Abstract

Background and purpose:

Secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) is implicated in atherosclerosis, although the effects of specific sPLA2 inhibitors have not been studied. We investigated the effects of the indole analogue indoxam on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) modification by sPLA2 enzymes of different types and on the associated inflammatory responses in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC).

Experimental approach:

LDL modification was assessed by measuring the contents of two major molecular species of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) using electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. The proinflammatory activity of the modified LDL was evaluated by determining monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) mRNA expression and transcriptional factor nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) activity in HUVEC.

Key results:

Indoxam dose-dependently inhibited palmitoyl- and stearoyl-LPC production in LDL incubated with snake venom sPLA2 (IC50 1.2 μM for palmitoyl-LPC, 0.8 μM for stearoyl-LPC). MCP-1 mRNA expression and NF-κB activity were enhanced by venom sPLA2-treated LDL, which was completely suppressed by indoxam but not by thioetheramide-PC, a competitive sPLA2 inhibitor. Indoxam also suppressed LPC production in LDL treated with human synovial type IIA sPLA2. Tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) increased type V sPLA2 expression in HUVEC. Indoxam dose-dependently suppressed LPC production in native and glycoxidized LDL treated with TNFα-stimulated HUVEC. Indoxam suppressed MCP-1 mRNA expression and NF-κB activity in TNFα-stimulated HUVEC incubated with native or glycoxidized LDL.

Conclusions and implications:

Indoxam prevented sPLA2-induced LPC production in native and glycoxidized LDL as well as LDL-induced inflammatory activity in HUVEC. Our results suggest that indoxam may be a potentially useful anti-atherogenic agent.

Keywords: secretory phospholipase A2, secretory phospholipase A2 inhibitor, indoxam, lysophosphatidylcholine, atherosclerosis, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, nuclear factor-κB, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, low-density lipoprotein, tumour-necrosis factor α

Introduction

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) catalyses the hydrolysis of the sn-2 ester bond of phospholipids to produce free fatty acids and lysophospholipid. PLA2 belongs to a large superfamily that can be divided into four categories: secretory PLA2 (sPLA2), cytosolic PLA2, Ca2+-independent PLA2 and lipoprotein-associated PLA2 (platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase) (Six and Dennis, 2000; Kudo and Murakami, 2002). sPLA2 is a small disulphide-rich molecule requiring millimolar Ca2+ concentrations for its activity. There are a large number of isoenzymes, currently 10 in humans, with various reported activities such as production of lipid mediators contributing to inflammation or tumorigenesis, fertilization, bacterial defence and phospholipid digestion in the gastrointestinal tract (Kudo and Murakami, 2002; Murakami and Kudo, 2004). These enzymes are associated with a number of diseases, including acute pancreatitis, sepsis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, bronchial asthma and adult respiratory distress syndrome, in which sPLA2 might act to degrade pulmonary surfactant phospholipids.

Secretory PLA2 has also been implicated in atherosclerosis (Hurt-Camejo et al., 2001; Murakami and Kudo, 2003), based on immunohistochemical staining for sPLA2 type IIA, V and X in atherosclerotic tissue (Hurt-Camejo et al., 1997; Hanasaki et al., 2002; Rosengren et al., 2006). The effects of sPLA2 enzymes in the development of atherosclerosis are mainly exerted through their actions on low-density lipoprotein (LDL). First, phosphatidylcholine (PC) is the most abundant phospholipid present in LDL particles, and hydrolysis of PC by sPLA2 yields lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), which has proatherogenic and proinflammatory effects on arterial wall cells, including the upregulation of adhesive molecules, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), growth factors, cell proliferation, cell migration, apoptosis, activation of protein kinase C and inhibition of endothelium-dependent relaxation (Hurt-Camejo et al., 2001; Zalewski and Macphee, 2005). Second, LDL modification by sPLA2 exposes more arginine- and lysine-rich segments that bind strongly to extracellular matrix proteoglycans, resulting in increased retention of LDL particles. These are taken up by macrophages, leading to the formation of foam cells (Camejo et al., 1998). Third, sPLA2 substantially reduces the PC content in the surface monolayer of LDL, resulting in smaller and denser LDL particles that are more susceptible to lipid peroxidation (Neuzil et al., 1998). In fact, transgenic mice expressing human type IIA sPLA2 developed accelerated atherosclerosis with altered lipoprotein levels (Ivandic et al., 1999), and LDL receptor-deficient mice overexpressing human type IIA sPLA2 in macrophages had large atherosclerotic lesions when placed on high-fat diet (Webb et al., 2003).

In light of the potentially causal role of sPLA2 in lipoprotein modification, its inhibition may be beneficial in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis; however, the effects of specific sPLA2 inhibitors on lipoprotein remain unknown. Here, we studied the inhibitory effects of indoxam, a 1-oxamoylindolizine derivative acting as a specific site-directed sPLA2 inhibitor (Hagishita et al., 1996), on LPC production in LDL induced by venom sPLA2, synovial fluid type IIA sPLA2 and type V sPLA2 in activated cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). We also investigated the effect of indoxam on sPLA2-mediated inflammatory activity of native or glycoxidized LDL by assessing the activity of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and MCP-1 mRNA expression in HUVECs. The results showed that indoxam prevented LDL modification and LDL-associated proinflammatory activity elicited by sPLA2.

Methods

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were isolated from umbilical cord veins using 0.25% trypsin (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) as described by Jaffe et al. (1973). HUVECs were grown in M199 medium supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA), 100 μg ml−1 heparin (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), 20 μg ml−1 endothelial cell growth supplement (Upstate Biotechnology, New York, NY, USA) and 0.33 mg ml−1 piperacillin sodium (Sankyo Co., Tokyo, Japan) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells prior to the sixth passage were used. These cells were confirmed to incorporate Dil-acetylated LDL (Sonoki et al., 2002, 2003).

Modification of LDL by sPLA2

Native LDL was isolated from human plasma using density-gradient ultracentrifugation (Vieira et al., 1996). Glycoxidized LDL was prepared by incubating an aliquot of native LDL with 200 mM glucose at 37 °C for 3 days and then with 1 μM CuSO4 at 37 °C for 12 h after three dialyses with 4 l of phosphate-buffered saline. Native or glycoxidized LDL was dialysed against 0.15 M NaCl and 0.26 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, sterilized with a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and then stored at 4 °C under N2 gas until use. The protein concentration of each LDL preparation was determined by the Coomassie brilliant blue method using bovine serum albumin as a standard (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan), and LDL concentrations were adjusted to 1 mg ml−1. For LDL modification by snake venom or human synovial type IIA sPLA2, native LDL was concentrated and dialysed against a 1000-fold volume of 0.05 M HEPES buffer containing 1 M NaCl and 1 M NaOH, pH 7.4, by centrifugation through an Ultrafree-15 centrifugal filter (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA) three times. LDL was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h with snake venom sPLA2 (Crotalus adamanteus; Worthington Biochemical Co., Lakewood, NJ, USA) at 1 U ml−1 or human synovial fluid obtained from a patient with rheumatoid arthritis by arthrocentesis. Type IIA sPLA2 concentration in the synovial fluid was measured by ELISA (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Indoxam ((3-(biphenyl-2-yl)methyl-2-ethyl-1-oxamoyl-1-indolizine-8-yloxy)-acetic acid, molecular weight 456.503, kindly supplied by Shionogi Co., Osaka, Japan) was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide as a stock solution and added to the LDL at various concentrations. Another sPLA2 inhibitor, thioetheramide-PC (Cayman Chemical Co.), was diluted with ethanol and added to the LDL at various concentrations. The LDL was concentrated and dialysed three times against a 1000-fold volume of 0.15 M NaCl and 0.26 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, using an Ultrafree-15 centrifugal filter for elimination of sPLA2, indoxam and thioeheramide-PC and then stored at 4 °C under N2 gas until use for the measurement of LPC content or incubation in HUVECs. For modification of native or glycoxidized LDL by HUVECs, 100 μg ml−1 of native or glycoxidized LDL was incubated in 6 ml of the medium for 2 h with HUVECs partly stimulated before 3 days with 100 ng ml−1 tumour-necrosis factor (TNFα) for 4 h. In some experiments, cells were preincubated with indoxam at various concentrations 1 h before the incubation. LDL was isolated from the medium using density-gradient ultracentrifugation prior to assaying the LPC content.

Electrophoretic mobility of modified LDL

Electrophoresis of modified LDL with or without 100 μM of indoxam or 500 μM of thioetheramide-PC was carried out using a commercial kit (Titan gel lipoproteins; Helena Laboratories, Saitama, Japan). In brief, 1 μl of each modified LDL was loaded on an agarose gel sheet and electrophoresed in barbital buffer at a voltage of 100 V for 30 min. The gel sheet was dried, stained with 0.04% fat red 7B in methanol and the distance from the applied line was measured as the electrophoretic mobility.

Measurement of LPC content in LDL by electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

Measurement of LPC was carried out as described previously (Sonoki et al. 2002). Briefly, lipids were extracted from 100 μl of LDL supplemented with 500 ng of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar-Lipids Inc., Alabaster, AL, USA) as an internal standard. Phospholipids were separated from the extracted lipids by the method of Kaluzny et al. (1985) using aminopropyl solid-phase extraction chromatography (BAKERBOND spe Columns; J.T. Baker Inc., Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). The phospholipids were then introduced into an electrospray mass spectrometer (LCQ, ThermoQuest, Tokyo, Japan) via high-performance liquid chromatography (LC-10; Shimazu, Kyoto, Japan). Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography was performed by injecting 20 μl of isolated phospholipids in methanol into an STR-ODS analytical microcolumn (150 × 2.0 mm, 5 μM; Shimazu) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 and elution with a mobile solvent of methanol/acetonitrile/deionized water (84:14:2 v/v/v). The mass spectrometer was operated in positive mode employing the ‘full-scan' function set from m/z 100 to 1000. Quantitative analysis of phospholipids was performed essentially as described by Han et al. (1996), based on their ion intensity relative to the internal standard. A liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry chromatogram of LDL showed the peaks of palmitoyl-, stearoyl-LPC and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine as an internal standard, with retention times of 2.03 min, 2.50 min and 5.54 min, respectively. The electrospray ionization mass spectrum showed that palmitoyl- and stearoyl-LPC had four masses, that is, m/z 496.5, 497.5, 518.4 and 519.4 for palmitoyl-LPC; m/z 524.6, 525.5, 546.5 and 547.6 for stearoyl-LPC, respectively. The coefficient of variation for the electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry assay was 4.8%, and the standard-curve experiments showed that measurement by this method was linear over a wide range (0.1–5.0 ng μl−1). LPC contents were normalized to LDL protein concentration or HUVEC cell number in each dish.

Measurement of MCP-1 mRNA expression by northern blot analysis

Briefly, total RNA was isolated from HUVECs with TRIzol (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). Total RNA (15 μg) was separated by electrophoresis and transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Hybridization was performed for 1 h at 65 °C in QuikHyb hybridization solution (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) with a human MCP-1 cDNA (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA (Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA, USA) that had been labelled with [γ-32P] ATP (Amersham Biosciences) using the T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA). Autoradiography and quantitative analysis were performed using a Bio-Imaging Analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co., Kanagawa, Japan), and MCP-1 mRNA density was normalized against GAPDH density.

Measurement of NF-κB activity by electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear factor-kappa B activity was measured by electrophoretic mobility shift assay, as described previously (Sonoki et al., 2002). Briefly, 25 μl of 10% nonidet P-40 (Sigma) was added to HUVECs suspended in 0.4 ml buffer. The mixture was centrifuged and the nuclear pellet was suspended in 50 μl of ice-cold buffer. The suspension was sonicated and shaken at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant of nuclear extracts was centrifuged at 13 000 g in 4 °C for 5 min, and stored at −80 °C until use after determination of protein concentrations. Nuclear protein (4 μg) was incubated in 10 μl of binding buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 4% glycerol and 0.05 mg ml−1 poly(dI-dC) (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA) for 10 min at room temperature. Next, 1 μl of 32P-labelled NF-κB oligonucleotide probe (Promega) was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature. For competition assays, 100-fold concentrations of unlabelled oligonucleotides were added to the nuclear proteins. For supershift experiments, antibodies against p50 and p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were added to the nuclear proteins and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. All samples were loaded onto 6% polyacrylamide gels and electrophoresed. Gels were dried and autoradiographed on a Bio-Imaging Analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co.). The density of NF-κB bands was expressed relative to that in the basal state.

Real-time PCR analysis of type IIA and V sPLA2 mRNA expression in HUVECs

Confluent HUVECs in 6-cm gelatin-coated dish were stimulated with 100 ng ml−1 of TNFα (kindly supplied by Dainippon Pharma Co., Osaka, Japan) in M199 medium containing 2% FCS for 4 h, and then total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse-transcribed using ExScript reverse transcriptase (ExScript RT reagent Kit; Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) in the presence of random hexamers at 42 °C for 15 min. Real-time PCR was performed starting with 100 ng cDNA and 0.2 μM concentration of both sense and antisense oligonucleotides (type IIA sPLA2: sense 5′-GAAGTTGAGACCACCCAGCAGAG-3′, antisense 5′-AGCCATAACTGAGTGCGGCTTC-3′; type V sPLA2: sense 5′-CAAACTACGGCTTCTACGGCTGTTA-3′, antisense 5′-CCACGCGAATCTGTATTTGTAGGAC-3′; designed and produced by Takara Bio Inc., in a final volume 20 μl using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq; Takara Bio Inc.). Fluorescence was monitored and analysed in a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Reaction conditions were as follows: denature at 95 °C for 5 s, anneal at 55 °C for 10 s, extend at 72 °C for 10 s for 50 cycles. Analysis of GAPDH mRNA was performed in parallel to normalize gene expression (sense 5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′, antisense 5′-ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT-3′). Results are expressed as 2(Ct GAPDH−Ct type IIA or V sPLA2), where Ct corresponds to the number of cycles needed to generate a fluorescent signal above a predefined threshold.

Western blot analysis of type V sPLA2 protein in HUVECs

Confluent HUVECs in 10-cm gelatin-coated dishes were stimulated with 100 ng ml−1 of TNFα in M199 medium containing 2% FCS for 4 h. Three days later, cells were collected in a 1.5-ml tube. The mixture was centrifuged and the pellet was suspended in 50 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride and 0.1% nonidet P-40). The extracts (20 μg) were separated on 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore Co.). Membranes were blocked in 0.05% Tween-20 Tris-buffered saline (1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 M NaCl and 0.05% Tween-20) with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C in 0.05% Tween-20 Tris-buffered saline containing mouse monoclonal anti-human type V sPLA2 antibody (dilution 1:1000, Cayman Chemical Co.) or anti-human GAPDH antibody (dilution 1:10000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were washed three times with 0.05% Tween-20 Tris-buffered saline and incubated with anti-mouse IgG, peroxidase-linked antibodies (dilution 1:5000 for type V sPLA2, dilution 1:10000 for GAPDH, Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by ECL Plus Chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) and band density analysed using NIH Image analysis software (version 1.55). Type V sPLA2 density was normalized against GAPDH density and expressed relative to that in the basal state.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed by the unpaired Student's t-test for comparisons between two groups and by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's post hoc test for comparisons of multiple groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparative effects of indoxam and thioetheramide-PC on LDL modification by venom sPLA2

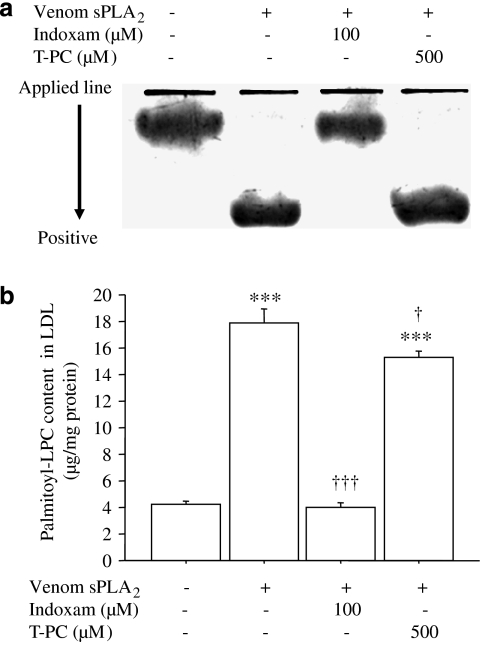

We first compared the inhibitory effect of indoxam on LDL modification by venom sPLA2 with thioetheramide-PC, a structurally modified phospholipid that functions as a competitive, reversible inhibitor of sPLA2. In electrophoresis of LDL (Figure 1a), the electrophoretic mobility was increased by venom PLA2, which was prevented by 100 μM of indoxam (3.1±0.3 mm in native LDL, 10.9±0.8 mm in sPLA2-treated LDL P<0.001, 2.9±0.4 mm in LDL treated with sPLA2 and indoxam; ns, n=4, respectively). However, 1 to 500 μM thioetheramide-PC did not affect the increase of the electrophoretic mobility (9.1±2.2 mm in LDL treated with sPLA2 and 500 μM thioetheramide-PC; ns, n=4). Moreover, palmitoyl-LPC content in LDL was markedly increased by venom sPLA2, as we reported previously (Sonoki et al., 2003), which was completely suppressed by 100 μM of indoxam but only marginally by 500 μM of thioetheramide-PC (Figure 1b, n=4).

Figure 1.

Comparative effects of indoxam and thioetheramide-phosphatidylcholine (PC) on modification of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by venom secretory phospholipase A2 (PLA2). Native LDL was incubated with venom sPLA2 with or without 100 μM indoxam or 500 μM thioetheramide-PC (T-PC) at 37 °C for 2 h. (a) Electrophoretic mobility: four representative sets of electrophoresis. (b) Palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) content in LDL measured by electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Data are mean±s.e.m. of four experiments. ***P<0.001 vs untreated LDL, †P<0.05, †††P<0.001 vs LDL modified by venom sPLA2.

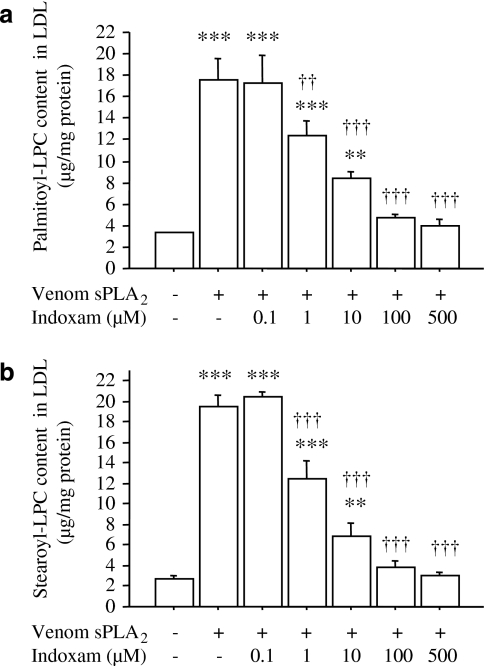

Next, we investigated the effects of various concentrations of indoxam on LPC production in LDL by venom sPLA2 (Figure 2, n=4). Indoxam significantly suppressed the increases in palmitoyl-LPC (Figure 2a) and stearoyl-LPC (Figure 2b) at concentrations of ⩾1 μM. At 100 μM of indoxam, the LPC contents in LDL were not significantly different from those in native LDL. The IC50 of indoxam for suppressing LPC production was 1.2 μM for palmitoyl-LPC and 0.8 μM for stearoyl-LPC.

Figure 2.

Effects of indoxam on palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) (a) and stearoyl-LPC (b) production in native low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by snake venom secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2). Native LDL was incubated with venom sPLA2 in the absence or presence of indoxam at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the LPC content of the LDL was measured by electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Data are mean±s.e.m. of four experiments. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs untreated LDL, ††P<0.01, †††P<0.001 vs LDL modified by venom sPLA2.

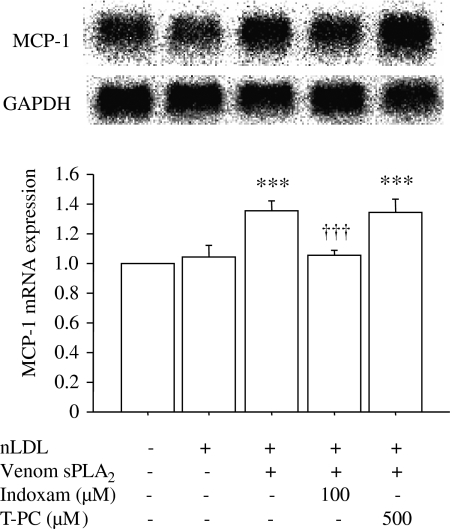

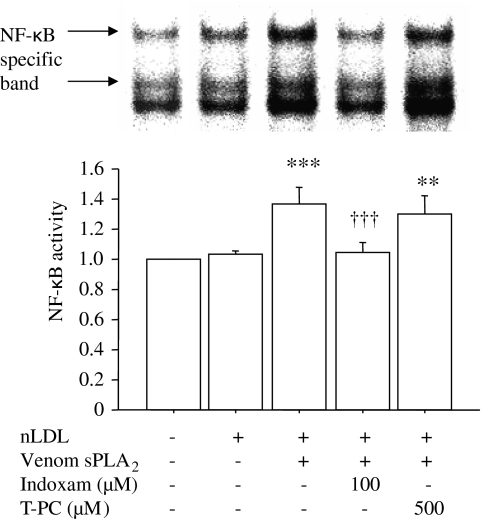

Comparative effects of indoxam and thioetheramide-PC on MCP-1 mRNA expression and NF-κB activity in HUVEC

As indoxam prevented the increase in LPC content in LDL treated with venom sPLA2 (Figure 1b), we investigated its effect on MCP-1 mRNA expression in HUVECs (Figure 3, n=5). MCP-1 mediates the recruitment of mononuclear cells into subendothelial layers, which is an important initial step of atherogenesis. Northern blot analysis showed approximately 1.3-fold increase of MCP-1 mRNA expression in HUVECs incubated with sPLA2-treated LDL compared with HUVECs in the basal state or incubated with native LDL. This enhancement of MCP-1 mRNA expression was prevented by coincubation with 100 μM indoxam but not with 500 μM thioetheramide-PC. As expression of MCP-1 mRNA is regulated by the transcription factor NF-κB, we investigated NF-κB activity in HUVECs by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Figure 4, n=5). LDL treated by venom sPLA2 significantly increased NF-κB activity (1.4-fold) relative to the basal state, and such activation was suppressed by coincubation with 100 μM indoxam, but not with 500 μM thioetheramide-PC.

Figure 3.

Effects of indoxam and thioetheramide-phosphatidylcholine (PC) on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) mRNA expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) after incubation with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) treated with snake venom secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2). Native low-density lipoprotein (LDL) was incubated with venom sPLA2 in the absence or presence of 100 μM indoxam or 500 μM thioetheramide-PC at 37 °C for 2 h. HUVECs were incubated with 100 μg ml−1 of native LDL or LDL modified by venom sPLA2 in the presence or absence of indoxam or thioetheramide-PC (T-PC). MCP-1 mRNA expression was measured by northern blot analysis and expressed relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA expression; the basal state was set as 1.0. Data are mean±s.e.m. of five experiments. ***P<0.001 vs HUVECs incubated with native LDL, †††P<0.001 vs HUVECs incubated with LDL modified by venom sPLA2.

Figure 4.

Effects of indoxam and thioetheramide-phosphatidylcholine (T-PC) on nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activity in human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) after incubation with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) treated with snake venom secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2). Native LDL was modified by venom sPLA2 in the presence or absence of 100 μM indoxam or 500 μM thioetheramide-PC at 37 °C for 2 h. HUVECs were incubated with 100 μg ml−1 of native LDL or LDL modified by venom sPLA2 in the absence or presence of indoxam or thioetheramide-PC. NF-κB activity was measured by electrophoretic mobility shift assay and expressed relative to the basal state, set as 1.0. Data are mean±s.e.m. of five experiments. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs HUVEC incubated with native LDL, †††P<0.001 vs HUVEC incubated with LDL modified by venom sPLA2.

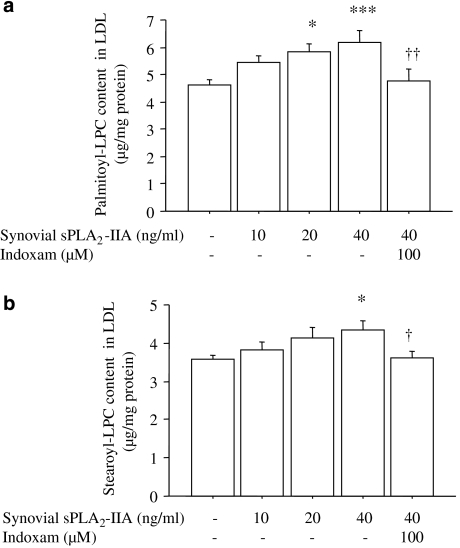

Effect of indoxam on LPC production in LDL by human synovial type IIA sPLA2

As human type IIA sPLA2 was not commercially available at the time of this study, we used synovial fluid obtained from the knee joint of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Such fluid is known to contain large amounts of type IIA sPLA2 (Kramer et al., 1989). When LDL was incubated with human type IIA sPLA2 at 0–40 ng ml−1, the palmitoyl- and stearoyl-LPC contents in LDL showed a mild dose-dependent increase, and 100 μM of indoxam significantly suppressed these increases of LPC contents in LDL treated with 40 ng ml−1 of synovial type IIA sPLA2 (Figure 5, n=6).

Figure 5.

Effects of indoxam on palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) (a) and stearoyl-LPC (b) production in native low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by human synovial type IIA secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2). Native LDL was incubated with human synovial type IIA sPLA2 in the absence or presence of 100 μM indoxam at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, LPC content in the LDL was measured by electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Data are mean±s.e.m. of six experiments. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs untreated LDL, †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 vs LDL modified by 40 ng ml−1 of human synovial type IIA sPLA2.

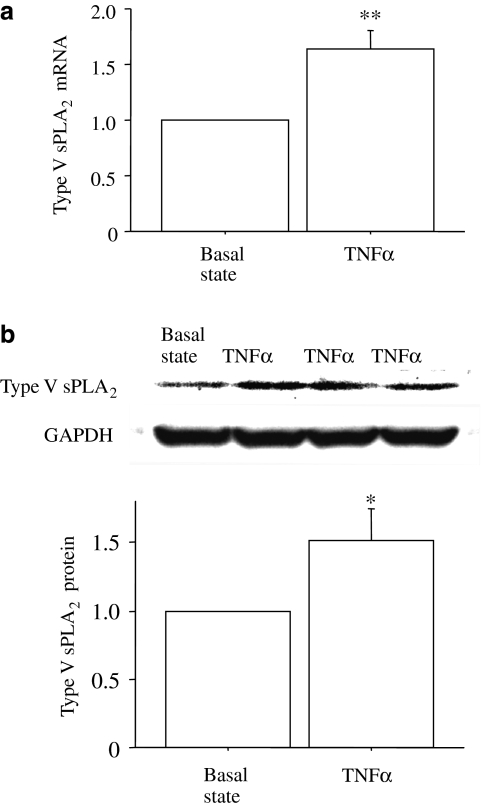

Type V sPLA2 expression in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs

Indoxam inhibits LPC production in LDL by sPLA2 derived from snake venom or by type IIA sPLA2 in human synovial fluid. We next used sPLA2 derived directly from human endothelial cells to approach more closely to the conditions in vascular tissue: HUVECs were stimulated by TNFα for 4 h, based on the TNFα-induced sPLA2 expression in other cells (Andreani et al., 2000). Real-time PCR revealed that TNFα stimulated type V sPLA2 mRNA expression in HUVECs by 1.6-fold relative to the basal state (Figure 6a, n=4), whereas type IIA sPLA2 mRNA was not detected (n=4). Western blot analysis revealed that TNFα-stimulated HUVECs expressed type V sPLA2 protein at a higher level (1.5-fold) than that in unstimulated HUVECs at 3 days after the TNFα stimulation (Figure 6b, n=6).

Figure 6.

Type V secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) mRNA expression (a) and protein expression (b) in human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) after tumour-necrosis factor α (TNFα)-stimulation. Confluent HUVECs were stimulated with 100 ng ml−1 of TNFα for 4 h, and real-time PCR was performed. At 3 days after TNFα-stimulation, western blot analysis was performed and expressed relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein expression. Data are mean±s.e.m. of four experiments for mRNA expression and of six experiments for protein expression. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs basal state.

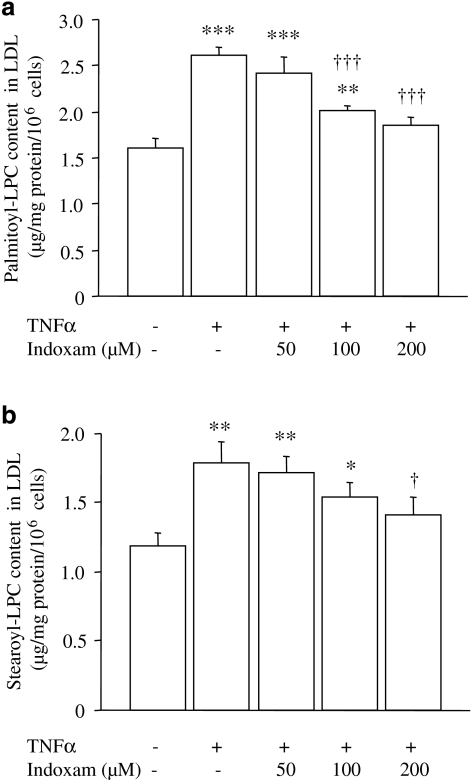

Effect of indoxam on LPC production induced by TNFα-stimulated HUVECs in native or glycoxidized LDL

Native or glycoxidized LDL was incubated with TNFα-stimulated HUVECs with or without indoxam, and then LDL was retrieved from the medium to measure LPC. Native LDL incubated with TNFα-stimulated HUVECs contained more palmitoyl- and stearoyl-LPC compared with LDL incubated with -unstimulated HUVECs (Figure 7, n=5). Coincubation with indoxam reduced the LPC content dose dependently, the reduction was statistically significant at 100 μM of indoxam for palmitoyl-LPC and at 200 μM of indoxam for stearoyl-LPC. Glycoxidized LDL contained higher concentrations of palmitoyl- and stearoyl-LPC compared with native LDL (palmitoyl-LPC 4.70±0.24 μg per mg protein per 106 cells; stearoyl-LPC 4.69±0.43 μg per mg protein per 106 cells, n=6, respectively), as we reported previously (Sonoki et al., 2002). TNFα-stimulated HUVECs further increased the LPC content in glycoxidized LDL (palmitoyl-LPC 7.63±0.98 μg per mg protein per 106 cells; stearoyl-LPC 7.64±1.09 μg per mg protein per 106 cells, P<0.01, n=6). Coincubation with indoxam (100 μM) did not significantly reduce palmitoyl- or stearoyl-LPC in LDL (data not shown), whereas at 200 μM, it reduced palmitoyl-LPC (5.15±0.55 μg per mg protein per 106 cells, P<0.05, n=6), but not stearoyl-LPC (5.99±0.39 μg per mg protein per 106 cells, ns, n=6).

Figure 7.

Effects of indoxam on palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) (a) and stearoyl-LPC (b) production in native low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by tumour-necrosis factor α (TNFα)-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC). Native LDL was incubated for 2 h with unstimulated or TNFα-stimulated HUVEC that had been preincubated 1 h earlier with indoxam. LDL was isolated from the medium using density-gradient ultracentrifugation, and LPC content of the LDL was measured by electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and normalized to cell number in each dish. Data are mean±s.e.m. of five experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs native LDL incubated with unstimulated HUVEC, †P<0.05, †††P<0.001 vs native LDL modified by TNFα-stimulated HUVEC.

To investigate the PLA2 activity released into the medium from TNFα-stimulated HUVECs, we measured type IIA sPLA2 in the medium using the ELISA kit (n=10), but it was undetectable (as expected from the results of the PCR experiments). The medium from TNFα-stimulated or unstimulated HUVECs was applied to native LDL for 2 h and then the LPC contents in the retrieved LDL were compared. There was no difference in LPC contents between LDL incubated with the medium from TNFα-stimulated and unstimulated HUVECs (data not shown). These results suggest that sPLA2 was not released into the medium, but was anchored to the cell surface by heparan sulphate proteoglycan (Murakami et al., 1996).

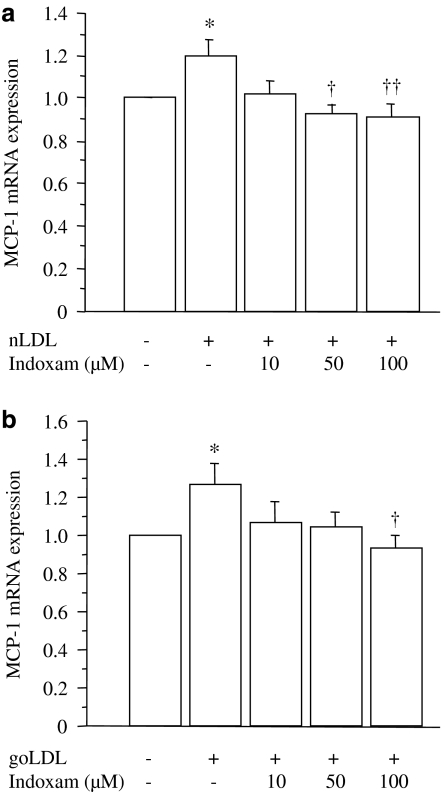

Effect of indoxam on MCP-1 mRNA expression and NF-κB activity in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs incubated with native or glycoxidized LDL

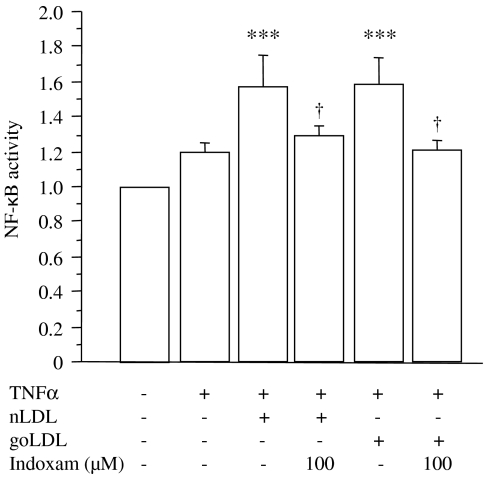

Lastly, we investigated the effects of indoxam on MCP-1 mRNA expression in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs incubated with 100 μg ml−1 of native (Figure 8a, n=4) or glycoxidized LDL (Figure 8b, n=4). The results showed a significant increase in MCP-1 mRNA expression upon the addition of native or glycoxidized LDL compared with TNFα-stimulated HUVECs without LDL. Indoxam significantly prevented this increase at 50 μM with native LDL and at 100 μM of indoxam with glycoxidized LDL. As shown in Figure 9 (n=6), the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB was enhanced by coincubation with native or glycoxidized LDL in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs, whereas 100 μM of indoxam significantly suppressed the activation of NF-κB activity.

Figure 8.

Effects of indoxam on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) mRNA expression after incubation with native low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (a) or glycoxidized LDL (b) in TNFα-stimulated HUVEC. Native (nLDL) or glycoxidized LDL (goLDL) was incubated with tumour-necrosis factor α (TNFα)-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) that had been preincubated 1 h earlier with indoxam. MCP-1 mRNA was measured by northern blot analysis and the mRNA level was corrected by that of the corresponding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA and expressed relative to the value of TNFα-stimulated HUVEC without LDL. Data are mean±s.e.m. of four experiments. *P<0.05 vs TNFα-stimulated HUVEC without LDL, †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 vs TNFα-stimulated HUVEC incubated with LDL alone.

Figure 9.

Effects of indoxam on nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activity after incubation with native or glycoxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in tumour-necrosis factor α (TNFα)-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC). Native (nLDL) or glycoxidized LDL (goLDL) was incubated with TNFα-stimulated HUVEC that had been preincubated 1 h earlier with indoxam. NF-κB activity was measured by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and the activity in the basal state was set as 1.0. Data are mean±s.e.m. of six experiments. ***P<0.001 vs basal state, †P<0.05 vs TNFα-stimulated HUVEC incubated with native or glycoxidized LDL alone.

Discussion and conclusions

In the present study, the indole analogue indoxam, dose dependently prevented LPC production in LDL by venom sPLA2, synovial fluid type IIA sPLA2 and type V sPLA2 in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs. Indoxam also suppressed NF-κB activity and MCP-1 mRNA expression in HUVECs incubated with sPLA2-treated LDL. On the other hand, thioetheramide-PC, a competitive, reversible inhibitor of sPLA2 had no effects on LPC production by venom sPLA2, NF-κB activity or MCP-1 mRNA expression. Thioetheramide-PC is an analogue of PC containing a thioether at the sn-1 position and an amide at the sn-2 position and acts on lipid interfaces. Thioetheramide-PC may be intercalated into the interface and dilute the surface concentrations of the substrate (Yu et al., 1990). There are numerous sPLA2 inhibitors, which are nonspecific or active site-directed competitive inhibitors, although no single compound is highly selective for a single sPLA2 enzyme. Indoxam is known to be the most generally potent sPLA2 inhibitor (Singer et al., 2002).

In vivo indoxam administration prevented endotoxin shock in type IIA sPLA2-deficient C57BL/6J mice (Yokota et al., 1999) and ameliorated cerebral infarction following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats (Yagami et al., 2002). The pharmacokinetic study of indoxam in mice revealed that maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) was approximately 8 μM at 15–30 min after injection of 10 mg kg−1 (Yokota et al., 1999), although a dose of 50 mg kg−1 was needed to prevent a rise in plasma TNFα during endotoxic shock. In vitro treatment with 20 μM indoxam suppressed cytokine and eicosanoid production in macrophages (Saiga et al., 2001; Granata et al., 2005) and neuronal cell death induced by type IIA sPLA2 (Yagami et al., 2001). In the present study, the IC50 of indoxam to prevent palmitoyl-LPC production in LDL by venom sPLA2, which exhibits a more potent hydrolysis of phospholipids than mammalian sPLA2 (Verheij et al., 1980), was 1.2 μM. On the other hand, Degousee et al. (2002) reported that the IC50 of indoxam was 10 nM for recombinant type IIA sPLA2 activity and 40 nM for recombinant type V sPLA2 activity on substrates of [3H]oleate-labelled membranes of Escherichia coli. Although the protein-binding capacity of indoxam has not been determined yet (Dr Kato, Shionogi Co., personal communication), this agent seems to be more potent in experiments using [3H]oleate-labelled E. coli membrane as the substrate.

Type IIA sPLA2 is secreted by a variety of cells including macrophages, and its overexpression in transgenic mice, and specifically in macrophages, causes a marked increase in atherosclerotic lesions (Ivandic et al., 1999; Webb et al., 2003). Moreover, increased serum type IIA sPLA2 levels are a risk factor for coronary artery disease (Boekholdt et al., 2005). However, recent studies showed that type V sPLA2 is important in enzymatic modification of LDL and foam-cell formation in the arterial wall (Wooton-Kee et al., 2004; Boyanovsky et al., 2005) and contributed to the atherosclerotic process in genetically altered mice (Bostrom et al., 2007). In addition, type V sPLA2 is about 20–30 times more potent in phospholipid degradation than type IIA sPLA2 (Gesquiere et al., 2002; Pruzanski et al., 2005). This is in agreement with our findings that synovial type IIA sPLA2 only weakly degraded the PC in LDL. On the other hand, type V sPLA2 preferentially hydrolyses linoleic acid and discriminated against arachidonic acid, in contrast to venom sPLA2 (Gesquiere et al., 2002) and type IIA sPLA2 (Pruzanski et al., 2005). Therefore, the pathological effects of type V sPLA2 are less likely due to the direct stimulation of eicosanoid synthesis, but more to the generation of LPC. sPLA2 is expressed in response to a variety of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 1β and TNFα (van der Helm et al., 2000; Akiba et al., 2001; Hurt-Camejo et al., 2001), and sPLA2 itself directly induces the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules in microvascular endothelium (Beck et al., 2003). In the present study, TNFα enhanced type V sPLA2 expression in HUVECs. Recently, Rosengren et al. (2006) showed type V sPLA2 in the endothelium of advanced atherosclerotic lesions, and reverse-transcription-PCR of cultured human arterial endothelial cells detected the mRNA expression of type V sPLA2 but not type IIA sPLA2. We also failed to detect type IIA sPLA2 mRNA in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs. Higher concentrations of LPC were identified in glycoxidized LDL, which further increased in activated HUVECs. Indoxam dose dependently suppressed the modification of native and glycoxidized LDL by TNFα-stimulated HUVECs. Moreover, indoxam blocked the increase in MCP-1 mRNA expression and NF-κB activity in TNFα-stimulated HUVECs incubated with native or glycoxidized LDL. However, the suppression of MCP-1 mRNA expression was observed at lower doses of indoxam without the suppression of LPC production. These results suggest that indoxam may suppress MCP-1 mRNA expression in activated HUVECs via mechanisms other than the suppression of LPC production. It was reported that types IB and IIA sPLA2 exerted some of their activities independent of their catalytic activity via specific M-type receptors (Ancian et al., 1995; Jaulmes et al., 2005), and indoxam inhibited type IB and X sPLA2 binding to M-type PLA2 receptors in a dose-dependent manner (Yokota et al., 1999, 2000; Granata et al., 2005). In addition, indoxam is not membrane permeable (Mounier et al., 2004). Therefore, further studies are required to ascertain whether indoxam interacts directly with sPLA2 receptors on endothelial cells.

In conclusion, indoxam, a sPLA2 inhibitor, prevented sPLA2-induced production of LPC in native and glycoxidized LDL as well as LDL-associated MCP-1 mRNA expression in HUVECs. Although specific type IIA sPLA2 inhibitors, structurally related to indoxam, had been reported to have no beneficial effects in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Bradley et al., 2005) or severe sepsis (Zeiher et al., 2005), our results suggest that sPLA2 inhibitors, such as indoxam, which suppress LDL modification merit further investigation for the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr N Tayama for providing human synovial fluid samples and Dr T Kato (Shionogi Co.) for valuable suggestions.

Abbreviations

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- sPLA2

secretory PLA2

- TNFα

tumour-necrosis factor α

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Akiba S, Hatazawa R, Ono K, Kitatani K, Hayama M, Sato T. Secretory phospholipase A2 mediates cooperative prostaglandin generation by growth factor and cytokine independently of preceding cytosolic phospholipase A2 expression in rat gastric epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21854–21862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancian P, Lambeau G, Mattei MG, Lazdunski M. The human 180-kDa receptor for secretory phospholipase A2. Molecular cloning, identification of a secreted soluble form, expression, and chromosomal localization. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8963–8970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreani M, Olivier JL, Berenbaum F, Raymondjean M, Bereziat G. Transcriptional regulation of inflammatory secreted phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck GCh, Yard BA, Sculte J, Haak M, van Ackern K, van der Woude FJ, et al. Secreted phospholipase A2 induce the expression of chemokines in microvascular endothelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:731–737. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekholdt SM, Keller TT, Wareham NJ, Juben R, Bingham SA, Day NE, et al. Serum levels of type II secretory phospholipase A2 and the risk of future coronary artery disease in apparently healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:839–846. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000157933.19424.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom MA, Boyanovsky BB, Jordan CT, Wadsworth MP, Taatjes DJ, de Beer FC, et al. Group V secretory phospholipase A2 promotes atherosclerosis: evidence from genetically altered mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:600–606. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000257133.60884.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyanovsky BB, van der Westhuyzen DR, Webb NR. Group V secretory phospholipase A2-modified low density lipoprotein promoted foam cell formation by a SR-A- and CD36-independent process that involves cellular proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32746–32752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JD, Dmitrienko AA, Kivitz AJ, Gluck OS, Weaver AL, Wiesenhutter C, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial of LY333013, a selective inhibitor of group II secretory phospholipase A2, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo G, Hurt-Camejo E, Wiklund O, Bondjers G. Association of apo B lipoproteins with arterial proteoglycans: pathological significance and molecular basis. Atherosclerosis. 1998;139:205–222. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degousee N, Ghomashchi F, Stefanski E, Singer A, Smart BP, Borregaard N, et al. Group IV, V, and X phospholipase A2s in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5061–5073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesquiere L, Cho W, Subbaiah PV. Role of group IIa and group V secretory phospholipase A2 in the metabolism of lipoproteins. Substrate specifications of the enzymes and the regulation of their activities by sphingomyelin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4911–4920. doi: 10.1021/bi015757x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata F, Petraroli A, Boilard E, Bezzine S, Bollinger J, Del Vecchino L, et al. Activation of cytokine production by secreted phospholipase A2 in human lung macrophages expressing the M-type receptor. J Immunol. 2005;174:464–474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagishita S, Yamada M, Shirahase K, Okada T, Murakami Y, Ito Y, et al. Potent inhibitors of secretory phospholipase A2: synthesis and inhibitory activities of indolizine and indene derivatives. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3636–3658. doi: 10.1021/jm960395q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Gubitosi-Klug RA, Collons BJ, Gross RW. Alterations in individual molecular species of human platelet phospholipids during thrombin stimulation: electrospray ionization mass spectrometry-facilitated identification of the boundary conditions for the magnitude and selectivity of thrombin-induced platelet phospholipid hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5822–5832. doi: 10.1021/bi952927v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanasaki K, Yamada K, Yamamoto S, Ishimoto Y, Saiga A, Ono T, et al. Potent modification of low density lipoprotein by group X secretory phospholipase A2 is linked to macrophage foam cell formation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29116–29124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt-Camejo E, Andersen S, Standal R, Rosengren B, Sartipy P, Stadberg E, et al. Localization of nonpancreatic secretory phospholipase A2 in normal and atherosclerotic arteries. Activity of the isolated enzyme on low-density lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:300–309. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G, Peilot H, Oorni K, Kovanen P. Phospholipase A2 in vascular disease. Circ Res. 2001;89:298–304. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.095598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivandic B, Castellani LW, Wang XP, Qiao JH, Mehrabian M, Navab M, et al. Role of group II secretory phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis: 1. Increased atherogenesis and altered lipoproteins in transgenic mice expressing group IIa phospholipase A2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1284–1290. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.5.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2745–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaulmes A, Janvier B, Andreani M, Raymondjean M. Autocrine and paracrine transcriptional regulation of type IIA secretory phospholipase A2 gene in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1161–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000164310.67356.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzny MA, Duncan LA, Merritt MV, Epps DE. Rapid separation of lipid classes in high yield and purity using bonded phase columns. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RM, Hession C, Johansen B, Hayes G, McGray P, Chow EP, et al. Structure and properties of a human non-pancreatic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5768–5775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo I, Murakami M. Phospholipase A2 enzymes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:3–58. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier CM, Ghomashchi F, Lindsay MR, James S, Singer AG, Parton RG, et al. Arachidonic acid release from mammalian cells transfected with human groups IIA and X secreted phospholipase A2 occurs predominantly during the secretory process and with the involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25024–25038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Kudo I. New phospholipase A2 isozymes with a potential role in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14:431–436. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Kudo I. Secretory phospholipase A2. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:1158–1164. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Nakatani Y, Kudo I. Type II secretory phospholipase A2 associated with cell surfaces via C-terminal heparin-binding lysine residues augments stimulus-initiated delayed prostaglandin generation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30041–30051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuzil J, Upston JM, Witting PK, Scott KF, Stocker R. Secretory phospholipase A2 and lipoprotein lipase enhance 15-lipoxygenase-induced enzymic and nonenzymic lipid peroxidation in low-density lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9203–9210. doi: 10.1021/bi9730745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruzanski W, Lambeau L, Lazdunski M, Cho W, Kopilov J, Kuksis A. Differential hydrolysis of molecular species of lipoprotein phosphatidylcholine by groups IIA, V and X secretory phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1736:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren B, Peilot H, Umaerus M, Jonsson-Rylander AC, Mattson-Hulten L, Hallberg C, et al. Secretory phospholipase A2 group V: lesion distribution, activation by arterial proteoglycans, and induction in aorta by a Western diet. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1421–1422. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000221231.56617.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiga A, Morioka Y, Ono T, Nakano K, Ishimoto Y, Arita H, et al. Group X secretory phospholipase A2 induces potent productions of various lipid mediators in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1530:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AG, Ghomashchi F, Le Calvez C, Bollonger J, Bezzine S, Rouault M, et al. Interfacial kinetic and binding properties of the complete set of human and mouse groups I, II, V, X, and XII secreted phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48535–48549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoki K, Yoshinari M, Iwase M, Iino K, Ichikawa K, Ohdo S, et al. Glycoxidized low-density lipoprotein enhances MCP-1 mRNA expression in HUVEC. Relation to lysophosphatidylcholine contents and inhibition by nitric oxide donor. Metabolism. 2002;51:1135–1142. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoki K, Iwase M, Iino K, Ichikawa K, Ohdo S, Higuchi S, et al. Atherogenic role of lysophosphatidylcholine in low-density lipoprotein modified by phospholipase A2 and in diabetic patients: Protection by nitric oxide donor. Metabolism. 2003;52:308–314. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Helm HA, Aarsman AJ, Janssen MJ, Neys FW, van den Bosch H. Regulation of the expression of group IIA and group V secretory phospholipase A2 in rat mesangial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1484:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheij HM, Boffa MC, Rothen C, Bryckaert MC, Verger R, de Haas GH. Correlation of enzymatic activity and anticoagulant properties of phospholipase A2. Eur J Biochem. 1980;112:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira OV, Laranjinha JA, Madeira VM, Almeida LM. Rapid isolation of low density lipoproteins in a concentrated fraction free from water-soluble plasma antioxidants. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:2715–2721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T, Ueda K, Asakura K, Hori Y. Deterioration of axotomy-induced neurodegeneration by group IIA secretory phospholipase A2. Brain Res. 2001;917:230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02994-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T, Ueda K, Asakura K, Hata S, Kuroda T, Sakaeda T, et al. Human group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 induces neuronal cell death via apoptosis. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:114–126. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota Y, Hanasaki K, Ono T, Nakazato H, Kobayashi T, Arita H. Suppression of murine endotoxic shock by sPLA2 inhibitor, indoxam, through group IIA sPLA2-independent mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1438:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota Y, Higashino K, Nakano K, Arita H, Hanasaki K. Identification of group X secretory phospholipase A2 as a natural ligand for mouse phospholipase A2 receptor. FEBS Lett. 2000;478:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Deems RA, Hajdu J, Dennis EA. The interaction of phospholipase A2 with phospholipid analogues and inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2657–2664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb NR, Bostrom MA, Szilvassy SJ, van der Westhuyzen DR, Daugherty A, de Beer FC. Macrophage-expressed group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 increases atherosclerotic lesion formation in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:263–268. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000051701.90972.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooton-Kee CR, Boyanovsky BB, Nasser MS, de Villiers WJ, Webb NR. Group V sPLA2 hydrolysis of low-density lipoprotein results in spontaneous particle aggregation and promotes macrophage foam cell formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:762–767. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122363.02961.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski A, Macphee C. Role of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis: biology, epidemiology, and possible therapeutic target. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:923–931. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160551.21962.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiher BG, Steingrub J, Laterre PF, Dmitrienko A, Fukiishi Y, Abraham E, EZZI Study Group LY315920NA/S-5920, a selective inhibitor of group IIA secretory phospholipase A2, fails to improve clinical outcome for patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1741–1748. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000171540.54520.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]