Abstract

Background and purpose:

Recombinant cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) oxygenates 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) in vitro. We examined whether prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester (PGE2-G), a COX-2 metabolite of 2-AG, occurs endogenously and affects nociception and immune responses.

Experimental approach:

Using mass spectrometric techniques, we examined whether PGE2-G occurs in vivo and if its levels are altered by inhibition of COX-2, monoacylglycerol (MAG) lipase or inflammation induced by carrageenan. We also examined the effects of PGE2-G on nociception in rats and NFκB activity in RAW264.7 cells.

Key results:

PGE2-G occurs endogenously in rat. Its levels were decreased by inhibition of COX-2 and MAG lipase but were unaffected by carrageenan. Intraplantar administration of PGE2-G induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. In RAW264.7 cells, PGE2-G and PGE2 produced similar, dose-related changes in NFκB activity. PGE2-G was quickly metabolized into PGE2. While the effects of PGE2 on thermal hyperalgesia and NFκB activity were completely blocked by a cocktail of antagonists for prostanoid receptors, the same cocktail of antagonists only partially antagonized the actions of PGE2-G.

Conclusions and implications:

Thermal hyperalgesia and immunomodulation induced by PGE2-G were only partially mediated by PGE2, which is formed by metabolism of PGE2-G. PGE2-G may function through a unique receptor previously postulated to mediate its effects. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that 2-AG is oxygenated in vivo by COX-2 producing PGE2-G, which plays a role in pain and immunomodulation. COX-2 could act as an enzymatic switch by converting 2-AG from an antinociceptive mediator to a pro-nociceptive prostanoid.

Keywords: PGE2-G, 2-AG, COX-2, pain, immunomodulation, inflammation

Introduction

The neuromodulatory actions of endocannabinoids appear to depend on their life span at the synapse which is probably relatively short due to their rapid degradation (see Kozak and Marnett, 2002; van der Stelt and Di Marzo, 2004) and which may lead to new bioactive products with different biological activities. Anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) can be hydrolysed in vivo by fatty acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAG lipase), respectively, into arachidonic acid and ethanolamine or glycerol (Cravatt et al., 1996; Thomas et al., 1997; Dinh et al., 2002, 2004). In addition to these hydrolytic reactions, anandamide can be oxygenated by cyclooxygenases (COXs) (Yu et al., 1997), lipoxygenases (Ueda et al., 1995a, 1995b) and cytochrome P450 (Bornheim et al., 1993, 1995; Snider et al., 2007). 2-AG can also be oxygenated by COXs (Kozak et al., 2000, 2002) and lipoxygenases (Schwarz et al., 1998; Kozak et al., 2002). These same two enzyme systems metabolize arachidonic acid (AA) into a large array of bioactive products such as prostaglandins, prostacyclins, thromboxanes, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids and leukotrienes.

The inducible isoform of COX, COX-2, produces a variety of metabolites of 2-AG in vitro, including a variety of prostaglandin glycerol esters (PG-Gs) such as prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester (PGE2-G), PGD2-G, PGI2-G and PGF2α-G (Kozak et al., 2000, 2001). Indeed, both human and murine COX-2 metabolize 2-AG as efficiently as arachidonic acid (Kozak et al., 2000). The production of PG-Gs was also observed in intact cells such as the murine macrophage-like cells RAW264.7 and peritoneal macrophages stimulated with physiological or pathophysiological reagents (Kozak et al., 2000; Rouzer and Marnett, 2005a). One of the COX-2 metabolites of 2-AG, PGE2-G, triggered intracellular Ca2+ mobilization via inositol triphosphate and protein kinase C pathways in RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells (Nirodi et al., 2004). No such effect occurred following treatment with PGE2. Furthermore, PGE2-G caused an inositol triphosphate- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated increase in the frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons, whereas 2-AG and PGE2 caused a decrease in miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (Sang et al., 2006). These findings indicate that PGE2-G is likely to act via a receptor, separate from the prostanoid receptors that mediate the effects of PGE2, which is rapidly generated from PGE2-G exposed to rat plasma (Kozak et al., 2001).

The findings discussed above are interesting and potentially important, but the question of whether PGE2-G is formed in vivo has not been addressed. Here, we used liquid chromatography (LC)/mass spectrometry (MS)/MS and quadrupole time-of-flight (QqTOF) mass spectrometric approaches to show that PGE2-G is formed in rat tissues and investigated the potential role of COX-2 and MAG lipase in the production of PGE2-G as well as the effects of carrageenan, which induces COX-2 in skin raising the levels of PGE2 (Guay et al., 2004; Toriyabe et al., 2004). We extended the pharmacological characterization of PGE2-G, specifically examining its ability to elicit thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, its modulation of nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) in RAW264.7 cells and the extent to which its biological activity is dependent upon its metabolism to PGE2.

Prostaglandin E2 is a prostaglandin well known for its pro-nociceptive and proinflammatory actions (see Funk, 2001; Hofacker et al., 2005). COX inhibitors, which are among the class of drugs referred to as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, are the first line of treatments for inflammation, mild to moderate pain and fever. On the other hand, endocannabinoids such as anandamide or 2-AG usually exert antinociceptive effects when administered systemically (Smith et al., 1994; Di Marzo et al., 2000). Recent studies suggest that endocannabinoids may play a major role in mediating the spinal antinociception induced by the COX inhibitor flurbiprofen, indicating an interaction between endocannabinoids and COXs (Ates et al., 2003). Thus, it is of interest to test the possibility that COX-2 acts as an enzymatic switch, converting an antinociceptive/anti-inflammatory mediator, such as the endocannabinoid, 2-AG, into a pro-nociceptive/proinflammatory mediator such as PGE2-G.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures involved male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighing 300–400 g to be used as subjects in the experiments. All animals were housed in groups under controlled lighting conditions (lights on from 0700 to 1900 h) and at room temperature. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Cell culture

RAW264.7, a mouse macrophage-like cell line, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Boston, MA, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, penicillin, streptomycin and foetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA). RAW264.7 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS, 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified air.

Partial purification of PGE2-G from mammalian tissues

Animals were killed by decapitation and tissues were dissected with forceps on an ice-cold metal dissection plate. Tissues from brains, spinal cords and hind paws were analysed. Tissues were placed in 15 ml polypropylene tubes, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C before lipid extraction. Frozen samples in 20 volume ice-cold methanol were homogenized with a Brinkmann polytron (Mississauga, Canada) for 2–3 min and centrifuged at 27 000 g at 4 °C for 20 min. Supernatants were removed and H2O was added to a final concentration of 25% methanol. Bond–Elut cartridges (500 mg C18) were conditioned with 5 ml methanol and 2.5 ml high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade water. The extract was then loaded and passed through by gentle, low-pressure aspiration. After washing with 2 ml water and 1.5 ml of 65% methanol, PGE2-G was eluted from cartridges with 1.5 ml 80% methanol. The eluent was evaporated under vacuum, reconstituted in 33% (v/v) acetonitrile in water and subjected to analysis by LC/MS. PGE2-G was chromatographed by gradient elution (0.2 ml min−1): mobile phase A, 5% methanol, 1 mM ammonium acetate; mobile phase B, 100% methanol, 1 mM ammonium acetate; 0% mobile phase B to 100% mobile phase B in 30 min, held at 100% mobile phase B for 8 min, followed by 2 min re-equilibration with 0% mobile phase B.

Quantitative analysis of extracts was performed with an Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex (Foster City, CA, USA) API 3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC/MS/MS) equipped with heat-assisted electrospray ionization and operated in the positive-ion mode. Levels of PGE2-G were analysed in multiple-reaction monitoring mode (MRM) on the LC/MS/MS system. MS parameters were optimized using direct flow injection analysis of synthetic PGE2-G standards. For quantitation, the area under the peak at the appropriate retention time was obtained. The amount of PGE2-G in samples from extracts was then extrapolated from a calibration curve on the basis of synthetic standards. Although the ammonium adduct of the molecular ion was detected, source fragmentation produced additional ions with mass-to-charge ratios consistent with the loss of one or two of the four hydroxyl groups contained in PGE2-G. Hence, the Q1 analyser filtered for the ammonium adduct of the precursor ion mass [M+NH4]+ (m/z=444.5) as well as for the [M+NH4]+ adduct precursor mass minus one and two of the hydroxyl groups. The Q3 analyser was assigned to detect the most abundant fragment ions of the PGE2 moiety. Thus, the m/z transitions for detection of PGE2-G were as follows: 444.5 → 391.3; 444.5 → 409.3; 409.3 → 391.2; 409.3 → 91.2; 391.3 → 91.2; 391.3 → 79.1. For computing percent recovery, standards (10 μl of 10 μM deuterated prostaglandin D2) were added to the samples and the 65% methanol elution was used for quantification of deuterated prostaglandin D2, which was used to correct for sample loss during extraction and solid-phase cleanup. LC/MS/MS was operated in negative-ion mode for deuterated prostaglandin D2 detection, with m/z 359.3 → 315.4 as the precursor → product ion pair.

Nano-HPLC quadrupole TOF analysis

Exact mass measurements and structural characterization of the PGE2-G from rat hindpaw extracts were accomplished using a QqTOF mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization nano-source (QStar Pulsar; Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex). The hindpaw extract was partially purified on solid-phase extraction columns as described above, and subjected to further purification on a semi-preparative HPLC column at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1 (Zorbax eclipse XDB-C18 5 μm, 9.4 × 250 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Chromatographic gradients began with 0% mobile phase B (100% methanol) and 100% mobile phase A (20% methanol), held for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient from 0% mobile phase B to 100% mobile phase B over 38 min and then held at 100% mobile phase B for 10 min. Fractions (1 ml) were collected, evaporated under vacuum and reconstituted in 30% methanol for MS analysis. Fraction 21, which contained a compound that exhibited a PGE2-G-like MRM profile, was further analysed by nano-HPLC/electrospray on a QqTOF mass spectrometer. A nano-HPLC column (∼9 cm × 75 μm; New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA, self-pack with integrated tips) was loaded with C18 beads (Magic C18, 3 μm 100 Å; Microm Bioresources Inc., Auburn, CA, USA) using a helium ‘bomb.' HPLC was carried out with a gradient nano-HPLC system (Micro-Tech Scientific Inc., Vista, CA, USA) at a flow rate of 250 nl min−1. Chromatographic gradients began with 15% mobile phase B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, 1 mM ammonium acetate) and 85% mobile phase A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, 1 mM ammonium acetate), held for 30 min during sample loading, followed by a linear gradient from 15% mobile phase B to 100% mobile phase B over 15 min, and then held at 100% mobile phase B for 30 min. The electrospray ionization voltage of ∼+2000 V generated positively charged [M+NH4]+ molecular and fragment ions. Mass accuracy and resolution were optimized with direct flow injections of synthetic PGE2-G. A blank run was performed prior to tests of tissue extracts to ensure that there was no contamination or carry-over from the synthetic standards used for optimization.

Recombinant COX-2 cell-free assay

AA (6 μM) or 2-AG (6 μM) was incubated separately with 7.2 μl of 0.82 mg ml−1 COX-2 (equivalent to 5.9 μg protein=69.4 U) at 37 °C for 3 min in 100 μl of 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer with 500 μM phenol and 1 μM haematin. The reaction was terminated with 400 μl of ice-cold MeOH (final volume 500 μl, 80% MeOH). For the experiments with COX inhibitors, a non-selective COX inhibitor (ibuprofen, 1 mM) or a selective COX-2 inhibitor (nimesulide, 500 μM) was added before the enzyme and substrate. The solution was submitted for LC/MS/MS analysis according to the quantification methods described above for PGE2 and PGE2-G.

Effect of COX inhibition on PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG levels in the rat hind paw

To examine whether endogenous levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG could be modulated by COX inhibitors, vehicle (Tris buffer+1% Tween 80 for ibuprofen; dimethylsulphoxide for nimesulide), ibuprofen (100 mg kg−1) or nimesulide (50 mg kg−1) was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into rats. The hind paws were removed 2 h after the injection and subjected to partial purification procedures described above for PGE2-G. The levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG in the rat hind paw were quantified by LC/MS/MS.

Effect of MAG lipase inhibition on the levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG in the rat hind paw

The MAG lipase inhibitor [1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl-carbamic acid cyclohexyl ester (URB602) is not suitable for systemic administration due to its relatively low potency (Hohmann et al., 2005; Makara et al., 2005). Thus, vehicle or URB602 (1 μmol in 50 μl dimethylsulphoxide) was injected into the rat hind paw (intraplantar (i.pl.) injection). The hind paws were removed 2 h after the injection and subjected to partial purification procedures described above for PGE2-G. The levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG in the rat hind paw were quantified by LC/MS/MS.

Effect of carrageenan-induced paw inflammation on the levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG in the rat hind paw

The effect of carrageenan-induced peripheral inflammation on the endogenous levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG in the rat hind paw was investigated. The hind paws were removed at 0, 1, 2, 4 or 6 h after i.pl. injection of 2% carrageenan (1 mg in 50 μl saline, i.pl.) and subjected to partial purification procedures described above for PGE2-G. The levels of PGE2-G, PGE2 and 2-AG in the rat hind paw were quantified by LC/MS/MS.

Thermal nociception testing

The latency to withdrawal of the hind paw from a radiant heat source was used as a measure of thermal hyperalgesia (Hargreaves et al., 1988). On the day of the experiment, each rat was placed in a plastic chamber and allowed to acclimatize over a 30-min period. Following determination of baseline withdrawal latencies from the radiant heat source, vehicle or a cocktail of prostanoid PGE2 receptor EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists (L-335677, AH6809, L-826266 and L-161982, respectively; 20 nmol each combined in 50 μl 1:1:18 ethanol:emulphor:saline vehicle) was injected into the plantar surface of the hind paw (i.pl.) of each rat. After 20 min, PGE2-G or PGE2 (0.1, 1 or 10 μg in 50 μl vehicle, i.pl.) was injected in the same manner. The latency to paw withdrawal from the radiant heat source was observed at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 160, 200 and 240 min after injection.

Mechanical nociception testing

A set of von Frey filaments with various bending forces (0.41, 0.70, 1.20, 1.48, 2.00, 3.63, 5.50, 8.51, 11.75, 15.14, 28.8, 75.9, 125.9 g; Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA) was used to test the effect of PGE2-G on mechanical allodynia. Rats were placed in metal cages with wire-mesh bottoms. Beginning with the 1.2 g probe, von Frey filaments of increasing strength were applied sequentially to the plantar surface of a hind paw for 6–8 s in ascending order until the rat made a withdrawal response defined as lifting and/or licking the stimulated hind paw. The force exerted by the effective von Frey filament was recorded. Following determination of withdrawal thresholds, PGE2-G or vehicle (0.1 or 10 μg in 50 μl 1:1:18 ethanol/emulphor/saline vehicle, i.pl.) was injected. The withdrawal thresholds were then recorded at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 160 and 200 min after injection.

NFκB luciferase reporter assay

RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with the pNF-κB-Luc plasmid (5 × NFκB; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) using a mixture of plasmid, Lipofectamine and Plus Reagent in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The control pCMVβ vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) or Renilla plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was co-transfected to monitor transfection efficiency. After 24 h, the cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (100 ng ml−1) for 2 h, and then different concentrations (1, 10, 100 fM; 1, 10, 100 pM; 1, 10, 100, 500 nM; 1, 2, 10, 20 μM) of PGE2-G or dimethylsulphoxide vehicle were added for 30 min. The substrate (Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System; Promega) was then added and the emitted light was quantified by a scintillation counter (Model LS6500; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Data analysis

Data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean. All results, unless otherwise indicated, were analysed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett/Tukey's Honestly Significantly Different (HSD) post hoc test, as appropriate (SPSS Statistical Software, Chicago, IL, USA). The dose- and time-dependent effects of PGE2-G on thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia were analysed by repeated-measure analysis of variance; P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Materials

PGE2-G, PGE2, 2-AG and deuterated prostaglandin D2 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Ibuprofen, nimesulide, carrageenan, AH6809, HPLC-grade acetic acid and ammonium acetate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). URB602 was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). L-335677, L-826266 and L-161982 were kindly provided by Merck Frosst (Kirkland, Canada). HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile and isopropyl alcohol were purchased from VWR International (Plainview, NY, USA) and HPLC-grade water was obtained using a MilliQ Gradient apparatus from Millipore (Milford, MA, USA). Bond–Elut solid-phase extraction cartridges (500 mg C18) were purchased from Varian (Harbor City, CA, USA). A 50 × 2.1-mm Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 reversed-phase HPLC column and a 250 × 9-mm Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 reversed-phase, semi-preparative HPLC column were purchased from Agilent Technologies Inc. A Symmetry C18 reversed-phase HPLC column (2.1 × 100 mm) was purchased from Waters Corporation (Milford, MA, USA).

Results

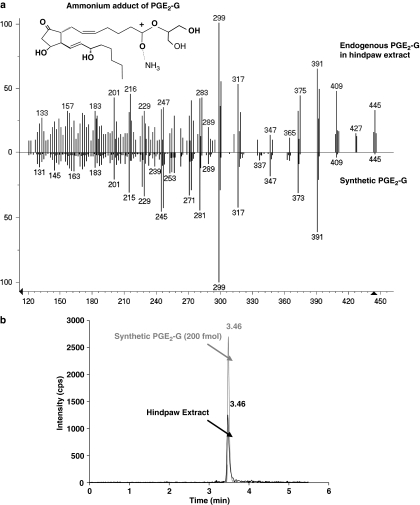

Mass spectrometric identification of PGE2-G

Preliminary identification of endogenous PGE2-G in the rat hindpaw extract was accomplished using an API 3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC/MS/MS), and then additional evidence for its occurrence in vivo was obtained using a QqTOF mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization nano-source (nano-HPLC/QqTOF) (Figure 1). Nano-HPLC/QqTOF MS yielded a mass estimate of 444.2990, which is within 7.7 p.p.m. of the expected mass of the ammonium adduct of PGE2-G with an elemental composition of C23H42O7N for the [M+NH4]+ ion (Table 1). The loss of two water molecules from these ions produced ions at m/z 391. Further loss of the glycerol moiety produced ions at m/z 299. The product ion scans from the material in rat hindpaw extract and synthetic PGE2-G via nano-HPLC/QqTOF produced virtually identical mass spectra (Figure 1a). MRM on a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer revealed co-eluting peaks with molecular/fragment ions 444.5/391.2 for PGE2-G and the material in the rat hindpaw extract, both of which contained the prominent parent ion at m/z 444.5 (M+NH4+ of PGE2-G) and numerous product ions (Figure 1b). The exact mass measurements of the [M+NH4]+ and product ions greatly enhanced the confidence level of structural assignments, leading to reconstruction of the molecule PGE2-G as a naturally occurring material in rat hindpaw extract. Analysis of the rat hindpaw extract using MRM on a triple quadrupole MS revealed that the column retention time, molecular ion mass and the relative ion intensities of six product ions (unit mass accuracy) following collisional activation were virtually identical to those of the ammonium adduct of synthetic PGE2-G. Thus, the constituent isolated from the rat hind paw had the same HPLC retention time, elemental composition and structural components as that of synthetic PGE2-G, thus indicating that PGE2-G is a naturally occurring molecule in the rat hind paw.

Figure 1.

Identification of PGE2-G in the rat hind paw. (a) Identical mass spectra of material in rat hindpaw extract and PGE2-G. The mass spectrum of the material in rat hindpaw extract (top plot) and synthetic PGE2-G (bottom plot) via QqTOF LC/MS/MS were virtually identical. The prominent parent ion at m/z 444.5 [M+ NH3]+ of PGE2-G was observed for the material in the paw extract and synthetic PGE2-G. The inset shows the structure of ammonium adduct of PGE2-G. (b) Multiple-reaction monitoring on a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer revealed co-eluting peaks with molecular/fragment ions at m/z 444.5/391.2 from PGE2-G and the material in rat hindpaw extract. LC, liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester; QqTOF, quadrupole time-of-flight.

Table 1.

Mass measurement of MH+ and product ions from rat paw extract and structural assignments conducted with QqTOF LC/MS/MS

| Putative prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester (PGE2-G) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Common fragments m/z (p.p.m.)a | Proposed formulae | Proposed fragmentation |

| 444.2990 (7.7) | C23H42O7N | MH++NH3 |

| 427.2779 (20.7) | C23H39O7 | MH+ |

| 391.2492 (3.3) | C23H35O5 | MH+−2H2O |

| 373.2353 (−5.5) | C23H33O4 | MH+−3H2O |

| 317.2080 (−9.8) | C20H29O3 | MH+−C3H8O3−H2O |

| 299.2009 (1.1) | C20H27O2 | MH+−C3H8O3−2H2O |

| 281.1910 (3.6) | C20H25O | MH+−C3H8O3−3H2O |

Abbreviations: LC, liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; QqTOF, quadrupole time-of-flight.

Mass measurements and errors (p.p.m. difference from theoretical exact mass) of at least 10 consecutive scan averages.

It is noteworthy that in Figure 1a there are a few additional peaks in the naturally occurring PGE2-G spectrum when compared with the peaks in a PGE2-G standard. Such peaks are common because the partially purified extract is mass filtered in the quadrupole section of the QqTOF to unit mass accuracy. As a result, small peaks resulting from minor contaminants in the sample having the same nominal mass and HPLC retention time as the desired analyte are common.

Whereas PGE2-G was found in the rat paw, its levels in brain and spinal cord were below our detection limit (∼15 fmol on column, 2:1 signal:noise ratio). PGE2-G was detected in brain by MRM when extracts of 6 g of brain tissues were combined (data not shown). These findings indicate that PGE2-G is produced endogenously and occurs mainly in the periphery.

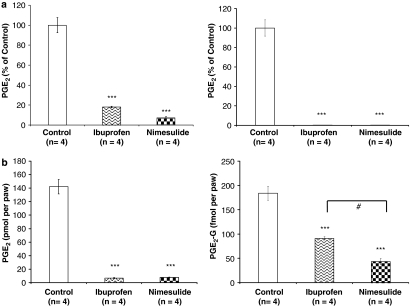

Biosynthesis of PGE2-G by COX-2

Incubation of AA with purified recombinant human COX-2 led to the production of PGE2, which was blocked by ibuprofen (1 mM) and nimesulide (500 μM) (F2,9=132.3, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; ibuprofen: P<0.0001; nimesulide: P<0.0001; Figure 2a, left). Confirming a previous report (Kozak et al., 2000, 2001), incubation of 2-AG with purified recombinant human COX-2 led to the production of PGE2-G, which was absent when COX-2 was blocked by ibuprofen or nimesulide (F2,9=143.0, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; ibuprofen: P<0.0001; nimesulide: P<0.0001; Figure 2a, right). In the absence of inhibitors, approximately 42% of AA was converted into PGE2, whereas 58% of 2-AG was converted into PGE2-G. This result indicated that 2-AG is a better substrate for COX-2 in vitro when compared with AA.

Figure 2.

COX inhibitors modulate the endogenous levels of PGE2 and PGE2-G in the rat hind paw. (a) Effects of COX inhibitors on the in vitro production of PGE2 (left) and PGE2-G (right). AA or 2-AG (6 μM) were incubated with COX-2 (5.9 μg protein=69.4 U) at 37 °C for 3 min. As shown, 42% of AA and 58% of 2-AG were oxygenated into PGE2 and PGE2-G, respectively (shown as 100% yield). The production of PGE2 and PGE2-G was significantly decreased in the presence of the nonselective COX inhibitor ibuprofen (1 mM) or the selective COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide (500 μM) (***P<0.0001). (b) Effects of COX inhibitors on the in vivo production of PGE2 (left) and PGE2-G (right). Ibuprofen (100 mg kg−1, i.p.) or nimesulide (50 mg kg−1, i.p.) was injected, and 2 h later the rat hind paws were removed, homogenized, extracted, and partially purified, and subjected to LC/MS/MS to measure the endogenous level of PGE2 and PGE2-G. Both ibuprofen and nimesulide significantly decreased the levels of PGE2 and PGE2-G in the rat hind paw (***P<0.0001). AA, arachidonic acid; 2-AG, 2-arachidonoylglycerol; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; i.p., intraperitoneally; LC, liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester. #P<0.05 (ibuprofen vs nimesulide).

Systemically administered ibuprofen (100 mg kg−1) and nimesulide (50 mg kg−1) reduced the levels of PGE2 in the rat hind paws relative to animals injected with vehicle (F2,15=153.7, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; ibuprofen: P<0.0001; nimesulide: P<0.0001; Figure 2b, left). Likewise, ibuprofen and nimesulide significantly decreased the endogenous level of PGE2-G in the rat hind paw (F2,15=58.5, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; ibuprofen: P<0.0001; nimesulide: P<0.0001; Figure 2b, right). By contrast, neither ibuprofen nor nimesulide altered the level of 2-AG in the rat hind paw (F2,15=2.3, P>0.05, data not shown).

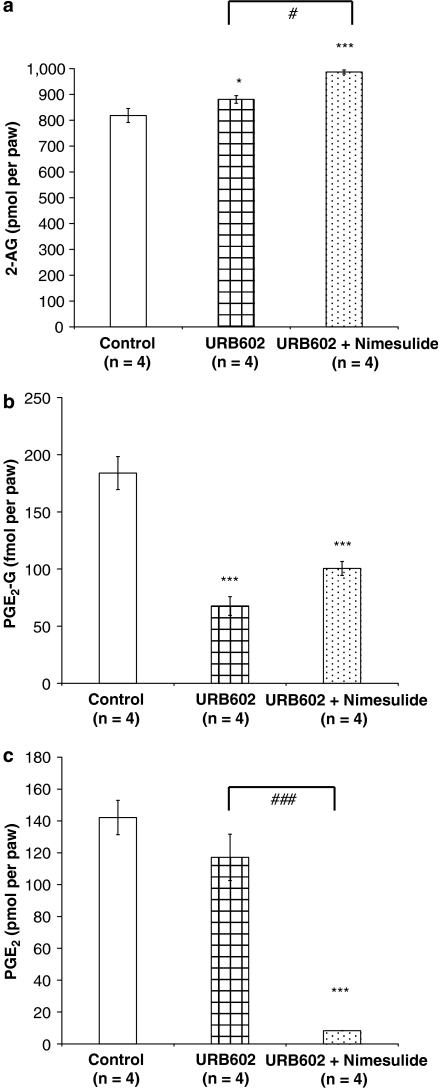

Examination of the role of MAG lipase in the formation of PGE2-G

The effects of the MAG lipase inhibitor, URB602, on the in vivo levels of 2-AG, PGE2-G and PGE2 were examined, either when given alone (1 μmol, i.pl.) or together with nimesulide (50 mg kg−1, i.p.). An increase in the endogenous level of 2-AG was observed following treatment with the MAG lipase inhibitor URB602 (1 μmol, i.pl.) or with the combination of URB602 and the COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide (F2,9=21.7, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; URB602: P<0.05; URB602+nimesulide: P<0.0001). The 2-AG level in rats treated with URB602 plus nimesulide was significantly higher than that in rats treated with URB602 alone (Tukey's HSD, P<0.05; Figure 3a), suggesting greater availability of the substrate. By contrast, the level of PGE2-G in rats treated with URB602 or the combination of URB602 and nimesulide was significantly lower than that observed in vehicle-treated rats (F2,9=34.5, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; URB602: P<0.0001; URB602+nimesulide: P<0.0001; Figure 3b). This result suggested that PGE2-G is a poor substrate for MAG lipase, and it is possible that URB602, a relatively new compound, has functions other than inhibiting MAG lipase. URB602 alone did not change the level of PGE2 in the rat hind paw (Dunnett's post hoc test, P>0.05; Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of MAG lipase modulates the endogenous levels of 2-AG and PGE2-G in the rat hind paw. The MAG lipase inhibitor, URB602, was injected into rats (1 μmol 50 μl−1, i.pl.) alone or in combination with the selective COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide (50 mg kg−1, i.p.), and 2 h later rat hind paws were removed, homogenized, extracted, partially purified and subjected to LC/MS/MS to measure endogenous level of PGE2 and PGE2-G. (a) Both URB602 and URB602+nimesulide significantly increased the level of 2-AG in the rat hind paw (*P<0.05, ***P<0.0001, #P<0.05). (b) Both URB602 and URB602+nimesulide significantly decreased the level of PGE2-G in the rat hind paw (***P<0.0001). (c) URB602 alone did not change the level of PGE2 in the rat hind paw (P>0.05). URB602+nimesulide significantly decreased the level of PGE2 in the rat hind paw (***P<0.0001, ###P<0.05). 2-AG, 2-arachidonoylglycerol; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; i.p., intraperitoneally; i.pl., intraplantar; LC, liquid chromatography; MAG, monoacylglycerol; MS, mass spectrometry; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester; URB602, [1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl-carbamic acid cyclohexyl ester.

Effects of inflammation on the endogenous levels of PGE2-G

At 1, 2, 4 and 6 h after the induction of carrageenan-induced peripheral inflammation (2%, i.pl.), an increase in the level of PGE2 was observed in the hind paw (F4,9=9.5, P<0.015), as expected from previous research (Guay et al., 2004; Toriyabe et al., 2004). However, the levels of PGE2-G and 2-AG were not altered by carrageenan-induced inflammation (data not shown).

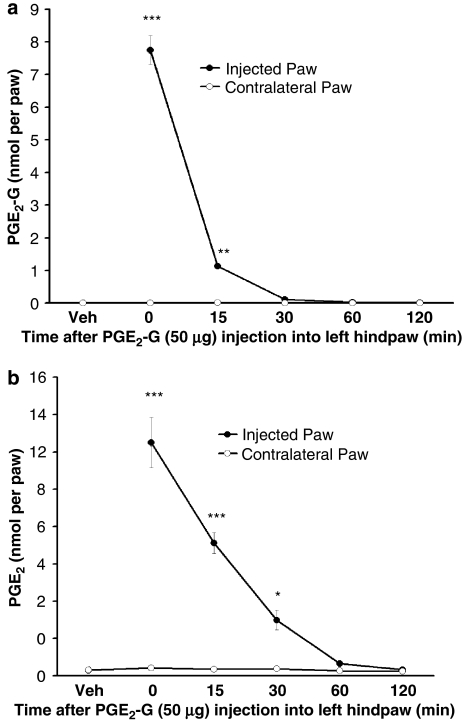

Kozak et al. (2001) showed that PGE2-G is rapidly hydrolysed into PGE2 and glycerol upon exposure to plasma, raising the question of its stability in skin. Extraction and mass spectrometric analysis of paw tissue immediately after injection of PGE2-G (50 μg) revealed that only 6.8% of the injected PGE2-G was recovered, and by 30 min the amount of PGE2-G recovered was not significantly different from the basal level (F5,18=284.1, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; PGE2-G at 0 min: P<0.0001; PGE2-G at 15 min, P<0.001; PGE2-G at 30 min: P>0.05; PGE2-G at 60 min: P>0.05; PGE2-G at 120 min: P>0.05, when compared with the control group; Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

PGE2-G was hydrolysed into PGE2 and other unknown metabolites after it was injected into the rat hind paw. (a) Levels of PGE2-G following its injection into the rat hind paw. Hind paws were removed at 0, 15, 30, 60 or 120 min following PGE2-G injection (50 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl.), extracted, partially purified and subjected to LC/MS/MS to measure the level of PGE2-G. At 0 and 15 min, only 6.8 and 1%, respectively, of the injected amount of PGE2-G were recovered (***P<0.0001, **P<0.001). The amount of PGE2-G fell to the baseline level 30 min after injection. (b) Rat hind paws were removed at 0, 15, 30, 60 or 120 min after PGE2-G injection (50 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl) and the levels of PGE2 were assessed by LC/MS/MS. Immediately after injection (0 min), approximately 10% of the injected amount of PGE2-G was hydrolysed into PGE2 and the level of PGE2 then decreased with time (***P<0.0001, *P<0.05). i.pl., intraplantar; LC, liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester.

It was clear that some of the PGE2-G is hydrolysed into PGE2 and glycerol because the amount of PGE2 measured in the rat hind paw at 0 and 15 min corresponded to 10 and 6% of the molar equivalent of the amount of PGE2-G injected, and the level decreased over time (F5,18=60.6, P<0.0001, Dunnett's post hoc test; PGE2 at 0 min: P<0.0001; PGE2 at 15 min: P<0.0001; PGE2 at 30 min: P<0.05; PGE2 at 60 min: P>0.05; PGE2 at 120 min: P>0.05, when compared with the control group). The level of 2-AG was only slightly increased at 0, 15 and 30 min after the PGE2-G injection (F5,18=2.972, P<0.05, Dunnett's post hoc test; 2-AG at 0 min: P<0.05; 2-AG at 15 min: P<0.05; 2-AG at 30 min: P<0.05; 2-AG at 60 min: P>0.05; 2-AG at 120 min: P>0.05, when compared with the control group; Figure 4b).

Nociceptive behaviour following administration of PGE2 and PGE2-G

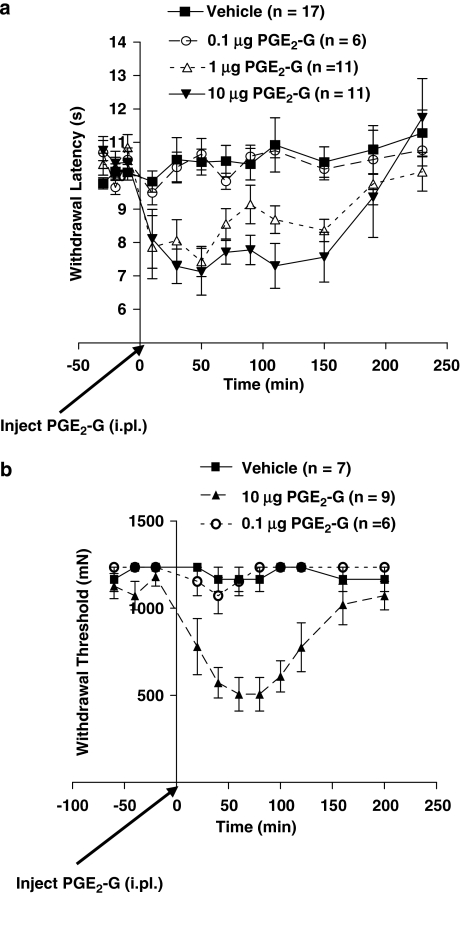

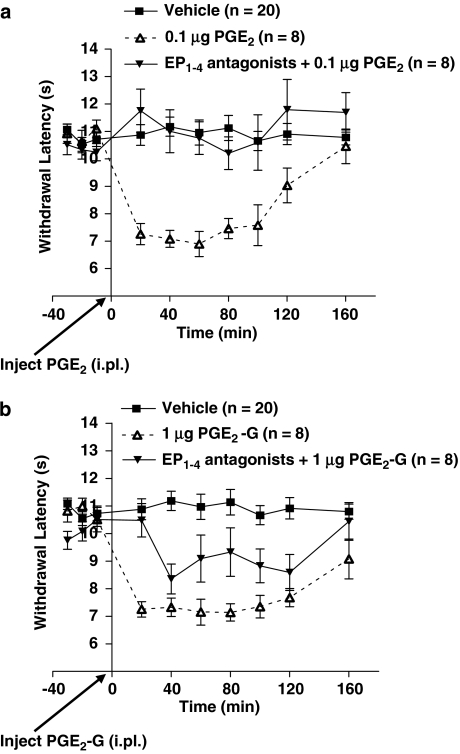

Intradermal administration of PGE2-G into the rat hind paw (i.pl.) dose and time dependently induced thermal hyperalgesia with an EC50 of 0.66±0.41 μg (F3,41=17.7, P<0.0001; Figure 5a). Similarly, peripherally administered PGE2-G induced mechanical allodynia (F2,19=19.3, P<0.0001; Figure 5b). Owing to the rapid hydrolysis of PGE2-G to PGE2, we considered the possibility that much, if not all, of the observed effect was mediated by the latter. Therefore, we compared the effects of prostanoid receptor antagonists on thermal hyperalgesia produced by PGE2 and PGE2-G. Intradermal injections of PGE2 (0.1 μg, i.pl.) caused a decrease in withdrawal latency to noxious radiant heat directed at the hind paw (F2,33=19.3, P<0.0001, Tukey's HSD post hoc test; vehicle vs PGE2: P<0.0001; Figure 6a).

Figure 5.

PGE2-G produced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia. (a) After determination of baseline withdrawal latencies from a radiant heat source, PGE2-G (0.1, 1 or 10 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl.) was administered and withdrawal latencies were measured at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 160, 200 and 240 min after injection. PGE2-G produced a dose- and time-dependent decrease in withdrawal latency (F3,41=17.7, P<0.0001). (b) Following determination of mechanical withdrawal thresholds with von Frey filaments, PGE2-G (0.1 or 10 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl.) was injected. Withdrawal thresholds were recorded at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 160 and 200 min after injection. PGE2-G produced a dose- and time-dependent decrease in withdrawal thresholds (F2,19=19.3, P<0.0001). i.pl., intraplantar; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester.

Figure 6.

PGE2-G-induced thermal hyperalgesia is partially mediated by prostanoid receptors. (a) After determination of baseline withdrawal latencies from a radiant heat source, PGE2 (0.1 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl.) or PGE2 (0.1 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl.) combined with a cocktail of EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists (L-335677, AH6809, L-826266 and L-161982) (20 nmol 50 μl−1, i.pl.) was administered and withdrawal latencies were recorded for the following 160 min. PGE2 (0.1 μg) caused a decrease in withdrawal latency (P<0.0001), which was completely blocked by a cocktail of EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists. (b) Using the same treatment protocol as in (a), PGE2-G (1 μg 50 μl−1, i.pl.) caused a decrease in withdrawal latency, but the cocktail of prostanoid receptor antagonists (20 nmol 50 μl−1, i.pl.) only partially blocked its effects. The degree of reversal was significantly less than that produced by PGE2 (P<0.0001). EP, PGE2 receptor; i.pl., intraplantar; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester.

Prostaglandin E2-induced thermal hyperalgesia was completely blocked by co-administration of a cocktail of EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists (Tukey's HSD post hoc test; vehicle vs PGE2+EP1–4 antagonists: P>0.05; PGE2 vs PGE2+EP1–4 antagonists: P<0.0001; Figure 6a). Likewise, intradermal injections of PGE2-G (1 μg, i.pl.) induced thermal hyperalgesia, the magnitude and time course of which was virtually identical to that induced by 0.1 μg of PGE2 (Figures 5 and 6, F2,33=26.6, P<0.0001, Tukey's HSD post hoc test; vehicle vs PGE2-G: P<0.0001). However, PGE2-G-induced thermal hyperalgesia was only partially reversed by co-administration of the cocktail of EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists, the degree of inhibition by the antagonists being significantly lower in rats treated with PGE2-G compared to animals treated with PGE2 (F1,14=7.8, P<0.015; Figure 6b). Administration of a cocktail of EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists alone in the absence of PGE2 or PGE2-G did not change thermal stimulus-induced withdrawal latencies (data not shown). These findings indicate that the hyperalgesic effects of PGE2-G are mediated in part by its metabolite PGE2. However, if the hyperalgesic effects of PGE2-G were mediated entirely by PGE2 or another metabolite acting as a full agonist at prostanoid receptors, the antagonist cocktail would have produced a full reversal of the effect, because the equi-efficacious doses would imply equal levels of prostanoid receptor occupancy and, therefore, an equal effect of the antagonist cocktail. Hence, although the effect of PGE2-G is mediated in part by prostanoid receptors, probably due to its metabolism to PGE2, it also produces effects that are independent of prostanoid receptors, which may be mediated by a unique PGE2-G receptor (Nirodi et al., 2004).

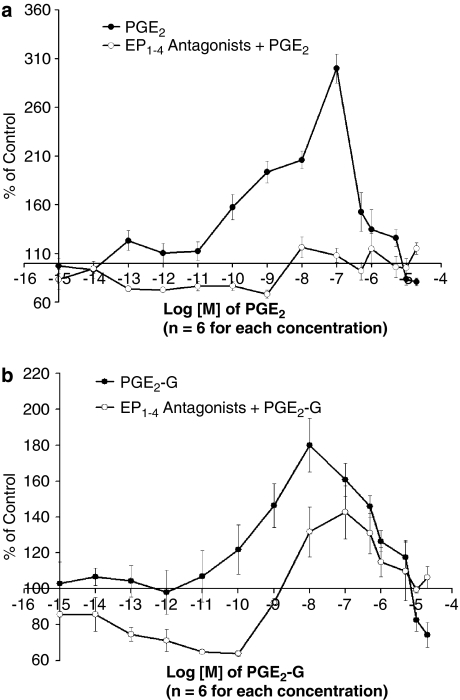

NFκB activation in immune cells by PGE2 and PGE2-G

When compared with vehicle-treated cells, cells treated with low concentrations of PGE2 or PGE2-G showed increases in NFκB activity, whereas cells treated with higher concentrations of PGE2 or PGE2-G showed decreases in NFκB activity (Figure 7). However, in contrast to the effects of PGE2, which were completely blocked by the cocktail of prostanoid receptor antagonists (Figure 7a), the effects of PGE2-G were only partially blocked by the cocktail of prostanoid receptor antagonists (Figure 7b; antagonism of PGE2 versus PGE2-G: F1,162=8.7, P<0.04). The significantly greater antagonism by prostanoid receptor antagonists of PGE2 compared to PGE2-G administered at equi-efficacious doses indicates that the effects of PGE2-G are partially but not wholly mediated by prostanoid receptors.

Figure 7.

The immunomodulatory effects of PGE2-G on NFκB activity in RAW264.7 cells was partially mediated by prostanoid receptors. RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with the NFκB-Luc plasmid and 24 h later the cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (100 ng ml−1) for 2 h, followed by various concentrations of PGE2, PGE2-G or vehicle (dimethylsulphoxide), or a combination with a cocktail of EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 antagonists (L-335677, AH6809, L-826266 and L-161982, 50 μM preincubated for 30 min). (a) PGE2 produced a bell-shaped dose–response curve of NFκB activity, which was completely blocked by a cocktail of prostanoid receptor antagonists. (b) PGE2-G produced a bell-shaped dose–response curve of NFκB activity, which was only partially blocked by a cocktail of prostanoid receptor antagonists. The degree of inhibition by the cocktail of antagonists was significantly greater for cells treated with PGE2 compared with those treated with PGE2-G (P<0.04). EP, PGE2 receptor; NFκB; nuclear factor-κB; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGE2-G, prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester.

Discussion and conclusions

The current study showed that PGE2-G is a naturally occurring molecule in the rat, a conclusion based upon mass spectrometric analysis showing that the exact masses, column retention times and fragmentation patterns of the constituent found in rat hind paw were virtually identical to those of PGE2-G. These findings, together with the observation that PGE2-G levels are markedly reduced following inhibition of COX-2 indicated that 2-AG is oxygenated by COX-2 to produce PGE2-G in vivo. These findings extend those of Kozak et al. (2000) (2001) and Rouzer and Marnett (2005a) by showing that oxygenation of 2-AG by COX-2 observed with the recombinant enzyme, RAW264.7 cells, or resident peritoneal macrophages are, in fact, reflective of an in vivo metabolic pathway.

The amount of PGE2-G found in the rat hind paw (∼180 fmol paw−1) was low relative to the nmol g−1 levels of 2-AG found in many mammalian tissues (Stella et al., 1997; Kondo et al., 1998; Fezza et al., 2002). Indeed, the levels of PGE2-G in rat brain and spinal cord were below our detection limit (∼15 fmol on column) unless tissues from multiple animals were combined. This may indicate that very little 2-AG is metabolized by COX-2 in vivo, or it may be a result of the rapid hydrolysis of PGE2-G into PGE2 as observed previously (Kozak et al., 2001) and in the experiments performed here. Although exposure to rat plasma and skin led to rapid hydrolysis of PGE2-G (t1/2=14 s), this was not the case for human plasma (t1/2>10 min) or canine, bovine or human cerebrospinal fluid (Kozak et al., 2001). Thus, PGE2-G may be more abundant in particular species or in particular cellular compartments in rats. While our mass spectrometric data showed that PGE2-G exists in the rat hind paw, the types of cells that produce this compound remain to be elucidated. It is possible that PGE2-G is produced by immune cells such as macrophage cells (Kozak et al., 2000, 2001; Rouzer and Marnett, 2005a), blood cells, keratinocytes, or nerve endings in the skin. Hence, more work will be needed to address this question, which is important for clarifying its functions in vivo.

Previous research showed that PGE2-G can be made in intact macrophage cells stimulated with physiological or pathophysiological reagents (Kozak et al., 2000; Rouzer and Marnett, 2005a). The levels of endogenous PGE2-G found in the rat hind paw were approximately 1000-fold lower than those of endogenous PGE2 in the same sample (Figures 3b and c, PGE2-G 180 fmol per paw vs PGE2 140 pmol per paw). This ratio is similar to that found by Rouzer and Marnett (2005a) in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide, zymosan, or both (PGE2-G 15 pmol per 107 cells vs PGE2 15 000 pmol per 107 cells). This similarity may be coincidental, but the similar ratios may represent an equilibrium between the production of PGE2-G and PGE2 both in vivo and in intact cells.

Although much remains to be learned about the molecular basis for the actions of PGE2-G, its distinctive effects suggest the existence of a unique PGE2-G receptor. Whereas we observed actions of PGE2-G that were similar to those of PGE2, this was not the case in other studies. For example, PGE2-G induced intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in RAW 264.7 cells (Nirodi et al., 2004) and caused an increase in the frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents and miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents in primary hippocampal neurons (Sang et al., 2006, 2007), both actions being opposite to those of PGE2. The unique and sometimes highly potent effects of PGE2-G suggest that it binds to a novel receptor. As discussed in more detail below, the results of our studies of thermal hyperalgesia and NFκB activation also suggest that PGE2-G binds to a unique receptor to induce pain and immune modulation. Thus, PGE2-G may be a novel signalling molecule with functions distinct from its precursors and metabolites.

COX inhibitors reduced the levels of endogenous PGE2 and PGE2-G, indicating that PGE2-G, like PGE2, is a product of COX-2 oxygenation. However, COX-2 inhibition did not cause accumulation of 2-AG, the putative precursor to PGE2-G, in the rat hind paw. It appears that when COX-2 is inhibited, 2-AG continues to be metabolized by other enzymes, a likely possibility being MAG lipase (Dinh et al., 2002, 2004). Alternatively, the rate of metabolism by COX-2 of 2-AG may be insufficient to produce observable differences in the levels of 2-AG, or the pools of 2-AG that are subject to COX-2 metabolism may represent a small fraction of the total.

We hypothesized that both PGE2-G and 2-AG levels would increase following inhibition of MAG lipase, due to accumulation of the putative precursor 2-AG and possibly reduced metabolism by MAG lipase of PGE2-G itself. While the MAG lipase inhibitor URB602 produced the expected increase of the level of 2-AG in the rat hind paw, the level of PGE2-G fell. This suggests that PGE2-G is a poor substrate for MAG lipase, confirming a similar finding published during the preparation of this manuscript (Vila et al., 2007). Understanding the basis for the decrease in the level of PGE2-G will require further research, but it suggests that URB602, a relatively new compound, has functions other than inhibiting MAG lipase. Although many possible actions could be hypothesized, actions of URB602 on fatty acid amide hydrolase , diacylglycerol lipase and COX-2 (Tarzia et al., 2003; Hohmann et al., 2005) have been ruled out.

Our results confirmed previous reports (Guay et al., 2004; Toriyabe et al., 2004) of increased levels of PGE2 after peripheral carrageenan administration. By contrast, the levels of PGE2-G and 2-AG were unchanged after peripheral administration of carrageenan. These results are surprising because PGE2-G was shown to be produced in intact cells stimulated with other inflammatory reagents (for example, zymosan, Rouzer and Marnett, 2005a). It may be that PGE2-G is produced under other inflammatory conditions and/or is then rapidly hydrolysed into PGE2. In addition to hydrolysis into PGE2, it is possible that the carrageenan-induced inflammation induces an esterase that degrades PGE2-G and/or 2-AG into other metabolites. Alternatively, it is possible that PGE2-G and 2-AG levels change at times later than 6 h which was the latest time point included in the present experiments.

Prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester induced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia. In light of the rapid conversion of PGE2-G into PGE2 in rat plasma (Kozak et al., 2001), it seemed likely that the pro-nociceptive effects of PGE2-G were mediated in part by PGE2, the question being whether PGE2-G exerted any effects apart from those of its metabolite PGE2 acting at prostanoid receptors. PGE2-G would be unlikely to exert direct effects via prostanoid receptors because it binds to EP1 and EP3 receptors with an affinity two orders of magnitude lower than that of PGE2 and it failed to exhibit binding to EP2 and EP4 receptors (Nirodi et al., 2004). Therefore, if the hyperalgesic effects of PGE2-G were secondary to its metabolism to PGE2 acting on prostanoid receptors, then it should be possible to block the effects of PGE2-G with appropriate doses of prostanoid receptor antagonists. We found that the thermal hyperalgesic effects of 1 μg PGE2-G were virtually identical in magnitude and time-course to those produced by 0.1 μg PGE2. If the effects of both PGE2 and PGE2-G were mediated by prostanoid receptors, then the virtually identical efficacies of the two compounds at the doses used would imply equal levels of prostanoid receptor occupancy. In such a case, the antagonist cocktail would be expected to produce the same level of antagonism, which was not observed. Thus, the lack of full reversal of the effects of PGE2-G by the antagonist cocktail indicates that a different mechanism accounts in part for its effects. It thus appears that the residual hyperalgesic effects of PGE2-G was due to the binding of PGE2-G to a unique receptor (Nirodi et al., 2004) or the actions of metabolites of PGE2-G other than PGE2.

Previous data showing intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells suggested that PGE2-G may alter NFκB activity in this line (Nirodi et al., 2004). Both PGE2 and PGE2-G produced activation of NFκB at low doses and suppression at higher doses. There are a number of possible explanations for these bell-shaped dose–response curves, which include binding with different potencies to receptors that mediate opposite effects (Szabadi, 1977), specific desensitization of receptors (Waud, 1968) or induction of receptor cross-linking (Colquhoun, 1968).

As in the behavioral experiments described above, we asked whether the immunomodulatory effect of PGE2-G is mediated by metabolism to PGE2 by attempting to block the effects of PGE2-G with a cocktail of antagonists for prostanoid receptors. Our results showed that, in contrast to the effects of PGE2, which are completely blocked by a cocktail of prostanoid receptor antagonists, the immunomodulatory effects of PGE2-G were only partially blocked by the same cocktail. These results suggested that the immunomodulatory effect of PGE2-G was only partially mediated by its metabolism to PGE2 and subsequent activation of prostanoid receptors.

At the physiological level, it is notable that besides converting 2-AG into a product that may act at a unique receptor, COX-2 appears to serve as a mechanism for terminating the cannabinoid receptor-mediated effects of 2-AG, because PGE2-G does not bind to cannabinoid receptors (Rouzer and Marnett, 2005b). In addition, PGE2-G may act as an eicosanoid pro-drug, a notion based on the rapid conversion of PGE2-G to PGE2, as noted by Kozak et al. (2001) and shown again here. Taken together, these observations suggest that COX-2 can convert the endocannabinoid 2-AG in vivo into a pro-nociceptive compound PGE2-G with physiological effects largely opposite to those of 2-AG. COX-2 may thus serve as an enzymatic switch, converting an antinociceptive/anti-inflammatory lipid mediator (acting through a cannabinoid receptor-mediated mechanism) into a pro-nociceptive/proinflammatory mediator (acting through a non-cannabinoid receptor-mediated mechanisms).

In conclusion, the findings reported here indicate the conversion by COX-2 of 2-AG into PGE2-G occurs in vivo. Despite its rapid conversion into PGE2, PGE2-G produced effects that were independent of prostanoid receptors, which included induction of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia in vivo, and modulation of the activity of the proinflammatory transcription factor NFκB in RAW 264.7 cells.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to Dr J Michael Walker who died on 5 January 2008 while this paper was in press. We are grateful for the editorial assistance of Dr Ken Mackie and Dr Douglas McHugh, and the technical assistance of Y William Yu, Sarah R Pickens and Mauricio X Pazos. This study was supported by grants from National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-018224, DA-020402, DA-011322, F32-DA-016825), the Gill Center for Biomolecular Science, Indiana University, Bloomington and the Lilly Foundation Inc., Indianapolis, IN.

Abbreviations

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase

- EP

PGE2 receptor

- MAG lipase

monoacylglycerol lipase

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PGE2-G

prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester

- URB602

[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl-carbamic acid cyclohexyl ester

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Ates M, Hamza M, Seidel K, Kotalla CE, Ledent C, Gühring H. Intrathecally applied flurbiprofen produces an endocannabinoid-dependent antinociception in the rat formalin test. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:597–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornheim LM, Kim KY, Chen B, Correia MA. The effect of cannabidiol on mouse hepatic microsomal cytochrome P450-dependent anandamide metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:740–746. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornheim LM, Kim KY, Chen B, Correia MA. Microsomal cytochrome P450-mediated liver and brain anandamide metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:677–686. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. The rate of equilibration in a competitive n drug system and the autoinhibitory equations of enzyme kinetics: some properties of simple models for passive sensitization. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1968;170:135–154. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1968.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Melck D, De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T. Cannabimimetic fatty acid derivatives in cancer and inflammation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;61:43–61. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(00)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh TP, Carpenter D, Leslie FM, Freund TF, Katona I, Sensi SL, et al. Brain monoglyceride lipase participating in endocannabinoid inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10819–10824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152334899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh TP, Kathuria S, Piomelli D. RNA interference suggests a primary role for monoacylglycerol lipase in the degradation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1260–1264. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fezza F, Bisogno T, Minassi A, Appendino G, Mechoulam R, Di Marzo V. Noladin ether, a putative novel endocannabinoid: inactivation mechanisms and a sensitive method for its quantification in rat tissues. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:294–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay J, Bateman K, Gordon R, Mancini J, Riendeau D. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in rat elicits a predominant prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) response in the central nervous system associated with the induction of microsomal PGE2 synthase-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24866–24872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker A, Coste O, Nguyen H-V, Marian C, Scholich K, Geisslinger G. Downregulation of cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase results in decreased nociceptive behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9005–9009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2190-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Suplita RL, Bolton NM, Neely MH, Fegley D, Mangieri R, et al. An endocannabinoid mechanism for stress-induced analgesia. Nature. 2005;435:1108–1112. doi: 10.1038/nature03658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Kondo H, Nakane S, Kodaka T, Tokumura A, Waku K, et al. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor agonist: identification as one of the major species of monoacylglycerols in various rat tissues, and evidence for its generation through Ca2+-dependent and -independent mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:152–156. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00581-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Crews BC, Ray JL, Tai HH, Morrow JD, Marnett LJ. Metabolism of prostaglandin glycerol esters and prostaglandin ethanolamides in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36993–36998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Gupta RA, Moody JS, Ji C, Boeglin WE, DuBois RN, et al. 15-Lipoxygenase metabolism of 2-arachidonylglycerol. Generation of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonist. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23278–23286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Marnett LJ. Oxidative metabolism of endocannabinoids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:211–220. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Rowlinson SW, Marnett LJ. Oxygenation of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol, to glyceryl prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33744–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makara JK, Mor M, Fegley D, Szabo SI, Kathuria S, Astarita G, et al. Selective inhibition of 2-AG hydrolysis enhances endocannabinoid signaling in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1139–1141. doi: 10.1038/nn1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirodi CS, Crews BC, Kozak KR, Morrow JD, Marnett LJ. The glyceryl ester of prostaglandin E2 mobilizes calcium and activates signal transduction in RAW264.7 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1840–1845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303950101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Glycerylprostaglandin synthesis by resident peritoneal macrophages in response to a zymosan stimulus. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:26690–26700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Structural and functional differences between cyclooxygenases: fatty acid oxygenases with a critical role in cell signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005b;338:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang N, Zhang J, Chen C. PGE2 glycerol ester, a COX-2 oxidative metabolite of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol, modulates inhibitory synaptic transmission in mouse hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2006;572:735–745. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang N, Zhang J, Chen C. COX-2 oxidative metabolite of endocannabinoid 2-AG enhances excitatory glutamatergic synaptic transmission and induces neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1966–1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz K, Borngraber S, Anton M, Kuhn H. Probing the substrate alignment at the active site of 15-lipoxygenases by targeted substrate modification and site-directed mutagenesis: evidence for an inverse substrate orientation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15327–15335. doi: 10.1021/bi9816204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PB, Compton DR, Welch SP, Razdan RK, Mechoulam R, Martin BR. The pharmacological activity of anandamide, a putative endogenous cannabinoid, in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider NT, Kornilov AM, Kent UM, Hollenberg PF. Anandamide metabolism by human liver and kidney microsomal cytochrome P450 enzymes to form hydroxyeicosatetraenoic and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid ethanolamides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:590–597. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;388:773–778. doi: 10.1038/42015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadi E. A model of two functionally antagonistic receptor populations activated by the same agonist. J Theor Biol. 1977;69:101–112. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(77)90390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarzia G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Piersanti G, Mor M, Rivara S, et al. Design, synthesis, and structure–activity relationships of alkylcarbamic acid aryl esters, a new class of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:2352–2360. doi: 10.1021/jm021119g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EA, Cravatt BF, Danielson PE, Gilula NB, Sutcliffe JG. Fatty acid amide hydrolase, the degradative enzyme for anandamide and oleamide, has selective distribution in neurons within the rat central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:1047–1052. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971215)50:6<1047::AID-JNR16>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toriyabe M, Omote K, Kawamata T, Namiki A. Contribution of interaction between nitric oxide and cyclooxygenases to the production of prostaglandins in carrageenan-induced inflammation. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:983–990. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200410000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N, Yamamoto K, Kurahashi Y, Yamamoto S, Ogawa M, Matsuki N, et al. Oxygenation of arachidonylethanolamide (anandamide) by lipoxygenases. Adv Prostaglandin Thromboxane Leukot Res. 1995a;23:163–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto S, Tokunaga T, Shirakawa E, Shinkai H, et al. Lipoxygenase-catalyzed oxygenation of arachidonylethanolamide, a cannabinoid receptor agonist. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995b;1254:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Stelt M, Di Marzo V. Metabolic fate of endocannabinoids. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2004;2:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vila A, Rosengarth A, Piomelli D, Cravatt B, Marnett LJ. Hydrolysis of prostaglandin glycerol esters by the endocannabinoid-hydrolyzing enzymes, monoacylglycerol lipase and fatty acid amide hydrolase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9578–9585. doi: 10.1021/bi7005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waud DR. Pharmacological receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1968;20:49–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Ives D, Ramesha CS. Synthesis of prostaglandin E2 ethanolamide from anandamide by cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21181–21186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]