Abstract

Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is an abundant copper/zinc enzyme found in the cytoplasm that converts superoxide into hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen. Tetrathiomolybdate (ATN-224) has been recently identified as an inhibitor of SOD1 that attenuates FGF-2- and VEGF-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in endothelial cells. However, the mechanism for this inhibition was not elucidated. Growth factor (GF) signaling elicits an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), which inactivates protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) by oxidizing an essential cysteine residue in the active site. ATN-224-mediated inhibition of SOD1 in tumor and endothelial cells prevents the formation of sufficiently high levels of H2O2, resulting in the protection of PTPs from H2O2-mediated oxidation. This, in turn, leads to the inhibition of EGF-, IGF-1-, and FGF-2-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Pretreatment with exogenous H2O2 or with the phosphatase inhibitor vanadate abrogates the inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by ATN-224 or SOD1 siRNA treatments. Furthermore, ATN-224-mediated SOD1 inhibition causes the down-regulation of the PDGF receptor. SOD1 inhibition also increases the steady-state levels of superoxide, which induces protein oxidation in A431 cells but, surprisingly, does not oxidize phosphatases. Thus, SOD1 inhibition in A431 tumor cells results in both prooxidant effects caused by the increase in the levels of superoxide and antioxidant effects caused by lowering the levels of H2O2. These results identify SOD1 as a master regulator of GF signaling and as a therapeutic target for the inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cancer, redox, tetrathiomolybdate, ATN-224

Tetrathiomolybdate (TM) is a copper-binding drug that has been shown to have efficacy as an anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor agent in several mouse models of cancer (1–8) and has been tested in several oncology clinical trials (9–11). ATN-224 is a second-generation analogue of TM, which is currently being evaluated in several phase II trials in cancer patients (11). The copper dependent enzyme superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) has recently been identified as the main target for the anti-angiogenic activity of ATN-224 (1). SOD1 belongs to the SOD family of enzymes, which catalyze the dismutation of superoxide into H2O2 and oxygen, thus maintaining low steady-state levels of superoxide (≈10−10 M) (12–14). Because excess superoxide is toxic and superoxide has very poor membrane permeability, SOD is ubiquitously present in different organelles within the cell (12). SOD1 is present in the cytosol, nucleus and the intermembrane space of mitochondria; SOD2, a manganese containing enzyme, is present in the mitochondrial matrix, and ecSOD (SOD3), a secreted copper containing protein, is found in the extracellular matrix of tissues (12). The SOD family of enzymes has been extensively studied. Although the SOD2 knock-out is lethal in mice (15), the SOD1 and ecSOD knock out phenotypes are generally considered mild (16–20). CuZnSOD (SOD1) knock out mice are usually healthy although female mice may have decreased fertility (17). More recently, SOD1−/− mice were found to have an elevated susceptibility to liver tumors (18) as a consequence of a high rate of DNA mutations that occur at an early age (2–6 months) (19). SOD1 knock-down by siRNA has been shown to induce senescence in fibroblasts (21).

We showed that ATN-224 inhibits proliferation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and induces apoptosis in MM1S multiple myeloma tumor cells (1). SOD1 inhibition by ATN-224 increased the steady-state levels of superoxide in HUVEC (1). Furthermore, ATN-224 treatment of HUVEC abolished FGF-2 and VEGF-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (1). We hypothesized that the inhibition of ERK phosphorylation was due to an imbalance in ROS, which have been known to affect multiple signaling pathways (22–26). However, the precise mechanism by which inhibition of SOD1 abolishes ERK phosphorylation was not determined. Signaling regulation by ROS generally involves the reversible oxidation of Cys residues in target proteins leading to subsequent alteration of activity (22–26). The activity of several growth factors (GF) e.g., EGF, IGF-1, PDGF, and VEGF is redox regulated by a mechanism in which GF binding to its receptor tyrosine kinase activates production of ROS, which in turn inactivates phosphatases, shifting the balance within cells toward phosphorylation and allowing kinase cascades to propagate (22–26). All protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) have an essential cysteine (Cys) residue in their active sites that is readily oxidized because of a lower pKa than normally found for the Cys thiol (23, 24). The source and nature of the ROS involved in this process are not clearly defined; however, it is suspected that either superoxide or H2O2, produced by superoxide dismutation, or both oxidize PTPs.

Here, we present evidence showing that SOD1 is essential for growth factor signaling in endothelial and tumor cells. Inhibition of SOD1 protects PTPs from oxidation by preventing the formation of H2O2. This, in turn, inhibits ERK phosphorylation in cells stimulated with EGF, FGF-2, or IGF-1. Paradoxically, SOD1 inhibition induces both prooxidant effects mediated by an excess superoxide and antioxidant effects caused by a decrease in H2O2. These results further validate SOD1 as a therapeutic target for the inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth.

Results

SOD1 Is the Target for ATN-224, and Its Inhibition Attenuates EGF- and IGF-1-Mediated ERK1/2 Phosphorylation in Cells.

The effects of ATN-224 on SOD1 inhibition, proliferation, and signaling in HUVEC and MM1S cells have been demonstrated to be maximal after 48 h of incubation (1). Thus, the standard treatment of cells with ATN-224 in signaling studies is for 48 h in full growth media. The IC50 for ATN-224 inhibition of SOD1 in A431 cells was 185 ± 65 nM (n = 5), and, for the inhibition of proliferation, it was 4.5 ± 0.40 μM (n = 6) (Fig. 1A), indicating that SOD1 must be completely inhibited to achieve antiproliferative effects as has already been shown for HUVEC (1). As expected, SOD1 siRNA did not have antiproliferative effects by itself, because it did not inhibit SOD1 activity completely (≈70% inhibition). However, it had additive effects with ATN-224 (Fig. 1B). As shown for HUVEC (1), the SOD mimetic Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) abrogated the antiproliferative effects of ATN-224 in A431 cells (Fig. 1C). Altogether, these results (Fig. 1 B and C) confirm that SOD1 is the target of ATN-224's antiproliferative activity. Because ATN-224 treatment of HUVEC abolished FGF-2, and VEGF mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (1), we evaluated whether ATN-224 treatment would inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation in tumor cells. We chose GF that are known to be redox regulated, such as EGF and IGF-1 (22, 23, 25, 27), and cell lines known to be sensitive to the particular GF. ATN-224 treatment decreased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (pERK) mediated by EGF in A431, but not in A549 cells (Fig. 1D). ATN-224 treatment at the concentrations used in this study completely inhibits SOD activity in all cell types evaluated (data not shown). Supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A shows decreases in pERK with increasing concentrations of ATN-224 in EGF-stimulated A431 cells. ATN-224 treatment also inhibited pERK in HT-29 cells stimulated with IGF-1 (Fig. 1E) and triggered apoptosis in both A431 and HT-29 (Fig. S1B). Some tumor cells, such as A549 cells, were resistant to ATN-224-mediated inhibition of pERK (Fig. 1D), and apoptosis was not induced in these cells. However, ATN-224 treatment did inhibit proliferation in these cells (data not shown). If the signaling effects mediated by ATN-224 were due to the inhibition of SOD1, then SOD1 siRNA should replicate the results. Treatment with SOD1 siRNAs, but not control siRNA, attenuated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in A431 cells stimulated with EGF (Fig. 1F), suggesting that ATN-224 effects on signaling are the result of SOD1 inhibition. ATN-224-mediated inhibition of pERK was also observed in IGF-1-induced MM1S or EGF-stimulated fibroblasts (HDFa) (Fig. S1 C and D). Furthermore, ATN-224 also inhibited the high basal levels of pERK in U87 glioblastoma cells (Fig. S1E). Therefore, interference with SOD1 has antiproliferative/antiproapoptotic activity and inhibits EGF and IGF-1 stimulation of pERK in several cell lines in vitro.

Fig. 1.

SOD1 is the target for ATN-224 and SOD1 inhibition attenuated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 upon GF stimulation. (A) A431 cells were treated with ATN-224 for 48 h, and proliferation (MTT assay) (inverted filled triangles) and SOD1 activity (filled circles) were determined. (B) A431 cells were transfected with SOD1 siRNA (74) (filled circles), control siRNA (inverted filled triangles), or nontransfected (open circles) and plated on a 96-well plate, and proliferation was determined as in A. (C) A431 proliferation (MTT assay) was measured in cells treated with MnTBAP either alone (filled bars) or with 30 μM ATN-224 (empty bars). (D) A431 or A549 cells were treated with ATN-224 for 48 h. Then, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of EGF for 10 min and lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out. (E) HT-29 cells were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h. Then, cells were stimulated with IGF-1 for 10 min and lysed, and ELISAs were carried out. (F) A431 cells were transfected with different SOD1 siRNA [74, 75, 76, and all three (comb.)] or control siRNA (C) for 48 h. Then, the cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of EGF for 10 min and lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out.

SOD1 Inhibition Attenuates Phosphorylation of the EGF Receptor (EGFR) and the IGF-1 Receptor (IGF-1R) and Down-Regulates the PDGFβ Receptor (PDGFR).

To investigate at which level the inhibition of the MAPK pathway was taking place, the phosphorylation of the EGFR at Tyr 1173 and of IGF-1R at Tyr-1135/1136 were examined after ATN-224 treatment in EGF or IGF-1-treated cells. Maximal phosphorylation of the receptors occurred at 100 ng/ml for EGF and 20 ng/ml for IGF-1. Phosphorylation of the EGFR (Fig. 2A and B) and IGF-1R (Fig. 2C) after stimulation with EGF and IGF-1, respectively, were decreased by ATN-224 treatment. Furthermore, ATN-224 treatment of A431 cells attenuated EGF-mediated phosphorylation of a subset of Tyr residues (992, 1045, 1068, and 1173) in the EGFR (Fig. 2B), some of which have been known to mediate signaling in the MAPK pathway (28) and to be activated by ROS (29). These results suggest that the down-regulation of pERK through SOD1 inhibition occurs at the level of the receptor tyrosine kinase, although other points of inhibition in the cascade cannot be ruled out. The PDGF pathway is also known to be regulated by ROS (30, 31). The possible effects of ATN-224 on PDGF signaling were investigated in U87 glioblastoma cells, which overexpress the PDGFβ receptor (PDGFR). ATN-224 treatment of U87 cells caused the down-regulation of PDGFR protein expression but not of the EGFR protein (Fig. 2D), indicating the potential for significant downstream inhibitory effects. In summary, SOD1 inhibition by ATN-224 results in the attenuation of the EGF and IGF-1 pathways and a considerable decrease in PDGFR protein, which may have implications for tumor cell growth and survival.

Fig. 2.

SOD1 inhibition attenuates GF receptor phosphorylation. (A) A431 cells were incubated with the indicated amounts of ATN-224 for 48 h. Then, cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml of EGF for 10 min and lysed and Western blot analyses were carried out, probing for EGFR and pEGFR (Tyr-1173). (B) A431 cells were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h. Then, cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml of EGF for 10 min and lysed and Western blot analyses were carried out, probing for pEGFR (Tyr-845, -992, -1045, -1068, -1086, -1148, and -1173) and tubulin. The appropriate bands were quantitated and normalized to tubulin. (C) HT-29 cells were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h. Then, cells were stimulated with 20 ng/ml of IGF-1 and lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out, probing for IGF-1Rβ or pIGF-1Rβ (Tyr-1135/1136). (D) U87 cells were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h in full growth media. Then, cells were lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out.

SOD1 Inhibition Increases the Steady-State Levels of Superoxide Inducing Prooxidant Effects.

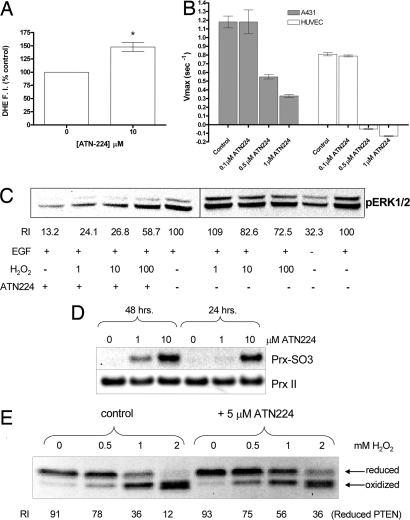

We then investigated the mechanism by which SOD1 inactivation leads to inhibition of the MAPK pathway, using primarily A431 cells ± EGF. HUVEC ± FGF-2 were also used in some experiments as a model of a primary cell line. Similar to what we reported for HUVEC (1), 10 μM ATN-224 treatment of A431 cells for 48 h increased the steady-state levels of superoxide (48 ± 8.5%), as determined by using the superoxide-sensitive fluorescence dye dihydroethidium (DHE) (Fig. 3A). To confirm this increase, aconitase activity was measured. Levels of aconitase activity have been used as an indirect measurement of superoxide concentration, because superoxide inactivates the [4Fe-4S] cluster of aconitase (32). The activity of cytosolic aconitase was inhibited in ATN-224-treated A431 and HUVEC (Fig. 3B), in agreement with the observed increase in superoxide shown in Fig. 2A and ref. 1. ATN-224 treatment of A431 cells also increased the levels of protein carbonylation when compared with control cells (Fig. S2), as would be expected if superoxide levels are higher than normal.

Fig. 3.

ATN-224 treatment of A431 cells alters the redox state, which seems responsible for the inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. (A) A431 cells were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h in full growth media. Then, cells were treated with dihydroethidium (DHE) at 1.6 μM in PBS for 15 min followed by extensive washing and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the levels of superoxide (n = 3; *, P < 0.001). (B) A431 cells were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h in full growth media. Then, cytosolic aconitase activity was measured (average of n = 3 ± standard deviation) as described in Materials and Methods. (C) A431 cells were incubated with 7 μM ATN-224 for 48 h in full growth media. Then, the cells were treated with 1, 10, or 100 μM of H2O2 for 0.5 h in cell media containing 0.5% FBS, washed, and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml of EGF. The numbers under the bands [relative intensity (RI)] represent the intensity of the pERK bands normalized to tubulin. (D) A431 cells were treated with ATN-224 for 24 or 48 h, cells were lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out, probing with antibodies against Prx II and Prx-SO3. The later recognizes the oxidized forms of Prx I to IV. (E) A431 were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h in full growth media. Then, cells were treated with H2O2 in cell media containing 0.5% FBS for 10 min. After that, cells were washed, lysed in the presence of NEM, run on a nonreducing SDS/PAGE, transferred, and probed with antibodies against PTEN. When PTEN is oxidized by H2O2, it runs as a faster species than reduced PTEN in a SDS/PAGE. The numbers under the bands (RI) represent the intensity of reduced PTEN bands normalized to tubulin.

SOD1 Inhibition Decreases the Levels of H2O2, Which Attenuates pERK in GF-Stimulated Cells.

Because the steady-state levels of superoxide increase on ATN-224 inhibition of SOD1, the levels of H2O2 may correspondingly decrease. In turn, reduced H2O2 levels could result in the attenuation of GF signaling by preventing the oxidation and inactivation of PTPs. The oxidation of dichlorofluorescein (H2DCFDA) to the highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) is a commonly used method to measure H2O2 levels (33–34). Using H2DCFDA, we determined that the basal levels of H2O2 decreased by 28% (n = 3, P = 0.012) in ATN-224 (5 μM)-treated A431 cells. To corroborate that ATN-224-mediated inhibition of SOD1 was lowering the levels of H2O2, we used an indirect approach. If the observed effects of ATN-224 in signaling are mediated by a decrease in hydrogen peroxide, adding exogenous H2O2 to ATN-224-treated cells should reverse the ATN-224-mediated effects on signaling. Thus, the effects of combined SOD1 inhibition and H2O2 treatment on GF-stimulated ERK/12 phosphorylation in HUVEC and A431 cells were evaluated. Treatment of A431 cells for 48 h with ATN-224 (7 μM) decreased the level of EGF-induced pERK by ≈87% (Fig. 3C), consistent with the data presented in Fig. 1D. However, when H2O2 (1, 10, and 100 μM) was added to ATN-224 (7 μM)-treated A431 cells 0.5 h before stimulation with EGF, the inhibition of ERK phosphorylation was decreased to 75.9, 73.2, and 41.3%, respectively, suggesting that the addition of H2O2 treatment was able to reverse the effects of ATN-224 (Fig. 3C). As a control, H2O2 treatment by itself under the conditions described above had minimal effects on the EGF-stimulated increase in pERK in A431 cells (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained when using SOD1 siRNA in A431 cells (data not shown) and in ATN-224-treated HUVEC (Fig. S3). In contrast to A431, H2O2 treatment of HUVEC only modestly reversed ATN-224-mediated down-regulation of FGF-2-induced pERK. Higher H2O2 concentrations and longer incubation times were deleterious to HUVEC survival, precluding a clearer result. To rule out that ATN-224 treatment was increasing peroxidase activity and causing a reduction in H2O2 concentration, the levels of peroxiredoxins (Prx) were evaluated in A431 cells. Prx are peroxidases that modulate the levels of H2O2 during GF signaling (25, 31). The levels of Prx II (Fig. 3D), Prx I, and 2-Cys-Prx family (data not shown) proteins did not change significantly upon ATN-224 treatment after either 24 or 48 h. In addition, the levels of catalase and glutathione peroxidase did not increase as determined by Western blotting in ATN-224-treated A431 cells (data not shown). Finally, the amount of oxidized and therefore inactive Prx increased significantly in ATN-224-treated A431 cells as determined by Western blot, using an antibody that is specific for the oxidized forms of Prx I to IV (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the apparent decrease in H2O2 observed upon ATN-224 treatment was not due to an increase in peroxidase activity. These results argue that the levels of H2O2 are lowered in ATN-224-treated HUVEC and A431 cells, resulting in the attenuation of the GF-stimulated MAPK pathway.

To further confirm that the effects of SOD1 inhibition in GF-mediated MAPK signaling were due to a lack of sufficiently high concentration of H2O2, the levels of oxidized and reduced PTEN were measured in A431 cells exposed to H2O2. PTEN is a well studied redox regulated lipid phosphatase (35) that, when oxidized, forms a disulfide bond between the active site Cys residue and a vicinal Cys residue. This alters the mobility of PTEN when separated by SDS/PAGE (35), which makes it an ideal sensor of changes in the redox status of proteins within the cell. A431 cells were treated with H2O2 at 0.5 to 2 mM for 10 min to oxidize most of the PTEN present (≈90% at 2 mM) (Fig. 3E). However, in ATN-224-treated cells (5 μM for 48 h), only ≈64% of PTEN was oxidized at the highest H2O2 concentration (Fig. 3E), indicating that higher levels of H2O2 were needed to oxidize and inactivate PTEN in ATN-224-treated cells than in control cells. This is consistent with the results presented above, which indicate decreased steady-state levels of H2O2 in ATN-224-treated A431 cells.

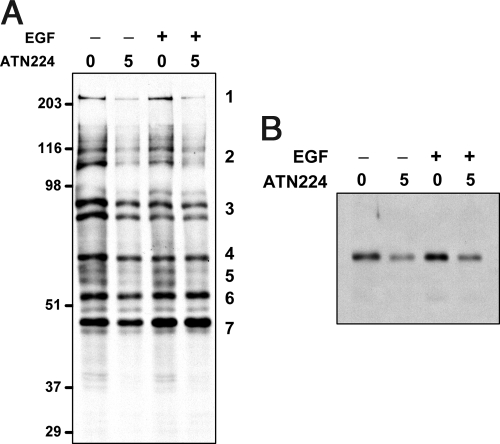

SOD1 Inhibition Protects PTP1B from H2O2-Mediated Oxidation.

The results shown in Fig. 3E also suggest that SOD1 inhibition may result in the protection of PTPs from GF-mediated oxidation. PTP1B, which is known to dephosphorylate the EGFR and IGF-1R, is oxidized upon EGF or IGF-1 stimulation (24, 27). Furthermore, ATN-224 blocks EGF and IGF-1 signaling (Fig. 1), making PTP1B a candidate PTP to be protected by SOD1 inhibition during GF signaling. Thus, two different methods were used to interrogate the redox status of PTP1B in control versus ATN-224-treated A431 cells (Fig. 4 and Fig. S4). First, using an experimental approach in which oxidized Cys incorporate a biotin moiety, several proteins in A431 cells (bands 1, 2, and 5) were found to be protected from oxidation by ATN-224 (decreased signal), whereas others (bands 3, 4, 6, and 7) were not (Fig. 4A). Stimulation of A431 cells with EGF oxidizes PTP1B, reaching a maximum after 2–5 min (Fig. S4A). After 5 min of EGF stimulation, ATN-224 treatment protected PTP1B from EGF-mediated oxidation in A431 cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, when a maleimide-biotin reagent that selectively reacts with free sulfhydryl groups was used, more biotin was incorporated in the PTP1B band in ATN-224-treated A431 cells (69 ± 39% increase, n = 3, P < 0.01) than in control cells, indicating the presence of higher levels of reduced PTP1B (Fig. S4 B and C). Likewise, the levels of reduced PTP1B in ATN-224-treated HUVEC were 86 ± 50% (n = 3, P < 0.05) higher than control (Fig. S4C). On the contrary, in A549, in which ATN-224 treatment does not reduce EGF-stimulated pERK (Fig. 1D), there was no increase in biotin incorporation (data not shown). Thus, paradoxically, SOD1 inhibition results in antioxidant effects on PTPs likely due to a decrease in H2O2 and prooxidant effects possibly due to an increase in superoxide (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S2).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of SOD1 by ATN-224 reduces the levels of oxidized PTP1B and other proteins. (A) A431 cells treated with 5 μM ATN-224 for 48 h were lysed in the presence of iodoacetic acid to block reduced Cys residues, buffer exchanged, reduced with DTT and reacted with maleimide-biotin so that originally oxidized proteins would acquire a biotin label. Proteins were then IP with streptavidin–agarose (SA) followed by Western blot analysis, which was probed for biotin. (B) A431 cells were treated with 5 μM ATN-224 for 48 h and then stimulated with 100 ng/ml of EGF for 5 min and treated as in B, and biotinylated proteins were then immunoprecipitated with SA followed by Western blot analysis, which was probed for PTP1B.

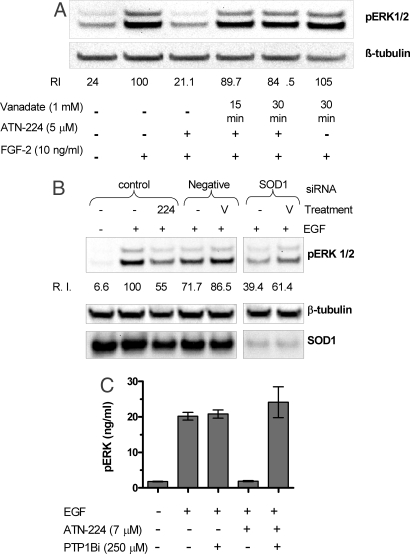

PTP Inhibitors Antagonize the Attenuation of pERK Caused by SOD1 Inhibition in GF-Stimulated Cells.

Small-molecule inhibitors of PTPs were used to confirm the hypothesis that ATN-224 effects on GF signaling are mediated through the protection of PTPs from oxidation. Orthovanadate is a well characterized broad spectrum inhibitor of PTPs that has been widely used to probe the role of PTPs in signaling (36, 37). HUVEC were treated with orthovanadate 15 or 30 min before stimulation with FGF-2. Both orthovanadate pretreatments abrogated the ATN-224-mediated inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in FGF-2-treated HUVEC while having no effect in combination with FGF-2 in control cells (Fig. 5A). Likewise, orthovanadate pretreatment antagonized the inhibitory effects of SOD1 siRNA on ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5B) in EGF-stimulated A431 cells. Orthovanadate pretreatment increased the levels of pERK in both SOD1 siRNA and control (Fig. 5B). However, the change for the control siRNA was only 21%, whereas, for SOD1, siRNA the increase was 56% (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained in repeat experiments (n = 3). Consistent with the hypothesis that PTPs, and specifically PTP1B, are a target of SOD1 inhibition, addition of a specific inhibitor of PTP1B (PTP1Bi) in ATN-224-treated A431 cells 3 h before GF stimulation abrogated the effects of ATN-224 on EGF-stimulated pERK (Fig. 5C). This inhibitor has been shown to be specific for PTP1B (38). However, it cannot be ruled out that other phosphatases were also inhibited. Taken together, these findings suggest that SOD1 inhibition provides protection against oxidation of PTPs during GF signaling resulting in the attenuation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

PTP inhibitors block ATN-224 and SOD1 siRNA-mediated attenuation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. (A) HUVEC were incubated with ATN-224 for 48 h in full growth media. Cells were then treated with orthovanadate for either 15 or 30 min followed by stimulation with FGF-2 and lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out. The numbers under the bands (relative intensity) represent the intensity of the pERK bands normalized to tubulin. (B) A431 cells were treated either with 7 μM ATN-224 (224) for 48 h or transfected with SOD1 siRNA or control siRNA for 48 h. Cells were then treated with 1 mM orthovanadate (V) for 15 min or not treated before stimulation with 10 ng/ml of EGF for 10 min. Cells were lysed, and Western blot analyses were carried out. V, orthovanadate treatment; 224, ATN-224 treatment. (C) A431 cells were treated with ATN-224 for 48 h and exposed to a PTP1B inhibitor 1 h before being stimulated with 10 ng/ml of EGF for 10 min. Cells were lysed, and ELISAs were carried out, probing for ERK1/2, pERK. The graph shows means ± SD (n = 3) of pERK normalized to ERK1/2.

Discussion

The main findings of this work are (Fig. S5) that (i) SOD1 inhibition causes both prooxidant and antioxidant effects, (ii) excess superoxide does not oxidize PTP1B, and (iii) SOD1 plays an essential role in GF-mediated MAPK signaling by mediating the transient oxidation and inactivation of PTPs. These conclusions are drawn from studies performed with several tumor cell lines, primary endothelial cells and fibroblasts. In A549 cells, SOD1 inhibition did not attenuate GF signaling. This cell line contains a mutated constitutively active form of Ras that is known to regulate ROS (26) and, as such, may overcome the effects of SOD1 inhibition. Moreover, mutated Ras constitutively activates the MAPK pathway, which may also oppose the effects of SOD1 inhibition of ERK phosphorylation. Finally, it is presently unclear how ATN-224 treatment down-regulates the levels of the PDGF receptor in U87 cells (Fig. 2D).

Although the type and origin of ROS that inactivates PTPs during GF signaling has not been unequivocally identified, it is generally accepted that GF binding to its receptor increases levels of superoxide, which is then dismutated into H2O2 (22, 23, 26). Because superoxide can dismutate non-enzymatically at a fast rate (5 × 105 M−1·s−1) (12, 14) and because superoxide can potentially oxidize PTPs (39), the possible contribution of SOD1 to this process has been neglected. However, the results presented here demonstrate that superoxide does not oxidize PTP1B and that the spontaneous dismutation of superoxide is insufficient to generate the levels of H2O2 needed for PTP inactivation. Therefore, enzymatically active SOD1 is required for PTP oxidation during GF signaling. Our results show that SOD1 inhibition protects PTP1B from oxidation in A431 cells and HUVEC. This protection occurred under basal conditions (Fig. S4) and immediately after EGF stimulation (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the effects of SOD1 inactivation on ERK phosphorylation were dependent on having active PTPs. This was demonstrated by reversing the effects of ATN-224 or SOD1 siRNA on GF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation by two different approaches: by adding H2O2 exogenously, which should oxidize and inactivate PTPs, and by treating with two different PTP inhibitors, orthovanadate and a specific PTP1B inhibitor. PTP1B is known to dephosphorylate EGFR and IGF-1R (24, 27, 28), which are also targets for SOD1 inhibition in A431 and HT-29 cells. Therefore, PTP1B was a candidate PTP responsible for the SOD1-mediated effects on the GF-stimulated MAPK pathway. We demonstrated (Fig. 5C) that a pharmacological inhibitor of PTP1B blocked the effects of ATN-224 on ERK phosphorylation in response to EGF stimulation. Although it cannot be ruled out that the PTP1B inhibitor cross-reacted with other PTPs, this result suggested an important role for PTP1B as an effector of SOD1 inhibition, which is in agreement with the partial inhibition observed at the level of the GF tyrosine kinase receptor by ATN-224 treatment (Fig. 2 A–C). Consistent with this hypothesis, a number of unidentified redox regulated proteins, some of which could be PTPs, were also protected from oxidation during GF stimulation by SOD1 inhibition (Fig. 4A). Other possible PTPs that are affected by SOD1 inhibition must still be identified.

As we have shown in Fig. 3E, the levels of oxidized and inactive Prx increased upon ATN-224-mediated SOD1 inhibition potentially due to the excess superoxide generated. This result raises the possibility that the reversible inactivation of Prx that occurs during GF signaling (25, 31), allowing the accumulation of sufficiently high H2O2 concentrations, may be initiated by superoxide. SOD1 inhibition increased the steady-state levels of superoxide considerably as determined by direct measurements of superoxide, using the superoxide sensitive fluorescent dye DHE and other methods. Superoxide is short lived and reactive but did not spontaneously convert into H2O2 to any appreciable level, as previously discussed. Instead, the excess superoxide was involved in other reactions, such as with Prx and aconitase. The increase in the level of superoxide that occurs after a 50% inhibition in the activity of SOD1 inactivates ≈15–30% of total aconitase (32). At 500 nM ATN-224, a ≈50% inhibition of cytosolic aconitase activity in A431 cells was observed (Fig. 3B), suggesting that significantly high levels of superoxide are generated at those concentrations of ATN-224. Besides aconitase and Prx, our results show that superoxide reacted with a number of unidentified proteins, determined by measuring total protein carbonylation in ATN-224-treated A431 cells. Thus, these reactions account at least partially for the excess superoxide. Surprisingly, superoxide cannot oxidize PTP1B in vivo, but it does so in vitro with high efficiency (39). This suggests that either competing reactions scavenge superoxide very efficiently or that some type of compartmentalization prevents superoxide from reaching PTP1B, or both.

The data presented here indicate that SOD1 is essential for GF-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. It is unclear although how this inhibition contributes to the antiproliferative activity of ATN-224, because partial SOD1 inhibition with siRNA did not have an effect on proliferation but was sufficient to inhibit pERK upon EGF stimulation in A431 cells. It is reasonable to hypothesize that SOD1 inhibition will also affect other signaling pathways that are regulated by H2O2. Finally, the data presented here support the hypothesis that SOD1 is a therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer and that inhibiting SOD1 results in the down-regulation of multiple signaling pathways important for endothelial and tumor cell function.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Antibodies.

A431, HT-29, A549, and U87 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and HUVEC and HDFa were from Cascade Biologics. FGF-2, EGF, IGF-1 and PDGF were from R&D Systems. ATN-224 (choline tetrathiomolybdate) was manufactured under cGMP, using a proprietary manufacturing process. The antibodies against ERK1/2, pERK1/2, EGF, pEGF (Tyr 845, 992, 1045, 1068, 1148, and 1173), IGF-1Rβ, pIGF-1Rβ (Tyr 1135/1136), cleaved PARP, and PTEN were from Cell Signaling. Antibodies against pEGFR (Tyr 1086), Prx I, PrxII, Prx-2Cys, and Prx-SO3 were from Abcam. The antibody against PDGFRβ was from Upstate Biotechnology. The antibody against β-tubulin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and the antibody against SOD1 was from Biodesign International.

SOD Activity and MTT Assay.

SOD activity and MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assays were performed as described in ref. 1.

Western Blot Analysis and Immunoprecipitations.

Cells were plated in full growth media containing 10% FBS and incubated in ATN-224. Cells were then stimulated with the proper growth factor in the presence of 0.5% FBS media, harvested, and lysed in RIPA [1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4)] with protease inhibitors (Roche), 1 mM AEBSF (Calbiochem), and phosphatase inhibitors Set I and II (Calbiochem). Lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis, using an antibody specific with appropriate loading controls. Bands were quantitated using a Kodak Image Station 400. Immunoprecipitations were carried out by using 200–500 μg of cell extract incubated overnight with 20 μl of a protein G–agarose slurry (Roche) or streptavidin–agarose (Pierce).

SOD siRNA Transfection Experiments.

SOD1 Stealth siRNA (Invitrogen) or medium GC% Negative control siRNA (Invitrogen; catalog no. 12935-300) was diluted with OptiMEM I (Invitrogen). Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) was diluted 1:100 with siRNA and incubated for 0.5 h at ambient temperature. A431 cells were plated at 100,000 cells per well in a 12-well plate containing siRNA/RNAiMAX solution. After overnight incubation, the media was replaced with 10% FBS DMEM ± 7 μM ATN-224 and incubated for another 48 h. Cells were stimulated with 0.5% FBS and DMEM ± 100 ng/ml EGF for 10 min. Extracts were prepared with RIPA, 1 mM AEBSF, and phosphatase inhibitors Set I and II (Calbiochem).

Aconitase assay.

Aconitase was assayed according to the manufacturer's protocol (OXIS International), using a 96-well assay plate in a SpectraMax plate reader.

Detection of Superoxide or H2O2.

A431 cells were incubated with the indicated amounts of ATN-224 for 48 h. Cells were then trypsinized, washed with PBS, counted, and resuspended in PBS. For superoxide measurements, dihydroethidium (DHE) (Invitrogen) was added to the cells at 1.6 μM for 15 min. For H2O2 measurements, H2DCFDA (Invitrogen) at 20 μM was added to the cells for 15 min. After incubation with the respective dyes, the cells were extensively washed and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Determination of Redox Status of PTP.

To determine the redox status of PTEN, A431 cells that had been treated with ATN-224 for 48 h were exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 for 10 min, lysed in the presence of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), and analyzed by western blot with an antibody against PTEN. To determine the redox status of PTP1B, A431 cells were treated for 48 h with ATN-224 and lysed after treatment with EGF. The lysis buffer was degassed, supplemented with freshly prepared iodoacetic acid (10 mM), catalase (100 μg/ml), and superoxide dismutase (100 μg/ml) and placed on ice. Cell plates were moved into an anaerobic chamber and rapidly lysed. Alkylation of free thiols was allowed to occur for a 1 h. Cell lysate was then applied to desalting columns (Pierce) containing 1 mM DTT to allow reversibly oxidized PTPs to be reduced back. Samples were centrifuged, and the eluate was incubated with a biotin-conjugated PEO-iodoacetyl probe (5 mM) (Pierce) for 1 h. Biotinylated proteins were purified by streptavidin–Sepharose pulldown, and Western blot analysis was carried out by probing with a PTP1B antibody or streptavidin–HRP.

Statistical Analysis.

GraphPad software was used for all statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed by using unpaired, two-tailed t tests when comparing two variables.

Supporting Information.

Apoptosis studies, protein carbonylation, and the determination of redox status of PTP1B are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0709451105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Juarez JC, et al. Copper binding by tetrathiomolybdate attenuates angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation through the inhibition of superoxide dismutase 1. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4974–4982. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doñate F, et al. Identification of biomarkers for the anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor activity of the Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1) inhibitor Tetrathiomolybdate (ATN-224) Br J Cancer. 2008;98:776–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassouneh B, et al. Tetrathiomolybdate promotes tumor necrosis and prevents distant metastases by suppressing angiogenesis in head and neck cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1039–1045. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Q, Bao LW, Kleer CG, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Antiangiogenic tetrathiomolybdate enhances the efficacy of doxorubicin against breast carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan Q, Bao LW, Merajver SD. Tetrathiomolybdate inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis through suppression of the NFkappaB signaling cascade. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:701–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Q, et al. Copper deficiency induced by tetrathiomolybdate suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4854–4859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman VL, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Control of copper status for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:543–549. doi: 10.2174/156800905774574066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowndes SA, Harris AL. Copper chelation as an antiangiogenic therapy. Oncol Res. 2004;14:529–539. doi: 10.3727/0965040042707952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redman BG, et al. Phase II trial of tetrathiomolybdate in patients with advanced kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1666–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer GJ, et al. Treatment of metastatic cancer with tetrathiomolybdate, an anticopper, antiangiogenic agent: Phase I study. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;6:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowndes SA, et al. Phase I Study of ATN-224 (Choline Tetrathiomolybdate) in Metastatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imlay JA, Fridovich I. Assay of metabolic superoxide production in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6957–6965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fridovich I. The biology of oxygen radicals. Science. 1978;201:875–880. doi: 10.1126/science.210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reaume AG, et al. Motor neurons in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient mice develop normally but exhibit enhanced cell death after axonal injury. Nat Genet. 1996;13:43–47. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho YS, et al. Reduced fertility in female mice lacking copper-zinc superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7765–7769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elchuri S, et al. CuZnSOD deficiency leads to persistent and widespread oxidative damage and hepatocarcinogenesis later in life. Oncogene. 2005;24:367–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busuttil RA, et al. Organ-specific increase in mutation accumulation and apoptosis rate in CuZn-superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11271–11275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sentman ML, et al. Phenotypes of mice lacking extracellular superoxide dismutase and copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6904–6909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blander G, de Oliveira RM, Conboy CM, Haigis M, Guarente L. Superoxide dismutase 1 knock-down induces senescence in human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38966–38969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee SG. Cell signaling: H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonks NK. Redox redux: Revisiting PTPs and the control of cell signaling. Cell. 2005;121:667–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: From genes, to function, to disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:833–846. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee SG, et al. Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ushio-Fukai M. Redox signaling in angiogenesis: Role of NADPH oxidase. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SR, Kwon KS, Kim SR, Rhee SG. Reversible inactivation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in A431 cells stimulated with epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15366–15372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zwick E, Hackel PO, Prenzel N, Ullrich A. The EGF receptor as central transducer of heterologous signalling systems. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato K, Nagao T, Iwasaki T, Nishihira Y, Fukami Y. Src-dependent phosphorylation of the EGF receptor Tyr-845 mediates Stat-p21waf1 pathway in A431 cells. Genes Cells. 2003;8:995–1003. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2003.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T. Requirement for generation of H2O2 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi MH, et al. Regulation of PDGF signalling and vascular remodelling by peroxiredoxin II. Nature. 2005;435:347–353. doi: 10.1038/nature03587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner PR, Fridovich I. Inactivation-reactivation of aconitase in Escherichia coli: A sensitive measure of superoxide radical. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8757–8763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarpey MM, Wink DA, Grisham MB. Methods for detection of reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen: In vitro and in vivo considerations. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R431–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00361.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wardman P. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for measurement of oxidative and nitrosative species in cells and tissues: Progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:995–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SR, et al. Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20336–20342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo DW, et al. TIMP-2 mediated inhibition of angiogenesis: An MMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 2003;114:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00551-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhutani M, et al. Capsaicin is a novel blocker of constitutive and interleukin-6-inducible STAT3 activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3024–3032. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiesmann C, et al. Allosteric inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nsmb803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett WC, et al. Roles of superoxide radical anion in signal transduction mediated by reversible regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34543–34546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.