Abstract

Gene targeting has two important applications. One is the inactivation of genes (“knockouts”), and the second is the correction of a mutated allele back to wild-type (“gene therapy”). Central to these processes is the efficient introduction of the targeting DNA into the cells of interest. In humans, this targeting is often accomplished through the use of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV). rAAV is presumed to use a pathway of DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair termed homologous recombination (HR) to mediate correct targeting; however, the specifics of this mechanism remain unknown. In this work, we attempted to generate Ku70-null human somatic cells by using a rAAV-based gene knockout strategy. Ku70 is the heterodimeric partner of Ku86, and together they constitute an end-binding activity that is required for a pathway [nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ)] of DSB repair that is believed to compete with HR. Our data demonstrated that Ku70 is an essential gene in human somatic cells. More importantly, however, in Ku70+/− cells, the frequency of gene targeting was 5- to 10-fold higher than in wild-type cells. RNA interference and short-hairpinned RNA strategies to deplete Ku70 phenocopied these results in wild-type cells and greatly accentuated them in Ku70+/− cell lines. Thus, Ku70 protein levels significantly influenced the frequency of rAAV-mediated gene targeting in human somatic cells. Our data suggest that gene-targeting frequencies can be significantly improved in human cells by impairing the NHEJ pathway, and we propose that Ku70 depletion can be used to facilitate both knockout and gene therapy approaches.

Keywords: gene therapy, nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV), Ku, DNA protein kinase

Somatic gene targeting is defined as the intentional modification of a genetic locus in a living cell (1). This technology has two general applications of interest and importance. One is the inactivation of genes (“knockouts”), a process in which the two wild-type alleles of a gene are sequentially inactivated to determine the loss-of-function phenotype(s) of that particular gene. The second application is the clinically more relevant process of gene therapy, which, in a strict sense, involves correcting a preexisting mutated allele of a gene back to wild-type (“knockins”) to alleviate some pathological phenotype associated with the mutation. Importantly, although these two processes are conceptually reciprocal opposites of one another, they are mechanistically identical because both require a form of DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair termed homologous recombination (HR).

In HR (2), the ends of the donor dsDNA are resected to yield 3′-ssDNA overhangs, which are targets bound by RAD51 and RAD52. RAD51 is a potent strand exchange protein, and together with RAD54 (3), an ATPase that remodels chromatin, it facilitates cross-over of the incoming donor DNA with its cognate chromosomal homologous sequences. This gene-targeting event generates a complex structure that is identical to the linearized plasmid “ends-out” recombination intermediates that have been defined in yeast (4). Resolution of this structure requires the action of helicases, polymerases, resolvases, and ligases in a complicated process that has not yet been rigorously defined (2). Importantly, human cells express all of the HR gene products needed to carry out gene targeting (1). These events occur, however, only at a low frequency because of the preferred usage of a competing pathway of DNA DSB repair, nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ).

NHEJ is an evolutionarily conserved process that joins nonhomologous DNA molecules together (5). In their seminal work on gene targeting, Thomas and Capecchi (6) showed that although somatic mammalian cells can integrate a linear duplex DNA into corresponding homologous chromosomal sequences using HR, the frequency with which recombination into nonhomologous sequences occurred via NHEJ was at least 1,000-fold greater. Although not all of the details of NHEJ have been elucidated, much is known about the process. First, the heterodimeric Ku (Ku86:Ku70) protein binds onto the ends of the donor DNA and prevents the nucleolytic degradation that would otherwise shunt the DNA into the HR pathway (see above and ref. 5). The binding of Ku to the ends of the DNA then recruits and activates the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). This DNA-protein complex is then brought into contact with a chromosome into which a DSB is introduced by a mechanism that is poorly understood, although it correlates frequently with chromosomal palindromic sequences (7). Regardless, the chromosomal ends are probably also occupied by Ku and DNA-PKcs, which facilitates the formation of a synaptic complex with the donor DNA (8). Once DNA-PKcs is properly assembled at the broken ends, it, in turn, recruits additional factors such as the nuclease, Artemis, to trim the ends and a DNA ligase complex consisting of DNA ligase IV (LIGIV)-x-ray cross-complementing group 4-XRCC-4-like factor, to seal the break(s) (5). In summary, humans are different from bacteria and lower eukaryotes in that DSB repair proceeds primarily through a NHEJ recombinational pathway. Moreover, NHEJ must be overcome to facilitate gene targeting, which can only occur when the incoming DNA is shunted into the HR pathway.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a nonpathogenic parvovirus with a natural tropism for human cells that depends on a helper virus (usually adenovirus and hence the name) for a productive infection (9). In the intervening decade since it was demonstrated that recombinant AAV (rAAV) could be used as a vector for gene targeting in human cells (10), this methodology has gained wide acceptance (1). Nineteen different genes have been modified (generally knocked out) in a plethora of immortalized and normal diploid human tissue culture lines (ref. 1 and F.J.F. and S.O., unpublished data). Moreover, human adult stem cell lines derived from osteogenesis imperfecta patients afflicted with a dominant-negative mutation in the COL1A1 gene have been corrected (a knockin) with rAAV vectors (11). Last, >20 clinical gene therapy trials using rAAV are currently in progress. There are, however, reports of potential difficulties with the clinical use of rAAV vectors. In particular, a recent report found that in a mouse model for lysosomal storage disease mucopolysaccharidosis VII, the random integration of rAAV was associated with a high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (ref. 12; for review, see ref. 13). Thus, a better understanding of the mechanism of rAAV-mediated gene targeting and the factors that influence the frequency with which it correctly targets (presumably HR-mediated) vs. those that influence its random integration (presumably NHEJ-mediated) clearly seems warranted.

Using classic gene-targeting methodologies, our laboratory has shown that the NHEJ gene Ku86 is essential in human somatic cells (14). To extend these studies to Ku70, we have used a rAAV vector approach. As expected, these experiments demonstrated that Ku70 is also essential. Surprisingly, however, the frequency of correct gene targeting increased 5- to 10-fold in Ku70-heterozygous (Ku70+/−) cells. RNA interference and short-hairpinned RNA strategies to deplete Ku70 phenocopied these results in wild-type cells and greatly accentuated them in Ku70+/− cell lines. To support the generality of these findings, we extended them to an additional two loci, the chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 (CCR5) gene and LIGIV and observed similar effects. Thus, Ku70 protein levels influenced the frequency of correct rAAV-mediated gene targeting in human somatic cells. Our data demonstrate that gene-targeting frequencies can be significantly improved by impairing the NHEJ pathway, and we propose that Ku70 depletion can be used to facilitate both knockout and gene therapy approaches.

Results

Use of Gene Targeting to Generate Ku70-Null HCT116 Cells.

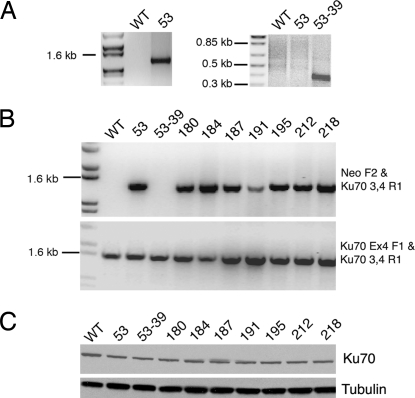

Using rAAV-based methodology, we have generated a Ku70+/− HCT116 cell line (ref. 15 and Fig. 1B). HCT116 is a human colon carcinoma cell line that is diploid, has a stable karyotype, and is wild type for almost all of the DNA DSB repair, checkpoint, and chromosome stability genes that have been examined (ref. 1 and Fig. 1A). Ku70+/− HCT116 cells showed haploinsufficient deficits as they grew slower, were more sensitive to ionizing radiation, and had shortened telomeres compared with the parental cell line (15). These phenotypes were not unexpected because heterozygous Ku86 (Ku86+/−) HCT116 cells had similar haploinsufficiencies (14, 16). Because we had also subsequently shown that human Ku86-null (Ku86−/−) cell lines were not viable, we wanted to extend this observation to human Ku70-deficient cells. To achieve this goal experimentally, one of the Ku70+/− clones (clone 53; Figs. 1B and 2A) was transiently exposed to Cre recombinase. Cre should excise the internal neomycin selection cassette, which is flanked by loxP sites, within the integrated targeting vector (Fig. 1B). Forty-eight single cell clones were picked, duplicated into medium containing or lacking G418, and G418-sensitive clones were identified. Correct excision of the neomycin gene was confirmed by the generation of a diagnostic ≈350-bp PCR product with the primer set 70 Cre F and 70 Cre R (Figs. 1C and 2A, 53-39 lane). Seven such clones were obtained in this fashion, and one of them, clone 53-39, was used for a second round of gene targeting with the original targeting vector containing the neomycin selection cassette. Productive infection of clone 53-39 cells should produce three potential outcomes: (i) random targeting (the majority of the events); (ii) correct targeting, but of the already inactivated allele from the first round of targeting (i.e., “retargeting”; Fig. 1D); or (iii) correct targeting of the remaining functional allele to generate the desired null clone (Fig. 1E). Several diagnostic PCR strategies were used to distinguish these events (Fig. 1). In two separate screens (elaborated in detail below) a total of 27 correctly targeted clones were obtained. Strikingly, all 27 clones were retargeted. This conclusion was substantiated by the fact that although all of the clones were correctly targeted (Figs. 1D and 2B Upper, and data not shown), they still retained exon 4 sequences (Fig. 2B Lower and data not shown). Moreover, all 27 of the clones still expressed Ku70 protein at levels that were ≈50% of that observed in the parental cell line (Fig. 2C and data not shown). The large disequilibrium in gene targeting in which 27 of 27 clones were retargeted and no null clones were obtained strongly suggests that Ku70, like Ku86, is an essential gene in human somatic cells.

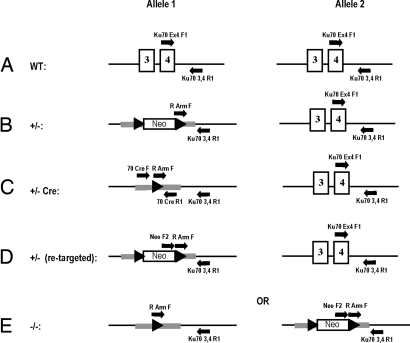

Fig. 1.

Experimental strategy and screening protocols for disruption of the Ku70 locus in human somatic cells. (A) Diagrams of the relevant portion (large rectangles: exons 3 and 4) of the human Ku70 genomic locus (horizontal line: genomic DNA) in the parental wild-type cells. The black arrows demarcate the indicated PCR primers. (B) Ku70 locus in Ku70+/− (clone 53) cells. One of the endogenous alleles has been replaced by a homologous genomic sequence (horizontal gray bars), LoxP sites (filled triangles), and the neomycin (Neo) resistance gene (rectangle). Additional PCR primers (black arrows) are indicated. (C) Ku70 locus in Ku70+/− (clone 53-39) cells after Cre treatment. All symbols are as in B. Additional PCR primers (black arrows) are also indicated. (D) Ku70 locus in Ku70+/− (clone 53-39) cells after retargeting to the already inactive allele. All symbols are as in B. Additional PCR primers (black arrows) are also indicated. (E) Ku70 locus in Ku70+/− (clone 53-39) cells after correct second-round targeting to the functional allele to generate the null cell line. All symbols are as in B.

Fig. 2.

Disruption of the Ku70 locus in HCT116 cells by gene targeting. (A) PCR characterization of the Ku70+/− clones 53 and 53-39. Ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained agarose gels are shown. (Left) From left to right the lanes are: molecular weight markers, genomic DNA isolated from wild-type (WT) cells, and genomic DNA derived from clone 53 cells. The PCR used the primers RArmF and Ku70 3,4 R1 (Fig. 1), and the diagnostic ≈1.3-kb band was observed only in clone 53. (Right) From left to right the lanes are: molecular weight markers, genomic DNA isolated from clone 53 cells, and genomic DNA derived from clone 53-39 cells. The PCR used the primer set 70 Cre F and 70 Cre R, and the diagnostic ≈350-bp PCR product was observed only in clone 53-39. (B) Identification of correctly targeted clones after the second round of gene targeting. EtBr-stained agarose gels are shown. From left to right the lanes are: molecular weight markers and then genomic DNA isolated from the indicated cell lines. (Upper) The PCR used the primer set Neo F2 and Ku70 3,4 R1 (Fig. 1), and the diagnostic ≈1.3-kb band was observed only in those clones that were correctly targeted and contained the Neo gene. (Lower) The PCR used the primer set Ku70 Ex4 F1 and Ku70 3,4 R1 (Fig. 1), and the diagnostic ≈1.3-kb band, which indicated the retention of at least one copy of exon 4, was observed in all of the clones. (C) All correctly targeted clones still express Ku70 protein, albeit at reduced levels. Whole-cell extract of the indicated cell lines was subjected to immunoblot analyses to detect Ku70 (Upper), and tubulin (Lower) protein levels.

Diminished Ku70 Protein Levels Increase the Gene-Targeting Frequency of the Ku70 Locus in HCT116 Cells.

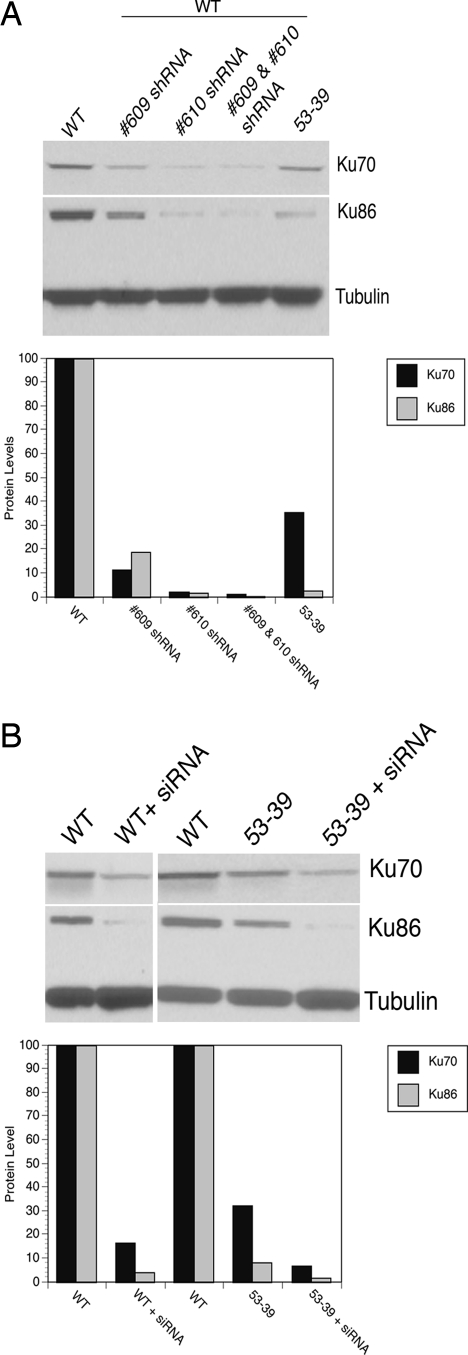

The above results, although important, were rather expected. One surprising finding, however, was observed. Our initial frequency for obtaining Ku70+/− cell lines was 0.69%, 3 correctly targeted clones identified from 437 G418-resistant, internal control PCR-positive clones screened (ref. 15 and Table 1). In the first attempt to obtain a null clone, 4 correctly targeted clones (all retargeted) were identified from a total of 97 G418-resistant colonies for a targeting frequency of 4.12% (Table 1). This represented a 6-fold (4.12/0.69 = 5.97) increase in the gene-targeting frequency in Ku70+/− cells. To investigate whether the reduced Ku70 expression level was facilitating a higher frequency of correct targeting, we attempted to phenocopy this effect. Thus, the parental HCT116 cell line (Ku70+/+) was used to stably express a short hairpin RNA (shRNA), obtained from the MISSION TRC-Hs 1.0 (human) lentiviral shRNA library (17), targeting Ku70. Five different shRNA sequences (608, 609, 610, 611, and 612) were tested for their ability to knock down the level of Ku70 in HCT116 cells. Among these five sequences, 609 and 610 reduced Ku70 expression the best, to ≈10% of that observed in the parental line (Fig. 3A). The cell line expressing the shRNA sequence 610 (Ku70shRNA) was used for Ku70 gene targeting, and 2 of 65 total clones were correctly targeted (Table 1). This represented a 4.6-fold increase over the parental HCT116 line. Next, we used the siGENOME SMARTPool on the parental HCT116 cells to silence Ku70 expression to ≈20% of that observed in the control transfected population (Fig. 3B). These cells (Ku70siRNA) had an 8.4-fold increase in gene targeting (10 of 173; 5.78%; Table 1). To extend this line of experimentation to its logical conclusion, siRNA was used in an attempt to further knock down Ku70 protein expression in 53-39 Ku70+/− cells that already contained reduced levels of Ku70 because of genetic ablation. Thus, 53-39 Ku70+/− cells were transfected twice at 24-h intervals with the siGENOME SMARTPool for Ku70. A significant reduction in Ku70 protein levels as assessed by Western blot analysis 48 h after the first siRNA treatment was observed (Fig. 3B, 53-39 + siRNA). 53-39 Ku70siRNA cells expressed ≈5% of the Ku70 protein compared with the parental cells. Moreover, the Ku86 protein level in 53-39 Ku70siRNA cells was also decreased, confirming previous observations suggesting that the stabilities of Ku70 and Ku86 are coordinately linked (5, 14). Impressively, 23 correctly targeted (all retargeted) clones were recovered from 111 G418-resistant clones screened, for a targeting frequency of 20.72% (Table 1). This represented a 30-fold increase in gene targeting compared with the parental line. It is important to note that this was a minimum frequency because a statistically equal number (i.e., 23) of null clones were presumably not recovered because Ku70 is essential. In toto, these results demonstrated that lowering the expression level of Ku70 significantly increased the gene-targeting frequency at the Ku70 locus in HCT116 cells.

Table 1.

Summary of gene-targeting frequencies at the Ku70 locus

| Cell line | No. of colonies screened* | No. of correctly targeted clones† | Targeting frequency‡ | Fold increase§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT HCT116 | 437 | 3 | 0.69 | 1.0 |

| WT HCT116 + Ku70 siRNA | 173 | 10 | 5.78 | 8.4 |

| WT HCT116 + Ku70 shRNA | 65 | 2 | 3.08 | 4.4 |

| 53-39 (Ku70+/−) | 97 | 4 | 4.12 | 6.0 |

| 53-39 (Ku70+/−) + Ku70 siRNA | 111 | 23 | 20.72 | 30.0 |

*Drug-resistant clones that were also positive for the internal control PCR.

†Drug-resistant clones that showed correct targeting by PCR.

‡Targeting frequency is the number of correctly targeted colonies per 100 drug-resistant colonies screened.

§The WT targeting frequency is set at 1. The fold increase is the targeting frequency in a specific cell line divided by the targeting frequency in the WT background (0.69).

Fig. 3.

Disruption of Ku70 gene expression by RNA interference technologies. (A) Stable cell lines generated using shRNA expression show reduced expression of Ku. Wild-type HCT116 cells were infected with lentiviruses carrying short-hairpin sequences (609, 610, or both 609 and 610). Whole-cell extracts from stable puromycin-resistant clones were subjected to immunoblot analyses using extracts from wild-type (WT) and clone 53-39 as controls. The extracts were probed sequentially for Ku70 expression and then Ku86 and tubulin. For the gene-targeting experiments described in the text, the 610 shRNA-treated stable line was used. A PhosphorImager quantitation of this blot is shown below the figure. (B) Transient depletion of Ku70 protein expression. Wild-type and Ku70+/− 53-39 cells were transfected with a Ku70 siGENOME SMARTpool. All cells were transfected twice at 24-h intervals and then harvested 72 h after the first siRNA treatment. A knockdown of gene expression was measured by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. A PhosphorImager quantitation of this blot is shown below the figure.

Diminished Ku70 Protein Levels Increase the Gene-Targeting Frequency at Other Loci in HCT116 Cells.

To investigate the generality of the enhancement of gene targeting by Ku70 depletion, the gene-targeting frequency at another locus, chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 (CCR5), was determined. CCR5 is a cell surface coreceptor for the human immune deficiency virus and has no known role in DNA repair (18). Moreover, a rAAV targeting vector for CCR5 and methodologies for identifying correct targeting events had already been well established by the laboratory of Bert Vogelstein (19). Using this vector and these methodologies, we determined that the targeting frequency for the parental cell line was 1.06% (Table 2). In four independent Ku70-reduced backgrounds, we observed a significant increase in the correct gene-targeting frequency (Table 2), which included Ku70shRNA cells (5.2%; a 4.5-fold increase), Ku70siRNA cells (5.3%; a 4.6-fold increase), 53-39 (Ku70+/−) cells (6.6%; a 5.8-fold increase) and 53-39siRNA cells (9.9%; a 8.6-fold increase). Thus, without exception and regardless of which technique was used, a reduction of Ku70 expression increased the frequency of gene targeting 4- to 9-fold at the CCR5 locus.

Table 2.

Summary of gene-targeting frequencies at the CCR5 locus

| Cell line | No. of colonies screened* | No. of correctly targeted clones† | Targeting frequency‡ | Fold increase§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT HCT116 | 262 | 3 | 1.15 | 1.0 |

| WT HCT116 + Ku70 siRNA | 150 | 8 | 5.33 | 4.6 |

| WT HCT116 + Ku70 shRNA | 96 | 5 | 5.20 | 4.5 |

| 53-39 (Ku70+/−) | 105 | 7 | 6.66 | 5.8 |

| 53-39 (Ku70+/−) + Ku70 siRNA | 152 | 15 | 9.86 | 8.6 |

*Drug-resistant clones that were also positive for the internal control PCR.

†Drug-resistant clones that showed correct targeting by PCR.

‡Targeting frequency is the number of correctly targeted colonies per 100 drug-resistant colonies screened.

§The WT targeting frequency is set at 1. The fold increase is the targeting frequency in a specific cell line divided by the targeting frequency in the WT background (1.15).

Finally, the effect of Ku70 depletion on gene-targeting frequency at the LIGIV locus was analyzed. Recently, using a rAAV-mediated knockout approach (S.O. and E.A.H., unpublished results), we generated LigIV+/− cell lines in a HCT116 background by deleting part of exon 3 of this locus. Two correctly targeted LIGIV cell lines were identified from 176 drug-resistant clones screens, for a targeting frequency of 1.13% (Table 3). When these studies were repeated in the Ku70+/− clone 53-39, 6 correctly targeted LIGIV cell lines from 148 drug-resistant clones were identified. This corresponds to a 4.05% targeting frequency and a 3.6-fold increase in gene targeting compared with the parental line.

Table 3.

Summary of gene-targeting frequencies at the LIGIV locus

| Cell line | No. of colonies screened* | No. of correctly targeted clones† | Targeting frequency‡ | Fold increase§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT HCT116 | 176 | 2 | 1.13 | 1.0 |

| 53-39 (Ku70+/−) | 148 | 6 | 4.05 | 3.5 |

*Drug-resistant clones that were also positive for the internal control PCR.

†Drug-resistant clones that showed correct targeting by PCR.

‡Targeting frequency is the number of correctly targeted colonies per 100 drug-resistant colonies screened.

§The WT targeting frequency is set at 1. The fold increase is the targeting frequency in a specific cell line divided by the targeting frequency in the WT background (1.13).

In summary, multiple targeting experiments at three different loci (Ku70, CCR5, and LIGIV) demonstrated that a reduction in Ku70 expression facilitates correct gene targeting in human somatic cells.

Diminished Ku70 Protein Levels Do Not Decrease the Frequency of rAAV Random Integration.

An explanation of the above results is that in the presence of reduced levels of Ku70, the number of correct gene-targeting events increases. An alternative possibility is that the absolute number of correct targeting events remains constant but that the number of random integration events is decreased. To test this latter possibility experimentally, the frequency of random integration events was measured. Equal numbers of the parental cells (WT HCT116), parental cells expressing shRNA (WT + shRNA), Ku70+/− cells (53-39), and Ku70+/− cells expressing shRNA (53-39 + shRNA) were independently infected with three different concentrations of two different rAAV viral stocks. Two to three weeks later, the total number of drug-resistant colonies was scored. There was no statistically significant difference between any of the cell lines for either virus at any concentration [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Thus, we conclude that a reduction in Ku70 in human somatic cells does not result in a reduction of random integration of rAAV gene-targeting vectors.

Discussion

Ku70 Is Essential in Human Somatic Cells.

The Ku heterodimer is a well conserved protein(s), with homologs known to exist in every species from bacteria to humans (5). In all organisms examined, mutations in either Ku subunit result in the expected deficits in DNA DSB repair, DNA recombination, and sensitivities to DNA-damaging agents. Importantly, in all organisms, with one glaring exception, Ku is nonetheless dispensable for viability. Intriguingly, humans appear to be unique in that Ku has evolved into an essential gene. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of documentation for even a single patient with a mutation in either Ku subunit. Moreover, the targeted disruption of both alleles of the Ku86 gene in human HCT116 somatic cells was lethal (14). The reason that Ku should be uniquely essential in humans is not clear, although a role in telomere maintenance seems likely (16). Here, we corroborate the hypothesis that Ku is essential in humans by demonstrating that Ku70-null cells are not viable. This conclusion was based on 27 recovered second-round targeting events, which occurred solely on the already inactive allele (Fig. 2 and Table 1). There is overwhelming evidence to support the view that targeting vectors target the paternal and maternal alleles without bias. In an experiment designed to disrupt β-catenin, 11 second-round targeting events occurred on the functional allele and 15 on the inactive allele (20). Similarly, in two independent studies involving Ki-ras, 4 of 7 (21) and 9 of 15 (22) targeting events occurred on the functional allele. Moreover, in rAAV-mediated targeting studies, 10 of 19 targeting events for COL1A1 occurred on the wild-type allele and 9 of 19 on the mutant allele (11). Because of this lack of bias in the targeting methodology, the striking disequilibrium of 27 of 27 retargeting events is strong evidence for the essential nature of Ku70 in HCT116 cells. A direct demonstration of the essential nature of Ku70 awaits the construction of a cell line expressing a conditionally null Ku70 allele.

Reduced Ku70 Expression Augments the Frequency of Correct Gene Targeting in Human Somatic Cells.

Attempts to target the second allele of the Ku70 locus demonstrated that the gene-targeting frequency was higher in Ku70+/− cells compared with the parental cell line. The interpretation of this result, that a reduction in Ku protein levels increases the frequency of gene targeting, was confirmed by two independent methodologies: that of transient RNA interference and the stable use of short-hairpinned RNAs (Table 1) and was confirmed at additional loci (Tables 2 and 3). It should be noted, however, that there was not always a linear relationship between the levels of Ku70 protein in a cell line and the frequency of gene targeting. Thus, the Ku70shRNA cells expressed less Ku70 protein than the Ku70+/− cells but had a lower, and not the predicted higher, frequency of gene targeting (Tables 1 and 2). This was probably caused by the much slower growth of the Ku70shRNA cells (F.J.F., unpublished observations), which may have a deleterious effect on gene targeting because rAAV preferentially transduces actively dividing cells (23). Similarly, the Ku70siRNA cells expressed less Ku70 protein than the Ku70+/− cells, but the two cell lines often had about the same frequency of gene targeting (Tables 1 and 2). This was likely because the Ku70siRNA cells represented a heterogeneous population of cells with some cells being effectively transfected and other cells not, which presumably translated itself into heterogeneous targeting frequencies. These technical qualifiers notwithstanding, a reduction in Ku70 protein expression was without exception always associated with an increase in the frequency of correct gene targeting.

The demonstration that Ku can regulate gene targeting is very well documented in fungal systems. Thus, deletion of Neurospora crassa Ku70 and Ku86 genes resulted in higher gene-targeting frequencies (100% in the mutants compared with 20% in wild-type cells) (24). This observation was then used in a robotics-driven, whole-genome approach to expedite the functional inactivation of 103 transcription factor genes (25) demonstrating the potent utility of Ku-reduced strains. Moreover, there has been a spate of reports of highly efficient correct gene targeting in Ku-deletion strains of five different species of Aspergillus [e.g., Aspergillus niger (26)], and Sordaria macrospora (27), and Cryptococcus neoformans (28), demonstrating that Ku-deficient strains are useful for gene targeting in filamentous fungi. Furthermore, the disruption of yKU70 (29) or KlKU80 (30) also increased the frequency of gene targeting in the budding yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis, respectively. Thus, in fungi, where Ku is not essential, there is an exceptionally good correlation between reduced Ku expression and increased gene targeting.

An extrapolation of these observations to higher eukaryotes, however, has been lacking. Thus, deletion of Ku70 in chicken DT40 cells (31) and Ku70 (32) or Ku86 (33) in mouse cells did not result in an increase in gene-targeting frequencies. The discrepancy between human and chicken somatic cells can be reconciled given that DT40 cells are known to employ HR at high frequency (34). An explanation for the difference between human and mouse cells, however, is less obvious, albeit consistent with the more stringent requirement for Ku/NHEJ in human cells (this work and ref. 14). One possibility may be that mouse embryonic stem or fibroblast cells, the cells in which the mouse targeting experiments were carried out, may, like DT40 cells, carry out HR at a higher frequency than human somatic cells. Another possibility is that there are locus-specific effects as, to date, only a single X-linked locus (the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase locus) has been examined in the mouse (32, 33). In summary, additional experiments are needed before it can be determined whether or not the observations reported here for human somatic cells are evolutionarily conserved.

There are multiple indirect mechanisms whereby Ku could regulate gene targeting such as by modulating the conversion of viral ssDNA into dsDNA. This process would be required if the gene replacement aspect of rAAV gene targeting requires two independent cross-over events (and thus two independent 3′ ends on the donor DNA). Hendrie and Russell, however, have argued (albeit circumstantially) that rAAV-mediated gene targeting is more likely mediated by viral ssDNA rather than dsDNA (35). If this hypothesis is true, then we would instead favor a direct “competition” model that has been suggested by many laboratories (e.g., ref. 36) whereby Ku and Rad52 compete for the viral DNA ends and shunt the virus into either NHEJ or HR pathways, respectively. This model is consistent with the demonstration that both Ku and Rad52 physically bind to rAAV inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) during a viral infection (37). In this model, a reduction in Ku posits that Rad52 will statistically stand a better chance of binding the hairpin-shaped viral ITRs and funnel the DNA into the HR pathway. In a wild-type cell, however, where Ku is more abundant than Rad52, the presence of normal amounts of Ku would favor random integration mediated by NHEJ. Mechanistically, the most likely role for Ku in rAAV random integration is to recruit DNA-PKcs to the viral ITRs. DNA-PKcs, would, in turn, recruit and activate the nuclease Artemis, which nicks open the viral ITR hairpins (38), facilitating integration of the virus. The observation that the vast majority of random rAAV integration events that have been sequenced have a viral end point that maps to the viral ITRs supports this interpretation (39). The competition model is not consistent with the conclusion that DNA-PK actually inhibits rAAV integration in mouse muscle (40) nor with a report that shRNA-mediated silencing of DNA-PKcs gene expression in human MO59K somatic cells had no effect on rAAV-mediated gene targeting (41). However, in preliminary studies with HCT116 cell lines containing functional inactivation of either one or both DNA-PKcs alleles, we have repeatedly seen large increases in the correct gene-targeting frequency that are comparable to those reported here for Ku-reduced cell lines (unpublished data) supporting both a role for DNA-PKcs in viral ITR nicking (38) and the competition model.

Other investigators have suggested that in addition to Ku and Rad52 competing for DNA ends, Ku may also actively suppress HR (42). We favor this hypothesis because it provides at least a partial explanation for the finding that the frequency of random integrations was not lower in a Ku-reduced background (Fig. S1). Thus, if HR not only has less competition for the viral ends in the absence of Ku but is also more active, it may facilitate viral integrations at chromosomal sites that are quasi-homologous to the viral ITRs. Another potential explanation for the lack of an effect of a Ku deficiency on overall integrations is the recent description of an alternative (Ku-independent) NHEJ pathway (A-NHEJ; reviewed in ref. 43). In contrast to the classical, Ku-dependent NHEJ, which works on virtually all DNA DSBs, A-NHEJ seems to only work on a subset of these and/or in specialized pathways because it can participate in the repair of switch recombination-induced DSBs but not ionizing radiation-induced DSBs (43). If A-NHEJ can also work in the pathway of gene targeting to facilitate random integrations, it might explain why the frequency of correct gene targeting goes up (Tables 1–3) even when the frequency of random targeting does not change (Fig. S1). In any case, it is important to emphasize that it has long been known that additional pathways for chromosomal DNA integration are quite active in DNA-PK-defective cells (44).

Regardless of the precise mechanism by which Ku regulates rAAV integration, we have demonstrated that a reduction in the levels of Ku70 in HCT116 human somatic cells greatly elevates the frequency of correct gene targeting. These observations have significant practical implications for basic researchers interested in gene-disruption strategies and for clinical researchers interested in gene therapy.

Methods

Cell Culture.

The human colon cancer cell line HCT116 was obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in McCoy's 5A medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 units/ml streptomycin. The cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cell lines harboring the targeting vector were grown in 1 mg/ml G418.

Silencing of Ku70.

The pLKO.1-puromycin-based lentiviral vectors containing sequence-verified shRNA targeting Ku70 (XRCC6; GenBank accession number NM_001469) were obtained from the MISSION TRC-Hs 1.0 (Human) shRNA library through Sigma–Aldrich [TRCN0000039608 (608), TRCN0000039609 (609), TRCN0000039610 (610), TRCN0000039611 (611), TRCN0000039612 (612)]. For the RNAi experiments, predesigned, double-stranded siRNAs (SMARTPool) targeting human Ku70 were purchased from Dharmacon.

Targeting Vector Construction, Packaging, and Infection.

The targeting vectors, Ku70-Neo and LIGIV-Neo, were constructed by using the rAAV system as described elsewhere (ref. 15 and S. O., unpublished data). The CCR5-Neo targeting vector has been described in ref. 19. All virus packaging and infections were performed as described in ref. 19.

Isolation of Genomic DNA and Genomic PCR.

Genomic DNA for PCR screening was isolated by using phenol extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. Ku70- and LIGIV-targeting events were identified by PCR using the conditions described elsewhere (19). CCR5-targeting events were identified by PCR using the primers and conditions described in ref. 19.

Antibodies and Immunoblotting.

Ku70 and Ku86 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and α-tubulin (Covance) antibodies were used for detection. Proteins were subjected to electrophoresis on a 4–20% gradient gel (Bio-Rad), electroblotted, and detected as described in ref. 15.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are indebted to Dr. Bruce Vogelstein (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and the many members of his laboratory who were extremely generous with their reagents and advice. We also thank Brian Ruis (University of Minnesota) for technical help in establishing and using the rAAV gene-targeting system. We thank Dr. A.-K. Bielinsky for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants GM 069576 and HL079559 (to E.A.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0712060105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hendrickson EA. Gene targeting in human somatic cells. In: Conn PM, editor. Sourcebook of Models for Biomedical Research. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 2008. pp. 509–525. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Veelen L, Wesoly J, Kanaar R. Biochemical and cellular aspects of homologous recombination. In: Seide W, Kow YW, Doetsch P, editors. DNA Damage Recognition. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2006. pp. 581–607. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyer WD, Li X, Rolfsmeier M, Zhang XP. Rad54: the Swiss Army knife of homologous recombination? Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4115–4125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastings PJ, McGill C, Shafer B, Strathern JN. Ends-in vs. ends-out recombination in yeast. Genetics. 1993;135:973–980. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.4.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrickson EA, Huffman JL, Tainer JA. Structural aspects of Ku and the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex. In: Seide W, Kow YW, Doetsch P, editors. DNA Damage Recognition. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2006. pp. 629–684. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell. 1987;51:503–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inagaki K, et al. DNA palindromes with a modest arm length of greater, similar 20 base pairs are a significant target for recombinant adeno-associated virus vector integration in the liver, muscles, and heart in mice. J Virol. 2007;81:11290–11303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00963-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spagnolo L, Rivera-Calzada A, Pearl LH, Llorca O. Three-dimensional structure of the human DNA-PKcs/Ku70/Ku80 complex assembled on DNA and its implications for DNA DSB repair. Mol Cell. 2006;22:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter BJ. Adeno-associated virus and the development of adeno-associated virus vectors: A historical perspective. Mol Ther. 2004;10:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell DW, Hirata RK. Human gene targeting by viral vectors. Nat Genet. 1998;18:325–330. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain JR, et al. Gene targeting in stem cells from individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta. Science. 2004;303:1198–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1088757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donsante A, et al. AAV vector integration sites in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2007;317:477. doi: 10.1126/science.1142658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell DW. AAV vectors, insertional mutagenesis, and cancer. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1740–1743. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li G, Nelsen C, Hendrickson EA. Ku86 is essential in human somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:832–837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022649699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fattah KR, Ruis BL, Hendrickson EA. Mutations to Ku reveal differences in human somatic cell lines. DNA Repair. 2008;7:762–774. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myung K, et al. Regulation of telomere length and suppression of genomic instability in human somatic cells by Ku86. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5050–5059. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.5050-5059.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffat J, et al. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lederman MM, Penn-Nicholson A, Cho M, Mosier D. Biology of CCR5 and its role in HIV infection and treatment. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296:815–826. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli M, Rago C, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Facile methods for generating human somatic cell gene knockouts using recombinant adeno-associated viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JS, et al. Oncogenic β-catenin is required for bone morphogenetic protein 4 expression in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2744–2748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirasawa S, Furuse M, Yokoyama N, Sasazuki T. Altered growth of human colon cancer cell lines disrupted at activated Ki-ras. Science. 1993;260:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.8465203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JS, Lee C, Foxworth A, Waldman T. B-Raf is dispensable for K-Ras-mediated oncogenesis in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1932–1937. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell DW, Miller AD, Alexander IE. Adeno-associated virus vectors preferentially transduce cells in S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8915–8919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ninomiya Y, Suzuki K, Ishii C, Inoue H. Highly efficient gene replacements in Neurospora strains deficient for nonhomologous end-joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12248–12253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402780101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colot HV, et al. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10352–10357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer V, et al. Highly efficient gene targeting in the Aspergillus niger kusA mutant. J Biotechnol. 2007;128:770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poggeler S, Kuck U. Highly efficient generation of signal transduction knockout mutants using a fungal strain deficient in the mammalian Ku70 ortholog. Gene. 2006;378:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goins CL, Gerik KJ, Lodge JK. Improvements to gene deletion in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans: Absence of Ku proteins increases homologous recombination, and cotransformation of independent DNA molecules allows rapid complementation of deletion phenotypes. Fungal Genet Biol. 2006;43:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamana Y, et al. Regulation of homologous integration in yeast by the DNA repair proteins Ku70 and RecQ. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;273:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-1108-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kooistra R, Hooykaas PJ, Steensma HY. Efficient gene targeting in Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast. 2004;21:781–792. doi: 10.1002/yea.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukushima T, et al. Genetic analysis of the DNA-dependent protein kinase reveals an inhibitory role of Ku in late S–G2 phase DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44413–44418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce AJ, Hu P, Han M, Ellis N, Jasin M. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3237–3242. doi: 10.1101/gad.946401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominguez-Bendala J, Masutani M, McWhir J. Down-regulation of PARP-1, but not of Ku80 or DNA-PKcs, results in higher gene targeting efficiency. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buerstedde JM, Takeda S. Increased ratio of targeted to random integration after transfection of chicken B cell lines. Cell. 1991;67:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90581-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrie PC, Russell DW. Gene targeting with viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2005;12:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Dyck E, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, West SC. Binding of double-strand breaks in DNA by human Rad52 protein. Nature. 1999;398:728–731. doi: 10.1038/19560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zentilin L, Marcello A, Giacca M. Involvement of cellular double-stranded DNA break binding proteins in processing of the recombinant adeno-associated virus genome. J Virol. 2001;75:12279–12287. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12279-12287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inagaki K, Ma C, Storm TA, Kay MA, Nakai H. The role of DNA-PKcs and Artemis in opening viral DNA hairpin termini in various tissues in mice. J Virol. 2007;81:11304–11321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller DG, et al. Large-scale analysis of adeno-associated virus vector integration sites in normal human cells. J Virol. 2005;79:11434–11442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11434-11442.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song S, et al. DNA-dependent PK inhibits adeno-associated virus DNA integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307833100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vasileva A, Linden RM, Jessberger R. Homologous recombination is required for AAV-mediated gene targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3345–3360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen C, Kurimasa A, Brenneman MA, Chen DJ, Nickoloff JA. DNA-dependent protein kinase suppresses double-strand break-induced and spontaneous homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3758–3763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052545899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. A backup DNA repair pathway moves to the forefront. Cell. 2007;131:223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staunton JE, Weaver DT. scid cells efficiently integrate hairpin and linear DNA substrates. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3876–3883. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.