Abstract

Previous in vitro studies identified Secreted frizzled related protein 1 (SFRP1) as a candidate pro-proliferative signal during prostatic development and cancer progression. This study determined the in vivo roles of SFRP1 in the prostate using expression studies in mice and by creating loss-and gain-of-function mouse genetic models. Expression studies using an Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele showed that Sfrp1 is expressed in the developing mesenchyme/stroma of the prostate. Nevertheless, Sfrp1 null prostates exhibited multiple prostatic developmental defects in the epithelium including reduced branching morphogenesis, delayed proliferation, and increased expression of genes encoding prostate-specific secretory proteins. Interestingly, over-expression of SFRP1 in the adult prostates of transgenic mice yielded opposite effects including prolonged epithelial proliferation and decreased expression of genes encoding secretory proteins. These data demonstrated a previously unrecognized role for Sfrp1 as a stromal-to-epithelial paracrine modulator of epithelial growth, branching morphogenesis, and epithelial gene expression. To clarify the mechanism of SFRP1 action in the prostate, the response of WNT signaling pathways to SFRP1 was examined. Forced expression of SFRP1 in prostatic epithelial cells did not alter canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling or the activation of CamKII. However, forced expression of SFRP1 led to sustained activation of JNK, and inhibition of JNK activity blocked the SFRP1-induced proliferation of prostatic epithelial cells, suggesting that SFRP1 acts through the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway in the prostate.

Keywords: prostate development, SFRP1, non-canonical Wnt signaling, branching morphogenesis, JNK, knockout mice, transgenic mice

INTRODUCTION

Organogenesis of the prostate is initiated by fetal androgens during embryonic development and includes extensive branching morphogenesis that results in the formation of a complex ductal-acinar gland residing at the base of the bladder (Marker et al., 2003). The prostate is also the site of two common male diseases, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer that arise in distinct anatomic regions of the prostate (McNeal, 1983). The organization of both the developing and adult prostate includes two tissue layers, the prostatic epithelium and a supporting mesenchyme/stroma. During development, reciprocal cell-cell signaling between the epithelium and the surrounding developmental mesenchyme coordinates several developmental processes, while in the adult reciprocal cell-cell signaling between the prostatic epithelium and surrounding stroma maintain gland architecture and function. In recent years, it has also become clear that abnormal stromal-to-epithelial signaling is an important part of cancer progression in the prostatic epithelium (Cunha et al., 2004).

Following an earlier study demonstrating that fibroblasts isolated from prostatic adenocarcinomas could promote prostate cancer progression in adjacent epithelia (Olumi et al., 1999), we identified secreted frizzled related protein 1 (SFRP1) as a candidate stromal-to-epithelial paracrine signaling molecule over-expressed by cultured fibroblasts isolated from adenocarcinomas relative to cultured fibroblasts isolated from benign prostates (Joesting et al., 2005). Further evaluation of SFRP1 expression using real-time RT-PCR in developing mouse prostates and in cultured human cell lines demonstrated that expression levels paralleled prostatic growth rates with high expression during developmental growth, low expression in normal adult mouse prostate, and high expression in tumorigenic prostatic cell lines and cultured fibroblasts from prostatic adenocarcinomas. Forced expression of SFRP1 also increased proliferation in non-tumorigenic human prostatic epithelial cell lines. Collectively, these in vitro data identified SFRP1 as a candidate pro-proliferative stromal-to-epithelial paracrine signal during prostatic development and cancer progression. However, the status and functional roles of SFRP1 in the prostate in vivo remained untested.

In the mouse, prostatic development begins during late fetal stages, but most developmental growth, branching morphogenesis, and cellular differentiation occur between birth and reproductive maturity at approximately 5 weeks after birth. The prostate develops from the urogenital sinus (UGS), which arises by embryonic day 13 (e13) and remains morphologically ambisexual until around e17.5. At that time, androgen initiated and androgen dependent prostatic morphogenesis begins with the outgrowth of epithelial buds from the urogenital sinus epithelium (UGE) into the surrounding urogenital sinus mesenchyme (UGM). The epithelium initially invades the surrounding mesenchyme as solid epithelial cords that elongate within the UGM, bifurcate, and produce ductal side-branches to create a complex branched network of prostatic ducts (Risbridger et al., 2005; Sugimura et al., 1986). Branching morphogenesis is largely complete by 2 weeks after birth and ultimately gives rise to 3–4 bilaterally symmetrical prostatic lobes, each harboring a unique pattern of ductal branching (Hayward et al., 1996; Marker et al., 2003; Sugimura et al., 1986). During the initial phase of prostatic development, both the UGM and UGE are composed of undifferentiated cells. The epithelial cells forming the initial buds and elongating cords that invade the UGM co-express genes that later become restricted to specific differentiated cell types including cytokeratins 5, 8, 14, and 18 as well as p63 (Wang et al., 2001). As the epithelial cords mature into ducts containing a lumen, most epithelial cells differentiate into either luminal epithelial cells that express cytokeratins 8 and 18 or basal epithelial cells that express cytokeratins 5 and 14 as well as p63. Several minor epithelial cell populations are also present in maturing prostatic ducts including neuroendocrine cells, postulated transit amplifying cells, and candidate stem cells. As the prostate approaches reproductive maturity from 3–5 weeks after birth, luminal epithelial cells initiate expression of androgen-induced secretory proteins in a region-restricted manner in the adult prostate gland (Thielen et al., 2007).

Many years of genetic and experimental embryologic studies have investigated the roles of androgen signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in prostatic development. Androgens are necessary and sufficient to specify the UGS as prostate. This is shown by the absence of a prostate in Tfm mice that lack functional androgen receptors, and by the induction of a prostate in female UGSs treated with androgens (Brown et al., 1988; Cunha, 1975; He et al., 1994; Takeda et al., 1986) Experiments utilizing recombinant grafts of UGE and UGM from wild type and Tfm mice demonstrated the requirement for androgen receptor expression in the UGM, and not the UGE for prostatic bud induction and branching morphogenesis (Cunha and Lung, 1978; Donjacour and Cunha, 1993). These data led to the theory that one or more factors act in a paracrine fashion to stimulate prostatic development in the UGE. Several candidate paracrine factors expressed in the UGM such as FGF10 (Donjacour et al., 2003) and BMP4 (Lamm et al., 2001) have been investigated for their roles in prostatic development. However, known paracrine signals do not yet explain all of the paracrine interactions that have been inferred from experimental embryological studies. The initial data for Sfrp1 in the prostate (Joesting et al., 2005) raised the possibility that it may also act as a paracrine regulator of epithelial development in the prostate.

Sfrp1 is one of 5 structurally related genes that encode secreted proteins homologous to the Frizzled receptors for WNT ligands (Rattner et al., 1997). SFRP1 has been reported to bind WNT ligands and modulate their signaling activity (Dennis et al., 1999; Uren et al., 2000). Expression studies using in situ hybridization demonstrated strong Sfrp1 expression at developmental time points in the mouse kidney, heart, salivary gland, bone, teeth, and brain (Bodine et al., 2004; Esteve et al., 2003; Garcia-Hoyos et al., 2004; Jaspard et al., 2000; Leimeister et al., 1998). Despite this broad expression, experiments utilizing Sfrp1 knockout mice have thus far revealed more anatomically restricted phenotypes in the developing bone (Bodine et al., 2004). In addition, experiments using double knockout mice for both Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 demonstrated a crucial but redundant role for these genes during early embryogenesis (Satoh et al., 2006). These previous studies did not report a detailed analysis of prostatic development in Sfrp1 knockout mice.

In the present study, the roles of SFRP1 in the prostate were determined through expression studies and by creating loss- and gain-of-function mouse models. Sfrp1 was expressed in the developing mesenchyme of the mouse prostate. Sfrp1 loss-of-function mutants exhibited multiple prostatic developmental defects including reduced branching morphogenesis, delayed proliferation, and increased expression of genes encoding prostate-specific secretory proteins while gain-of-function transgenics gave opposite effects including prolonged epithelial proliferation and decreased expression of genes encoding secretory proteins. Forced expression of SFRP1 in cultured prostatic epithelial cells also led to sustained activation of JNK that was essential for SFRP1-induced epithelial proliferation, suggesting that SFRP1 acts through the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway in prostatic epithelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Sfrp1 mutant mice

The Sfrp1 targeting vector was derived from a genomic clone containing the first exon that had been isolated from a lambda 129SV library. The short arm of the targeting vector was a 1.1 kb DNA fragment corresponding to genomic sequence immediately upstream from the ATG start codon of the Sfrp1 gene. This element was generated by PCR using primer SFRPA2 (5’-TCTTGAGTTGGTATCCACCCAC-3’), which marked the 5’ end of the arm, and primer SFRPA1 (5’-ATACGGTTGCTCGGCGACGTC-3’), located just in front of the start codon. The Sfrp1 exon 1 coding sequence immediately downstream from the ATG was replaced with a LacZ/Neo selection cassette. The long arm was a 12.5 kb genomic fragment which began at the Kpn1 site of Sfrp1 intron 1 and extended beyond the RV site to the end of the lambda clone.

Ten micrograms of targeting vector was linearized by NotI digest and introduced into 129/Sv embryonic stem cells by electroporation. After selection in G418, surviving colonies were expanded and PCR analysis performed to identify clones that had undergone homologous recombination. PCR was conducted using primer SFRPA4 (5’-TGGGGGAGGCTAGAGGACGAC-3’), corresponding to sequence 100 bp upstream of the short arm, and primer LZ1 (5’-CGATTAAGTTGGGTAACGCCAGG-3’), located within the LacZ gene, approximately 100 bp from its 5’-end. Positive clones yielded the expected 1.3 kb fragment. Correctly targeted ES cells were microinjected into C57BL/6J host blastocysts. Chimeric mice were generated that provided germline transmission of the disrupted Sfrp1 gene. Mice carrying the targeted allele were mated with C57BL/6J mice, yielding offspring with a mixed genetic background.

LacZ staining

Beta-galactosidase activity in whole embryos was examined as previously described (Whiting et al., 1991). X-gal stained embryos were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS, and processed in a glycerol series to 80% glycerol for photography and storage. Whole embryos were photographed on a Leica MZFLIII stereoscope. For analysis of postnatal prostate development, prostates were harvested from p1–p21 animals. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed in PBS, and incubated in 1 mg/ml X-gal stain overnight at 37° C. Tissues were dehydrated in graded isopropanol solutions, pre-infiltrated in a paraffin:isopropanol (1:1) solution, infiltrated in paraffin, and embedded in paraffin wax. 6 µm sections of paraffin-embedded tissues were cut and mounted on Superfrost-plus microscope slides (Fisher). Sections were dewaxed in CitriSolv and rehydrated in a series of graded alcohols and PBS. Sections were stained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in graded alcohol solutions, and mounted in Permount.

Urogenital sinus microdissection, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR

Embryos of CD-1 mice (Charles River) were obtained at embryonic day 16.5 and the urogenital sinuses were dissected into Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS) at 4°C. The urogenital sinus mesenchyme and epithelium were separated by digestion with 1% trypsin in HBSS for 90 minutes at 4°C followed by manual dissection. Tissues were homogenized in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription and real-time RT-PCR reactions were conducted as previously described (Thielen et al., 2007) on 1µg of DNAse-treated total RNA. Relative expression values were calculated as 2−dCt where dCt = the experimental gene Ct value minus the control gene Ct value.

Generation of PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice

A full-length human SFRP1 cDNA (Finch et al., 1997) was cloned into a plasmid downstream of the ARR2PB version of the rat probasin promoter (Zhang et al., 2000). The transgenic fragment was purified by cesium chloride gradient and isolated from the plasmid backbone by restriction enzyme digestion and gel electrophoresis. The purified transgene was microinjected into the pronuclei of single-celled FVB/N embryos by the University of Minnesota Mouse Genetics Laboratory to establish founder lines.

Histology and immunostaining

Prostates were dissected into 4°C PBS. Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin wax. Using a microtome, 6 µm sections of paraffin-embedded tissues were cut and mounted on Superfrost-plus microscope slides (Fisher). Sections were dewaxed in CitriSolv and rehydrated in a series of graded alcohols and PBS. For histological analysis, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, dehydrated in graded alcohol solutions, and mounted in Permount. For immunostaining, sections were boiled 30 minutes in Antigen Unmasking Solution according to manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked in 3% hydrogen peroxide and non-specific binding was blocked with 2.5% sheep serum in PBS. All of the following steps used 2.5% sheep serum as a dilutent or an M.O.M. kit according to manufacturer’s instructions for antibodies raised in mice (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Mouse monoclonal anti-Ki67 antibody was used at a 1:100 dilution (Novocastra). After washing in PBT (pH 7.4, 138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.1% Tween 20), sections were incubated in biotinylated species-specific anti-IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) at a 1:500 dilution and washed in PBT. Tissues were incubated in an avidin-HRP complex according to manufacturer’s instructions (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Inc.), washed in PBT, rinsed in PBS, and developed 1–20 minutes using 3, 3”-diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide according to manufacturer’s instructions (DAB substrate kit; Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Sections were rinsed in water, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in graded alcohol solutions, and mounted in Permount. Control sections containing no primary antibody were processed in parallel. Labeling indexes were calculated by counting the number of positively stained epithelial cells in a minimum total of 500 cells.

Protein extractions

Cells were collected, washed in PBS, and pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 rpm in a tabletop centrifuge. The supernatant was aspirated and the cells were resuspended in Iso-Hi buffer consisting of 10mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% NP-40 to lyse the cell membrane leaving the nuclei intact. The cell suspension was incubated on ice and processed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm to pellet the nuclei. The cytoplasmic fraction was separated from the pelleted nuclei. Nuclei were resuspended and lysed in a high salt buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM EGTA. Total proteins were extracted using a modified RIPAs buffer containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors.

Western Blotting

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electro-blotted to an Immobilon membrane (Millipore). Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 1% non-fat milk powder (Fig. 1) or 1% BSA (Fig. 7, Fig. 8) in TBS (pH 7.4,0.9% NaCl, 20mM Tris HCl). Membranes were incubated in primary rabbit polyclonal anti-SFRP1 (Fig. 1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat polyclonal anti-SFRP1 (Fig. 7, R&D Systems), rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphorylated-JNK (#9251) or anti-phosphorylated-CamKII (#3361) antibody diluted to 1:1000 overnight at 4°C (Cell Signaling Technology). After washing in TBS containing 1% Tween-20 (TBST), membranes were incubated in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories) at a 1:10,000 dilution, washed in TBST, and incubated in an avidin-HRP complex according to manufacturer’s instructions (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Membranes were washed in TBST, rinsed in TBS, and incubated 5 minutes in an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Bio-Rad) before exposing to film. Membranes were rinsed and subsequently re-blotted with anti-actin (Santa Cruz), anti-JNK (#9252 Cell Signaling Technologies) or anti-CamKII (#3362 Cell Signaling Technologies) as respective loading controls. Activation of the JNK or CamKII pathway was calculated by normalizing the amount of phosphorylated protein to the amount of total protein with the aid of the Bio-Rad Molecular Analyst software’s Densitometer program. Four independent protein extracts were obtained and analyzed.

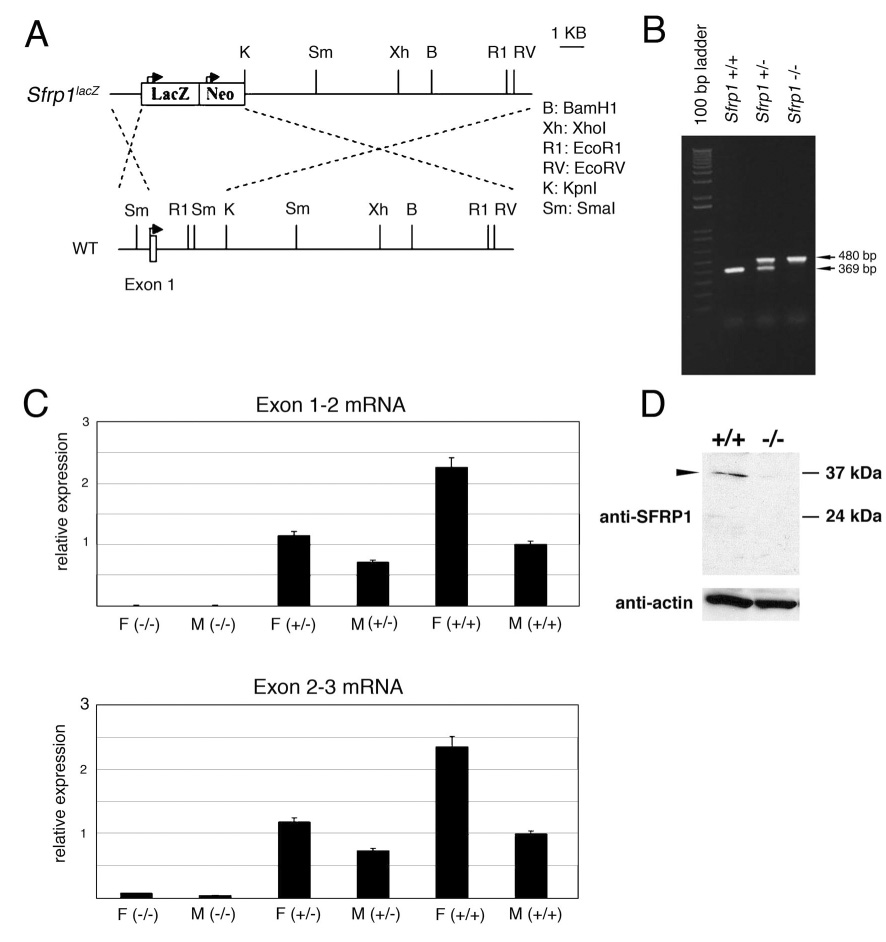

Figure 1. Creation of an Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele that is null for Sfrp1 function.

Sequence immediately downstream of the Sfrp1 start codon in exon 1 and upstream of the KpnI site in intron 1 was replaced with a LacZ/Neo cassette using homologous recombination in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells. A schematic diagram of the wild type (WT) and Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele (Sfrp1lacZ) shows the genomic structure of the knock-in allele (A). The locations of exon 1 and restriction sites in the modified region of Sfrp1 are indicated. ES cells harboring the Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele were used to generate chimeric founder mice that passed the allele to their progeny. The progeny from intercrossing Sfrp1lacZ heterozygous mice were genotyped using a multiplex PCR system in which wild type primers amplified a 369 bp sequence from exon 1 and mutant-specific primers produced an amplicon of 480 bp from the LacZ-Neo insert. Genotyping cross progeny identified all possible genotypic classes among viable cross progeny including wild type (Sfrp1 +/+), heterozygous (Sfrp1 +/−), and homozygous mutant (Sfrp1 −/−) progeny (B). RNA was isolated from kidneys of female (F) and male (M) cross progeny and real time RT-PCR was performed to determine relative expression levels of Sfrp1 among the 3 genotypic classes with the transcript for Tata binding protein serving as an internal control. Homozygous Sfrp1lacZ mice (−/−) lacked Sfrp1 transcripts containing sequence from exons 1 and 2, consistent with the removal of exon 1 by homologous recombination (C, upper graph). Sfrp1 primers corresponding to exons 2 and 3 which were not removed by homologous recombination were also used in real time RT-PCR experiments. There was a dramatically reduced level of RNA containing exon 2 and 3 sequence in homozygous Sfrp1lacZ mice (C, lower graph). Immuno-blots with an anti-SFRP1 antibody confirmed the presence of SFRP1 protein in extracts from the male reproductive tract glands (prostate + seminal vesicles) of wild type (+/+) but not homozygous Sfrp1lacZ mutant (−/−) mice (D, arrowhead in upper panel). An anti-actin antibody was used as a loading control for the immuno-blot (D, lower panel).

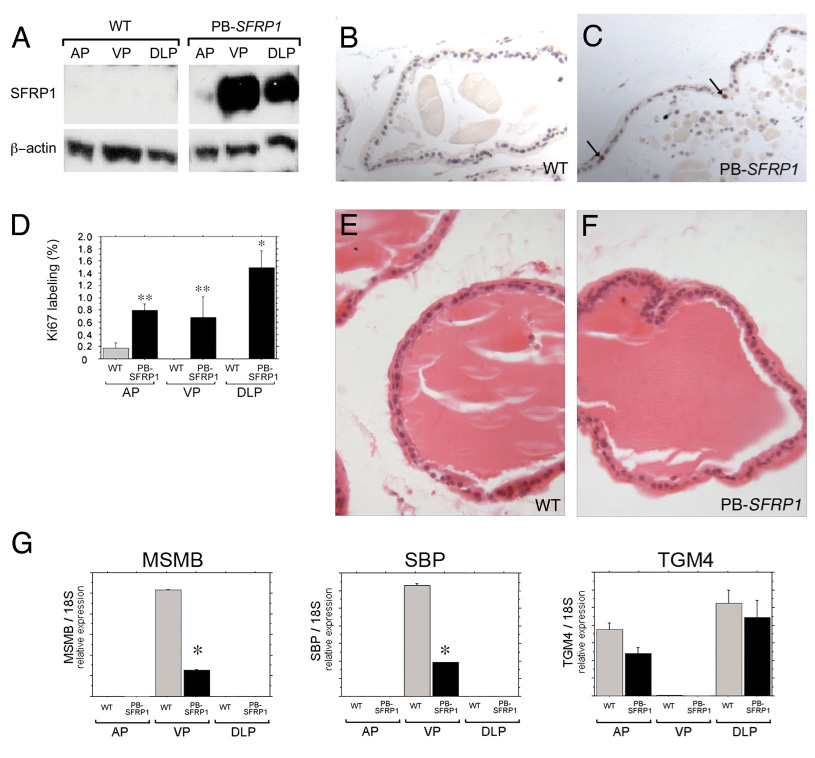

Figure 7. Forced expression of Sfrp1 in the adult prostate induces proliferation and suppresses secretory gene expression.

To further clarify the potential role of Sfrp1 as a local regulator of proliferation and gene expression in the prostate, a transgenic model (PB-SFRP1 mice) was developed to over-express an Sfrp1 cDNA specifically in the prostate under control of the ARR2PB promoter (Zhang et al., 2000). Immuno-blots with an anti-SFRP1 antibody confirmed robust over-expression of SFRP1 in the VP and DLP (A). Longer exposures of immuno-blots also confirmed over-expression in the AP (data not shown). In the adult prostate (5 months of age shown), wild type prostates exhibited almost no Ki67 positive cells (B) while a dramatic increase in the number of Ki67 positive cells was observed in PB-SFRP1 prostates (C,D examples indicated by the arrows in C). Although PB-SFRP1 mice had increased proliferation in the adult prostate, the histology of the prostates in PB-SFRP1 mice remained normal [compare the hematoxylin and eosin stained 1 year old wild type dorsolateral prostate (E) to the 1 year old PB-SFRP1 dorsolateral prostate (F)] Expression of secretory genes was also examined in PB-SFRP1 animals relative to littermate controls (G, data from 1 year old transgenic and control mice shown). Msmb expression and Sbp expression were decreased in the ventral prostates of PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice. A similar trend of decreased Tgm4 expression was observed in both the anterior and dorsolateral prostates of PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice. However, the differences in expression for Tgm4 between controls and PB-SFRP1 animals did not reach statistical significance. Statistically significant differences from ANOVA with least significant post hoc analysis are indicated on the graphs (** P ≤ 0.05, * P ≤ 0.0001).

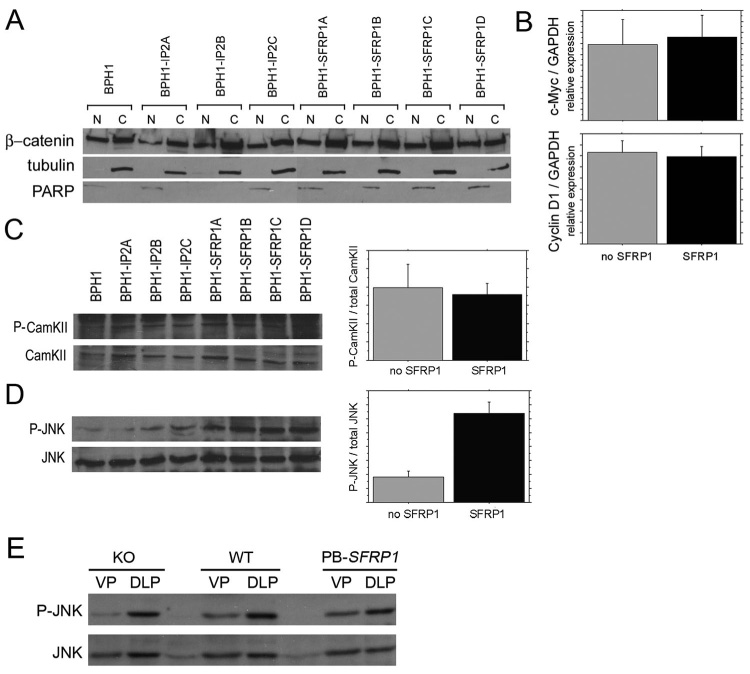

Figure 8. SFRP1 over-expression induces a non-canonical WNT signaling pathway.

Non-tumorigenic prostatic epithelial BPH1 cells were stably transfected with a vector expressing a human SFRP1 cDNA or with an empty vector to create a series of derivative cell lines including 3 derivative BPH1 cell lines stably transfected with an empty vector (BPH1-IP2A, BPH1-IP2B, BPH1-IP2C), and 4 deriviative BPH1 cell lines stably transfected with an SFRP1 expression cassette (BPH1-SFRP1A, BPH1-SFRP1B, BPH1-SFRP1C, BPH1-SFRP1D). (A) Nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) protein fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin. No change in β-catenin localization was detected. Immunoblots for nuclear-specific PARP and cytoplasmic specific α/β-tubulin were used as controls for the quality of protein fractions. (B) Real time RT-PCR was used to look at transcriptional activation of β-catenin target genes c-Myc or CyclinD1 with no changes detected. Whole cell extracts were also subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for activation of non-canonical Wnt pathways. No change in CamKII phosphorylation (P-CamKII) was detected in cells that over-expressed SFRP1 (C). A 3-fold increase in phosphorylated JNK (P-JNK) was detected in cells that over-expressed SFRP1 when compared to cells harboring empty vectors or the parental BPH1 cells (D). Immunoblots were quantified by densitometry and activation was measured as a ratio of phosphorylated protein over total protein. The increase in P-JNK in response to SFRP1 over-expression was statistically significant (* P ≤ 0.0001). (E) Immunoblots also detected the presence of P-JNK in the prostates of Sfrp1 null (KO), wild type (WT), and PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice (data shown is from 12 week old mice).

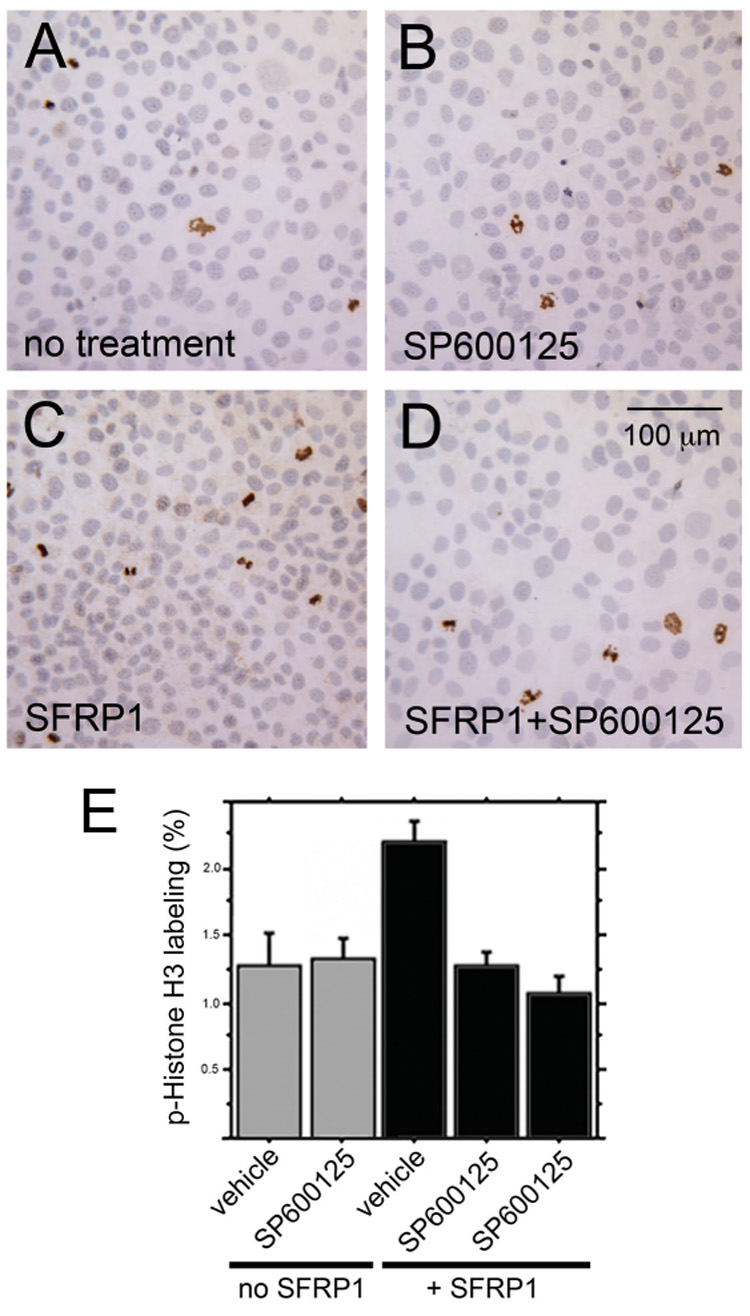

JNK inhibitor studies

SFRP1-expressing and empty vector harboring BPH1 cell lines were generated as previously described (Joesting et al., 2005). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (#22400 Gibco) containing 25 mmol/L HEPES, L-glutamine, 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, 10 units penicillin, 10µg/mL streptomycin, 25 µg/mL amphotecirin, and 1 × 10−8 mol/L testosterone. Cells were grown in a 5% CO2, 37° C incubator. Cells were cultured in 4 well culture slides (#354114 BD Falcon) for 48 hours during treatments in media only, media and 0.1% DMSO (vehicle for SP600125), or media and 10 µmol/L Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 (#PHZ1264 Invitrogen). After 48 hours, cultures were terminated by a 2 minute incubation in 100% ethanol at −20° C and air dried. Cells from terminated cultures were rehydrated with PBS and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 2.5% sheep serum in PBS. Cells were incubated in 7µg/mL primary anti-phospho-histone-H3 antibody overnight at 4°C (#06-570 Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions). Cells were then washed with PBT, and incubated in biotinylated rabbit anti-IgG antibody (BA-1000, Vector Laboratories) at a 1:500 dilution. Cells were washed with PBT and developed using the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) (PK-6100, Vector Laboratories) and 3,3’-diaminobezidine (DAB) substrate (SK-4100) kits according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were rinsed in water, counterstained with hematoxylin and dehydrated via graded ethanol solutions. Control sections containing no primary antibody were processed in parallel. Pictures were taken in triplicate of cells from each SFRP1-overexpressing, empty vector-harboring and from the parental BPH1 cell line grown in each media type. Stained and total cell numbers were counted for each.

RESULTS

Creation of an Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele

To investigate the importance of Sfrp1 in vivo, the mouse Sfrp1 locus was modified using homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells (see Materials and Methods). The resulting mutant allele of Sfrp1 (Sfrp1lacZ allele) had the coding sequences for β-galactosidase inserted into the first exon of the Sfrp1 gene (Fig. 1A). Mice homozygous for this mutant allele were viable (Fig. 1B). In a homozygous state, the Sfrp1lacZ allele was also null for Sfrp1 mRNA expression (Fig. 1C) and SFRP1 protein expression (Fig. 1D), but in the heterozygous state the Sfrp1lacZ allele created no discernable phenotype other than expression of β-galactosidase in the pattern created by endogenous Sfrp1 regulatory elements. A previous study created a different null allele for Sfrp1 and reported that Sfrp1 null mice had changes in osteoblast activity that resulted in altered trabecular bone formation (Bodine et al., 2004). Although we did not undertake an investigation of bone formation in Sfrp1lacZ mice, we did provide Sfrp1lacZ mice to another laboratory conducting studies of bone formation, and they observed similar findings in mice homozygous for the Sfrp1lacZ allele to those reported by Bodine et al. for the other Sfrp1 null allele (Matthew Gillespie, personal communication of unpublished studies).

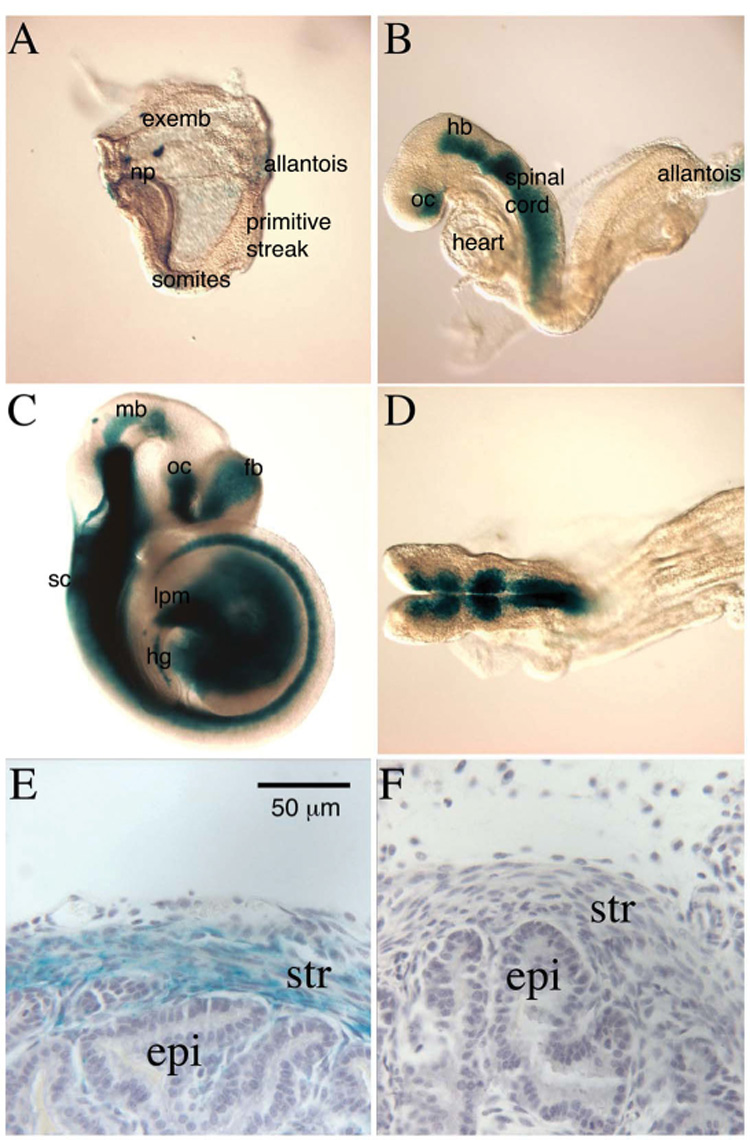

Expression analysis during mouse development using an Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele

Staining Sfrp1lacZ heterozygous embryos for β-galactosidase activity revealed expression patterns created by endogenous Sfrp1 regulatory elements during development. At the 3-somite stage low levels of Sfrp1lacZ gene expression were detectable in the extra-embryonic yolk sac and in the neural plate (Fig. 2A). In the 9-somite stage embryo, Sfrp1lacZ expression was strong in the ventral optic cup, hindbrain, and spinal cord and weak expression was detectable in the extraembryonic allantois. (Fig. 2B,D). Further analysis revealed that Sfrp1lacZ expression was strong in the central nervous system at embryonic day 9.5 and was localized mainly to the ventral regions. β-galactosidase activity was also strong in the lateral plate and the ventral hindgut (Fig. 2C). These sites of expression include anatomical locations that have previously been reported to express Sfrp1 based on in situ hybridization studies (Leimeister et al., 1998) as well as expression at anatomical locations not previously examined for Sfrp1 expression.

Figure 2. Expression analysis using an Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele.

Staining Sfrp1lacZ heterozygous embryos for β-galactosidase activity (blue-green stain) revealed expression patterns created by endogenous Sfrp1 regulatory elements during development. β-galactosidase activity was detected at low levels in the extra-embryonic yolk sac (exemb) and the neural plate (np) in the 3 somite stage embryo (A). At the 9 somite stage, expression was restricted to anterior embryonic regions. Strong β-galactosidase activity was found in the ventral optic cup (oc), hindbrain (hb) and spinal cord, while weak activity was detected in the extraembryonic allantois (B). β-galactosidase was strongly expressed in the CNS at E9.5, and was primarily localized to ventral regions, particularly in the spinal cord (sc) (C). Expression was detected in the midbrain (mb), optic cup (oc) and forebrain (fb). Strong expression was also detected in the lateral plate (lpm) and ventral hindgut (hg), (C). Dorsal view of the same embryo shown in B demonstrating that β-galactosidase was expressed primarily in ventral domains of the hindbrain (D). Whole mount prostates were also stained for β-galactosidase, sectioned, and counter-stained with hematoxylin (purple-grey stain). β-galactosidase staining was observed in the developing mesenchyme/stroma (str) and absent from the developing epithelium (epi) in postnatal day 21 prostates (E). A wild type littermate prostate was also stained and counter-stained as a negative control for any potential background β-galactosidase staining (F). Panel E and F are from the anterior prostate. A similar staining pattern was also observed in the other prostatic lobes.

After confirming that the β-galactosidase reporter recapitulated previously reported expression domains of Sfrp1 expression during embryonic development, the reporter was used to evaluate Sfrp1 expression in the developing prostate gland from postnatal day 1 (p1) to p21. At all stages examined, Sfrp1lacZ expression was observed in the developing prostatic mesenchyme/stroma although expression was not observed in all regions of stroma within the prostate (Fig. 2E and data not shown). At some developmental stages, β-galactosidase activity was also observed in limited regions of the prostatic epithelium of Sfrp1lacZ heterozygous mice, but similar staining was observed in wild type control embryos at the same stages so this staining may or may not have reflected expression patterns generated by endogenous Sfrp1 regulatory elements (data not shown).

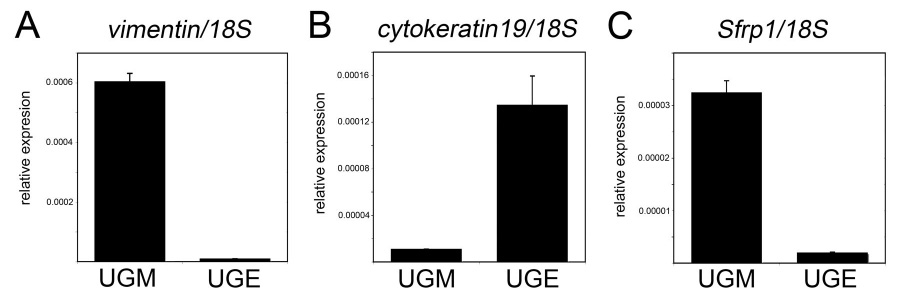

It was somewhat surprising that prostatic expression of the β-galactosidase reporter was predominantly mesenchymal because we had previously observed both strong epithelial and mesenchymal expression in the postnatal day 1 rat prostate by in situ hybridization (Joesting et al., 2005). In the mouse prostate, we did attempt to detect mouse Sfrp1 transcripts at several points during mouse prostatic development by in situ hybridization using antisense RNA experimental probes and sense strand RNA probes as a negative controls. Although several probes were tried, the signal for experimental probes did not significantly exceed the signal for sense control probes suggesting that this technique was not sufficiently sensitive to detect the Sfrp1 transcripts that were detectable in the mouse prostate by RT-PCR (data not shown). As an alternative approach to determine whether the β-galactosidase reporter matched the endogenous expression of Sfrp1, we separated the urogentital sinus mesenchyme (UGM) from the urogenital sinus epithelium (UGE) and examined expression of Sfrp1 and control genes in the UGM and UGE by real-time RT-PCR. As was suggested by the β-galactosidase reporter, expression of the endogenous mouse Sfrp1 gene was predominantly in the developing mesenchyme (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Mouse Sfrp1 is primarily expressed in the prostatic mesenchyme.

Urogenital sinuses from embryonic day 16.5 embryos were microdissected to separate the epithelium from the mesenchyme. Total RNA was isolated from the urogenital sinus mesenchyme (UGM) and urogenital sinus epithelium (UGE) and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Control genes with known mesenchyme-specific and epithelial-specific expression were used evaluate the purity of the microdissected UGM and UGE. As expected, mesenchyme-specific gene vimentin was highly expressed in the UGM relative to the UGE (A). Similarly, epithelial-specific gene cytokeratin19 was highly expressed in the UGE relative to the UGM (B). The expression of Sfrp1 was similar to vimentin with most detectable transcripts in the UGM (C). All graphs depict relative expression as the ratio of the transcript to the 18S ribosomal RNA as a control. Values are the average of 3 samples with the error bars depicting the standard deviation.

Sfrp1 is required for normal levels of prostatic branching morphogenesis

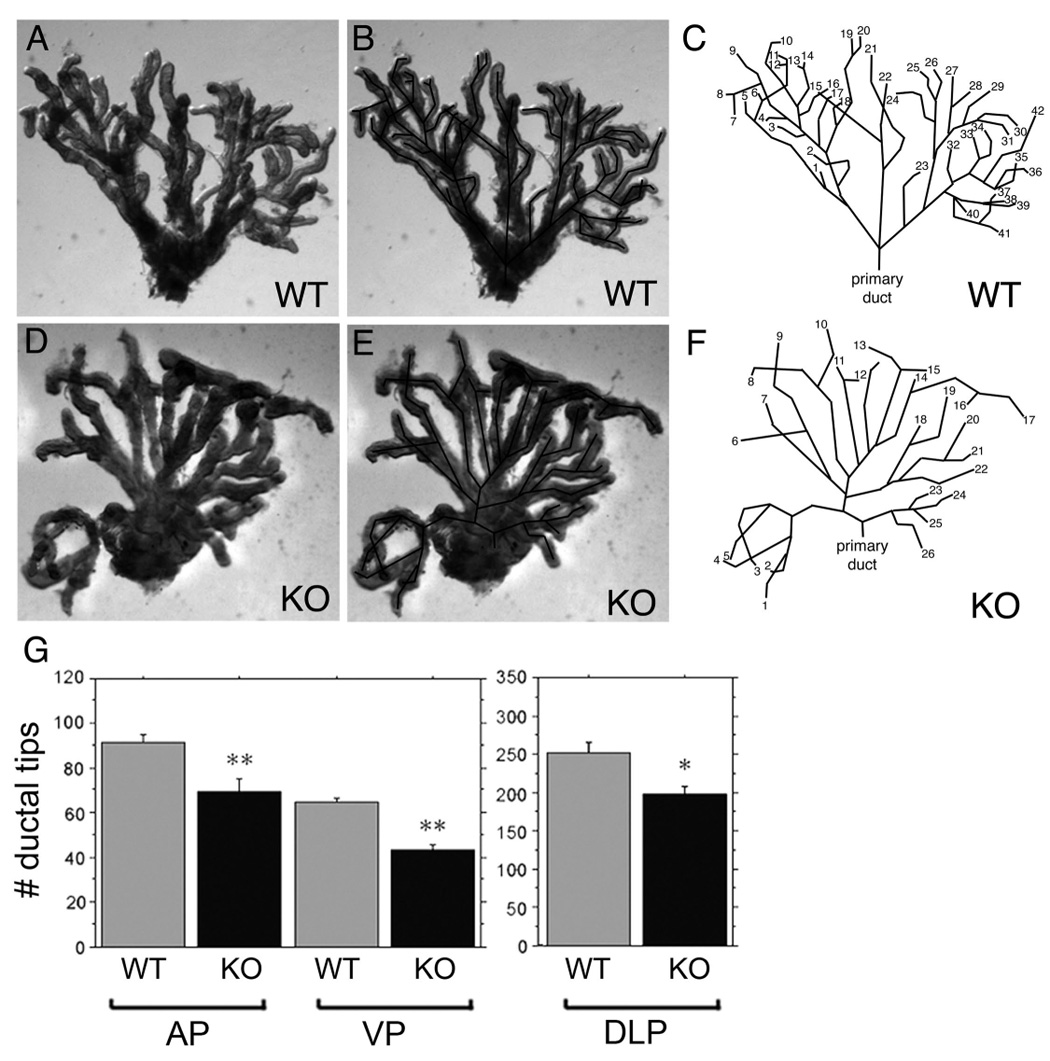

The Sfrp1lacZ allele was also used to evaluate the requirement for Sfrp1 function during prostatic development. Consistent with previous studies that independently created Sfrp1 null alleles in mice (Bodine et al., 2004; Satoh et al., 2006), mice homozygous for the Sfrp1lacZ null allele were born in the expected Mendelian ratio on a mixed genetic background and were viable into adulthood. They were also fertile and lacked obvious external anatomical abnormalities. The previous studies using other strains of Sfrp1 null mice did not report a detailed examination of the prostate gland for developmental defects. As an initial assessment of potential prostatic phenotypes in Sfrp1 null mice, we examined male mice at sexual maturity (5 weeks old). At the level of gross morphology, prostates from Sfrp1 null mice appeared to have normal morphology for all lobes (data not shown). Despite appearing normal at a gross level, micro-dissection revealed a significant reduction in the number of distal tips in each prostatic lobe of the Sfrp1 null mice indicating a reduced amount of developmental branching morphogenesis (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Analysis of prostatic branching morphogenesis in Sfrp1 null mice.

Prostates from both wild type (WT) littermate and Sfrp1 null (KO) animals were micro-dissected at 5 weeks to reveal the ductal branching pattern as previously described (Sugimura et al., 1986). The mouse prostate contains pairs of anterior, dorsolateral, and ventral lobes. Shown are the branching patterns for individual micro-dissected ventral prostate lobes from wild type (A–C) and Sfrp1 null (D–F) animals. Photographs of the micro-dissected lobes are shown with (B,E) and without (A,D) a superimposed trace of the branched structure of the lobe. The traces are also shown separately (C,F) with the ductal tips numbered to illustrate the greater number of ductal tips in the wild type lobe (42 ductal tips) relative to the Sfrp1 null lobe (26 tips). Branching was quantified by counting the number of distal tips in each prostatic lobe under a microscope. The total average number of ductal tips present in the anterior prostate (AP, total for the pair of anterior lobes), ventral prostate (VP, total for the pair of ventral lobes), and the dorsolateral prostate (DLP, total for the pair of dorsolateral lobes) of wild type and Sfrp1 null mice are depicted in bar graphs (G). The Sfrp1 null animals demonstrated a reduction in branching morphogenesis in each of the three prostatic. The decrease in branching was statistically significant (ANOVA with least significant difference post hoc analysis are also indicated ** P ≤ 0.05, * P ≤ 0.0001).

Loss of Sfrp1 delays puberty-associated epithelial cell proliferation

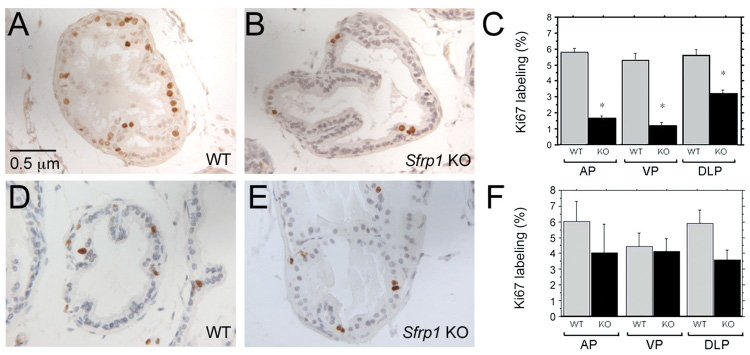

To further examine the potential role of Sfrp1 in the prostate, relative proliferation rates in Sfrp1 null and littermate control prostates were determined using immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect Ki67, a cellular proliferation marker (Scholzen and Gerdes, 2000). At 5 weeks of age, Sfrp1 null prostates had significantly fewer proliferating cells than their wild type littermates (Fig. 5A–C). At 7 weeks of age, Sfrp1 null prostates, although they still had fewer proliferating cells, did not display a significant difference relative to wild type littermate controls (Fig. 5D–F). In animals 10 weeks of age or older, prostatic organ-size was indistinguishable between Sfrp1 null animals and wild type littermate controls. These data suggested that Sfrp1 null animals undergo a developmental delay in which puberty-associated cellular proliferation is temporally deferred, but no long-term deficit in organ growth occurs. Sfrp1 null prostates were also evaluated for changes in apoptosis using a Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase–Mediated Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) assay. TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were extremely rare in wild type control prostates as has previously been reported (Jara et al., 2004), and no increase in apoptotic cells was observed in the prostates of Sfrp1 null mice (data not shown).

Figure 5. Loss of Sfrp1 delays puberty-associated proliferation in the mouse prostate.

Immunostaining for Ki67 was used to examine proliferation in sections of wild type littermate (A, D) and Sfrp1 null (B, E) prostates at 5 weeks of age (A, B) and 7 weeks of age (D, E). Proliferation was quantified by counting the number of luminal epithelial cells expressing Ki67 in a total of 500 or more luminal epithelial cells per prostate lobe of each animal. A minimum of 3 animals was analyzed in each group. At 5 weeks of age, Sfrp1 null prostates had significantly fewer proliferating cells than prostates from wild-type littermate controls (C). At 7 weeks of age the reduction in the number of proliferating cells in Sfrp1 null mice relative to controls was not as great and was not statistically significant (F). Statistically significant differences from ANOVA with least significant post hoc analysis are indicated on the graphs (** P ≤ 0.05, * P ≤ 0.0001).

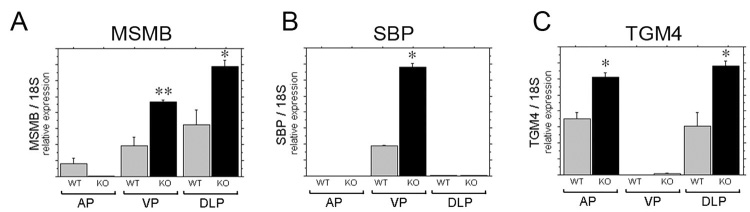

Sfrp1 attenuates expression of genes encoding androgen-regulated secretory proteins

To examine prostatic epithelial cell differentiation in Sfrp1 null mice, three genes encoding prostate-specific secretory proteins with expression that is restricted to specific anatomical lobes of the mouse prostate were examined: β-microsemionoprotein (Msmb) (Ulvsback et al., 1991), spermine binding protein (Sbp) (Chang et al., 1987) and tranglutaminase 4 (Tgm4) (Dubbink et al., 1998). These markers were initially examined in Sfrp1 null and littermate control prostates by in situ hybridization showing that each marker maintained proper lobe-specific localization in the Sfrp1 null prostates (data not shown). However, staining appeared more intense in the Sfrp1 null prostates suggesting a possible increase in transcript levels. To evaluate this possibility in a more quantitative way, real time RT-PCR was performed on RNA from Sfrp1 null prostates. Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that region-specific expression was spatially correct with Msmb detected in the ventral and dorsolateral lobes (Fig. 6A), Sbp detected in the ventral lobe (Fig. 6B), and Tgm4 detected in the anterior and dorsolateral lobes (Fig. 6C). In each case, expression was significantly increased in Sfrp1 null mice relative to wild type littermate controls. These data demonstrated that Sfrp1 negatively regulates expression of these prostate-specific secretory proteins by luminal epithelial cells.

Figure 6. Sfrp1 limits the expression levels of region-specific prostatic secretory proteins.

The genes Msmb, Sbp, and Tgm4 encode androgen-regulated secretory proteins with region-restricted expression by differentiated luminal epithelial cells in the mouse prostate gland (Thielen et al., 2007). Expression of these gene was compared in the Sfrp1 null prostates and wild type littermate controls using real-time RT-PCR and is shown as relative expression normalized to 18s ribosomal RNA. Msmb expression was increased in the ventral and dorsolateral prostates of Sfrp1 null mice (A). Sbp expression was increased in the ventral prostate of Sfrp1 null mice (B). Tgm4 expression was increased in anterior and dorsolateral prostatic lobes of Sfrp1 null mice (C). Statistically significant differences from ANOVA with least significant post hoc analysis are indicated on the graphs (** P ≤ 0.05, * P ≤ 0.0001).

Over-expression of Sfrp1 in the prostate increases epithelial proliferation and decreases expression of secretory genes

Prostatic epithelial proliferation and other cellular behaviors are modulated both by organ intrinsic signaling and by endocrine signaling (Marker et al., 2003). To determine whether Sfrp1 can modulate the behaviors of prostatic epithelial cells by acting directly in the prostate, a prostate-specific Sfrp1 transgenic over-expression model (PB-SFRP1 mice) was created by placing a full-length human SFRP1 cDNA under the control of androgen-responsive, prostatic, epithelial-specific rat probasin promoter (Zhang et al., 2000). This construct was used to make transgenic mice using standard pronuclear injection techniques (see Materials and Methods). Three founder animals were identified that carried the SFRP1 transgene construct. These animals were bred to wild-type FVB/N animals and the resulting progeny were screened by Southern blot to confirm germ line transmission of the transgene (data not shown). Over-expression of SFRP1 in the prostate of the transgenic mice was confirmed by immuno-blotting (Fig. 7A). PB-SFRP1 mice from each transgenic line were also examined for proliferation by IHC. Interestingly, proliferating cells were still detected in the PB-SFRP1 prostates at 5 months of age while the wild type littermate controls exhibited almost no proliferating cells (Fig. 7B–D). These data support the hypothesis that SFRP1 is acts as a pro-proliferation signal by signaling locally in the prostate. Although PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice had increased proliferation in the adult prostate gland, the histology of PB-SFRP1 remained normal at least to 1 year of age (Fig. 7 E,F) with no evidence for an increased incidence of epithelial hyperplasia or dysplasia relative to controls.

Real time RT-PCR analysis for secretory gene expression was also conducted for the PB-SFRP1 transgenic animals. Transgenic animals at 1 year of age demonstrated the same lobe-restricted pattern of expression as 1-year old wild type controls, but each of the transcripts was decreased in expression in the transgenic prostates relative to the controls (Fig. 7G). We did detect a change in the lobar expression pattern for Msmb at the 1-year time point relative to the younger mice (compare Fig. 7A to Fig. 6A), but this change in pattern was seen in both the control and transgenic mice. The effects of the PB-SFRP1 transgene on the expression of Msmb, Sbp, and Tgm4 were also examined in 12 week old mice with similar but less drastic changes including statistically significant decreases in expression for Msmb in the dorsolateral prostate, Sbp in the ventral prostate, and Tgm4 in the dorsolateral prostate (data not shown). PB-SFRP1 transgenic prostates were also evaluated for changes in apoptosis using a TUNEL assay. TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were extremely rare in wild type control prostates as has previously been reported (Jara et al., 2004), and no increase in apoptotic cells was observed in the prostates of PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice (data not shown).

Sfrp1 induces signaling via the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway in prostatic epithelial cells

Proliferation of BPH1 prostatic epithelial cells is stimulated by SFRP1 (Joesting et al., 2005). Thus, this cell line can serve as an in vitro model for at least one of the in vivo responses of prostatic epithelial cells to SFRP1 that were observed in this study. We used BPH1 cells to evaluate the mechanism of SFRP1 action by examining candidate signal transduction pathways that might be affected by SFRP1. As a binding partner of WNT/Fz proteins, SFRP1 could potentially affect one or more of the known WNT signal transduction pathways. To evaluate effects on the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway, changes in the localization of β-catenin and the expression levels of 2 target genes were examined. There was no change in β-catenin localization in cells that over-expressed SFRP1 (Fig. 8A), and the transcript levels for two genes regulated by the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway, c-myc and cyclinD1, were also unchanged (Fig. 8B). At least two non-canonical pathways have also been implicated as mediators of WNT signaling including one pathway that stimulates signaling through phosphorylation of JNK, and a second pathway that has been shown to signal through the phosphorylation of CamKII (Pandur et al., 2002; Widelitz, 2005). These pathways were also evaluated in cells over-expressing SFRP1. There was no change in activation of CamKII (Fig. 8C), but there was a statistically significant 3-fold increase in the activation of JNK in cells that over-expressed SFRP1 (Fig. 8D). This finding suggested that SFRP1 plays a novel role in prostatic epithelial cells by activation of the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway.

The potential activation of JNK in the prostates of wild type, Sfrp1 null, and PB-SFRP1 transgenic mice was also evaluated using immuno-blotting with an anti-phospho-JNK antibody. All three genotypes had detectable levels of activated JNK in the prostate (Fig. 8E). We attempted to use the anti-phospho-JNK antibody in immunohistochemistry experiments to determine if any of the detectable activated JNK was present in prostatic epithelial cells, and to determine if changing the levels of SFRP1 in the prostate altered the activation of JNK in prostatic epithelial cells. Unfortunately, the anti-phospho-JNK antibody did not detect a signal in immunohistochemistry experiments. Thus, we cannot determine at this time whether the responses of JNK to SFRP1 in cultured prostatic epithelial cells are also occurring in the prostatic epithelial cells of SFRP1 transgenic or null mice.

Activation of the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway mediates the pro-proliferative response of prostatic epithelial cells to SFRP1

The importance of JNK activation by SFRP1 was further evaluated by testing the contribution of JNK activation to the SFRP1-induced proliferation of prostatic epithelial cells. The empty vector control and SFRP1 expressing cell lines evaluated for signaling changes (Fig. 8) were also evaluated for proliferation in the presence or absence of SP600125 (Bennett et al., 2001), a small molecule inhibitor of JNK (Fig. 9). Proliferation was evaluated after 48 hours of inhibitor treatment using immunocytochemistry for proliferation-associated marker phospho-(ser10)-histone H3. As previously observed (Joesting et al., 2005), forced expression of SFRP1 caused a statistically significant increase in the proliferation of BPH1 cells (Fig. 9 A,C,E). SP600125 had no effect on the proliferation rate of control cells (Fig. 9 A,B,E). However, SP600125 completely blocked the increased proliferation induced by forced expression of SFRP1 (Fig. 9 C,D,E). These data showed that the SFRP1-induced increase in proliferation required JNK, but JNK played no detectable role in the proliferation of BPH1 cells in the absence of SFRP1.

Figure 9. SFRP1-induced proliferation requires JNK activity.

The same SFRP1-expressing and empty vector control cells evaluated for signaling changes in figure 8 were also examined for changes in proliferation in response to SP600125 (Bennett et al., 2001), a small molecule inhibitor of JNK. Each treatment group was assayed by immunocytochemistry for the proliferation-associated marker phospho-(ser10)-histone H3. Treatments included empty vector cells treated with vehicle only (A), empty vector cells treated with SP600125 (B), SFRP1-expressing cells treated with vehicle only (C), and SFRP1-expressing cells treated with SP600125 (D). Each of the 3 empty vector cell lines and the 4 SFRP1-expressing line was examined. For each cell line and treatment group, the results were quantified by counting the number of phospho-(ser10)-histone H3 positive cells and the total number of cells contained in 3 microscopic fields (a minimum of 1500 total cells were counted for each cell line and treatment group). These data were used to calculate the phospho-(ser10)-histone H3 labeling index as a measure of relative proliferation (E). No change in proliferation was observed in empty vector harboring BPH1 cells when cultured with the JNK inhibitor relative to vehicle controls. A statistically significant (P ≤ 0.0001) 2-fold increase in proliferation was observed in SFRP1-expressing BPH1 cells compared to empty vector cells. This increase in proliferation in response to SFRP1 was completely blocked by the JNK inhibitor such that proliferation of inhibitor-treated SFRP1-expressing cells was statistically indistinguishable from proliferation of empty vector control cells. The results of two independent inhibitor experiments are shown as the two right bars. Error bars in depict the standard error. P-values were calculated using ANOVA with least significant difference post hoc analysis.

DISCUSSION

Our initial interest in the role of SFRP1 in the prostate gland came from an investigation of stromal-to-epithelial signaling during prostate cancer progression. We identified SFRP1 as a candidate paracrine pro-proliferative signal that was over-expressed by fibroblasts isolated from prostatic adenocarcinomas relative to fibroblasts isolated from benign prostates (Joesting et al., 2005). While our study on prostate cancer was in the process of being published, a second study identified SFRP1 as a gene that is epigentically silenced in prostatic epithelial cells during cancer progression (Lodygin et al., 2005). Both our study and the study by Lodygin et al. tested the affects of Sfrp1 on cultured prostatic epithelial cell lines. We observed increased proliferation of the BPH1 cell line in response to Sfrp1 over-expression while Lodygin et al. observed decreased growth of the PC-3 cell line in response to Sfrp1 over-expression. These contrasting experiments using different cell lines suggested that the cellular context had a large impact on the response to SFRP1 in prostatic epithelial cells. These results also created uncertainty as to the potential biological role SFRP1 in the context of normal prostatic development.

Differential response to SFRP1 by different cell lines might be expected because SFRP1 acts by binding WNT ligands and/or Frizzled receptors (Fz) to modulate signaling, and the potential complexity of signaling is high due to the multiple SFRP, WNT, and Fz genes present in mammalian genomes. SFRP1 is one of five SFRPs identified in mice and humans. In addition, mice and humans have 19 different WNT ligands and 10 different frizzled receptors. Evidence suggests that the numerous possible ligand/receptor combinations, including SFRP/WNT and SFRP/Fz interactions, could preferentially and specifically determine target gene activation by inducing different signaling pathways (Rodriguez et al., 2005; Widelitz, 2005). This potential complexity together with the contrasting in vitro results with different prostate cell lines created a need to evaluate the status and functional roles of Sfrp1 in vivo in the normal prostate.

Our previous study used real time RT-PCR to show that the normal in vivo expression of Sfrp1 in the mouse is relatively high during prostatic development and low in the adult prostate (Joesting et al., 2005). We also previously examined Sfrp1 expression in the postnatal day 1 rat ventral prostate by in situ hybridization and observed expression in both the developing mesenchyme and epithelium (Joesting et al., 2005). For the current study, we attempted to detect mouse Sfrp1 transcripts at several points during mouse prostatic development by in situ hybridization using antisense RNA experimental probes and sense strand RNA probes as a negative controls. Although several probes were tried, the signal for experimental probes did not significantly exceed the signal for sense control probes suggesting that this technique was not sufficiently sensitive to detect the Sfrp1 transcripts that were detectable in the mouse prostate by RT-PCR. As an alternative approach, were used the lacZ gene expressed from the Sfrp1lacZ knock-in allele as a reporter for the expression pattern created by endogenous Sfrp1 regulatory elements (Fig. 2). This reporter recapitulated previously described mouse Sfrp1 expression patterns observed by in situ hybridization at several developmental time points (Leimeister et al., 1998). Within the prostate, the reporter was primarily expressed in the developing mesenchyme/stroma across multiple developmental stages from p1 to p21. At some developmental stages, β-galactosidase activity was also observed in limited regions of the prostatic epithelium of Sfrp1lacZ heterozygous mice, but similar staining was observed in wild type control embryos at the same stages. Because we did observe epithelial Sfrp1 transcripts by in situ hybridization in the postnatal day 1 rat ventral prostate (Joesting et al., 2005), some of the epithelial staining may have reflected the activity of the endogenous Sfrp1 regulatory elements, but the background observed in negative controls prevented us from reaching definitive conclusions regarding epithelial expression. Nevertheless, the expression β-galactosidase reporter observed in the developing mesenchyme was much more extensive than the observed epithelial staining, and real-time RT-PCR of separated UGM and UGE confirmed a predominantly mesenchymal expression for Sfrp1 in the mouse prostate (Fig. 3).

To address how normal and ectopic Sfrp1 expression affects the prostate in vivo, we employed both loss- and gain-of-function mouse genetic models. Our analyses of these models demonstrated several developmental defects in the prostates of Sfrp1 null animals. In addition, complementary changes in proliferation and androgen-dependent secretory gene expression were observed in the Sfrp1 null mice and the PB-SFRP1 transgenic over-expression model. Interestingly, the developmental defects in Sfrp1 null mice were primarily epithelial defects although Sfrp1 appears to be mainly expressed in the developing mesenchyme/stroma. This makes SFRP1 another potential mediator of the mesenchyme/stroma-to-epithelial paracrine signals that have been inferred from previous genetic and experimental embryological studies (Marker et al., 2003). Other mesenchymally-expressed paracrine signals that modulate the development of the prostatic epithelium include FGF10 that stimulates growth and branching morphogenesis (Donjacour et al., 2003), and BMP4 and BMP7 that inhibit prostatic branching morphogenesis (Grishina et al., 2005; Lamm et al., 2001). The phenotypes present in Sfrp1 null mice are distinct from the phenotypes reported for Fgf10, Bmp4, or Bmp7 mutants. In particular, the increased expression of several androgen-dependent secretory genes (Fig. 7) in Sfrp1 null mice is a unique phenotype that has not previously been associated with defects in other paracrine signaling pathways in the prostate. Expression of these genes normally occurs as luminal prostatic epithelial cells complete development and differentiate into growth quiescent secretory cells. The phenotypes of prostates with loss and gain of Sfrp1 activity suggest that Sfrp1 antagonizes differentiation while simultaneously promoting proliferation. Other genes including Nkx3.1 are known to have an opposite role in the prostate and promote differentiation while simultaneously limiting proliferation (Bhatia-Gaur et al., 1999).

Although Sfrp1 appears to have some unique roles in prostatic development, it may also cooperate with other paracrine signaling pathways. Little is currently known about the roles of WNT signaling during prostatic development, but data from other branched organs supports the idea that WNT pathways cooperate with other signaling systems. The canonical WNT/β-catenin was shown to act upstream of both FGF and BMP4 signaling as a negative regulator of lung branching morphogenesis (Dean et al., 2005; Shu et al., 2005) although others reported that inhibition of β-catenin signaling by the Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 disrupted branching in the lung (De Langhe et al.). WNT4 signaling was shown to be involved in mammary duct branching during both puberty and pregnancy (Brisken et al., 2000). Our data show that SFRP1, a secreted modulator of WNT signaling, is important for several aspects of prostatic development. One important goal of future research will be to determine how SFRP1 interacts with the FGF and BMP signaling pathways that have previously been implicated as important paracine modulators of prostatic development.

Another interesting finding in this study relates to the role of Sfrp1 in WNT signaling. Almost no data have been published on the potential role of WNT signaling during prostatic development. One recent publication does state that WNT5a, a noncanonical WNT, is a mesenchymal inhibitor of prostatic development, but this assertion was based on currently unpublished data (Pu et al., 2007). More data have been published regarding the potential role of WNT signaling in prostate cancer. Many cancer types exhibit over-activation of the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. Studies of WNT/β-catenin signaling in prostate cancer have reported a variety of results that have been summarized in a recent review by Yardy and Brewster (Yardy and Brewster, 2005), and the importance of changes in canonical WNT signaling in prostate cancer is still debated. Our previous study found that prostatic epithelial cells exposed to recombinant SFRP1 at least transiently down-regulated expression from a reporter plasmid for canonical WNT signaling, and sustained expression of Sfrp1 in the same cells caused a sustained increase in proliferation rate for the cells (Joesting et al., 2005).

In the present study, we sought to further clarify the mechanism of Sfrp1-induced proliferation of prostatic epithelial cells by examining both canonical and non-canonical WNT pathways for sustained changes in response to a continuous Sfrp1 signal. We did not observe sustained changes in the level of nuclear β-catenin or the expression of downstream targets of canonical WNT signaling in response to sustained Sfrp1 over-expression (Fig. 8). There was a significant amount of nuclear β-catenin in the prostatic epithelial cells so β-catenin potentially contributed to proliferation of the cells, but any such role for β-catenin appeared to be independent of regulation by Sfrp1. Cells that over-expressed Sfrp1 were also analyzed for activation of the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway and for activation of the calcium pathway through phosphorylation of CamKII. We found that Sfrp1 over-expression led to a sustained activation of the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway, and that activation of this pathway was essential for Sfrp1-induced proliferation of prostatic epithelial cells. This finding represents a novel function for the non-canonical WNT/JNK pathway as a regulator of prostatic epithelial cells downstream of Sfrp1.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants AG024278 from the NIA/NIH, W81XWH-05-1-053 (proposal PC050617) from the Department of Defense Congressionally Mandated Research Program, and DK069662 from the NIDDK/NIH. We thank Lara Collier and Xin Sun for their help with the manuscript. We thank Robert Matusik for the ARR2PB promoter construct.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bennett BL, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia-Gaur R, et al. Roles for Nkx3.1 in prostate development and cancer. Genes Dev. 1999;13:966–977. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine PV, et al. The Wnt antagonist secreted frizzled-related protein-1 is a negative regulator of trabecular bone formation in adult mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1222–1237. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, et al. Essential function of Wnt-4 in mammary gland development downstream of progesterone signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:650–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TR, et al. Deletion of the steroid-binding domain of the human androgen receptor gene in one family with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: evidence for further genetic heterogeneity in this syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8151–8155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CS, et al. Prostatic spermine-binding protein. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of cDNA, amino acid sequence, and androgenic control of mRNA level. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2826–2831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR. Age-dependent loss of sensitivity of female urogenital sinus to androgenic conditions as a function of the epithelia-stromal interaction in mice. Endocrinology. 1975;97:665–673. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-3-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Lung B. The possible influence of temporal factors in androgenic responsiveness of urogenital tissue recombinants from wild-type and androgen-insensitive (Tfm) mice. J Exp Zool. 1978;205:181–193. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402050203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, et al. Hormonal, cellular, and molecular regulation of normal and neoplastic prostatic development. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;92:221–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Langhe SP, et al. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) reveals that fibronectin is a major target of Wnt signaling in branching morphogenesis of the mouse embryonic lung. Dev Biol. 2005;277:316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean CH, et al. Canonical Wnt signaling negatively regulates branching morphogenesis of the lung and lacrimal gland. Dev Biol. 2005;286:270–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis S, et al. A secreted frizzled related protein, FrzA, selectively associates with Wnt-1 protein and regulates wnt-1 signaling. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 21):3815–3820. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donjacour AA, Cunha GR. Assessment of prostatic protein secretion in tissue recombinants made of urogenital sinus mesenchyme and urothelium from normal or androgen-insensitive mice. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2342–2350. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.7684975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donjacour AA, et al. FGF-10 plays an essential role in the growth of the fetal prostate. Dev Biol. 2003;261:39–54. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbink HJ, et al. The human prostate-specific transglutaminase gene (TGM4): genomic organization, tissue-specific expression, and promoter characterization. Genomics. 1998;51:434–444. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve P, et al. SFRP1 modulates retina cell differentiation through a beta-catenin-independent mechanism. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2471–2481. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch PW, et al. Purification and molecular cloning of a secreted, Frizzled-related antagonist of Wnt action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6770–6775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Hoyos M, et al. Evaluation of SFRP1 as a candidate for human retinal dystrophies. Mol Vis. 2004;10:426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishina IB, et al. BMP7 inhibits branching morphogenesis in the prostate gland and interferes with Notch signaling. Dev Biol. 2005;288:334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward SW, et al. Epithelial development in the rat ventral prostate, anterior prostate and seminal vesicle. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;155:81–93. doi: 10.1159/000147793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He WW, et al. The androgen receptor in the testicular feminized (Tfm) mouse may be a product of internal translation initiation. Receptor. 1994;4:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jara M, et al. Age-induced apoptosis in the male genital tract of the mouse. Reproduction. 2004;127:359–366. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspard B, et al. Expression pattern of mouse sFRP-1 and mWnt-8 gene during heart morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2000;90:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joesting MS, et al. Identification of SFRP1 as a candidate mediator of stromal-to-epithelial signaling in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10423–10430. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm ML, et al. Mesenchymal factor bone morphogenetic protein 4 restricts ductal budding and branching morphogenesis in the developing prostate. Dev Biol. 2001;232:301–314. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimeister C, et al. Developmental expression patterns of mouse sFRP genes encoding members of the secreted frizzled related protein family. Mech Dev. 1998;75:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodygin D, et al. Functional epigenomics identifies genes frequently silenced in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4218–4227. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker PC, et al. Hormonal, cellular, and molecular control of prostatic development. Dev Biol. 2003;253:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal JE. The prostate gland: morphology and pathobiology. Monogr. Urology. 1983;4:3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Olumi AF, et al. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandur P, et al. Increasingly complex: new players enter the Wnt signaling network. Bioessays. 2002;24:881–884. doi: 10.1002/bies.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu Y, et al. Androgen regulation of prostate morphoregulatory gene expression: Fgf10-dependent and -independent pathways. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1697–1706. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner A, et al. A family of secreted proteins contains homology to the cysteine-rich ligand-binding domain of frizzled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risbridger GP, et al. Early prostate development and its association with late-life prostate disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, et al. SFRP1 regulates the growth of retinal ganglion cell axons through the Fz2 receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/nn1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh W, et al. Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 regulate anteroposterior axis elongation and somite segmentation during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2006;133:989–999. doi: 10.1242/dev.02274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu W, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling acts upstream of N-myc, BMP4, and FGF signaling to regulate proximal-distal patterning in the lung. Dev Biol. 2005;283:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura Y, et al. Morphogenesis of ductal networks in the mouse prostate. Biol Reprod. 1986;34:961–971. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod34.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda H, et al. Analysis of prostatic bud induction by brief androgen treatment in the fetal rat urogenital sinus. J Endocrinol. 1986;110:467–470. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1100467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thielen JL, et al. Markers of prostate region-specific epithelial identity define anatomical locations in the mouse prostate that are molecularly similar to human prostate cancers. Differentiation. 2007;75:49–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulvsback M, et al. Assignment of the human gene for beta-microseminoprotein (MSMB) to chromosome 10 and demonstration of related genes in other vertebrates. Genomics. 1991;11:920–924. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren A, et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein-1 binds directly to Wingless and is a biphasic modulator of Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4374–4382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. Cell differentiation lineage in the prostate. Differentiation. 2001;68:270–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting J, et al. Multiple spatially specific enhancers are required to reconstruct the pattern of Hox-2.6 gene expression. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2048–2059. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz R. Wnt signaling through canonical and non-canonical pathways: recent progress. Growth Factors. 2005;23:111–116. doi: 10.1080/08977190500125746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardy GW, Brewster SF. Wnt signalling and prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:119–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, et al. A small composite probasin promoter confers high levels of prostatespecific gene expression through regulation by androgens and glucocorticoids in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4698–4710. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]