SUMMARY

During Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis the primordial germ cell, P4, is generated via a series of unequal divisions. These divisions produce germline blastomeres (P1, P2, P3, P4) that differ from their somatic sisters in their size, fate and cytoplasmic content (e.g. germ granules). mes-1 mutant embryos display the striking phenotype of transformation of P4 into a muscle precursor, like its somatic sister. A loss of polarity in P2 and P3 cell-specific events underlies the Mes-1 phenotype. In mes-1 embryos, P2 and P3 undergo symmetric divisions and partition germ granules to both daughters. This paper shows that mes-1 encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase-like protein, though it lacks several residues conserved in all kinases and therefore is predicted not to have kinase activity. Immunolocalization analysis shows that MES-1 is present in four- to 24-cell embryos, where it is localized in a crescent at the junction between the germline cell and its neighboring gut cell. This is the region of P2 and P3 to which the spindle and P granules must move to ensure normal division asymmetry and cytoplasmic partitioning. Indeed, during early stages of mitosis in P2 and P3, one centrosome is positioned adjacent to the MES-1 crescent. Staining of isolated blastomeres demonstrated that MES-1 was present in the membrane of the germline blastomeres, consistent with a cell-autonomous function. Analysis of MES-1 distribution in various cell-fate and patterning mutants suggests that its localization is not dependent on the correct fate of either the germline or the gut blastomere but is dependent upon correct spatial organization of the embryo. Our results suggest that MES-1 directly positions the developing mitotic spindle and its associated P granules within P2 and P3, or provides an orientation signal for P2- and P3-specific events.

Keywords: C. elegans, MES-1, Germline, Asymmetric division, Mitotic spindle, P granules

INTRODUCTION

Asymmetric localization of cytoplasmic factors and unequal cell division are fundamental to the development of all eukaryotes. When these mechanisms are used to generate distinct daughter cells during development, the two events must be coordinately regulated, to ensure the proper segregation of factors to each daughter. This is observed in such diverse systems as bud formation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and neurogenesis in Drosophila (Madden and Snyder, 1998; Hawkins and Garriga, 1998; Jan and Jan, 2000; Schweisguth, 2000). As these events have become better understood, it has become apparent that many molecular components of cellular asymmetry are conserved (Drubin and Nelson, 1996; Shulman et al., 2000). Thus, elucidating new players and mechanisms for guiding asymmetric events can provide insights that extend beyond the system of study.

Early C. elegans embryos provide an ideal system in which to study asymmetry. These embryos undergo a series of stem-cell-like asymmetric divisions to establish the germline and somatic founder cells. The one-cell zygote, P0, divides to form a large somatic cell, AB, and a smaller germline cell, P1 (Deppe et al., 1978; Sulston et al., 1983). P1 and its daughter (P2) and granddaughter (P3) each divide asymmetrically to generate a somatic and a germline cell. The last of these divisions generates the primordial germ cell, P4. Besides the difference in size, the germline cells (P1, P2, P3, P4) differ from their somatic sisters in their fate, in the timing of their subsequent divisions and in their cytoplasmic content. The latter is strikingly illustrated by the presence of P granules, cytoplasmic structures that are specifically segregated to the germline cell at each division and that are required for fertility (Strome and Wood, 1982; Kawasaki et al., 1998).

Many of the components required for early C. elegans asymmetry have been elucidated. In the newly fertilized embryo, the sperm entry point specifies the posterior end (Goldstein and Hird, 1996). The sperm component(s) that accomplishes this has not yet been identified, but likely candidates are the centrosomes and their associated microtubules, which may cause cytoplasmic and cortical rearrangements that generate polarity in P0. The microfilament cytoskeleton is required for both correct P-granule segregation and unequal division in the one-cell embryo; embryos in which the microfilament cytoskeleton has been transiently disrupted divide symmetrically or with variable asymmetry and partition P granules to either P1 or AB or to both cells (Hill and Strome, 1988, 1990). A group of maternal-effect embryonic lethal genes, the par genes, plays crucial roles in establishment of anterior-posterior asymmetries in the early embryo (for review see Kemphues and Strome, 1997). Generally mutations in these genes result in symmetric and misoriented divisions, and P-granule mis-segregation. Consistent with their essential roles in establishing polarity, they encode cortical proteins that are asymmetrically distributed (Etemad-Moghadam and Kemphues, 1995; Guo and Kemphues, 1995; Boyd et al., 1996). This localization is controlled, at least in part, by nonmuscle myosin heavy chain, nmy-2 (Guo and Kemphues, 1996) and a novel transmembrane protein ooc-3 (Basham and Rose, 1999; Pichler et al., 2000). The nonmuscle myosin regulatory light chain gene, mlc-4, is also required for normal anterior-posterior polarity (Shelton et al., 1999).

The mes-1 gene also functions in asymmetric embryonic divisions, but specifically in the divisions of P2 and P3. First identified as a maternal-effect sterile mutant, mes-1 embryos produced from homozygous mothers lack the primordial germ cells, Z2 and Z3, and as a result develop into sterile adults (Capowski et al., 1991; Strome et al., 1995). Lineage analysis showed that in mes-1 mutant embryos, P4, the mother of Z2 and Z3, is transformed into a muscle precursor like its sister cell, D (Strome et al., 1995). Because of this transformation, mutant animals lack germ cells and contain extra muscle cells. Observation of mutant embryos by Nomarski analysis reveals that the transformation of P4 results from a loss of asymmetry in the division of both P2 and P3 (Strome et al., 1995). Each of these cells generates daughters more equal in size than in wild type, and both daughters frequently inherit P granules. Mis-segregated P granules are maintained in both daughters and their descendants, resulting in young larvae with P granules present in body wall muscle cells. This contrasts with wild-type embryos, in which occasionally mis-segregated P granules disappear from somatic cells, indicating that only germline cells are able to maintain P granules. The persistence of P granules in somatic cells of mes-1 mutants suggests that both daughters of P3 still retain some germline character, even after differentiating into muscle.

Analysis of fluorescently labelled P granules in living embryos has provided insights into cell-specific events in P2 and P3, and into the role of MES-1 in these events (Hird et al., 1996). The movement of the nucleus-centrosome complex and the segregation of P granules show a distinctive pattern in P2 and P3, which differs from the pattern in P0 and P1. In wild-type P0 and P1 cells, the centrosomes duplicate, separate, rotate 90° while attached to the nuclear envelope, and then form the mitotic spindle. This results in alignment of the spindle along the anterior-posterior axis in both cells. Concurrently but independent of the spindle and even of microtubules, P granules become partitioned to the posterior of the cell (Strome and Wood, 1983). In P2 and P3, P-granule segregation depends, at least in part, on the movement of the nucleus-centrosome complex (Fig. 1). P granules associate, in a perinuclear manner, with the nucleus-centrosome complex, and also disappear from the cytoplasm destined for the somatic daughter cell. It is unknown if this disappearance is due to degradation or disassembly of the granules. The nucleus-centrosome complex rotates and migrates to the ventral side of the P cell, and then forms the spindle. When the nuclear membrane breaks down, the associated P granules are released. Thus, in P2 and P3, rotation and migration of the nucleus-centrosome complex accomplishes three results: orientation of the spindle along the dorsal-ventral axis, asymmetric positioning of the spindle closer to the ventral pole and delivery of the majority of P granules to the ventral cytoplasm. These events ensure that P granules are delivered to the small, ventral (germline) daughter cell. These events in P2 and P3 are altered and uncoordinated in mes-1 mutant animals. The nucleus-centrosome complex does not migrate and P granules become segregated to one side instead of one pole of the spindle, resulting in their distribution to both daughter cells (Fig. 1). It is postulated that, in addition to P granules, other factors, such as muscle determinants, are also mislocalized; the presence of muscle determinants in both P4 and D causes both daughters to produce muscle.

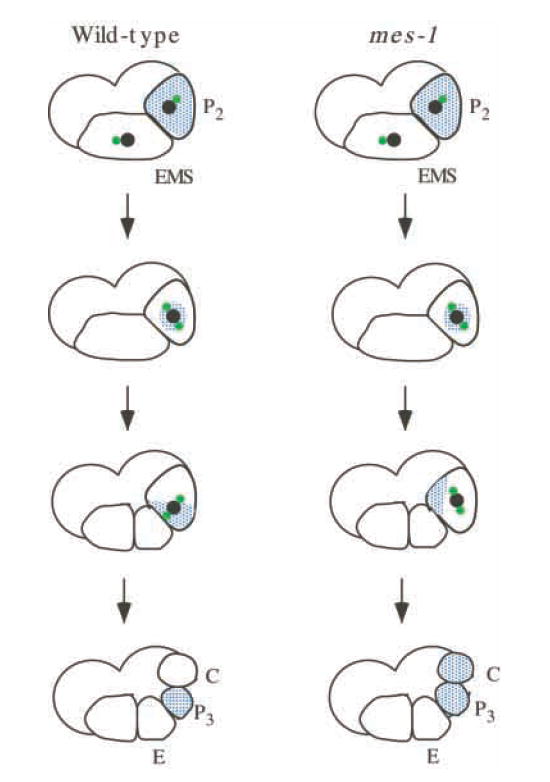

Fig. 1.

Division and P-granule partitioning in P2 in wild-type and mes-1 four-cell embryos. Nuclei are shown in black, centrosomes in green and P granules in blue. Anterior is towards the left and ventral is downwards. In wild-type embryos, the majority of P granules associate perinuclearly and the nucleus-centrosome complex rotates and migrates to the ventral side of P2, where P granules are deposited and the spindle forms. In mes-1 embryos P granules associate perinuclearly, but the nucleus-centrosome complex does not rotate and migrate. This results in a symmetrically placed spindle, which generally comes to lie along the correct axis. P granules are usually segregated to one side of the spindle and distributed to both daughters.

Here, we present molecular characterization of mes-1 and show that it encodes a transmembrane protein with similarity to receptor tyrosine kinases, though it is unlikely to have kinase activity. We also show that MES-1 is localized to a restricted portion of the cell membrane in the P cells of four- to 24-cell embryos. This pattern, on the P-cell membrane adjacent to its gut-cell neighbor, correlates with the location at which the next P cell forms. Thus, MES-1 localization is consistent with its role in the asymmetric divisions that generate P3 and P4. Analysis of its distribution in various cell-fate and patterning mutants suggests that the localization of MES-1 is not dependent on the correct fate of either the P cells or the gut cells, but is dependent upon correct spatial organization of the embryo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and alleles

Maintenance and genetic manipulation of C. elegans were carried out as described in Brenner (1974). C. elegans variety Bristol, strain N2 was used as the wild-type strain. The following mutations, polymorphisms, balancers and deficiencies were used in this study. LGI: glp-4(bn2ts), unc-13(e1091), mom-4(or39), hT1(I,V), pop-1(zu189), dpy-5(e61), hT2[bli-4(e937) let-?(h661)] (I,III), unc-101(m1), par-6(zu222), hIn1[unc-54(h1040)]. LGII: rol-1(e91), mex-1(zu121), mnC1[dpy-10(e128) unc-52(e444)]. LGIII: hT2[bli-4(e937) let-?(h661)] (I,III), pie-1(zu154), unc-25(e156), dpy-19(e1259), glp-1(q339), par-2(lw32), unc-45(e286ts), sC1[dpy-1(e1) let-?], lon-1(e185), par-3(it71), qC1[dpy-19(e1259ts) glp-1(q339)]. LGIV: hT1 (I,V), rol-4(sc8), par-1(b274), nT1(IV,V), DnT1[unc(n754)let] (IV,V), unc-5(e152), unc-22(s7), let-99(s1201), unc-31(e169). LGV: dpy-11(e1180), mom-2(or42), nT1(IV,V), him-5(e1490), DnT1[unc(n754)let] (IV,V), par-4(it75ts). LGX: mes-1(bn74ts), mes-1(bn7ts). mom-4, mom-2, let-99, pop-1 and pie-1 strains were from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. Strains containing par mutations were a gift from K. Kemphues; mex-1 was a gift from G. Seydoux; and pos-1 was a gift from J. Priess.

Cloning mes-1

mes-1 was mapped to cosmid C38D5, as described in Browning et al. (1996). Restriction fragments of C38D5 were cloned into pBS-Bluescript (Stratagene) using standard methods. Cosmid DNA and plasmids carrying cosmid fragments were prepared by standard alkaline lysis method (Sambrook et al., 1989) followed by RNase treatment and proteinase treatment. Each DNA (1-10 mg/ml) was coinjected with pRF4 (100 μg/ml), a plasmid carrying the dominant marker, rol-6(su1006), into the gonad arms of mes-1(bn7) homozygous hermaphrodites, using the procedure of Mello et al. (1991). Heritable lines of Rol transformants were obtained and examined for rescue of the Mes-1 phenotype. C38D5 and a 17-kb XhoI/NotI fragment of it rescued. A plasmid carrying this fragment was labelled with [α-32P] dCTP using Boehringer Mannheim’s Random Primed Labelling Kit and used as a probe to screen a λZAP mixed-stage C. elegans cDNA library (Barstead and Waterston, 1989). Thirty-two cDNAs were detected and found to correspond to eight different genes. Four of the cDNA groups crossreacted to C38D5 by virtue of repetitive sequences and did not actually map to the genomic region covered by C38D5. Antisense or sense RNA to the remaining cDNA groups was prepared essentially as described by Guo and Kemphues (1995), except that the MEGAscript In Vitro Transcription Kit by Ambion was used. The RNA (approx. 1 mg/ml) was injected into the gonad arms of wild-type hermaphrodites, and the progeny of injected worms were examined for sterility. RNA from one of the four cDNA groups resulted in a Mes-1 phenocopy.

Sequence analysis and 5′ end isolation

cDNAs were initially sequenced using Sanger dideoxy-mediated chain termination (Sambrook et al., 1989). Additional sequencing was performed as described in Holdeman et al. (1998). The 5′ end was isolated by RT-PCR. First-strand cDNA synthesis used an oligonucleotide primer that corresponded to the 5′ end of the longest isolated partial cDNA. PCR on first-strand RT reaction products used a 5′ oligonucleotide that corresponded to the predicted 5′ end and an internal 3′ primer. The DNA fragment was cloned into pBS-Bluescript (Stratagene) and sequenced. The 5′ end was confirmed by repeating the PCR using an oligonucleotide that hybridized to spliced-leader (SL1) sequence for the 5′ primer (Spieth et al., 1993).

For sequencing the mes-1 alleles, genomic DNA was prepared from homozygous mutant worms carrying each of the eight mutant alleles. The mes-1 gene was amplified using PCR as five segments that covered the entire coding region, some introns and all intron-exon boundaries. Each segment was cycle sequenced using ABI Prism Big Dye Cycle Sequencing (PE Applied Biosystems).

Northern analysis

Northern hybridization analysis was performed as described in Holdeman et al. (1998), using the rpp-1 transcript, which encodes a ribosomal protein, as a loading control (Evans et al., 1997). The intensity of the transcript bands was determined either from a scanned autoradiograph using NIH Image software or using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. The relative levels were expressed as a ratio of the mes-1 signal intensity to the intensity of the rpp-1 signal.

Antibody production

A bacterial 6×His fusion expression construct was made by cloning a 1418 base pair fragment, corresponding to intracellular amino acids 495-966, into the SacI and HindIII sites of the pET-28a vector (Novagen). This fragment was generated by PCR of the original cDNA isolate using oligonucleotides containing a SacI site (5′ primer) and a HindIII site (3′ primer). The fusion protein was expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) and purified using Ni-NTA agarose columns (Qiagen). The purified protein, isolated in a polyacrylamide gel slice, was injected into rats with Freunds adjuvant. Anti-MES-1 antibodies were purified from crude antiserum by blot affinity purification and elution by 0.2 M glycine, pH 2.8 (Olmsted, 1986). Following dialysis against PBS, the antibodies were passed over a column of 6×His-MES-6 (Korf et al., 1998) attached to AFFI-GEL active ester agarose 10 (Biorad) to remove nonspecific and denatured antibody. Anti-MES-1 antibodies were not able to detect MES-1 on a western blot from total embryo extract, but were able to detect MES-1 if immunoprecipitation was performed first.

Immunofluorescence analysis

To visualize MES-1 localization, animals were cut in a drop of M9 and fixed in cold methanol followed by cold acetone as described in Strome and Wood (1983). Samples were blocked in PBS, 1.5% bovine serum albumin, 1.5% non-fat dried milk prior to applying a 1:3 dilution of affinity-purified anti-MES-1 antibodies. Crude rabbit anti-PGL-1 antiserum (Kawasaki et al., 1998) diluted 1:30,000, rabbit anti-penta-acetyl-histone H4 (kindly provided by D. Allis; Lin et al., 1989) diluted 1:6000, and rabbit anti-actin (against C-terminal peptide, Sigma) diluted 1:250, were also used. Serum from one animal used to produce anti-MES-1 antibodies contains anti-centrosome antibodies as well as anti-MES-1 antibodies. The centrosomal staining is unrelated to MES-1, since it is still detectable in bn74 worms (a complete deletion allele of mes-1). Secondary antibodies used were affinity-purified fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rat, rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, Cy5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson) or Alexa 488 goat anti-rat (Molecular Probes), diluted 1:250. Samples were mounted in Vectashield anti-fade mounting media (Vector Laboratories). In one series of staining, ethidium bromide was included in the mounting medium to detect DNA.

Blastomere isolation

Blastomeres were isolated as described by Shelton et al. (1996), with modifications suggested by A. Skop (personal communication). Briefly, wild-type worms were cut in a drop of M9. The eggshell of young embryos (one-, two- and four-cell stages) was removed with hypochlorite (5-6% stock solution, diluted 1:6) treatment. Embryos were washed in egg salt buffer and the eggshell was further digested away in 5 U/ml chitinase, 20 mg/ml chymotrypsin in egg salt buffer for 7 minutes. Embryos were washed in three droplets of simplified growth medium (SGM) supplemented with 35% heat-treated calf serum. The vitelline membrane was removed by pipetting the embryos repeatedly through a narrow-bore drawn glass capillary. Cells were washed in serum-free SGM and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. The cells were then affixed to GCP-coated slides (0.2% gelatin, 0.002% chrome alum, 1 mg/ml polylysine) and stained with antibodies as described in the above section.

RESULTS

MES-1 is partially similar to receptor tyrosine kinases

To investigate how MES-1 participates in the asymmetric divisions of P2 and P3, we analyzed the gene. The mes-1 gene is located in the egl-15-sma-5 interval on LGX. Because there were few useful genetic markers for recombination mapping in this interval, macrorestriction analysis was used to search for allele-associated restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) (Browning et al., 1996). This analysis used infrequently cutting restriction enzymes and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to examine large fragments of DNA. DNA from two alleles of mes-1 showed an RFLP that mapped to cosmid C38D5 (Browning et al., 1996; data not shown). In DNA transformation rescue tests, the Mes-1 phenotype was rescued by the C38D5 cosmid, as well as by a 17 kb fragment of C38D5. This fragment was used to screen a cDNA library (Barstead and Waterston, 1989), and four different cDNAs that mapped to C38D5 were identified. It has been found that RNA prepared from cloned genes, when injected into wild-type hermaphrodites, produces a gene-specific phenocopy (Guo and Kemphues, 1995; Rocheleau et al., 1997; Fire et al., 1998). This phenomenon, termed RNA interference (RNAi), was used to determine which of the four cDNAs from C38D5 corresponded to mes-1. Injection of RNA from one cDNA phenocopied the Mes-1 defects. This cDNA was confirmed as mes-1 by failure to detect a transcript in northern analysis of mRNA from a deletion allele of mes-1 and by sequencing mutant alleles (see below).

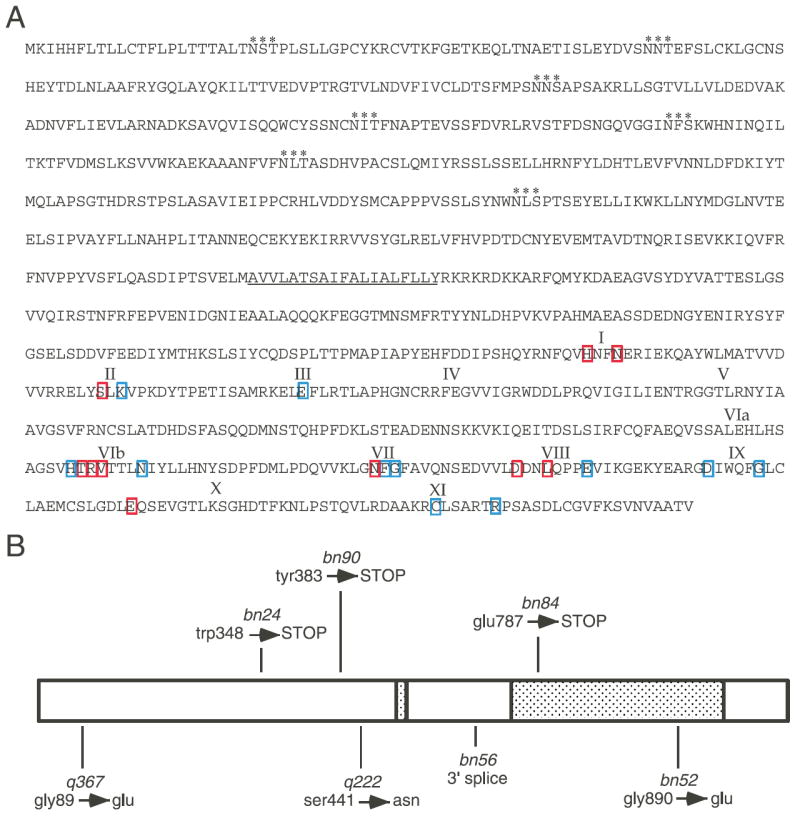

The nucleotide sequence of the mes-1 cDNA (Accession number AF200199, listed in GenBank under reference cosmid F54F7, Accession number Z67755, which extensively overlaps with cosmid C38D5) predicts that mes-1 encodes a protein of 966 amino acids (Fig. 2A) that shows overall structural similarity to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs; for review, see Hanks and Quinn, 1991; Van Der Greer et al., 1994). RTKs are a very large, well conserved family of proteins that are involved in signaling pathways for cell growth and differentiation. Consistent with it belonging in this class of proteins, MES-1 contains a signal sequence, a single transmembrane domain, and an intracellular kinase-like domain. The extracellular region of MES-1 contains seven potential glycosylation sites (consensus NXS/T where X is any amino acid except P and D) but no recognizable domains or motifs. The kinase region of RTKs consists of 11 subdomains, called I-XI, that have the following functions: I-III bind the phosphate donor Mg+2/ATP; IV is structural; V-VII are catalytic; VIII-IX provide substrate recognition; X and XI are undefined. The predicted MES-1 protein lacks any significant sequence similarity to subdomains I and II, and its subdomains III-XI show only 20-25% identity with other RTKs, compared with >35% identity for typical kinases. Furthermore, even within these subdomains, several amino acids required for catalytic activity are absent from MES-1 (Fig. 2A). Specifically, MES-1 has changes in 10 of the 21 invariant and nearly invariant amino acids that are found in almost all kinases, including serine/threonine kinases (Hanks and Quinn, 1991). The lack of a recognizable nucleotide binding site and the above described sequence differences within the kinase region suggest that MES-1 is not a functional kinase.

Fig. 2.

MES-1 protein sequence and allele mutations. (A) Predicted MES-1 amino acid sequence. Potential glycosylation sites are marked with asterisks (consensus NXS/T) and the transmembrane domain is underlined. Roman numerals show the approximate locations of kinase subdomains described in the text. Amino acids that are invariant or nearly invariant in RTKs are boxed. Blue boxes indicate the residue is conserved in MES-1 and red boxes indicate the residue is not conserved. (B) Schematic drawing of MES-1 showing the relative positions and amino acid changes for seven of the eight non-deletion alleles of mes-1. The shaded boxes represent the transmembrane and the kinase-like domains.

mes-1 alleles

Two alleles of mes-1 contain substantial alterations of the gene. bn74 has a 25 kb deletion that removes the entire coding region of mes-1 (Browning et al., 1996). bn89 is a more complex rearrangement consisting of both a deletion and a duplication: a 5.5 kb deletion removes the upstream region and 0.5-1 kb of coding sequence and a approx. 3 kb duplication contains much of the coding sequence. As expected, neither of these mes-1 alleles produces mRNA or protein (Figs 3A, 4D and data not shown).

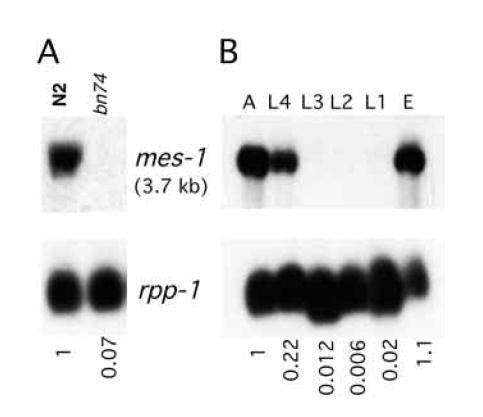

Fig. 3.

Northern analysis of mes-1 transcripts. (A) mes-1 mRNA is detectable in wild type (N2) and undetectable in the mes-1 deletion allele bn74. (B) mes-1 mRNA accumulation during development. PolyA+ RNA was isolated from wild-type hermaphrodites, which were synchronized at each of the six developmental stages shown. A, adults; E, embryos; L1-L4, four larval stages. In (A) and (B) a 2.6 kb partial cDNA clone of mes-1 was used as a probe to detect the 3.7 kb transcript. The transcript of the ribosomal gene, rpp-1, was used as a loading control. Relative levels of the mes-1 transcript are shown at the bottom.

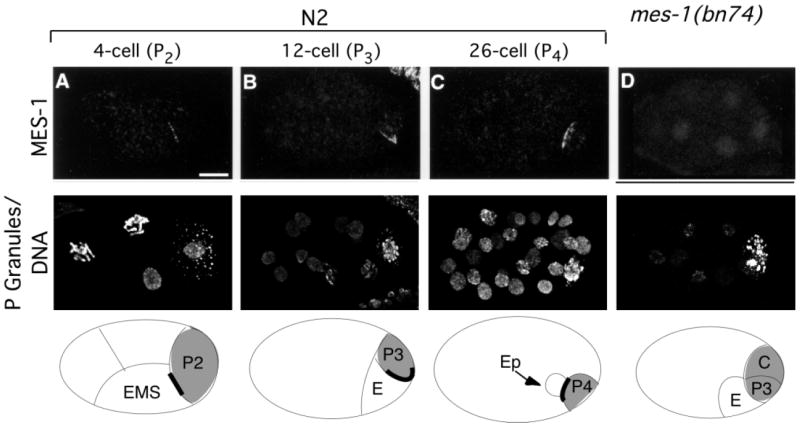

Fig. 4.

MES-1 localization in wild-type and mes-1 mutant embryos. Projections of multiple confocal optical sections. Anterior is towards the left and ventral is downwards. Top row stained with anti-MES-1 antibodies. Middle row stained with anti-PGL-1 and anti-acetyl-histone H4, which detect P granules and DNA, respectively. Bottom row shows schematic drawings of the embryos, with the germline and the gut cells indicated. Cells containing P granules are shaded gray, and the MES-1 crescent is shown as a thick black line. Delineation of the cells is only approximate and is based on the positions of the nuclei. Wild-type (N2) embryos at the four-cell stage (A), 12-cell stage (B) and 26-cell stage (C). MES-1 is localized as a crescent between the germline and the gut cells, specifically between P2 and EMS (A), P3 and E (B), and P4 and Ep (C). (D) bn74, a complete deletion of the mes-1 gene, lacks detectable MES-1 staining; eight-cell stage embryo shown. Scale bar: 10 μm.

The other eight alleles of mes-1 produce mRNA and were sequenced to determine their molecular lesions (Fig. 2B). The entire coding region and all intron-exon boundaries were sequenced. For one allele, bn7, no changes were found. Three alleles, bn24, bn90 and bn84, contain base pair changes that result in a premature stop codon. Allele bn56 contains a change in a 3′ splice site. Two alleles, q367 and q222, contain missense amino acid changes. Allele bn52 contains two mutations: a 50 bp deletion within intron 1 and a missense change of Gly890 to Glu in subdomain IX (Fig. 2B). RTKs have an invariant serine at that position. Only allele bn52 produces detectable embryo staining (data not shown). The distribution of MES-1 in bn52 is the same as in wild type, but the protein does not persist as long. Interestingly, all ten mes-1 alleles result in equally severe phenotypes.

mes-1 transcript is enriched in adults and embryos

The mes-1 gene produces a 3.7 kb transcript, which is first detected at the L4 stage, accumulates in adults, and is present in embryos (Fig. 3B). To investigate if the mes-1 transcript is germline specific, northern analysis was performed using RNA from glp-4(bn2) worms, which essentially lack germ cells (Beanan and Strome, 1992). The mes-1 transcript level in adult glp-4(bn2) worms is 20-30% of the wild-type adult level (data not shown). The enrichment of mes-1 in the germline of worms and its presence in embryos are consistent with the known function of mes-1 in early embryos. The presence of significant levels of mes-1 RNA in somatic cells (i.e. in glp-4 worms) was unexpected since mes-1 mutants display a strictly maternal-effect sterile phenotype. No specific pattern of MES-1 staining was detected in somatic tissues when wild-type animals were compared with bn74 animals.

MES-1 is localized in four- to 24-cell embryos at the junction between the germline cell and the gut cell

To address when and where MES-1 protein functions, its subcellular localization was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Rat antisera were raised against a 6×His-tagged fusion protein containing the 475 amino acid intracellular domain of MES-1 and were then affinity purified. The specificity of the antibody was confirmed by the fact that MES-1 staining was undetectable in worms homozygous for a deletion allele of mes-1, which removes the entire gene (allele bn74; Fig. 4D). MES-1 is detected as a thin crescent, initially in four-cell embryos between P2 and EMS and then in eight- to 12-cell embryos between P3 and E (Fig. 4A,B). The EMS blastomere gives rise to E, which produces gut (intestine), and MS, which produces pharynx and muscle (Deppe et al., 1978; Sulston et al., 1983). In this paper we refer to EMS as a gut cell, though it generates more than just gut. MES-1 persists through the formation of P4 at the 24-cell stage (Fig. 4C). After P4 is generated, MES-1 begins to fade and is usually not detectable beyond the 30-40-cell stage (data not shown).

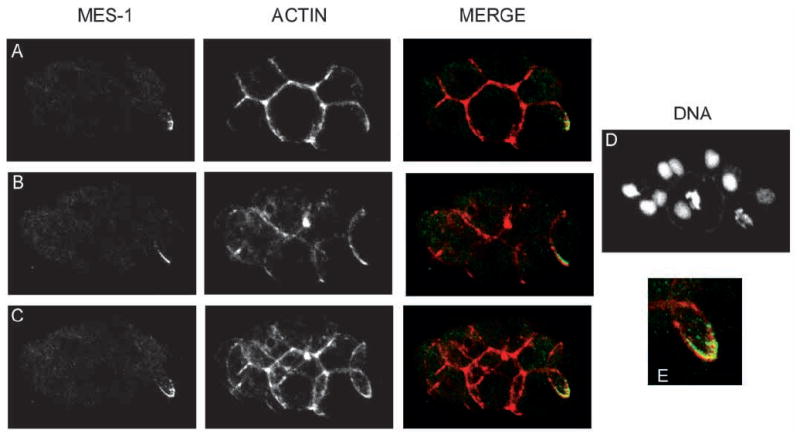

MES-1 is predicted to span the membrane. To confirm that MES-1 was located at the cell periphery, embryos were co-stained with an antibody to actin, which is concentrated in the cell cortex (Fig. 5A-E). Where MES-1 staining was present, it was adjacent to and sometimes overlapped with actin staining. The crescent shape of MES-1 staining outlined a portion of the contact area between the germline and the gut cell; the tips of the crescent point dorsally, towards the interior of the embryo.

Fig. 5.

MES-1 and actin localization in a wild-type 15-cell embryo. Projections of multiple confocal optical sections. Anterior is leftwards and ventral is downwards. Left column is anti-MES-1 staining. Middle column is anti-actin staining. Right column contains merged images. Red shows actin, green shows MES-1. MES-1 is localized at the cell periphery. (A) Projection of upper sections showing half the crescent. (B) Projection of lower sections showing the other half of the crescent. (C) Projections of all confocal sections. These sections show that one half of the crescent is on the left side of the embryo, and the other on the right, and that the tips of the crescent are pointed dorsally. (D) DNA stained with ethidium bromide. (E) Enlargement of the merged MES-1 crescent and actin.

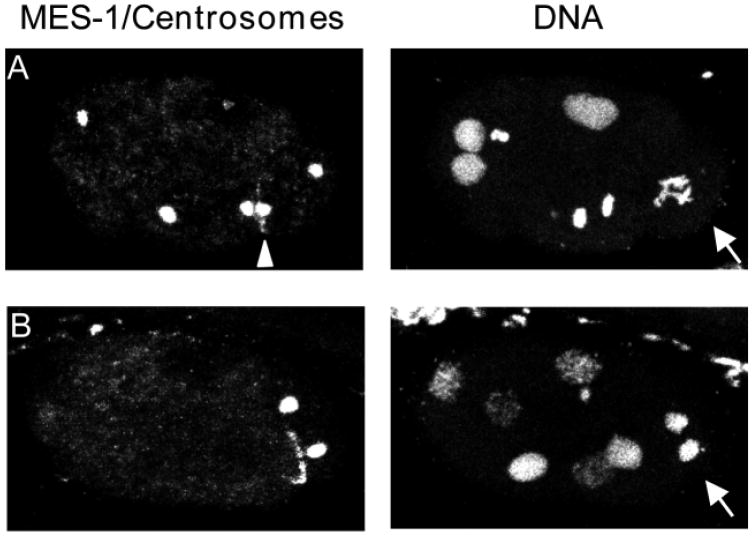

MES-1 localization appears to correlate with the position to which the nucleus-centrosome complex migrates (Hird et al., 1996). To determine the relative positions of MES-1 and the spindle, embryos were stained with antibodies that detect centrosomes (Fig. 6A-B). From late prophase through anaphase, the more ventral centrosome was closely juxtaposed to the MES-1 crescent, with the two appearing to almost touch (Fig. 6A). By telophase, MES-1 and the centrosome had separated (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

MES-1 and centrosome localization in wild-type six- to seven-cell embryos. Left panels show staining with antibodies to MES-1 and centrosomes. Right panels show staining of DNA with ethidium bromide. Projections of multiple confocal optical sections. Anterior is leftwards and ventral is downwards. Arrows point to P2 cell in (A) pro-metaphase and (B) telophase of mitosis. Arrowhead in (A) points to MES-1 crescent ‘sandwiched’ between posterior centrosome of EMS (left of MES-1) and ventral centrosome of P2 (right of MES-1).

The pattern of MES-1 staining is consistent with its function in the asymmetric divisions of P2 and P3. The stages that exhibit MES-1 localization temporally correlate with the P2/P3-specific role for MES-1. The loss of MES-1 after the formation of P4 reinforces the idea that MES-1 is only needed until this cell is formed. Its localization between the P cell and the gut cell also spatially correlates with where the future P cell will form (Hird et al., 1996).

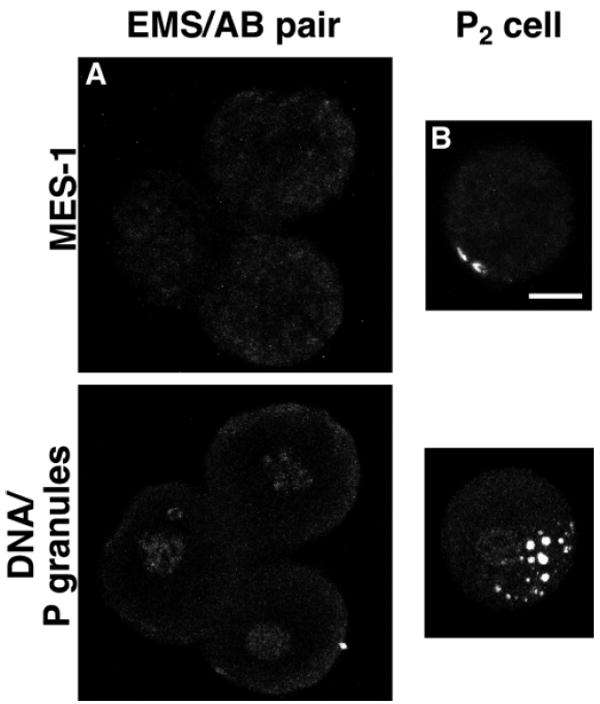

MES-1 is localized in the germline cell starting with P2

As a consequence of the localization of MES-1 to the area of contact between P2 and EMS and between P3 and E, it was not apparent from examining intact embryos whether the P cell or the gut cell or both contained protein. To address this issue, the P2 cell was dissociated from four-cell embryos and both it and the remaining embryo portion were fixed and stained for MES-1 (Fig. 7). MES-1 was detected on the surface of P2 and not on any other cells of the remaining embryo, most notably not on the EMS cell. Within the isolated P2 cell, the distribution of MES-1 was still in a crescent shape. Given the restriction of MES-1 to the P2 cell at the four-cell stage, it is reasonable to assume that in later-stage embryos MES-1 is present on the surface of P3 and P4, although this was not tested by staining isolated P3 and P4 cells. Consistent with this assumption, co-staining of MES-1 and actin (see Fig. 5) shows the cytoplasmic domain of MES-1 to be on the P-cell side of the zone of germline-gut contact. These immunostaining patterns suggest that MES-1 functions cell autonomously within the P cell.

Fig. 7.

MES-1 localization in isolated blastomeres. Projections of multiple confocal optical sections of an isolated germline blastomere and a partial embryo missing the germline blastomere. Top panels stained with anti-MES-1 antibodies. Bottom panels stained with anti-PGL-1 and anti-acetyl-histone H4, which detect P granules and DNA, respectively. (A) Remaining cells, ABa, ABp and EMS, of a four-cell embryo after removal of P2 (n=5) . (B) Isolated P2 from a four-cell embryo. This demonstrates the presence of MES-1 on P2 (n=6). In intact embryos P granules are located close to, but not centered over, the MES-1 crescent, so in the isolated P2 blastomere P-granule localization appears relatively normal. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Effects of cell fate and polarity defects on MES-1 localization

The distinct localization of MES-1, on P2 and P3 at the border with the gut cell, raised several questions, which were addressed by staining various early embryonic mutants for MES-1.

First, is the germline fate of the P cells required for MES-1 expression and localization? In pie-1 mutants P2 develops like its somatic sister, EMS (Mello et al., 1992). PIE-1 represses transcription of somatically expressed genes in the P cells, and the loss of this repression in pie-1 mutants causes the fate transformation of P2 (Seydoux et al., 1996). MES-1 localization appeared wild-type in pie-1 mutant embryos (data not shown). This suggests that P2 can lose at least one germline trait (transcriptional repression) and need not manifest a germline fate to properly express and localize MES-1.

Second, is the gut fate of EMS required for correct MES-1 patterning? In pop-1 embryos, EMS produces two E cells instead of an E and an MS cell (Lin et al., 1995). In mom-2 and mom-4 embryos, EMS produces two MS cells (Thorpe et al., 1997; Rocheleau et al., 1997). MES-1 localization appeared to be the same as in wild type in these mutant embryos (data not shown), suggesting that proper MES-1 localization is not dependent on the correct specification or fate of the EMS lineage.

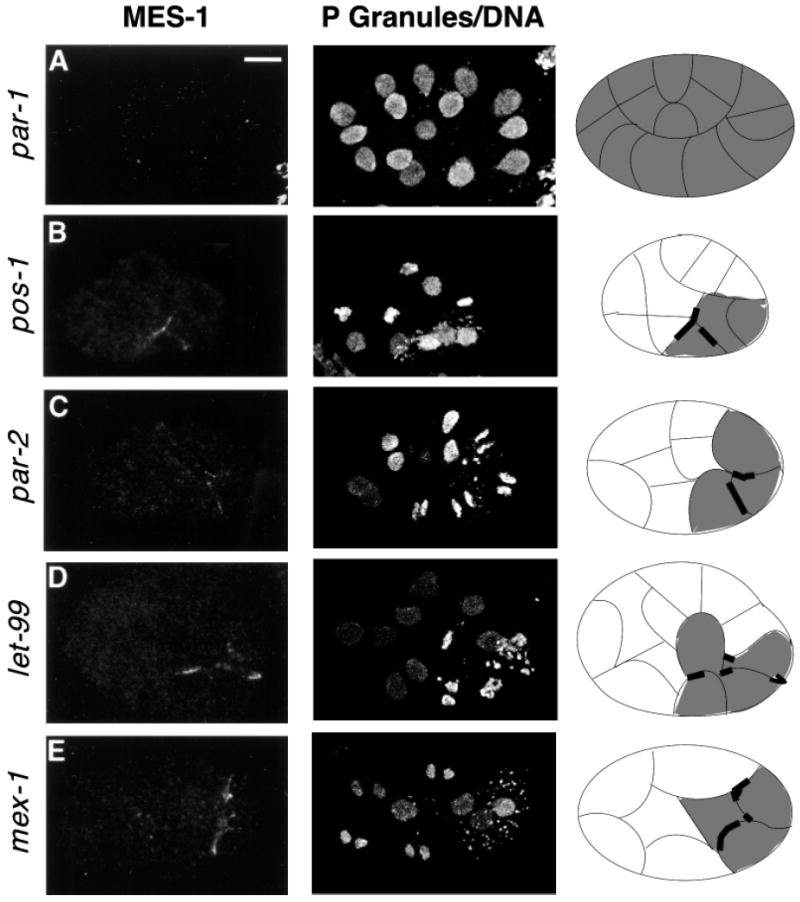

Last, do factors that regulate establishment of polarity and unequal divisions in one- and two-cell embryos affect the distribution of MES-1 in four-cell and later stages? Mutants used in this analysis exhibited MES-1 staining patterns that fell into two general categories.

The first category is a lack of detectable MES-1. This pattern was seen in mutant embryos from par-1, par-3 and par-4 animals. par-1 embryos undergo a symmetric first division and distribute P granules to both daughter cells (Kemphues et al., 1988). par-4 embryos show fairly normal first division asymmetry, but like par-1 distribute P granules to both daughter cells. par-3 embryos undergo a symmetric first division and sometimes distribute P granules to both daughters. MES-1 was not detectable in embryos from any of these par mutants (Fig. 8A and data not shown).

Fig. 8.

MES-1 localization in embryonic mutants that affect cellular polarity. Projections of multiple confocal optical sections. Anterior is leftwards and ventral is downwards. Left column stained with anti-MES-1 antibodies. Middle column stained with anti-PGL-1 and anti-acetyl-histone H4, which detect P granules and DNA, respectively. Right column shows schematic drawings of the embryos. Cells containing P granules are shaded gray and MES-1 is shown as a thick black line. Delineation of the cells is only approximate and is based on the positions of the nuclei. All embryos are at the 11- to 16-cell stage, which contains the germline cell P3. (A) par-1 embryo, which has no detectable MES-1. (B) pos-1 embryo showing the predominant MES-1 pattern of ectopic localization. (C) par-2, (D) let-99 and (E) mex-1 embryos, showing ectopic distribution of MES-1. Scale bar: 10 μm.

The second category displays a variety of MES-1 staining patterns which include ‘wild-type’, ‘ectopic’ and absent. Classification of the type of MES-1 staining was based on the following criteria: ‘wild-type’ – the MES-1 crescent was asymmetrically distributed on one side of a posteriorly located cell that contained P granules, but the embryo itself did not always appear to be the same as wild type; ‘ectopic’ – a MES-1 crescent was present on more than one face of a single cell or on more than one cell or on a cell that was not at the posterior end of the embryo. Mutants that produce a variable MES-1 pattern are pos-1, par-2, par-6, let-99 and mex-1 (Table 1 and Fig. 8B-E). pos-1 embryos display several defects, including symmetric division of P2 and P3 and distribution of P granules to both daughters of P3 (Tabara et al., 1999), which we speculate may result from an absence or altered distribution of MES-1. par-2 embryos correctly segregate P granules in the first division, but show an altered P1 division pattern and distribute P granules to both daughters of P1 (Kemphues et al., 1988; Boyd et al., 1996). Most par-6 embryos correctly segregate P granules in the first division, but in the four-cell stage, P granules are detected in all four blastomeres (Watts et al., 1996). In let-99 embryos spindles are not properly oriented, but nevertheless P granules are segregated properly in the first two divisions (Rose and Kemphues, 1998). In mex-1 embryos all founder lineages, including the germline, display cell-fate defects, suggesting that MEX-1 plays a role in general polarity of the embryo (Schnabel et al., 1996). mex-1 embryos often correctly segregate P granules during the division of P0 but then mis-segregate them in subsequent divisions (Mello et al., 1992). As stated above, all of these mutants display a variable, and often aberrant, distribution of MES-1 (Table 1). Together, these results indicate that MES-1 distribution depends, either directly or indirectly, on polarity cues established earlier in the embryo.

Table 1.

Percentage of mutant embryos displaying aberrant MES-1 localization

| Mutant strain | Type of aberrant MES stainingb | Cell stage of embryoa |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 | 4 | 6-7 | 8 | 10-14 | 15-20 | 21-28 | ||

| pos-1 (zu148) | Ect | 10c | 0 | 0 | 20 | 79 | 87 | 75 |

| mex-1 (zu121): 16°C | Ect | 20c | 20 | 11 | 25 | 74 | 89 | 71 |

| mex-1 (zu121): 25°C | Ect | 0 | 0 | 7 | 53 | 41 | 48 | 36 |

| par-2 (lw32) | Ect | 0 | 12 | 17 | 32 | 31 | 24 | 22 |

| Abs | 65 | 17 | 44 | 56 | 52 | 58 | ||

| let-99 (s1201) | Ect | 0 | 7 | 0 | 15 | 48 | 42 | 22 |

| Abs | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 17 | ||

| par-6 (zu222) | Ect | 0 | 50 | 50 | 78 | 71 | 74 | 50 |

| Abs | 11 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 33 | ||

For each stage a minimum of twenty embryos were counted.

Ect - ectopic MES-1 pattern Abs - absent or undetectable MES-1

Since MES-1 is not normally detected prior to the four-cell stage, the precocious staining is considered aberrant.

DISCUSSION

MES-1 is a predicted transmembrane protein that shows overall structural similarity to receptor tyrosine kinases, although it is unlikely to have kinase activity. MES-1 is at the surface of P2 and P3, which correlates both spatially and temporally with its role in the asymmetric divisions of these cells. Early embryonic mutants that alter embryonic polarity cause MES-1 to be ectopically localized or absent.

Function of MES-1 in asymmetric germline divisions

Based on the defects in migration of the nucleus-centrosome complex in mes-1 mutants and on the membrane localization of MES-1, we propose the following two models for how it may function. MES-1 may directly cause the movement of the nucleus-centrosome complex and its associated P granules in P2 and P3. In this model, MES-1 probably interacts with microtubules emanating from the centrosomes; MES-1 may bind microtubules directly or via a microtubule-associated protein or microtubule motor (for examples, see Thaler and Haimo, 1996; Stearns, 1997). MES-1, together with any associated proteins, pulls the nucleus-centrosome complex towards itself, resulting in proper alignment and asymmetric positioning of the spindle. The close physical proximity between the MES-1 crescent and one centrosome of the spindle seems to support this model. Alternatively, MES-1 could provide an orientation signal for events in P2 and P3. Its location may mark an area of the cell and signal where the next P cell is to be generated. The nucleus-centrosome complex and P granules would then respond to this signal and migrate towards it. These two models are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

MES-1 also participates in orienting a gradient of activity that stabilizes or destabilizes P granules. As described earlier, P granules not only aggregate perinuclearly, but they also disappear from the portion of the cell destined for the somatic daughter. This behavior is probably due to a gradient of P-granule stabilizing and/or destabilizing activity. In mes-1 mutant embryos, P granules disappear from the wrong region of the cell (see Fig. 1). As a result, P granules come to lie along one side, instead of one pole, of the spindle and consequently are partitioned to both daughter cells. The role of MES-1 in positioning the P-granule gradient, but not in forming the gradient, is analogous to that of Inscuteable in Drosophila neuroblasts. The determinant Numb is asymmetrically localized as a crescent and placement of the crescent, but not its formation, is dependent on Inscuteable (Kraut et al., 1996).

In formulating models for MES-1 function, the temperature-sensitivity of the Mes-1 phenotype needs to be considered. All ten alleles of mes-1, including a deletion of the entire coding sequence, exhibit a large percentage (70-90%) of sterile progeny at high temperature and a low percentage (10-15%) at lower temperature (Capowski et al., 1991). Indeed, division asymmetry in P2 and P3 are usually normal in mes-1 embryos at low temperature and altered at high temperature (Strome et al., 1995; E. Schierenberg and S. S., unpublished). This reveals that the process that controls unequal division and partitioning in P2 and P3 is inherently sensitive to temperature and does not absolutely require MES-1 at low temperature. Through an interaction or dimerization, MES-1 may stabilize a factor that is prone to inactivation at high temperature. Alternatively, there may be redundant pathways for achieving correct division of P2 and P3, one controlled by MES-1 and a separate one that is prone to inactivation at high temperature.

Possible mechanisms of MES-1 function

While MES-1 shows overall similarity to receptor tyrosine kinases, it lacks several subdomains and invariant amino acids that are required for kinase activity. Thus, it is probably not catalytically active. How then does MES-1 function?

MES-1 may acquire kinase activity through association with another kinase, either another RTK (e.g. Qian et al., 1992, 1994; Wada et al., 1990; Pinkas-Kramarski et al., 1996) or a non-receptor kinase. An associated kinase could either phosphorylate MES-1, creating docking sites (see below), or itself generate an intracellular signal to orient P2 and P3 events, as discussed above. An alternative scenario is that association of MES-1 with a kinase may instead have a dominant-negative effect and inhibit the activity of the kinase.

MES-1 may assemble into and function as part of a localized multi-component complex, similar to many kinases and phosphatases (Faux and Scott, 1996; Pawson and Scott, 1997). Indeed, MES-1 contains four potential binding sites for Srchomology-2 (SH2) domains. SH2 domains recognize phosphotyrosines in a short motif and mediate protein-protein interactions (Pawson, 1995). Budding in yeast provides a striking example of assembly and use of a localized complex to orient cell division. The bud site contains multiple proteins, including GTPases and Bni1, a scaffold protein that links the GTPases with the actin cytoskeleton (for review see Cabib et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1999). Localized reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton leads to reorientation of the mitotic spindle. A similar series of events may occur through MES-1 and an associated complex in P2 and P3.

If MES-1 is a receptor, what is the nature and source of its ligand? The observation that MES-1 is seen only on the surface of P2 and P3 where they contact the gut cell suggests that the gut cell supplies the ligand and that the ligand may be membrane-associated itself. MES-1 and its ligand may interact through direct cell-cell contacts, in a manner analogous to that of the Eph subfamily of RTKs and ephrin membrane-associated ligands (for review see Brüchner and Klein, 1998). Interaction with this hypothetical ligand may cause MES-1 to aggregate to only the portion of the P cell that contacts the gut cell, which may activate MES-1.

Do EMS and E signal division asymmetry in P2 and P3?

It has been thought that the asymmetric divisions of the germline cells occur cell autonomously. Isolated P2 and P3 cells did not reorient their spindles in response to contact with a gut blastomere, suggesting that germline-gut contact does not control those P-cell divisions (Goldstein, 1995). Additionally, posterior fragments of P2 extruded from the eggshell early after formation of P2 were able to divide unequally (Schierenberg, 1987). However, posterior fragments of P2 extruded later in the cell cycle did not divide asymmetrically (Schierenberg, 1987). This suggests that the cue for asymmetric division is repositioned away from the posterior during the course of the cell cycle. This is consistent with a model in which EMS signals P2, possibly through MES-1, to attract the cortical site that controls asymmetry to the ventral-anterior side of P2. Our findings that MES-1 appears only where P2 contacts EMS revive the possibility that EMS indeed signals P2. With knowledge of the timing of appearance and spatial restriction of MES-1, it is important to re-examine the question of whether the asymmetric divisions of P2 and P3 occur cell autonomously or are influenced by their EMS/E neighbor.

MES-1 localization is affected by defects in embryonic polarity and correlates with P granules

The aberrant pattern of MES-1 seen in mutant embryos with polarity defects suggests that MES-1 localization requires correct embryonic organization, which is not surprising. However, some results were unexpected, in particular observing that certain par mutants show normal patterns of MES-1 and observing that most mutants that show altered patterns of MES-1 at later stages show a wild-type pattern early on. There is a general correlation between the severity and stage of MES-1 mislocalization and the severity and stage of P-granule mis-segregation in the various mutants. par-1, par-3 and par-4 embryos generally mis-segregate P granules during the first division and lack detectable MES-1 staining, whereas par-2, let-99, pos-1 and mex-1 generally segregate P granules correctly during the first division and generally show a normal MES-1 distribution early and then defective distributions later. Early P-granule mis-segregation is probably indicative of severe disruption of polarity, which in turn is likely to impair the cytoskeletal or cortical system that mediates correct localization of MES-1.

A further correlation between MES-1 and P granules was observed in those mutants that displayed wild-type or ectopic MES-1 distributions. In wild-type embryos, the cells that have MES-1 on their surface (P2, P3 and P4) always contain P granules. Similarly, in mutant embryos, cells that appeared to have MES-1 on their surface were almost always observed to contain P granules. These observations are consistent with P-granule segregation being directed by MES-1 toward the region of the cell where it is located. However, the converse was not necessarily true: cells containing P granules did not always display MES-1 on their surface. The presence of P granules in cells that did not exhibit MES-1 may simply be the result of mis-segregation prior to the stages when MES-1 is present. The close physical association between MES-1 and one centrosome of the spindle observed in wild-type embryos was also observed in mutant embryos that exhibited ectopic MES-1. The correlation in these mutant embryos was not absolute, but this may be a consequence of our inability to assign which cell actually contains MES-1.

MES-1 may be needed to maintain germline-gut contact

Since P0 and P1 already have in place a mechanism for asymmetric divisions, why is a distinct P2/P3-specific mechanism needed? The answer probably relates to the phenomenon of polarity reversal and the hypothesis that germline cells need to be in contact with the gut for proper development. In wild-type embryos that have been released from the constraints of the eggshell, the P daughter of both P0 and P1 is formed to the posterior of its somatic sister. Then a switch occurs, termed polarity reversal, and the P daughter of both P2 and P3 is formed to the anterior of its somatic sister (Schierenberg, 1987). Had the divisions that produce the P cells to the posterior continued in P2 and P3, the germline cells P3 and P4 would have been separated from the gut. Thus, polarity reversal offers a mechanism to maintain contact between the germline and gut cells. Two observations suggest that MES-1 is involved in polarity reversal. First, it is localized in the proper place at the proper time to play a role. Second, mes-1 mutant embryos released from the constraints of the eggshell do not display polarity reversal (E. Schierenberg, personal communication).

Contact between the germline and gut is observed in many species. Embryos of the nematode Acrobeloides nanus (formally named Cephalobus sp.; Wiegner and Schierenberg, 1998) undergo the same P0 and P1 division patterns as C. elegans but then do not display a reversal of polarity during the divisions of P2 and P3 (Skiba and Schierenberg, 1992), resulting in all four P cells being formed to the posterior of their somatic sisters. This causes P3 and P4 to be separated from the gut cells. Intriguingly, just prior to gastrulation, cell migrations result in P4 becoming positioned next to E, thereby re-establishing contact between the germline and gut. Since MES-1 is proposed to function in polarity reversal in C. elegans, it is predicted that A. nanus, which lacks reversal, would either lack MES-1 or use it for another purpose. In many other species, such as Drosophila, Xenopus and mice, primordial germ cells associate with the hindgut (Wylie, 1999). These examples suggest that germline-gut contact is a common feature and is likely to be required for normal germline development.

An association between the gut and germ cells may guide germ-cell ingression during gastrulation. In C. elegans, the two gut cells (Ea and Ep) are the first cells to migrate inward during gastrulation. P4 follows them into the interior of the embryo (Sulston et al., 1983). P4 does not migrate inward in embryos in which migration of the two E cells has been inhibited (Schierenberg and Junkersdorf, 1992; Powell-Coffman et al., 1996). Similar events occur in Drosophila, where the primordial germ cells (PGCs) first travel passively to the hindgut during gastrulation and then actively migrate through the hindgut to the gonad (Jaglarz and Howard, 1994). Analysis of Drosophila PGC behavior in mutants that affect the gut suggests that the timing and direction of PGC migration out of the gut lumen depends upon developmental changes in the gut epithelium (Warrior, 1994; Jaglarz and Howard, 1995). Another role for the germline-gut contact in C. elegans is suggested by the observation of Sulston et al. (1983) that during late embryogenesis Z2 and Z3 project lobes into two cells of the gut, possibly receiving nourishment from this attachment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Coulson for cosmids; the Genome Sequencing Centers and John Speith for sequence information; Mark Parker for assistance with sequencing; Ahna Skop for advice on blastomere isolation; and John White, Kevin O’Connell, and Ahna Skop for helpful comments on the manuscript. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship GM14599 to L. A. B., NSF grant IBN-9630952 to S. S. and L. A. B., and NIH grant GM34059 to S. S.

References

- Barstead RJ, Waterston R. The basal component of the nematode dense-body is vinculin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10177–10185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basham SE, Rose LS. Mutations in ooc-5 and ooc-3 disrupt oocyte formation and the reestablishment of asymmetric PAR protein localization in two-cell Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Dev Biol. 1999;215:253–263. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beanan M, Strome S. Characterization of a germ-line proliferation mutation in C. elegans. Development. 1992;116:755–766. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.3.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd L, Guo S, Levitan D, Stinchcomb DT, Kemphues KJ. PAR-2 is asymmetrically distributed and promotes association of P granules and PAR-1 with the cortex in C. elegans embryos. Development. 1996;122:3075–3084. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning H, Berkowitz L, Madej C, Paulsen JE, Zolan ME, Strome S. Macrorestriction analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans genomic DNA. Genetics. 1996;144:609–619. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüchner K, Klein R. Signalling by Eph receptors and their ephrin ligands. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabib E, Drgonová J, Drgon T. Role of small G proteins in yeast cell polarization and wall biosynthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capowski E, Martin E, Garvin C, Strome S. Identification of grandchildless loci whose products are required for normal germ-line development in the nematode C. elegans. Genetics. 1991;129:1061–1072. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.4.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deppe U, Schierenberg E, Cole T, Krieg C, Schmitt D, Yoder B, van Ehrenstein G. Cell lineages of the embryo of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:376–380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drubin DG, Nelson WJ. Origins of cell polarity. Cell. 1996;84:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Asymmetrically distributed PAR-3 protein contributes to cell polarity and spindle alignment in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83:743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Zorio D, MacMorris M, Winter CE, Lea K, Blumenthal T. Operons and SL2 trans-splicing exist in nematodes outside the genus Caenorhabditis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9751–9756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faux MC, Scott JD. Molecular glue:kinase anchoring and scaffold proteins. Cell. 1996;85:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B. Cell contacts orient some cell division axes in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1071–1080. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Hird SN. Specification of the antero-posterior axis in C. elegans. Development. 1996;122:1467–1474. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative ser/thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Kemphues KJ. A non-muscle myosin required for embryonic polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1996;382:455–458. doi: 10.1038/382455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks SK, Quinn AM. Protein kinase catalytic domain sequence database: identification of conserved features of primary structure and classification of family members. In: Hunter T, Sefton BM, editors. Methods Enzymology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 38–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins N, Garriga G. Asymmetric cell division: from A to Z. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3625–3638. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DP, Strome S. An analysis of the role of microfilaments in the establishment and maintenance of asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans zygotes. Dev Biol. 1988;125:75–84. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D, Strome S. Brief cytochalasin-induced disruption of microfilaments during a critical interval in one-cell C. elegans embryos alters the partitioning of development instructions to the two-cell embryo. Development. 1990;108:159–172. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hird SN, Paulsen JE, Strome S. Segregation of P granules in living Caenorhabditis elegans embryos:cell-type-specific mechanisms for cytoplasmic localization. Development. 1996;122:1303–1312. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdeman R, Nehrt S, Strome S. MES-2, a maternal protein essential for viability of the germline in Caenorhabditis elegans, is homologous to a Drosophila Polycomb group protein. Development. 1998;125:2457–2467. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz MK, Howard KR. The active migration of Drosophila primordial germ cells. Development. 1994;121:3495–3503. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz MK, Howard KR. Primordial germ cell migration in Drosophila melanogaster is controlled by somatic tissue. Development. 1995;120:83–89. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan Y-N, Jan LY. Polarity in cell division: what frames thy fearful asymmetry? Cell. 2000;100:599–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki I, Shim Y-H, Kirchner J, Kaminker J, Wood WB, Strome S. PGL-1, a predicted RNA-binding component of germ granules, is essential for fertility in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;94:635–645. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemphues KJ, Priess JR, Morton DG, Cheng N. Identification of genes required for cytoplasmic localization in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1988;52:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemphues KJ, Strome S. Fertilization and establishment of polarity in the embryo. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C ELEGANS II. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 335–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I, Fan Y, Strome S. The Polycomb group in Caenorhabditis elegans and maternal control of germline development. Development. 1998;125:2469–2478. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Chia W, Jan LY, Jan YN, Knoblich JA. Role of inscuteable in orienting asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;383:50–55. doi: 10.1038/383050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Klee SK, Evangelista M, Boone C, Pellman D. Control of mitotic spindle position by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae formin Bni1p. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:947–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Leone JW, Cook RG, Allis CD. Antibodies specific to acetylated histones document the existence of deposition- and transcription-related histone acetylation in Tetrahymena. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1577–1588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Thompson S, Priess JR. pop-1 encodes an HMG box protein required for the specification of a mesoderm precursor in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83:599–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden K, Snyder M. Cell polarity and morphogenesis in budding yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:687–744. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Draper BW, Krause M, Weintraub H, Priess J. The pie-1 and mex-1 genes and maternal control of blastomere identity in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1992;70:163–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90542-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted JB. Analysis of cytoskeletal structures using blot-purified monospecific antibodies. In: Vallee RB, editor. Methods In Enzymology. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T. Protein modules and signaling networks. Nature. 1995;373:573–580. doi: 10.1038/373573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T, Scott JD. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler S, Gonczy P, Schnabel H, Pozniakowski A, Ashford A, Schnabel R, Hyman AA. ooc-3, a novel putative transmembrane protein required for establishment of cortical domains and spindle orientation in the P1 blastomere of C. elegans embryos. Development. 2000;127:2063–2073. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, Levkowitz G, Alroy I, Klapper L, Lavi S, Seger R, Ratzkin BJ, Sela M, Yarden Y. Diversification of Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signalling combinatorial receptor interactions. EMBO J. 1996;15:2452–2467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Coffman JA, Knight J, Wood WB. Onset of C. elegans gastrulation is blocked by inhibition of embryonic transcription with an RNA polymerase antisense RNA. Dev Biol. 1996;178:472–483. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Decker SJ, Greene MI. p185c-neu and epidermal growth factor receptor associate into a structure composed of activated kinases. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1330–1334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Levea CM, Freeman JK, Dougall WC, Greene MI. Heterodimerization of epidermal growth factor receptor and wild-type or kinase-deficient neu: a mechanism of interreceptor kinase activation and transphosphorylation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1500–1504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau CE, Downs WD, Lin R, Wittmann C, Bei Y, Cha Y-H, Ali M, Preiss J, Mello CC. Wnt signalling and an APC-related gene specify endoderm in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1997;90:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose LS, Kemphues K. The let-99 gene is required for proper spindle orientation during cleavage of the C. elegans embryo. Development. 1998;125:1337–1346. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.7.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook JE, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schierenberg E. Reversal of cellular polarity and early cell-cell interaction in the embryo of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1987;122:452–463. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierenberg E, Junkersdorf B. The role of eggshell and underlying vitelline membrane for normal pattern formation in the early C. elegans embryo. Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1992;202:17–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00364592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweisguth F. Cell polarity: fixing cell polarity with Pins. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R265–R267. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel R, Weigner C, Hutter H, Feichtinger R, Schnabel H. mex-1 and the general partitioning of cell fate in the early C. elegans embryo. Mech Dev. 1996;54:133–147. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux G, Mello CC, Pettitt J, Wood WB, Priess JR, Fire A. Repression of gene expression in the embryonic germ lineage of C. elegans. Nature. 1996;382:713–716. doi: 10.1038/382713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton CA, Bowerman B. Time-dependent responses to glp-1-mediated inductions in early C. elegans embryos. Development. 1996;122:2043–2050. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton CA, Carter JC, Ellis GC, Bowerman B. The nonmuscle myosin regulatory light chain gene mlc-4 is required for cytokinesis, anterior-posterior polarity, and body morphology during Caenohabditis elegans embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:439–451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman JM, Benton R, St Johnston D. The Drosophila homolog of C. elegans PAR-1 organizes the oocyte cytoskeleton and directs oskar mRNA localization to the posterior pole. Cell. 2000;101:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiba F, Schierenberg E. Cell lineages, developmental timing, and spatial pattern formation of free-living soil nematodes. Dev Biol. 1992;151:597–610. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90197-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieth J, Brooke G, Kuersten S, Lea K, Blumenthal T. Operons of C. elegans: polycistronic mRNA precursors are processed by trans-splicing of SL2 to downstream coding regions. Cell. 1993;73:521–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90139-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns T. Motoring to the finish:kinesin and dynein work together to orient the yeast mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:957–960. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Wood WB. Immunofluorescence visualization of germ-line-specific cytoplasmic granules in embryos, larvae, and adults of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1558–1562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.5.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Wood WB. Generation of asymmetry and segregation of germ-line granules in early Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Cell. 1983;35:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Martin P, Schierenberg E, Paulsen J. Transformation of the germ line into muscle in mes-1 mutant embryos of C. elegans. Development. 1995;121:2961–2972. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabara H, Hill RJ, Mello CC, Priess JR, Kohara Y. pos-1 encodes a cytoplasmic zinc-finger protein essential for germline specification in C. elegans. Development. 1999;126:1–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler CD, Haimo LT. Microtubules and microtubule motors: mechanisms of regulation. Int Rev Cytol. 1996;164:269–327. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe CJ, Schlesinger A, Carter JC, Bowerman B. Wnt signaling polarizes an early C. elegans blastomere to distinguish endoderm from mesoderm. Cell. 1997;90:695–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Greer P, Hunter T, Lindberg RA. Receptor protein-kinases and their signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:251–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Qian X, Greene MI. Intermolecular association of the p185neu proten and EGF receptor modulates EGF receptor function. Cell. 1990;61:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90697-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Boyd L, Draper BW, Mello CC, Priess JR, Kemphues KJ. par-6, a gene involved in the establishment of asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos, mediates the symmetric localization of PAR-3. Development. 1996;122:3133–3140. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrior R. Primordial germ cell migration and the assembly of the Drosophila embryonic gonad. Dev Biol. 1994;166:180–194. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegner O, Schrienberg S. Specification of gut cell fate differs significantly between the nematodes Acrobeloides nanus and Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1998;204:3–14. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie C. Germ cells. Cell. 1999;96:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]