared the trajectories of the ID group and the RD group. Four patterns emerged, and each is illustrated. First, nurse-rated and self-reported measures indicated that the RD group had poorer physical functioning relative to the ID group (see Fig. 2a). Prior studies have documented pain32 and appetitive difficulties (eg, anorexia, cachexia33) with recurrence, and the current data confirm the functional differences reported in cross-sectional and shorter term studies.5,7 Patients did receive symptom management treatments (eg, erythropoietin, growth factors, antiemetics), possibly accounting for the stable (rather than increasing) symptom levels; however, the data suggest that additional intervention may be needed. Psychological and behavioral interventions may be used as adjuncts, because they can improve functional status, reduce symptoms,34 and treat specific symptoms (eg, fatigue, pain).35–37

The second pattern (see Fig. 2b) suggests that the physical burdens associated with a recurrence diagnosis may hamper, but not prevent, the return of health-related quality of life. Patients in both groups reported increasing energy, less health-related interference with their social and role functioning (eg, visiting friends/relatives, accomplishing tasks), and less disruption because of pain over time. However, health-related quality-of-life recovery was slower for patients who were diagnosed with recurrence. Prior research21 has indicated that quality of life can be affected at the time of a recurrence diagnosis; and the current data extend that finding and show that quality of life improves modestly with time.

The third pattern illustrated that patients who were coping with recurrence reported less anxiety and confusion and marginally less perceived stress than patients who were coping with an initial diagnosis (see Fig. 2c). This pattern was observed with the baseline assessment, and it continued through the next 12 months. We have hypothesized that patients' familiarity with the cancer experience would ease the psychological impact at the time of the recurrence diagnosis.38 Knowledge of the challenges associated with cancer treatment (eg, disruption of daily routines, immersion in the medical system) likely lessens stress, anxiety, and uncertainty. Moreover, sources of support and help that were identified at the time of the initial diagnosis (eg, family/friends, oncologist, psychologist, physical therapist) may be called on more readily.

The final pattern indicated that newly diagnosed patients—both with an initial diagnosis and with a recurrence diagnosis—had comparable, high levels of cancer-specific stress and distress (see Fig. 2d). The mean values observed on the IES23–26 were high, comparable to those of patients seeking treatment for anxiety disorders27 and consistent with prior data.21 Although cancer-related stress declined, it remained at or above the clinical cutoff for patients as long as 8 months after diagnosis. Taken together, the data suggest that, although specific concerns may change from the initial to the recurrence diagnosis, the absolute levels of cancer-specific stress, depressed mood, and sense of impairment from emotional difficulties are equivalent.

Our sample sizes enabled a comparison of patients in their middle 40s with patients in their early 60s, and relatively few differences emerged. Older patients, as expected, had more physical symptoms. However, physical symptomatology appeared to have a more disruptive effect on quality of life for younger patients compared with older patients, as observed in the significant interactions for the Role Functioning-Physical and Bodily Pain scales. It is noteworthy, however, that these impairments and the slowed recovery occurred only for the younger patients who were coping with recurrence (see Fig. 3). In addition, these effects remained apparent even after controlling for other factors that covary with age and physical functioning: namely, cancer treatment and partner status. For example, receipt of chemotherapy was associated with poorer physical status; and, although younger patients were more likely to receive chemotherapy than older patients, young age predicted physical impairment beyond that caused by chemotherapy. Similarly, the presence of a significant other, which is more likely for patients who are younger and which has a protective effect on health,39 was not sufficient in this study. Finally, the data suggest that younger women at both diagnoses were angrier with the situation (or perhaps were more apt to express their anger). Taken together, however, the findings with these age groups do not suggest a particular vulnerability for the newly diagnosed cancer patients who are “younger” versus “older.” Instead, the data suggest that “younger” women who are diagnosed with recurrence may have greater psychosocial disruption.

Finally, the current data suggest that many of the psychological interventions that have been tested with patients who were coping with their initial diagnosis40–43 also should be useful to patients who are coping with a recurrence, albeit with modifications. First, because symptoms and physical impairment may be ever present, more strategies that improve symptoms are needed. Strategies such as progressive muscle relaxation, hypnosis, and exercise, for example, have demonstrated efficacy.34,35,44 Second, interventions for coping with cancer need to be tailored to address the limitations that are posed by physical symptoms. In particular, patients who become more distressed because of their physical symptoms are then at risk for a slowed return of social and emotional quality of life.45 Enhancing patients' relationships with friends and family members would be an important intervention target, because data suggest that patients whose poor health prevents social activity report less meaning in life and, in turn, greater distress.46 Third, when symptom stress is high, it is more likely that individuals will cope through problematic strategies and/or that they will fail to engage in activities that would be helpful.47 Thus, in addition to the standard treatment of teaching engagement coping (eg, seeking social support, positive reinterpretation of events), the third modification would be to forewarn patients that they may slip into disengagement coping (eg, denial, withdrawal from activities or people, substance use) when they are troubled with their physical limitations.

In conclusion, the current study highlights a first recurrence of cancer as qualitatively different from the initial diagnosis. Despite a poor prognosis, aggressive cancer therapies, and physical symptoms, patients with disease recurrence report gains in their psychological functioning and quality of life. This positive course is slowed for younger patients with recurrence. Modification of existing psychological interventions to incorporate symptom management or active coping with symptoms appears important and is feasible. Psychological treatments must evolve to address recurrent cancer as a chronic condition as improved cancer therapies are transforming recurrence from a rapidly progressing condition to a chronic illness. Comprehensive efforts are needed to achieve an optimal quality of life for patients who survive recurrent cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for their participation and continuing commitment and the research staff of the Stress and Immunity Cancer Projects.

Supported by a grant from the American Cancer Society (PBR-89); Longaberger Company-American Cancer Society Grant for Breast Cancer Research (PBR-89A and RSGPB-03-248-01-PBP); U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Grants DAMD17-94-J-4165, DAMD17-96-1-6294, and DAMD17-97-1-7062; National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH51487); and National Cancer Institute (R01-CA92704, KO5-CA098133, and P30-CA16058).

REFERENCES

- 1.Weisman AD. A model for psychosocial phasing in cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1979;1:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(79)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.President's Cancer Panel . Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, Md: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahon SM, Cella DF, Donovan MI. Psychosocial adjustment to recurrent cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1990;17:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahon SM, Casperson DS. Psychosocial concerns associated with recurrent cancer. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:372–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munkres A, Oberst MT, Hughes SH. Appraisal of illness, symptom distress, self-care burden, and mood states in patients receiving chemotherapy for initial and recurrent cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1992;19:1201–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisman AD, Worden JW. The emotional impact of recurrent cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1985;3:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Given B, Given CW. Patient and family caregiver reaction to new and recurrent breast cancer. JAMA. 1992;47:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bull AA, Meyerowitz BE, Hart S, Mosconi P, Apolone G, Liberati A. Quality of life in women with recurrent breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;54:47–57. doi: 10.1023/a:1006172024218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herth K. Enhancing hope in people with a first recurrence of cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1431–1441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Northouse LL, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A. Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2005;14:478–491. doi: 10.1002/pon.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broeckel JA, Jacobsen PB, Balducci L, Horton J, Lyman GH. Quality of life after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;62:141–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1006401914682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Stress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:30–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michael YL, Kaqwachi I, Berkman LF, Holmes MD, Colditz GA. The persistent impact of breast carcinoma on functional health status: prospective evidence from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer. 2000;89:2176–2186. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2176::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes following a psychosocial intervention: a clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;17:3570–3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: 5 year observational cohort study [abstract]. BMJ. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire GP, Lee EG, Kuchemann CS, Crabtree RJ, Cornell CE. Psychiatric problems in the first year after mastectomy. BMJ. 1978;1:963–965. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6118.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen BL, Anderson B, deProsse C. Controlled prospective longitudinal study of women with cancer: II. Psychological outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:692–697. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.6.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol. 2004;23:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stommel M, Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given BA. A longitudinal analysis of the course of depressive symptomatology in geriatric patients with cancer of the breast, colon, lung, or prostate. Health Psychol. 2004;23:564–573. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornton LM, Andersen BL, Crespin TR, Carson WE., III Individual trajectories in stress covary with immunity during recovery from cancer diagnosis and treatments. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen BL, Shapiro CL, Farrar WB, Crespin TR, Wells-Di Gregorio SM. Psychological responses to cancer recurrence: a controlled prospective study. Cancer. 2005;104:1540–1547. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: Macleod CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; New York, NY: 1949. pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moinpour CM, Feigl P, Metch B, Hayden KA, Meyskens FL, Crowley J. Quality of life end points in cancer clinical trials: review and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:485–495. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.7.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. QualityMetric Inc; Lincoln, RI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curran SL, Andrykowski KJ, Studts JL. Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): psychometric information. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horowitz MJ. Stress response syndromes and their treatment. In: Goldberger L, Breznitz S, editors. Handbook of Stress. The Free Press; New York, NY: 1982. pp. 711–732. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golden-Kreutz DM, Browne MW, Frierson GM, Andersen BL. Assessing stress in cancer patients: a second-order factor analysis model for the Perceived Stress Scale. Assessment. 2004;11:216–223. doi: 10.1177/1073191104267398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, Calif: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Stat Med. 1997;16:2349–2380. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::aid-sim667>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353:1695–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Body JJ, Lossignol D, Ronson A. The concept of rehabilitation of cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 1997;9:332–340. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199709040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, et al. Distress reduction from a psychological intervention contributes to improved health for cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel D, Bloom JR. Group therapy and hypnosis reduce metastatic breast carcinoma pain. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:333–339. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198308000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forester B, Kornfield DS, Fleiss JL. Psychotherapy during radiotherapy: effects on emotional and physical distress. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:22–27. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Shaw H, Miller JM. Yoga for women with metastatic breast cancer: results from a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Northouse LL, Laten D, Reddy P. Adjustment of women and their husbands to recurrent breast cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:515–524. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a 9 year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;108:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manne SL, Andrykowski MA. Are psychological interventions effective and accepted by cancer patients? II. Using empirically supported therapy guidelines to decide. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:98–103. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanton AL. How and for whom? Asking questions about the utility of psychosocial interventions for individuals diagnosed with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4818–4820. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:558–584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen BL. Psychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance the quality of life. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:552–568. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider CM, Hsieh CC, Sprod LK, Carter SD, Hayward R. Effects of supervised exercise training on cardiopulmonary function and fatigue in breast cancer survivors during and after treatment. Cancer. 2007;110:918–925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simonelli LE, Fowler J, Maxwell GL, Andersen BL. Physical sequelae and depressive symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors: meaning in life as a mediator. Ann Behav Med. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9029-8. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jim HS, Andersen BL. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12(pt 3):363–381. doi: 10.1348/135910706X128278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang H, Brothers BM, Andersen BL. Stress and quality of life in breast cancer recurrence: moderation or mediation of coping? Ann Behav Med. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9016-0. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, Calif: 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]