Abstract

The protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 is a positive regulator of growth factor signaling. Gain-of-function mutations in several types of leukemia define Shp2 as a bona fide oncogene. We performed a high-throughput in silico screen for small-molecular-weight compounds that bind the catalytic site of Shp2. We have identified the phenylhydrazonopyrazolone sulfonate PHPS1 as a potent and cell-permeable inhibitor, which is specific for Shp2 over the closely related tyrosine phosphatases Shp1 and PTP1B. PHPS1 inhibits Shp2-dependent cellular events such as hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF)-induced epithelial cell scattering and branching morphogenesis. PHPS1 also blocks Shp2-dependent downstream signaling, namely HGF/SF-induced sustained phosphorylation of the Erk1/2 MAP kinases and dephosphorylation of paxillin. Furthermore, PHPS1 efficiently inhibits activation of Erk1/2 by the leukemia-associated Shp2 mutant, Shp2-E76K, and blocks the anchorage-independent growth of a variety of human tumor cell lines. The PHPS compound class is therefore suitable for further development of therapeutics for the treatment of Shp2-dependent diseases.

Keywords: chemical biology, growth factor signaling, phosphatase inhibition, virtual drug screening

The protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) Shp2 (PTPN11) is mutated in human disease. Activating mutations cause Noonan syndrome (1) and have been identified in human cancer (2, 3). The autosomal human disorder Noonan syndrome is characterized by short stature, facial anomalies, heart disease, and increased risk of hematological malignancies. Distinct somatic gain-of-function mutations in PTPN11/SHP2 have been identified in >30% of the most common pediatric leukemia, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), and in myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, and some solid tumors (2, 4). The presence of activated or up-regulated Shp2 protein (5) in human cancers and other disease makes Shp2 an excellent target for generating interfering substances (6).

Shp2 is a nonreceptor PTP that harbors a classical tyrosine phosphatase domain and two N-terminal Src homology 2 (SH2) domains (7, 8). In its inactive state, the N-terminal SH2 domain blocks the PTP domain (9). This autoinhibition is relieved by binding of the SH2 domains to specific phosphotyrosine sites on receptors or receptor-associated adaptor proteins (10). Shp2 acts downstream of many receptor tyrosine kinases such as Met, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and insulin receptors (10). Genetic experiments in Drosophila (11) and Caenorhabditis elegans (12) and biochemical experiments in vertebrates (10) have shown that Shp2 acts upstream of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway to promote its activation. Several direct targets of Shp2 have been identified, including the platelet-derived growth factor receptors [PDGFR (13)/Torso (14)], the multiadaptor protein Gab1 (15), Csk-binding protein [Cbp/PAG (16)], and paxillin (17). Downstream of the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) receptor Met, Shp2 is activated by association with Gab1 and is both essential and sufficient for Met function (18, 19). Signaling through Met and its ligand, HGF/SF, has been implicated in high frequency in human cancer. Dysregulated Met signaling, through mutation or up-regulation of Met, has been associated with tumor progression, metastasis, and poor prognosis of survival (20). Inhibitors of Shp2 may thus be useful for the treatment of these human cancers and in limiting metastasis.

The identification of specific small-molecular-weight inhibitors of tyrosine phosphatases is a challenging endeavor, because the base of the catalytic cleft, the signature motif, is highly conserved among all PTPs. Most advanced are inhibitors of the tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B, a drug target in diabetes type II (21), whose PTP domain is closely related to Shp2 (22). Various protein phosphatase inhibitor classes have been identified by biology-oriented synthesis (23). Structural information of the protein/inhibitor complexes was helpful for the development of these inhibitors and revealed that small sequence differences in the periphery of the catalytic cleft determined specificity of these inhibitors (24, 25). A crystal structure of Shp2 is available only for the SH2-autoinhibited conformation (9). We have here modeled the PTP domain of Shp2 to reflect an induced-fit state for binding small-molecular-weight substrates. Using a high-throughput in silico screening procedure, we have identified the phenylhydrazonopyrazolone sulfonate, PHPS1, as a cell-permeable compound, which is highly specific for Shp2 over the closely related tyrosine phosphatases Shp1 and PTP1B. We have analyzed the structural determinants of this interaction and demonstrated that PHPS1 inhibits Shp2-dependent cellular functions and the growth of various human tumor cell lines. This compound is suitable for further development of therapeutics for the treatment of Shp2-dependent cancers and other diseases.

Results

Identification of the PHPS Compound Class of Shp2 Inhibitors.

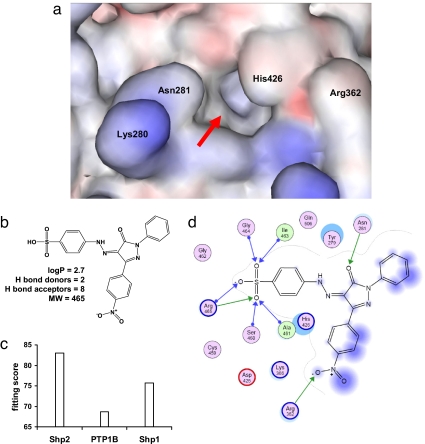

To identify active site-directed inhibitors of Shp2, we have homology modeled (26) the PTP domain of Shp2 based on sequence similarity to PTP1B, which exhibits 34% identity and 47% similarity to Shp2 (22). The x-ray structure of PTP1B bound to an effective competitive inhibitor [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1N6W (27)] was used as a template. In the resulting model of Shp2, the active center appears as a deep and narrow substrate-binding pocket (Fig. 1a, indicated by arrow).

Fig. 1.

PHPS1 is as an active site-directed small molecule inhibitor of Shp2. (a) Homology model of the active site of Shp2 as generated by WHAT_IF and visualized by Accelrys Viewer Lite v5.0. Selectivity-determining amino acid residues in the periphery of the active center are indicated by three-letter code; negatively charged areas are colored in red, and positively charged are in blue. Red arrow, active center. (b) Chemical structure and drug-like parameters (31) of PHPS1. (c) Fitting score values for PHPS1 in the active sites of Shp2, PTP1B, and Shp1, as generated by GOLD v2.1. (d) Ligand-interaction diagram of PHPS1 in the active site of Shp2, as generated by MOE v2006.3, modified. Blue arrows, backbone donor H bonds (Ser-460, Ala-461, Ile-463, Gly-464, Arg-465); green arrows, sidechain donor H bonds (Asn-281, Arg-362, Arg-465); purple circles, polar residues; purple/red circles, acidic residues; purple/blue circles, basic residues; light green circles, hydrophobic residues; blue spheres, ligand exposure; cyan spheres, receptor exposure.

Two-dimensional libraries of ≈2.7 million small-molecular-weight compounds from various sources were collected and transformed into a three-dimensional MOE (Chemical Computing Group) database of energy-minimized structures. In silico docking of these molecules into the modeled active center of Shp2 identified 2,271 hits (28). From these hits, 843 compounds were regarded as potent and 235 as specific (see Materials and Methods for the selection criteria used). We then examined 60 compounds that fulfilled these criteria in an enzymatic assay using the recombinantly expressed PTP domain of Shp2. Twenty of the tested compounds inhibited the Shp2-catalyzed hydrolysis of para-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) (29) by >50% when used at a concentration of 50 μM. Eight of the 20 compounds blocked HGF/SF-induced scattering of Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, which depends on Shp2 (30) (see below). The compound phenylhydrazonopyrazolone sulfonate 1 (PHPS1, Fig. 1b) inhibited Shp2 phosphatase activity and scattering of MDCK cells most effectively (see below). PHPS1 is a potential phosphotyrosine mimetic because of its sulfonic acid group. Good drug-like properties and membrane permeability (logP <5, H bond donors <5, H bond acceptors <10, molecular weight <500) (31) can be predicted for PHPS1. A four-step procedure for the synthesis of PHPS compounds was developed based on the C-acylation of triphenylphosphoranylidene acetate (32) [see supporting information (SI) Text, Materials and Methods, and Scheme S1] and used to vary its chemical structure for structure–activity studies and further lead optimization. Therefore, we focused on the PHPS compound class throughout this study.

PHPS1 Is an Active Site-Directed Inhibitor of Shp2.

Computer docking (28) predicts that PHPS1 interacts with the active site of homology-modeled Shp2 more strongly than with the corresponding sites of the closely related PTPs, Shp1 and PTP1B (Fig. 1c). As shown in a two-dimensional ligand docking diagram (Fig. 1d), the sulfonate moiety of PHPS1 potentially forms a lattice of seven hydrogen bonds with the PTP signature loop of Shp2 (Cys-459 to Arg-465), an aromatic π-stacking of the sulfonate attached phenyl ring with the aromatic side chains of Tyr-279 and His-426 and, most importantly, hydrogen bonds with Asn-281 and Arg-362 at the periphery of the catalytic cleft. The latter residues have been shown to be critical for specific inhibitor binding of the closely related tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B (33–35). To corroborate this hypothetical binding model, we determined the type of inhibition of Shp2 by PHPS1. Substrate titration studies using recombinant Shp2 (Fig. S1a) revealed that increasing concentrations of PHPS1 resulted in an increase in Km, with little or no effect on Vmax (Fig. S1 b and c). These findings indicate that inhibition of Shp2 by PHPS1 follows the Michaelis–Menten equation for a competitive inhibitor and suggest that PHPS1 binds the active center of Shp2.

Structure–Activity Relationship for the PHPS Compound Class.

To investigate the structural determinants of PHPS compounds for inhibition of Shp2, we performed enzymatic assays with Shp2 and scattering assays with MDCK epithelial cells using a variety of PHPS1 derivatives (see Material and Methods). Substitution of the sulfonic acid moiety of PHPS1 to sulfonamide (2) or carboxylate (3) resulted in a 2- and 10-fold lower inhibitory activity in the Shp2 enzyme assay, respectively, and complete loss of inhibition of HGF/SF-induced scattering (Table S1). Similar effects were seen when the nitro group of PHPS1 was shifted (4), omitted (5), or substituted by halogens (6, 7). Substitutions of the aromatic rings that are directly attached to the central pyrazolone unit of PHPS1 with nonaromatic moieties (8, 9) abolished inhibitory activity in both assays. In contrast, the attachment of a carboxylic ester group (10) onto PHPS1 resulted in a three-fold improved potency of inhibition of Shp2. This compound, however, did not exhibit higher potency in inhibition of HGF/SF-induced scattering.

Specificity Profiles of PHPS Compounds.

We profiled the most potent inhibitors, PHPS1 and PHPS4, against a panel of 11 recombinantly expressed PTPs, namely 10 PTPs of human (including the closely related Shp1 and PTP1B) and one of Mycobacterium tuberculosis origin (MptpA). Three PTPs, ECPTP, PTP1B, and Shp1, were more weakly inhibited by PHPS1 by factors of 2.5, 8, and 15, respectively (Table S2), whereas six PTPs were not inhibited even at the highest concentrations used in the assay (50 μM). The negative control, PHPS2, did not inhibit any PTP. PHPS4 was the most potent inhibitor of Shp2 and showed a specificity profile similar to PHPS1. We also determined the dissociation constants (Ki) of the enzyme/inhibitor complexes by substrate titration and applying Michaelis–Menten kinetics. The Ki value of PHPS1 for inhibition of Shp2 was 0.73 (±0.34) μM, which is in agreement with the value, 0.7 μM, calculated by the Cheng–Prussof equation (36) (see SI Text, Materials and Methods). The Ki values of PHPS1 for inhibition of PTP1B and Shp1 were found to be 8- and 15-fold higher, respectively (Table S3; see also inhibition by orthovanadate, suramin, and NSC-87877 in SI Text, Results). These findings show that PHPS1 is a selective inhibitor of Shp2, because it can distinguish between Shp2 and the most closely related PTPs, PTP1B, and Shp1.

The Shp2/PHPS1-binding model (Fig. 1d) suggests that the phenyl sulfonate group of PHPS1 acts as a phosphotyrosine mimetic and penetrates into the substrate-binding pocket of Shp2, whereas the pyrazolon core of PHPS1 and its substituents R1 and R2 (see Table S1) make contacts to residues at the periphery of this cleft. The amino acid residues Lys-280, Asn 281, Arg-362, and His-426 of Shp2 (see also Fig. 1a) are the only residues of this cleft that are not conserved between Shp2 and PTP1B. Our binding model predicts that these residues are of particular importance for inhibitor specificity, because they are all involved in binding to PHPS1. To confirm this, we generated a quadruple mutant of PTP1B (termed PTP1B-Q), where the respective residues in PTP1B were changed to the Shp2 counterparts (R47K, D48N, K116R, F182H). Indeed, this quadruple mutant of PTP1B showed a strongly increased affinity for PHPS1, now in the range of Shp2 (Table S3). Arg-362 is the only one of these four amino acids, which is not conserved between Shp2 and Shp1. We generated a mutant of Shp2, in which this arginine was changed to the lysine found in Shp1 (and PTP1B). Indeed, Shp2-R362K showed a strongly decreased affinity for PHPS1 (Table S3). These findings confirm the importance of these neighboring residues in binding to PHPS1 and indicate that binding of PHPS1 to other PTPs, which contain alternative residues at these positions, is suboptimal. Therefore, these findings help to explain the specificity of PHPS1 for Shp2.

PHPS1 Inhibits HGF/SF-Induced Scattering and Branching Morphogenesis.

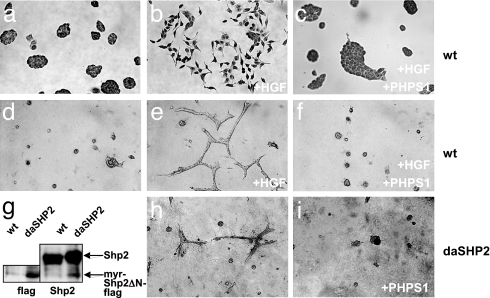

Induction of scattering (37, 38) and branching morphogenesis (39) of MDCK epithelial cells by the growth factor HGF/SF have been shown to depend on Shp2 (18, 30). Stimulation of MDCK epithelial cells grown on cell culture dishes with HGF/SF results in loss of cell–cell contacts, increased cell motility, and conversion from an epithelial to a fibroblast-like appearance (Fig. 2 a and b). We found that treatment of the cells with 5 μM PHPS1 completely inhibited HGF/SF-induced scattering (Fig. 2c, Table S1). Down-regulation of endogenous Shp2 by using small interfering ribonucleic acids [siRNAs (40)], which specifically target SHP2 mRNA, had a similar inhibitory effect as PHPS1 (Fig. S2 a–e).

Fig. 2.

PHPS1 inhibits HGF/SF-induced scattering and branching morphogenesis of MDCK epithelial cells. (a–c) MDCK cells were cultivated without stimulation (a) or stimulated with 1 unit/ml HGF/SF (b) or with 1 unit/ml HGF/SF and treated with 5 μM PHPS1 for 20 h (c). (d–f) MDCK cells were cultivated in a collagen gel without stimulation (d) or stimulated with 1 unit/ml HGF/SF (e) or with 1 unit/ml HGF/SF and treated with 10 μM PHPS1 (f). (g) Total cell lysates of wild-type or daSHP2 MDCK cells (stably expressing the dominant-active myr-SHP2ΔN-flag fusion protein) were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for flag epitope or Shp2, respectively. (h and i) daSHP2 MDCK cells were cultivated in a collagen gel and either untreated (h) or treated with 20 μM PHPS1 (i).

In three-dimensional collagen gels, MDCK cells form cyst-like colonies, which after treatment with HGF/SF extend and branch to form tubule-like structures (Fig. 2 d and e). This process mimics epithelial tubulogenesis that occurs, e.g., during the formation of the mammary gland, lung, liver, and kidney (41). We found that HGF/SF-induced branching morphogenesis could be completely inhibited by treatment of MDCK cells with PHPS1 (Fig. 2f). Although Shp2 has been shown to be required for HGF/SF-induced branching morphogenesis, it was not known whether it was sufficient. Therefore, we generated stable MDCK cell lines that expressed a dominant-active mutant of Shp2 (daShp2), where the inhibitory N-terminal SH2 domain has been replaced by a membrane targeting myristoylation signal (Fig. 2g). This fusion protein was shown to constitutively induce MAP kinase activation without extracellular ligand stimulation (42). We found that daSHP2-transfected MDCK cells were capable of forming tubular structures in collagen gels in the absence of HGF/SF (Fig. 2h). This finding demonstrates that activation of Shp2 is not only necessary but also sufficient for the induction of branched epithelial tubules. Remarkably, we found that this HGF/SF-independent process could be completely inhibited by treatment of the transfected cells with PHPS1 (Fig. 2i). This indicates that PHPS1 acts intracellularly to inhibit Shp2 phosphatase activity.

PHPS1 Specifically Inhibits Shp2-Dependent Signaling.

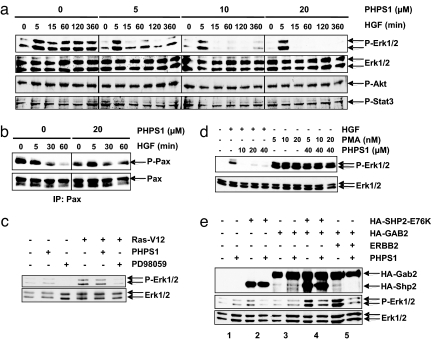

To investigate the biochemical mechanism by which PHPS1 exerts its intracellular inhibitory activity, we analyzed the effects of PHPS1 on Shp2 downstream signaling. First, we analyzed the ability of PHPS1 to block the activation of the Erk1/2 MAP kinase pathway downstream of HGF/SF (18, 19). PHPS1 inhibited HGF/SF-induced phosphorylation and thus activation of Erk1/2 in a dose-dependent manner over a time period of 15 min to 6 h (Fig. 3a). In contrast, transient phosphorylation of Erk1/2 after 5 min was not affected by PHPS1. PHPS1 exhibited no effect on HGF/SF-induced activation of PI3K/Akt (43, 44) or Stat3 (45) (Fig. 3a). Together, these findings indicate that PHPS1 mainly acts through interference with the sustained Shp2-dependent Ras/MAP kinase pathway. The focal adhesion component paxillin has recently been shown in EGF-stimulated mammary gland carcinoma cells and in a reconstituted system using purified components to be a direct target of Shp2 phosphatase activity (17). We found that HGF/SF induces dephosphorylation of paxillin in MDCK cells, and that PHPS1 significantly inhibited this dephosphorylation, in particular at later time points (Fig. 3b). This finding suggests that PHPS1 inhibits phosphatase activity of wild-type Shp2 directly.

Fig. 3.

PHPS1 inhibits Shp2-dependent signaling pathways. (a) PHPS1 inhibits Erk1/2 but not Akt and Stat3 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner. MDCK cells were pretreated with PHPS1 and stimulated with 1 unit/ml of HGF/SF. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phospho-Erk1/2 (P-Erk1/2), Erk1/2, phospho-Akt (P-Akt), or phospho-Stat3 (P-Stat3), respectively. (b) PHPS1 inhibits HGF/SF-induced paxillin dephosphorylation. MDCK cells were either untreated or treated with 20 μM PHPS1 and stimulated with 1 unit/ml of HGF/SF. Paxillin was immunoprecipitated from total cell lysates and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for paxillin and for phosphotyrosine. (c) PHPS1 does not inhibit Ras-V12-induced MAP kinase activation. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with an expression vector for RasV12 and either untreated or treated with 10 μM PHPS1 or PD98059 for 2 days, respectively. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phospho-Erk1/2 (P-Erk1/2) and Erk1/2. (d) PHPS1 does not inhibit PMA-induced MAP kinase activation. HEK293 cells were pretreated with serial dilutions of PHPS1 and stimulated with 1 unit/ml of HGF/SF or PMA, as indicated. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phospho-Erk1/2 (P-Erk1/2) or Erk1/2. (e) PHPS1 inhibits Shp2-dependent signaling. HEK293 cells were transfected with expression vectors for HA-GAB2, HA-SHP2-E76K, or ERBB2 and either untreated or treated with 20 μM PHPS1. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for hemagglutinin epitope (HA), phospho-Erk1/2 (P-Erk1/2), and Erk1/2.

To exclude that PHPS1 inhibits signaling downstream of Ras, we analyzed the effects of PHPS1 on the activation of MAP kinases by a constitutively active H-Ras mutant, Ras-V12 (46). PHPS1 did not inhibit Erk1/2 phosphorylation evoked by transfection of mouse fibroblasts with Ras-V12 (Fig. 3c). As a positive control, the synthetic inhibitor PD98059, which acts downstream of Ras on the MAP kinase kinase MEK (47), did inhibit when used at the same concentration. This finding indicates that PHPS1 interferes with Ras/MAP kinase signaling upstream of Ras and corroborates that Shp2 functions upstream or parallel of Ras (10, 41). To further exclude that PHPS1 is a general inhibitor of the MAP kinase pathway, we analyzed the effects of PHPS1 on the activation of this pathway after stimulation of human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). This activation has been shown to be independent of Shp2 (48) and instead depends on activation of protein kinase C and Raf (49) in a Ras-independent manner (50). We found that PHPS1 did not inhibit PMA-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation even at the highest dose used in the assay. As a positive control, PHPS1 inhibited HGF/SF-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation already at the lowest dose (Fig. 3d). This finding demonstrates that PHPS1 does not affect Shp2-independent MAP kinase activation. Furthermore, PHPS1 does not inhibit Met kinase activity directly (SI Text, Results, Fig. S3b).

Gain-of-function mutations in PTPN11, such as E76K, have been found to be associated with JMML (2). Shp2-E76K was shown to induce myeloid transformation, which depended on the PTPase activity of Shp2 and the presence of the multiadaptor protein Gab2 (51). Moreover, Gab2 has been shown to cooperate with the receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB2 in the Shp2-dependent activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and to promote the invasion of mammary epithelial cells (52). In a reconstituted system, transfection of HEK293 cells with SHP2-E76K resulted in increased phosphorylation of Erk1/2 by >10-fold, which was completely blocked by PHPS1 (Fig. 3e and Fig. S3a, lane 2). Cotransfection of SHP2-E76K with GAB2 resulted in hyperactivation of Erk1/2 by >40-fold, which could be inhibited by PHPS1 by 65% (Fig. 3e and Fig. S3a, lane 4). Remarkably, cotransfection of ERBB2 with GAB2 resulted in a 30-fold hyperactivation of Erk1/2, which could also be effectively inhibited by PHPS1 (Fig. 3e and Fig. S3a, lane 5). These findings indicate that PHPS1 can inhibit signaling downstream of transforming events such as mutational activation of Shp2, the up-regulation of the ErbB2 receptor and the action of the Gab2 adaptor.

PHPS1 Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Colony Formation of Human Tumor Cell Lines.

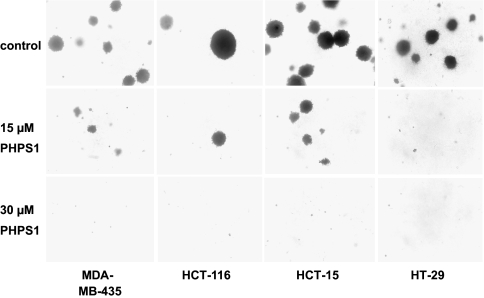

To determine whether PHPS1 can affect proliferation of cancer cells, a panel of human tumor cell lines (see Material and Methods) was treated with PHPS1 for 6 days, and cell number was measured by a standardized colorimetric assay (53). We found that treatment with 30 μM PHPS1 resulted in a reduction in cell number of between 0% (Caki-1) to 74% (HT-29) (Fig. S4a Upper). Analysis of Shp2 protein levels in these cell lines demonstrated that the unaffected cell line (Caki-1) expressed low levels, whereas the affected cell lines expressed high levels of Shp2 (Fig. S4a Lower). Interestingly, growth of the lung carcinoma cell line NCI-H661, which was shown to harbor a putative activating mutation in PTPN11 (4), was strongly inhibited by PHPS1 (59%). These findings indicate that PHPS1 inhibits the growth of tumor cells in a Shp2-dependent manner. We then examined the effect of PHPS1 on the colony-forming potential of human tumor cell lines by using a soft agar assay. Treatment of these cells with PHPS1 resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of colony formation in soft agar (Fig. 4, Fig. S4b). This finding demonstrates that PHPS1 effectively inhibits anchorage-independent growth of human tumor cells, which correlates strongly with their tumorigenicity and invasiveness (54). PHPS1 was also nontoxic and nonmutagenic (SI Text, Results; Fig. S4 c and d).

Fig. 4.

PHPS1 inhibits soft agar colony formation of human tumor cells. The indicated human cancer cell lines were grown in soft agar for 4 weeks and treated with solvent control or PHPS1 every 7 days. Representative pictures are shown (see Fig. S4b for quantification).

Discussion

The PTP Shp2 is an essential component downstream of receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases and has been shown to play an important role in the development of human cancers. We have here identified a phenylhydrazonopyrazolone sulfonate compound, PHPS1, that blocks the active site of Shp2 and inhibits its enzymatic activity in the low micromolar range but is less or not active against related PTPs. We show that PHPS1 inhibits Shp2-dependent cellular functions and the growth of a panel of human tumor cell lines. Furthermore, PHPS1 is drug-like and nontoxic, and improved versions of this compound may in the future be used not only for further dissection of the RTK/Ras pathways but also for inhibiting cancer progression.

PHPS1 is the first compound that specifically inhibits Shp2 over the closely related phosphatases Shp1 and PTP1B. We show here that inhibitor specificity depends on four critical amino acid residues (Lys-280, Asn-281, Arg-362, and His-426) found in the periphery of the catalytic cleft of Shp2. Lys-280 and His-426 are predicted to form van der Waals contacts with PHPS1, whereas Asn-281 and Arg-362 may form hydrogen bonds. The PTP1B residues Arg-47 and Asp-48, which occupy equivalent positions to Lys-280 and Asn-281 in Shp2, have been described as selectivity determining residues for binding inhibitors (24, 25). The guanidinium side chain of Arg-362 is predicted to form an essential hydrogen bond with the nitro group of PHPS1. An interaction between this PTP residue and a PTP inhibitor had not been described. Shp1 and PTP1B both possess a lysine at the equivalent position, and introduction of this residue into Shp2 by site-directed mutagenesis leads to a decreased affinity for PHPS1. This finding thus provides an explanation for the specificity of PHPS1 for Shp2 over these two related PTPs. PHPS1 inhibits ECPTP/PTPRR 2.5-fold weaker than Shp2 To clarify the basis for this activity, we modeled the PTP domain of ECPTP in an analogous manner to that of Shp2 and docked PHPS1 into its active site. We detected the formation of hydrogen bondings of the nitro group of PHPS1 not only with Lys-497 of ECPTP (which corresponds to Arg-362 of Shp2) but also with Asn-498, which is a glycine in many other PTPs at this position (data not shown). The GOLD fitting score value of PHPS1 for ECPTP lies between those for Shp2 and Shp1/PTP1B (data not shown). These findings corroborate the observed affinities of PHPS1 for the different PTPs.

PHPS1 inhibits not only the phosphatase activity of Shp2 in vitro but also its cellular activities, namely the induction of cell scattering and the formation of epithelial tubular structures by HGF/SF. Recruitment and activation of Shp2 downstream of the HGF/SF receptor Met has been shown to be a critical step for these biological events (18, 19). We demonstrate that activation of Shp2 is not only required but also sufficient for the induction of tubular morphogenesis, and that this event is inhibited by PHPS1. Because the constitutively active Shp2 used to induce tubulogenesis acts intracellularly, these data also demonstrate that the PHPS1 target is intracellular. The main signaling pathway regulated by Shp2 is the Ras/MAP kinase pathway (Fig. S5). We show that PHPS1 inhibits the Shp2-dependent activation of this pathway. Indeed, it inhibits only the sustained phase of activation of Erk1/2 that has been shown to depend on Shp2, but not the initial transient phase, which is Shp2-independent and mediated by recruitment of growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (Grb2) and the Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor Son of Sevenless (Sos) (55). Furthermore, PHPS1 has no effect on the Shp2-independent activation of Erk1/2 induced by PMA or oncogenic Ras or on the activation of other Shp2-independent events such as the PI3K/Akt pathway. Thus, PHPS1 is not a general signaling inhibitor of cytoplasmic signaling but instead acts specifically at the level of Shp2.

Shp2 is mutationally activated in human tumors, in particular in pediatric leukemias (2), and is up-regulated in adult leukemias (5). Moreover, Shp2 is essential for signaling by the receptor tyrosine kinase Met, which is itself found mutated or overexpressed in many different human cancers (20) and linked to metastasis (56). Shp2 also acts downstream of the RTKs ErbB2 (57) and Ret (58), both of which are also involved in cancer progression. We could show that PHPS1 inhibits the hyperactivation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway evoked by expression of the leukemic oncogene SHP2-E76K or the breast cancer oncogenes GAB2 and ERBB2/HER2, which has been shown to depend on Shp2 (52). PHPS1 also efficiently blocks proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of various human tumor cells, whereas it was not cytotoxic against normal epithelial cells. These properties are prerequisites before we can test this compound in animal tumor models.

In summary, we have identified a specific inhibitor of the PTP Shp2. This compound, PHPS1, is cell-permeable, noncytotoxic, and specific for Shp2-dependent signaling, whereas we observed no off-target effects against Shp2-independent signaling. This specificity, together with its activity toward tumor cell line growth, its simple chemical structure and excellent pharmacological properties, make this compound class suitable for further development of novel therapeutics for the treatment of Shp2-dependent human malignancies and other diseases. Moreover, the identified compound class will facilitate the further characterization of Shp2 substrates and dissection of Shp2-dependent signaling pathways.

Materials and Methods

Screening.

The PTP domains of Shp2 (amino acids 225–529) and Shp1 (amino acids 222–523) that contain the substrate-binding pockets were aligned with the PTP domain of PTP1B (amino acids 2–285) by using ClustalW (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston). Amino acids 239–246, 296–300, 314–321, and 413 of Shp2 (and the corresponding amino acids of Shp1) were omitted. A homology model of Shp2 was built in silico by using the modeling software WHAT_IF (G. Vriend, Center for Molecular and Biomolecular Informatics, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) (26). PTP1B bound to a difluoromethylenephosphonate containing compound that inhibits this phosphatase (PDB ID no. 1N6W) was used as a template. The orientations of the side chains of Arg-278, Lys-280, and Thr-466 of Shp2 were manually adjusted. A two-dimensional molecular database of 2.7 million commercially available small molecules was built in SDF format (MDL, Symyx). Counterions were removed, and chemical structures were transformed into three dimensions and energy-minimized by using a MFF89FF force field by Molecular Environment (MOE) v2003.2 (Chemical Computing Group, Toronto). A three-dimensional molecular database was built in MOE format and converted into SDF format without removing redundancies. The docking program GOLD v2.1 (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center) (28) on a personal computer with Intel Pentium IV central processing unit (2 GHz) was used for docking of the small molecules into the substrate-binding pocket (radius of 15 Å) of the Shp2 homology model under low stringent conditions (three dockings per molecule, 1,000 operations per docking). Hits were ranked according to their fitting scores (FS), and hits with fitting scores >60 were redocked against the homology models of Shp2 and Shp1 and the modeling template PTP1B under more stringent conditions (10 dockings per molecule, 30,000 operations per docking). Hits with fitting scores >80 were regarded as potent. Hits with differences in fitting scores according to the formula 2×FS(Shp2)−FS(Shp1)−FS(PTP1B) >20 were regarded as specific. Moreover, hits were analyzed for chemical similarity by SARNavigator v1.5 (Tripos). Multiple hits and hits that appeared in groups of chemical similarity were regarded as more significant. Compounds with unfavorable properties (e.g., containing amino or aldehyde groups) were excluded from further analysis. The residual compounds were analyzed visually for their formation of hydrogen bonds between a potential phosphate mimicking group and the signature loop of Shp2 (Cys-459 to Arg-465), the π-stacking of an aromatic residue between the aromatic side chains of Tyr-279 and His-426 and for hydrogen bonds with Lys-280, Asn-281 and/or Arg-362. Docked molecules were visualized by ViewerLite 5.0 (Accelrys). Ligand-interaction diagrams were generated by MOE v2006.3 (Chemical Computing Group).

Synthesis.

Compounds 4, 6, 7, and 10 were synthesized as described in SI Text, Materials and Methods. Compounds 1-3, 5, 8, and 9 were purchased from VitasMLab, Asinex, or Chembridge. Compounds were dissolved in DMSO and stored at −20°C.

Additional Methods.

Methods for recombinant proteins, enzymatic assays, cell assays, and assessment of cytotoxicity and mutagenicity are described in SI Text, Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank S. Knapp and A. Barr (Structural Genomics Consortium, University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K.) for providing the recombinant PTPs; C. Birchmeier and A. Garratt (Max Delbrück Center) for providing the plasmid pSV-neu; G. Krause (Leibniz Institute for Molecular Pharmacology) for help in protein modeling; F. Hinterleitner (Leibniz Institute for Molecular Pharmacology) for technical assistance; and J. Holland (Max Delbrück Center) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. A.U. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/data/0710468105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tartaglia M, et al. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:465–468. doi: 10.1038/ng772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tartaglia M, et al. Somatic mutations in PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:148–150. doi: 10.1038/ng1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohi MG, Neel BG. The role of Shp2 (PTPN11) in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentires-Alj M, et al. Activating mutations of the Noonan syndrome-associated SHP2/PTPN11 gene in human solid tumors and adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8816–8820. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu R, et al. Overexpression of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase is implicated in leukemogenesis in adult human leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:3142–3149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherr M, et al. Enhanced sensitivity to inhibition of SHP2, STAT5, and Gab2 expression in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) Blood. 2005;107:3279–3287. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman RM, Jr, Plutzky J, Neel BG. Identification of a human src homology 2-containing protein-tyrosine-phosphatase: A putative homolog of Drosophila corkscrew. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11239–11243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel W, Lammers R, Huang J, Ullrich A. Activation of a phosphotyrosine phosphatase by tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 1993;259:1611–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.7681217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hof P, Pluskey S, Dhe-Paganon S, Eck MJ, Shoelson SE. Crystal structure of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 Cell. 1998;92:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The 'Shp'ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst R, et al. Daughter of sevenless is a substrate of the phosphotyrosine phosphatase Corkscrew and functions during sevenless signaling. Cell. 1996;85:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutch MJ, Flint AJ, Keller J, Tonks NK, Hengartner MO. The Caenorhabditis elegans SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-2 participates in signal transduction during oogenesis and vulval development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:571–585. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klinghoffer RA, Kazlauskas A. Identification of a putative Syp substrate, the PDGF beta receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22208–22217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleghon V, et al. Opposing actions of CSW and RasGAP modulate the strength of Torso RTK signaling in the Drosophila terminal pathway. Mol Cell. 1998;2:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montagner A, et al. A novel role for Gab1 and SHP2 in epidermal growth factor-induced Ras activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5350–5360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SQ, et al. Shp2 regulates SRC family kinase activity and Ras/Erk activation by controlling Csk recruitment. Mol Cell. 2004;13:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren Y, Meng S, Mei L, Zhao ZJ, Jove R, Wu J. Roles of Gab1 and SHP2 in paxillin tyrosine dephosphorylation and Src activation in response to epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8497–8505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaeper U, et al. Coupling of Gab1 to c-Met, Grb2, and Shp2 mediates biological responses. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1419–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maroun CR, et al. The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 is required for sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and epithelial morphogenesis downstream from the met receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8513–8525. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8513-8525.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:915–925. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang S, Zhang ZY. PTP1B as drug target: Recent developments in PTP1B inhibitor discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen JN, et al. Structural and evolutionary relationships among protein tyrosine phosphatase domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7117–7136. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7117-7136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noren-Muller A, et al. Discovery of protein phosphatase inhibitor classes by biology-oriented synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10606–10611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601490103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iversen LF, et al. Structure-based design of a low molecular weight, non-phosphorus, nonpeptide, and highly selective inhibitor of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10300–10307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asante-Appiah E, et al. The YRD motif is a major determinant of substrate and inhibitor specificity in T-cell protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26036–26043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vriend G. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graphics. 1990;8 doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. 52–56-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun JP, et al. Crystal structure of PTP1B complexed with a potent and selective bidentate inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12406–12414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCain DF, Zhang ZY. Assays for protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 2002;345:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)45042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kodama A, et al. Involvement of an SHP-2-Rho small G protein pathway in hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-induced cell scattering. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2565–2575. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Dahshan A, Weik S, Rademann J. C-acylations of polymeric phosphoranylidene acetates for c-terminal variation of peptide carboxylic acids. Org Lett. 2007;9:949–952. doi: 10.1021/ol062754+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iversen LF, et al. Steric hindrance as a basis for structure-based design of selective inhibitors of protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14812–14820. doi: 10.1021/bi011389l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo XL, Shen K, Wang F, Lawrence DS, Zhang ZY. Probing the molecular basis for potent and selective protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41014–41022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murthy VS, Kulkarni VM. Molecular modeling of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP 1B) inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:897–906. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00342-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoker M, Gherardi E, Perryman M, Gray J. Scatter factor is a fibroblast-derived modulator of epithelial cell mobility. Nature. 1987;327:239–242. doi: 10.1038/327239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weidner KM, Behrens J, Vandekerckhove J, Birchmeier W. Scatter factor: Molecular characteristics and effect on the invasiveness of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2097–2108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.5.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montesano R, Schaller G, Orci L. Induction of epithelial tubular morphogenesis in vitro by fibroblast-derived soluble factors. Cell. 1991;66:697–711. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90115-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosario M, Birchmeier W. How to make tubes: Signaling by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cunnick JM, et al. Regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway by SHP2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9498–9504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Royal I, Park M. Hepatocyte growth factor-induced scatter of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27780–27787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khwaja A, Lehmann K, Marte BM, Downward J. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase induces scattering and tubulogenesis in epithelial cells through a novel pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18793–18801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boccaccio C, et al. Induction of epithelial tubules by growth factor HGF depends on the STAT pathway. Nature. 1998;391:285–288. doi: 10.1038/34657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joneson T, White MA, Wigler MH, Bar-Sagi D. Stimulation of membrane ruffling and MAP kinase activation by distinct effectors of RAS. Science. 1996;271:810–812. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamauchi K, Milarski KL, Saltiel AR, Pessin JE. Protein-tyrosine-phosphatase SHPTP2 is a required positive effector for insulin downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:664–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marquardt B, Frith D, Stabel S. Signalling from TPA to MAP kinase requires protein kinase C, raf and MEK: Reconstitution of the signalling pathway in vitro. Oncogene. 1994;9:3213–3218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ueda Y, et al. Protein kinase C activates the MEK-ERK pathway in a manner independent of Ras and dependent of Raf. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23512–23519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohi MG, et al. Prognostic, therapeutic, and mechanistic implications of a mouse model of leukemia evoked by Shp2 (PTPN11) mutations. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bentires-Alj M, et al. A role for the scaffolding adapter GAB2 in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2006;12:114–121. doi: 10.1038/nm1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for celluar growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freedman VH, Shin SI. Cellular tumorigenicity in nude mice: Correlation with cell growth in semi-solid medium. Cell. 1974;3:355–359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Egan SE, et al. Association of Sos Ras exhange protein with Grb2 is implicated in tyrosine kinase signal transduction and transformation. Nature. 1993;363:45–51. doi: 10.1038/363045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benvenuti S, Comoglio PM. The MET receptor tyrosine kinase in invasion and metastasis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:316–325. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deb TB, et al. A common requirement for the catalytic activity and both SH2 domains of SHP-2 in mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation by the ErbB family of receptors. A specific role for SHP-2 map, but not c-Jun amino-terminal kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16643–16646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jhiang SM. The RET proto-oncogene in human cancers. Oncogene. 2000;19:5590–5597. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.