Abstract

The authors assessed the relative impact of structural and social influence interventions on reducing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV risk behavior among female sex workers in the Philippines (N = 897). Four conditions included manager influence, peer influence, combined manager–peer influence, and control. Intervention effects were assessed at the establishment level in multilevel models because of statistical dependencies among women employed within the same establishments. Control group membership predicted greater perceived risk, less condom use, less HIV/AIDS knowledge, and more negative condom attitudes. Combination participants reported more positive condom attitudes, more establishment policies favoring condom use, and fewer STIs. Manager-only participants reported fewer STIs, lower condom attitudes, less knowledge, and higher perceived risk than peer-only participants. Because interventions were implemented at the city level, baseline and follow-up city differences were analyzed to rule out intervention effects due to preexisting differences.

Keywords: female commercial sex workers, HIV/AIDS risk, social influence intervention, STIs, condom use

Female commercial sex workers (FCSWs) are at high risk of transmitting HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). This is particularly true in Asian countries, such as the Philippines. For instance, a recent large survey showed an exceptionally high prevalence rate of chlamydiosis among Filipino FCSWs ranging from 27% to 36% (World Health Organization, 2002). According to the survey, the principal mode of transmission was heterosexual contact (World Health Organization, 2002). Because there is no vaccine or cure, HIV prevention depends on one’s ability to modify risky behaviors. With FCSWs, risk reduction typically means consistent and appropriate condom use. However, safe sex practices may be difficult to maintain when one’s livelihood depends on customers who expect or demand sex without a condom.

HIV prevention has traditionally focused on using cognitive–behavioral individually oriented approaches to induce beneficial changes in the individual’s attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors regarding HIV, with little attention to important structural–environmental factors that also account for individual behaviors (O’Leary, Holtgrave, Wright-DeAguero, & Malow, 2003). However, individualized prevention strategies may be less than optimal in changing risky behaviors in such situations as those of commercial sex workers (Bandura, 1982, 1987; Ford et al., 1996; O’Leary & Martins, 2000; Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1990). Social–structural factors, such as extreme poverty, which characterizes Filipino FCSWs, and a lack of support by employers as well as customers may impede safe sex practices; satisfying the customer’s desire for sex without a condom may have become almost mandatory in maintaining one’s livelihood and reducing conflicts with employers, despite the FCSW’s personal perception of risk. Peers may also exert an influence on safe sex behaviors when FCSWs are based within establishments. Therefore, economic factors, peer influences, and employment- or employer-related factors may have become a major barrier against consistent condom use (Morisky et al., 1998; Outwater et al., 2000).

In contrast, a perception of a supportive attitude by one’s employer toward condom use has had a direct influence on more condom use (Morisky, Stein, et al., 2002). These findings and other accumulating evidence support the importance of structural factors, such as working conditions and perceptions of employers’ attitudes, in promoting sexual health and safer sex behavior and further reinforce the notion that individual factors by themselves may be insufficient to produce long-term reduction in risky behavior (O’Leary et al., 2003). Consequently, attention has been directed at integrating structural environments with individually focused interventions, particularly among such vulnerable populations as FCSWs. The Thai 100% Condom Program is a successful example of such an intervention. This initiative targeted all Thai brothel-based commercial sex workers on their consistent condom use (Hanenberg & Rojanapithayakorn, 1998). Other projects have also yielded great success in improving condom use among female sex workers (Hanenberg, Rojanapithayakorn, Kunasol, & Sokal, 1994). In a study in the Dominican Republic, environmental–structural factors proved to be a major predictor of consistent condom use among female sex workers (Kerrigan et al., 2003). The Sonogachi study in India identified significant improvements in condom-use behavior among groups of sex workers assigned to peer education interventions (Basu et al., 2004). In a study in Madagascar, 1,000 sex workers were randomly assigned to two study arms: peer education supplemented by risk-reduction counseling by a clinician versus condom promotion by peer educators only. Follow-up results at 6 months indicated significant reductions in STI for sex workers assigned to the peer education plus risk-reduction counseling, compared with increases in STI for the peer education-only group (Feldblum et al., 2005).

Prior research in the Philippines indicates that condom policies and other contextual (e.g., structural–environmental) factors in the establishments appear to interact with individual cognitive (e.g., decision-making) factors in influencing change in risky behavior among FCSWs (Morisky, Chiao, Stein, & Malow, 2005; Morisky, Pena, Tiglao, & Liu, 2002; Morisky, Stein, et al., 2002; Morisky et al., 1998; Tiglao, Morisky, Tempongko, Baltazar, & Detels, 1997). For instance, employers’ actual support for condom use and their perceived support were shown to influence condom-use behaviors among individual FCSWs significantly (Morisky, Stein, et al., 2002). The women were more likely to practice condom-use behavior associated with their work when their employers encouraged these behaviors. Furthermore, the relationship remained robust even after statistically adjusting for the variability associated with salient individual and work site characteristics. The more FCSWs perceived that they had their employer’s support, the more likely they were to use condoms during sex (Morisky, Stein, et al., 2002).

Because social influence models have not been often studied in the HIV prevention area, we present an evaluation of how the models’ constructs operated in an intervention in a real-world community-based setting. In the current study, four communities were randomly assigned to one of three intervention groups or a control group that varied in targeting personal factors (perceived risk to HIV, AIDS knowledge, and attitudes toward condoms) and structural factors (establishment attitudes concerning condom use as well as other establishment characteristics inherent in the work-place, such as policies and rules about using condoms and condom availability). For our outcome measure, we examined the relationship between varying social influence-oriented interventions and subsequent STI reduction and condom use.

We hypothesized that a social influence intervention would have a significant effect on promoting condom use and reducing STI infection. We varied the types of influence by including a manager-only condition, a peer-influence-only condition, and a combined manager and peer influence condition. Because the women were clustered within establishments, a multilevel approach was used to assess personal, structural, and intervention effects in the prediction of condom use and STI infections.

Conceptual Framework

The interventions were based on a blend of social–cognitive theory at the individual level and social influence theory at the organizational level. According to social–cognitive theory (Bandura, 1987), behavior change is enhanced by training individuals to exercise influence over their own behaviors and their social environment. This situation is best achieved not only by intervening for heightened awareness and knowledge but also by enhancing resources and social support. Bandura (1987) has conceptualized the basic elements of social–cognitive theory to consist of personal determinants in the form of cognitive, affective, and biological factors, behavior, and the environment. This theoretical framework was applied to HIV/AIDS-related behaviors by exposing participants to interventions designed not only to promote safer sex guidelines but also to develop individual skills and self-beliefs that would enable risk reduction in the face of counteracting influences (Bandura, 2004).

The second theoretical framework used in this research consists of power and social influence. The social psychological study of power and influence finds its origin in the groundbreaking work of Kurt Lewin (Lewin, 1941), who defined power as the possibility of inducing force on someone else or, more formally, as the maximum force Person A can induce on Person B divided by the maximum resistance that Person B can offer. This conceptualization of power and social influence was further developed by French and Raven (1959), who defined influence as a force one person (the agent) exerts on someone else (the target) to induce a change in the target, including changes in behaviors, opinions, attitudes, goals, needs, and values. Social power was subsequently defined as the potential ability of an agent to influence a target. Raven (1965) further classified the six bases of power to include reward, coercive, legitimate, referent, expert, and informational power.

Method

Participants

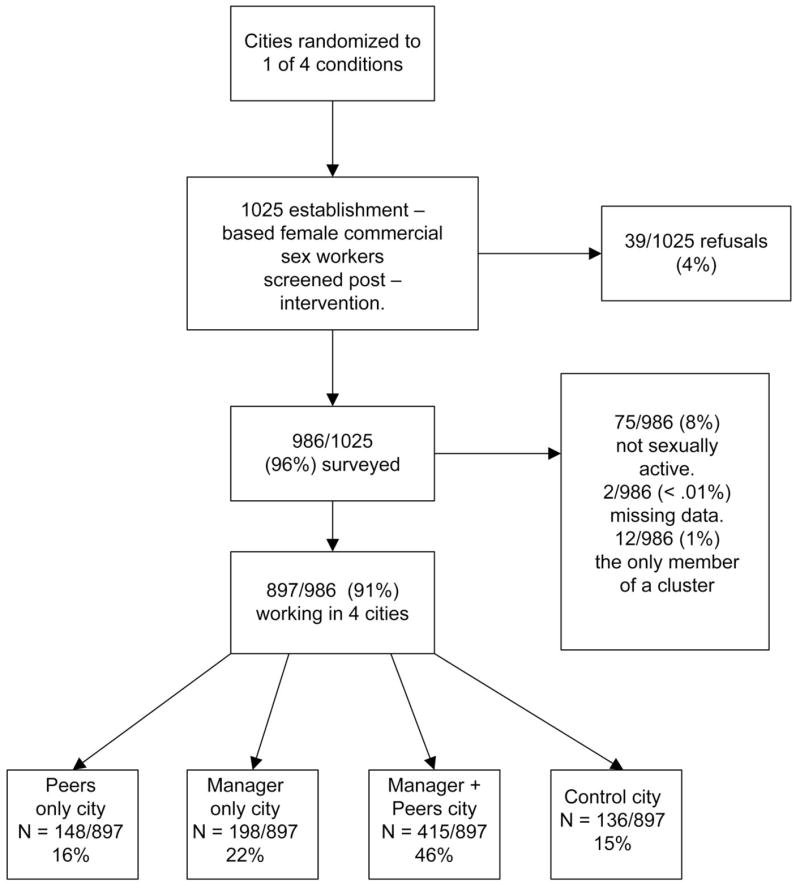

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 986 Filipinas working for establishments in which they were required to attend social hygiene clinics either weekly or bimonthly, depending on the schedule of the clinic. They worked at nightclubs, disco bars, beer gardens, and karaoke bars. Originally, 1,025 women were approached for interviews, and 39 refused to participate. Also excluded from the current multilevel analysis were 75 women who stated that they had never had vaginal, anal, or oral sexual experiences; 2 women who were missing several data points; and 12 women who worked alone in their establishments. This procedure left a total of 897 women. The surveys were extensively pretested in small focus groups in the Philippines for appropriateness to the educational levels of the women and for cultural relevance and sensitivity. Most surveys were conducted in the social hygiene clinic, although a few were conducted in business establishments or residences. The 897 FCSWs ranged in age from 15 to 41 years (mean age = 22.5 years). They averaged 9 years of education, and 10% were married. See Figure 1 for a flowchart depicting the participation process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participation in the study by female commercial sex workers in the randomized intervention cities.

Cluster Information

Among the 897 women, there were 103 establishments within which the women were clustered. These clusters ranged in size from 2 to 47. The average size was 8.7 women per cluster.

Measures

The survey was designed to include items that would reflect several underlying latent constructs hypothesized as important in predicting condom use and other health outcome indicators of safe sex (STIs), especially constructs of most relevance to FCSWs (Morisky, Pena, et al., 2002; Morisky, Stein, et al., 2002; Morisky et al., 1998; Tiglao et al., 1997). Preliminary exploratory factor analyses of the data were conducted on subsets of the theoretically important measured variables by using maximum likelihood factor analyses with direct quartimin oblique rotation. Items that loaded highly together were used as manifest indicators of their proposed underlying constructs. Generally, cutoff scores of .40 or higher were considered acceptable. The latent constructs were developed as described below.

Perceived risk

This construct was indicated by two scaled items that asked (a) how worried the FCSW was about getting AIDS on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all worried) to 5 (extremely worried), and (b) her chances of getting AIDS on a scale ranging from 1 (none) to 5 (very great).

AIDS knowledge

A knowledge index was constructed with four variables in order to have multiple indicators for this index (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Two variables were means of correct responses to 10 factual items scaled 0–1 (Know Facts 1, Know Facts 2). Each parcel contained 5 items that were combined at random (e.g., Do you think people can catch AIDS by blood transfusion? Do you think people can catch AIDS by drug use/sharing needles?). Items were rescaled if necessary so that higher scores indicated correct responses.

The other two variables were based on a nine-item index that assessed the women’s knowledge of risk behaviors, which was scored on a scale ranging from 1 (no risk) to 5 (a great risk; e.g., How risky is it to have sexual intercourse with someone who injects drugs? How risky is sexual intercourse with someone you do not know very well without using a condom?). Two variables were constructed from the nine items with the means of five and four items, respectively (Know Risk 1, Know Risk 2). These parcels were constructed randomly as well. Items were rescaled if necessary so that higher scores indicated correct responses.

Establishment practices

Items in this latent construct were concerned with rules and communications from the establishment in which the FCSWs were working. These were yes–no items (0 = no, 1 = yes) that asked (a) whether a coworker at an FCSW’s establishment tried to convince her to use a condom with a customer, (b) whether her establishment has a rule that all workers must use condoms when having sex with customers, (c) whether condoms are available at her establishment for the workers who work there, and (d) whether her boss ever talked to her about using condoms.

Condom attitude

Three indicators represented endorsement of positive ideas about condom use on the basis of a series of scaled statements about condom use ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). These were parcels created from the means of six items (two per parcel). Typical items were “Condoms can prevent STIs if used properly” and “Condoms are easy to use.”

Outcome variables: Condom use

The first outcome variable was whether the FCSWs had used a condom the last time they had sex with a customer (0 = no, 1 = yes). Previous research ruled out a potential social desirability bias by a nonsignificant relationship with the Marlow–Crown Scale of Social Desirability (Morisky, Ang, & Sneed, 2002). As an indicator of safe sexual practices, the number of STIs they had in the past 6 months was assessed. Accuracy of these responses was bolstered by the fact that FCSWs were tested regularly at the clinic where they also were interviewed. Self-reports were collected at pre- and postintervention.

Intervention status indicators

Three orthogonal polynomials were constructed to reflect possible intervention group membership. Contrast coding was as follows: (a) control group membership was given a score of 3, and all others were given a score of −1; (b) combination group membership was indicated by giving combination group members a score of 2, control group members a score of 0, and others a score of −1; (c) peer versus manager group membership was scored by giving peers a value of −1, managers a value of 1, and all others a 0.

Analyses

The EQS structural equations program (Bentler, 2005) was used to estimate a two-level model using a maximum likelihood approach (Bentler, 2005; Bentler & Liang, 2002). If individual subjects are nested within meaningful clusters and used in a single aggregated database, observations may not be independent. In this case, standard statistical methods are not applicable, and special adjustments are needed to compute standard errors and goodness-of-fit chi-square tests (Muthén & Satorra, 1995). This can be achieved by modeling both levels and by adjusting for nonindependence of observations within the modeling procedure. The between-levels portion of the multilevel model in this study was of particular interest in assessing the impact of the intervention. Effect of intervention status could not be analyzed in the within-subjects portion of the model because, of course, all FCSWs within a cluster (establishment) had the same value for their intervention status because the intervention was implemented at the city level.

We initially determined whether a multilevel model was appropriate by assessing the intraclass correlations among the indicator variables. The intraclass correlation coefficient reflects the degree of similarity or correlation between subjects within a cluster. In this current case, the cluster is women working within one establishment. The intraclass correlation is estimated as the ratio of between-cluster variance divided by the sum of within- and between-cluster variance on a given variable. If significant nonzero intraclass correlations are obtained, the assumption of independent observations is violated (Muthén, 1994).

Goodness of fit of the models was evaluated with the Bentler–Liang likelihood ratio statistic (BLLRS), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Bentler, 2005). The CFI, which ranges from 0 to 1, reports the improvement in fit of the hypothesized model over a model of complete independence or lack of relationship among the measured variables and adjusts for sample size. Values equal to or greater than .95 are desirable and indicate that close to 95% of the covariation in the data is reproduced by the hypothesized model (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The RMSEA is a measure of lack of fit per degrees of freedom, controlling for sample size, and values less than .06 indicate a close-fitting model (Ullman & Bentler, 2003).

An initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) tested the factor structure (measurement model) of the hypothesized model and also provided correlations among all of the factors and the orthogonal polynomials representing group membership. Once the factor structure was confirmed, a predictive structural model was tested to assess the influence of intervention group membership, perceived risk, knowledge, establishment practices, and condom attitudes on the outcomes of using a condom during the last sexual encounter and incidence of STIs. Of main interest was the between-groups model. Nonsignificant paths and covariances were dropped gradually by using the suggested model-evaluation procedure of MacCallum (1986). Predictive paths from the intervention-status orthogonal polynomials were not dropped to keep orthogonality intact.

To assess possible preexisting differences between the cities (city membership was confounded with intervention status), we conducted a supplementary analysis that contrasted selected behaviors and attitudes measured in the same manner before and after the intervention by city by using multisample structural equation modeling and comparisons of latent means at the city level (Bentler, 2005). Because the same women were not available at the baseline and at the posttest, longitudinal assessments of change were not possible. We also compared the cities before the intervention by using multisample modeling and latent means analysis using the control city as the reference group.

Intervention and Procedures

Four large cities (population > 200,000) located approximately 250 miles south of the Philippines capital (Manila) served as intervention sites. Research staff met with the regional medical officer, the city health officer, and the owner or manager of each establishment to discuss the objectives and other aspects of the project, including the meaning of being randomized to the intervention or control group comparison condition. All organizations agreed to participate. Human subject approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of the Philippines. The four participating sites were randomly assigned to one of the intervention groups (peer counseling, manager training, or the combination of peer counseling and manager training) or to a standard control group.

The peer counseling intervention was implemented in all participating establishments in Site 1 (Legaspi City). In consultation with the manager or owner, two FCSWs from each establishment were selected and trained during a 5-day period at a nearby location. Travel allowances and a daily stipend were provided to defray expenses and lost work time. Content areas of the training program included basic information on STI and HIV, modes of transmission, interpersonal relationships with peers and clients in the work establishment, sexual negotiation, role playing and modeling, and normative expectancies. The peer educators in each site met monthly with the site coordinator and discussed issues related to sexual negotiations with customers, where these negotiations took place, and establishing limits regarding sexual behavior, alcohol influence, and condom-use negotiations with the customer.

The manager training intervention in Site 2 (Cagayan de Oro City) consisted of the same topics as the peer counseling intervention with additional training on the social influence role of managers–supervisors by providing positive reinforcement of their employees’ healthy sexual practices. Managers were trained to implement a continuum of educational policies, beginning with current practices and gradually increasing to greater levels of involvement. These policies consisted of meeting regularly with their employees, monitoring their attendance at the social hygiene clinic, providing educational materials on HIV/AIDS prevention, reinforcing positive STI prevention behaviors, attending monthly managers’ advisory committee meetings, promoting AIDS awareness in the establishments (through posters, pamphlets, and brochures), providing educational materials to customers, making condoms available to FCSWs as well as to customers, and having a 100% oral and written condom-use policy. Managers and floor supervisors assigned to the manager training intervention met with the site coordinator each month throughout the duration of the program. Topics discussed by the managers–supervisors included retention of FCSWs, protocol to be followed when recruiting FCSWs already working in a local establishment, role of managers–supervisors in the reinforcement of safe sexual behaviors, starting an insurance fund for FCSWs who could not afford a complete medical regimen, and the establishment of educational policy in the workplace (Morisky, Pena, et al., 2002).

The combined intervention of peer counselors and manager training was implemented in two contiguous cities located in Site 3 (Lapu-Lapu and Mandawe Cities, each located in the Cebu City region). Participants received all of the training and attended monthly meetings as described above. Site 4, the control site, was located in Ilo-Ilo City. All sites are geographically dispersed throughout the southern Philippines.

Results

City Comparisons

Within cities

The same women were not consistently available at baseline and again at follow-up. Thus, comparisons were done at the city level. Questions that were worded the same and were available at baseline and follow-up were used in analyses contrasting knowledge, establishment practices, condom attitudes, condom use during the last sexual episode, and self-reported STI. Women in all cities reported greater levels of HIV/AIDS knowledge at follow-up, which might be due to a historical trend based on educational efforts throughout the Philippines. Women in the control cities at follow-up reported higher knowledge than at baseline (p < .001), lower establishment practices (p < .001), lower condom attitudes (p < .01), and less condom use during the last sexual episode at follow-up than at baseline (p < .001). Women in the peer influence condition reported considerably more knowledge (p < .001), lower establishment practices (p < .01), and better condom attitudes (p < .001) at follow-up. Women in the manager group reported considerably more knowledge (p < .001) and lower establishment practices (p < .001) and were more likely to have used a condom during the last sexual episode (p < .001). Women in the combination group reported considerably more knowledge (p < .001), better establishment practices (p < .05), and a better condom attitude (p < .001) and were more likely to have used a condom during the last sexual episode (p < .001).

Across cities at baseline

We performed a four-group multi-sample analysis by using the control group as the reference group. It was unlikely that the groups would be exactly alike beforehand, but it was important that the control group not be the most disadvantaged in terms of behaviors and attitudes before the interventions were implemented. Indeed, the peer-intervention city women reported higher knowledge (p < .001) and lower establishment practices (p < .001) and condom attitudes (p < .001) and were much less likely to have used a condom during the last sexual episode (p < .001). The women in the manager intervention reported no difference in knowledge, no difference in establishment practices, a significantly lower condom attitude (p < .001), and less condom use the last time they had sex with a partner (p < .05). The women in the combination-group cities reported less knowledge (p < .05), lower establishment practices (p < .001), and lower condom attitudes (p < .05) and were less likely to have used a condom the last time they had sex with a partner (p < .01). Thus, there was no preexisting advantage for the combination group. Rather, it appears to have been the most disadvantaged.

Further supplemental analyses were conducted to assess self-reported condom use behavior and STI at pre- and postintervention among the participating study sites. As noted in Table 1, statistically significant differences were found between the study sites with respect to condom use at last sexual encounter for both pre-and postintervention. Table 2 presents self-reported STI at similar points in time. At preintervention, no significant differences were found among the four study groups, but significant differences were noted at postintervention for the manager training group (p < .05) and the combined intervention group (p < .001).

Table 1.

Self-Reported Condom Use at Last Sex With a Customer Before Intervention and After Intervention Among FCSWs in Four Study Sites in the Philippines

| Legaspi: peer education | Cagayan de Oro: manager training | Cebu: combined | Ilo-Ilo: control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preinterventiona | 14.4% | 20.1% | 35.2% | 45.6% |

| Postinterventionb | 15.9% | 24.1% | 50.8% | 20.1% |

Note. FCSWs = female commercial sex workers.

χ2(3) = 51.4, p ≤ .001.

χ2(3) = 103.2, p ≤.001.

Table 2.

Self-Reported Sexually Transmitted Infections Before Intervention and After Intervention Among FCSWs in Four Study Sites in the Philippines

| Legaspi: peer education | Cagayan de Oro: manager training | Cebu: combined | Ilo-Ilo: control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention | 44.3 | 28.4 | 31.8 | 43.6 |

| Postintervention | 37.9 | 19.2 | 10.6 | 41.7 |

| Difference | −6.4 | −9.2* | −21.2*** | 31.9 |

Note. FCSWs = female commercial sex workers.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤.001.

Multilevel Postintervention Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The fit indexes for the initial CFA were excellent: BLLRS χ2(181, N = 897) = 325.64, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03 (90% confidence interval = .025 to .035). All of the factor loadings of the measurement model were significant (p < .001). Table 3 reports the between-level factor loadings and the intraclass correlations. The intraclass correlations were substantial, indicating that the associations among women within establishments could not be ignored and that a multilevel analysis was appropriate. The correlations mean that women within the clusters were more alike than women across the clusters.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, Ranges, Between-Level Factor Loadings, and Intraclass Correlations (ICCs) of Variables in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Variable | M | SD | Factor loading between-level | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived risk (1–5) | ||||

| Chances you get | 2.51 | 1.50 | .97 | .15 |

| How worried | 3.39 | 1.51 | .89 | .12 |

| 2. Knowledge | ||||

| Know facts 1 (0–1) | 0.83 | 0.17 | .86 | .11 |

| Know facts 2 (0–1) | 0.66 | 0.19 | .83 | .12 |

| Know risk 1 (1–5) | 4.05 | 0.56 | .95 | .23 |

| Know risk 2 (1–5) | 4.34 | 0.58 | .56 | .07 |

| 3. Establishment practices (0–1) | ||||

| Coworker convince | 0.37 | 0.48 | .83 | .19 |

| Condom rules | 0.47 | 0.48 | .98 | .52 |

| Condom available | 0.35 | 0.47 | .95 | .64 |

| Boss talk about condoms | 0.42 | 0.49 | .94 | .43 |

| 4. Condom attitudes (1–5) | ||||

| Attitude 1 | 3.93 | 0.69 | .88 | .19 |

| Attitude 2 | 4.09 | 0.63 | .72 | .06 |

| Attitude 3 | 3.74 | 0.87 | .84 | .11 |

| 5. Number of STIs (0–2) | 0.28 | 0.55 | 1.00 | .10 |

| 6. Used condom last time (0–1) | 0.32 | 0.47 | 1.00 | .51 |

Note. STIs = sexually transmitted infections.

Table 4 presents the correlations among the latent variables in the between-levels analysis. For the substantive latent variables, several correlations among them were quite large. Higher perceived risk was associated with less knowledge, more establishment practices, and having used a condom at last sexual encounter. More knowledge was associated with more positive condom attitudes. Establishment practices were highly associated with positive condom attitudes and having used a condom at last sexual encounter. Positive condom attitudes were highly associated with having used a condom at last sexual encounter.

Table 4.

Between-Level Correlations Among Latent Variables and Intervention Status Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived risk | — | ||||||||

| 2. Knowledge | −.54*** | — | |||||||

| 3. Establishment practices | .53*** | −.03 | — | ||||||

| 4. Condom attitudes | .02 | .48*** | .66*** | — | |||||

| 5. Number of STIs | −.03 | 3.08 | −.06 | .10 | — | ||||

| 6. Used condom last time | .48*** | .16 | .90*** | .65*** | −.25* | — | |||

| 7. Control group | .41*** | −.85*** | −.04 | −.48*** | −.04 | −.19* | — | ||

| 8. Combination group | −.07 | .20* | .51*** | .68*** | −.30*** | .47*** | −.12 | — | |

| 9. Peers vs. managers | .51*** | 3.14 | −.06 | −.33** | −.21* | .03 | −.04 | −.07 | — |

Note. STIs = sexually transmitted infections.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤.01.

p ≤.001.

Associations with intervention status were also of great interest. Control group membership was associated with higher perceived risk, less knowledge, lower condom attitudes, and less likelihood of using a condom at last sexual encounter. Combined group membership was associated with more knowledge, having better establishment practices, better condom attitudes, fewer STIs, and more likelihood of using a condom at last sexual encounter. In the manager-only versus peer-only contrast, those with the manager intervention were more likely to report higher perceived risk, lower condom attitudes, and fewer STIs.

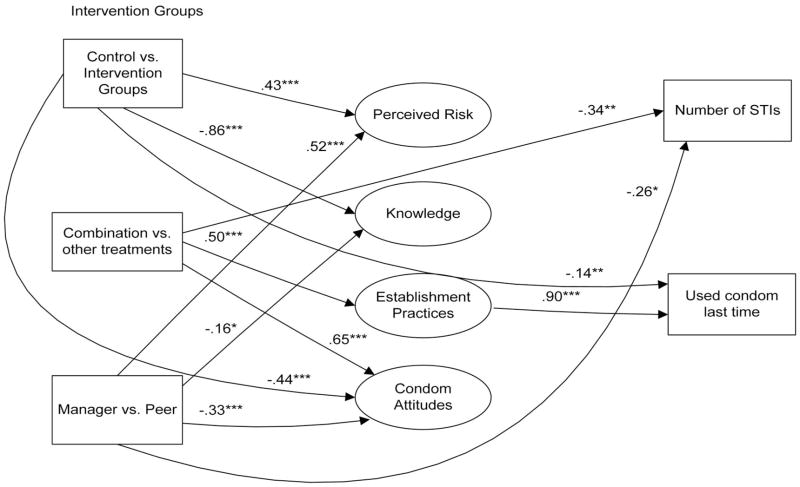

Multilevel Postintervention Structural Model

Figure 2 presents the final structural model in the multilevel between-groups analysis. The fit indexes of the final single model were very good: BLLRS χ2(204, N = 897) = 340.89, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03 (90% confidence interval = .022 to .032). Those that were in the combined intervention group reported fewer STIs in the past 6 months. They also reported more procondom establishment practices and better condom attitudes. Those in the control group were less likely to use a condom the last time they had sex with a customer. They also reported greater perceived risk, less knowledge, and poorer condom attitudes. In the manager versus peers contrast, those in the manager-only group reported lower condom attitudes, less knowledge, higher perceived risk, and fewer STIs.

Figure 2.

Significant regression paths among variables in the between-levels structural model. Intervention groups were contrast coded as follows: (a) control group = 3, all others = −1; (b) combination group membership = 2, control group = 0, others = −1; (c) manager = 1, peer = −1, all others = 0. Regression coefficients are standardized. STIs = sexually transmitted infections. *p < .05. **p <.01. ***p < .001.

There was also a very large significant effect of establishment practices on condom use during the last sexual encounter (regression coefficient = .90). In the bivariate analysis reported above (CFA), combination group membership was also highly associated with use of a condom during the last sexual encounter (correlation = .47). The very large effect of establishment practices on condom use captured the greatest amount of variance and prevented a significant direct effect of combination group membership on condom use the last time FCSWs in this group had sex with a customer. However, the indirect effect of combination group membership mediated through establishment practices was very strong (p < .001; standardized regression coefficient = .46).

Discussion

The four conditions of this research design included a peer influence condition, a manager influence condition, a combined peer–manager influence condition, and the control condition. The combined group had the most positive outcomes. Results of the path model indicated that participants in the combined peer–manager condition were significantly more likely to reduce HIV sexual risk, in that they showed more positive attitudes toward condom use and also reported that their establishments were more likely to promote condom use. Such establishment policies in turn were extremely strong predictors of condom use. They also reported significantly fewer STIs than did other study participants. In bivariate analyses, they also reported more likelihood of using a condom the last time they had sex and had more knowledge than other study participants. These results are consistent with those found in the study of Koniak-Griffin et al. (2003), who used social–cognitive theory in an HIV prevention intervention with U.S. adolescent mothers, and with the findings of van Empelen et al. (2003) regarding HIV prevention studies with injection drug users, which suggests that interventions grounded in social–cognitive theory or diffusion of innovations are likely to provide successful outcomes.

Those with either a peer-only influence intervention or a manager-only intervention demonstrated improvement over the control group but did not show consistent improvement in all areas. It was interesting that those with the manager-only intervention had fewer STIs even though they had more negative condom attitudes and less knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Those women in the peer-only intervention had better attitudes and greater knowledge but perhaps had not had the impetus to apply those attitudes and knowledge to actual behavior change without the input of their manager.

Consistent with a participatory action research approach (see Morisky, Ang, Coly, & Tiglao, 2004), our multilevel intervention was based on a thorough needs assessment at the individual, community, and organization levels. This included in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with key informants and stakeholders (both in bars and city health departments). Our intervention design addresses individual-level changes (beliefs and attitudinal changes within the bar workers and managers) and social structural–environmental changes (increased access to condoms, policy changes within the establishments). This intervention transcends the typical microlevel individual-education approach to increase condom use among FCSWs. It involved a macrolevel structural approach via peer education among and for FCSWs (Swendeman, Thomas, Chiao, Sey, & Morisky, 2005). Further, consistent with the study of Fang, Stanton, Li, Feigelman, and Baldwin (1998) among African American adolescents, it included bar managers as an added layer of influence in facilitating HIV risk reduction among female bar workers. This was also accomplished through two important social influence constructs conceptualized by Raven (1965), namely, referent and informational power on the part of both establishment managers and peer educators.

Training establishment owners or managers and floor supervisors to influence their employees’ social hygiene, beyond viewing what transpires as business transactions, entailed that those in supervisory positions would (a) oversee registration and attendance of their employees in a social hygiene clinic, (b) provide STI educational materials and training related to HIV risk reduction, (c) distribute condoms to employees and customers, and (d) create and establish a 100% condom-use policy by all employees.

Limitations of Study

Although theoretically driven, and, perhaps most important, a step toward developing macrolevel structurally relevant HIV interventions that may be sustainable and generalizable beyond commercial sex workers in the Philippines, there are some notable limitations. Valid inference was premised on assuming a reasonable similarity among the four targeted cities, each of which was exposed to one of the four intervention conditions. We acknowledge that city is confounded with intervention status. Controlled experiments, where subjects can be randomly assigned to receive interventions, are desirable but are often infeasible or overly burdensome, especially in our research settings. Therefore, the cluster-randomized design adapted in this study is often used by others as the only feasible and practical method of inquiry. Although they are typically less intrusive and less costly, they require bolder assumptions, which are important but usually not testable. As Rogers, Ying, Xin, Fung, and Kaufman (2002) suggested, geography, by itself, can introduce variables related to commercial sex workers and bar manager attitudes, beliefs, values, and relative status that, in this instance, went uncontrolled. Cities may well differ in significant political, economic, social, and cultural facets, which might affect the outcomes with respect to risky sexual behavior and condom use. Our analyses of the cities before the intervention indicated various differences among the cities. It is worth noting that the control city was, if anything, superior in many ways to the other cities before the intervention. Our comparisons among the baseline city variables indicated this. However, at the follow-up, the women in the control city actually had a decrement in the positive behaviors under study except for knowledge, which showed an increase. As indicated above, all of the cities showed an appreciable increase in knowledge, although the increase was not as great for the control city. Furthermore, the combined treatment city was, if anything, the worst at baseline yet demonstrated the greatest advantage after the intervention.

Suggestions for Future Research

Although health department employees were consulted in designing the intervention, it may be beneficial to extend the macrolevel structural approach by including greater direct involvement by community agencies as well as other sectors of local government to promote condom use in such establishments (Parkhurst & Lush, 2004). Before bar managers and owners will commit fully to a macrolevel structural approach encouraging condom use among their FCSWs and clients, both the message and the behavior of a variety of governmental agencies must be nonambiguous. Research on the public policy aspects of coordinating such support, via city ordinances, inspections, certificates, and so forth, is central to extending the macrolevel approach to a city’s environmental and structural support systems. Such research efforts would be consistent with the recommendations of the Kerrigan et al. (2003) study with FCSWs in the Dominican Republic as well as the even broader suggestions of Riedner et al. (2003) in their study of female bar workers in Tanzania. The latter called for improved access to affordable health care, including STI services. Whereas the above studies promoted condom use among FCSWs and bar owners, Chillag et al. (2002) recommended that sociocultural, organizational, and individual client factors also need to be addressed in designing and implementing community-level HIV prevention interventions. Further research in this area, leading to a greater understanding of these factors, is warranted.

Finally, future studies might consider the possible role of the mass media in creating a supportive environment for those at risk with respect to HIV and STI. In addition to increasing basic AIDS knowledge and presenting important factual information about the importance of condom use, media messages might also help legitimize appropriate condom use through normative expectancies.

Conclusion

This study moved toward a more encompassing macrolevel approach via inclusion of establishment managers, FCSW peer groups, and public health officials in risk-reduction interventions. The combined manager–peer education approach showed greater impact in facilitating desirable outcomes than did any other experimental condition.

However, for condom use to become commonplace among Filipino FCSWs, the financial penalty for their use must be minimized, and that will require educational programs targeted toward acceptance of condoms by clients, civic organizations, and governmental agencies. As recently discussed by Liao, Schensul, and Wolffers (2003) in their study of Chinese hospitality workers, a female bar worker’s need for money will overshadow concerns about her personal health until and unless clients, and others, become far more accepting of condom use. Establishment owners must also believe that the benefits of condom use outweigh the costs and actively promote their use. With support from an employer and acceptance by a client, an FCSW can more comfortably use condoms and lower, to a substantial degree, the probability of contracting an STI.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R01-AI33845 to Donald E. Morisky and National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant P01-DA-01070-32 to Judith A. Stein. We extend appreciation to Teodora V. Tiglao (co-principal investigator); Angie Casas, Lolipil Gella, Daisy Mejilla, Charlie Mendoza, Dorcas Romen, and Mildred Publico (site coordinators); and Gisele Pham (manuscript production).

Contributor Information

Kate Ksobiech, Medical College of Wisconsin.

Robert Malow, Florida International University, Miami.

References

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist. 1982;37:122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection; Paper presented at the National Institute of Mental Health Drug Abuse Research Conference on Women and AIDS; Bethesda, MD. 1987. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Lee SJ, Newman P, Weiss R. HIV prevention among sex workers in India. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36:845–852. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Liang J. Two-level mean and covariance structures: Maximum likelihood via an EM algorithm. In: Duan N, Reise S, editors. Multilevel modeling: Methodological advances, issues, and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chillag K, Bartholow K, Cordeiro J, Swanson S, Patterson J, Stebbins S, et al. Factors affecting the delivery of HIV/AIDS prevention programs by community-based organizations. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(Suppl A):27–37. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.4.27.23886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Stanton B, Li X, Feigelman S, Baldwin R. Similarities in sexual activity and condom use among friends within groups before and after a risk-reduction intervention. Youth & Society. 1998;29:431–450. doi: 10.1177/0044118x98029004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum PJ, Hatzell T, Van Damme K, Nasution M, Rasamindra-kotroka A, Grey TW. Results of a randomised trial of male condom promotion among Madagascar sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:166–173. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P, Meliawan P, MacDonald K, Thorpe L. Behavioral interventions for reduction of sexually transmitted disease/HIV transmission among female commercial sex workers and clients in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS. 1996;10:213–222. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French JRP, Jr, Raven BH. The bases of social power. In: Cartwright D, Zander AF, editors. Studies in social power. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 1959. pp. 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hanenberg R, Rojanapithayakorn W. Changes in prostitution and the AIDS epidemic in Thailand. AIDS Care. 1998;10:69–79. doi: 10.1080/713612352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanenberg RS, Rojanapithayakorn W, Kunasol P, Sokal DC. Impact of Thailand’s HIV-control programme as indicated by the decline of sexually transmitted diseases. Lancet. 1994;344:243–245. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Ellen JM, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano DD, Sweat M. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Nyamathi A, Uman G, Stein JA, Cumberland WG. Project CHARM: An HIV prevention program for adolescent mothers. Family & Community Health. 2003;26:94–107. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Analysis of the concepts whole, differentiation, and unity. University of Iowa Studies in Child Welfare. 1941;18:226–261. [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Schensul J, Wolffers I. Sex-related health risks and implications for interventions with hospitality women in Hainan, China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:109–121. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.109.23834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R. Specification searches in covariance structure modeling. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;100:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Ang A, Coly A, Tiglao TV. A model HIV/AIDS risk reduction program in the Philippines: A comprehensive community-based approach through participatory action research. Health Promotion International. 2004;19:69–76. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Ang A, Sneed C. Validating the effects of social desirability on self-reported condom use. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14:351–360. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.6.351.24078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Chiao C, Stein JA, Malow R. Impact of social and structural influence interventions on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female bar workers in the Philippines. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2005;17:45–63. doi: 10.1300/J056v17n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Pena M, Tiglao TV, Liu KY. The impact of the work environment on condom use among female bar workers in the Philippines. Health Education & Behavior. 2002;29:461–472. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Stein JA, Sneed CD, Tiglao TV, Liu K, Detels R, et al. Modeling personal and situational influences on condom use among establishment-based commercial sex workers in the Philippines. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Tiglao TV, Sneed CD, Tempongko SB, Baltazar JC, Detels R, Stein JA. The effects of establishment practices, knowledge and attitudes on condom use among Filipina sex workers. AIDS Care. 1998;10:213–220. doi: 10.1080/09540129850124460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Multilevel covariance structure analysis. Sociological Methods & Research. 1994;22:376–398. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. In: Marsden PV, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1995. pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Holtgrave D, Wright-DeAguero L, Malow RM. Innovations in approaches to preventing HIV/AIDS: Applications to other health promotion activities. In: Valdiserri R, editor. Dawning answers: How the HIV/AIDS epidemic has helped to strengthen public health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Martins P. Structural factors affecting women’s HIV risk: A life-course example. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S68–S72. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outwater A, Nkya L, Lwihula G, O’Connor P, Leshabari M, Nguma J, et al. Patterns of partnership and condom use in two communities of female sex workers in Tanzania. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2000;11:46–54. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst JO, Lush L. The political environment of HIV lessons from a comparison of Uganda and South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59:1913–1924. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Contraceptive attitudes and intentions to use condoms in sexually experienced and inexperienced adolescent males. Journal of Family Issues. 1990;11:294–312. doi: 10.1177/019251390011003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven BH. Social influence and power. In: Steiner ID, Fishbein M, editors. Current studies in social psychology. New York: Wiley; 1965. pp. 399–444. [Google Scholar]

- Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Hoffmann O, Nichombe F, Lyamuya E, Mmbando D, et al. Baseline survey of sexually transmitted infections in a cohort of female bar workers in Mbeya Region, Tanzania. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:382–387. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.5.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Ying L, Xin YT, Fung F, Kaufman J. Reaching and identifying the STD/HIV risk of sex workers in Beijing. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14:217–227. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.3.217.23892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendeman D, Thomas T, Chiao C, Sey K, Morisky D. Improving program effectiveness through results oriented approaches: An STI/HIV/AIDS prevention program in the Philippines. In: Haider M, editor. Global public health communication: Challenges, perspectives, and strategies. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2005. pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Tiglao TV, Morisky DE, Tempongko SB, Baltazar JC, Detels R. A community PAR approach to HIV/AIDS prevention among sex workers. Promotion and Education. 1997;3:25–28. doi: 10.1177/102538239600300411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology: Vol. 2. Research methods in psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- van Empelen P, Kok G, van Kesteren NMC, van den Borne B, Bos AER, Schaalma HP. Effective methods to change sex-risk among drug users: A review of psychosocial interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:1593–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Estimation of the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections. 2002 Retrieved February 16, 2004, from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/en/who_hiv_2002_14.pdf.