Abstract

Age structure at the neighborhood level is rarely considered in contextual studies of health. However, age structure can play a critical role in shaping community life, the availability of resources, and the opportunities for social engagement—all factors that, research suggests, have direct and indirect effects on health. Age structure can be theorized as a compositional effect and as a contextual effect. In addition, the dynamic nature of age structure and the utility of a life course perspective as applied to neighborhood effects research merits attention. Four Chicago neighborhoods are summarized to illustrate how age structure varies across small space, suggesting that neighborhood age structure should be considered a key structural covariate in contextual research on health. Considering age structure implies incorporating not only meaningful cut points for important age groups (e.g., proportion 65 years and over) but attention to the shape of the distribution as well.

KEYWORDS: Affluence, Collective efficacy, Life course, Neighborhood social context, Social capital, Poverty, Residential stability.

Introduction

Individual-level demographic factors are considered key covariates in the study of human health and well-being. Age is, in general, the single individual-level demographic characteristic that impacts health most significantly. Although heterogeneity exists at each age, and may increase with age, the inverse relationship between age and health is consistent across time, population groups, and disease states; analyses of health status would be considered incomplete without consideration of age.

Studies of neighborhood effects on health outcomes, with few exceptions, include individual-level controls such as age in their examination of neighborhood social processes. Much less common is the consideration of age at the neighborhood level, or the age structure of the community, although we do see examples of analyses where the proportion of children1 or the proportion of older adults2 are incorporated. Inattention to age in empirical analyses is the result of inattention to age in the conceptualization of neighborhood context and neighborhood social processes. Theoretical developments related to social capital3,4 and contemporary elaborations of social disorganization theory5 have not incorporated the role of age structure. Age structure merits attention as a key structural variable in neighborhood-level investigations of health, in addition to commonly considered factors such as poverty, affluence and residential stability. Three tenets underscore the need to account for age structure at the neighborhood level and highlight the potential benefits of a focus on age structure in its own right: age structure as a (1) compositional effect, (2) contextual effect, and (3) dynamic factor. In addition, the extent to which analyses of age structure should attend to the shape of the distribution, rather than the tails alone, is considered. Four Chicago neighborhoods are profiled to illustrate the association of age with key structural factors at the neighborhood level and to motivate discussion of age, and aging, as a neighborhood-level phenomenon that may affect health.

Age Structure as a Compositional Effect

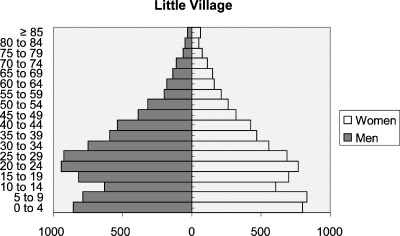

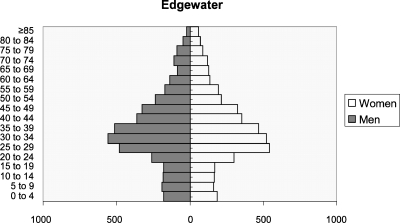

Age structure indicates the distribution of individual ages or the composition of the community. To focus on age composition means to examine the impact of both the presence and concentration of a specific age group.6 The urban planning literature indicates that age structure drives community infrastructure.7–9 The Chicago neighborhoods of Little Village — a primarily Latino community on the West Side — and Edgewater, a primarily White community near Lake Michigan, provide an illustration (Figures 1 and 2) are based on neighborhood clusters of two to three census tracts for the year 2000.5,9,10 The population pyramid for Little Village reveals a very young population. In the general case, age structure of this form encourages health promotion, accessible public space, and the presence of institutions such as health clinics. However, it also may mean that the community has fewer economic resources to draw upon; the small number of working age persons relative to those at younger ages suggests demands for education and recreational space. The neighborhood of Edgewater provides a stark contrast to that of Little Village. Burgeoning with residents aged 25–39, it has neither a significant representation of children nor older adults. This pyramid typifies a neighborhood that is dominated by those with economic resources and, potentially, fewer dependents.11 Little Village may be comprised of people who are relatively young and healthy, but may not have the economic resources to invest in high-quality health and health-enhancing services possessed by Edgewater's primarily working age population.

Figure 1.

Population of the Little Villiage Neighborhood, by Age and Sex, 2000.

Figure 2.

Population of the Edgewater Neighborhood, by Age and Sex, 2000.

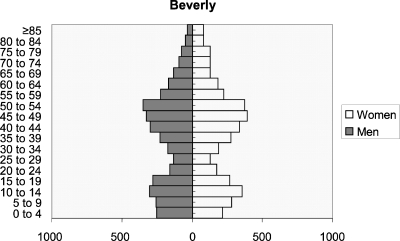

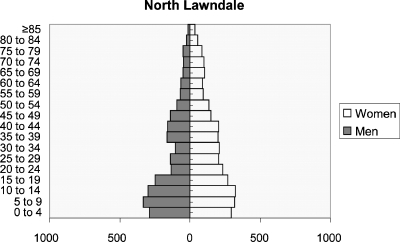

In contrast, Beverly — a primarily African American community, with a substantial number of Whites, on the south side — and North Lawndale — a primarily African American community on the west side and adjacent to Little Village — are neighborhoods whose age pyramids are relatively cylindrical; that is, they have representation across the age continuum (Figures 3 and 4). Beverly's hourglass shape suggests a neighborhood with higher levels of age integration and one dominated by families. This may translate into higher rates of residential stability and the opportunity for older adults to age in place.12 Residentially stable, age-integrated communities may contribute to perceptions of security, provide for greater exchange among neighbors, and offer the impetus to invest in one’s surroundings13; all of these factors may enhance health.14 Age composition then, provides the foundation for certain community-level properties to emerge. It is these emergent properties to which we now turn.

Figure 3.

Population of the Beverly Neighborhood, byAge and Sex, 2000.

Figure 4.

Population of the North Lawdale Neighborhood, by Age and Sex, 2000.

Age Structure as a Contextual Effect

Age groups, or cohorts, affect or contribute to a community apart from the aggregation of their age-associated activities or needs. In other words, age structure as a contextual effect refers to an emergent phenomenon—something that cannot be reduced to characteristics of individual residents. Macro-level research on crime provides an illustration. Criminologists consider age structure to be important to the extent that the presence of younger persons is predictive of criminal activity. Specifically, criminological research indicates that the presence of young adults (i.e., ages 15–25) is associated with higher rates of crime.15,16 The first and potentially most obvious reason is that younger people are more likely to commit crimes. This speaks to the compositional effect. It is not just the aggregation of these events, however, that may compromise community life. Increased engagement in criminal activity can lead to generalized feelings of fear and distrust and may contribute to the deterioration of social organization. So, in this example, it is the contextual effect of the presence of younger adults that has an important and independent effect on the social organization of the community. Individual youth commit crimes, the accumulation of which affects the neighborhood crime rate, but it is the proportion of persons in the neighborhood who are youth that exerts independent influence on the capacity to maintain social control and reduce fear. Depleted social organization contributes to poor health.17 Paradoxically, young adults may be healthier but may not necessarily bring “health” to the community. This illustration offers a provocative set of hypotheses; the extent to which a youth-dominated community leads to instability, which then leads to poor health, remains relatively unexplored.

A second contextual example stems from the presence of older adults. The greater prevalence of conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and stroke among older adults could mean that older residents are confined to their homes and are thus less likely to engage in community life. Although their “circumference of turf” may shrink,18 evidence suggests that older persons may be readily engaged in social network formation19,20 and may remain active members of the community. Knowledge of the community developed over time, coupled with a constant presence, provides for continuity and stability.21,22 The social capital/civil society construct points to a role for age structure that is counterintuitive; the emergent effect of age structure implies that age may mean something very different once health at the individual level is controlled. For instance, the presence of older adults in the community contributes to the density of networks and the level of collective efficacy.23 In the case of the 1995 Chicago heat wave, the presence of older adults was protective against heat-related mortality.24 On the neighborhood level, communities dominated by older adults may be “healthier” than their youth-dominated counterparts.

The correlations in Table 1 suggest a contextual effect for age. For instance, the role of age structure for social interaction/exchange and collective efficacy indicates that the presence of a young population base is associated with depleted social resources, while the opposite is true as the proportion of older residents increases (particularly those 65+). Levels of poverty, affluence, residential stability, social interaction/exchange, and collective efficacy—shown in previous literature to have implications for resident well being5,17,25—vary significantly in their associations with age strata.

Table 1.

Correlations among neighborhood-level variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Percent <18 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2. Percent 18–64 | −0.777 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3. Percent 65+ | −0.593 | −0.046 | 1.000 | |||||

| 4. Poverty | 0.752 | −0.572 | −0.447 | 1.000 | ||||

| 5. Affluence | −0.679 | 0.539 | 0.388 | −0.768 | 1.000 | |||

| 6. Residential stability | 0.117 | −0.321 | 0.223 | −0.300 | 0.365 | 1.000 | ||

| 7. Collective efficacy | −0.536 | 0.263 | 0.512 | −0.653 | 0.700 | 0.382 | 1.000 | |

| 8. Social interaction/exchange | −0.184 | 0.033 | 0.248 | −0.181 | 0.298 | 0.167 | 0.554 | 1.000 |

The Dynamic Nature of Age Structure

Unlike other basic demographic factors (e.g., sex, race), age is dynamic in the sense that individuals continually age. This demographic imperative has important implications for the role of age structure in health. The provision of neighborhood-based health-enhancing resources must be responsive to the ever-changing needs of the population, even in a stable neighborhood. Paradoxically, stability in a population leads to a change in age structure; the only way to maintain a constant age structure is to alter neighborhood composition through in- or out-migration. Hence, compositional and contextual effects of age are constantly in flux.

Life course theory provides a framework for understanding the dynamic process of age structure. A life course approach implies attention to a trajectory, to timing and sequencing, and to critical turning points.26 It is the timing and sequencing of such changes that could be incorporated into analyses of health. Processes related to gentrification provide a case in point. The timing of gentrification, whether it is a short or long process, and whether it happens before, after or in concert with other forces (e.g., implosion of high-rise low-income housing) shapes the pathway to neighborhood change. To continue with the example of Edgewater, an age structure of this form typifies a community that is gentrifying, but this gentrification could take on different forms. For instance, a churning neighborhood (one that continually attracts young people) implies a very different neighborhood trajectory than a turning neighborhood (one that gentrified at one point in time and residents now age in place). Young cohorts that replace themselves may be less likely to invest in long-term neighborhood improvements that have downstream effects on health. Indeed, even if cohorts plan to age in place, the age at which they entered the neighborhood (e.g., young adult, early parent) may be important to neighborhood-based experiences and interactions and the role they play in later life health.

Moreover, communities, like individuals, experience turning points.27,28 Changing age structures may impose turnings points, just as a new housing development, a new highway, or a new congressional representative would. Age structure “tipping points” may be apparent in voting behavior, social network density, or in the level of physical and social disorder in the community.29 Attention to age-associated turning points could yield age-appropriate housing and civic services, which could affect health and the ability to seek and obtain health-related resources.

Summary

Theories from urban planning, criminology, and sociology of the life course have been invoked to examine the role of age structure in neighborhood-based research. Framing a neighborhood as we would a population group introduces methods and approaches that could enhance our understanding of the neighborhood-health relationship. Additional issues merit consideration. First, the interplay between age and other structural variables is important to explore, as Table 1 suggests. An affluent community with a large proportion of children calls to mind a very different context than an impoverished community with the same age structure. Attention to such interactions, theoretically and empirically, is necessary to fully incorporate age structure into neighborhood-level research. Second, age structure might have different effects depending on the level of aggregation. On the street level, age structure may be predictive of social network formation. On the neighborhood level, it may be associated with the number of parks, schools, or clinics, as discussed above. On the state level, it may affect Medicaid reimbursement. Age structure may be more or less influential depending on the outcome and the area under study. Third, neighborhood-level measures of central tendency (e.g., mean age) may not adequately capture the more subtle impact of age across the life span. Covariates that capture the shape of the distribution, rather than the tails alone, could provide critical information about the role of age in health. An extension of this approach could include an examination of age position, or an individual’s age relative to others; the effects of being either older or younger than the majority of one’s neighbors are not known.

Finally, it is important to further investigate the extent to which age structure contributes to health via such mechanisms as community-level social cohesion or social isolation.30,31 For instance, recent research by Small (2002),32 characterizing a Puerto Rican enclave in Boston, indicates that age influences perceptions of neighborhood continuity and change and the motivation to maintain social capital. Age may affect perceptions, participation in community life, and, as outlined above, may alter the context of community in unexpected ways. Age, as a structural antecedent, may thus have important effects on health and may have important effects on the social processes that shape health. Consequently, age structure may be critical to characterizing neighborhood context.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge Christopher Browning and David Meltzer for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Many thanks to Danielle Wallace for assistance with the construction of the population pyramids. Support for this research was provided by R01AG022488 from the National Institute on Aging.

References

- 1.Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M, Chow J. Community-level factors and child maltreatment rates. Child Dev. Oct 1995;66(5):1262–1276. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wen M. Racial disparities in self-rated health at older ages: what difference does the neighborhood make? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Jul 2005;60(4):S181–190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociology. 1998;24:1–24. [DOI]

- 4.Kawachi I, Berkman L, eds. Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- 5.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;227:918–923. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Serow WJ. Economic and social implications of demographic patterns. In: Binstock RH, George LK, eds. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. Vol 5. San Diego: Academic; 2001:86–102.

- 7.Rogerson PA, Plane DA. The dynamics of neighborhood age composition. Environ Plan A. Aug 1998;30(8):1461–1472. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cowgill DO. Residential segregation by age in American metropolitan areas. J Gerontol. 1978;33(3):446–453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Beguin H. The effect of urban spatial structure on residential mobility. Ann Reg Sci. Nov 1982;16(3):16–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Earls F, Buka SL. Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods: Technical Report. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Justice; 1997.

- 11.Congdon. An analysis of population and social change in London wards in the 1980s. Trans Inst Br Georgr. 1989;14(4):478–491. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Chevan A. Age, housing choice, and neighborhood age structure. Am J Sociol. 1982;87(5):1133–1149. [DOI]

- 13.Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House 1961.

- 14.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.South S, Messner S. The sex ratio and women's involvement in crime: a cross-national analysis. Sociol Q. 1987;28:171–188. [DOI]

- 16.Steffensmeier DJ, Allan EA, Harer MD, Streifel C. Age and the distribution of crime. Am JSociol. Jan 1989;94(4):803–831. [DOI]

- 17.Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley TG. Assessing ‘neighborhood effects’: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociology. Aug 2002;28:443–478.

- 18.Skogan WG. Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1990.

- 19.Sherman SR, Ward RA, LaGory M. Socialization and aging group consciousness: the effect of neighborhood age concentration. J Gerontol. Jan 1985;40(1):102–109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Oh J-H. Assessing the social bonds of elderly neighbors: the roles of length of residence, crime victimization, and perceived disorder. Sociol Inq. 2003;73(4):490–510. [DOI]

- 21.Putnam RD. Bowling Alone. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000.

- 22.Cannuscio C, Block J, Kawachi I. Social capital and successful aging: the role of senior housing. Ann Intern Med. Sep 2 2003;139(5 Pt 2):395–399. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wen M. Aging, neighborhoods, and health: exploring the reciprocal relationship between community context and the health of older persons; 2006.

- 24.Browning CR, Wallace DM, Feinberg SL, Cagney KA. Neighborhood social processes, physical conditions, and disaster-related mortality: the case of the 1995 Chicago heat wave. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71:665–682.

- 25.Shaw CR, McKay HD. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas: A Study of Rates of Delinquents in Relation to Differential Characteristics of Local Communities in American Cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1969.

- 26.O'Rand AM. The precious and the precocious: understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. Gerontologist. Apr 1996;36(2):230–238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Elder GH. Children of the Great Depression. Boulder: Westview; 1999.

- 28.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993.

- 29.Massey DS, Gross AB, Shibuya K. Migration, segregation, and the geographic concentration of poverty. Am Sociol Rev. 1994;59(3):425–445. [DOI]

- 30.Klinenberg E. Heatwave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002.

- 31.Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: the Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987.

- 32.Small M. Culture, cohorts, and social organization theory: understanding local participation in a Latino housing project. Am J Sociol. 2002;108:1–54. [DOI]