ABSTRACT

The transbasal approach offers extradural exposure of the anterior midline skull base transcranially. It can be used to treat a variety of conditions, including trauma, craniofacial deformity, and tumors. This approach has been modified to enhance basal access. This article reviews the principle differences among modifications to the transbasal approach and introduces a new classification scheme. The rationale is to offer a uniform nomenclature to facilitate discussion of these approaches, their indications, and related issues.

Keywords: Frontal fossa, skull base, subcranial, subfrontal, transbasal

Since the introduction of the transbasal approach, which consisted of a low bifrontal craniotomy with extradural exposure, numerous modifications have been made. Numerous terms (n = 60) for these modifications followed (Table 1). Beals and Joganic1 tried to incorporate transbasal approaches in a much broader classification of anterior midline skull base approaches. However, their classification did not prove applicable to the existing literature on such approaches. Moreover, it did not focus on the transbasal approach with extensions. Rather, all major anterior skull base approaches, whether intra- or extracranial, were grouped together. Raso and Gusmäo2 recently suggested a classification system. However, they failed to apply their system to the existing literature to validate its global applicability.

Table 1.

Nomenclature of Transbasal Approaches Reported in the Literature Categorized According to Proposed Classification of Transbasal Approaches

| Transbasal Approach | Level I Transbasal Approach | Level II Transbasal Approach | Level III Transbasal Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transbasal approach13,26,27,28 | Sub-basal approach29 | Extended anterior subcranial approach, type B20 | Telecanthal approach30 |

| Standard subfrontal approach31 | Enlarged transbasal approach32 | Extended transbasal approach17,31 | Radical transbasal approach33 |

| Extradural transbasal approach34 | Supraorbital approach35 | Telecanthal approach30 | Level III transfacial approach1 |

| Frontal transbasal approach36 | Transfrontal approach1 | Extended subcranial approach, type B37 | Transglabellar subcranial approach with extended frontonasal flap38 |

| Transfrontal extradural approach39 | Transbasal approach31 | Transfrontal basal approach40 | Transfrontonasal orbital approach1 |

| Standard transbasal approach41 | Extended frontal approach42 | Transbasal anterior approach40 | Intracranial route A3 procedure5 |

| Traditional transbasal approach43 | Extended subfrontal approach44,45 | Level II transfacial approach1 | – |

| Classic transbasal approach, type 1, subtypes A–C2 | Subcranial approach46 | – | |

| Supraorbital subfrontal approach*,47 | Transglabellar subcranial approach with frontonasal flap38 | – | |

| Bifrontal transbasal approach48 | Extensive subfrontal approach49 | Transfrontonasal approach1 | – |

| Transfrontal approach50 | Extensive transbasal approach51,52 | Subcranial approach46 | – |

| – | Fronto-orbital ridge deposition (FORD) approach26 | Intracranial routes A1–2 procedures7 | – |

| – | Transfrontonaso-orbital approach53 | Anterior craniofacial approach18 | – |

| – | Bifrontal biorbital sphenoethmoidal approach54 | – | – |

| – | Level I transfacial approach1 | – | – |

| – | Subfrontal basal approach†,50 | – | – |

| – | Subfrontal approach55 | – | – |

| – | Trans-sinusal frontal approach56 | – | – |

| – | Versatile frontal sinus approach57 | – | – |

| – | Supraorbital rim approach58 | – | – |

| – | Midline supraorbital approach59 | – | – |

| – | Extended transbasal approach23,43,60,61 | – | – |

| – | Transbasal approach, type II, subtypes A–C2 | – | – |

| – | Transbasal approach, type III, subtypes A–C2 | – | – |

| – | Frontal transbasal approach19 | – | – |

| – | Supraorbital subfrontal approach*,47 | – | – |

Based on the technique described by Obeid and Al-Mefty,47 it is unclear whether an orbital bar osteotomy is applied preventing a clear categorization to transbasal or level I.

Based on technical description by Delfini et al,53 the status of the medial canthal ligaments cannot be defined, preventing a clear categorization to level I or II. However, based on personal communications (Spetzler, Delfini, unpublished data) status of medial canthal ligaments was elucidated.

The absence of a uniformly accepted terminology for the various modifications of the transbasal approach impedes a common understanding of these approaches and inhibits communication and discussion. The many names used to refer to transbasal approaches underscore the potential benefit that a clear and concise classification could offer. The general differences in the modifications consist of various osteotomies of the upper facial structures (orbital bony frame and nasal bone) as well as the status of the canthal ligaments. We therefore highlight the basic differences among these osteotomies added to the original transbasal approach to help unify the existing terminology. We also discuss the unique features of each modification to improve understanding of the modifications and their clinical significance.

PROPOSED CLASSIFICATION OF TRANSBASAL APPROACHES

By definition, all transbasal approaches must be performed via a bicoronal scalp incision, which separates them from anterolateral skull base approaches. Approaches performed through a forehead or extended forehead/facial incision not requiring a bicoronal incision are not considered to be transbasal procedures.

Transbasal approaches consist of an anterior transcranial exposure of the skull base, primarily for extradural pathology. We do not consider frontobasal approaches for intradural lesions to be transbasal procedures (including entirely intradural resection of olfactory groove meningiomas), unless extradural surgery was performed at the same time.

Transbasal Approach

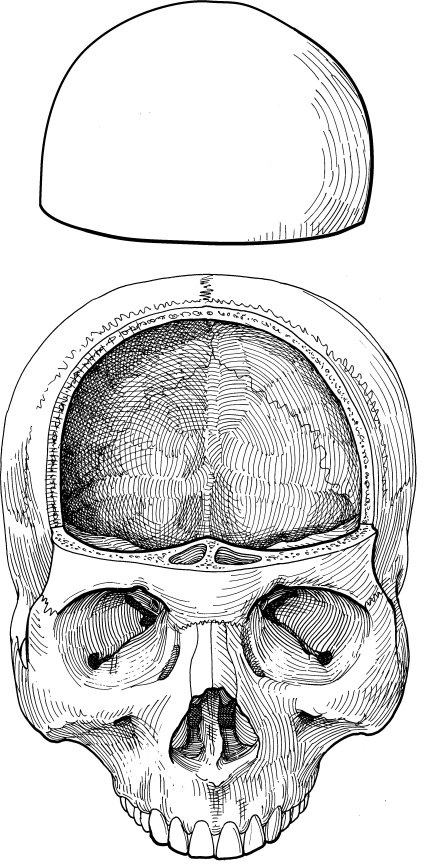

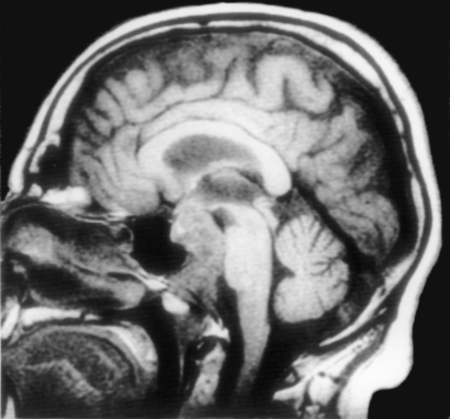

The intracranial entry of a transbasal approach can range from an enlarged bur hole to a wide bifrontal craniotomy. It can be placed unilaterally. However, all these cranial openings should have a frontal location that excludes entry into the temporal fossa. These openings do not include facial osteotomies of the orbital bar or nasion (Fig. 1).

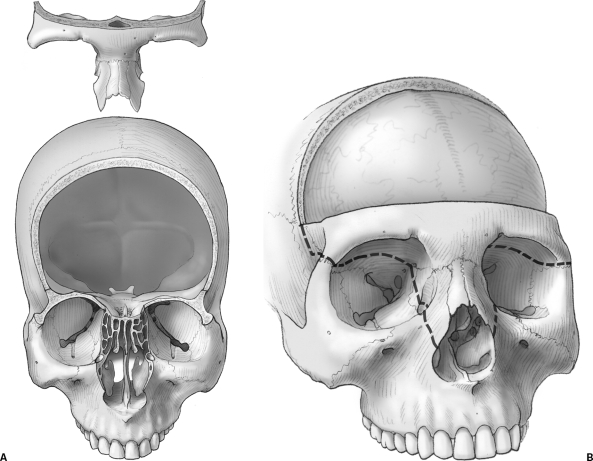

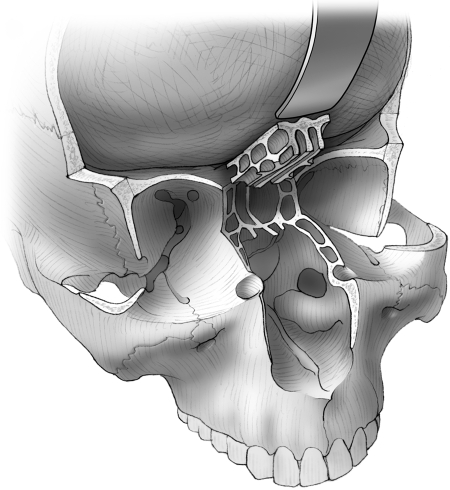

Figure 1.

The transbasal approach consists of a frontal craniotomy without any osteotomies of the orbital bar or nasion. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

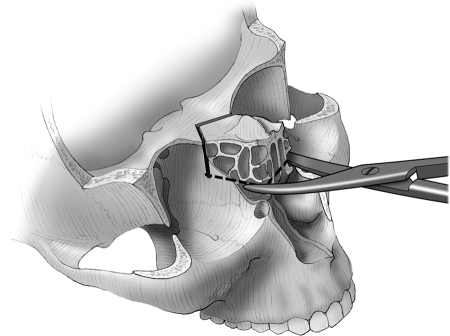

Level I Transbasal Approach

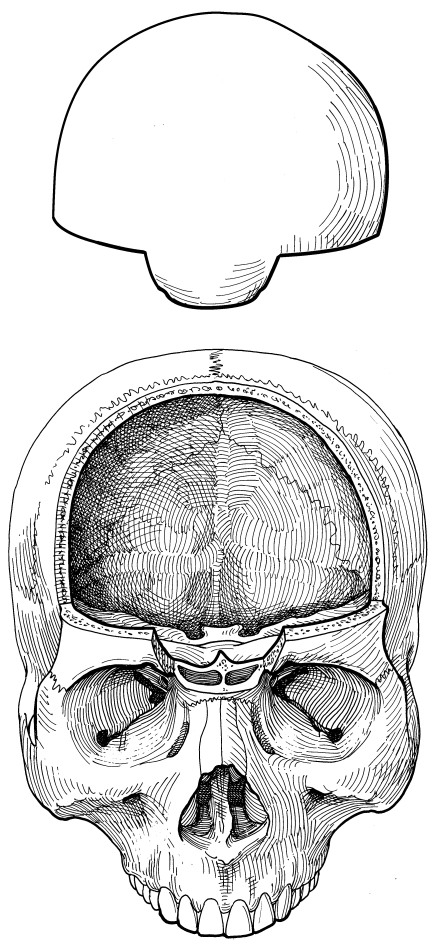

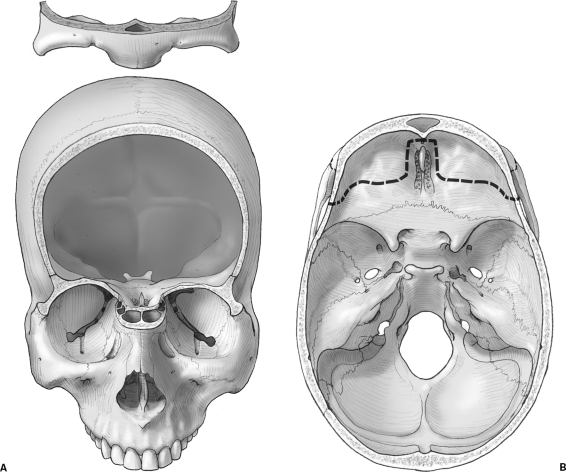

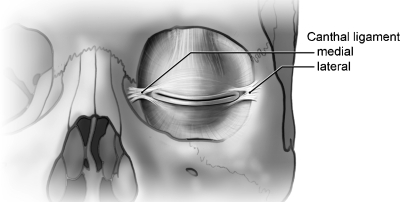

This modification of the transbasal approach consists of the addition of osteotomies along the orbital bar, nasion, or nasal bone to the frontal bone flap (Fig. 2). These osteotomies may be cut as separate fragments from the frontal bone flap, or they can be cut in one piece. The extent of the osteotomy of the orbital bar can include only the nasion (Fig. 2), or it can include the entire orbital bar (Fig. 3). Again, the bone flaps can be unilateral or they can include the orbital roof. The medial canthal ligaments are left intact (Fig. 4). The key to this modification is the presence of an orbital and/or nasal osteotomy without the detachment of the medial canthal ligaments. In particular, osteotomy of the nasal bone without ligamentous detachment is considered here as level I. This definition is a major modification to the classification of Beals and Joganic.1

Figure 2.

The level I transbasal approach adds any orbital bar osteotomy to a frontal craniotomy. The medial canthal ligaments are not violated. Here, the nasion is included in a one-piece fashion with the frontal craniotomy flap. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

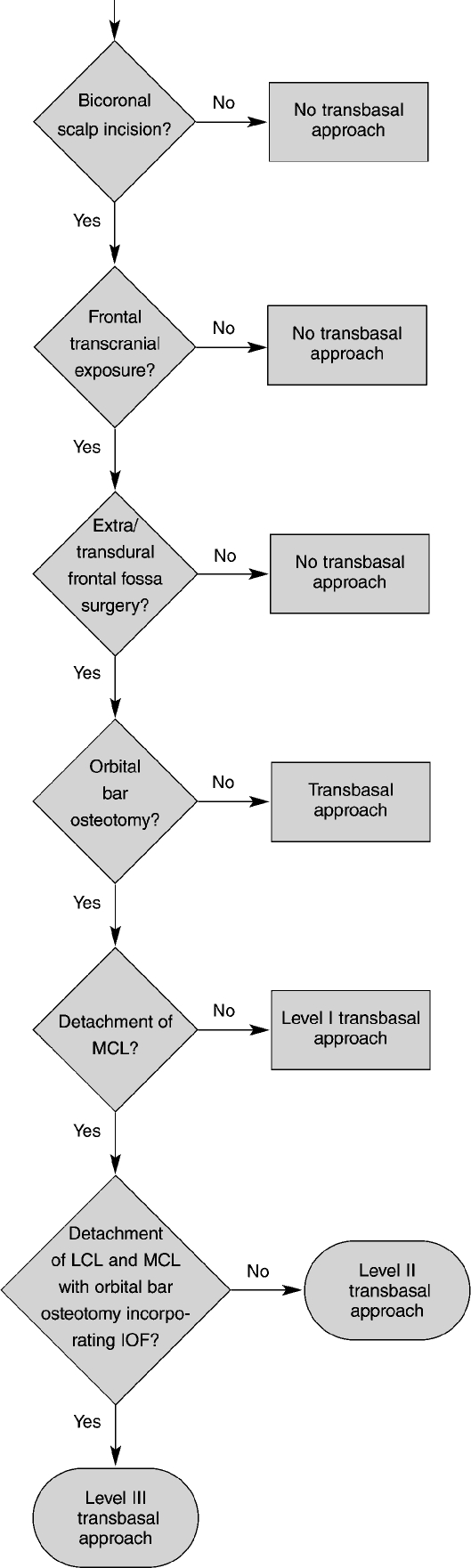

Figure 3.

Here, the extent of orbital osteotomies for a level I transbasal approach varies depending on the surgical need. (A) The entire orbital rim and nasion are included. (B) The osteotomy line is indicated as a dashed line traversing the frontal fossa. (Reprinted from Lawton MT, Beals SP, Joganic EF, Han PP, Spetzler RF. The transfacial approaches to midline skull base lesions: a classification scheme. Operative Techniques in Neurosurgery 1999;2:1–18, with permission from Elsevier.)

Figure 4.

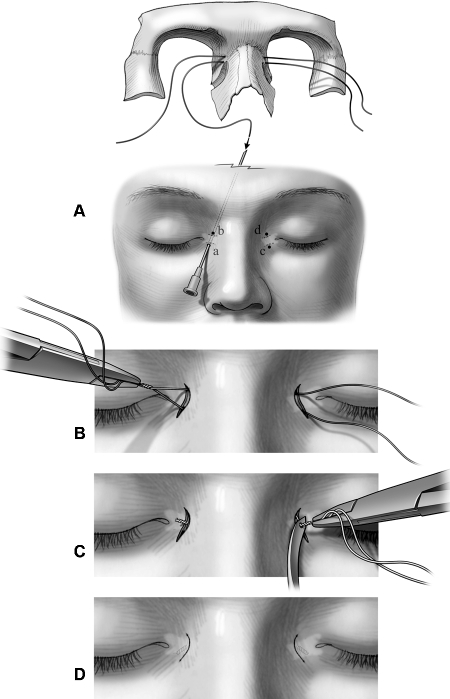

The anatomy of the canthal ligaments is outlined. The status of their integrity is a key component for classification of transbasal approaches. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

Level II Transbasal Approach

A level II transbasal approach combines orbital bar osteotomies along with the uni- or bilateral detachment of the medial canthal ligaments. The orbital bar osteotomies typically include the nasal bone, medial orbital wall, and orbital roof. The lateral orbital wall is not included to a significant extent (Fig. 5). This means that the infraorbital fissure is not incorporated in the osteotomy of the orbital bar fragment. The lateral canthus may or may not be detached. Since, by definition, the medial canthal ligaments are detached, a medial canthopexy is performed at time of reassembly (Fig. 6). Osteotomy of portions of the medial orbital wall places the lacrimal system at risk for violation. Therefore, epiphora can be a postoperative complication associated with this modification of the transbasal approach. Avoiding damage to the lacrimal sac during osteotomy is key to avoiding this problem. If, however, injury occurs, dacryocystorhinostomy or lacrimal stenting may help relieve the symptoms of epiphora. Because the nasal bone is incorporated into the orbital bar, valvular collapse or saddle-nose deformity can occur.

Figure 5.

Here, the extent of naso-orbital osteotomies for a level II transbasal approach varies depending on the surgical need. (A) The entire orbital rim and nasal bone are included. (B) The osteotomy line is indicated as a dashed line traversing the frontal fossa and facial structures. (Reprinted from Lawton MT, Beals SP, Joganic EF, Han PP, Spetzler RF. The transfacial approaches to midline skull base lesions: a classification scheme. Operative Techniques in Neurosurgery 1999;2:1–18, with permission from Elsevier.)

Figure 6.

A medial canthopexy is required after a level II or III transbasal approach because, by definition, the medial canthal ligaments are taken down uni- or bilaterally. (A) Bilateral medial canthopexies are performed using two 28-gauge wires that are passed above and below the medial canthus through puncture holes (labeled as a, b, c, and d) created with an 18-gauge needle. (B) A clamp or needle holder is used to twist ipsilateral wires clockwise about four 360-degree turns. (C) The contralateral wires are then turned four 360-degree turns clockwise while they are placed under tension with a Tessier wire passer awl. (D) Finally, the twisted wire ends are trimmed and buried in the subcutaneous tissue around the medial canthus, and the small semilunar skin incisions are closed with fast-absorbing gut sutures. (Reprinted with permission from Feiz-Erfan I, Han PP, Spetzler RF, et al. The radical transbasal approach for resection of anterior and midline skull base lesions. J Neurosurg 2005;103:485–490.)

Level III Transbasal Approach

This modification is the most extensive form of a transbasal procedure. It resembles a level II transbasal approach with the addition of osteotomies to the lateral orbital wall incorporating the infraorbital fissure (Fig. 7). Both canthal ligaments (medial and lateral) are taken down. This approach also requires a medial canthopexy at the time that the osteotomies are reassembled (Fig. 6). The lacrimal system is at risk and must be protected during osteotomies. Due to the extensive orbital osteotomies and periorbital stripping, the potential risk of enophthalmos is particularly high for this variation.

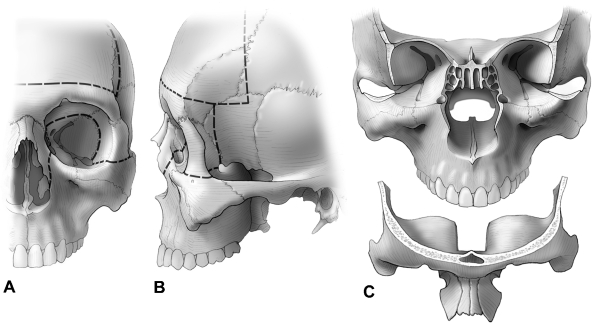

Figure 7.

The (A) frontal and (B) lateral surface views of the skull indicate the osteotomy lines for a level III transbasal approach. (C) The extended orbital bar osteotomy is shown as resected in a bilateral osteotomy. Again, the extent of a level III transbasal approach can be tailored to the pathology. By definition, one medial and one lateral canthus on the same side are taken down with the osteotomy to incorporate at least one infraorbital fissure located on the side of medial canthus detachment. (Reprinted with permission from Feiz-Erfan I, Han PP, Spetzler RF, et al. The radical transbasal approach for resection of anterior and midline skull base lesions. J Neurosurg 2005;103:485–490.)

Application of the Classification

We reviewed the international literature on transbasal surgery and classified approaches reported in the articles (n = 61) based on the above four categories of transbasal approach (Table 2). We found no report of a transbasal procedure that could not be classified according to the preceding criteria. Because all reports were reclassified successfully (Table 2), this classification may provide a system to unify the terminology of transbasal approaches.

Table 2.

Classifications of Transbasal Approaches Reported in the Literature

| Transbasal Approach | Level I Transbasal Approach | Level II Transbasal Approach | Level III Transbasal Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derome13 | Raimondi and Gutierrez62 | Raveh et al20 | Tessier et al5 |

| Honeybul et al31 | Lang et al17 | Fujitsu et al30 | |

| Maroon and Kennerdell50 | |||

| Spetzler and Pappas27 | Jane et al35 | Honeybul et al31 | Beals and Joganic1 |

| Jakumeit63 | Cophignon et al32 | Fliss et al37 | Kellman and Marentette38 |

| Blacklock et al64 | Osguthorpe and Patel29 | Beals and Joganic1 | Feiz-Erfan et al33 |

| George et al26 | Honeybul et al31 | Fujitsu et al30 | Converse et al14 |

| McCutcheon et al65 | Sekhar et al42 | Alvarez-Garijo et al40 | |

| Pompili et al34 | Tzortzidis et al44 | ||

| Arita et al28 | Ross et al66 | Kellman and Marentette38 | |

| Morioka et al36 | Moore et al46 | ||

| Ohnishi et al67 | Shen et al52 | Pinsolle et al68 | |

| Ketcham et al8 | Zhou et al49 | Tessier et al6 | |

| Samii and Draf39 | Kawakami et al51 | Saito et al18 | |

| Unterberger4 | Beals and Joganic1 | Fukuta et al69 | |

| Liu et al41 | George et al26 | ||

| Malecki70 | DeMonte54 | ||

| Kurtsoy et al43 | Chandler and Silva61 | ||

| Raso and Gusmao2 | Delfini et al53,* | ||

| Obeid and Al-Mefty47,† | Sekhar and Wright45 | ||

| Fahlbusch et al48 | Shah et al55 | ||

| Housepian71 | Hallacq et al56 | ||

| Love and Bryar72 | Persing et al57 | ||

| Kaplan et al58 | |||

| Lesoin et al59 | |||

| Terasaka et al23 | |||

| Moore et al46 | |||

| Kurtsoy et al43 | |||

| Chandler et al60 | |||

| Raso and Gusmao2 | |||

| Kawauchi et al19 | |||

| Johns and Kaplan73 | |||

| Obeid and Al-Mefty47,† |

Based on technical description by Delfini et al,53 the status of the medial canthal ligaments cannot be defined, preventing a clear categorization to level I or II. However, based on personal communications (Spetzler, Delfini, unpublished data) status of medial canthal ligaments was elucidated.

Based on the technique described by Obeid and Al-Mefty,47 it is unclear whether an orbital bar osteotomy is applied preventing a clear categorization to transbasal or level I.

DISCUSSION

By definition, the transbasal approach is a transcranial extradural anterior approach to the midline skull base. On November 21, 1936, Dandy3 used a transbasal approach to resect a large frontal meningioma involved with the ethmoid sinus. In 1958 Unterberger4 used this approach to repair traumatic injuries of the anterior skull base. At the time, the concept was new because such injuries were typically approached extracranially. However, using a transcranial approach, Unterberger increased the safety of the operation by affording protection to the intracranial contents. Tessier and associates5,6,7 then used this procedure to correct craniofacial anomalies.

Earlier, Ketcham and colleagues,8 stimulated by the experience of Smith et al,9 discovered that combining a transbasal approach with a transfacial approach in a craniofacial procedure offered safe and effective removal of sinonasal malignancies. Compared with historical controls of patients undergoing transfacial resection, craniofacial resection of sinonasal malignancies improved length of survival. Ketcham et al8 concluded that the intracranial exposure allowed appropriate staging of the transcranial extent of the malignancy and that it allowed successful en bloc resection of the contents of the anterior fossa along with the sinonasal specimen. The major disadvantage was the potential for frontal bone flap infections. The authors tried to prevent such infections by decreasing the size of the frontal bony opening to the size of an extended bur hole.10,11,12

Finally, Derome13 was the first to name this approach the transbasal approach and proposed it for the surgical treatment of tumors involving the anterior midline skull base. According to Derome's description, the transbasal approach was designed to allow neurosurgeons to resect transcranial tumors that invade the frontal fossa. The benefit was to avoid a transfacial procedure and hence to permit craniofacial resection through a craniotomy-only approach. Derome13 further noted that more centrally located structures, such as the clivus, potentially could be reached through a transbasal approach.

To expose the extradural frontal fossa, the transbasal approach always resulted in complete and permanent anosmia because the olfactory fila were sacrificed (Fig. 8). Subsequently, in selected cases, attempts were made to minimize this disadvantage.5,14 In 1993 Spetzler et al15 used a cribriform plate osteotomy (CPO) to preserve olfaction after transbasal approaches. When applied in selected patients, this procedure preserved olfaction more than 90% of the time.16 Other groups also confirmed the feasibility of CPO.17,18,19 Previous attempts to preserve olfaction during transbasal approaches in a few patients20,21,22 had involved unilateral sacrifice of the fila.

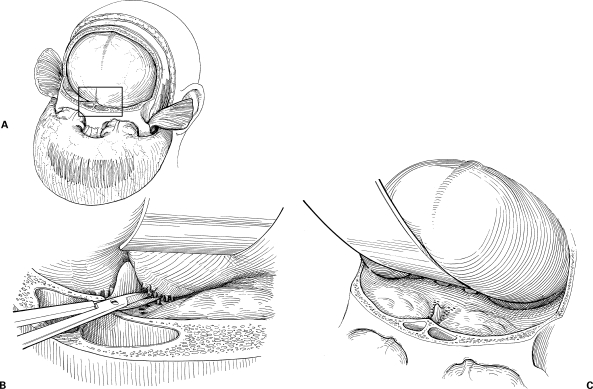

Figure 8.

(A) Traditionally, the transbasal approach (inset, area of interest) requires (B) sacrifice of the olfactory fila. (C) This maneuver allows the frontal dura to be retracted and provides extradural access to the frontal skull base. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

The following indications and rationales for choosing a particular form of transbasal approach represent our opinion based on more than three decades of using different variations of transbasal approaches. Hence, our perspective might not be shared by all experts around the world. However, our recommendations have been crafted especially to help introduce younger colleagues to these approaches and to improve their understanding of the potential differences and options among the various modifications of the transbasal approach.

Transbasal Approach

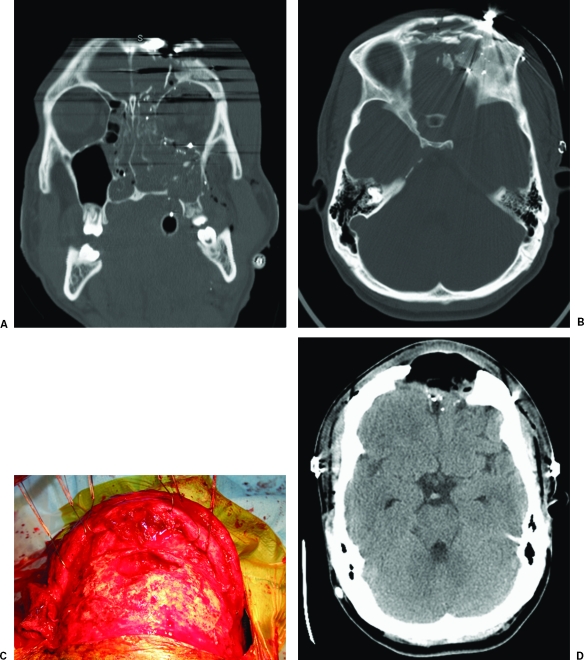

We believe that the transbasal approach is best applied in patients with a traumatic injury to the frontal fossa and sinus who require repair of a cerebrospinal fluid leak (Fig. 9A, B). Avoiding facial osteotomies is potentially important when trying to minimize potential osteomyelitis of a precontaminated traumatic wound. Hence, the cosmetically important orbital bar is at less risk of loss to infection (Fig. 9C, D).

Figure 9.

The transbasal approach is well suited for managing anterior skull base trauma. (A) Coronal and (B) axial bone window computed tomography (CT) scans of the head show multiple craniofacial and skull base fractures associated with an open scalp laceration after direct blunt injury. A transbasal approach was used to repair and close the cerebrospinal fluid leak. Due to the increased risk of infection, no orbital bar osteotomies were included. (C) Six months after surgery, the patient underwent surgical débridement of purulent infection with loss of the frontal bone flap, as seen during the procedure and on a (D) postoperative bone window CT of the head. The initial use of the transbasal approach prevented the functionally and cosmetically important orbital bar from being lost to infection.

Level I Transbasal Approach

This approach provides a more basal trajectory to the frontal fossa than the transbasal approach and hence minimizes brain retraction. It improves access to the central skull base, including the planum sphenoidale, sphenoid sinus, and clivus. Therefore, we recommend this procedure for primary extradural tumor surgery or for large midline meningiomas, where early devascularization of the tumor by cauterization of the ethmoidal arteries aids resection. It can be used in combination with a transfacial approach for en bloc craniofacial resection or as a craniotomy-only form of en bloc craniofacial resection (Fig. 10) if the extracranial tumor is limited. Optimally, extradural clival tumors, including chordomas, can be resected piecemeal via this approach. Cadaveric studies indicate superior exposure of the central skull base compared with the transbasal approach.23 The lateral extent of resection is the internal carotid arteries, optic nerves, and hypoglossal nerves.

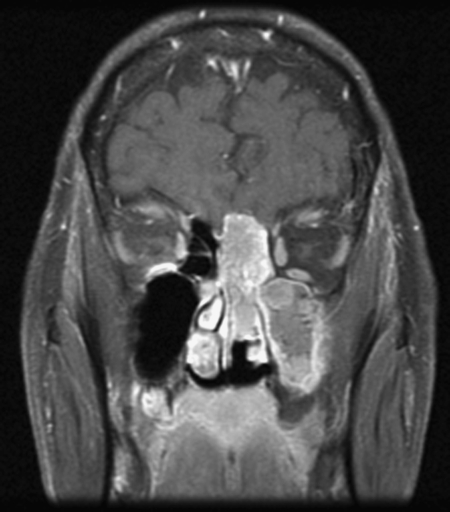

Figure 10.

Contrasted T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows an olfactory neuroblastoma, which was resected through a level I transbasal approach (bifrontal craniotomy with attached one-piece osteotomy of the nasion) combined with a transfacial approach.

Cosmetic deformities of the orbital bar associated with fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 11), encephaloceles (Fig. 12), or synostotic craniofacial suture repair requiring fronto-orbital advancements can also be repaired through this approach.

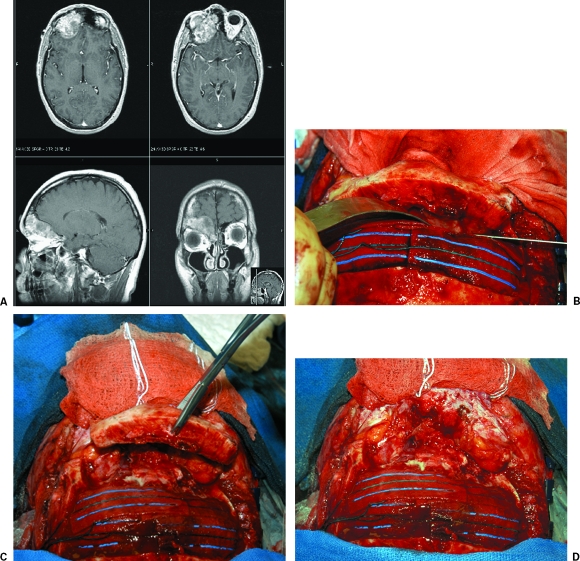

Figure 11.

(A) Magnetic resonance images of the brain show fibrous dysplasia of the orbital bar. (B) Operative photographs show the thickened orbital bar, which has been (C) osteotomized without violation of the medial canthal ligaments (level I transbasal approach). (D) The intraorbital exposure after removal of the orbital bar.

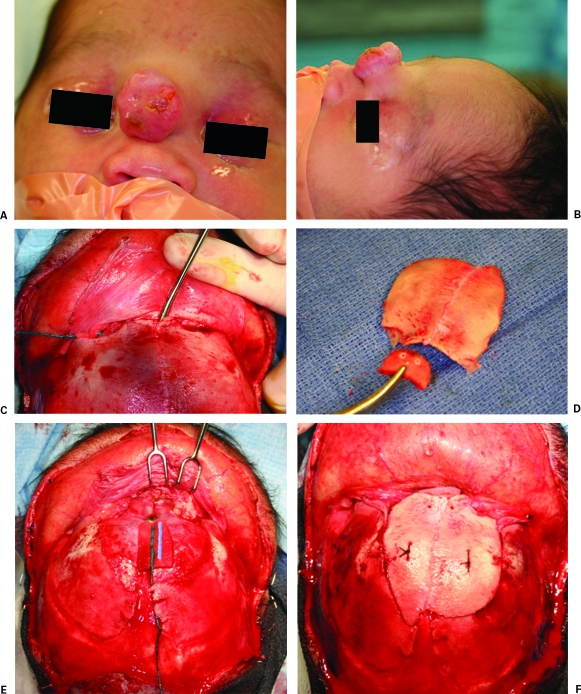

Figure 12.

(A) Anterior and (B) lateral photographs of a baby with a frontal encephalocele. (C) The lesion is outlined with a dissector after a bicoronal scalp incision is performed. (D) The frontal craniotomy flap. A split calvarium graft is used to reconstruct the nasion (level I transbasal approach). (E) After the encephalocele is resected, the bony defect involving the nasion is visible. (F) The defect is reconstructed with the bony fragments seen in (D).

Level II Transbasal Approach

By including the nasal bone and medial orbital wall into the osteotomy of the orbital bar, this modification of the transbasal approach enhances direct exposure of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinus. Therefore, this approach is particularly suited for en bloc craniofacial resection of tumors with limited sinonasal extension, especially if the goal is to avoid a separate transfacial approach. This modification is also suitable for accessing the clivus (Fig. 13). We believe that this level offers slightly more exposure of the clivus compared with the level I transbasal approach.

Figure 13.

Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a clival chordoma that was resected via a level II transbasal approach. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

A second indication for this modification is the application of a CPO to preserve olfaction during transbasal surgeries. To preserve olfaction, at least 1 to 2 cm of olfactory mucosa must be attached to the CPO. Adequate nasal access is needed for the surgeon to maneuver heavy, curved scissors low enough for the mucosal division (Fig. 14). This maneuver can be achieved reliably using the level II modification of the transbasal approach. The procedure includes a nasal bony osteotomy and enhanced access to the nasal cavity.

Figure 14.

The nasal mucosal cuff is cut with heavy, curved scissors 1 to 2 cm below the cribriform plate in an attempt to preserve olfaction during a cribriform plate osteotomy (dashed line). (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

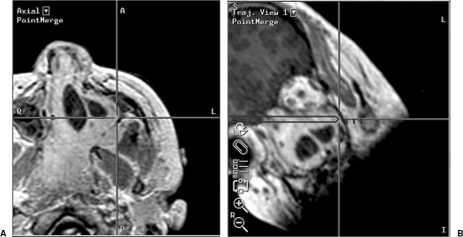

Level III Transbasal Approach

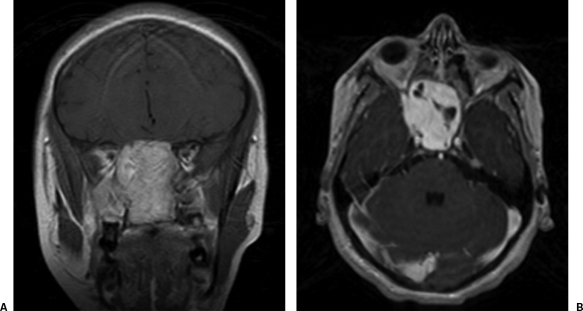

This approach is best for extensive tumors with significant sinonasal involvement (Fig. 15) and for tumors that reach or penetrate one or both medial orbital walls. The addition of a lateral orbital wall osteotomy facilitates retraction of the globes, an otherwise potentially hazardous maneuver that can be associated with visual decline. This modification of the transbasal approach potentially decreases retraction pressure on the globes (Fig. 16), thereby likely protecting the visual apparatus. By maximizing transcranial access to the sinonasal compartment and, in particular, by maximizing transcranial microscopic exposure of the maxillary sinus (Fig. 17), this approach is best indicated for craniotomy-only craniofacial resections, in particular, for benign tumors.24 It also is well suited for avoiding extensive facial skin incisions during a combined craniofacial resection when it is paired with sublabial transfacial approaches for sinonasal pathologies at or below the level of the middle and inferior turbinate.25 Because the nasal bone is incorporated in the orbital bar osteotomy, this variation of the transbasal approach is suitable when a CPO is planned. In such cases, the osteotomized cribriform plate is retracted along with the frontal fossa dura (Fig. 18). The globes are retracted laterally, and tumors of the cranionasal region are widely exposed from a transcranial perspective (Fig. 19).

Figure 15.

Contrasted (A) coronal and (B) axial magnetic resonance images show a large juvenile angiofibroma.

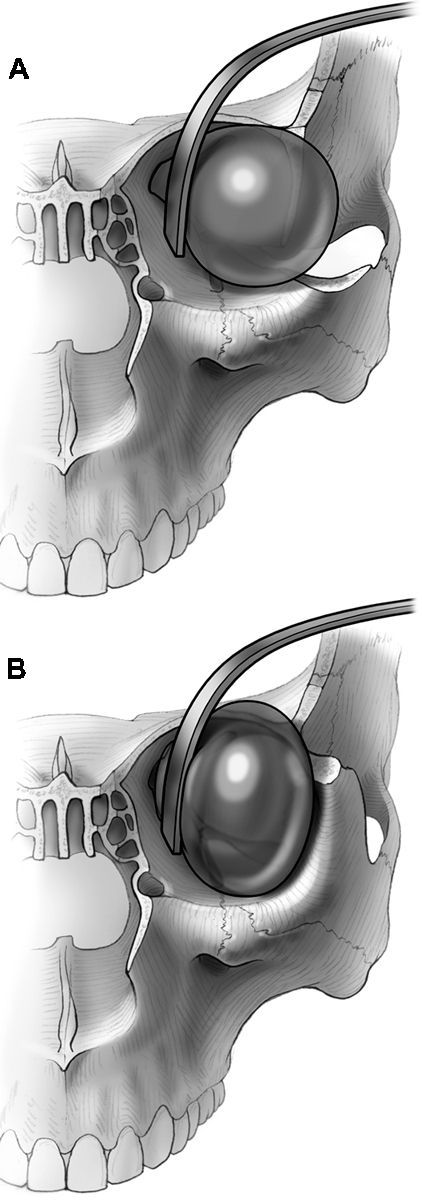

Figure 16.

(A) Osteotomizing the lateral orbital wall down to the infraorbital fissure minimizes retraction pressure on the orbital contents, (B) compared with leaving the lateral orbital wall in place. (Reprinted with permission from Feiz-Erfan I, Han PP, Spetzler RF, et al. The radical transbasal approach for resection of anterior and midline skull base lesions. J Neurosurg 2005;103:485–490.)

Figure 17.

(A) Axial localizing and (B) trajectory neuronavigational views show the microscopic point of focus to be located on the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus. This microscopic view was achieved during craniofacial surgery for resection of a large juvenile angiofibroma via a level III transbasal approach.

Figure 18.

After the cribriform plate osteotomy is completed, the cribriform plate and frontal dura are retracted to allow basal access. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

Figure 19.

(A) After a level III transbasal approach is performed and (B) the juvenile angiofibroma is exposed transcranially, the cribriform plate is retracted along with the frontal dura (a surgical dissector points to the cribriform plate). Lateral retraction of the contents of both orbits maximizes the corridor into the sinonasal cavity. Bilateral osteotomies of the lateral orbital walls minimize retraction pressure on the orbital contents.

CONCLUSIONS

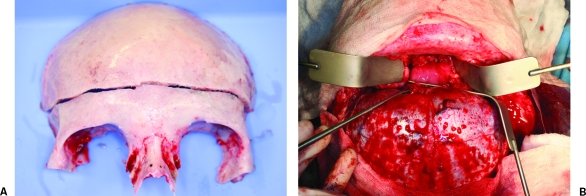

The transbasal approach provides anterior transcranial access to the extradural midline skull base. By including various osteotomies of the orbital bar and nasal bone, the access to sinonasal contents or the central skull base can be increased. We propose a new classification system, which represents a revision and modification of the broader classification scheme of anterior skull base approaches initially reported by Beals and Joganic in 1992.1 The proposed system is focused solely on the transbasal approach and was validated by its retrospective application to the published world literature. This classification outlines clear steps that characterize transbasal procedures (Fig. 20). The goal is to unify the terminology used to describe all transbasal procedures. We hope that this classification will facilitate interinstitutional communication and understanding of these procedures, clarify basic differences and similarities among these modifications, and clarify why and when to use a particular version of the transbasal approach.

Figure 20.

A decision tree outlines key differences and similarities among the transbasal approaches. MCL, medial canthal ligament; LCL, lateral canthal ligament; IOF, inferior orbital fissure. (Reprinted with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ.)

REFERENCES

- Beals S P, Joganic E. Transfacial exposure of anterior cranial fossa and clival tumors. BNI Q. 1992;8:2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Raso J L, Gusmäo S. Transbasal approach to skull base tumors: evaluation and proposal of classification. Surg Neurol. 2006;65(suppl 1):S1:33–S1:37. discussion 1:37–1:38. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandy W E. Orbital Tumors: Results Following the Transcranial Operative Attack. New York: Oskar Piest; 1941.

- Unterberger S. Care of frontobasal wounds [in German] Arch Ohren Nasen Kehlkopfheilkd. 1958;172:463–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier P, Guiot G, Derome P. Orbital hypertelorism: II. Definite treatment of orbital hypertelorism (OR.H.) by craniofacial or by extracranial osteotomies. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;7:39–58. doi: 10.3109/02844317309072417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier P, Guiot G, Rougerie J, Delbet J P, Pastoriza J. Cranio-naso-orbito-facial osteotomies: hypertelorism. [in French] Ann Chir Plast. 1967;12:103–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier P. Orbital hypertelorism: I. Successive surgical attempts. Material and methods. Causes and mechanisms. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;6:135–155. doi: 10.3109/02844317209036714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham A S, Wilkins R H, Buren J M Van, Smith R R. A combined intracranial facial approach to the paranasal sinuses. Am J Surg. 1963;106:698–703. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(63)90387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R R, Klopp C T, Williams J M. Surgical treatment of cancer of the frontal sinus and adjacent areas. Cancer. 1954;7:991–994. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195409)7:5<991::aid-cncr2820070523>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham A S, Hoye R C, Buren J M Van, Johnson R H, Smith R R, Anderson M. Complications of intracranial facial resection for tumors of the paranasal sinuses. Am J Surg. 1966;112:591–596. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(66)90327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buren J M Van, Ommaya A K, Ketcham A S. Ten years' experience with radical combined craniofacial resection of malignant tumors of the paranasal sinuses. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:341–350. doi: 10.3171/jns.1968.28.4.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham A S, Buren J M Van. Tumors of the paranasal sinuses: a therapeutic challenge. Am J Surg. 1985;150:406–413. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(85)90145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derome P J. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editor. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. Boston: Grune & Stratton; 1982. The transbasal approach to tumors invading the base of the skull. pp. 357–379.

- Converse J M, Ransohoff J, Mathews E S, Smith B, Molenaar A. Ocular hypertelorism and pseudohypertelorism: advances in surgical treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;45:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetzler R F, Herman J M, Beals S, Joganic E, Milligan J. Preservation of olfaction in anterior craniofacial approaches. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:48–52. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.1.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz-Erfan I, Han P P, Spetzler R F, et al. Preserving olfactory function in anterior craniofacial surgery through cribriform plate osteotomy applied in selected patients. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:86–93. discussion 86–93. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000163487.94463.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang D A, Honeybul S, Neil-Dwyer G, Evans B T, Weller R O, Gill J. The extended transbasal approach: clinical applications and complications. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999;141:579–585. doi: 10.1007/s007010050346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Takahashi M, Fukuta K, Tachibana E, Yoshida J. Recovery of olfactory function after an anterior craniofacial approach. Skull Base Surg. 1999;9:201–206. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi M, Tomita S, Asari S, Ohmoto T. Preservation of olfaction in frontal transbasal approach. [in Japanese] No Shinkei Geka. 1997;25:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveh J, Turk J B, Ladrach K, et al. Extended anterior subcranial approach for skull base tumors: long term results. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:1002–1010. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.6.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahma B, Gunnlaugsson C, Gala V, Marentette B L, Thompson B G. Treatment of ethmoidal and medial-anterior cranial base pathology using the subcranial approach with attempted preservation of olfaction: outcome in 17 patients [abstract] Skull Base. 2003;13(suppl 1):6. [Google Scholar]

- Browne J D, Mims J W. Preservation of olfaction in anterior skull base surgery. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1317–1322. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200008000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaka S, Day J D, Fukushima T. Extended transbasal approach: anatomy, technique, and indications. Skull Base Surg. 1999;9:177–184. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz-Erfan I, Han P P, Spetzler R F, et al. Experience with the radical transbasal approach in resection of extensive benign anterior skull base tumors [abstract] Skull Base. 2003;13(suppl 1):6. [Google Scholar]

- Feiz-Erfan I, Han P P, Spetzler R F, et al. Exposure of midline cranial base without a facial incision through a combined craniofacial-transfacial procedure. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:28–35. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000144209.03703.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George B, Clemenceau S, Cophignon J, et al. Anterior skull base tumour: the choice between cranial and facial approaches, single and combined procedure—from a series of 78 cases. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1991;53:7–13. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9183-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetzler R F, Pappas C T. Management of anterior skull base tumors. Clin Neurosurg. 1991;37:490–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita N, Mori S, Sano M, et al. Surgical treatment of tumors in the anterior skull base using the transbasal approach. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:379–384. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198903000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osguthorpe J D, Patel S. Craniofacial approaches to sinus malignancy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;28:1239–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujitsu K, Saijoh M, Aoki F, et al. Telecanthal approach for meningiomas in the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:714–719. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeybul S, Neil-Dwyer G, Lang D A, Evans B T, Weller R O, Gill J. The extended transbasal approach: a quantitative anatomical and histological study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999;141:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s007010050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cophignon J, George B, Marchac D, Roux F. Enlarged transbasal approach by mobilization of the medial fronto-orbital ridge. Neurochirurgie. 1983;29:407–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz-Erfan I, Han P P, Spetzler R F, et al. The radical transbasal approach for resection of anterior and midline skull base lesions. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:485–490. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.3.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili A, Caroli F, Iandolo B, Mazzitelli M R, Riccio A. Giant osteoma of the sphenoid sinus reached by an extradural transbasal approach: case report. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:818–821. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198511000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane J A, Park T S, Pobereskin L H, Winn H R, Butler A B. The supraorbital approach: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:537–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka M, Hamada J, Yano S, et al. Frontal skull base surgery combined with endonasal endoscopic sinus surgery. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliss D M, Zucker G, Cohen A, et al. Early outcome and complications of the extended subcranial approach to the anterior skull base. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:153–160. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellman R M, Marentette L. The transglabellar/subcranial approach to the anterior skull base: a review of 72 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:687–690. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.6.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samii M, Draf W. In: Samii M, Draf W, editor. Surgery of the Skull Base: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. Surgery of space-occupying lesions of the anterior skull base. pp. 159–232.

- Alvarez-Garijo J A, Cavadas P, Vila M, Fabregat J, Alvarez A. Craniopharyngioma in children: surgical treatment by a transbasal anterior approach. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14:709–712. doi: 10.1007/s003810050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J K, Decker D, Schaefer S D, et al. Zones of approach for craniofacial resection: minimizing facial incisions for resection of anterior cranial base and paranasal sinus tumors. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1126–1137. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000088802.58956.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar L N, Nanda A, Sen C N, Snyderman C N, Janecka I P. The extended frontal approach to tumors of the anterior, middle, and posterior skull base. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:198–206. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.2.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtsoy A, Menku A, Tucer B, et al. Transbasal approaches: surgical details, pitfalls and avoidances. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27:267–273. doi: 10.1007/s10143-004-0322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzidis F, Bejjani G, Papadas T, et al. Craniofacial osteotomies to facilitate resection of large tumours of the anterior skull base. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996;24:224–229. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(96)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar L N, Wright D C. In: Sekhar LN, deOliveira E, editor. Cranial Microsurgery: Approaches and Techniques. New York: Thieme; 1999. Resection of anterior, middle, and posterior cranial base tumors via the extended subfrontal approach. pp. 82–90.

- Moore C E, Ross D A, Marentette L J. Subcranial approach to tumors of the anterior cranial base: analysis of current and traditional surgical techniques. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:387–390. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid F, Al Mefty O. Recurrence of olfactory groove meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:534–542. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000079484.19821.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlbusch R, Neubauer U, Wigand M, et al. Neuro-rhinosurgical treatment of aesthesioneuroblastoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1989;100:93–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01403592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Guo H, Li S, Ji Y, Huang F. An extensive subfrontal approach to the lesions involving the skull base. Chin Med J (Engl) 1995;108:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroon J C, Kennerdell J S. Microsurgical approach to orbital tumors. Clin Neurosurg. 1979;26:479–489. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/26.cn_suppl_1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Yamanouchi Y, Kubota C, Kawamura Y, Matsumura H. An extensive transbasal approach to frontal skull-base tumors: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1992;74:1011–1013. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Hu J, Hu B, et al. Extensive transbasal approach for removal of tumours in the nasal, sphenoid and clival regions [in Chinese] Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1999;37:35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfini R, Missori P, Iannetti G, Ciappetta P, Cantore G. Mucoceles of the paranasal sinuses with intracranial and intraorbital extension: report of 28 cases. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:901–906. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMonte F. The Chandler/Silva article reviewed. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:923. [Google Scholar]

- Shah J P, Kraus D H, Bilsky M H, Gutin P H, Harrison L H, Strong E W. Craniofacial resection for malignant tumors involving the anterior skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1312–1317. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900120062010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallacq P, Moreau J-J, Fischer G, Béziat J-L. Trans-sinusal frontal approach for olfactory groove meningiomas. Skull Base. 2001;11:35–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persing J A, Jane J A, Levine P A, Cantrell R W. The versatile frontal sinus approach to the floor of the anterior cranial fossa: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:513–516. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.3.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M J, Jane J A, Park T S, Cantrell R W. Supraorbital rim approach to the anterior skull base. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1137–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesoin F, Thomas C E, III, Villette L, Pellerin P, Jomin M. The midline supra-orbital approach, using a large single free bone flap: technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1987;87:86–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02076023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J P, Pelzer H J, Bendok B B, Hunt B H, Salehi S A. Advances in surgical management of malignancies of the cranial base: the extended transbasal approach. J Neurooncol. 2005;73:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-5173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J P, Silva F E. Extended transbasal approach to skull base tumors: technical nuances and review of the literature. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:913–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi A J, Gutierrez F A. A new surgical approach to the treatment of coronal synostosis. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:210–214. doi: 10.3171/jns.1977.46.2.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakumeit H D. Neuroblastoma of the olfactory nerve. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1971;25:99–108. doi: 10.1007/BF01808865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklock J B, Weber R S, Lee Y Y, Goepfert H. Transcranial resection of tumors of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:10–15. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.1.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon I E, Blacklock J B, Weber R S, et al. Anterior transcranial (craniofacial) resection of tumors of the paranasal sinuses: surgical technique and results. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:471–479. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D A, Marentette L J, Moore C E, Switz K L. Craniofacial resection: decreased complication rate with a modified subcranial approach. Skull Base Surg. 1999;9:95–101. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Mori S, Arita N. Primary meningioma of paranasal sinuses treated by the transbasal approach. Surg Neurol. 1987;27:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(87)90296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsolle J, San-Galli F, Siberchicot F, Caix P, Emparanza A, Michelet F X. Modified approach for ethmoid and anterior skull base surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:779–782. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870190091019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuta K, Saito K, Takahashi M, Torii S. Surgical approach to midline skull base tumors with olfactory preservation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:318–325. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199708000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki J. New trends in frontal sinus surgery. Acta Otolaryngol. 1959;50:137–140. doi: 10.3109/00016485909129176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housepian E M. Surgical treatment of unilateral optic nerve gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:604–607. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.31.6.0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love J G, Bryar G E. Transcranial extirpation of orbital tumors. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1966;70:620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns M E, Kaplan M J. Surgical approach to the anterior skull base. Ear Nose Throat J. 1986;65:117–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]