Abstract

Premature infants are at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a complex condition characterized by impaired alveolar development and increased alveolar epithelial apoptosis. The functional involvement of pulmonary apoptosis in bronchopulmonary dysplasia- associated alveolar disruption remains undetermined. The aims of this study were to generate conditional lung-specific Fas-ligand (FasL) transgenic mice and to determine the effects of FasL-induced respiratory epithelial apoptosis on alveolar remodeling in postcanalicular lungs. Transgenic (TetOp)7-FasL responder mice, generated by pronuclear microinjection, were bred with Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP)-rtTA activator mice. Doxycycline (Dox) was administered from embryonal day 14 to postnatal day 7, and lungs were studied between embryonal day 19 and postnatal day 21. Dox administration induced marked respiratory epithelium-specific FasL mRNA and protein up-regulation in double-transgenic CCSP-rtTA+/(TetOp)7-FasL+ mice compared with single-transgenic CCSP-rtTA+ littermates. The Dox-induced FasL up-regulation was associated with dramatically increased apoptosis of alveolar type II cells and Clara cells, disrupted alveolar development, decreased vascular density, and increased postnatal lethality. These data demonstrate that FasL-induced alveolar epithelial apoptosis during postcanalicular lung remodeling is sufficient to disrupt alveolar development after birth. The availability of inducible lung-specific FasL transgenic mice will facilitate studies of the role of apoptosis in normal and disrupted alveologenesis and may lead to novel therapeutic approaches for perinatal and adult pulmonary diseases characterized by dysregulated apoptosis.

Preterm infants who require assisted ventilation and supplemental oxygen are at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a chronic lung disease of newborn infants associated with significant mortality and long-term morbidity.1,2 The pathological hallmark of BPD in the postsurfactant era is an impairment of alveolar development, resulting in large and simplified airspaces that show little evidence of vascularized ridges (secondary crests) or alveolar septa.3,4 In addition, the lungs of infants with BPD show structurally abnormal microvasculature and variable degrees of interstitial fibrosis.5,6 The BPD currently observed in extremely premature infants has been termed “new” BPD to differentiate this condition from the pathologically and epidemiologically distinct historical BPD, originally described in the late 1960s by Northway and colleagues.7 The latter occurred in less premature infants and was characterized by more severe patterns of acute lung and airway injury.

Many risk factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of BPD. Among these, prematurity, oxygen toxicity, and barotrauma are considered central to a final common outcome.1,8 There are variable contributions of infection/inflammation, glucocorticoid exposure, chorioamnionitis, and genetic polymorphisms.1,9 The precise mechanisms whereby these predisposing conditions result in disrupted alveolar development remain primarily unknown.

Our research efforts in recent years have focused on the role of alveolar epithelial apoptosis in postcanalicular alveolar development. We10,11,12 and others13,14 have demonstrated that moderate and precisely timed alveolar epithelial type II cell apoptosis is an integral component of physiological postcanalicular lung remodeling in mice, rats, and rabbits. Although the exact biological role of apoptosis in alveologenesis remains uncertain, its choreographed occurrence across mammalian species strongly suggests apoptotic elimination of surplus type II cells during perinatal alveolar remodeling is a naturally occurring and developmentally relevant event.

Although moderate and well timed apoptosis appears to represent a physiological phenomenon during postcanalicular lung development, we speculate that exaggerated and/or premature alveolar epithelial apoptosis may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of BPD-associated alveolar disruption. Several recent reports described increased levels of alveolar epithelial apoptosis in the lungs of ventilated preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome or early BPD.15,16,17 The temporal patterns of apoptosis and alveolar disruption in ventilated preterm lungs are suggestive of a causative relationship; however, functional involvement of alveolar epithelial apoptosis in disrupted alveologenesis has not been demonstrated thus far.

In this study, we used a gain-of-function approach to determine the functional role of alveolar epithelial apoptosis in alveolar remodeling. Enhanced respiratory epithelial apoptosis was achieved by means of a transgenic Fas-ligand (FasL) overexpression system. The Fas/FasL receptor-mediated death-signaling pathway is one of the better characterized apoptotic signaling systems.18,19,20 Stimulation of the Fas receptor (CD95/APO1), a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, by its natural ligand FasL or by Fas-activating antibody ligands results in its trimerization and the recruitment of two key signaling proteins, the adapter protein Fas-associated death domain and the initiator cysteine protease caspase-8. Subsequent activation of the effector caspases through mitochondria-dependent or -independent pathways results in activation of caspase-3, the key effector caspase. Activated caspase-3 cleaves a variety of substrates, including DNA repair enzymes, cellular and nuclear structural proteins, endonucleases, and many other cellular constituents, culminating in effective cell death.18,19,20,21

Selection of the Fas/FasL system as inducer of alveolar epithelial apoptosis for this study was a logical choice. First, we previously demonstrated that perinatal murine respiratory epithelial cells are exquisitely sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis in vitro and in vivo.10,22 Furthermore, the Fas/FasL signaling pathway lends itself better to experimental manipulation than other, in particular intrinsic (mitochondrial-dependent) pathways. Finally, the Fas/FasL system has been implicated as critical regulator of alveolar type II cell apoptosis in physiological alveolar remodeling10,11 and in various clinical and experimental models of adult lung injury.23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 It is therefore conceivable that Fas/FasL signaling may play an important role in BPD-associated apoptosis as well.

We previously tested the in vivo effect of Fas-activation in perinatal lungs by systemic administration of a Fas-activating antibody to newborn mice.10 This approach allowed us to demonstrate that perinatal alveolar epithelial cells are susceptible to Fas-mediated apoptosis.10 However, systemic Fas activation resulted in rapid death from liver failure before the effects of exaggerated alveolar apoptosis on alveolar remodeling could be ascertained. To circumvent the deleterious effects of prolonged and systemic FasL exposure, we generated a tetracycline-inducible (tet-on) lung epithelial-specific FasL-overexpressing mouse, adapted from the Tet system of Gossen and colleagues,34 to target apoptosis to respiratory epithelial cells during perinatal lung development.

Our results demonstrate that increased apoptosis of respiratory epithelial cells during postcanalicular alveolar remodeling is sufficient to disrupt alveolar development and results in BPD-like alveolar simplification. These findings support our hypothesis that excessive or premature postcanalicular alveolar epithelial apoptosis is a pivotal event in the pathogenesis of BPD. Elucidation of the role and regulation of postcanalicular alveolar epithelial apoptosis may result in important insights into the regulation of alveologenesis and the pathogenesis of BPD. This, in turn, may open new therapeutic opportunities for the prevention and treatment of this disease, as well as other pulmonary conditions associated with dysregulated alveolar epithelial apoptosis, such as acute lung injury, emphysema, and neoplasia.

Materials and Methods

Generation of a Tetracycline-Dependent Respiratory Epithelium-Specific FasL Transgenic Mouse

The tetracycline-inducible system in vivo consists of two independent transgenic mouse lines, an activator line and a responder line. The activator line expresses the reverse tetracycline responsive transactivator (rtTA) in a tissue- or cell-specific manner, whereas the responder line carries a transgene of interest under control of the tet-operator (TetOp). We selected a tet-on tetracycline-dependent overexpression system to achieve conditional respiratory epithelium-specific FasL transgene expression. In the tet-on system, transgene expression is induced by binding of the tetracycline analogue, doxycycline (Dox) to rtTA, which in turn activates the (tetOp)7-CMV target promoter, activating transcription of the gene of interest.34,35

Tetracycline-dependent transgene expression was targeted to respiratory epithelial cells by using transgenic CCSP-rtTA activator mice in which the rtTA is placed under control of Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP, CC-10) promoter elements.36,37 The specific CCSP-rtTA transactivator mice used for these studies have been shown previously to be robust activators that effectively drive transgene expression not only in nonciliated bronchial epithelial (Clara) cells, but also in alveolar type II cells.36,37,38,39,40,41,42 The 2.3-kb rat CCSP promoter element used in these activator mice is thus expressed differently from the native murine CCSP gene, which is limited to Clara cells.43 Consistent with the endogenous expression pattern of CCSP, which is active from embryonal day 12.5 (E12.5) onward, CCSP-rtTA activator mice have been shown to be particularly suitable for studies of gene function in late gestation and postnatal lungs.37 CCSP-rtTA activator mice, generated in a FVB/N background, were a generous gift from Dr. J. Whitsett37,38 (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH).

To generate (tetOp)7-FasL responder mice, the 943-bp murine FasL cDNA containing the entire coding region of the protein, a kind gift from Dr. S. Nagata44 (Osaka University Medical School, Osaka, Japan), was subcloned between a CMV minimal promoter and bovine growth hormone intronic and polyadenylation sequences in the pTRE2 vector (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (Figure 1). Restriction enzyme digestion and direct sequencing confirmed the orientation of the insert. The transgene was microinjected into fertilized FVB/N oocytes at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Transgenic Core Facility. Founders were identified by transgene-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using upstream primer 5′-CGCCTGGAGACGCCATC-3′ (pTRE2) or 5′-GTGCCATGCAGCAGCCCATGA-3′ (FasL) and downstream primer 5′-CCATTCTAAACAACACCCTG-3′ (pTRE2). Five (tetOp)7-FasL transgenic mouse lines were expanded in our laboratory. Genotype, transgene copy number, and number of integration sites were determined by Southern blot hybridization initially, and monitored by real-time PCR subsequently (FasL primers, PPM02926A; SuperArray Bioscience Corp., Frederick, MD).

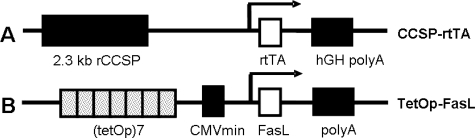

Figure 1.

Constructs used to generate tetracycline-inducible FasL expression in the lung. A: Activator line: the CCSP-rtTA transgene consists of the 2.3-kb rat (r) Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP) promoter, 1.0-kb rtTA coding sequence, and 2.0-kb intronic and polyadenylation sequences from the human growth hormone (hGH).38 B: Responder line: the newly created (TetOp)7-FasL transgene consists of seven copies of the tet operator, flanked by a CMV minimal promoter. The 943-bp murine FasL coding sequence was subcloned downstream from the CMV minimal promoter.

Animal Husbandry and Tissue Processing

Transgenic (tetOp)7-FasL progeny derived from founders A through E were crossed with CCSP-rtTA mice to yield a mixed offspring of double-transgenic (CCSP-rtTA+/(tetOp)7-FasL+) and single-transgenic (CCSP-rtTA+/(tetOp)7-FasL−) littermates. For the sake of brevity, double-transgenic mice will be denoted in the text as CCSP+/FasL+ mice, whereas single-transgenic mice will be denoted as CCSP+/FasL− mice.

Dox (1.0 mg/ml) was added to the drinking water of pregnant and nursing dams between E14 and postnatal day 7 (P7). The progeny (CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL−) were sacrificed at E19, P7 (early alveolarization stage45), or P21 (late alveolarization stage) by pentobarbital overdose. The cages were inspected twice daily to record interval postnatal death. Body and wet lung weights were recorded. Pups were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA using the primers described above. For molecular analysis, lungs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. For morphological studies, fetal lungs were immersion-fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. The lungs of newborn mice were fixed by tracheal instillation of paraformaldehyde at a constant pressure of 20 cm H2O. After overnight fixation, the lungs were dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Controls consisted of Dox-treated single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− littermates, and age-matched CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL− animals that were not treated with Dox. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Protocols were approved through the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Alveolar Type II Cell Isolation and Culture

Alveolar type II cells were isolated from fetal mice (E19) by a modification of the methods described by Corti and colleagues46 and Rice and colleagues,47 as described in detail elsewhere.10 Briefly, type II cells were isolated by protease digestion and differential adherence to CD45- and CD32-coated dishes. After isolation and purification, the cells were resuspended in culture medium (HEPES-buffered Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin). Purity was assessed by modified Papanicolaou stain48 and anti-SP-C immunohistochemistry.10 Viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. After 24 hours, cells were assayed for FasL mRNA expression as detailed below.

Analysis of FasL Gene Expression

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

FasL mRNA levels were quantified by real-time PCR analysis. Total cellular RNA was extracted from whole lung or cell lysates using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA (2 μg) was DNase-treated (Turbo DNA-free kit; Ambion, Austin, TX) and reverse-transcribed using the reverse transcriptase2 first strand kit (SuperArray BioScience) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The cDNA templates were amplified with mouse β-actin (Superarray catalog no. PPM02945A) and FasL (PPM02926A) primer pairs in independent sets of PCR using reverse transcriptase.2 Real-time SYBR Green PCR master mix (Superarray) on an Eppendorf Mastercycler ep realplex (Westbury, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Each sample was run in triplicate, and mRNA levels were analyzed relative to the β-actin housekeeping gene. Relative gene expression ratios were calculated according to the SuperArray-recommended ΔΔCt protocol.49

Immunohistochemical Analysis

The cellular distribution of FasL protein in lung tissues was studied by the streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method using a polyclonal rabbit anti-FasL antibody (Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, MA).10,11 Immunoreactivity was detected with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride. Specificity controls consisted of omission of primary antibody.

Analysis of Apoptosis

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-Mediated dUTP-FITC Nick-End (TUNEL) Labeling

Pulmonary apoptotic activity was localized and quantified by TUNEL labeling, as previously described.10,11 Negative controls for TUNEL labeling were performed by omission of the transferase enzyme. For quantification of TUNEL signals, a minimum of 25 high-power fields were viewed per sample, and the number of apoptotic nuclei per high-power field [apoptotic index (AI)] was recorded. To assess alveolar type II cell apoptosis, TUNEL labeling was combined with immunohistochemical detection of type II cells using a polyclonal anti-prosurfactant protein C (SP-C) antibody (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), as described.11,12 To evaluate Clara cell apoptosis, TUNEL labeling was combined with immunohistochemical detection of Clara cells using a polyclonal anti-CCSP antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Negative controls included omission of the primary antibody, which abolished all staining.

Electron Microscopy

For ultrastructural studies, lung samples were fixed with 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.15 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate/lead citrate and viewed using a Philips 300 electron microscope (Philips, Research, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Western Blot Analysis of Caspase-3 Cleavage

Processing and cleavage of the key Fas-dependent executioner caspase, caspase-3, was assayed by Western blot analysis of lung homogenates, as described elsewhere.10,22 Caspase-3 is expressed as an inactive 32-kDa precursor from which the 17-kDa and 20-kDa subunits of the mature caspase-3 are proteolytically generated during apoptosis. The rabbit polyclonal anticaspase-3 antibody used (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) detects the 17- and 20-kDa cleavage products generated during apoptosis as well as the 32-kDa precursor caspase. Secondary goat antibody was conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and blots developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection assay (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Band intensity was expressed as the combined integrated optical density of the 17- and 20-kDa bands, normalized to the integrated optical density of actin bands (loading control). Specificity controls included preincubation of antibody with blocking peptide.

Analysis of Lung Growth, Alveolarization, and Microvascular Development

Lung growth was assessed by lung weight and lung weight/body weight ratio. In lungs processed for molecular analyses, wet lung weight was recorded. For morphological and morphometric studies, lungs were formalin-fixed by standardized tracheal instillation in situ and lung growth was assessed by determination of inflated lung weight.

Morphometric assessment of growth of peripheral air-exchanging lung parenchyma and contribution of the various lung compartments (airspace versus parenchyma) to the total lung volume was performed using standard stereological volumetric techniques, as previously described.50,51 The inflated lung volume, V(lu), was determined according to the Archimedes principle.52 The areal density of air-exchanging parenchyma, AA(ae/lu), was determined by point-counting based on computer-assisted image analysis. The number of points falling on air-exchanging parenchyma (peripheral lung parenchyma excluding airspace) in random lung fields was divided by the number of points falling on the entire field (tissue and airspace). AA(ae/lu) represents the tissue fraction of the lung and as such is the complement of the airspace fraction AA(air/lu). The total volume of air-exchanging parenchyma, V(ae), was calculated by multiplying AA(ae/lu) by V(lu).

Alveolarization was quantified by computer-assisted morphometric analysis of the mean cord length (MCL) and radial alveolar count (RAC). MCLs were determined by superimposing randomly oriented parallel arrays of lines across randomly selected microscope fields of air-exchanging lung parenchyma (at least 25 random fields per lung) and determining the distance between airspace walls (including alveoli, alveolar sacs, and ducts). The MCL is an indirect estimate of the degree of airspace subdivision by alveolar septa.41 The RAC was determined by counting the number of septa intersected by a perpendicular line drawn from the center of a respiratory bronchiole to the edge of the acinus (connective tissue septum or pleura),53 based on analysis of at least 10 randomly selected lung fields.

The MCL was used to calculate mean volume of airspace units using the following formula: (MCL3 × π)/3. The internal surface area of the lung available for gas exchange was calculated from the formula [(4 × V(lu)]/MCL (adapted from Weibel and Cruz-Orive54) and normalized to body weight to obtain the specific internal surface area. All morphometric assessments were made on coded slides from at least six animals per group by a single observer who was unaware of the genotype or experimental condition of the animal analyzed.

For morphometric analysis of vessel density, sections were immunostained for the presence of Factor VIII [vonWillebrand factor (vWF)] (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), an endothelium-specific marker. The number of Factor VIII-positive vessels (20 to 80 μm in diameter) per high-power field (×20 objective) was counted in 25 randomly selected fields to assess the vessel density, as described by others.55

Data Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or, where appropriate, as mean ± SEM. The significance of differences between groups was determined with the unpaired Student’s t-test or analysis of variance with posthoc Scheffé test where indicated. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. Statview software (Abacus, Berkeley, CA) was used for all statistical work.

Results

Generation of (tetOp)7-FasL Transgenic Mice

Pronuclear microinjection of the (tetOp)7-FasL construct yielded 36 live pups that were screened by PCR. Five transgenic lines (A to E) were established successfully; the transgene copy number of these lines ranged from 2 to 35. The following studies are based on transgenic mouse line D, which has 20 transgene copies and showed intermediate levels of Dox-induced FasL mRNA up-regulation.

Dox Administration Induces Lung-Specific FasL Overexpression in Bitransgenic CCSP+/FasL+ Mice

Pulmonary FasL mRNA Expression

Transgenic (tetOp)7-FasL responder mice (male or female) were crossed with transgenic CCSP-rtTA activator mice of the opposite gender to obtain litters composed of double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ and single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− progeny. Dox was administered to pregnant, and subsequently, nursing dams from E14 to P7. The effect of Dox administration on FasL mRNA expression was studied by quantitative real-time PCR analysis of whole lung homogenates at P7. As shown in Figure 2A, Dox treatment induced a robust more than 30-fold increase in pulmonary FasL mRNA levels in bitransgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice compared with single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− littermates. In the absence of Dox, the FasL mRNA levels of double-transgenic littermates were similar to those of single-transgenic littermates (Figure 2A), indicating that there was no Dox-independent transgene leak.

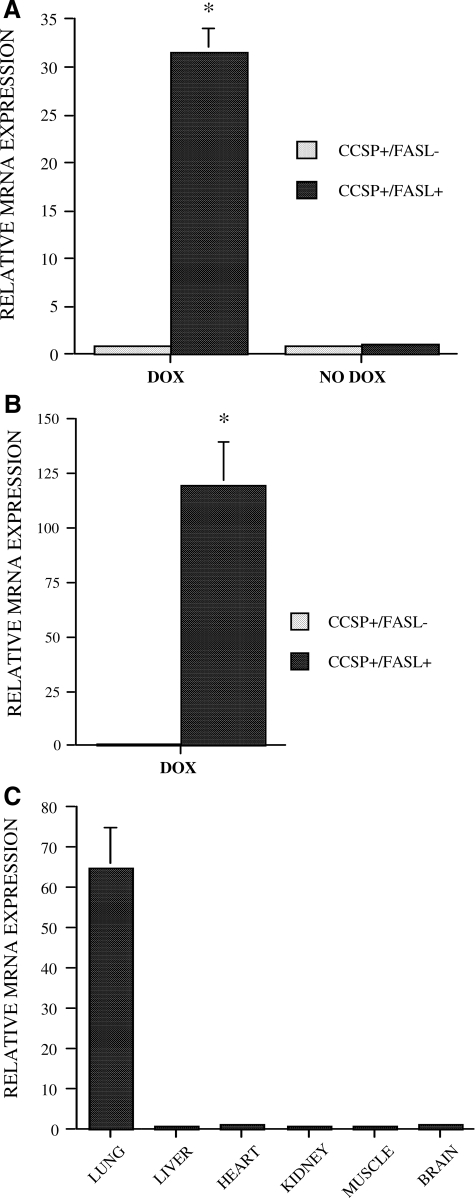

Figure 2.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. A: Analysis of FasL mRNA transcripts in lung homogenates of Dox-treated or non-Dox-treated transgenic mice at P7. *P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL− littermates. B: Analysis of FasL mRNA transcripts in alveolar type II cell lysates from Dox-treated transgenic mice at E19. *P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL− littermates. C: Analysis of FasL mRNA expression in various organs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL mice at P7.

To verify that the CCSP promoter construct is effective in inducing transgene expression in alveolar type II cells, we determined FasL mRNA levels in primary alveolar type II cells isolated from Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL− mice at E19. As seen in Figure 2B, the FasL mRNA levels were significantly more than 100-fold higher in type II cells from Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice compared with single-transgenic littermates. This confirms that the CCSP promoter construct in CCSP-rtTA mice is capable of driving transgene expression in alveolar type II cells, unlike the endogenous murine Clara cell-restricted CCSP promoter. The lung specificity of Dox-induced FasL transgene expression was determined by real-time PCR analysis of FasL mRNA levels in a variety of organs and tissues. As shown in Figure 2C, Dox-induced FasL up-regulation in CCSP+/FasL+ mice was limited to the lung, and not seen in liver, heart, kidneys, muscle, or brain.

FasL Immunohistochemistry

The cellular distribution of FasL protein was determined by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 3). Lungs of Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice (E19) showed intense and diffuse FasL immunoreactivity, localized to bronchial epithelial cells, alveolar epithelial cells, and intra-alveolar cellular debris (Figure 3A). In single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL littermates, FasL immunostaining was modest and localized to bronchial epithelial cells and scattered alveolar epithelial cells that were morphologically consistent with alveolar type II cells (Figure 3B). Omission of the primary antibody abolished all immunoreactivity (Figure 3C).

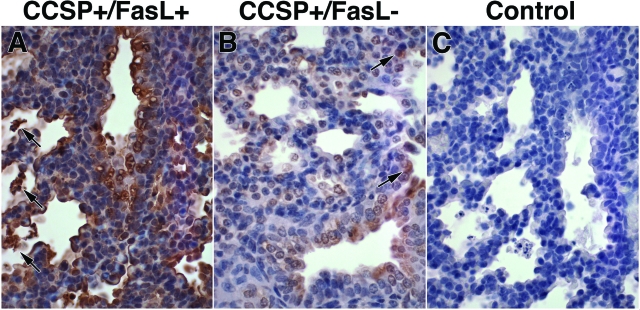

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of FasL protein expression. A: Representative FasL immunostaining of lungs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice at E19 showing diffuse and intense FasL immunoreactivity, localized to alveolar epithelial cells morphologically consistent with type II cells, intra-alveolar cellular debris (arrows), and bronchial epithelial cells. B: Lungs of single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− littermates showing modest FasL immunolabeling in bronchial epithelial cells and scattered alveolar epithelial type II cells (arrows). C: Negative control (omission of primary antibody). Anti-FasL immunostaining by ABC method, hematoxylin counterstain. Original magnifications, ×400.

FasL Overexpression in Dox-Treated Bitransgenic CCSP+/FasL+ Mice Is Associated with Increased Postnatal, but Not Fetal Lethality

To assess the effects of FasL transgene overexpression on antenatal and postnatal viability, we determined the proportions of double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ and single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− progeny at E19 and at P7. CCSP-rtTA mice are homozygous and (TetOp)7-FasL mice hemizygous for their respective transgenes. According to Mendelian laws of inheritance, we would therefore expect equal proportions of double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ and single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− progeny in the absence of a lethal effect.

At E19 (late gestation), the ratios of double- and single-transgenic Dox-treated fetuses were approximately equal, indicating that the CCSP+/FasL+ double-transgenic status does not confer lethal effects in utero (Table 1). At P7, however, CCSP+/FasL+ pups accounted for only ∼30% of Dox-treated progeny, suggestive of increased postnatal lethality in Dox-exposed double-transgenic mice (Table 2). The body weight of Dox-treated double-transgenic mice at P7 tended to be less than that of single-transgenic littermates, whereas their lung weight tended to be larger (Table 2). This resulted in significantly larger lung weight/body weight ratios in Dox-treated double-transgenic mice compared with single-transgenic littermates. In the absence of Dox, the ratios of double- and single-transgenic progeny at P7 were equal, indicating that the double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ status is not deleterious without Dox-exposure. The body weights of Dox-treated transgenic animals were significantly lower than those of non-Dox-treated animals of the same genotype, suggesting that Dox affects postnatal somatic growth (Table 2). The body weights of Dox-treated or non-Dox-treated pups were not affected by the maternal genotype (CCSP-rtTA versus (tetOp)7-FasL).

Table 1.

Genetic and Biometric Characteristics of Dox-Treated Transgenic CCSP/FasL Mice at E19

| Age | E19 | |

| Genotype | CCSP+/FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− |

| Fraction of living offspring | 24/51 (47%) | 27/51 (53%) |

| Body weight (g) | 1.11 ± 0.11 (24) | 1.11 ± 0.11 (27) |

| Lung weight (g) | 0.023 ± 0.006 (17) | 0.026 ± 0.006 (21) |

| Lung weight/body weight (%) | 2.16 ± 0.54 (17) | 2.42 ± 0.01 (21)* |

Lung weights at E19 reflect wet lung weights. Values represent mean ± SD.

P < 0.05 versus CCSP+/FasL+ littermates (Student’s t-test).

Table 2.

Genetic and Biometric Characteristics of Dox-Treated or Non-Dox-Treated Transgenic CCSP/FasL Mice at P7

| Age P7

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dox

|

No Dox

|

|||

| CCSP+/FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− | CCSP+/FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− | |

| Fraction of living offspring | 22/72 (31%) | 50/72 (69%) | 8/16 (50%) | 8/16 (50%) |

| Body weight (g) | 2.78 ± 0.48 (22) | 2.99 ± 0.47 (50) | 3.66 ± 0.27 (8)‡ | 3.65 ± 0.17 (8)‡ |

| Lung weight (wet) (g) | 0.068 ± 0.009 (5) | 0.062 ± 0.004 (8) | 0.057 ± 0.002 (4) | 0.057 ± 0.008 (4) |

| Lung weight (wet)/body weight (%) | 2.17 ± 0.45 (5) | 1.76 ± 0.21 (8)* | 1.63 ± 0.15 (4) | 1.49 ± 0.18 (4) |

| Lung weight (infl) (g) | 0.21 ± 0.03 (5) | 0.19 ± 0.03 (11) | 0.18 ± 0.01 (3) | 0.18 ± 0.01 (3) |

| Lung weight (infl)/body weight (%) | 7.32 ± 0.65 (5) | 6.15 ± 0.73 (11)† | 4.98 ± 0.09 (3)‡ | 4.77 ± 0.25 (3)‡ |

Values represent mean ± SD.

P < 0.05 versus CCSP+/FasL+ littermates;

P < 0.01 versus CCSP+/FasL+ littermates;

P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated animals of same genotype (Student’s t-test).

FasL Overexpression in Dox-Treated Bitransgenic CCSP+/FasL+ Mice Induces Increased Pulmonary Apoptosis

Lung Morphology and TUNEL Analysis at E19 and P7

Lungs of double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice treated with Dox from E14 on and examined at E19 and P7 showed abundant cellular debris and detached apoptotic cells within the airspaces (Figure 4, A and E). At P7, the intra-alveolar cellular material was admixed with numerous macrophages. Pyknotic nuclei within the bronchial epithelium were readily observed at both time points (Figure 4, A and E). The lungs of single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− littermates appeared unremarkable and showed only rare single cells in the airspaces (Figure 4, B and F).

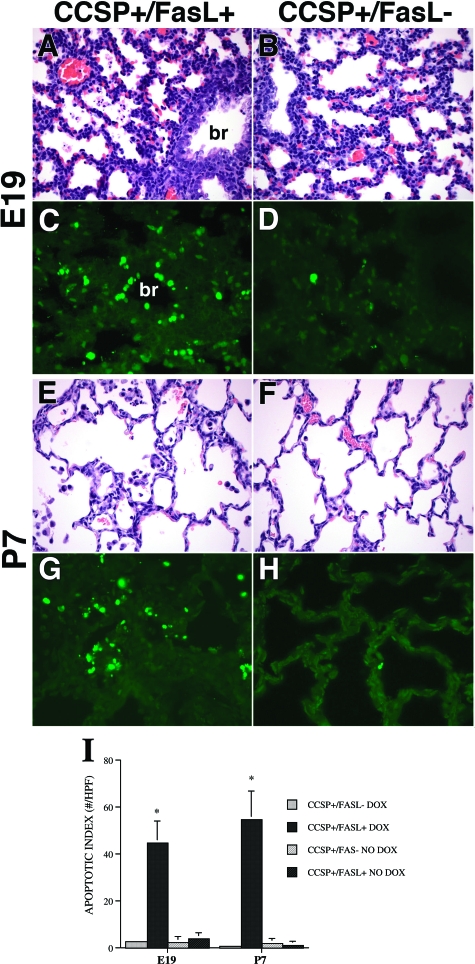

Figure 4.

Morphology and TUNEL labeling of lungs of Dox-treated transgenic mice at E19 and P7. A: CCSP+/FasL+ lungs at E19 (late gestation, saccular stage of development) showing abundant cellular debris within the airspaces and pyknotic nuclei within the bronchial epithelium. Br, bronchus. B: Lungs of CCSP+/FasL− littermate of A without histopathological evidence of apoptosis. C: TUNEL labeling of Dox-treated CCSP+/Fas+ lungs at E19 showing abundant aggregates of TUNEL-positive nuclear material within the alveolar septa and airspaces. In addition, TUNEL-positive nuclei are noted within the bronchial epithelium. Br, bronchus. D: Lungs of a CCSP+/FasL− littermate containing only rare TUNEL-positive nuclei, localized to peribronchial and perivascular stromal cells. E: CCSP+/FasL+ lungs at P7 showing relatively large airspaces, little evidence of secondary crest formation, and abundant intra-alveolar macrophages admixed with apoptotic nuclear debris. Septa appear relatively hypercellular. F: Lungs of CCSP+/FasL− littermate of C showing thinner septa, more advanced secondary crest formation (early alveolar stage), and only scant intra-alveolar macrophages. G: CCSP+/FasL+ lungs at P7 showing persistently high TUNEL positivity, mainly within intra-alveolar cellular debris. H: Lungs of CCSP+/FasL− littermate at P7 showing very low TUNEL reactivity. I: Apoptotic index. Values represent mean ± SD of at least four animals per group. *P < 0.001 versus Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL− littermates. H&E staining (A, B, E, F); TUNEL-FITC labeling (C, D, G, H). Original magnifications, ×400.

TUNEL labeling highlighted the dramatic increase in apoptotic activity in lungs of Dox-treated double-transgenic mice (Figure 4, C and G). The increased TUNEL activity in Dox-exposed double-transgenic mice was noted in cellular debris within the airspaces and in bronchial epithelial cells. The apoptotic activity in single-transgenic lungs was low at both E19 and P7, and mainly localized to peribronchial and perivascular stromal cells (Figure 4, D and H). In the absence of Dox, the apoptotic activity of CCSP+/FasL+ mice was very low and similar to that of single-transgenic littermates (Figure 4I).

Interval studies determined that virtually all (>95%) Dox-exposed mice that died between birth and P7 had the double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ genotype. Histopathological studies of the lungs of these animals showed that their airspaces were massively occluded by cellular debris admixed with apoptotic nuclear material (not shown). Based on this pathological evidence and the gross appearance of the moribund pups, the disproportionate postnatal lethality of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice was attributed to respiratory failure.

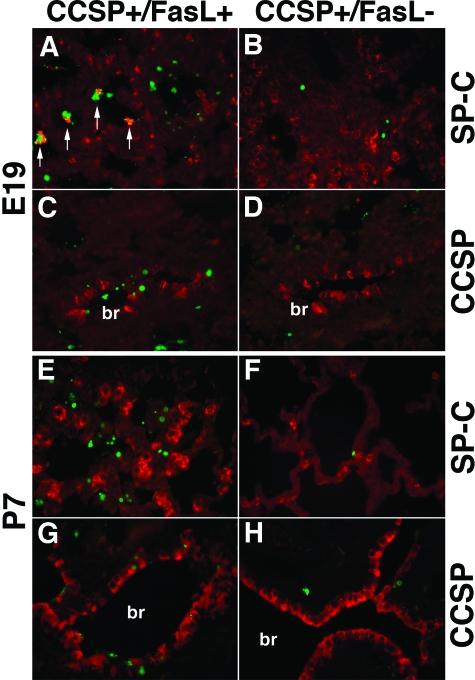

TUNEL Analysis Combined with Anti-SP and Anti-CCSP Immunolabeling at E19 and P7

To determine the identity of the apoptotic cells, TUNEL labeling was combined with anti-SP-C or anti-CCSP immunohistochemistry. At E19, lungs of Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice showed frequent association of TUNEL-positive nuclei with SP-C immunoreactive cellular material within the intra-alveolar debris, suggesting that a large proportion of apoptotic cells were type II cells (Figure 5A). In single-transgenic littermates, the scant pulmonary apoptotic activity was mainly seen in SP-C-negative peribronchial and perivascular stromal cells (Figure 5B). Combination of TUNEL labeling with anti-CCSP staining revealed brisk apoptotic activity in CCSP-positive bronchial epithelial Clara cells in double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice (Figure 5C), whereas apoptotic activity of Clara cells was negligible in single-transgenic mice (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

TUNEL labeling combined with anti-prosurfactant protein C (SP-C) or anti-Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP) immunohistochemistry. A–D: Lungs of Dox-treated transgenic mice at E19. A: Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ lungs at E19 showing co-localization of SP-C-positive cellular material with TUNEL-positive nuclei in intra-alveolar cellular debris (arrows). B: Lungs of littermate of A showing low apoptotic activity in SP-C-negative, non-type II cell. Nonapoptotic SP-C-positive type II cells are noted along the alveolar walls. C: Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ lungs at E19 showing numerous TUNEL-positive nuclei in CCSP-positive bronchial epithelial (Clara) cells. D: Lung of littermate of animal in E showing rare TUNEL positivity, localized to CCSP-negative stromal cells. E–H: Lungs of Dox-treated transgenic mice at P7. E: Lungs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mouse at P7 showing abundant SP-C-negative apoptotic material within the alveoli and within the bronchial lining. Large numbers of intensely SP-C-positive, TUNEL-negative type II cells are noted within and along the alveolar septa. F: Single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− lungs at P7 showing only scattered TUNEL positivity, mainly in SP-C-negative stromal cells. G: CCSP+/FasL+ lung at P7 showing TUNEL-positive nuclei in and around bronchial epithelial cells. H: Single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− lung at P7 showing occasional apoptotic activity in CCSP-negative cells. br, bronchus. TUNEL: FITC labeling (green), anti-SP-C and anti-CCSP: Cy-3 labeling (red). Original magnifications, ×400.

At P7, abundant apoptotic cellular debris remained present within the airspaces of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice (Figure 5E). At this time point, most intra-alveolar apoptotic nuclei were devoid of identifiable cellular characteristics. Strikingly, lungs of CCSP+/FasL+ mice at P7 showed large numbers of intensely SP-C-immunoreactive alveolar type II cells within the alveolar walls. As seen in Figure 6E, these hyperplastic type II cells were virtually uniformly TUNEL-negative.

Figure 6.

Electron microscopic analysis of lungs of Dox-treated transgenic mice. A: Representative electron micrograph of the alveolar wall of Dox-treated single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− mice (E19). A well preserved alveolar type II cell is noted, characterized by lamellar bodies, subnuclear glycogen pools, and abundant microvilli. Myelin whorls, representing surfactant lipids, are present within the airspace (arrow). B: Higher magnification of alveolar type II cell in A showing typical surfactant-containing lamellar bodies (arrows). C: Representative electron micrograph of lungs of Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice showing several cells detached from the alveolar wall. The nuclei show characteristic ultrastructural features of apoptosis, including fragmentation, pyknosis, and chromatin condensation. One dying cell contains residual lamellar bodies. D: Higher magnification of cells in C showing the presence of cytoplasmic lamellar bodies (arrows), identifying the dying cells as alveolar type II cells. E: Lung of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mouse showing numerous apoptotic nuclei within the airspaces, associated with pools of degenerating myelin-like material. Endothelial cells (end) appear viable. F: Bronchial epithelium of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mouse showing a row of apoptotic cells with typical peripheral condensation of chromatin (arrows). An apoptotic nucleus, presumably phagocytosed, is seen in the cytoplasm of a non-Clara bronchial epithelial cell (asterisk).

TUNEL labeling combined with anti-CCSP immunostaining at P7 demonstrated increased numbers of TUNEL-positive nuclei in the bronchial epithelium of double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice, both in CCSP-positive Clara cells and in neighboring CCSP-negative bronchial epithelial cells (Figure 5G). The apoptotic activity in Dox-treated single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− littermates was low, and preferentially localized to SP-C-negative and CCSP-negative stromal cells around large-sized vascular or bronchial structures (Figure 5, F and H).

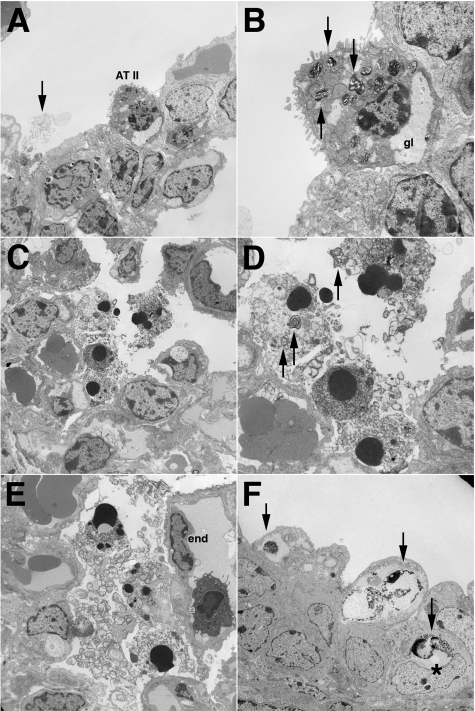

Electron Microscopy

Ultrastructural analysis of the lungs of Dox-treated single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− mice (E19) revealed frequent, well preserved alveolar type II cells that were readily identified by their cuboidal shape, prominent microvilli, and the presence of cytoplasmic lamellar bodies and glycogen pools (Figure 6, A and B). The alveolar space overlying the alveolar type II cells often showed the presence of tubular myelin, consistent with surfactant lipid material.

In contrast, the lungs of Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ littermates showed a striking paucity of recognizable alveolar type II cells. Instead, these lungs contained large aggregates of detached cells within the airspaces that were often associated with tubular myelin-like material. These detached intra-alveolar cells showed the characteristic ultrastructural features of apoptosis, including cell shrinkage and peripheral or diffuse chromatin condensation of the nuclei (Figure 6, C–E). Definitive identification of the detached apoptotic cells was often impossible because of advanced cellular degradation. In better preserved apoptotic cells, however, typical cytoplasmic lamellar bodies could be seen, allowing identification of these cells as alveolar type II cells (Figure 6D). Apoptotic nuclei with typical peripheral chromatin condensation were also seen in nonciliated bronchial epithelial (Clara) cells (Figure 6F). Apoptotic nuclei were occasionally present in adjacent nonapoptotic bronchial epithelial cells, suggestive of phagocytotic clearance of apoptotic Clara cells by neighboring cells. Apoptotic nuclei were not observed in other bronchial epithelial cells, endothelial cells, or interstitial stromal cells.

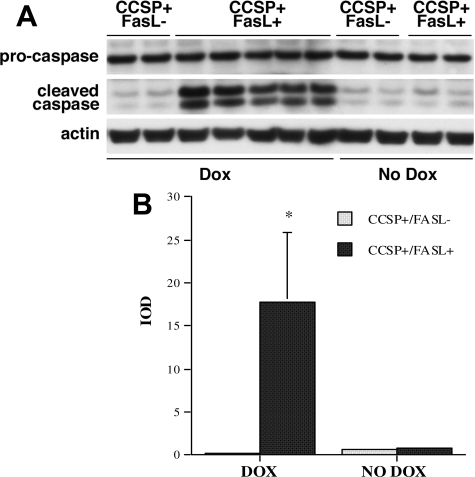

Western Blot Analysis of Caspase-3 Cleavage

Processing and cleavage of caspase-3, the main executioner of the Fas-dependent apoptotic machinery, was assessed by Western blot analysis using an antibody specific for both procaspase-3 and the active caspase-3 cleavage products. Consistent with Fas-mediated cell death, Dox-exposed CCSP+/FasL+ lungs showed cleavage of procaspase-3 and increased levels of the immunoreactive 17- and 20-kDa active subunits of caspase-3 (Figure 7). In contrast, levels of the caspase split products were negligible in lung homogenates of CCSP+/FasL− littermates. In the absence of Dox, caspase-3 cleavage was minimal and similar in double- and single-transgenic mice.

Figure 7.

Western blot analysis of caspase-3 cleavage. A: Western blot analysis of caspase processing in lung lysates of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL− mice at P7. In double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice, Dox administration resulted in increased levels of the 17- and 20-kDa subunits of caspase-3. Cleavage products were negligible in Dox-treated single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− littermates and non-Dox-treated animals. B: Densitometry of caspase cleavage by Western blot analysis. Values represent combined integrated optical density of 17-kDa and 20-kDa bands as mean ± SD. At least four animals were studied per group. *P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL−.

FasL-Induced Alveolar Epithelial Apoptosis Disrupts Alveolar and Microvascular Development in Dox-Treated Bitransgenic CCSP+/FasL+ Mice

To determine the effects of FasL-induced apoptosis on alveolar remodeling, lungs of transgenic mice were studied at P21 after Dox administration from E14 to P7. The ratios of surviving Dox-treated double- and single-transgenic progeny at P21 (29% double transgenic, 71% single transgenic) were similar to those observed at P7, suggesting that no additional mortality occurred after discontinuation of the Dox treatment (Table 3). By P21, the body weights were similar in Dox-treated double- and single-transgenic animals and equivalent to those of animals not exposed to Dox (Table 3). The lung weight/body weight ratio (either wet or inflation-fixed) was significantly larger in Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice than in CCSP+/FasL− littermates (P < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genetic and Biometric Characteristics of Dox-Treated or Non-Dox-Treated Transgenic CCSP/FasL Mice at P21

| Age P21

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dox

|

No Dox

|

|||

| CCSP+/FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− | CCSP+FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− | |

| Fraction of living offspring | 10/35 (29%) | 25/35 (71%) | 7/13 (54%) | 6/13 (46%) |

| Body weight (g) | 10.25 ± 0.96 (10) | 10.96.± 1.45 (25) | 10.16 ± 0.58 (7) | 9.85 ± 0.24 (6) |

| Lung weight (wet) (g) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (3) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (7) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (4) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (3) |

| Lung weight (wet)/body weight (%) | 1.36 ± 0.06 (3) | 1.21 ± 0.05 (7)* | 1.14 ± 0.15 (4) | 1.14 ± 0.13 (3) |

| Lung weight (infl) (g) | 0.50 ± 0.05 (6) | 0.43 ± 0.03 (16) | 0.39 ± 0.03 (3)† | 0.35 ± 0.01 (3)† |

| Lung weight (infl)/body weight (%) | 4.68 ± 0.48 (6) | 3.78 ± 0.42 (16)* | 3.95 ± 0.18 (3)‡ | 3.57 ± 0.05 (3) |

Values represent mean ± SD.

Lung weight (infl): lung weight after standardized inflation and fixation.

P < 0.01 versus CCSP+/FasL+ littermates;

P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated animals of same genotype;

P < 0.05 versus Dox-treated animals of same genotype (Student’s t-test).

The total lung volume, V(lu), and the V(lu)/body weight ratio were significantly larger in Dox-treated double-transgenic mice than in single-transgenic littermates (P < 0.01) (Table 4). Computer-assisted stereological volumetry was applied to determine the relative contributions of the various lung compartments (specifically, peripheral air-exchanging parenchyma versus airspace) to the observed total lung volume. The areal density of air-exchanging parenchyma, AA(ae/lu), representing the parenchymal tissue fraction, was significantly lower in double-transgenic mice. The total volume of air-exchanging parenchyma, V(ae), which takes into account both AA(ae/lu) and V(lu), was similar in double- and single-transgenic mice, indicating that the increased V(lu) in double-transgenic mice was attributable to distension of the airspaces rather than actual tissue growth.

Table 4.

Morphometric Analysis of Lungs of Dox-Treated or Non-Dox-Treated Transgenic CCSP/FasL Mice at P21

| Age P21

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dox

|

No Dox

|

|||

| CCSP+/FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− | CCSP+/FasL+ | CCSP+/FasL− | |

| V(lu) (μl) | 471 ± 52 (6) | 407 ± 30 (16)* | 372 ± 26 (3)‡ | 334 ± 8 (3)‡ |

| V(lu)/body weight (ml/g) | 4.44 ± 0.46 (6) | 3.59 ± 0.40 (16)* | 3.75 ± 0.20 (3)† | 3.39 ± 0.05 (3) |

| AA(ae/lu) (%) | 28.06 ± 2.51 (6) | 33.22 ± 3.17 (16)* | 32.04 ± 1.74 (3)† | 33.71 ± 1.13 (3) |

| AA(air/lu) (%) | 71.94 ± 2.51 (6) | 66.78 ± 3.17 (16)* | 67.96 ± 1.74 (3)† | 66.29 ± 1.13 (3) |

| V(ae) (μl) | 131 ± 9 (6) | 135 ± 18 (16) | 119 ± 9 (3) | 113 ± 6 (3) |

| V(aspunit) (μl × 10−6) | 42.9 ± 8.8 (6) | 15.5 ± 4.1 (16)* | 6.6 ± 0.9 (3)‡ | 7.1 ± 1.2 (3)‡ |

| ISA (cm2) | 553 ± 90 (6) | 685 ± 66 (16)* | 808 ± 68 (3)‡ | 711 ± 55 (3) |

| SISA (cm2/g) | 52.2 ± 8.7 (6) | 59.7 ± 8.3 (16) | 81.5 ± 7.2 (3)‡ | 72.0 ± 5.0 (3)† |

Values represent mean ± SD. V(lu), lung volume; AA(ae/lu), fraction of air-exchanging parenchyma; AA(air/lu), airspace fraction; V(ae), volume of air-exchanging parenchyma; V(aspunit), volume of airspace unit; ISA: internal surface area; SISA, specific internal surface area.

P < 0.01 versus CCSP+/FasL+ littermates;

P < 0.05 versus Dox-treated animals of same genotype;

P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated animals of same genotype (Student’s t-test).

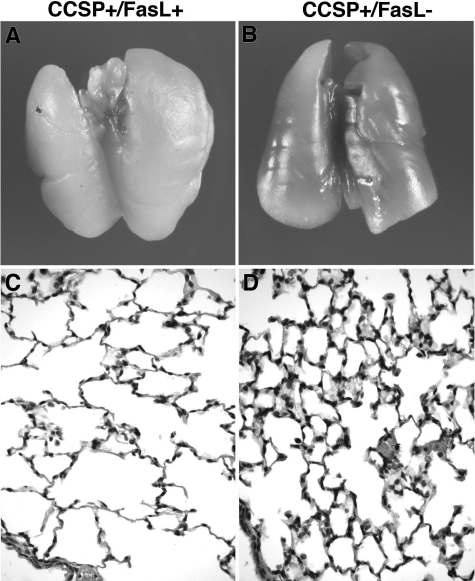

The formalin-inflated lungs of Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice at P21 appeared large and pale compared with those of CCSP+/FasL− littermates (Figure 8, A and B). Microscopically, lungs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice displayed marked alveolar disruption characterized by large-sized simplified airspaces with a striking paucity of alveolar septation or secondary crest formation, thus faithfully mimicking the alveolar pathology of human BPD (Figure 8C). Small macrophage collections were occasionally noted. There was no histopathological evidence of fibrosis or bronchial epithelial injury. Lungs of Dox-treated single-transgenic mice at P21 showed more advanced alveolarization, characterized by a more complex network of abundant small-sized polygonal alveoli, separated by delicate alveolar septa (Figure 8D). Although more complex than in Dox-treated double-transgenic mice, alveolarization appeared less advanced in Dox-treated single-transgenic mice compared with non-Dox-treated transgenic mice (not shown).

Figure 8.

Gross and microscopic appearance of lungs of Dox-treated transgenic mice at P21. A and B: Macroscopic appearance of formalin-inflated lungs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL− mice at P21. Lungs of double-transgenic pups appeared large and pale with obtunded edges. C and D: Representative photomicrographs of lungs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL− mice at P21. C: CCSP+/FasL+ lungs at P21 showing large-sized simple alveolar spaces separated by thin alveolar septa. Small macrophage collections are present. D: Lungs of CCSP+/FasL− littermate of C showing a complex network of small-sized alveoli (advanced alveolar stage). H&E staining. Original magnifications, ×400.

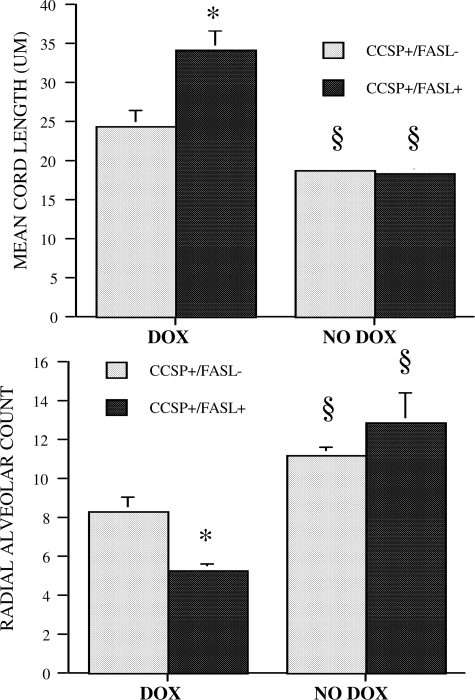

To estimate the degree of alveolarization in transgenic mice, the MCL and RAC were determined. As shown in Figure 9, the MCL was significantly larger (P < 0.01), and the RAC significantly smaller (P < 0.01) in Dox-treated double-transgenic mice compared with single-transgenic littermates, confirming the presence of decreased alveolar septation in Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice. Without Dox, the MCL and RAC of single- and double-transgenic animals were similar (Figure 9). The calculated volume of the individual airspace units was almost threefold larger in Dox-treated double-transgenic mice compared with single-transgenic mice (P < 0.01) (Table 4). The lung surface area available for gas exchange, estimated by calculation of the internal surface area, was significantly diminished in Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice compared with single-transgenic littermates, although this difference was attenuated after normalization to body weight (Table 4).

Figure 9.

MCL and RAC of lungs of Dox-treated or non-Dox-treated transgenic mice at P21. Values are mean ± SD of at least six animals studied per group. *P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL− littermates; §P < 0.01 versus Dox-treated animals of same genotype (Student’s t-test).

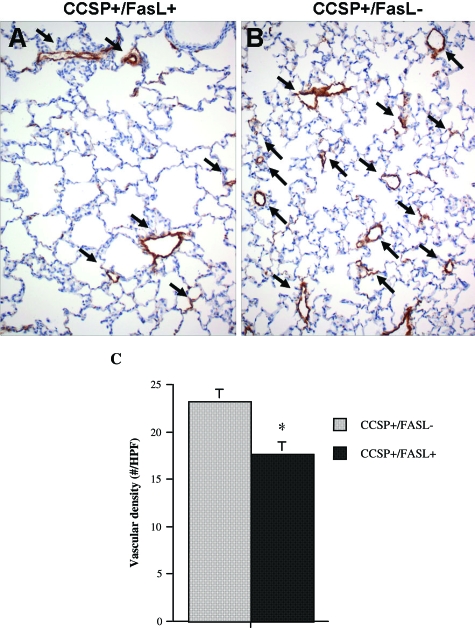

In the absence of Dox, the morphometric assessment of lung growth and alveolarization was similar in double- and single-transgenic animals, indicating that the presence of the (TetOp)7-FasL transgene does not have Dox-independent effects on lung development. Compared with non-Dox-treated single-transgenic CCSP+/FasL− mice, Dox-treated single-transgenic animals had significantly larger V(lu), MCL, volume of airspace unit, and specific internal surface area, as well as significantly smaller RAC, indicative of Dox-related effects on alveolarization (Figure 9 and Table 4). To assess the effect of FasL-mediated respiratory epithelial apoptosis on pulmonary microvascular development, the vascular density was determined, as described by others.55 Vessel density was reduced by 25% in Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice compared with single-transgenic littermates (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Pulmonary vascular density of Dox-treated transgenic mice at P21. Representative Factor VIII (von Willebrand factor) immunostaining of lungs of Dox-treated double- and single-transgenic littermates. The density of vessels, highlighted by staining for Factor VIII, is lower in lungs of double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice (A) compared with CCSP+/FasL− littermates (B). C: Vascular density, expressed as number of vessels (20 to 80 μm) per ×20 high-power field. Values are mean ± SD of four animals studied per group. *P < 0.05 versus Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL− littermates (Student’s t-test).

Discussion

In this study, we used a gain-of-function approach to determine the effects of alveolar epithelial apoptosis on postcanalicular alveolar remodeling. We generated a tetracycline-inducible lung epithelial-specific FasL-overexpressing mouse, adapted from the Tet system of Gossen and colleagues,34 to target apoptosis to respiratory epithelial cells during perinatal lung development. We demonstrated that increased alveolar epithelial apoptosis during postcanalicular lung remodeling is sufficient to disrupt alveolar development and results in a pattern of alveolar simplification that closely mimics the pulmonary pathology of human BPD.

These findings establish a solid causative relationship between alveolar epithelial apoptosis and disrupted alveolarization and support our hypothesis that excessive or premature alveolar epithelial apoptosis is a pivotal event in the pathogenesis of BPD that links the known risk factors of BPD to the final common outcome: impaired alveolar development. Accumulating clinical and experimental evidence shows that the major predisposing factors implicated in BPD, including hyperoxia/oxygen toxicity,22,56,57 mechanical distension (stretch),12,58,59,60,61 and proinflammatory factors26,62 are capable of inducing alveolar epithelial apoptosis. The molecular signaling pathways regulating alveolar epithelial apoptosis in early BPD remain undetermined, but likely include both receptor-mediated (extrinsic) and mitochondrial-dependent (intrinsic) death signaling systems.

The precise mechanisms by which exaggerated or premature alveolar epithelial apoptosis induces alveolar disruption remain to be determined. First, the alveolar arrest may simply be attributable to numerical loss of alveolar type II cells during crucial time points of alveolar remodeling. Alveolar type II cells ensure adequate surfactant production around birth and serve as the proliferative source for alveolar type I cells that line most of the alveolar surface.63 It is therefore reasonable to speculate that accumulation of a critical mass of alveolar type II cells is essential for normal postnatal lung remodeling. Interestingly, several lines of evidence in humans and experimental models link apoptosis with lung destruction in emphysematous adult lungs,64,65,66,67,68,69,70 suggesting that in fully developed lungs as well, type II cell loss is capable of disrupting the alveolar architecture.

Second, reactive type II cell hyperplasia after initial type II cell apoptosis may contribute, paradoxically, to disrupted alveolar remodeling. Reactive type II cell hyperplasia is a characteristic feature of most forms of acute lung injury, including the early stages of lung injury in newborns. In the present study, FasL overexpression in fetal lungs caused massive apoptosis of alveolar type II cells, resulting in near-total eradication of these cells by E19. By P7, however, the alveoli were repopulated by large numbers of strongly SP-C-immunoreactive alveolar type II cells. This newly emerging population of hyperplastic alveolar type II cells was strikingly refractory to apoptosis, despite continued Dox exposure and pulmonary FasL overexpression. This suggests that, at least with respect to Fas sensitivity, the second-generation type II cells are phenotypically different from the original, naïve type II cells. The cellular ontogeny and phenotypic characteristics of the repopulating type II cells remain to be determined. It is possible, however, that the hyperplastic type II cells may also differ from naïve type II cells in other aspects affecting alveologenesis, such as the epithelial-mesenchymal and epithelial-endothelial interactions required for alveolar septation.

Finally, apoptosis-induced alveolar disruption may be mediated by the action of macrophages and other proinflammatory mediators. Lungs of Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice at P7 contained large numbers of intra-alveolar macrophages, admixed with apoptotic cellular debris. Similarly, macrophages, neutrophils, and associated proinflammatory mediators are a constant feature in BPD.5 This BPD-associated inflammatory response, attributed to antenatal chorioamnionitis and intrauterine cytokine expression, as well as postnatal lung injury caused by resuscitation, oxygen toxicity, volutrauma, barotraumas, and infection, has been implicated in inhibition of alveolarization in the lungs of preterm infants.71,72

Our view of BPD may need to be integrated with the angiocentric paradigm emphasized in the current literature.73 We and others have shown that, in addition to impaired alveolar development, there is also a disruption of pulmonary microvascular development in infants with BPD5,6,74 or in BPD-like animal models such as chronically ventilated premature baboons.75,76 Although there is controversy whether angiogenesis is increased6 or decreased,73 there is general agreement that the microvasculature is dysmorphic in BPD.5,6,73,74 In the present study, the pulmonary vessel density was significantly lower in Dox-treated double-transgenic mice compared with single-transgenic littermates, similar to the microvascular anomalies seen in infants with BPD.

Several observations require special consideration. First, the clearance mechanisms for apoptotic alveolar type II cells and apoptotic Clara cells were found to be strikingly different. Alveolar type II cell apoptosis resulted in massive detachment of these cells from the alveolar wall and subsequent phagocytosis by intra-alveolar macrophages. The vast majority of apoptotic Clara cells, in contrast, remained attached to the bronchial epithelial wall or underwent phagocytosis by adjacent bronchial epithelial cells. The exact mechanisms underlying differential clearance mechanisms in various apoptotic respiratory epithelial cells remain unclear, but are likely related to the nature and extent of lateral cell-cell interactions.

Second, the apoptotic effects of FasL overexpression were virtually limited to alveolar type II cells and bronchial epithelial Clara cells. FasL up-regulation in Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL+ mice did not induce noticeable apoptosis in non-Clara bronchial epithelial cells, interstitial stromal cells, fibroblasts, or endothelial cells. The resistance of non-Clara bronchial epithelial cells to FasL activation was particularly striking because bronchial epithelial cells strongly express Fas receptor.10,11,77,78,79 The refractoriness of airway epithelial cells to Fas-induced apoptosis has been reported previously62 and has been ascribed to the expression of prosurvival proteins such as the caspase inhibitors c-IAP1 and c-IAP-2.80,81

Use of a tetracycline-regulated bitransgenic expression system in vivo requires rigorous controls to ensure accurate interpretation of the data.82 Potentially confounding variables that may influence the outcome include integration site effects (such as insertional mutagenesis), copy number effects, the effects of Dox exposure, and potential toxicity of rtTA transgene. We successfully established five (TetOp)7-FasL transgenic lines. The number of transgene copies in these lines ranged from 2 to 30. When crossed with CCSP-rtTA animals, the up-regulation of pulmonary FasL mRNA ranged from 5-fold to more than 1000-fold. The present study was focused on a transgenic line with intermediate transgene copy numbers (20) and intermediate levels of FasL up-regulation (30-fold). All lines, however, showed similar phenotypical features ascribed to FasL overexpression (ie, increased pulmonary apoptosis and arrested alveolar development), and the severity of their phenotype correlated with the level of FasL mRNA up-regulation. The occurrence of apoptosis and alveolar disruption in all transgenic lines studied indicates that the pulmonary phenotype described in this study is a specific effect of transgene expression, and not a result of nonspecific integration or copy number effects.

The tetracycline-regulated expression system uses the tetracycline analogue, Dox, for induction of transgene expression. Two distinct Dox-related phenotypic effects were identified in the present study. As previously described by others in postnatal rats,83 we found that Dox treatment during the perinatal period had adverse effects on early postnatal somatic growth. Whether the lower body weight of Dox-treated pups was the result of indirect effects on the nursing dams or direct effects on growth of the pups remains undetermined. In accordance with previous reports,83 we further found that Dox negatively affects alveolar development, a phenomenon that has been attributed to its various nonantibiotic activities that include pan-MMP (matrix metalloproteinase) inhibition83,84 and antiangiogenic and anti-inflammatory effects.85 Importantly, this study was controlled for Dox-related effects by comparing Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ animals with Dox-treated CCSP+/FasL− littermates.

In summary, we generated a transgenic mouse that allows external control of FasL expression in the respiratory epithelium. We demonstrated that pulmonary FasL overexpression targeted to the postcanalicular stages of lung development is sufficient to induce alveolar epithelial apoptosis and arrested alveolar development, mimicking the pulmonary pathology of BPD. These results support our hypothesis that alveolar epithelial apoptosis is a pivotal event in the pathogenesis of BPD. The versatility of the novel tetracycline-inducible CCSP/FasL mouse model should facilitate the analysis of the pathogenesis and new therapeutic approaches for BPD and other perinatal or adult pulmonary diseases characterized by dysregulated alveolar epithelial apoptosis. Furthermore, (TetOp)7-FasL transgenic mice, cross-bred with mice carrying the appropriate cell-specific rtTA or tTA construct, may be invaluable models to study the effects of Fas-mediated apoptosis in a wide range of conditions and organ systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Terry Pasquariello for assistance with immunohistochemical analyses, and Dr. J. F. Padbury and Dr. K. Boekelheide for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Monique E. De Paepe, M.D., Women and Infants Hospital, Dept. of Pathology, 101 Dudley St., Providence, RI 02905. E-mail: mdepaepe@wihri.org.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant P20-RR18728 to M.E.D.P.).

References

- Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, Stoll BJ, Verter J, Temprosa M, Wright LL, Ehrenkranz RA, Fanaroff AA, Stark A, Carlo W, Tyson JE, Donovan EF, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK. Very low birth weight outcomes of the National Institute of Child health and human development neonatal research network, January 1995 through December 1996 NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain AN, Siddiqui NH, Stocker JT. Pathology of arrested acinar development in postsurfactant bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:710–717. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe AJ. The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:641–643. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coalson JJ. Pathology of chronic lung disease in early infancy. Bland RD, Coalson JJ, editors. New York: M. Dekker,; Chronic Lung Disease in Early Infancy. 2000:pp 85–124. [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Powell J, Rubin SE, DeKoninck P, Appel N, Dixon M, Gundogan F. Growth of pulmonary microvasculature in ventilated preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:204–211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-927OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northway WH, Jr, Rosan RC, Porter DY. Pulmonary disease following respirator therapy of hyaline-membrane disease. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196702162760701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palta M, Gabbert D, Weinstein MR, Peters ME. Multivariate assessment of traditional risk factors for chronic lung disease in very low birth weight neonates. The Newborn Lung Project. J Pediatr. 1991;119:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe AH. Antenatal factors and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Embree-Ku M, Rubin LP, Luks FI. Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis in perinatal murine lungs. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:L730–L742. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00120.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Rubin LP, Jude C, Lesieur-Brooks AM, Mills DR, Luks FI. Fas ligand expression coincides with alveolar cell apoptosis in late-gestation fetal lung development. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:L967–L976. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Sardesai MP, Johnson BD, Lesieur-Brooks AM, Papadakis K, Luks FI. The role of apoptosis in normal and accelerated lung development in fetal rabbits. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresch MJ, Christian C, Wu F, Hussain N. Ontogeny of apoptosis during lung development. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:426–431. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199803000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schittny JC, Djonov V, Fine A, Burri PH. Programmed cell death contributes to postnatal lung development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18:786–793. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.6.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargitai B, Szabo V, Hajdu J, Harmath A, Pataki M, Farid P, Papp Z, Szende B. Apoptosis in various organs of preterm infants: histopathologic study of lung, kidney, liver, and brain of ventilated infants. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:110–114. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200107000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukkarinen HP, Laine J, Kaapa PO. Lung epithelial cells undergo apoptosis in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:254–259. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000047522.71355.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May M, Strobel P, Preisshofen T, Seidenspinner S, Marx A, Speer CP. Apoptosis and proliferation in lungs of ventilated and oxygen-treated preterm infants. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:113–121. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00038403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:29–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Wang RX, Zhang LY, Yin DL, Luo XY, Solomon JC, Jiang RF, Markos K, Davidson W, Scott DW, Shi YF. Death the Fas way: regulation and pathophysiology of CD95 and its ligand. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88:333–347. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak H, Krammer PH. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and the TRAIL (APO-2L) apoptosis systems. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:58–66. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajant H. The Fas signaling pathway: more than a paradigm. Science. 2002;296:1635–1636. doi: 10.1126/science.1071553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Chao Y, Powell JL, Rubin LP, Sharma S. Hyperoxia-induced apoptosis and Fas/FasL expression in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:L647–L659. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00445.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertine KH, Soulier MF, Wang Z, Ishizaka A, Hashimoto S, Zimmerman GA, Matthay MA, Ware LB. Fas and fas ligand are up-regulated in pulmonary edema fluid and lung tissue of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1783–1796. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64455-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagimoto N, Kuwano K, Miyazaki H, Kunitake R, Fujita M, Kawasaki M, Kaneko Y, Hara N. Induction of apoptosis and pulmonary fibrosis in mice in response to ligation of Fas antigen. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:272–278. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.3.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagimoto N, Kuwano K, Nomoto Y, Kunitake R, Hara N. Apoptosis and expression of Fas/Fas ligand mRNA in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:91–101. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.1.8998084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y, Hashimoto S, Mizuta N, Kobayashi A, Kooguchi K, Fujiwara I, Nakajima H. Fas/FasL-dependent apoptosis of alveolar cells after lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:762–769. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2003065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano K, Kawasaki M, Maeyama T, Hagimoto N, Nakamura N, Shirakawa K, Hara N. Soluble form of fas and fas ligand in BAL fluid from patients with pulmonary fibrosis and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 2000;118:451–458. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano K, Kunitake R, Maeyama T, Hagimoto N, Kawasaki M, Matsuba T, Yoshimi M, Inoshima I, Yoshida K, Hara N. Attenuation of bleomycin-induced pneumopathy in mice by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:L316–L325. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.2.L316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Liles WC, Frevert CW, Nakamura M, Ballman K, Vathanaprida C, Kiener PA, Martin TR. Recombinant human Fas ligand induces alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis and lung injury in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:L328–L335. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Liles WC, Steinberg KP, Kiener PA, Mongovin S, Chi EY, Jonas M, Martin TR. Soluble Fas ligand induces epithelial cell apoptosis in humans with acute lung injury (ARDS). J Immunol. 1999;163:2217–2225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Liles WC, Nakamura M, Ruzinski JT, Ballman K, Wong VA, Vathanaprida C, Martin TR. Fas/Fas ligand system mediates epithelial injury, but not pulmonary host defenses, in response to inhaled bacteria. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5768–5776. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5768-5776.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto Y, Kuwano K, Hagimoto N, Kunitake R, Kawasaki M, Hara N. Apoptosis and Fas/Fas ligand mRNA expression in acute immune complex alveolitis in mice. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2351–2359. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl M, Chung CS, Lomas-Neira J, Rachel TM, Biffl WL, Cioffi WG, Ayala A. Silencing of Fas, but not caspase-8, in lung epithelial cells ameliorates pulmonary apoptosis, inflammation, and neutrophil influx after hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1545–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Muller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner A, Gossen M, Zimmermann F, Jerecic J, Ullmer C, Lubbert H, Bujard H. Doxycycline-mediated quantitative and tissue-specific control of gene expression in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10933–10938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitsett JA, Clark JC, Picard L, Tichelaar JW, Wert SE, Itoh N, Perl AK, Stahlman MT. Fibroblast growth factor 18 influences proximal programming during lung morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22743–22749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl AK, Tichelaar JW, Whitsett JA. Conditional gene expression in the respiratory epithelium of the mouse. Transgenic Res. 2002;11:21–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1013986627504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichelaar JW, Lu W, Whitsett JA. Conditional expression of fibroblast growth factor-7 in the developing and mature lung. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11858–11864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JC, Tichelaar JW, Wert SE, Itoh N, Perl AK, Stahlman MT, Whitsett JA. FGF-10 disrupts lung morphogenesis and causes pulmonary adenomas in vivo. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:L705–L715. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Ma B, Homer RJ, Zheng T, Elias JA. Use of the tetracycline-controlled transcriptional silencer (tTS) to eliminate transgene leak in inducible overexpression transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25222–25229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, Homer RJ, Ma B, Riese RJ, Jr, Chapman HA, Jr, Shapiro SD, Elias JA. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase- and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1081–1093. doi: 10.1172/JCI10458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Naltner A, Yan C. Overexpression of dominant negative retinoic acid receptor alpha causes alveolar abnormality in transgenic neonatal lungs. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3004–3011. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stripp BR, Sawaya PL, Luse DS, Wikenheiser KA, Wert SE, Huffman JA, Lattier DL, Singh G, Katyal SL, Whitsett JA. cis-Acting elements that confer lung epithelial cell expression of the CC10 gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14703–14712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Tanaka M, Brannan CI, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Suda T, Nagata S. Generalized lymphoproliferative disease in mice, caused by a point mutation in the Fas ligand. Cell. 1994;76:969–976. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amy RW, Bowes D, Burri PH, Haines J, Thurlbeck WM. Postnatal growth of the mouse lung. J Anat. 1977;124:131–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti M, Brody AR, Harrison JH. Isolation and primary culture of murine alveolar type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:309–315. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.4.8600933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice WR, Conkright JJ, Na CL, Ikegami M, Shannon JM, Weaver TE. Maintenance of the mouse type II cell phenotype in vitro. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:L256–L264. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00302.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs LG. Isolation and culture of alveolar type II cells. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:L134–L147. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.4.L134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Johnson BD, Papadakis K, Luks FI. Lung growth response after tracheal occlusion in fetal rabbits is gestational age-dependent. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:65–76. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.1.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Johnson BD, Papadakis K, Sueishi K, Luks FI. Temporal pattern of accelerated lung growth after tracheal occlusion in the fetal rabbit. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:179–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aherne WA, Dunnill MS. The estimation of whole organ volume. Aherne WA, Dunnill MS, editors. London: Edward Arnold Ltd.,; Morphometry. 1982:pp 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME. Lung growth and development. Churg AM, Myers JL, Tazelaar HD, Wright JL, editors. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers,; Thurlbeck’s Pathology of the Lung. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER, Cruz-Orive LM. Morphometric methods. Crystal RG, West JB, Weibel ER, Barnes PJ, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven,; The LungScientific Foundations. 1997:pp 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam V, Mervis CF, Maxey AM, Markham NE, Abman SH. Hyperoxia reduces bone marrow, circulating, and lung endothelial progenitor cells in the developing lung: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:L1073–L1084. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00347.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantell LL, Shaffer TH, Horowitz S, Foust R, III, Wolfson MR, Cox C, Khullar P, Zakeri Z, Lin L, Kazzaz JA, Palaia T, Scott W, Davis JM. Distinct patterns of apoptosis in the lung during liquid ventilation compared with gas ventilation. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:L31–L41. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00037.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath-Morrow SA, Stahl J. Apoptosis in neonatal murine lung exposed to hyperoxia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:150–155. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.2.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Luks FI. Expression of apoptosis-related genes after fetal tracheal occlusion in rabbits. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt S, Kuhn H, Grasenack T, Gessner C, Wirtz H. Apoptosis and necrosis induced by cyclic mechanical stretching in alveolar type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:396–402. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0136OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Esteban J, Wang Y, Cicchiello LA, Rubin LP. Cyclic mechanical stretch inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in fetal rat lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:L448–L456. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00399.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards YS, Sutherland LM, Power JH, Nicholas TE, Murray AW. Cyclic stretch induces both apoptosis and secretion in rat alveolar type II cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;448:127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Matute-Bello G, Liles WC, Hayashi S, Kajikawa O, Lin SM, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Differential response of human lung epithelial cells to fas-induced apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1949–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RJ, Shannon JM. Alveolar type II cells. Crystal RG, West JB, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven,; The Lung. 1997:pp 543–555. [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Le Cras TD, Abman S, Hirth PK, Waltenberger J, Voelkel NF. Inhibition of VEGF receptors causes lung cell apoptosis and emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1311–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI10259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuder RM, Zhen L, Cho CY, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Salvemini D, Voelkel NF, Flores SC. Oxidative stress and apoptosis interact and cause emphysema due to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor blockade. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:88–97. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0228OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey EC, Keane J, Kuang PP, Snider GL, Goldstein RH. Severity of elastase-induced emphysema is decreased in tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta receptor-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 2002;82:79–85. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Dalal SS, Chen ES, Downey R, Schulman LL, Ginsburg M, D'Armiento J. Human collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase-1) expression in the lungs of patients with emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:786–791. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Cool CD, Lynch DA, Flores SC, Voelkel NF. Endothelial cell death and decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:737–744. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2002117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CG, Kang HR, Homer RJ, Chupp G, Elias JA. Transgenic modeling of transforming growth factor-beta(1): role of apoptosis in fibrosis and alveolar remodeling. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:418–423. doi: 10.1513/pats.200602-017AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshiba K, Yokohori N, Nagai A. Alveolar wall apoptosis causes lung destruction and emphysematous changes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:555–562. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0090OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Contribution of inflammation to lung injury and development. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F132–F135. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.068544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thebaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:978–985. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1660PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt AJ, Pryhuber GS, Huyck H, Watkins RH, Metlay LA, Maniscalco WM. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor. Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1971–1980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]