Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To assess the knowledge of early childhood caries and to examine the current preventive oral health-related practices and training among Canadian paediatricians and family physicians who provide primary care to children younger than three years.

METHODS

A cross-sectional, self-administered survey was mailed to a random sample of 1928 paediatricians and family physicians.

RESULTS

A total of 1044 physicians met the study eligibility criteria, and of those, 537 returned completed surveys, resulting in an overall response rate of 51.4% (237 paediatricians and 300 family physicians). Six questions assessed knowledge of early childhood caries; only 1.8% of paediatricians and 0.7% of family physicians answered all of these questions correctly. In total, 73.9% of paediatricians and 52.4% of family physicians reported visually inspecting children’s teeth; 60.4% and 44.6%, respectively, reported counselling parents or caregivers regarding teething and dental care; 53.2% and 25.6%, respectively, reported assessing children’s risk of developing tooth decay; and 17.9% and 22.3%, respectively, reported receiving no oral health training in medical school or residency. Respondents who felt confident and knowledgeable and who considered their role in promoting oral health as “very important” were significantly more likely to carry out oral health-related practices.

CONCLUSION

Although the majority of paediatricians and family physicians reported including aspects of oral health in children’s well visits, a reported lack of dental knowledge and training appeared to pose barriers, limiting these physicians from playing a more active role in promoting the oral health of children in their practices.

Keywords: Attitudes, Dental caries, Early childhood caries, Health knowledge, Oral health, Physicians, Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIFS

Évaluer les connaissances sur la carie dentaire dans la petite enfance et examiner les pratiques préventives et la formation actuelles en santé buccodentaire chez les pédiatres et les médecins de famille canadiens qui prodiguent des soins primaires aux enfants de moins de trois ans.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

Une enquête transversale autoadministrée a été postée à un échantillon aléatoire de 1 928 pédiatres et médecins de famille.

RÉSULTATS

Au total, 1 044 médecins respectaient les critères d’admissibilité à l’étude et, de ce nombre, 537 ont renvoyé un questionnaire rempli, ce qui a donné un taux de réponse globale de 51,4 % (237 pédiatres et 300 médecins de famille). Six questions permettaient d’évaluer les connaissances sur la carie dentaire dans la petite enfance. Seulement 1,8 % des pédiatres et 0,7 % des médecins de famille ont répondu correctement à toutes ces questions. En total, 73,9 % des pédiatres et 52,4 % des médecins de famille ont déclaré inspecter visuellement les dents des enfants; 60,4 % et 44,6 %, respectivement, ont déclaré donner des conseils aux parents ou aux gardiennes au sujet de la poussée des dents et de l’hygiène dentaire; 53,2 % et 25,6 %, respectivement, ont déclaré évaluer le risque que l’enfant développe une carie dentaire; et 17,9 % et 22,3 %, respectivement, ont déclaré n’avoir reçu aucune formation en santé buccodentaire à la faculté de médecine ou en résidence. Les répondants qui se sentaient confiants et au courant et qui jugeaient leur rôle « très important » dans la promotion de la santé buccodentaire étaient considérablement plus susceptibles d’adopter des pratiques reliées à la santé buccodentaire.

CONCLUSION

Même si la majorité des pédiatres et des médecins de famille déclaraient inclure des aspects de la santé buccodentaire dans leurs consultations auprès d’enfants en santé, une absence déclarée de connaissances et de formation en santé dentaire semblait provoquer des obstacles et empêcher ces médecins de jouer un rôle plus actif dans la promotion de la santé buccodentaire des enfants de leur pratique.

Early childhood caries (ECC) is a particularly virulent form of dental caries affecting the primary teeth of infants and toddlers. Prolonged ad libitum bottle-feeding with sugar-containing fluids, especially before sleep, and delayed weaning are frequently cited ECC risk factors (1–4). Epidemiological studies have also documented low socioeconomic status, minority status (5–7), low birth weight (8) and transfer of microbes from mother to child through the sharing of spoons and soothers as ECC risk factors (9,10). One per cent to 12% of children younger than six years in the developed world experience ECC. In developing countries and within disadvantaged populations in developed countries, the prevalence of ECC is as high as 70% (11). The prevalence among five-year-old children in Canada is estimated to be 10%; among those born outside Canada, it is 14.5% (12) and among Aboriginal children, it is 85% (13).

Children with ECC have difficulty chewing and eating. In addition, these children often need dental treatment under general anesthesia, incurring heavy costs to the family and the health care system (14). The average cost of treating one child with ECC in Canada ranges from $700 to $3,000, and the total cost is even higher if indirect costs, such as medical evacuation from small communities to larger centres, are included (15).

Not all children have access to professional dental care. Contact of a child with a family physician or paediatrician typically occurs earlier than a child’s first visit to a dental care provider. On average, children are seen 11 times for well visits with a physician by three years of age (16). Guidelines advise primary health care providers to counsel families on teething and dental care, and to recommend the timing of the first dental visit (17,18). However, little is known about the preventive dental care practices of Canadian family physicians and paediatricians, the extent of oral health education and training they receive during medical school and residency training, and what knowledge of ECC and its preventive aspects these health professionals actually possess. A limited number of studies have examined the knowledge and attitudes of physicians regarding ECC or preventive dental care for children (19–25); however, no Canadian studies exist.

The purpose of the current study was to assess the knowledge of ECC among paediatricians and family physicians in Canada who provide well care for children younger than three years; to examine the proportions of physicians who reported performing oral health-related practices during well care visits for this age group; and to determine what oral health education paediatricians and family physicians received during medical and specialty training. In addition, the willingness of these professionals to support oral health-promotion activities and barriers to performing these activities were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional, English-language survey of a nationwide random sample of 964 paediatricians and 964 family physicians was conducted using a mailed, self-administered questionnaire. The study populations were paediatricians and family physicians in Canada who provide well care to children younger than three years. The sample size was based on a previous study of American paediatricians by Lewis et al (24) and pilot study findings. Samples were obtained from the databases provided by the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) and the College of the Family Physicians of Canada. Participants received a six-page questionnaire, a covering letter and an addressed, stamped return envelope. Using a modified Dillman’s method (26), up to four contacts were made: a first mailing to all subjects followed by two subsequent mailings to nonrespondents and one final attempt to contact by phone.

The questionnaire was developed based on a literature review, pilot testing at the CPS 79th annual meeting, and a review by experts to further assess its face and content validity. The questionnaire had four sections, reflecting themes emerging from the pretests. Respondents whose practices did not include well care for children younger than three years were asked to check an indicated box on the questionnaire and return the survey. Physicians who did not wish to participate were asked to return a blank survey. The questionnaire’s first section collected information on current oral health-related practices. Physicians were asked to estimate the prevalence of ECC in their practice and the frequency of oral health-related tasks during a child’s well visit (ie, visual examination of the oral cavity, specific visual examination of the teeth, counselling parents or caregivers regarding teething and dental care, assessing a child’s risk of developing tooth decay and recommending the child’s first dental visit). The first section also had six knowledge-based questions and two self-rated knowledge and confidence questions regarding ECC that used a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, not sure, agree and strongly agree). The second section addressed family physicians’ and paediatricians’ willingness to provide oral screenings, counselling and referrals, as well as the perceived importance of their role in promoting oral health (very important, somewhat important, not very important or not important at all). The third section investigated physicians’ oral health education and training, and the fourth section collected background demographic information. The study was approved by the ethics review board at the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario).

Data analysis

Outcome variables were the proportions of paediatricians and family physicians conducting visual examinations of the teeth, counselling parents or caregivers regarding teething and dental care, assessing a child’s risk for developing tooth decay and recommending the first dental visit when the child is younger than one year. The main explanatory variables were the oral health education received during medical and specialty training (received or not, number of hours received, quality rating of their training and continuing medical education (CME) courses on oral health completed in the past five years). The physicians’ and paediatricians’ knowledge of ECC, their confidence level and perceived role in promoting the oral health of young children were other potential explanatory variables. Frequency distributions for proportions and means for continuous variables were generated using SPSS, version 10.1 (SPSS Inc, USA). χ2 analyses were performed to compare categorical variables, and Student’s t tests, or their nonparametric equivalent tests, were performed for continuous variables. Adjusted and unadjusted assessments, including odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals, were calculated with χ2 analysis and logistic regression.

RESULTS

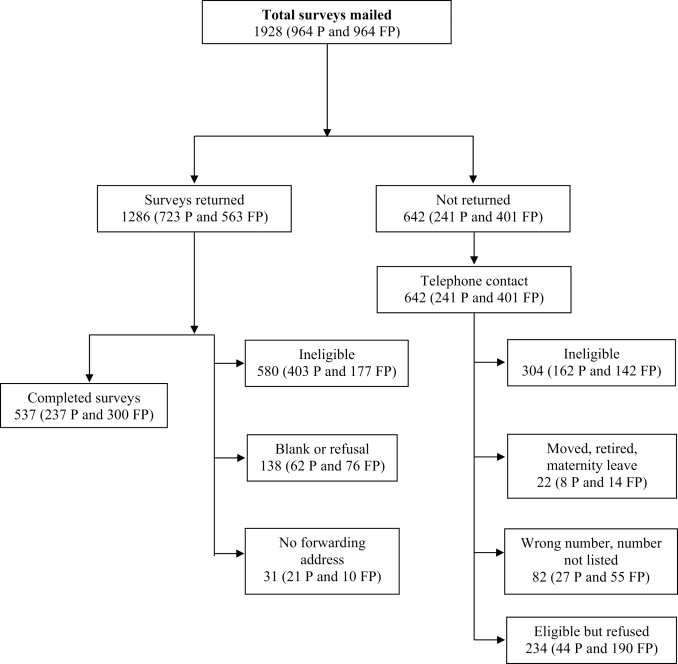

Of 1928 surveys mailed, 31 were returned with no forwarding address, 138 surveys were returned blank and 884 paediatricians and family physicians indicated their ineligibility to complete the survey because they did not provide well care to children younger than three years. Among the 1044 physicians who met the eligibility criteria, 537 completed surveys were returned, giving an overall response rate of 51.4% (237 paediatricians and 300 family physicians) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between early responders (respondents to the first and second mailings) and late responders (respondents to the third mailing) on available demographic variables and other variables of interest.

Figure 1).

Responses obtained from three consecutive mailings and a telephone call. FP Family physicians; P Paediatricians

There were significant differences in demographics and practice characteristics between paediatricians and family physicians (Tables 1 and 2). Paediatricians reported seeing more children for well visits per month and more ECC cases each month than did family physicians.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of paediatricians and family physicians

| Characteristic | Paediatricians (n=237) | Family physicians (n=300) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years in practice | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.8 (10.8) | 13.2 (8.8) | <0.001* |

| Median (interquartile range) | 15.0 (8–25) | 12.0 (5–20) | |

| Hours of patient care per week | |||

| Mean (SD) | 44.5 (16.3) | 40.5 (14.7) | 0.004* |

| Median (interquartile range) | 40.0 (35–50) | 40.0 (30–50) | |

| Office location (%) | |||

| Urban | 74.9 | 51.5 | |

| Suburban | 19.4 | 19.3 | <0.001† |

| Rural | 5.7 | 29.2 | |

| Type of practice (%) | |||

| Solo | 30.4 | 20.9 | <0.001† |

| Group | 51.3 | 72.3 | |

| Hospital-based | 17.4 | 3.0 | |

| Community-based | 0.9 | 3.7 | |

Student’s t test;

χ2 test

TABLE 2.

Practice characteristics of paediatricians and family physicians

| Characteristic | Paediatricians (n=237) | Family physicians (n=300) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well baby visits per month | |||

| Mean (SD) | 97.2 (96.2) | 18.7 (8.8) | <0.001* |

| Median (interquartile range) | 70.0 (20–150) | 15.0 (6–20) | |

| ECC cases per month (%) | |||

| Never | 5.2 | 19.1 | |

| One child every two months or less | 39.2 | 64.4 | <0.001† |

| One to three children per month | 27.2 | 11.7 | |

| Three to five children per month | 17.2 | 2.0 | |

| More than five children per month | 11.2 | 2.7 | |

| Proportion of recent immigrant populations as patients | |||

| Mean, % (SD) | 13.6 (16.6) | 9.6 (17.2) | 0.008‡ |

| Median (interquartile range) | 10.0 (5–20) | 5.0 (1–10) | |

| Proportion of non-English-/non-French-speaking populations as patients | |||

| Mean, % (SD) | 23.1 (30.8) | 11.9 (22.7) | <0.001‡ |

| Median (interquartile range) | 10.0 (5–20) | 3.0 (1–10) | |

| Patients’ ethnic origin (%) | |||

| Caucasian (50% to 100%) | 71.7 | 84.2 | 0.001† |

| African-Canadian (0% to 50%) | 92.4 | 96.0 | 0.264† |

| Asian-Canadian (0% to 50%) | 89.5 | 94.0 | 0.947† |

| First Nations, Inuit or Métis (0% to 50%) | 90.3 | 93.7 | 0.340† |

| Other (0% to 50%) | 90.0 | 96.3 | 0.509† |

Mann-Whitney U test;

χ2 test;

Student’s t test. ECC Early childhood caries

Knowledge of ECC and its preventive aspects

The majority of respondents were aware of the effects of bottle-feeding, the effect of untreated dental decay on the general health of the child and the importance of baby teeth (Table 3). Fifty-three per cent of paediatricians and 57% of family physicians were not sure of the transmission of bacteria from mother to child that causes tooth decay, while 46% of paediatricians and 62% of family physicians were not sure that white spots or lines on tooth surfaces were the first signs of tooth decay. Fewer family physicians felt confident in identifying dental caries and counselling about children’s dental care than did paediatricians. Only 1.8% of paediatricians and 0.7% of family physicians answered all six knowledge questions correctly. There were no significant differences in the overall knowledge scores between the two groups.

TABLE 3.

Knowledge of early childhood caries and confidence in carrying out oral health-related activities among paediatricians and family physicians in Canada

| Knowledge questionnaire item | Response | Paediatricians (%) | Family physicians (%) | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only bottle-fed babies are affected by early childhood tooth decay | Strongly disagree/disagree | 80.3 | 72.8 | |

| Not sure | 6.3 | 16.3 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 13.5 | 10.9 | ||

| Untreated dental decay could affect the general health of the child | Strongly disagree/disagree | 4.0 | 1.0 | |

| Not sure | 2.2 | 3.1 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 93.8 | 95.9 | ||

| Bacteria that cause decay can spread from mother to child | Strongly disagree/disagree | 23.7 | 18.1 | |

| Not sure | 52.7 | 57.0 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 23.7 | 24.9 | ||

| Fluoride toothpaste should not be given to children younger than three years | Strongly disagree/disagree | 52.7 | 48.1 | |

| Not sure | 10.3 | 28.2 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 37.1 | 23.7 | ||

| First signs of tooth decay are white lines or spots on the tooth surfaces | Strongly disagree/disagree | 30.4 | 18.1 | |

| Not sure | 46.1 | 61.8 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 23.5 | 20.1 | ||

| Baby teeth are important even though they fall out | Strongly disagree/disagree | 1.8 | 0.7 | |

| Not sure | 0.4 | 1.7 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 97.8 | 97.6 | ||

| Overall knowledge score*, mean (SD) (range 0 to 12) | 8.24 (1.7) | 8.35 (1.4) | 0.441 | |

|

Confidence questionnaire item | ||||

| I feel confident enough to identify dental caries in children | Strongly disagree/disagree | 21.3 | 36.5 | |

| Not sure | 21.8 | 27.6 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 56.9 | 35.8 | ||

| I feel knowledgeable enough to discuss and counsel parents regarding home dental care for their children | Strongly disagree/disagree | 14.2 | 27.3 | |

| Not sure | 9.3 | 20.8 | ||

| Agree/strongly agree | 76.4 | 51.9 | ||

Each response coded as 0 = incorrect response, 1 = not sure and 2 = correct response;

Student’s t test

Preventive oral health-related practices

Respondents were asked to report the frequency with which they performed oral health-related activities during well visits (Table 4). Most paediatricians and family physicians reported visually examining the oral cavity and inspecting children’s teeth. Fewer respondents reported providing dental counselling to parents or assessing the child’s risk of developing tooth decay. Only 2.7% of respondents reported recommending the first dental visit earlier than one year of age. Both groups of physicians most often advised the parent or caregiver to take the child to a dentist when they identified tooth decay.

TABLE 4.

Oral health-related practices during well baby visits among paediatricians and family physicians in Canada

| Oral health-related practice | Paediatricians (n=237), % | Family physicians (n=300), % | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual oral examination | 87.0 | 69.3 | <0.001 |

| Visual examination of teeth | 73.9 | 52.4 | <0.001 |

| Counsel parent on teething | 60.4 | 44.6 | <0.001 |

| Assess the child’s risk for developing tooth decay | 53.2 | 25.6 | <0.001 |

| First dental visit recommendation for the child | |||

| Do not recommend | 1.3 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| Younger than one year | 2.7 | 2.7 | |

| One to two years | 20.0 | 20.0 | |

| Older than two years to three years | 55.6 | 45.8 | |

| Older than three years | 20.4 | 21.4 | |

| Steps taken when a child with tooth decay is identified | |||

| Never seen a child with tooth decay | 2.5 | 9.4 | <0.001 |

| Do not take any particular steps | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Make a note on the medical chart | 3.4 | 4.0 | |

| Suggest or prescribe treatment | 3.0 | 1.3 | |

| Advise the parent or caregiver to take the child to a dentist | 76.3 | 83.2 | |

| Make a formal referral to a dentist | 14.4 | 2.0 | |

χ2 test

Oral health education and training

Paediatricians and family physicians reported that they gained their oral health education and training mostly through practice experience (Table 5). Only 18.2% of paediatricians and 37.7% of family physicians reported receiving oral health training during medical school. There were significant differences in the number of hours of training, quality of training and number of hours of CME training in oral health topics between the two physician groups (Table 5). Compared with family physicians, paediatricians received more training and attended more CME courses on oral health topics.

TABLE 5.

Oral health education and training received by paediatricians and family physicians in Canada

| Oral health training | Paediatricians (n=237) | Family physicians (n=300) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Received training in … (%) | |||

| Medical school | 18.2 | 37.7 | <0.001* |

| Residency | 20.3 | 11.1 | 0.003* |

| Practice experience | 49.2 | 43.8 | 0.216* |

| Journals and CME | 29.7 | 15.8 | <0.001* |

| Oral health pamphlets | 13.6 | 10.4 | 0.268* |

| Hours of training in medical school or residency (%) | |||

| None | 17.9 | 22.3 | |

| Less than 1 h | 23.9 | 30.7 | 0.036* |

| 1 h to 3 h | 37.2 | 35.5 | |

| More than 3 h to 6 h | 11.1 | 7.3 | |

| More than 6 h | 9.9 | 4.2 | |

| Quality of training (%) | |||

| Did not receive any training or cannot recall | 40.2 | 49.0 | 0.001* |

| Poor to fair | 45.8 | 45.6 | |

| Good to excellent | 14.0 | 5.4 | |

| No oral health CME course taken in the past five years | 47.0 | 74.0 | <0.001* |

| Mean number of hours among those who have taken oral health CME courses (SD) | 1.8 (4.1) | 0.8 (2.4) | 0.001† |

χ2 test;

Student’s t test. CME Continuing medical education

Perceived importance of the physician’s role and willingness to adopt oral health-promotion activities

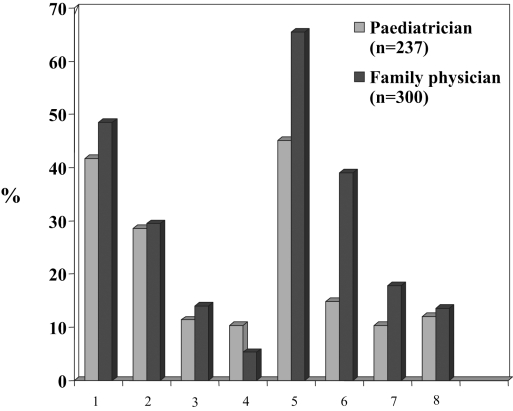

Seventy-nine per cent of paediatricians and 51% of family physicians considered their role in promoting the oral health of infants and toddlers as “very important”. When asked to rate their willingness to perform three oral health-promotion activities (on a five-point Likert scale from “least willing” to “most willing”), over 80% of the respondents were “most willing” to perform the following activities: lift the upper lip of infants and toddlers to check for tooth decay, advise parents or caregivers regarding preventive dental care aspects for their child, and refer suspected cases of ECC to dental health professionals. Reported barriers to performing these activities included, in decreasing frequency, respondents’ lack of dental knowledge, lack of time, lack of parental perceived need for dental care and parents’ lack of dental knowledge (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Perceived barriers for carrying out oral health-related activities reported by physicians surveyed: 1 = lack of clinical time; 2 = lack of parent’s or caregiver’s perceived need for dental care; 3 = lack of reimbursement for performing above-described activities; 4 = limited number of dental health professionals in the area for referral; 5 = lack of knowledge in identifying dental conditions; 6 = lack of knowledge of what parents should do to prevent or manage their child’s dental problems; 7 = belief that infants and toddlers are too young and uncooperative for this kind of oral examination; 8 = belief that dentists should perform these activities

Perceived need for oral health information

Eighty-five per cent of paediatricians and 92% of family physicians reported needing more information and resources on oral health topics. The most frequently requested topics were identifying ECC (86% of paediatricians and 92% of family physicians), dental caries preventive methods (79% of paediatricians and 88% of family physicians), and topical fluorides and fluoride supplements (69% of paediatricians and 75% of family physicians). The preferred methods for receiving information were through professional guidelines (51% of paediatricians and 42% of family physicians), CME courses (26% of paediatricians and 20% of family physicians) and information pamphlets (22% of paediatricians and 26% of family physicians).

Factors associated with carrying out oral health-related activities during well baby visits

After adjusting for the reported number of years in practice, physician type, practice location, number of well baby visits per month, number of ECC cases per month and percentage of the recent immigrant population seen as patients, paediatricians and family physicians who reported feeling confident in identifying dental caries and knowledgeable enough to discuss the topic and counsel parents were more likely to perform visual examinations of the teeth, counsel parents and assess the child’s risk for developing tooth decay (Table 6). Those who reported having received 3 h or more of oral health training during medical school or residency were nearly twice as likely to provide dental care counselling than were those who reported receiving less than 3 h. Similarly, those who reported having completed at least 1 h of CME courses in oral health topics in the past five years were nearly four times more likely to recommend a child’s first dental visit before one year of age.

TABLE 6.

Factors associated with physicians carrying out oral health-related activities during well baby visits

| Perform visual examination of teeth

|

Counsel on teething and dental care

|

Assess risk for developing tooth decay

|

Recommend first dental visit at younger than one year

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

| Oral health training during medical school and residency (more than 3 h versus less than 3 h) | 1.80 (0.95–3.42) | 1.92 (1.1–3.35) | 1.57 (0.89–2.78) | 2.04 (0.50–8.22) |

| Oral health CME courses taken in past five years (1 h or more versus none) | 1.27 (0.84–1.92) | 1.24 (0.84–1.83) | 1.01 (0.66–1.52) | 3.82 (1.16–12.6) |

| Knowledge scores (continuous; range 0 to 12; OR is per unit increase in knowledge scores) | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) | 1.00 (0.88–1.12) | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) |

| Feel confident in identifying dental caries in children (versus do not) | 3.60 (2.35–5.50) | 2.03 (1.38–2.98) | 2.55 (1.75–3.73) | 2.49 (0.76–8.17) |

| Feel knowledgeable enough to discuss and counsel parents regarding home dental care for children (versus do not) | 2.64 (1.78–3.92) | 6.24 (4.17–9.34) | 6.53 (4.04–10.5) | 3.68 (0.77–17.5) |

| Consider that physicians play a “very important” role in promoting oral health (versus do not) | 2.47 (1.64–3.71) | 3.70 (2.49–5.51) | 5.50 (3.47–8.73) | 0.47 (0.14–1.52) |

Odds ratio (OR) adjusted for number of years in practice, physician type, practice location, number of well baby visits per month, number of early childhood caries cases per month and proportion of recent immigrants seen as patients. CME Continuing medical education

DISCUSSION

The present study found that paediatricians and family physicians were knowledgeable about some aspects of ECC and infant oral health, but were uncertain identifying dental caries and the early signs of ECC. The majority of physicians reported that they play an important role and are involved in promoting the oral health of children in their practices; however, very few physicians reported recommending a first visit to the dentist before one year of age. Both groups of physicians reported receiving little training in oral health-related topics in medical school and residency. Those physicians who felt confident and received some form of training in medical school or residency were more likely to report including oral health-promotion activities.

A previous study by Lewis et al (24) reported that many respondents were unaware of the first signs of tooth decay, and Sanchez et al (23) reported that 83% of physicians performed oral examinations during children’s physical examinations; both of these results are similar to the ones found in the present study. However, fewer respondents in the present study reported examining the teeth and counselling parents compared with the study by Lewis et al (24).

Checklists, such as the Rourke Baby Record, endorsed by the CPS and the College of the Family Physicians of Canada recommend the first dental visit for children between two and three years of age (17,18). The findings of the present study are consistent with this recommendation; however, earlier visits – within six months of the first tooth’s eruption or before one year of age – are now recommended by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the Canadian Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and the Canadian Dental Association (27–29). Only 2.7% of respondents recommended the first dental visit within the first year, while in two other studies (21,24), 14% and 19% of paediatricians recommended the first preventive dental visit before six months of age . A recent survey (30) of American paediatricians and family physicians reported that only 19% of family physicians and 14% of paediatricians would recommend an early dental visit for a child with a low caries risk.

Similar to previous studies (21,23,24), paediatricians and family physicians in the present study reported receiving little training in oral health. Consistent with this finding, our respondents frequently requested more information and resources for the identification and prevention of dental disease in children. Lack of training and unfamiliarity with oral health issues may make it difficult for primary health care providers to assume a more active role in the oral health promotion of children. As suggested by the results of a randomized controlled trial of 118 North Carolina, USA, medical offices, this gap in knowledge may be addressed with CME. When providers were offered CME on screening for dental disease, the results indicated that nondental health professionals, once trained, would adopt these practices (31).

Most respondents perceived their role in promoting the oral health of infants and toddlers as being “very important”. Similar findings have been reported by Lewis et al (24) and others (21–23). While most respondents reported that they were willing to perform oral health-promotion activities, they also identified their lack of dental knowledge as a significant barrier to being more involved.

The present study had some limitations. Although the response rate in this study was similar to that in other physician surveys (32), nonrespondents may have different practices and experiences with respect to children’s oral health. However, a recent report (32) suggested that nonresponse bias may be of less concern in physician surveys than in surveys of the general public because physicians have more homogenous knowledge, training, attitudes and behaviours. Another limitation is the potential for ‘social desirability’ to bias respondent answers.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the present study suggest that physicians are knowledgeable about some aspects of ECC and infant oral health but not the identification of ECC. The majority of paediatricians and family physicians considered their role in children’s oral health as important and reported including certain aspects of oral health in well child visits. However, a reported lack of dental knowledge and training appeared to pose barriers, limiting physicians from playing a more active role.

Footnotes

SUPPORT: This study was supported by a Dental Faculty Research Fund from the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tinanoff N, O’Sullivan DM. Early childhood caries: Overview and recent findings. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brice DM, Blum JR, Steinberg BJ. The etiology, treatment, and prevention of nursing caries. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1996;17:92, 94, 96–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein P. Research recommendations: Pleas for enhanced research efforts to impact the epidemic of dental disease in infants. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02396.x. Erratum in 1996;56:128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Febres C, Echeverri EA, Keene HJ. Parental awareness, habits, and social factors and their relationship to baby bottle tooth decay. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:22–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broderick E, Mabry J, Robertson D, Thompson J. Baby bottle tooth decay in Native American children in Head Start centers. Public Health Rep. 1989;104:50–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruerd B, Jones C. Preventing baby bottle tooth decay: Eight-year results. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:63–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiboski CH, Gansky SA, Ramos-Gomez F, Ngo L, Isman R, Pollick HF. The association of early childhood caries and race/ethnicity among California preschool children. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03472.x. Erratum in 2003;63:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez JO, Eguren JC, Caceda J, Navia JM. The effect of nutritional status on the age distribution of dental caries in the primary teeth. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1564–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690090501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Caufield PW. The fidelity of initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants from their mothers. J Dent Res. 1995;74:681–5. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkowitz RJ, Jones P. Mouth-to-mouth transmission of the bacterium Streptococcus mutans between mother and child. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30:377–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milnes AR. Description and epidemiology of nursing caries. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbey P. MSc thesis. University of Toronto: Faculty of Dentistry; 1998. A case-control study to determine the risk factors, markers and determinants for the development of nursing caries. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence HP, Rogers JB, Romanetz M, Binguis S, Quequish T. Evaluation of the Sioux Lookout Zone prenatal nutrition program for prevention of early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2002;81(Special Issue A):A-385. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin SO, Gooch BF, Beltran E, Sutherland JN, Barsley R. Dental services, costs, and factors associated with hospitalization for Medicaid-eligible children, Louisiana 1996–97. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:21–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milnes AR, Rubin CW, Karpa M, Tate R. A retrospective analysis of the costs associated with the treatment of nursing caries in a remote Canadian aboriginal preschool population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:253–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglass JM, Douglass AB, Silk H. Infant oral health knowledge and training of medical health professionals. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:179. Abst. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panagiotou L, Rourke LL, Rourke JT, Wakefield JG, Winfield D. Evidence-based well-baby care. Part 1: Overview of the next generation of the Rourke Baby Record. Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:558–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2000;105:645–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gift HC, Milton B, Walsh V. Physician and caries prevention. Results of a physician survey on preventive dental services. JAMA. 1984;252:1447–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.11.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diu S, Gelbier S. Dental awareness and attitudes of general medical practitioners. Community Dent Health. 1987;4:437–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsamtsouris A, Gavris V. Survey of pediatrician’s attitudes towards pediatric dental health. J Pedod. 1990;14:152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulte JR, Druyan ME, Hagen JC. Early childhood tooth decay. Pediatric interventions. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1992;31:727–30. doi: 10.1177/000992289203101207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez OM, Childres NK, Fox L, Bradley E. Physicians’ views on pediatric preventive dental care. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:377–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis CW, Grossman DC, Domoto PK, Deyo RA. The role of the pediatrician in the oral health of children: A national survey. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E84. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce KM, Rozier RG, Vann WF., Jr Accuracy of pediatric primary care providers’ screening and referral for early childhood caries. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E82. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 149–93. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the Dental Home. < http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_DentalHome.pdf> (Version current at February 27, 2006)

- 28.Anonymous First visit to the dentist. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canadian Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Strategic planning session – meeting synopsis. Mirror Issues. 2004;23:16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ismail AI, Nainar SM, Sohn W. Children’s first dental visit: Attitudes and practices of US pediatricians and family physicians. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:425–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slade GD, Rozier RG, Zeldin LP, McKaig RG, Haupt K. Effect of continuing education on physicians’ provision of dental procedures. J Dent Res. 2004;83(Special Issue A):A1324. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:61–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]