Abstract

Past research has shown that women who either have sex with women or who identify as lesbian access less preventive health care than other women. However, previous studies have generally relied on convenience samples and have not examined the multiple associations of sexual identity, behavior and health care access/utilization. Unlike other studies, we used a multi-lingual population-based survey in New York City to examine the use of Pap tests and mammograms, as well as health care coverage and the use of primary care providers, among women who have sex with women and by sexual identity status. We found that women who had sex with women (WSW) were less likely to have had a Pap test in the past 3 years (66 vs. 80%, p<0.0001) or a mammogram in the past 2 years (53 vs. 73%, p=0.0009) than other women. After adjusting for health insurance coverage and other factors, WSW were ten times [adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 9.8, 95% confidence interval (CI), 4.2, 22.9] and four times (AOR, 4.0, 95% CI 1.3, 12.0) more likely than non-WSW to not have received a timely Pap test or mammogram, respectively. Women whose behavior and identity were concordant were more likely to access Pap tests and mammograms than those whose behavior and identity were discordant. For example, WSW who identified as lesbians were more likely to have received timely Pap tests (97 vs. 48%, p<0.0001) and mammograms (86 vs. 42%, p=0.0007) than those who identified as heterosexual. Given the current screening recommendations for Pap tests and mammograms, provider counseling and public health messages should be inclusive of women who have sex with women, including those who have sex with women but identify as heterosexual.

Keywords: Health care access, Health care utilization, Mammogram, Pap test, Preventive care, Random digit dial, Sexual behavior, Sexual identity, Stratified sample, Women who have sex with women.

Introduction

Both the 1999 Institute of Medicine Report and Healthy People 2010 have identified that, as a group, people defined by same sex sexual orientation may experience poor health.1,2 Research has found that women who have sex with women are less likely to utilize preventive clinical care.3–9 However, the health of women who have sex with women (WSW) has been hard to accurately characterize due to methodological limitations of previous studies.1,6 First, most research uses convenience samples, resulting in findings that may not be generalizable. Second, most compare women who have sex with women with general population estimates from other studies (that include women who have sex with women). Determining whether the experiences of WSW differ from those of the general population across studies is difficult. Third, most previous research identifies women who have sex with women by sexual identity and rarely examines stratifications of sexual behavior and identity simultaneously. We thus do not have a clear understanding of how women who identify as lesbian exhibit characteristics or health behaviors differently than women who have sex with women but do not identify as lesbian.

To address these gaps in knowledge, we used a large population-based sample in New York City to compare the characteristics of women who have sex with women with those who do not. We then examined the relationship between sexual behavior and both health care access (health care coverage and having a primary health care provider) and health care utilization (Pap test and mammogram use). Among women who had sex with women, we compared these factors between individuals who identify as heterosexual (but have sex with women) and those who identify as lesbian, exploring the impact of sexual identity on Pap test and mammogram use.

Methods

Data Collection and Sample

Data were collected through two cross-sectional, computer-assisted telephone surveys of adult New York City residents from May to July 2002 and from May 2004 to February 2005 (referred to as the 2004 survey). A stratified random sample design was employed; the goal was to conduct approximately 300 interviews in each NYC neighborhood; neighborhoods were defined by 33 zip code aggregations in 2002 and 34 in 2004. The sampling frame was constructed through a list of random digit telephone numbers provided by a commercial vendor, and ten attempts were made to reach each household on the list. Potential respondents were asked their zip codes, and the interviews were discontinued if the quota for the neighborhood had been met. One adult (aged 18 years or older) was randomly selected from each eligible household. Our final samples (N=9,764 in 2002 and N=9,585 in 2004) represented 64% of eligible households contacted in 2002 and 59% in 2004.10

Survey Instrument

The survey instruments were adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)11 and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).12 The surveys included questions regarding sociodemographics, health status, health care access, use of clinical preventive services, health behaviors, health conditions, and home and community environment. In 2002, respondents were asked their household income, which was categorized in ranges. In 2004, household income was categorized into federal poverty levels. Using the federal income thresholds and the number of people in the household (obtained from the survey), we imputed federal poverty levels in the 2002 data. To determine sexual orientation, respondents 18–64 years of age in 2002 were asked, “During the past 12 months, have you had sex with only males, only females, or with both males and females?” In 2004, all women 18 and older were asked, “During the past 12 months, with how many men have you had sex?” And, “During the past 12 months, with how many women have you had sex?” Women who had sex with only females or both males and females were counted as having had sex with women. In 2004, respondents were also asked, “Which of the following best describes you: heterosexual, gay or lesbian or bisexual?” Because the 2002 data were restricted by age, all analyses were limited to adult women age 18–64. Only three women (1.1%) over the age of 64 identified as having had sex with women in 2004.

In 2002 and 2004, women were asked if they'd ever had a Pap test, and those who were asked how long it had been since their last Pap test. Likewise, women age 40 years and older were asked if they'd ever had a mammogram, and those who had were asked how long it had been since their last mammogram. In 2002, respondents were asked what type of health care coverage they used most often to pay for care. In 2004, they were asked if they had any type of health care coverage, and if so, what type they used most often. To determine whether women had a primary health care provider (PCP), participants in both surveys were asked, “Do you have one person you think of as your personal doctor or health care provider?” Respondents were also asked if they were employed; individuals who were in school or homemakers were classified as being out of the market. Surveys were conducted in English, Spanish, Chinese, Greek, Korean, Russian, Yiddish, Polish and Haitian Creole in 2002 and in over 25 languages in 2004.

Statistical Analysis

The two data sets were combined into a single data set, which was weighted to account for unequal selection probabilities and non-response. For each data set, primary weights were calculated for each respondent, consisting of the inverse of the probability of selection (number of adults in each household divided by number of residential telephone lines). Post-stratification weights were used to adjust the sample estimates according to the precise age, race/ethnicity, and gender composition of each sampling stratum (neighborhood). All univariate and bivariate analyses were weighted to the NYC population and age-standardized to the U.S. Standard Population 2000.

We described the socio-demographic characteristics, health care access and utilization of women who did and did not have sex with women. To compare these groups of women, we calculated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (socio-demographic characteristics) and Student t‐tests (health care access and utilization). Next, we conducted four multivariate logistic regression analyses using the 2004 data set, examining the associations of sexual behavior with (1) no Pap test in the past 3 years, (2) no mammogram (among women age 40 years and older) in the past 2 years, (3) no healthcare coverage, and (4) no primary care provider. Models were built in a forward stepwise manner, and individual variables were added in the order of importance, based on their significance in both the bivariate analyses and the literature. Then, using the 2004 data set to examine women who had sex with women, we compared socio-demographic characteristics, health care access and health care utilization among those who identified as heterosexual with those who identified lesbian, also using Student t tests. Information on the proportion of WSW who identify as bisexual is provided, but there were too few bisexually identified women to examine characteristics of this group and make statistical comparisons. Analyses were also conducted on health care utilization among women who did not have sex with women and identified as heterosexual. The SAS (Cary, NC, USA) statistical package was used for data management, and SAS-callable SUDAAN (RTI, NC) was used to obtain appropriate standard errors for the point estimates (PROC DESCRIPT) and to conduct the multiple logistic regression analyses (PROC RLOGIST).

Results

Overview of Women who Had Sex with Women

Using data from the 2002 and 2004 surveys, an average of 4.5% (estimated population = 81,026) of sexually active NYC women (18–64) reported having had sex with women in the prior year (3.8% in 2002 and 4.7% in 2004) (Table 1). There were no differences in poverty level or employment status between WSW and women who did not report having sex with women in the past year. WSW were more likely to be younger than older, to have been born in the USA, and to be separated, never married or living with an unmarried partner than to be currently married. WSW were also marginally more likely to be black than white and to have higher levels of education, although these findings were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics among women who had sex with women in New York City (ages 18–64), 2002 and 2004

| Had sex with women, N=269, % (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) (odds of having had sex with women) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4.5 (3.9, 5.2) | ||

| Percent of poverty level, % | <100 | 4.3 (2.7, 7.0) | Ref |

| 100–199 | 4.8 (3.5, 6.4) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.9) | |

| 200–399 | 5.3 (3.9, 7.2) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.1) | |

| 400–599 | 3.9 (2.7, 5.6) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.7 | |

| 600 or more | 5.1 (3.7, 7.1) | 1.1 (0.7, 2.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 4.4(3.5, 5.5) | Ref |

| Black | 6.2 (4.9, 7.8) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.1) | |

| Hispanic | 4.1 (2.9, 5.8) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | |

| Asian | 0.8 (0.3, 2.2) | 0.2 (.06, 0.5) | |

| Country of origin | US-born | 5.4 (4.6, 6.3) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8) |

| Foreign-born | 3.2 (2.3, 4.3) | Ref | |

| Educationa | <HS | 3.1 (1.7, 5.6) | Ref |

| HS | 4.6 (3.3, 6.4) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.3) | |

| Some college | 4.4 (3.2, 6.1) | 1.6 (0.9, 3.1) | |

| College grad | 4.1 (3.2, 5.2) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.7) | |

| Age | 18–24 | 6.4 (4.7, 8.7) | Ref |

| 25–44 | 4.4 (3.7, 5.3) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | |

| 45–64 | 3.7 (2.7, 5.1) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | |

| Marital status | Married | 2.2 (1.7, 3.0) | Ref |

| Divorced | 3.9 (1.9, 8.1) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | |

| Widowed | 3.0 (1.3, 6.7) | 1.5 (0.6, 3.6) | |

| Separated | 6.2 (3.3, 11.5) | 1.2 (1.1, 4.4) | |

| Never married | 8.1 (5.9, 11.0) | 3.2 (2.1, 4.7) | |

| Lives with partner | 11.7 (8.1, 16.7) | 5.7 (3.5, 9.1) | |

| Employment | Employed | 5.0 (4.2, 5.9) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) |

| Not employed | 7.5 (5.0, 11.1) | Ref | |

| Out of market | 2.3 (1.6, 3.4) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | |

aAmong those age 25 or older.

Sexual Behavior and Health Care Patterns

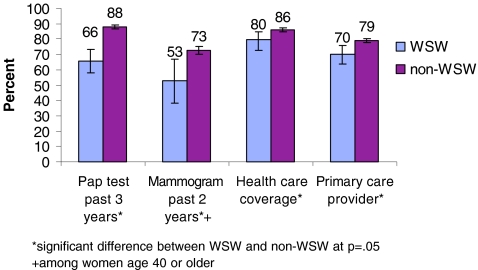

In terms of health care utilization, WSW were significantly less likely than other women to have had a Pap test in the past 3 years (66 vs. 88%, p<0.0001) and to have had a mammogram in the past 2 years (53 vs. 73%, p=0.0009). They were also less likely to have health care coverage (80 vs. 86%, p=0.03) and to have a primary care provider (70 vs. 79%, p=0.007) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of health care access and utilization indicators among women who had sex with women and non-WSW (ages 18–64), New York City 2002 and 2004.

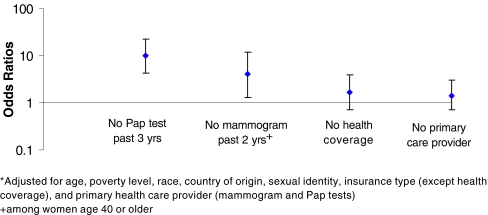

Figure 2 indicates the results of multivariate models predicting having had no Pap test in the past 3 years, no mammogram in the past 2 years, no health care coverage, and no primary health care provider. After accounting for other factors, including insurance status, primary care provider and sexual identity, women who had sex with women were ten times more likely to have had no Pap test in the past 3 years than non-WSW (OR = 9.8, 95% CI: 4.2, 22.9). Women who had sex with women were four times more likely to have had no mammogram in the past 2 years than non-WSW (OR = 4.0, 95% CI: 1.3, 12.0).

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios*—women who had sex with women compared to non-WSW (ages 18–64), New York City 2004.

Figure 2 also presents results from the two models predicting no health care coverage and no primary care provider. After adjusting for demographics and other covariates, WSW had slightly higher rates of no health care coverage than other women, but the difference was not significant (OR = 1.7, 95% CI: 0.7, 3.9). Similarly, after accounting for other factors, women who had sex with women were slightly more likely to have no primary care provider, although this comparison was also not significant (OR = 1.4, 95% CI: 0.7, 3.0).

Sexual Identity and Healthcare Patterns

In 2004, women were also asked about their sexual identity. Irrespective of sexual behavior or activity, 97% (estimated population = 2,465,883) of all women (18–64) identified as heterosexual, 1.5% (estimated population = 39,433) as lesbian and 1.5% (estimated population = 37,840) as bisexual. Among WSW, 43% identified as heterosexual, 39% identified as lesbian, and 18% as bisexual (Table 2). Compared to WSW who identified as heterosexual, women who identified as lesbian were more likely to be U.S.-born (90 vs. 62%, p=0.0002), to have never married (64 vs. 24%, p<0.0001), and to be living with an unmarried partner (18 vs. 4%, p<0.01) and were less likely to have their highest level of education be high school (10 vs. 36%, p=0.04) and to be married (6 vs. 53%, p<0.0001). Women who identified as lesbian were also marginally more likely to be white than those who identified as heterosexual (46 vs. 35%, p=0.09).

Table 2.

Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics and health care access and utilization indicators among women who had sex with women in New York City (ages 18–64), 2004

| Identify as heterosexual N=63, % | Identify as lesbian N=53, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total percent | 43.2 | 39.4 | |

| Percent of poverty level | <100 | 14.7 | 29.2 |

| 100–199 | 19.6 | 8 | |

| 200–399 | 21.8 | 18.2 | |

| 400–599 | 22.6 | 18.6 | |

| 600% or more | 21.4 | 26 | |

| Race | Whitea | 34.8 | 46.3 |

| Black | 33.7 | 29.7 | |

| Hispanic | 28.1 | 24 | |

| Asian | 3.4 | 0 | |

| Country of origin | US-bornb | 61.6 | 89.6 |

| Foreign-born | 38.4 | 10.4 | |

| Educationc | <HS | 2.2 | 5.8 |

| HSb | 36 | 10.3 | |

| Some College | 19.2 | 29.5 | |

| College grad | 42.7 | 54.4 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 15.2 | 15.8 |

| 25–44 | 59.7 | 64.7 | |

| 45–64 | 25.1 | 19.5 | |

| Marital status | Marriedb | 53.2 | 6.4 |

| Divorced | 9.4 | 4.5 | |

| Widowed | 4.6 | 5 | |

| Separated | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Never marriedb | 24.1 | 63.5 | |

| Lives with partnerb | 3.6 | 18.2 | |

| Employment | Employed | 66.6 | 76.5 |

| Not employed | 17.3 | 14 | |

| Out of market | 16.1 | 9.5 | |

| Pap test past 3 years | Yesb | 48 | 96.6 |

| Mammogram past 2 yearsd | Yesb | 41.7 | 85.9 |

| Any health care coverage | Yes | 78.5 | 87.2 |

| Primary care provider | Yes | 80 | 76.7 |

aStatistical difference between groups at p=0.10.

bStatistical difference between groups at p=0.05.

cAmong those age 25 or older.

dAmong women age 40 or older.

To understand the effect of sexual identity on health care utilization patterns, we examined Pap test and mammogram use among WSW, stratified by sexual identity. We found that women with concordant behavior and identity had higher utilization of health care services than those who had discordant behavior and identity. Among WSW, women who identified as lesbian (concordant) were more likely than heterosexually identified WSW (discordant) to have had a Pap test in the past 3 years (97 vs. 48%, p<0.0001) or a mammogram in the past 2 years (86 vs. 42%, p=0.0007). Examining concordance between identity and behavior among non-WSW was not feasible, as there were few non-WSW who identified as lesbian (<1%). However, among non-WSW who identified as heterosexual (concordant), utilization patterns were high and comparable to WSW who identified as lesbian (concordant); 89% of non-WSW who identified as heterosexuals had a Pap test in the past 3 years, and 78% of this group had a mammogram in the past 2 years. In terms of health care coverage and use of a primary care provider among WSW, no difference was found between those who identified as heterosexual and lesbian.

Discussion

In this paper, we used a population-based survey to describe sexual practices and sexual identity in a population-based sample of adult women in New York City. Of sexually active women ages 18–64, almost 5% reported having had sex with women in the past year, and 1.5% of women in that age range identified as lesbian, reinforcing the importance of examining sexual behavior, not just identity, in order to understand health care practices among WSW. In our study, the prevalence of lesbian-identified women was comparable to the 0.8% found in the Nurses Health Study II in 1995.13

Compared with non-WSW, WSW were ten times more likely to not have received timely Pap tests and four times more likely to not have received timely mammograms, even after accounting for measures of health care access, sexual identity and other potentially confounding factors. Previous population-based studies found women who identified as lesbian to be less likely to have had a Pap test than those who identified as heterosexual.14–16 All of these studies, however, examined health care utilization among women who identified as lesbians; none looked at behavior.

When we examined the effect of sexual identity and behavior together on health care utilization, we found that behavior–identity concordance was an important factor in health care utilization: Women whose behavior was concordant with their identity were more likely to utilize services than those whose behavior and identity were discordant. For example, among WSW, women who identified as lesbian were more likely to have had timely Pap tests and mammograms tests than those who identified as heterosexual.

Previous research has suggested that WSW may not feel comfortable seeking care because they feel unable to disclose their sexual orientation to their general practitioners.17 Our data suggest that this might be particularly true among women whose identity is discordant from their behavior; these women may be even more uncomfortable discussing sexual issues with health care providers and, therefore, may be more likely to avoid care. Other studies have indicated that WSW have had negative experiences with providers due to their sexuality, including homophobic attitudes, embarrassment, anxiety, inappropriate reactions, rejections and discrimination.18–20 One study of lesbians in the UK found that they were less likely to report good experiences with providers around Pap tests and breast screenings than non-lesbian identified women and that positive previous experiences with health care providers were associated with increased screening.21 Similarly, a Boston study found women who identified as lesbian to have had more experiences with judgmental or insensitive providers than those who identified as heterosexual.14 These fears, based on past experience or the experiences of others, are sometimes enough to avoid care, delay care, or only seek care for the worst, most advanced problem.9

Another potential reason that WSW seek preventive care less frequently than women who do not have sex with women is a misperception of their risks for certain conditions.21 Prior research suggests that many women, and their providers, believe that WSW are not at risk for cervical cancer, despite the fact that four out of five women who have sex with women have also had sex with men. Further, WSW are often at higher risk for breast and ovarian cancers (due to maternal risk factors such as child bearing patterns) than heterosexual women.6,9,22,23 WSW require the same routine screening and preventive services that heterosexual women receive.8

We identified few demographic differences between WSW and non-WSW; WSW were more likely to be younger, U.S.-born, and either separated, never married or living with an unmarried partner. They were marginally more likely to be black and to have a higher level of education than non-WSW. No differences were found in health insurance status. Previous studies on lesbian and heterosexual women have found lesbians to be more likely to be younger, to have higher education levels, to be white, and to have less health insurance.3,15 When we stratified by both behavior and identity, we found health insurance status to be comparable across all groups, including lesbian-identified and heterosexually identified WSW. Lesbian-identified WSW were, however, more likely to be white than heterosexually identified WSW.

This study used two large, population-based, cross-sectional surveys, which were conducted in multiple languages and were broadly representative of the population of NYC. Nevertheless, the study has a number of limitations. First, some of the questions varied between years. The sexual behavior, health care coverage and income questions were phrased or categorized slightly differently between 2002 and 2004, and the sexual identity question was only asked in 2004. Second, the surveys represent only non-institutionalized NYC adults with working residential telephones. Third, because some questions were only asked of individuals who were less than 65 years of age, these results can only be generalized to that age group. Fourth, the cross-sectional design represents one point in time; thus, the temporality of some associations cannot be inferred. Fifth, all data are self-reported, and there is the danger of a social response bias or low identification of same-sex behavior through a telephone survey. However, anonymous surveys can reduce socially desirable responding,24 and documented levels of reliability and validity of the questions in the BRFSS, on which these surveys were based, have been shown to be relatively high.25,26 Finally, for some comparisons, the numbers available for analysis were small, which may have made statistically significant findings difficult to obtain. For example, we were unable to examine the association between WSW identifying as bisexual and health care utilization.

Despite similar levels of healthcare coverage, women who have sex with women do not access preventive care as much as other women. This is particularly true among women who have sex with women but identify as heterosexual. Given the national guidelines to screen for breast and cervical cancers27,28 and the importance of Pap tests and mammograms in identifying cancers and enabling early treatment,29,30 it is important to engage this population in care.

For some women, a lack of care may be due to a discomfort with medical providers, while for others it may be the result of a misperception of risk. Provider training and education is essential, then, to increase women's use of primary healthcare, Pap tests, and mammograms. Education among women is also necessary in order to increase women's use of important healthcare services. In our study, 43% of WSW identified themselves as heterosexual; public health messages targeted to women who have sex with women should thus reach beyond women who identify themselves as lesbians and target the general population.

Footnotes

Kerker and Thorpe are with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Division of Epidemiology, New York, NY, USA; Mostashari is with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Division of Health Care Access and Improvement, 225 Broadway, 23rd fl, rm 10, #10, New York, NY 10007, USA.

References

- 1.Bradford J, White J, Honnold J, Ryan C, Rothblum E. Improving the accuracy of identifying lesbians for telephone surveys about health. Women's Health Issues. 2001;11(2):126–137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hughes TL, Jacobson KM. Sexual orientation and women's smoking. Current Women's Health Reports. 2003;2:254–261. [PubMed]

- 3.Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, Whitlock E, Charney P, Carter RA. Sexual orientation and health. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:843–853. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Aaron DJ, Markovic N, Danielson ME, Honnold JA, Janosky JE, Schmidt NJ. Behavioral risk factors for disease and preventive health practices among lesbians. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:972–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.McNair RP. Lesbian health inequalities: a cultural minority issue for health professionals. Med J Aust. 2003;178:643–645. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, et al. Cancer-related risk indicators among preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Roberts SJ, Sorensen L. Health related behaviors and cancer screening of lesbians: results from the Boston lesbian health project. Women Health. 1999;28(4):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Spinks VS, Andrews J, Boyle JS. Providing health care for lesbian clients. J Transcult Nurs. 2000;11(2):137–143. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bernhard LA. Lesbian health and health care. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2001;19:145–177. [PubMed]

- 10.Mostashari FM, Kerker BD, Hajat A, Miller N, Frieden TF. Smoking practices in New York City: the use of a population-based survey to guide policy making and programming. J Urban Health. 2005;82(1):58–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002.

- 12.CDC. National Health Interview Survey. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002.

- 13.Case P, Austin B, Hunter DJ, et al. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses' Health Study II. J Women Health. 2004;13(9):1033–1047. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bowen DJ, Bradford JB, Powers D, et al. Comparing women of differing sexual orientations using population-based sampling. Women Health. 2004;40(3):19–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Diamant AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, Gelberg L. Health behaviors, health status, and access to and use of health care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Roberts SJ, Patsdaughter CA, Grindel CG, Tarmina MS. Health related behaviors and cancer screening of lesbians: results of the Boston lesbian health project. Women Health. 2004;39(4):41–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Carr SV, Scoular A, Elliott L, Ilett R, Meager M. A community based lesbian sexual health service—clinically justified or politically correct? Br J Fam Plann. 1999;25:93–95. [PubMed]

- 18.Roberts SJ. Lesbian health research: a review and recommendations for future research. Health Care Women Int. 2001;22:537–552. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Brotman S, Ryan B, Cormier R. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):192–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Saulnier CF. Deciding who to see: lesbians discuss their preferences in health and mental health care providers. Soc Work. 2002;47(4):355–365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Fish J, Anthony D. UK national lesbians and health care survey. Women Health. 2005;41(3):27–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ferris DG, Batish S, Wright TC, Cusing C, Scott EH. A neglected lesbian health concern: cervical neoplasm. J Fam Pract. 1996;43(6):581–584. [PubMed]

- 23.Carroll NM. Optimal gynecologic and obstetric care for lesbians. Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 93:611–613. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Agnew C, Loving T. The role of social desirability in self-reported condom use attitudes and intentions. AIDS Behav. 1998;2(3):229–239. [DOI]

- 25.Nelson DE, Holtaman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, KAM. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46(Suppl 1):S3–S42. [PubMed]

- 26.Bowlin SJ, Morril BD, Nafziger AN, Jenkins PL, Lewis C, Pearson TA. Validity of cardiovascular disease risk factors assessed by telephone survey: the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(6):561–571. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. National Cancer Advisory Board Issues Mammography Screening Recommendations. Available at: http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/mar97/nci-27b.htm. Accessed October, 2005.

- 28.National Guideline Clearinghouse. Cervical cancer: Screening recommendations, with algorithms, for managing women with abnormal Pap test results. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?view_id=1&doc_id=7011. Accessed October 2005.

- 29.Foti E, Mancuso S. Early breast cancer detection. Minerva Ginecol. 2005;57(3):269–292. [PubMed]

- 30.Leyden WA, Manos MM, Geiger AM, et al. Cervical cancer in women with comprehensive health care access: attributable factors in the screening process. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(9):675–683. [DOI] [PubMed]