Abstract

Background and purpose:

Evidence is accumulating to support a role for interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in astrocyte proliferation. However, the mechanism by which this cytokine modulates this process is not fully elucidated.

Experimental approach:

In this study we used human astrocytoma U-373MG cells to investigate the role of nitric oxide (NO), intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) in the signalling pathway mediating IL-1β-induced astrocyte proliferation.

Key results:

Low IL-1β concentrations induced dose-dependent ERK activation which paralleled upregulation of cell division, whereas higher concentrations gradually reversed both these responses by promoting apoptosis. Pretreatment with the nonspecific NOS inhibitor, N-ω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) or the selective iNOS inhibitor, N-[[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimidamide dihydrochloride (1400W), antagonized ERK activation and cell proliferation induced by IL-1β. Inhibition of cGMP formation by the guanylate cyclase inhibitor, 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), partially inhibited ERK activation and cell division. Functionally blocking Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum with ryanodine or 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB), inhibiting calmodulin (CaM) activity with N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride (W7) or MAPK kinase activity with 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthiol]butadiene (U0126) downregulated IL-1β-induced ERK activation as well as cell proliferation. The cytokine induced a transient and time-dependent increase in intracellular NO levels which preceded elevation in [Ca2+]i.

Conclusions and implications:

These data identified the NO/Ca2+/CaM/ERK signalling pathway as a novel mechanism mediating the mitogenic effect of IL-1β in human astrocytes. As astrocyte proliferation is a hallmark of reactive astrogliosis, our results reveal a new potential target for therapeutic intervention in neuroinflammatory disorders.

Keywords: interleukin-1β, astrocyte proliferation, calcium/calmodulin, nitric oxide, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase, neuroinflammation

Introduction

Astrocytes comprise the major glial cell population within the CNS, which is involved in multiple brain functions in physiological conditions, including neuronal development, synaptic activity and homeostatic control of the extracellular environment (Swanson et al., 2004; Darlington, 2005). They also actively participate in the processes triggered by brain injuries, aimed at limiting and repairing brain damage (Emily et al., 2004; Takuma et al., 2004). Indeed, after any degenerative injury or insult, astrocytes are activated in a process known as reactive astrogliosis (Eng et al., 1992; Suryadevara et al., 2003; Sriram et al., 2004). The function of reactive astrocytes is controversial, in that both beneficial and detrimental properties are postulated. In this context, although moderate activation of astrocytes may be crucial in the recovery of the injured CNS by secretion of neurotrophic factors, a rapid, severe and prolonged activity of these cells, as observed in chronic neurodegenerative diseases, is believed to augment or initiate a massive inflammatory response leading to neuronal death (Tani et al., 1996).

Reactive astrogliosis is generally characterized by cell proliferation, morphological changes, such as hypertrophy, emission of branches in existing astrocytes and increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (Takamiya et al., 1988; Narita et al., 2004). A combination of studies, performed in vivo and in vitro by several groups using different CNS injury models, has convincingly implicated a number of cytokines in the generation or modulation of these processes (John et al., 2003). Among these, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), which is known to be expressed, together with its receptors, in astrocytes, stands out as being the major neuroinflammatory cytokine responsible for astrogliosis (Woiciechowsky et al., 2004; Hailer et al., 2005). However, the specific signalling mechanism by which IL-1β regulates this process and in particular cell proliferation, is not yet fully elucidated.

Our recent findings showed that nitric oxide (NO) modulated cell division in astrocytoma cell via activation of Ca2+/calmodulin (CAM) and the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK1/2) (Meini et al., 2006). In another series of experiments, we showed that the same NO/Ca2+ cascade is part of the signalling pathway subserving the pyrogenic proinflammatory function of IL-1β (Meini et al., 2000; Palmi and Meini, 2002), raising the likelihood that this signalling mediates the cytokine-induced cell division. In the present study, we investigated the effect of IL-1β on astrocyte proliferation and the involvement of the NO/Ca2+ signalling in ERK activation and cell division. This in turn may shed light on the role of IL-1β on astrocyte-associated neuroinflammation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human astrocytoma U-373MG cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. According to the experimental sections, cell suspensions containing 1.25 × 105 or 1.5 × 103 viable cells ml−1 were used. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in 95% air/5% CO2 until about 80% confluence. After adherence (5–6 h), cells were placed in fresh serum-free medium for 12 h prior to each experiment.

Cell proliferation

Cells (1.5 × 103) resuspended in 10% serum were seeded in 96-multiwell plates. After adherence (5–6 h), the supernatant was replaced with serum-free medium to synchronize the cell cycle. After 12 h, cells were pretreated for 30 min with different inhibitors and then stimulated for 1 h with IL-1β. After this period, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium supplemented with 1% FCS for 24 and 48 h. Thereafter, cells were fixed in 100% methanol and stained with Diff-Quik (Mertz-Dade, Behring, Milan, Italy). Total cells per well were counted at × 100 magnification.

[3H]Thymidine incorporation assay

DNA synthesis during the S phase of the cell cycle was assessed in the experiments with N-ω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and N-[[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimidamide dihydrochloride (1400W) by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. Twelve hours after stimulation, cells (1.5 × 103) were labelled with 1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (7.8 Ci mmol−1) (PerkinElmer, Milan, Italy) for a period of 12 h. Thereafter, the medium was aspirated, cells were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 5% trichloroacetic acid for 20 min at 4 °C. Cell layers were lysed with 400 μl of 0.1 N NaOH/2% Na2CO3 (1:1), and the lysate was transferred to a vial containing 3 ml of scintillation fluid (OptiPhase HiSafe 3, PerkinElmer). The radioactive content of each vial was determined using a β-counter.

Determination of intracellular Ca2+ concentration

Cells (1.5 × 103) plated in 96-well microlitre plates (Costar, Badhoerdorp, The Netherlands) were incubated for 75 min in the dark with 10 μM Fura 2 acetoxy-methyl ester (Fura 2/AM) dissolved in HBS (in mM: NaCl, 140; KCl, 4; HEPES, 10 and glucose, 10) supplemented with 0.03% pluronic acid F-127. IL-1β at a final concentration of 1 ng ml−1 was added to the Fura 2/AM solution 0, 30, 45, 60 and 75 min after the beginning of the incubation. At the end of each stimulation period, cells were washed and Ca2+ fluorescence recorded at excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm using a Fluoroskan Ascent (Thermo Labsystems, Milan, Italy) fluorimeter. Quantitative intracellular Ca2+ values were obtained from the observed fluorescence ratio 340:380 (R) and fluorescence calibration following the procedure described by Tsien et al. (1982). In brief, to obtain the minimum fluorescence ratio (Rmin), 400 mM EGTA (pH 8.7) and 16 μM ionomycin were added sequentially, followed by 10 mM CaCl2 to obtain the maximum fluorescence ratio (Rmax) and 5 mM MnCl2 to measure the autofluorescence. After correction of R, Rmin and Rmax for autofluorescence, the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was determined by the equation:

where sf/sb is the ratio of fluorescence values measured before and after CaCl2 addition at a wavelength of 380 nm, and Kd is the dissociation constant of Fura 2 acetoxy-methyl ester for Ca2+.

Western blot analysis

Cells (1.25 × 105) were stimulated for 1 h with IL-1β and then treated with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris base, pH 7.4, 75 mM NaCl, 20 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 2.5 mM NaF, 2.5 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate and 1% Triton X-100), frozen at −80 °C for 24 h and defrosted on ice. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and protein concentration of the supernatant determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA Protein Assay Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples of 50–60 μg protein in 5 × loading buffer (65 mM Tris base, pH 7.4, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol and 1% bromophenol blue) were boiled for 5 min, loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels and separated by molecular size. The gels were then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Immunodetection of the protein of interest was performed by western blot analysis by using polyclonal rabbit phospho-specific ERK antibodies (phospho-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Thr202/Tyr204); 1:5000; Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany). Antibody binding to protein was detected using anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000; Santa Cruz) and visualized autoradiographically on film using enzyme-linked chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Milan, Italy). The blots were then stripped and reprobed with total (phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated) ERK1/2 protein (1:5000; Santa Cruz) to assess the total protein load.

Assessment of apoptotic cell death

Cells were grown on glass coverslips at a seeding density of 1.5x103 cells ml−1 and treated for 1 h with IL-1β. Then, cells were reincubated in culture medium supplemented with 1% FCS for 24 min and fixed for 25 min with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. After three washes in PBS at room temperature, paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were permeabilized by using 0.25% Triton X-100 and nonspecific binding sites were blocked by 30 min incubation with 5% BSA–PBS. The slides were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the active anti-caspase-3 primary antibody (1:100; Sigma, Milan, Italy). After several washes, cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h at room temperature (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich, Italy), rinsed in PBS, counterstained with the fluorescent nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:1000; Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) and washed three times with PBS. Distilled water was used for the final wash. The slides were mounted with antifading medium glycerol–PBS containing 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO; Sigma-Aldrich, Italy), and examined by the Zeiss Axioplan2 light microscope equipped with epifluorescence. Negative controls for the immunostaining experiments were performed by omitting primary antibody. Acquisition of images and merge of signal were obtained by axio Vision 3.1 software. The number of DAPI-positive (DAPI+) and caspase-3-positive (caspase-3+) cells were counted and expressed as caspase-3-immunoreactive astrocytes per square millimetre. The number of DAPI+ cells were counted for treated and control groups to determine total cell number. The percentage of DAPI+ and caspase-3+ cells was expressed relative to the DAPI+ cells and represented the mean±s.e.mean from three independent determinations.

Densitometric analysis

Densitometric analysis of the phospho-ERK signal before and after each treatment was determined by scanning immunoblots using a PDI 420e densitometric scanner and normalizing each scan to that of corresponding total ERK (Santa Cruz) signal in the same gel.

Determination of intracellular NO levels

NO released from cells was measured electrochemically by using an NO-specific electrode (inNO, Nitric Oxide measuring system and sensor; Innovative Instrument Inc., Queen Brooks Court, Tampa, FL, USA). The design of the electrode has been previously described in detail (He and Liu, 2001). In short, NO was allowed to diffuse through a semipermeable membrane followed by oxidation at a working platinum electrode resulting in the presence of a small electric current. The magnitude of the redox current is in direct proportion to the concentration of NO in the sample and is amplified by the NO meter and registered by a computer. The instrument has an inherently high selectivity due to the fact that the electrodes are separated from the sample in which measurements are being made by gas-permeable hydrophobic membranes. This rules out any interference from solution or dissolved species other than gas. The NO instrument was calibrated prior to daily experiment with the standard NO generated from the reaction of a solution of NaNO2 and a solution containing H2SO4, K2SO4 and KI. In our experiments, a cell suspension containing 1.5 × 103 cells ml−1 was seeded in 96-well microlitre plates for 24 h. After replacing culture medium with serum-free medium, the tip of the NO electrode was slowly moved vertically to the cell surface. Immediately afterwards, IL-1β was added to the well and current change was monitored for 75 min. The sensor under these conditions can detect NO concentrations between 0.1 nM and 10 μM.

Data analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, means±s.e.mean of triplicate determinations obtained in 3–5 separate experiments were compared statistically by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Barlett's test. Groups of cell proliferation, ERK activity, caspase immunoreactivity, DNA synthesis, [Ca2+]i and NO data were compared across all treatment conditions. For all experiments, P<0.05 was considered significant.

Materials

Fura 2 acetoxy-methyl ester in anhydrous dimethylsulphoxide (Calbiochem, Milan, Italy) was stored in aliquots at −80 °C and thawed prior to use. IL-1β was purchased from Peprotech EC (Milan, Italy). Pluronic acid F-127 (BASF Wyandotte, New Jersey, USA) was from Molecular Probes (Milan, Italy). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and 10% FCS were from Sigma (Italy). CaM inhibitors, N-(6-aminohexyl)-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride (W5), N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride (W7) and 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthiol]butadiene (U0126) were from Tocris Cookson Ltd (Bristol, UK). Human astrocytoma U-373MG cells were provided by courtesy of Professor Pessina (Department of Physiology, Siena University, Italy). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA).

Results

Time-course effect of different concentrations of IL-1β on cell proliferation, ERK1/2 activation and apoptosis in human astrocytoma cells

To gain further insight into the role of IL-1β on astrocyte proliferation, human astrocytoma U-373MG cells were stimulated with different (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 50 ng ml−1) concentrations of IL-1β for 1 h and then reincubated in IL-1β-free medium for 24 and 48 h. The results illustrated by in Figure 1a showed that treatment with 0.01, 0.1 and 1 ng ml−1 of IL-1β induced a dose-dependent upregulation of cell proliferation. Although this effect was negligible with the lowest dose, it became significant with the 0.1 and 1 ng ml−1 concentrations (P<0.001), and proliferation was markedly higher than the controls, by 24 h after stimulation. In contrast, levels of IL-1β above this threshold (10 and 50 ng ml−1 IL-1β) induced a progressive reduction of the proliferative response below the peak value. By 48 h after stimulation, the concentration-dependent profile of proliferation induced by IL-1β was similar to that observed at 24 h, even though the relative increases in proliferation were lower.

Figure 1.

Concentration dependence of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) regulation of cell proliferation, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation and apoptosis in human astrocytoma cells. (a) Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were stimulated with different doses of IL-1β for 1 h and then reincubated in IL-1β-free medium supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 24 and 48 h. Proliferation was assessed by cell counting. The data shown that represent percentage of control values (100%=untreated cells, at 0 h) are mean±s.e.mean from five independent determinations. (b) Apoptotic cells (24 h after treatment) were expressed as percentage of caspase-3 immunoreactive (caspase-3+) cells of total cells determined by DAPI staining. Bars are mean±s.e.mean from three independent determinations. (c) Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were stimulated with different doses of IL-1β for 1 h and then lysed. Lysed cells were analysed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blot by using anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2). Total ERK1/2 (tERK1/2) was used to verify equal loading of protein across lanes. Data are representative of five independent experiments. (d) Densitometric analysis of pERK bands was performed by normalizing them to their respective tERK1/2 and expressed as percentage of control (untreated cells). Bars are mean±s.e.mean from five independent determinations. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing each IL-1β concentration value with the corresponding time control by using one-way ANOVA followed by Barlett's test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

To determine whether apoptotic cell death contributed to the antiproliferative effect of the high IL-1β concentrations, we counted caspase-3+ cells following treatment with different IL-1β concentrations. The results in Figure 1b show that the apoptotic effects of 0.01, 0.1 and 1 ng ml−1 IL-1β were comparable to those of controls, whereas the effects of 10 and 50 ng ml−1 IL-1β were significantly higher (P<0.05 and 0.01, respectively) and correlated with their antiproliferative responses (see Figure 1a).

As it is well established that MAPK signalling controls many cell functions, including proliferation, we sought to investigate the effect of IL-1β on ERK expression. The results, reported in Figure 1c, showed that 1 h treatment with the lower concentrations (0.01, 0.1 and 1 ng ml−1) of IL-1β induced a progressive and dose-dependent activation of these proteins, with the maximum stimulation occurring at 1 ng ml−1. Above this threshold level, IL-1β decreased ERK phosphorylation, until control levels of phosphorylation were reached with the highest dose.

Taken together, these data indicated that effects of IL-1β on cell proliferation strictly paralleled that on ERK activation and suggested that phosphorylation of this kinase was part of the mechanism underlying the mitogenic effect of IL-1β.

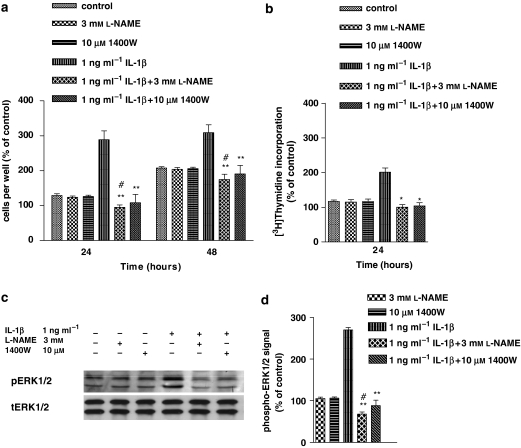

Effect of L-NAME and 1400W on IL-1β-induced cell proliferation DNA synthesis and ERK1/2 activation in human astrocytoma cells

To investigate whether NO was part of the intracellular signalling responsible for the mitogenic effect of IL-1β, L-NAME and the iNOS-specific inhibitor, 1400W, were used. Figure 2a shows that pretreatment (30 min) with L-NAME or 1400W prevented (P<0.01) the increase in cell proliferation induced by IL-1β, at both 24 and 48 h after stimulation. In this effect L-NAME was more potent than 1400W as it reduced the proliferative responses to IL-1β to less than control values (P<0.05). L-NAME and 1400W given alone did not modify the proliferative response with respect to controls. Parallel results were observed when the effects of L-NAME and 1400W were studied on DNA synthesis (Figure 2b) 24 h after stimulation, which indicated that a cell-cycle arrest in the G1/S-phase transition was most likely the mechanism involved in the antiproliferative effects of these compounds.

Figure 2.

L-NAME (N-ω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester) and 1400W (N-[[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimidamide dihydrochloride) prevented the interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced increase in cell proliferation, DNA synthesis and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation of human astrocytoma cells. Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were pretreated with L-NAME or 1400W, respectively, before stimulation with IL-1β for 1 h. For details in cell proliferation (a) and ERK activity determination (c and d), see legend to Figure 1. DNA synthesis was assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation (b). Values, which represent percentage of radioactivity (c.p.m.) (100%=untreated cells, at 0 h) are mean±s.e.mean from four independent determinations. Statistical analysis comparing IL-1β+L-NAME or IL-1β+1400W vs IL-1β was indicated by asterisks while that comparing IL-1β+L-NAME or IL-1β+1400W vs L-NAME or 1400W was indicated by wickets. Statistics was performed by using one-way ANOVA, followed by Barlett's test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; #P<0.05.

To determine whether NO modulated IL-1β-induced ERK activation, we investigated the effect of IL-1β on ERK activation in the presence of L-NAME or 1400W. As shown in Figures 2c and d, 1 h treatment with IL-1β resulted in significant elevation of ERK phosphorylation, which was prevented by 30 min pretreatment with L-NAME or 1400W (P<0.01). As observed for proliferation data, L-NAME was more potent than 1400W as it reduced ERK responses to less than control value (P<0.05) L-NAME was more potent than 1400W in eliciting this effect as it reduced ERK phosphorylation to less than control values (P<0.05) (Figures 2c and d). Again, these compounds on their own did not influence ERK activation. Collectively, these data suggested that NO-mediated ERK activation induced by IL-1β was part of the mechanism responsible for the cytokine-induced upregulation of cell proliferation. In these effects, both the constitutive and inducible forms of NOS were involved.

Effect of ODQ on IL-1β-induced cell proliferation and ERK1/2 activation in human astrocytoma cells

Many of the actions of NO in different tissues are elicited through activation of the soluble guanylate cyclase, with the resultant production of cGMP. To investigate whether the NO-mediated mitogenic effect of IL-1β was cGMP dependent, we used a specific inhibitor of guanylate cyclase, 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ). Figure 3a shows that 30 min pretreatment with ODQ reduced partially the cell proliferation induced by IL-1β (P<0.05 at 24 h and P<0.01 at 48 h after IL-1β). ODQ given alone did not modify proliferation of the astrocytoma cells with respect to control cultures.

Figure 3.

ODQ (1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one) partially but significantly inhibited both interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) activation and cell division in human astrocytoma cells. Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were pretreated with ODQ, before stimulation with IL-1β for 1 h. For details of cell proliferation (a) and ERK activity (b and c) determination, see legend to Figure 1. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing IL-1β+ODQ with IL-1β by using one-way ANOVA, followed by Barlett's test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

We also tested whether cGMP was involved in IL-1β-induced NO-dependent ERK activation. As shown in Figures 3b and c, 1 h treatment with IL-1β resulted in significant elevation of ERK phosphorylation (P<0.001), and this effect was partly antagonized (P<0.01) when cells were pretreated (30 min) with ODQ. In contrast, ODQ given alone, had no effect on ERK expression with respect to control. Collectively, these data strongly supported the proposition that the IL-1β-induced ERK activation was cGMP dependent. However, the relatively weak inhibition by ODQ of both ERK and cell division, suggested that, in addition to a cGMP-dependent pathway, there was also a major contribution from a cGMP-independent pathway in these effects.

Effect of ryanodine and 2-APB on IL-1β-induced cell proliferation, ERK1/2 activation and apoptosis in human astrocytoma cells

Cells have two principal intracellular receptors responsible for mobilizing stored Ca2+, the inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors and the ryanodine (RY)-sensitive receptors. In many cells, including astrocytes, these occupy specialized compartments of the endoplasmic reticulum. To determine whether Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores was involved in IL-1β-induced proliferation, we investigated the effect of inhibitors of the IP3- and RY-sensitive receptors, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB) and RY, respectively. Neither 2-APB nor RY, on their own, had any effect on proliferation (Figure 4a) This Figure also shows that the stimulation by IL-1β of cell proliferation was completely prevented, at both 24 and 48 h, by 30 min pretreatment with 2-APB or RY. Furthermore, combining RY and 2-APB produced an enhanced inhibition, reducing the proliferative response to IL-1β to less than control values (P<0.01 at 24 and 48 h, respectively). To establish whether apoptotic cell death contributed to this antiproliferative effect, we counted caspase-3+ cells following treatment of IL-1β in the presence of RY plus 2-APB. Results reported in Figure 4b showed that RY plus 2-APB significantly increased the proportion of caspase-3+ cells above control (P<0.001). These values were comparable to those of proliferation decrease induced by the same treatment (see Figure 4a), suggesting that apoptotic cell death fully accounted for the antiproliferative effect induced by the combined treatment.

Figure 4.

Ryanodine (RY) and 2-APB (aminoethoxydiphenylborane) prevented interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced cell proliferation and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation in human astrocytoma cells by inducing apoptosis. Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were pretreated with RY and /or 2-APB before stimulation with IL-1β for 1 h. For details of cell proliferation (a), apoptosis determination (b) and ERK activity (c and d) determination, see legend to Figure 1. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing the following treatments: IL-1β+RY or IL-1β+2-APB or IL-1β+RY+2-APB vs IL-1β (asterisks), and IL-1β+RY+2-APB vs control (wickets) by using one-way ANOVA, followed by Barlett's test. #P<0.05; ##P<0.01; ###P<0.001; **P<0.01.

We also investigated the effects of RY and 2-APB on ERK activation (Figures 4c and d). Pretreatment (30 min) with RY or 2-APB inhibited ERK activation induced by IL-1β (P<0.01) and the combined treatment decreased ERK activation to well below the control value (P<0.01). RY and 2-APB in the absence of IL-1β had no effect. All these data indicate that Ca2+ mobilization from IP3- and RY-sensitive stores mediated the activation of ERK, as well as the cell proliferation, induced by IL-1β.

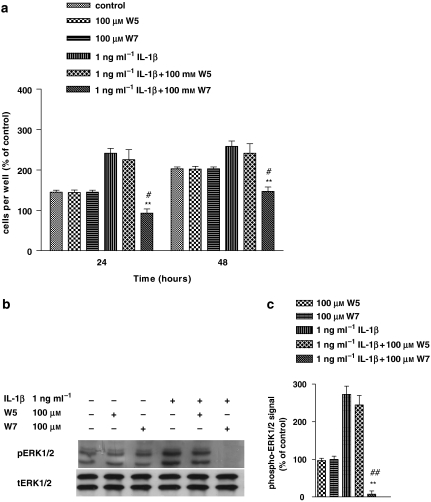

Effect of W7 on IL-1β-induced cell proliferation and ERK1/2 activation in human astrocytoma cells

As CaM plays a crucial role in many Ca2+-mediated cellular responses, we sought to investigate whether the Ca2+-associated mitogenic effect of IL-1β was CaM dependent. To this aim, we functionally blocked CaM by pretreating cells with a specific antagonist, W7, for 1 h before stimulating them with IL-1β for the same time. Figure 5a shows that W7 decreased IL-1β-induced cell proliferation to below control values, at both 24 and 48 h (P<0.01). W7 given alone did not modify cell proliferation. As a control for the specificity of W7, we used its structural analogue W5, which is seven times less potent than W7. At the same concentration, W5 did not affect the mitogenic effect of IL-1β (P=0.5652). As already observed for cell proliferation, W7 completely abolished ERK activation induced by IL-1β, whereas W5 was ineffective (Figure 5b). W7 and W5 administered alone did not modify ERK activity with respect to control. Collectively, these data indicated that the Ca2+-dependent effects involved in ERK activation and cell proliferation induced by IL-1β were mediated by CaM.

Figure 5.

W7 (N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride) prevented interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced cell proliferation and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation in human astrocytoma cells. Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were pretreated with calmodulin (CaM) inhibitors, W7 and its structural analogue W5 (N-(6-aminohexyl)-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride) before stimulation with IL-1β for 1 h. For details of cell proliferation (a) and ERK activity (b and c) determination, see legend to Figure 1. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing the following treatments: IL-1β+W7 or IL-1β+W5 vs IL-1β (asterisks), and IL-1β+W7 vs W7 (wickets) by using one-way ANOVA followed by Barlett's test. #P<0.05; ##P<0.01; **P<0.01.

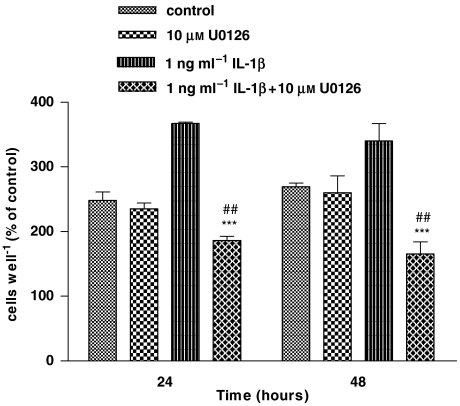

Effect of U0126 on IL-1β-induced cell proliferation in human astrocytoma cells

To further confirm the role of ERK in IL-1β-induced astrocyte proliferation, we investigated the effect of ERK inhibition by U0126, a potent and selective inhibitor of MEK (MAPK kinase) on the mitogenic effect of 1 ng ml−1 IL-1β. As shown in Figure 6, pretreatment with U0126 for 30 min reversed the response to IL-1β and reduced cell proliferation to less than control values, at 24 and 48 h (P<0.001). Given alone, U0126 had no effect on proliferation with respect to control.

Figure 6.

U0126 (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthiol]butadiene) prevented interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced cell proliferation in human astrocytoma cells. Human U-373 astrocytoma cells were pretreated with an MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase) inhibitor, U0126, before stimulation with IL-1β for 1 h. For details of cell proliferation see legend to Figure 1. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing the following treatments: IL-1β+U0126 vs IL-1β (asterisks) and IL-1β+U0126 vs U0126 (wickets) by using one-way ANOVA followed by Barlett's test. ***P<0.001; ##P<0.01.

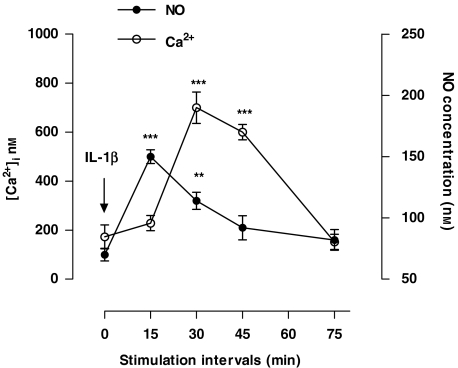

Time course of changes in intracellular Ca2+ and NO concentrations induced by IL-1β in human astrocytoma cells

Data showing involvement of Ca2+ and NO in IL-1β-induced cell proliferation prompted us to investigate the effect of IL-1β on intracellular levels of these messengers. Results reported in Figure 7 showed that both Ca2+ and NO increased transiently, by three to six times, the basal levels over the stimulation period of 75 min. Time course of concentration changes showed that, while NO increased promptly after stimulation, reaching the peak value within 15 min and then declining to basal levels by 75 min, [Ca2+]i presented a 15-min delay before starting to increase and reaching its maximum value, 30 min after stimulation. Thereafter, it declined to basal levels by 75 min. Although these changes in NO and Ca2+ emphasized their involvement in the signal transduction cascade responsible for the mitogenic effect of IL-1β, the delay of the Ca2+ response compared with that of NO, indicated that in the sequence of events leading to the final response, the NO signalling was upstream of the Ca2+ signalling.

Figure 7.

Time course of changes in Ca2+ and NO concentrations induced by interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in human astrocytoma cells. Human U-373MG astrocytoma cells were stimulated for 0, 15, 30, 45 and 75 min with IL-1β (1 ng ml−1). At the end of each period, intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and NO were determined by Fura 2 fluorimetric analysis and electrochemically with an NO-specific electrode, respectively. Values are means±s.e.mean of triplicate determinations from five independent experiments. At each time point, data from treated cells were compared statistically with those of control by one-way ANOVA followed by Barlett's test. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Discussion

Proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, are intimately involved in the generation or modulation of astrogliosis (John et al., 2004). Activated astrocytes produce IL-1β, which in turn, by autocrine and paracrine processes, causes further activation and proliferation of astrocytes (Giulian and Lachman, 1985). To study the mechanism underlying IL-1β-induced astrocyte proliferation, we used a cellular model of human astrocytoma U-373MG cells. Despite its malignant origin, the following considerations led us to use this cell line. First, previous investigations have shown that astrocytoma cells are a very suitable cell culture system for studying molecular signal transduction pathways (Mollace et al., 1993; Lieb et al., 1996); second, our and others' studies have shown that signal transduction pathways in this cell line are similar to that observed in primary astrocytes (Meini et al., 2000; Pahan et al., 2000) and third, with regard to the mitogenic properties of IL-1β, this cell line reacts comparably to primary astrocytes (Giulian and Lachman, 1985; Bertoglio et al., 1987; Kasahara et al., 1990; Yong, 1992).

Using this model, we found that low concentrations of IL-1β increased cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. However, further increase in IL-1β levels resulted in progressive reversal of this effect, indicating that the amount of the cytokine stimulation determined the specificity of the proliferative response. Furthermore, low IL-1β concentrations induced a dose-dependent activation of ERK, which was also progressively downregulated by further increase in the cytokine levels. The strict parallelism between the ERK and the proliferative responses as well as data showing that inhibition of MEK prevented ERK activation and antagonized the mitogenic effect of IL-1β strongly indicated that ERK was part of the mechanism underlying IL-1β-induced cell proliferation.

In attempting to explain the biphasic effect of IL-1β on cell division, we may assume that this cytokine activates distinct and potentially conflicting signals whose balance determine the final proliferative cell fate. Thus, besides the mitogenic p42/44 MAPK pathway, IL-1β might activate different, antiproliferative signalling pathways, which could involve initiation of apoptosis or, alternatively, a cytostatic effect. For instance, IL-1β has been shown to regulate the Fas-FLIP pathway, which in turn can be switched from survival to death signal depending on IL-1β concentration. Indeed, whereas low IL-1β levels activate FLIP leading to increased cell division, high cytokine concentrations downregulate this pathway, directing Fas to death signals (Maedler et al, 2006). With this in mind, it is likely that the Fas-FLIP and ERK pathways, depending on IL-1β level, determine cooperative or otherwise conflicting signals leading to potentiation or reduction of cell division. Alternatively, since IL-1β has been proposed to produce peroxynitrite (Keira et al., 2002), it is likely that increasing IL-1β levels determine elevation of this toxic compound with progressive downregulation of cell proliferation. In line with these hypothesis, we found that reduction in cell division and increase in apoptosis induced by the high IL-1β concentrations were strictly correlated and varied to a similar extent.

A dual role of IL-1β in the context of CNS inflammation has been described. Indeed, data showing IL-1β to contribute to neurodegeneration in CNS inflammatory diseases (Trapp et al., 1998), or otherwise promote remyelination in demyelinating diseases (Mason et al., 2001), lead to the hypothesis that the beneficial vs detrimental effects of IL-1β are probably influenced by a multitude of factors, including the concentrations of cytokine achieved at the site of inflammation.

For an insight into the mechanism that regulates the mitogenic response of IL-1β, we investigated intracellular messengers that could be the likely mediators of the ERK response. Our data showed that pretreatment with L-NAME or the iNOS-specific inhibitor, 1400W, along with an increase in cell proliferation, prevented ERK activation and that L-NAME was more potent than 1400W in eliciting these effects. These data indicated that NO mediated the IL-1β-induced ERK response and that the constitutive and the inducible forms of NOS were involved.

Despite controversy, the role of NO in cell growth regulation is well established. Indeed, whereas growth inhibition appears to be the major effect of NO (Ciani et al., 2004), a significant number of reports describe a proliferative effect (Kim et al., 2003; Bal-Price et al., 2006). This paradoxical behaviour may be reconciled by our and others' observations showing the specificity of the proliferative response being related to the NO levels. Thus, whereas low doses upregulate cell growth, excessive NO levels determine an opposite effect (Meini et al., 2006).

Involvement of the constitutive form of NOS in eliciting ERK response is supported by published data showing that this enzyme is expressed in astroglial cells and proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, upregulating transcription of the constitutive NOS gene (Ma et al., 1994; Czapski et al., 2007). Our data showed that L-NAME, in the presence but not in the absence, of IL-1β, reduced the proliferative response to less than control values. In view of our hypothesis of IL-1β activation of potentially conflicting signals, we may hypothesize that inhibition of the mitogenic ERK pathway by L-NAME would shift the balance in favour of antiproliferative signals resulting in downregulated cell division.

Many effects of NO in different tissues are elicited via activation of soluble guanylate cyclase and cGMP generation. Although in the majority of these actions the precise signalling pathways involved are still primarily unknown, NO-mediated activation of a G kinase is generally accepted as part of the overall mechanism (Fiscus, 2002).

Data showing that the selective inhibitor of guanylate cyclase, ODQ, antagonized ERK activation as well as cell proliferation induced by IL-1β, suggested that a cGMP-dependent pathway is involved in the mechanism underlying these responses. Nevertheless, even though significant, ODQ was a relatively poor inhibitor, indicating that cGMP-independent pathways also participated and possibly were mainly involved in IL-1β effects. Many groups have reported direct interaction of NO with cellular and extracellular proteins, nitrosylation as well as production of NO-derived products, such as peroxynitrite (see Moncada and Bolanos, 2006). Therefore, it is likely that the cGMP-independent part of the NO responses were accounted for by direct interaction of this molecule with specific target proteins relevant for ERK activation. Like NO, Ca2+ is an important signal-transducing molecule that plays a remarkable role in controlling a wide range of cellular functions including cell growth (Villereal and Byron, 1992; Berridge, 1993). Our findings that inhibition of IP3- and RY-sensitive receptors, antagonized IL-1β-induced ERK activation as well as cell proliferation, suggested that Ca2+ mobilization from IP3 and RY stores was part of the mechanism underlying these responses. Ca2+ involvement in IL-1β functions has been previously demonstrated by our in vivo and in vitro studies showing that the pyrogenic/proinflammatory effect of IL-1β was associated with Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum via type I IL-1β receptors and NO production (Palmi et al., 1995, 1996; Palmi and Meini, 2002; Meini et al., 2003). Recently, we have also shown that the amplitude of Ca2+ signalling, via modulation of the strength of ERK activation, regulates proliferation of different cell lines including astrocytes (Meini et al., 2006).

These data are supported by studies showing that removal of Ca2+ by BAPTA/EGTA (Yang et al., 2000) or inhibition of bradykinin receptors responsible for Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores (Yang et al, 2001), significantly attenuate [3H]thymidine incorporation and p42/p44 MAPK activation in IL-1β-treated canine tracheal smooth muscle cells.

Much attention has been focused in recent years on ascertaining the mechanism by which Ca2+ regulates ERK activity. Our findings that W7 prevented IL-1β-induced ERK activation along with cell proliferation indicated that CaM was involved. Molecules which have been described as potential CaM regulators of the ERK–MAPK pathway include the Ras GTP exchange factors, Ras GRF and Ras GRP (Farnsworth et al, 1995; Ebinu et al, 1998). With regards to the present work, it is relevant to point out that Ras/Raf signalling network has been convincingly implicated in promoting proliferative responses as well as differentiation and survival signals through ERK-dependent transactivation of cyclin D (Agell et al., 2002).

Data demonstrating Ca2+ and NO involvement in the mitogenic effect of IL-1β, were further supported by direct measurement of intracellular levels of these two messengers showing that NO and Ca2+ increased transiently and time dependently in response to IL-1β and that the NO response preceded by 15 min that of Ca2+.

All together, these data demonstrated that in human astrocytoma cells, the NO/Ca2+ signalling pathway mediated the mitogenic response of IL-1β via ERK activation and that in the sequence of events leading to the final response, the NO signalling was upstream to that of Ca2+.

Cell proliferation is a hallmark of astrogliosis and IL-1β is clearly the main proinflammatory cytokine involved in this process. Therefore, it is conceivable that the NO/Ca2+ signalling may be part of the mechanism regulating IL-1β-induced astrogliosis. Furthermore, because the role of glial activation in the context of CNS inflammation is controversial, it is likely that the amplitude of the NO/Ca2+ signalling might represent a switch that controls the beneficial vs detrimental effector function of astrogliosis. It is therefore tempting to speculate that modulation of this signalling have important implications in therapeutic approaches to chronic neuroinflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by contribution from the Ministero dell'Università della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MIUR, PRIN 2005 PROT. 2005 06 9071-005), Rome, Italy, the Piano di Ateneo per la Ricerca (PAR 2005-2006), Università di Siena and Fondazione Monte dei Paschi di Siena.

Abbreviations

- 2-APB

aminoethoxydiphenylborane

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- CaM

calmodulin

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- L-NAME

N-ω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one

- RY

ryanodine

- 1400W

N-[[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimidamide dihydrochloride

- W5

N-(6-aminohexyl)-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride

- W7

N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Agell N, Bachs O, Rocamora N, Villalonga P. Modulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by Ca2+ and calmodulin. Cell Signal. 2002;14:649–654. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal-Price A, Gartlon J, Brown GC. Nitric oxide stimulates PC12 cell proliferation via cGMP and inhibits at higher concentrations mainly via energy depletion. Nitric Oxide. 2006;14:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoglio JH, Rimsky L, Kleinerman ES, Lachman LB. B-cell line-derived interleukin 1 is cytotoxic for melanoma cells and promotes the proliferation of an astrocytoma cell line. Lymphokine Res. 1987;6:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani E, Severi S, Contestabile A, Bartesaghi R, Contestabile A. Nitric oxide negatively regulates proliferation and promotes neuronal differentiation trough N-Myc downregulation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4727–4737. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czapski GA, Cakala M, Chalimoniuk M, Gajkowska B, Strosznajder JB. Role of nitric oxide in the brain during lipopolysaccharide-evoked systemic inflammation. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1694–1703. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington CL. Astrocytes as targets for neuroprotective drugs. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:700–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebinu JO, Bottorff DA, Chan EY, Stang SL, Dunn RJ, Stone JC. RasGRP, a Ras guanyl nucleotide-releasing protein with calcium- and diacylglycerol-binding motifs. Science. 1998;280:1082–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emily JG, Arlotta P, Macklis JD. Star-cross'd neurons: astroglial effect on neuronal repair in the adult mammalian CNS. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:238–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng LF, Yu AC, Lee YL. Astrocytic response to injury. Prog Brain Res. 1992;94:353–365. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth CL, Freshney NW, Rosen LB, Gosh A, Greenberg ME, Felg LA. Calcium activation of Ras mediated by neuronal exchange factor Ras-GRF. Nature. 1995;376:524–527. doi: 10.1038/376524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus RR. Involvement of cyclic cGMP and protein kinase G in the regulation of apoptosis and survival neural cells. Neurosignal. 2002;11:175–190. doi: 10.1159/000065431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulian D, Lachman LB. Interleukin-1 stimulation of astroglia proliferation after brain injury. Science. 1985;228:497–499. doi: 10.1126/science.3872478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailer NP, Vogt C, Korf HW, Dehghani F. Interleukin-1β exacerbates and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist attenuates neuronal injury and microglial activation after excitotoxic damage in organotypic hippocampal slices cultures. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2347–2360. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He GW, Liu ZG. Comparison of nitric oxide release and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated hyperpolarization between human radial and internal mammary arteries. Circulation. 2001;104:344–349. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Chen L, Rivieccio MA, Melendez-Vasquez CV, Hartley A, Brosnan CF. Interleukin-1β induces a reactive astroglial phenotype via deactivation of the Rho GTPase–Rock axis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2837–2845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4789-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Lee SC, Brosnan CF. Cytokines: powerful regulators of glial cell activation. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:10–22. doi: 10.1177/1073858402239587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara T, Yagisawa H, Yamashita K, Yamaguchi Y, Akiyama Y. IL-1 induces proliferation and IL6 mRNA expression in a human astrocytoma cell line: positive and negative modulation by cholera toxin and cAMP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keira N, Tatsumi T, Matoba S, Shiraishi J, Yamanaka S, Akashi K, et al. Lethal effect of cytokine-induced nitric oxide and peroxynitrite on cultured rat cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:583–596. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Heo H, Lee HW. Effect of nitric oxide on the proliferation of cultured porcine trabecular meshwork cells. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2003;17:1–6. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2003.17.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb K, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B, Baeuerle PA, Berger M, Bauer J, et al. Interleukin-1β uses common and distinct signaling pathways for induction of the interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor α genes in the human astrocytoma cell line U373. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1496–1503. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Morita I, Murata S. Presence of constitutive type nitric oxide synthase in cultured astrocytes isolated from rat cerebra. Neurosci Lett. 1994;174:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K, Schumann DM, Schulthess FO, Oberholzer J, Bosco D, Berney T, et al. Aging correlates with decreased beta-cell proliferative capacity and enhanced sensitivity to apoptosis: a potential role for Fas and pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1. Diabetes. 2006;55:2455–2462. doi: 10.2337/db05-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JL, Suzuki K, Chaplin DD, Matsuhima GK. Interleukin-1 beta promotes repair of the CNS. J Neurosci Neurobiol. 2001;15:307–309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07046.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meini A, Benocci A, Frosini M, Garcia J, Sgaragli GP, Pessina GP, et al. Potentiation of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization by hypoxia-induced NO generation in rat brain striatal slices and human astrocytoma U-373MG cells and its involvement in tissue damage. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:692–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meini A, Benocci A, Frosini M, Sgaragli GP, Pessina GP, Aldinucci C, et al. Nitric oxide modulation of interleukin-1beta-evoked intracellular Ca2+ release in human astrocytoma U-373MG cells and brain striatal slices. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8980–8986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-08980.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meini A, Blanco JG, Pessina GP, Aldinucci C, Frosini M, Palmi M. Role of intracellular Ca2+ and calmodulin/MAP kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase signalling pathway in the mitogenic and antimitogenic effect of nitric oxide in glia- and neurone-derived cell lines. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1690–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollace V, Colasanti M, Rodino P, Massoud R, Lauro GM, Nistico G. Cytokine-induced nitric oxide generation by cultured astrocytoma cells involves Ca(++)-calmodulin-independent NO-synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;191:327–334. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Bolanos JP. Nitric oxide, cell bioenergetics and neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1676–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Suzuki M, Yajima Y, Suzuki R, Shioda S, Suzuki T. Neuronal protein kinase C gamma-dependent proliferation and hypertrophy of spinal cord astrocytes following repeated in vivo administration of morphine. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahan K, Liu X, Wood C, Raymond JR. Expression of a constitutively active form of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibits the induction of nitric oxide synthase in human astrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2000;472:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01465-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmi M, Frosini M, Sgaragli GP. Interleukin-1β stimulation of 45Ca2+ release from rat striatal slices. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1705–1710. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmi M, Frosini M, Sgaragli GP, Becherucci C, Perretti M, Parente L. Inhibition of interleukin-1 beta-induced pyresis in the rabbit by peptide 204–212 of lipocortin 5. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;281:97–99. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmi M, Meini A. Role of the nitric oxide/cyclic GMP/Ca2+ signaling pathway in the pyrogenic effect of interleukin-1β. Mol Neurobiol. 2002;25:133–147. doi: 10.1385/MN:25:2:133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram K, Benkovic SA, Habert MA, Miller DB, O'Callaghan JP. Induction of gp130-related cytokines and activation of JAK2/STAT3 pathway in astrocytes precedes up-regulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of neurodegeneration: key signaling pathway for astrogliosis in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19936–19947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryadevara R, Holter S, Borgmann K, Persidsky R, Labenz-Zink C, Persidsky Y, et al. Regulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 by astrocytes: links to HIV-1 dementia. Glia. 2003;44:47–56. doi: 10.1002/glia.10266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson RA, Ying W, Kauppien TM. Astrocyte influences on ischemic neuronal death. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:193–205. doi: 10.2174/1566524043479185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamiya Y, Kohsaka S, Toya S, Otani M, Tsukada Y. Immunohistochemical studies on the proliferation of reactive astrocytes and the expression of cytoskeletal proteins following brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 1988;466:201–210. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma K, Baba A, Matsuda T. Astrocytes apoptosis: implication for neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;72:111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani M, Glabinski AR, Touhy VK, Stoler MH, Ester ML, Ransohoff RM. In situ hybridization analysis of glial fibrillary acidic protein mRNA reveals evidence of biphasic astrocyte activation during acute experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:889–896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mork S, Bo L. Axonal transection in the lesion of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY, Pozzan T, Rink TJ. Calcium homeostasis in intact lymphocytes: cytoplasmic free calcium monitored with a new, intracellularly trapped fluorescent indicator. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:325–334. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villereal ML, Byron KL. Calcium signals in growth factor signal transduction. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;119:67–121. doi: 10.1007/3540551921_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woiciechowsky C, Schöning B, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, Stockhammer F, Volk HD. Brain-IL-1β triggers astrogliosis through induction of IL-6: inhibition by propranolol and IL-10. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:BR325–BR330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CM, Chien CM, Hsiao LD, Pan SL, Wang CC, Chiu CT, et al. Mitogenic effect of oxidized low-density lipoprotein on vascular smooth muscle cells mediated by activation of Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1531–1541. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CM, Luo CM, Wang CC, Chiu CT, Chien CS, Lin CC, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha- and interleukin-1beta-stimulated cell proliferation through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in canine tracheal smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:891–899. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong VW. Proliferation of human and mouse astrocytes in vitro: signalling through the protein kinase C pathway. J Neurol Sci. 1992;111:92–103. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]