Abstract

Context: The relationship between hormones and bone mineral density (BMD) in men has received considerable attention. However, most studies have been conducted in homogenous populations, and it is not known whether differences in hormones impact racial and ethnic differences in BMD.

Objective: Our objective was to examine associations of testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) with BMD in a racially and ethnically diverse population.

Design: This was a population-based, observational survey.

Participants: A total of 976 Black, Hispanic, and white randomly selected men ages 30–79 yr from the Boston Area Community Health/Bone Survey were included.

Outcome: BMD at the hip, wrist, and spine were calculated.

Results: The mean age of the sample was 46.7 ± 12.4 yr. BMD levels were highest in black men, followed by Hispanic and then white men. Associations between hormones and BMD were consistent across racial and ethnic groups. Total and free testosterone was not correlated with BMD in age- or multivariate-adjusted models. SHBG was inversely correlated with total hip and ultradistal radius BMD after age adjustment, but not with multivariate adjustment for age, lean mass, fat mass, physical activity, self-rated health, and smoking. Total and free estradiol levels were positively and significantly correlated with femoral neck and total hip BMD, even with multivariate adjustment (partial correlations ranged between 0.11 and 0.16). However, estradiol levels failed to account for racial and ethnic differences in hip BMD.

Conclusions: In our diverse population, neither serum total nor free testosterone levels were associated with BMD. Correlations between BMD and estradiol were significant but did not appear to account for any of the observed racial and ethnic differences in BMD. These findings suggest that differences in hormone levels are not a major contributor to the observed differences in BMD between Black, Hispanic, and white men.

In racially and ethnically diverse men between 30 and 79 years of age, bone mineral density is significantly correlated with estradiol levels, but not testosterone levels. Racial and ethnic differences in estradiol do not account for observed racial and ethnic differences in bone mineral density.

Osteoporosis in older men is increasingly recognized as an important health problem (1,2,3,4). Of the 10 million persons older than 50 yr in the United States with osteoporosis, 1–2 million are men, with an additional 8–13 million at increased risk due to low bone mineral density (BMD) (5). A number of studies has now shown substantial racial and ethnic differences in BMD among men (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15); broadly speaking, Black men have on average much higher BMD levels than white and Hispanic men, with smaller differences between the latter two groups.

There are many suspected factors involved in male osteoporosis [e.g. ethnicity, physical activity and body composition, calcium and vitamin D metabolism (4)]. In addition, the potential influence of hormones has garnered substantial attention. Cross-sectional (16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23) and prospective (24,25,26,27) studies conducted in men have demonstrated positive associations between testosterone or estradiol levels and BMD, bone morphology, or bone loss, with the influence of estradiol generally predominating.

There are gaps in our understanding of the role of hormones in skeletal health among aging men. It is not known whether apparent racial and ethnic differences in hormones (28,29,30,31,32,33) impact racial and ethnic disparities in BMD, or whether potential racial and ethnic differences in hormone receptor status (34) might lead to differential associations between hormones and BMD among the racial and ethnic groups. In addition, the clinical relevance of population-level associations between hormones and skeletal health is unclear given that the measurement of hormones in men is not a routine part of clinical practice in the absence of symptomatology. Recent recommendations by The Endocrine Society have emphasized the importance of symptoms in making the diagnosis of androgen deficiency (35). Key unresolved questions include whether the addition of symptoms to biochemical measurements of testosterone actually improves the case definition or predicts bone health better than testosterone measurements alone.

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH)/Bone Survey is a racially and ethnically diverse population-based random sample of men between the ages of 30 and 79 yr. Using data from subjects enrolled in the BACH/Bone Survey, we examined the association between hormones and BMD by racial and ethnic group. In addition, we sought to determine whether adding symptoms to biochemical measures of testosterone differentiates men with respect to BMD.

Subjects and Methods

Study sample

Data were obtained from men enrolled in the BACH/Bone Survey, which is a cross-sectional observational study of skeletal health in 1219 (of 1877 eligible, 65% response rate) randomly selected Black, Hispanic, and white male Boston, MA, residents aged 30–79 yr (6). Persons of other racial/ethnic backgrounds were not enrolled. The BACH/Bone subjects were a subset of 2301 men previously enrolled in the parent BACH Survey; full details of the BACH Survey have been published previously (36). Study protocols were approved by institutional review boards at New England Research Institutes and Boston University School of Medicine. All participants gave written informed consent separately for participation in each study.

Data collection

Full details of the BACH and BACH/Bone Surveys have been previously described (6,36). Briefly, trained staff at New England Research Institutes and the Boston University School of Medicine General Clinical Research Center conducted interviews and measurements for the BACH and BACH/Bone surveys, respectively. Data collection for the BACH Survey generally occurred in participants’ homes. A nonfasting blood sample was collected close to waking time (median time since awakening 3 h 38 min). Serum samples were stored at −80 C until analysis.

Hormone measurements

Testosterone and SHBG were measured at the Children’s Hospital Medical Center Research Laboratories (Boston, MA) by competitive electrochemiluminescence immunoassays on the 2010 Elecsys system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The lower limits of detection for testosterone and SHBG were 2 ng/dl (0.07 nmol/liter) and 3 nmol/liter, respectively. The interassay coefficients of variation for testosterone at concentrations of 24–700 ng/dl (0.83–24.31 nmol/liter) were 7.4–1.7 and 2.4–2.7% for SHBG at concentrations between 25 and 95 nmol/liter. Estradiol was measured by the Mayo Clinic Core Laboratory (Rochester, MN) with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. The lower limit of detection was 12.5 pg/ml (46 pmol/liter). To measure estradiol levels reliably in the low range, estradiol values less than 12.5 pg/ml (46 pmol/liter) were calculated by manual integration of chromatograms. The interassay coefficients of variation for estradiol concentrations 1.25–60 pg/ml (4.6–220 pmol/liter) ranged between 13.4 and 6.0%. Free testosterone and estradiol concentrations were calculated from total testosterone or estradiol and SHBG concentrations using mass action equations (37,38).

Symptoms of androgen deficiency

We have previously published data from male subjects enrolled in the BACH Survey on the prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency (39), operationally defined as the presence of symptoms associated with low testosterone levels in conjunction with low serum testosterone levels. The following symptoms were assessed: low libido, erectile dysfunction (ED), sleep disturbance, depressed mood, lethargy, and low physical performance. The presence of low libido was defined as follows: a response of “low” or “very low” to the question “Over the past 4 weeks, how would you rate your level (degree) of sexual desire or interest?” (1: very high; 2: high; 3: moderate; 4: low; or 5: very low). Men with an international index of erectile function score less than 17 were defined as having ED (40). Items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale(41) included sleep disturbance and depressed mood, and were measured with questions assessing symptoms over the last week, with yes/no responses. Lethargy was assessed by the question “Did you have a lot of energy? (over the past four weeks),” with presence indicated by responses “none of the time” or “some of the time.” Low physical performance was indicated by a score in the lowest quintile of the physical component score of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (42). Subjects were considered symptomatic if they had low libido or ED, or two or more of the following symptoms: sleep disturbance, depressed mood, lethargy, or low physical performance.

BMD measurements

BMD at the proximal femur (femoral neck and total hip), wrist (distal and ultradistal radius), and lumbar spine (L1–L4) was measured by dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using a QDR 4500W densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA). Weekly monitoring of the DXA system revealed no drift during data collection.

Descriptive and covariate data

Age, education, and self-rated health were obtained by self-report, and weight was measured with a digital scale. Total body (nonbone) lean mass and fat mass were obtained from whole body DXA scans using the validated three-compartment model (i.e. bone mineral mass, lean mass, and fat mass) (43). Physical activity level was measured using the validated Physical Activity for the Elderly (PASE) scale (44,45). The number of smoking pack years was calculated by multiplying the number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day by the number of years the subjects smoked.

Statistical methodology

Sampling weights were used to produce statistical estimates that are representative of the Black, Hispanic, and white male population in Boston, MA, between the ages of 30 and 79 yr. Sampling weights account for the design effect of over-sampling of particular age and racial and ethnic groups (46,47). Statistical analyses were conducted using SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) and graphical displays with SAS/GRAPH software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Racial and ethnic group-specific means and cross-sectional age differences [± 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] in the variables of interest were estimated. Partial correlation coefficients (adjusted for age and covariates) were used to estimate the linear relation [judged by visual display with locally weighted linear regression (48)] between BMD and hormones. These analyses were performed both within each racial and ethnic group and then in the cohort as a whole. Multiple linear regression models, with BMD as the outcome and hormone concentration as the predictor, were estimated with adjustments for continuous (age, PASE score, and lean and fat mass) and ordinal (self-rated health and smoking pack years) covariates. Hormones that retained statistical significance in these models were then tested for their ability to explain or account for estimated racial and ethnic differences in BMD in the presence of adjustment for covariates. To determine whether the presence of androgen deficiency symptoms provides a better prediction of BMD beyond that provided by low testosterone levels, we examined mean BMD levels according to symptom presence among men with low total (<300 ng/dl) and free (<5 ng/dl) testosterone levels. The statistical significance of regression effects was determined using Wald hypothesis tests, which were considered statistically significant if null hypotheses could be rejected at the 0.05 level (two-sided).

Analysis samples

Of the 1219 men in the BACH/Bone Survey, 181 did not have their blood drawn, or did not have testosterone or SHBG measured during the BACH Survey. Of the remaining 1038, we excluded 18 men on medications that are known to affect hormone levels (GnRH agonists and antagonists, androgens, estrogens, progestins, 5-α-reductase inhibitors, ketoconazole, danazol, and clomiphene), 32 who were missing femoral neck, total hip, or lumbar spine BMD, and 12 men with extreme outlying values (≥4 sds from mean) of testosterone, SHBG, femoral neck BMD, total hip BMD, or lumbar spine BMD. This left 976 men available as a base for analysis. For estradiol analyses an additional 144 men whose estradiol was not measured were excluded (leaving 832 men).

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the analysis sample by racial and ethnic group. Of the sample, 28% self-identified their racial and ethnic group as Black, whereas 34% were Hispanic, and 38% were white. Black and white men were slightly older and heavier than Hispanic men. Average weight was 87.7 kg. Black and white men had higher lean mass, but white men also had higher fat mass. The sample was relatively healthy, with only 13% reporting fair or poor health but with appreciable variation by racial/ethnicity. Consistent with previously reported results (6), Black men had higher BMD than Hispanic or white men at all skeletal sites, and hip BMD was slightly higher among Hispanic compared with white men.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study sample (n = 976)

| Variable | Mean ± sd or percentagea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Black men (n = 276) | Hispanic men (n = 327) | White men (n = 373) | |

| Age (yr) | 46.5 ± 11.7 | 44.3 ± 10.8 | 47.2 ± 12.9 |

| Education (yr) | 13.4 ± 3.0 | 12.1 ± 5.0 | 16.5 ± 3.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 87.1 ± 16.7 | 82.2 ± 14.3 | 88.8 ± 14.5 |

| General health | |||

| Excellent | 17.1 | 15.3 | 23.6 |

| Very good | 30.9 | 25.5 | 42.4 |

| Good | 38.0 | 35.1 | 23.5 |

| Fair/poor | 14.0 | 24.1 | 10.5 |

| Smoking pack yr | |||

| Never | 41.9 | 50.5 | 46.7 |

| ≤5 pack yr | 26.0 | 25.6 | 18.3 |

| >5 to ≤15 pack yr | 15.7 | 13.5 | 12.3 |

| >15 to ≤30 pack yr | 11.0 | 7.6 | 13.9 |

| ≥30 pack yr | 5.4 | 2.7 | 8.9 |

| PASE score | 204 ± 115 | 190 ± 109 | 188 ± 110 |

| Total body lean mass (kg) | 56.1 ± 8.8 | 52.3 ± 7.3 | 55.5 ± 7.1 |

| Total body fat mass (kg) | 20.2 ± 8.7 | 20.1 ± 7.2 | 22.8 ± 8.2 |

| Femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) | 0.94 ± 0.14 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 0.85 ± 0.13 |

| Total hip BMD (g/cm2) | 1.09 ± 0.15 | 1.03 ± 0.14 | 1.00 ± 0.14 |

| Distal radius BMD (g/cm2) | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.06 |

| Ultradistal radius BMD (g/cm2) | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 0.52 ± 0.07 |

| Lumbar spine BMD (g/cm2) | 1.10 ± 0.15 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 1.03 ± 0.14 |

All estimates are weighted according to sampling design (see Subjects and Methods).

Mean hormone values and their cross-sectional age differences are shown in Table 2. Mean total and free testosterone levels were approximately 5–12% higher in Black compared with Hispanic and white men. As reported previously (49), these differences in means by racial and ethnic group were not significant with one exception: Black men had higher total testosterone than Hispanic men (P = 0.02). SHBG was slightly higher in Black vs. Hispanic men (P = 0.047). Black men had 17 and 10% (both P = 0.04) higher total estradiol levels than Hispanic and white men, respectively, but did not differ with respect to free estradiol. All cross-sectional age differences in hormone levels were statistically equivalent across the racial and ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Means and 10-yr cross-sectional age trends in hormones by racial and ethnic group

| Variable | Black men | Hispanic men | White men |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total testosterone (ng/dl)a | |||

| Mean ± sd | 473.1 ± 207.7 | 420.7 ± 159.8 | 429.6 ± 167.7 |

| Age trend (95% CI) | −18.0 (−42.4, 6.3) | −9.0 (−29.5, 11.4) | −16.0 (−37.2, 5.3) |

| Free testosterone (ng/dl)a | |||

| Mean ± sd | 9.6 ± 3.9 | 9.1 ± 3.6 | 8.9 ± 3.4 |

| Age trend (95% CI) | −1.4 (−1.8, −1.0) | −1.1 (−1.6, −0.6) | −1.1 (−1.5, −0.8) |

| SHBG (nmol/liter) | |||

| Mean ± sd | 36.8 ± 22.5 | 31.4 ± 17.0 | 33.6 ± 16.1 |

| Age trend (95% CI) | 7.7 (5.8, 9.5) | 6.4 (4.7, 8.0) | 5.0 (3.3, 6.7) |

| Total estradiol (pg/ml)b | |||

| Mean ± sd | 25.6 ± 9.9 | 23.0 ± 9.1 | 23.1 ± 9.0 |

| Age trend (95% CI) | 0.5 (−0.8, 1.7) | 0.2 (−1.2, 1.5) | −0.1 (−1.1, 0.9) |

| Free estradiol (pg/ml)b | |||

| Mean ± sd | 0.71 ± 0.26 | 0.67 ± 0.27 | 0.66 ± 0.26 |

| Age trend (95% CI) | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.06 −0.002) |

All estimates are weighted according to sampling design (see Subjects and Methods).

To convert to nmol/liter, multiply values by 0.0347.

To convert to pmol/liter, multiply values by 3.671.

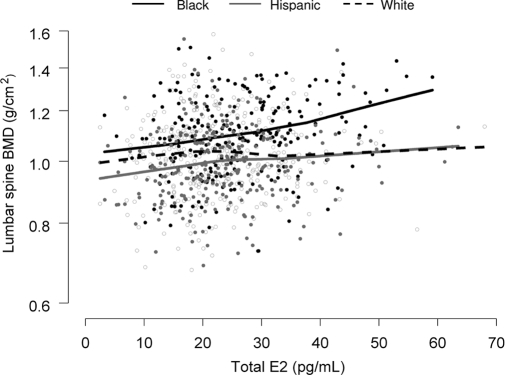

Evidence for racial and ethnic variation in the association between hormone levels and BMD was very weak. We examined 25 interactions (racial and ethnic group × total/free testosterone and estradiol and SHBG for the five skeletal sites) and found only one to be significant (Fig. 1, lumbar spine BMD vs. total estradiol; the P value for the racial and ethnic group × total estradiol interaction = 0.048).

Figure 1.

Lumbar spine BMD (natural log scale) as a function of total estradiol (E2) by racial and ethnic group. Locally weighted linear regression curves (smoothing parameter = 0.9) are shown for each racial and ethnic group. As indicated, there appears to be racial and ethnic variation in the association between BMD and total estradiol, with a stronger association observed particularly among Black men. The P value for the interaction between race and ethnic group × total estradiol was 0.048. However, of 25 interactions tested (racial and ethnic group × total/free testosterone and estradiol and SHBG for the five skeletal sites), this was the only one for which the null hypothesis of no racial and ethnic difference in the association between BMD and hormones could be rejected.

Having found little evidence for variation in associations by racial and ethnic group and in additional analyses not shown, no evidence of nonlinear associations between hormones and BMD, we computed linear correlations between hormone levels and BMD outcomes in the sample overall (Table 3). Neither total nor free testosterone was associated with BMD at any skeletal site in age- or multivariate-adjusted models. SHBG was significantly and inversely associated with total hip and ultradistal radius BMD when adjusted for age, but not when further adjustments were made. Total and free estradiol showed larger positive correlations with BMD outcomes. Correlations between estradiol levels and hip BMD were robust to multivariate adjustment with partial correlation coefficients ranging between 0.11 and 0.16.

Table 3.

Age- and multivariate-adjusted Pearson correlations between BMD and hormones

| BMD variable | Total testosterone | Free testosterone | SHBG | Total estradiol | Free estradiol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted Pearson correlation (bold, P < 0.05) | |||||

| Femoral neck | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| Total hip | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.13 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Distal radius | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Ultradistal radius | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| Lumbar spine | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Multivariate-adjusted Pearson correlation (bold, P < 0.05)a | |||||

| Femoral neck | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| Total hip | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Distal radius | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| Ultradistal radius | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Lumbar spine | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

All estimates weighted according to sampling design (see Subjects and Methods).

Adjusted for the continuous (age, lean mass, fat mass, and physical activity) and ordinal (self-rated health and smoking pack years) variables.

Based on these data, we examined whether total or free estradiol explained or accounted for estimated racial and ethnic differences in hip BMD in the presence of adjustment for covariates. The results, displayed in Table 4, indicated that neither plays a role in racial and ethnic differences in BMD, after adjustment for age, physical activity, smoking status, and general health. This is reflected in the lack of change in percent differences between racial and ethnic groups when comparing model 1 with models 2 and 4. By contrast, as we have noted in a previous publication (50), there is a substantial impact of body composition on racial and ethnic differences in BMD (compare models 2 vs. 3 and 4 vs. 5), particularly in comparisons that involve Hispanic men.

Table 4.

The influence of total and free estradiol on racial and ethnic differences in hip BMD

| Percent difference in BMDa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Black vs. white | Black vs. Hispanic | Hispanic vs. white | |

| Femoral neck BMD | |||

| Model 1 (without estradiol and body composition) | 11.4 | 8.3 | 2.8 |

| Model 2 (with total estradiol; no body composition) | 11.4 | 8.2 | 3.0 |

| Model 3 (with total estradiol and body composition) | 11.2 | 4.6 | 6.4 |

| Model 4 (with free estradiol; no body composition) | 11.6 | 8.5 | 2.9 |

| Model 5 (with free estradiol and body composition) | 11.4 | 4.8 | 6.3 |

| Total hip BMD | |||

| Model 1 (without estradiol and body composition) | 8.9 | 7.2 | 1.6 |

| Model 2 (with total estradiol; no body composition) | 8.8 | 7.1 | 1.6 |

| Model 3 (with total estradiol and body composition) | 8.6 | 3.2 | 5.3 |

| Model 4 (with free estradiol; no body composition) | 9.0 | 7.3 | 1.6 |

| Model 5 (with free estradiol and body composition) | 8.7 | 3.3 | 5.2 |

All estimates weighted according to sampling design (see Subjects and Methods).

All multivariate regression models included physical activity centered at its mean, age centered at 50 yr, and smoking pack years and self-rated health as ordinal variables. Measures of body composition (lean and fat mass) were also centered at their means. As a result, percent differences reported are for hypothetical men with the following characteristics: lean mass (50 kg), fat mass (20 kg), PASE score (175), those who have never smoked and in excellent health, and age (50 yr).

Table 5 shows the percent difference in BMD levels (adjusted for age and total testosterone) among symptomatic men with low testosterone levels compared with asymptomatic men with low testosterone levels. Symptomatic men (i.e. those who would meet the definition of symptomatic androgen deficiency) had 7–9% lower femoral neck (P = 0.12), total hip (P = 0.09), and ultradistal radius (P = 0.15) BMD compared with asymptomatic men.

Table 5.

Adjusted percent difference in mean BMD according to symptom presence/absence among men with low total (<300 ng/dl) and free (<5 ng/dl) testosterone levels

| Skeletal site | Percent difference (95% CI) in BMD, symptoms present (n = 40) vs. symptoms absent (n = 35) |

|---|---|

| Femoral neck | −8.4 (−17.9, 2.3) |

| Total hip | −9.0 (−18.5, 2.3) |

| Distal radius | −0.6 (−4.1, 3.0) |

| Ultradistal radius | −7.4 (−16.7, 2.9) |

| Lumbar spine | −3.8 (−12.9, 6.3) |

Adjusted for age and total testosterone level. All estimates are weighted according to sampling design (see Subjects and Methods).

Discussion

In this random-sample population-based study of 976 racially and ethnically diverse men from Boston, we found that neither total nor free testosterone is associated with BMD, but total and free estradiol is. Nonetheless, despite the strong correlations observed between estradiol and BMD, our data do not support the hypothesis that racial and ethnic differences in estradiol account for racial and ethnic disparities in BMD. In addition, we found no evidence to a support a differential effect of hormones on BMD by racial and ethnic group.

Numerous investigations have focused on the association between hormones and BMD in men. Our data are consistent with findings showing that the effect of estradiol predominates (16,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27). Indeed, the integral role of estradiol in regulating bone metabolism in adult men has also been demonstrated in physiological intervention studies (51,52). Thus, although our data are largely confirmatory, we can now extend this finding to a racially and ethnically diverse population.

At least one previous study has shown that the ratio of estradiol to testosterone is lower in men with osteoporosis, suggesting a role for an impairment of aromatase activity in bone loss (25). In analyses not presented, the age-adjusted correlation between femoral neck BMD and the ratio of estradiol to testosterone was 0.05, a value much smaller than that for total estradiol, and not statistically significant. This indicates that any effect of the ratio of estradiol to testosterone is mediated fully by the estradiol level. We also found no evidence in support of a threshold effect of total or free estradiol, which is consistent with the more rigorous explorations of this issue (24).

Previous studies comparing testosterone levels in different racial and ethnic groups have been in conflict. Whereas some have reported higher testosterone levels among Black compared with white men (28,29,30,32,33), others have reported no racial differences in testosterone concentrations (49,53,54,55,56,57). These discrepancies might be explained by age differences in the study populations because racial and ethnic differences in testosterone levels have generally been observed only in studies of younger males. Thus, serum androgen concentrations early in life might be responsible for the higher peak bone mass observed among Black men (58,59,60). The BACH/Bone study was not designed to assess this possibility.

Data on racial and ethnic differences in estradiol are comparatively rare. Although data from The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men study (30) found no evidence of racial and ethnic differences in estradiol, our data are consistent with those from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which indicate higher estradiol concentrations among Black compared with Hispanic and white men (31). The reasons for these discrepancies are unclear but could be due to study population age differences or differences in the measurement of estradiol, thus making comparisons between studies difficult. These racial and ethnic differences in circulating estrogen concentrations may be due to genetic diversity in aromatase expression or other enzymes in the gonadal steroid production pathway.

Despite the strong and robust association that we observed between estradiol and hip BMD and racial and ethnic differences in estradiol concentrations, our data indicate that circulating estradiol plays a little role in explaining racial and ethnic differences in BMD beyond that which can be attributed to age, physical activity, smoking status, and general health. Thus, it is likely that factors largely unrelated to the influences of gonadal steroids are mediating the well-established racial and ethnic differences in BMD and fracture rates.

We presented novel data on whether average BMD levels differed among men with low testosterone levels according to symptom presence, with a view toward understanding whether the construct of “symptomatic androgen deficiency” or, more specifically, whether the addition of symptoms to biochemical testosterone measurements might improve the prediction of average BMD levels. There was a suggestion that among men with low testosterone levels, those who report symptoms may have lower BMD than men who do not report symptoms. If so, this could indicate that BMD measurement might be considered in men who present with symptomatic androgen deficiency (particularly if other risk factors for osteoporosis are present), but it must be recognized that these data are very limited due to the small number of subjects and the consequent low statistical power.

Limitations to the current study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of these data prohibits estimation of causal relationships. Second, the liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method by which estradiol was measured had limited sensitivity, which forced us to perform manual integration of chromatograms. Finally, the clinical utility of these population-level data remains unclear. Nonetheless, recent work by Fink et al. (24) shows that older men with low testosterone or estradiol levels are at an increased risk for osteoporosis. These limitations must be balanced against the strengths of this study, which include a random, population-based study of a large number of racially and ethnically diverse men across a broad age range, careful control of potential confounding variables, and a statistical modeling strategy aimed at accounting for race and ethnic differences in BMD that is consistent with good statistical practice. In addition, this is the first study to report on the association between BMD and symptomatic androgen deficiency, which is more consistent with what might be observed clinically.

In summary, we find no evidence that total or free testosterone is associated with BMD. Correlations between estradiol and BMD are much stronger, but estradiol plays a little role in race and ethnic differences in BMD. Finally, associations between hormones and BMD are consistent across the race and ethnic groups studied, implying that the significant race and ethnic differences in skeletal integrity are not a result of differences in the gonadal steroid hormonal milieu.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gretchen R. Esche, M.S., for her programming assistance.

Footnotes

The Boston Area Community Health/Bone Survey was supported by Grant AG 20727 from the National Institute on Aging. The parent study (Boston Area Community Health) was supported by Grant DK 56842 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. B.Z.L. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant K23-RR16310.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 25, 2008

Abbreviations: BACH, Boston Area Community Health; BMD, bone mineral density; CI, confidence interval; DXA, dual x-ray absorptiometry; ED, erectile dysfunction; PASE, Physical Activity for the Elderly.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2004 Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD [Google Scholar]

- NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy 2001 Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285:785–795 [Google Scholar]

- Heaney RP 1995 Bone mass, the mechanostat, and ethnic differences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:2289–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwoll ES, Klein RF 1995 Osteoporosis in men. Endocr Rev 16:87–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC, Lindsay RL, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP 1997 Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 12:1761–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo AB, Travison TG, Harris SS, Holick MF, Turner AK, McKinlay JB 2007 Race/ethnic differences in bone mineral density in men. Osteoporos Int 18:943–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barondess DA, Nelson DA, Schlaen SE 1997 Whole body bone, fat, and lean mass in black and white men. J Bone Miner Res 12:967–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley JA, Fullman RL, Stone KL, Zmuda JM, Bauer DC, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud K, Lau EM, Orwoll ES 2005 Factors associated with the lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density in older men. Osteoporos Int 16:1525–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Tracy JK, Meyer WA, Flores RH, Wilson PD, Hochberg MC 2003 Racial differences in bone mineral density in older men. J Bone Miner Res 18:2238–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston Jr CC, Lindsay R 1998 Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton 3rd LJ, Marquez MA, Achenbach SJ, Tefferi A, O'Connor MK, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL 2002 Variations in bone density among persons of African heritage. Osteoporos Int 13:551–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Jacobsen G, Barondess DA, Parfitt AM 1995 Ethnic differences in regional bone density, hip axis length, and lifestyle variables among healthy black and white men. J Bone Miner Res 10:782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehman-Breen CO, Sherrard D, Walker A, Sadler R, Alem A, Lindberg J 1999 Racial differences in bone mineral density and bone loss among end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis 33:941–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, Nevitt MC, Lang TF, Bauer DC, Harris TB 2001 Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res 16:1343–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright NM, Renault J, Willi S, Veldhuis JD, Pandey JP, Gordon L, Key LL, Bell NH 1995 Greater secretion of growth hormone in black than in white men: possible factor in greater bone mineral density–a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:2291–2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S, Zhang Y, Sawin CT, Evans SR, Hannan MT, Kiel DP, Wilson PW, Felson DT 2000 Association of hypogonadism and estradiol levels with bone mineral density in elderly men from the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med 133:951–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center JR, Nguyen TV, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA 1999 Hormonal and biochemical parameters in the determination of osteoporosis in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3626–3635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greendale GA, Edelstein S, Barrett-Connor E 1997 Endogenous sex steroids and bone mineral density in older women and men: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Bone Miner Res 12:1833–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S, Melton 3rd LJ, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Klee GG, Riggs BL 1998 Relationship of serum sex steroid levels and bone turnover markers with bone mineral density in men and women: a key role for bioavailable estrogen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:2266–2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S, Riggs BL, Robb RA, Camp JJ, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, Rouleau PA, Melton 3rd LJ 2005 Relationship of volumetric bone density and structural parameters at different skeletal sites to sex steroid levels in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5096–5103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellstrom D, Johnell O, Ljunggren O, Eriksson AL, Lorentzon M, Mallmin H, Holmberg A, Redlund-Johnell I, Orwoll E, Ohlsson C 2006 Free testosterone is an independent predictor of BMD and prevalent fractures in elderly men: MrOS Sweden. J Bone Miner Res 21:529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc P, Munoz F, Claustrat B, Garnero P, Marchand F, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD 2001 Bioavailable estradiol may be an important determinant of osteoporosis in men: the MINOS study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:192–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc P, Uusi-Rasi K, Claustrat B, Marchand F, Beck TJ, Delmas PD 2004 Role of sex steroids in the regulation of bone morphology in men. The MINOS study. Osteoporos Int 15:909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink HA, Ewing SK, Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor E, Taylor BC, Cauley JA, Orwoll ES 2006 Association of testosterone and estradiol deficiency with osteoporosis and rapid bone loss in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3908–3915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari L, Merlotti D, Martini G, Gonnelli S, Franci B, Campagna S, Lucani B, Dal Canto N, Valenti R, Gennari C, Nuti R 2003 Longitudinal association between sex hormone levels, bone loss, and bone turnover in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5327–5333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S, Melton 3rd LJ, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM 2001 Relationship of serum sex steroid levels to longitudinal changes in bone density in young versus elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3555–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pottelbergh I, Goemaere S, Kaufman JM 2003 Bioavailable estradiol and an aromatase gene polymorphism are determinants of bone mineral density changes in men over 70 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3075–3081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis L, Nyborg H 1992 Racial/ethnic variations in male testosterone levels: a probable contributor to group differences in health. Steroids 57:72–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapstur SM, Gann PH, Kopp P, Colangelo L, Longcope C, Liu K 2002 Serum androgen concentrations in young men: a longitudinal analysis of associations with age, obesity, and race. The CARDIA male hormone study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(10 Pt 1):1041–1047 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwoll E, Lambert LC, Marshall LM, Phipps K, Blank J, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley J, Ensrud K, Cummings S 2006 Testosterone and estradiol among older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1336–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann S, Nelson WG, Rifai N, Brown TR, Dobs A, Kanarek N, Yager JD, Platz EA 2007 Serum estrogen, but not testosterone, levels differ between black and white men in a nationally representative sample of Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2519–2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters SJ, Brufsky A, Weissfeld J, Trump DL, Dyky MA, Hadeed V 2001 Testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, and body composition in young adult African American and Caucasian men. Metabolism 50:1242–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AH, Whittemore AS, Kolonel LN, John EM, Gallagher RP, West DW, Hankin J, Teh CZ, Dreon DM, Paffenbarger Jr RS 1995 Serum androgens and sex hormone-binding globulins in relation to lifestyle factors in older African-American, white, and Asian men in the United States and Canada. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 4:735–741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine RA, Yu MC, Ross RK, Coetzee GA 1995 The CAG and GGC microsatellites of the androgen receptor gene are in linkage disequilibrium in men with prostate cancer. Cancer Res 55:1937–1940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, Montori VM 2006 Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1995–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay JB, Link CL 2007 Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol 52:389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Södergard R, Backstrom T, Shanbhag V, Carstensen H 1982 Calculation of free and bound fractions of testosterone and estradiol-17 beta to human plasma proteins at body temperature. J Steroid Biochem 16:801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM 1999 A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3666–3672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, O'Donnell AB, Travison TG, Williams RE, Clark RV, McKinlay JB 2007 Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:4241–4247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A 1997 The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 49:822–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS 1977 The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- Ware Jr J, Kosinski M, Keller SD 1996 A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34:220–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzankoff SP, Norris AH 1977 Effect of muscle mass decrease on age-related BMR changes. J Appl Physiol 43:1001–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA 1999 The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol 52:643–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA 1993 The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 46:153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG 1977 Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kish L 1965 Survey sampling. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ 1990 Generalized additive models. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC [Google Scholar]

- Litman HJ, Bhasin S, Link CL, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB 2006 Serum androgen levels in black, Hispanic, and white men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4326–4334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travison TG, Araujo AB, Esche GR, Beck TJ, McKinlay JB 2008 Lean mass and not fat mass is associated with male proximal femur strength. J Bone Miner Res 23:189–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leder BZ, LeBlanc KM, Schoenfeld DA, Eastell R, Finkelstein JS 2003 Differential effects of androgens and estrogens on bone turnover in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:204–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falahati-Nini A, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Eastell R, Khosla S 2000 Relative contributions of testosterone and estrogen in regulating bone resorption and formation in normal elderly men. J Clin Invest 106:1553–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahaman E, Raghavan S, Baker L, Weinrich M, Winters SJ 2005 Racial difference in circulating sex hormone-binding globulin levels in prepubertal boys. Metabolism 54:91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbell SO, Raimane KC, Montesano AT, Zeitzer KL, Asbell MD, Vijayakumar S 2000 Prostate-specific antigen and androgens in African-American and white normal subjects and prostate cancer patients. J Natl Med Assoc 92:445–449 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler JL, Gaston KE, Moore DT, Schell MJ, Cohen BL, Weaver C, Petrusz P 2004 Racial differences in prostate androgen levels in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol 171:2277–2280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz EA, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Kantoff PW, Giovannucci E 2000 Racial variation in prostate cancer incidence and in hormonal system markers among male health professionals. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:2009–2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R, Bernstein L, Judd H, Hanisch R, Pike M, Henderson B 1986 Serum testosterone levels in healthy young black and white men. J Natl Cancer Inst 76:45–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsanz V, Skaggs DL, Kovanlikaya A, Sayre J, Loro ML, Kaufman F, Korenman SG 1998 Differential effect of race on the axial and appendicular skeletons of children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1420–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry YM, Eastell R 2000 Ethnic and gender differences in bone mineral density and bone turnover in young adults: effect of bone size. Osteoporos Int 11:512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Simpson PM, Johnson CC, Barondess DA, Kleerekoper M 1997 The accumulation of whole body skeletal mass in third- and fourth-grade children: effects of age, gender, ethnicity, and body composition. Bone 20:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]