Abstract

This review examines the pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Stimulants that increase alertness/reduce fatigue or activate the cardiovascular system can include drugs like ephedrine available in many over-the-counter medicines. Others such as amphetamines, cocaine and hallucinogenic drugs, available on prescription or illegally, can modify mood. A total of 62 stimulants (61 chemical entities) are listed in the WADA List, prohibited in competition. Athletes may have stimulants in their body for one of three main reasons: inadvertent consumption in a propriety medicine; deliberate consumption for misuse as a recreational drug and deliberate consumption to enhance performance. The majority of stimulants on the list act on the monoaminergic systems: adrenergic (sympathetic, transmitter noradrenaline), dopaminergic (transmitter dopamine) and serotonergic (transmitter serotonin, 5-HT). Sympathomimetic describes agents, which mimic sympathetic responses, and dopaminomimetic and serotoninomimetic can be used to describe actions on the dopamine and serotonin systems. However, many agents act to mimic more than one of these monoamines, so that a collective term of monoaminomimetic may be useful. Monoaminomimietic actions of stimulants can include blockade of re-uptake of neurotransmitter, indirect release of neurotransmitter, direct activation of monoaminergic receptors. Many of the stimulants are amphetamines or amphetamine derivatives, including agents with abuse potential as recreational drugs. A number of agents are metabolized to amphetamine or metamphetamine. In addition to the monoaminomimetic agents, a small number of agents with different modes of action are on the list. A number of commonly used stimulants are not considered as Prohibited Substances.

Keywords: stimulants, monoaminergic agonists, re-uptake inhibitors, noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin, respiratory stimulant

Introduction

This review looks at stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) from the viewpoint of Pharmacology, or at least of a pharmacologist. The WADA stimulants list has not been compiled primarily with consideration of pharmacology, so that a pharmacological classification of the list is now attempted and such a classification would allow for a rational extension of the list to include compounds of similar properties.

A stimulant can be seen as a general term in dealing with the properties of drugs. We can think of cardiac stimulants, respiratory stimulants, central stimulants and so on. Hence, a stimulant can be seen as any agent that enhances function, perhaps an agent which mimics the actions of an excitatory neurotransmitter or antagonizes the actions of an inhibitory neurotransmitter. However, in the context of sport, the word stimulant usually refers to agents stimulating the central nervous system (CNS), affecting mood, alertness, locomotion and appetite, or targeting the sympathetic nervous system causing particularly cardiovascular actions. The well-known fight-or-flight reaction to increase blood flow to skeletal muscle and mobilize energy is a sympathetic response, which can be mimicked by stimulant drugs. The US Anti-Doping Agency defines a stimulant as ‘An agent, especially a chemical agent such as caffeine, that temporarily arouses or accelerates physiological or organic activity' (USADA, 2007).

Stimulants can include drugs that increase alertness/reduce fatigue, such as coffee or the major ingredient caffeine, or drugs like ephedrine available in many over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Others such as amphetamines, cocaine and hallucinogenic drugs can affect mood and modify mental alertness. Stimulants can have precise clinical indications such as narcolepsy, attention deficit or appetite suppression, or even nasal decongestion. However, many stimulants have potential for abuse, and are thus carefully controlled in many jurisdictions. In terms of sport, stimulants can provide an unfair advantage: increased alertness and diminished fatigue and cardiovascular activation can be advantageous in many events.

Why do athletes take stimulants?

Athletes may have stimulants in their body for one of three main reasons:

Inadvertent (or alleged inadvertent) consumption in a propriety medicine;

Deliberate consumption for misuse as a recreational drug;

Deliberate consumption to enhance performance.

Stimulants may be taken to increase alertness or convey some psychological motivational or attitude advantage from central actions. Peripheral actions may increase performance at least in the early stage of exercise by increasing cardiac output, increasing blood flow to muscles and by mobilizing energy. A warm-up prior to strenuous exercise results in increased blood flow to the exercising muscle and to cardiac muscle, warming of the body by transferring heat from the exercising muscles into the bloodstream, a warming that will also aid oxygen uptake by the tissues (oxygen dissociation curve for haemoglobin shifts to the right), and sweating for temperature regulation. Some or all of these effects can be mirrored by agents, which stimulate the cardiovascular system and particularly the heart. Sympathomimetic agents will mimic, to varying degrees, the fight-or-flight reaction. In particular, agents with β1-adrenoceptor stimulant actions would have cardiac stimulant effects. This would be especially important, perhaps not in increasing maximum level of cardiac output in exercise, but in increasing the rate of attaining a maximum level. However, the superiority of drug induced ‘warm-up' over an exercise warm-up is unclear. Further information on the possible performance enhancing effects of some stimulants in relation to adrenoceptors is included in Davis et al. (2008).

Do stimulants confer an advantage on a doped athlete? Clearly some athletes do think so: cardiac stimulant actions, increased alertness, decreased fatigue. However, the risks, in terms both of wellbeing and detection, far outweigh the perceived benefits.

Regulations concerning stimulants

Stimulants are banned only in competition, as any advantage they give is transient in nature, and as a total ban would be difficult given that many OTC medicines contain stimulants in addition to the stimulants obtainable as prescription medicines. It is not the intention of this review to discuss the criteria for deciding whether a drug detected in sport is a legitimate prescription or OTC medicine or a deliberate stimulant. Some general points can be noted as to how samples are interpreted. Prescription metanephrine is available usually as the d-isomer, so that the presence of both isomers would be inconsistent with prescription medicine (Cody, 2002). Besides a potentially legal prescription of amphetamines, many substances metabolize to methamphetamine or amphetamine in the body, including amphetaminil, benzphetamine, clobenzorex, deprenyl, dimethylamphetamine, ethylamphetamine, famprofazone, fencamine, fenethylline, fenproporex, furfenorex, mefenorex, mesocarb and prenylamine and selegiline (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002). Hence, relative concentrations of metabolites in the urine are relevant while deciding the source of the drug (Cody, 2002).

Agents specifically listed on the Prohibited List are shown in Table 1. However, the list ends with the catch-all statement ‘and other substances with a similar chemical structure or similar biological effects' (WADA, 2007). Some of those on the Prohibited List are ‘Specified Substances', and these are listed in column 2 of Table 1. Rather than interpreting the meaning of the term specified substance, I quote the explanation (the Italics are in the original):

Table 1.

Stimulants prohibited in competition

| Name | Specified substancea | Metabolized to A/Mb | Mode of actionc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrafinil adrenalined | Monoamine | ||

| Amfepramone | Monoamine | ||

| Amiphenazole | Resp. stim. | ||

| Amphetamine | Monoamine | ||

| Amphetaminil | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Benzphetamine | Yes M | Monoamine | |

| Benzylpiperazine | Monoamine | ||

| Bromantan | Monoamine | ||

| Cathined | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Clobenzorex | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Cocaine | Monoamine | ||

| Cropropamide | Yes | Resp. stim. | |

| Crotetamide | Yes | Resp. stim. | |

| Cyclazodone | Monoamine | ||

| Dimethylamphetamine | Yes M | Monoamine | |

| Ephedrined | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Etamivan | Yes | Resp. stim. | |

| Etilamphetamine | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Etilefrine | Monoamine | ||

| Famprofazone | Yes | Yes M | Analgesic |

| Fenbutrazate | Monoamine | ||

| Fencamfamin | Monoamine | ||

| Fencamine | Yes M | Monoamine | |

| Fenetylline | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Fenfluramine | Monoamine | ||

| Fenproporex | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Furfenorex | Yes M | Monoamine | |

| Heptaminol | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Isometheptene | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Levmethamfetamine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Meclofenoxate | Yes | Nootropic | |

| Mefenorex | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Mephentermine | Monoamine | ||

| Mesocarb | Yes A | Monoamine | |

| Methamphetamine (D-) | Yes Ae | Monoamine | |

| Methylenedioxyamphetamine | Monoamine | ||

| Methylenedioxymethamphet. | Monoamine | ||

| Pmethylamphetamine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Methylephedrined | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Methylphenidate | Monoamine | ||

| Modafinil | Monoamine | ||

| Nikethamide | Yes | Resp. stim. | |

| Norfenefrine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Norfenfluramine | Monoamine | ||

| Octopamine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Ortetamine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Oxilofrine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Parahydroxyamphetamine | Notef | Monoamine | |

| Pemoline | |||

| Pentetrazol | Resp. stim./GABA | ||

| Phendimetrazine | Monoamine | ||

| Phenmetrazine | Monoamine | ||

| Phenpromethamine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Phentermine | Monoamine | ||

| 4-Phenylpiracetam (carphedon) | Nootropic | ||

| Prolintane | Monoamine | ||

| Propylhexedrine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Selegiline | Yes | Yes | MAOI |

| Sibutramine | Yes | Monoamine | |

| Strychnine | Glycine | ||

| Tuaminoheptane and other substances with a similar chemical structure or similar biological effect(s) | Yes | Monoamine |

Abbreviations: GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Adapted from WADA (2007).

Specified substances: see text.

Metabolized to amphetamine/metamphetamine. List of substances metabolized to amphetamine (A) or metamphetamine (M) may be incomplete.

Codes for modes of action: GABA, GABA antagonist; glycine, glycine antagonist; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; monoamine, acts on monoaminergic systems (NA, DA or 5-HT); nootropic, nootropic actions; Resp. stim., respiratory stimulant.

See text for exceptions involving these agents.

Since methamphetamine metabolizes to amphetamine, all drugs, which metabolise to methamphetamine, will also produce amphetamine as a metabolite.

A metabolite of amphetamine.

‘The Prohibited List may identify specified substances, which are particularly susceptible to unintentional anti-doping rule violations because of their general availability in medicinal products or are less likely to be successfully abused as doping agents.' A doping violation involving such substances may result in a reduced sanction provided that the ‘…Athlete can establish that the Use of such a specified substance was not intended to enhance sport performance…' (WADA, 2007).

This would seem to suggest that there are two classes of offence, but I will not interpret this further. Some agents (cathine, ephedrine and methylephedrine) are prohibited only above a certain level in the urine sample. Adrenaline is not prohibited with local anaesthetics or when given locally for ocular or nasal use, for example. Likewise, imidazole derivatives are allowed for topical use, for example, as nasal decongestants. The USADA (2007) has the term Restricted Substance: ‘A prohibited substance that is permitted under certain circumstances. An athlete must notify the relevant medical authorities and provide US Anti-Doping Agency a statement from their physician'.

In addition, a number of stimulant substances are not considered as Prohibited Substances (but are subject to monitoring). These are as follows:

Bupropion: This is a weak antidepressant, acting as a weak blocker of monoamine re-uptake (Tardieu et al., 2004), and is widely available for the treatment of tobacco dependence (Hays and Ebbert, 2003).

Caffeine: Since caffeine is present in coffee and in many OTC medicines (Sweetman, 2007), it would be difficult to enforce a total ban on caffeine.

Phenylephrine: This is a direct sympathomimetic (see below) at α1-adrenoceptors causing vasoconstriction, and only very limited effects on the CNS. Phenylephine is widely used for topical use in the eye and as a nasal decongestant, and again is present in many OTC cold remedies (Sweetman, 2007).

Phenylpropanolamine: An indirect sympathomimetic (see below) that is present in many OTC medicines (Sweetman, 2007). See also Davis et al. (2008)

Pipradol (pipradrol): This is defined as a CNS stimulant (Sweetman, 2007) and is available in multi-ingredient preparations for fatigue. This agent has been available for more than 50 years, with reported actions as a dopamine (DA)-releasing dopaminomimetic (White and Hiroi, 1992; Kelley et al, 1997).

Pseudoephedrine: This is widely used in OTC medicines as a nasal decongestant/cold remedy (Sweetman, 2007) See also Davis et al. (2008).

synephrine (p-synephrine, oxedrine). An agent related to phenylephrine (m-synephrine). This is a vasoconstrictor and is also used for ocular purposes (Sweetman, 2007).

Why are agents on the Prohibited List?

How do drugs get on the Prohibited List? A new list is published every year in response to the recommendations of the List Committee (WADA, 2007). One can say that it is largely reactive, in response to what is available and what is found in urine samples, but the onus is on the athlete to prove that they have a legitimate reason for a medication.

A total of 62 stimulants (61 chemical entities) are listed in the World Anti-Doping List (Table 1). Many of these compounds are old agents, with research going back to the 1950s and 1960s, long before modern techniques and knowledge of receptor subtypes. Hence, a major problem in attempting to classify these drugs pharmacologically is that many of them were developed prior to ligand receptor-binding studies, or even functional studies on receptor subtypes, so that information available is at best patchy. While some of these agents are well-known pharmacological agents with established pharmacology, others are so obscure that they are more readily accessible through Google and the ‘amateur' pharmacological community rather than PubMed. Some are currently available clinically, some withdrawn and others have never been approved.

Spelling of chemical names is inconsistent on the list. Standard English spellings of chemical names are applied for some compounds, admittedly with inconsistency between use of ‘ph' and ‘f', but for other compounds, non-English spellings such as ‘etilamphentamine' are employed. It would seem more consistent to have a standard English list with additional names for alternative spellings.

Most are on the list because they are stimulants and may enhance performance, at least in certain events, but others like selegiline appear to be present for other reasons. Although the list is not meant to be definitive, some major omissions are obvious. There is no mention of methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) (the recreational drug ‘Eve'), although both methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) are listed, and also not of cathinone (widely consumed in Khat in the Horn of Africa), although cathine (also from Khat) is listed.

Clinical indications of stimulants

Stimulants are available for a number of indications, based on their peripheral and central actions.

Peripheral indications

Nasal decongestants

The mode of action is α1-adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction in the nasal mucosa, reducing mucosal swelling/mass to reduce congestion.

Treatment of hypotension by β-adrenoceptor-mediated cardiac stimulation and α1-adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction.

Positive inotropic actions

Cardiac stimulation by β-adrenoceptor agonism to increase the force of contraction and thus increase stroke volume.

Ocular actions

α1-Adrenoceptor agonists act to dilate the pupil by contracting the dilator pupillae muscle, and have actions to reduce intraocular pressure.

Central indications

Appetite suppression

Stimulants, and in particular amphetamines, are not generally recommended for weight loss (Sweetman, 2007). Appetite suppressants produce only moderate weight loss (Li et al., 2005). Actions may involve 5-HT2C-receptor activation (Wang and Chehab, 2006).

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Drugs like ritalin (methylphenidate): Actions may involve 5-HT2C-receptor stimulation (Rothman and Baumann, 2002). Recent evidence suggests that short-term benefit of ritalin in treatment of ADHD is not reflected in a long-term benefit at 3 years (Jensen et al., 2007).

Other central indications

Narcolepsy, fatigue and treatment of morphine addiction.

Pharmacological classes of stimulant

The list of prohibited agents is shown in Table 1. While some important widely used agents (both OTC/prescription and illegal) are present, the majority of substances tend to be older compounds little used clinically, and some with uncertain mechanisms of action.

The majority of stimulants on the list act on the monoaminergic systems: adrenergic (sympathetic, transmitter noradrenaline (NA)), dopaminergic (transmitter DA) and serotonergic (transmitter serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin (5-HT)). Sympathomimetic is a term used to describe agents that mimic sympathetic, or more correctly adrenergic responses, and the less commonly used phrases dopaminomimetic and serotoninomimetic could be used to describe actions on the DA and serotonin systems. However, many agents act to mimic more than one of these monoamines, so that a collective term of monoaminomimetic may be useful for the purpose of this review.

Smaller groups of agents on the list include respiratory stimulants, nootropic agents (agents, which may improve cognitive function) and monoamine oxidase (MAO).

Monoaminomimetic agents

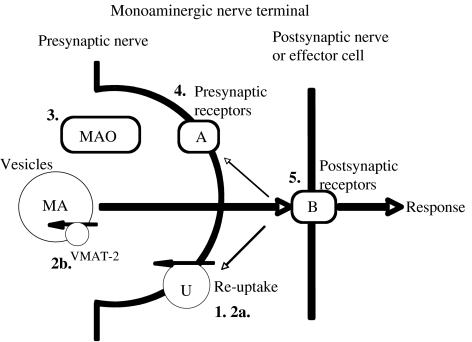

Since the vast majority of stimulants on the Prohibited List have actions involving the monoaminergic systems, the pharmacological actions of this wide class of agents are examined in detail. Sites of action of monoaminomimetic agents at monoaminergic synapses (CNS) and neuroeffector junctions (periphery) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sites of drug action at monoaminergic synapses. (1) Monoamine re-uptake inhibition, either non-selective inhibition or selective re-uptake inhibition of NA (selective NA re-uptake inhibitor), DA (SDRI) or 5-HT (serotonin)(serotonin re-uptake inhibitor). (2) Indirect monoaminomimetic actions, by action as substrate for monoamine re-uptake transporters (2a) or as a substrate for VMAT-2 (2b) to release (displace) monoamine (MA) neurotransmitter. (3) Inhibition of MAO. This is not a major site of action of stimulants (see text). (4) Stimulation (or block) of presynaptic inhibitory autoreceptors (that is, receptors for that neurotransmitter) or heteroceptors (that is, receptors for another transmitter) (A). Receptors can also be facilitatory. (5) Stimulation (or block) of postsynaptic receptors (B). These may be adrenergic, dopaminergic or serotonergic receptors. There may be more than one subtype of postsynaptic receptor so that the drug may behave differently from the monoamine neurotransmitter by selective actions at certain receptors. 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin; MAO, monoamine oxidase; VMAT, vesicular monoamine transporter.

Modes of action of stimulants include (often overlapping) (1) block of re-uptake of NA, DA and/or serotonin; (2) release of these monoamines; (3) MAO inhibition; (4) stimulation (direct or indirect, see below) of receptors for monoamines at presynaptic sites of nerve terminals and (5) stimulation (direct or indirect, see below) of receptors for monoamines at postsynaptic sites; or a combination of these effects. Amphetamines, cocaine and many other agents fit into these categories. In addition, differences between agents having mainly peripheral actions and those easily penetrating the CNS mean that some sympathomimetics can be used for peripheral actions, such as nasal decongestants, or for ocular use. Others have been used for their central actions as weight-loss medications and so on.

Noradrenaline, like adrenaline and some other monoaminomimetic agents, does not reach pharmacologically effective concentrations when given orally, due to metabolism by MAO, and to a lesser extent, due to catechol-O-methyltransferase in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Whereas adrenaline is absorbed slowly when given by subcutaneous and intramuscular injection, despite some vasoconstriction at the site of injection, the more marked vasoconstrictor effects produced by NA result in poor absorption. Incidentally, NA is also missing from the WADA list. Given that NA is a vasoconstrictor, which will raise blood pressure, with little effect on the heart, this combination of effects is unlikely to be of performance enhancing value. In addition, catecholamines have poor access to the CNS. Noncatecholamines, and especially non-monoamines, tend to be effective when given orally, due to relative or complete resistance to MAO, and many readily enter the CNS.

Monoamine re-uptake inhibition

A major site of stimulant action is the monoamine re-uptake transporter (see Figure 1). It has long been known that uptake of neurotransmitter into nerves is a two-step process involving, first, the monoamine re-uptake transporter across the nerve membrane, which is blocked by cocaine (Trendelenburg, 1966; 2a in Figure 1); and, second, uptake into the storage vesicle (now termed vesicular monoamine transporter, VMAT-2) (2b in Figure 1). Hence, pretreatment with reserpine (which depletes vesicles by interaction with VMAT-2; Partilla et al., 2006) does not prevent uptake of NA into nerves, but inhibits its storage in the vesicles, so that it is exposed to MAO and metabolized (Lindmar and Muscholl, 1964).

The neurotransmitter transporters for NA, DA and serotonin are closely related. NA and DA transporters have 80% similarity and both have higher affinity for DA, but differ in their sensitivity to blocking agents (Roubert et al., 2001). Although selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and NA re-uptake inhibitors, or combined serotonin and NA re-uptake inhibitors, (selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor/selective NA re-uptake inhibitor) have been used to treat depression, it has been suggested that a drug inhibiting all three transporters (that is, including the DA transporter) (perhaps a selective monoamine re-uptake inhibitor) may produce a more rapid onset of action and possess greater efficacy than traditional antidepressants (Chen and Skolnick, 2007).

Release of monoamines

Direct and indirect sympathomimetic (or monoaminomimetic)

A direct sympathomimetic is an agonist that directly activates adrenoceptors. Some agents, such as the endogenous neurohormone adrenaline, may be non-selective and act on all subtypes of α- and β-adrenoceptors. Other direct agonists may act only on α or β-adrenoceptors, or even only on subtypes of these. Direct β2-adrenoceptor agonists do not come under the stimulants section, but are covered in the asthma section of the WADA lists, although a number of stimulants have actions at β2-adrenoceptors in addition to other actions (for example, ephedrine). Figure 1 shows sites of actions of drugs at a monoaminergic synapse (CNS) or neuroeffector junction (periphery).

An indirect sympathomimetic does not act directly at adrenoceptors, but induces release of NA from nerve terminals, and the NA then acts on the adrenoceptors. Classical agents, like tyramine, act mainly indirectly, resulting in both α and β-adrenoceptor stimulation. In addition to the synaptic monoamine transporter mediating entry of monoamines into the nerve terminal, there is a vesicular transporter that, in the case of adrenergic nerves, transports DA and NA into synaptic vesices (Fleckenstein et al., 2007). Tyramine acts on the VMAT-2 (2b in Figure 1; Vaccari, 1993; Fleckenstein and Hanson, 2003). We must distinguish the actions of tyramine that enters the nerve through the NA uptake system and directly displaces NA from vesicles from the actions of agents like cocaine that block the re-uptake system. Tyramine causes release of small amounts of noradrenaline unrelated to nerve activity, whereas cocaine potentiates nerve-mediated responses by increasing the synaptic concentration of NA during nerve activity. The foregoing comments could equally well apply to indirect dopaminomimietics and serotonomimietics (Figure 1).

The identification of an agent as a direct or indirect sympathomimetic (or monoaminomimetic) is not as easy as it might seem. Ephedrine, long thought of as an indirect sympathomimetic, with debate going back more than 50 years as to its indirect (Fleckenstein and Burn, 1953) or direct (Krogsgaard, 1956) modes of action, has recently been definitively shown to be mainly a direct sympathominmetic using a DA-β-hydroxylase-knockout mouse model (Docherty, 2007; Liles et al., 2007). Agents specifically targeting one type of adrenoceptor, for example, α-adrenoceptors, are less likely to be indirect sympathomimetics, whereas agents with actions on both subtypes are more likely to be indirect sympathomimetics (that is, if an agent releases NA, the released NA should act on both α and β-adrenoceptors). Of course, drugs can also displace DA or 5-HT from nerve terminals and/or block the re-uptake of these monoamines in the same way as for NA. Figure 1 shows the sites of actions of drugs at monoaminergic synapses.

Some agents also compete for and effectively block NA re-uptake because of their high affinity for the re-uptake system. The exchange diffusion model predicts that as drugs act as substrates for the re-uptake transporter, they enter the nerve terminal where they cause transporter-mediated release of neurotransmitter. The inhibition of uptake is then due to competition with the neurotransmitter for the carrier, and also because the carrier is functioning in reverse to release neurotransmitter (Crespi et al., 1997; Fleckenstein et al., 2007). Many agents, such as methamphetamine, also act on the VMAT in a similar manner (Fleckenstein et al., 2007). Interference with VMAT-2, for example, by metamphetamine, results in increased cytoplasmic levels of monoamines, causing damage from auto-oxidation (Brown et al., 2000).

Hence, there are two related mechanisms where neurotransmitter can be displaced: involving the vesicular transporter VMAT-2 (2b) or the synaptic re-uptake transporter (2a) (Figure 1). There is also evidence that re-uptake blockers, such as cocaine, in high concentration may also displace NA, as cocaine produces a tachycardia in the absence of nerve activity (Docherty and McGrath, 1980).

MAO inhibition

Another site of monoaminomimietic action at the monoamine synapse is the enzyme MAO (see Figure 1). The adrenergic, and indeed dopaminergic and serotonergic, systems have no enzyme that can rapidly terminate transmitter responses in a manner analogous to acetylcholinesterase in the cholinergic system. However, MAO, which deaminates many amines (for example, tyramine, NA, DA), is widely distributed in the body, occurring mainly in mitochondria, including those in monoaminergic nerve terminals (Blaschko et al., 1937). Axelrod (1957) showed presence in rat liver of the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase, which metabolizes NA to normetanephrine. MAO mainly regulates the intraneuronal concentration of monoamines, whereas catechol-O-methyltransferase regulates extraneuronal and circulating catecholamines, so that catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition, but not MAO inhibition, has been shown to increase pressor responses to NA (Docherty and McGrath, 1980; Figure 1). However neither of these enzymes is critical in the termination of the action of NA acutely. Inhibition of MAO has no effect on the action of NA acutely (Hertting et al., 1961). Acute inhibition of MAO-B in the rat does not affect striatal DA metabolism, but chronic MAO-B inhibition increases release of striatal DA (Lamensdorf et al., 1996). For this reason, inhibitors of MAO are unlikely to be stimulants when given acutely. MAO inhibitors used in the treatment of depression normally take weeks to produce clear effects.

Older, non-selective MAO inhibitor drugs such as tranylcypromine resulted in hypertensive crisis when dietary amines, such as tyramine, were ingested, as these amines are normally metabolized in the gut by MAO (Volz and Gleiter, 1998). Even for agents not substrates for MAO, its inhibition will increase the effect of any NA displaced. Selective MAO-B inhibitors, such as selegiline, reduce or avoid this possible interaction. Selegiline is the one MAO inhibitor on the list, but selegiline is there because methamphetamine and amphetamine are metabolites (Nishida et al., 2006).

Presynaptic/pre-junctional receptors

Drugs can also act on subtypes of monoaminergic receptor either pre- or post-junctionally at the synapse (Figure 1). Let us look at presynaptic (pre-junctional) receptors first.

These receptors are predominantly inhibitory in nature. α2-Adrenoceptors of both the 2A and 2C subtypes are present on noradrenergic (or other) nerves and mediate a negative feedback inhibition at adrenergic nerves (autoreceptors) or inhibition at other nerves (heteroceptors) (Starke, 1977; Docherty, 1980). In addition, inhibitory presynaptic dopaminergic and serotonergic are present as autoreceptors at their respective neurons and as heteroceptors on other nerves. Amphetamine derivatives, such as MDA, MDEA, MDMA and cathinone, have actions at inhibitory α2-adrenoceptors to reduce nerve activity evoked release of NA (Lavelle et al., 1999; Rajamani et al., 2001), but this action may be less important than effects on re-uptake transporters. However, direct actions at pre-junctional receptors may alter the profile of action of a monoaminomimetic (for example, modafinil has been reported to inhibit dopaminergic neurons by direct agonism at presynaptic DA D2 receptors; Korotkova et al., 2007).

Postsynaptic receptors

In addition, monoaminomimietic drugs can activate subtypes of receptor for NA, DA or 5-HT postsynaptically (see Figure 1). If stimulant drugs all acted as indirect monoaminomimietics, then differences between drugs would be confined to relative efficacies at releasing each of the three monoamines. However, many stimulant drugs have additional (or exclusive) direct actions at subtypes of receptor, and these direct actions can explain major differences in types of stimulant action. Even considering adrenergic synapses, there are a large number of possible postsynaptic receptors as targets for sympathomimietic agonists, α1A, α1B, α1D, α2A, α2B and α2C, and this does not even consider β-adrenoceptors. In addition, there are multiple subtypes of DA receptors and especially 5-HT receptors, allowing complex interactions between drugs and monoaminergic systems. 5-HT2C (formerly termed 5-HT1C) receptors, possibly in the hypothalamic appetite centre, may be involved in decreasing appetite, as demonstrated in knockout mouse models (Wang and Chehab, 2006), and it has been suggested that fenfluramine and other anti-appetite agents act at 5-HT2C receptors (Bickerdike et al., 1999). Both 5-HT2C receptor and α2A-adrenoceptor are candidate genes for weight gain in patients on antipsychotics (Müller and Kennedy, 2006). Agonists at 5-HT2C receptors may also be useful in attention deficit and depression. Fluoxetine (prozac), in addition to serotonin re-uptake transporter blockade (Wong et al., 1975), has high affinity for 5-HT2C receptors (Sanchez and Hyttel, 1999). The 5-HT2A (Aghajanian and Marek, 1999), and possibly other 5-HT2 receptors (Nelson et al., 1999), may mediate some of the hallucinogenic actions of drugs like LSD (LSD shows potency as a partial agonist particularly at 5HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors: Porter et al., 1999). Cardiac valvular fibroplasic actions of fenfluramine, phentermine and ergot (Connolly et al., 1997) may involve 5-HT2B receptors (Fitzgerald et al., 2000), and MDMA and MDA may have similar actions by 5-HT2B stimulation (Setola et al., 2003). Mice lacking the 5-HT re-uptake transporter gene develop valvular hyperplasia, suggesting that the 5-HT transporter normally functions to reduce levels of 5-HT and reduce 5-HT receptor stimulation (Mekontso-Dessap et al., 2006). Amphetamine derivatives, particularly MDMA, in addition to actions at serotonergic and dopaminergic systems, can have direct agonist actions at both α1- and α2-adrenoceptors, and these actions contribute to cardiovascular and thermogenic side effects (Lavelle et al., 1999; Bexis and Docherty, 2006; Figure 1).

5-Hydroxytryptamine, serotonin, is known to be involved in thermoregulation; microinjection of 5-HT into the hypothalamus increases temperature in rats, whereas 5-HT2-receptor agonists increase and 5-HT1-receptor agonists decrease temperature (Lin et al., 1998). Dopamine-receptor antagonists also decrease the temperature actions of MDMA (Hewitt and Green, 1994; Mechan et al., 2002), and 5-HT2-receptor antagonists induce hypothermia (Fantegrossi et al., 2003). In our own studies, we found that α2A-adrenoceptor antagonism blocked early component of the hyperthermia to MDMA in mice, and this early component of the hyperthermia to MDMA was absent in α2A-knockout mice, demonstrating conclusively that α2A-adrenoceptor were involved (Bexis and Docherty, 2005, 2006).

Hence, drugs may have a complex series of actions, both therapeutic and toxic, involving direct and indirect agonism, and re-uptake blockade at adrenergic, dopaminergic and serotonergic synapses. Presumably the sheer number of possible actions of a drug results in a great deal of individual variation in the effects of individual drugs. Given the complicated actions of drugs such as MDMA that have been widely studied, it is difficult to give a definitive mode of action for many of the agents that have not been widely studied, but I have tried to provide as much clear information as possible under the entry for each drug (see below).

Side effects of drugs

Whether used inadvertently in over the counter medicines, or taken deliberately to enhance performance or as recreational drugs, side effects can be serious. For stronger agents, such as the amphetamine derivatives and cocaine, quite apart from mood altering and addiction problems, there are sudden deaths from cardiovascular complications, thermoregulatory problems and so on. Cardiovascular complications have been best documented for cocaine, which has been shown (even on single usage) to increase the risk of sudden cardiac death more than 20-fold (Mittleman et al., 1999). This action of cocaine presumably involves blockade of the re-uptake of NA into cardiac nerve terminals, resulting in increased post-junctional effects of neurally released NA. MDMA has an effect similar to cocaine in potentiating the cardiac actions of NA, and this may also have implications in terms of the cardiac morbidity of MDMA (Al-Sahli et al., 2001).

Sudden cardiac death in young fit, healthy adults is rare and is usually due to a congenital cardiac abnormality leading to a fatal arrhythmia (Drezner, 2000), and there is increasing public awareness of this problem due to high-profile deaths. It is not clear whether fitness regimes or diet play a role, but whatever is the case the use, of cardiac stimulants are likely to increase the risk. As stimulants as a class are generally classified as sympathomimetics, a major source of side effects and indeed fatalities must be from cardiac actions. Even the endogenous hormone, adrenaline, can cause fatal arrhythmias.

Other drugs used as appetite suppressants acting on the serotonergic system may have unexpected side effects on the heart. Fenfluramine has been withdrawn due to morbidity and fatalities from actions on cardiac valves and in causing pulmonary hypertension. Both actions seem to be linked to the serotonergic actions of the drug.

A number of stimulants affect temperature control, notably amphetamine derivatives such as MDMA, and use in hot conditions, such as that occurring at ‘Raves', has led to many fatalities from the consequences of hyperthermia.

Compounds listed by mode of action

Table 1 lists compounds and their modes of action Monoaminomimetic

Adrafinil

It is chemically related to modafinil, and is given orally for mental function to the elderly, particularly in France (Sweetman, 2007). An α1-adrenoceptor agonist and central α1-adrenoeptor stimulant (Duteil et al., 1979; Simon et al., 1983).

Adrenaline (L-adrenaline; more active isomer)

Adrenaline with local anaesthetic or by local administration, for example, nasal, ocular, is not prohibited (WADA, 2007). It is a peripherally acting sympathomimetic (does not readily cross blood brain barrier), that is inactive orally due to first-pass metabolism and has a short duration of action due to re-uptake/metabolism. It is used with anti-histamine and steroid for hypersensitivity and anaphylactic reactions (Sweetman, 2007). Adverse effects, including anxiety, palpitations, tachycardia, salivation and cold extremities, can be expected due to its sympathomimetic action, stimulating both α- and β-adrenoceptors; in higher doses, it causes arrhythmias and hypertension. Indeed, adrenaline can be used to produce arrhythmias in animal models (Hashimoto, 2007). When used with local anaesthetics, there is a danger of gangrene of extremities due to strong local vasoconstriction. It finds ocular use for wide-angle, but not narrow-angle, glaucoma to reduce intraocular pressure (presumably by increasing outflow and/or reducing aqueous humor production, despite actions to dilate pupil; Hurvitz et al., 1991; Marquis and Whitson, 2005). Adrenaline is used as a vasoconstrictor in the hypotension of severe septic or cardiagenic shock or cardiac arrest (Zhong and Dorian, 2005), but it is unlikely to be relevant to use as an in-competition stimulant.

Amfepramone (diethylpropion)

A weight-loss medication for short-term treatment of obesity (Dixon, 2006). Its actions are similar to those of dexamphetamine and has the street name ‘blue' (Sweetman, 2007). A central stimulant and indirect sympathomimetic with α-adrenoceptor actions (Borsini et al., 1979), but its actions may also involve 5-HT1A-receptor agonism (Mello et al., 2005).

Amphetamine

Amphetamine has long been described as an indirectly acting sympathomimetic CNS stimulant (Sweetman, 2007), and has been proven to be a predominantly indirectly acting sympathomimietic in the mouse (Liles et al., 2007). Amphetamine has been used to treat narcolepsy and ADHD, but is no longer recommended as an anorexic. It is a potent releaser of NA and DA, but not 5-HT (Wee et al., 2005). See also Davis et al. (2008).

Amphetaminil (amfetaminil)

An N-alkyl amphetamine derivative, it is metabolized to amphetamine (Cody, 2002). A central stimulant that is given orally to treat narcolepsy (Sweetman, 2007).

Benzphetamine

A central stimulant and sympathomimietic with actions similar to dexamphetamine that has been used as anti-obesity drug (Sweetman, 2007). It is metabolized to both to amphetamine and metamphetamine (Cody, 2002). It is used experimentally in cytochrome P450 studies.

Benzylpiperazine

This agent has behavioural effects similar to MDMA (Yarosh et al., 2007). It has monoaminomimetic actions, particularly at the 5-HT and DA transporters (Baumann et al., 2004), and may act preferentially on the 5-HT transporter. This agent is not covered by Sweetman (2007). It is used as a recreational drug of abuse (Gee et al., 2005), and its dopaminergic actions result in hyperactivity (Brennan et al., 2007).

Bromantan (bromantane)

This is a stimulant developed in Russia (most references to the agent are in Russian). There were positive tests for bromantan in both the Atlanta and Sydney Olympics. It is reported to have serotonergic and dopaminergic, and to a lesser extent also has noradrenergic actions (Kudrin et al., 1995; Morozov et al., 2000). Its peripheral sympathomimetic actions may increase stroke volume (Morozov et al., 2000). Its cholinergic toxicity has been reported in higher doses (Bugaeva et al., 2000). The effects are reported to be similar to those of mesocarb. It is not to be confused with bromatan, a preparation containing the anti-histamine brompheniramine, the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine and the opioid dextramethorphan (Sweetman, 2007).

Cathine (d-norpseudoephedrine)

Usage of cathine is prohibited if its concentration in the urine exceeds 5 μg mL−1 (WADA, 2007). From Khat, it is used as an anorectic. The more active ingredient from Khat, cathinone (Kalix, 1992), is not specified in the list as a prohibited drug (other than by the catch-all phrase), but the stimulant properties of Khat are mainly due to cathinone, which has amphetamine-like actions and can cause dependence (Kalix, 1992; Sweetman, 2007). See also Davis et al. (2008).

Clobenzorex

This is a central stimulant and sympathomimetic (Sweetman, 2007) used as an anti-obesity drug; an n-substituted amphetamine, which is metabolized to amphethamine, which could result in a positive test (Cody, 2002). Its actions are like those of dexamphetamine (Young et al., 1997) and has been used as a drug of abuse (Baumevieille et al., 1997). It is reported to have been used by athletes and baseball players to decrease fatigue, increase attention and reduce reaction time.

Cocaine

It is an uptake blocker for monoamines. Cocaine abuse is widespread. Topical use can cause corneal damage, and nasal inhalation may cause damage to nasal septum with prolonged use, both presumably due to actions as a vasoconstrictor by an indirect sympathomimetic action (Smith et al., 2002). Even a single dose of cocaine has been shown to increase the risk of sudden cardiac death more than 20-fold (Mittleman et al., 1999). Cocaine can cause dependence, but there is no major withdrawal syndrome, although acute withdrawal can cause anxiety, depression and exhaustion (Glauser and Queen, 2007). Cocaine use is also associated with violence and murder (Glauser and Queen, 2007). Cocaine's use as a local anaesthetic is now largely restricted to ENT surgery due to its ocular side effects.

Cyclazodone (cyclexanone; 2-(cyclopropylamino)-5-phenyl-1,3-oxazol-4-one (PubChem)

Cyclopropylpemoline (source, PubChem) is not listed in Sweetman (2007). It is a derivative of pemoline, which has stimulant actions similar to the effects of dexamphetamine (Segal et al., 1967).

Dimethylamphetamine (dimetamfetamine)

This is a CNS stimulant, often sold as drug of abuse on the streets as metamphetamine. It is metabolized to metamphetamine (Cody, 2002). It is no longer actively marketed (Sweetman, 2007).

Ephedrine

Ephedrine is prohibited if its concentration in the urine exceeds 10 μg mL−1 (WADA, 2007). This is a natural alkaloid (amine) similar in structure to amphetamine; used as stimulant, appetite suppressant and decongestant (Sweetman, 2007). Long thought to have both direct, but mainly indirect, α and β-adrenoceptor actions, it acts like a long acting adrenaline and raises blood pressure by cardiac stimulation and vasoconstriction, but with central actions. However, recent evidence suggests that ephedrine is predominantly a direct agonist at the α- and β-adrenoceptors (Docherty, 2007; Liles et al., 2007). However, there is contradictory evidence that it does not stimulate human α1- or α2-adrenoceptors, but may be a weak antagonist at the α2-adrenceptors (Ma et al., 2007). At least, ephedrine does act directly at human β-adrenoceptors (Vansal and Feller, 1999). Toxicity can result from ingestion of ephedrine-containing dietary supplements (including Ephedra (ma-huang) in Chinese herbal medicine) or due to exceeding dosage of OTC ephedrine (Sweetman, 2007). Hypertension from ephedrine is due to its α-adrenoceptor effects, tachycardia and possible arrhythmias from β-adrenoceptor effect. See also Davis et al. (2008).

Etilamphetamine (ethylamphetamine)

A CNS stimulant with actions similar to dexamphetamine (Sweetman, 2007). It has been used as an anorexic, and is metabolized to amphetamine (Cody, 2002).

Etilefrine (ethylnorphenylephrine)

A direct-acting β1-adrenoceptor agonist (Karasawa et al., 1992) with some α- and β2-adrenoceptor actions (Coleman et al., 1975; Adigun and Fentem, 1984; Lippert et al., 1987; Sweetman, 2007). It has been used for treatment of hypotensive states by cardiac and pressor actions, and as a nasal decongestant (Sweetman, 2007). It has been used to treat priapism (prolonged penile erection) (Teloken et al., 2005) as has phenylephrine (Munarriz et al., 2006), both acting by α1-adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction.

Famprofazone

An analgesic/antipyretic (Sweetman, 2007), which may be on the list of stimulants, as it is present in Gewodin with caffeine, or more likely as it is metabolized to metamphetamine, which can lead to false positives in tests (Cody, 2002).

Fenbutrazate (phenbutrazate)

An older (going back 50 years) CNS stimulant and anti-obesity agent in the preparation Cafilon (Fitzgerald and McElearney, 1957; Sweetman, 2007). It is no longer available (Sweetman, 2007). It as an uncertain pharmacology, but Cafilon, which also contains phenmetrazine (Craddock, 1976), is reported to have sympathomimetic actions like those of dexamphetamine.

Fencamfamin (fencamfamine)

A CNS stimulant, which increases locomotor activity (Todd, 1967), and is used to treat narcolepsy, for example. Displays sympathomimetic side effects (Shindler et al., 1985), and indirect DA agonist actions, with effects on the DA transporter (Seyfried, 1983; Li et al., 2006), which may explain its locomotor effects. Fencamfamin was the most frequently detected stimulant in South African dope testing between 1986 and 1991 (Van der Merwe and Kruger, 1992).

Fencamine

A CNS stimulant and an amphetamine/caffeine derivative, it is metabolized to metampthetamine (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002). It has been used for depression (Quiros e Isla, 1970); it is not in Sweetman (2007).

Fenetylline

This is an amphetamine/theophylline derivative, which is metabolized to amphetamine and theophylline (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002), with actions as a CNS stimulant. It has been used for attention deficit, narcolepsy and depression. Its actions are reported to be similar to those of dexamphetamine, but perhaps has lesser side effects (Kristen et al., 1986).

Fenfluramine

This is an anti-obesity agent withdrawn in the United States in 1997 due to cardiac-valve abnormalities (30% of users may have abnormal valves) and pulmonary hypertension; both effects are linked to serotoninomimetic actions and valvular actions may involve 5HT2B-receptor activation (Roth, 2007). Fenfluramine interacts with monoamine transporters to release NA, DA and 5-HT (Rothman et al., 2003), and inhibits 5-HT re-uptake (Kannengiesser et al., 1976).

Fenproporex (N-2-cyanoethylamphetamine)

This is a CNS stimulant that has been used by long-distance truck drivers in Brazil (Silva et al., 1998). It is an indirect sympathomimetic, and has been used as anti-obesity agent. It is metabolized to amphetamine (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002).

Furfenorex

This is an anti-appetite amphetamine derivative, which is metabolized to metamphetamine (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002). It is not in Sweetman (2007). It is structurally similar to benzphetamine.

Heptaminol

This is a cardiac stimulant with predominantly positive inotropic actions (Berthiau et al., 1989), and also has a pressor effect in cats (Grobecker and Grobecker, 1976). It has been used to treat low blood pressure and orthostatic hypotension (Boismare and Boquet, 1975), with reported ‘unexpected' adverse effects (Pathak et al., 2005). Its actions may involve NA release by action at the transporter (Grobecker and Grobecker, 1976; Delicado et al., 1990), but it may also have effects on Ca2+ channels to increase intracellular calcium (Peineau et al., 1992). See also Isometheptene.

Isometheptene

This is a sympathomimietc vasoconstrictor sometimes used in migraine (in-preparation amidrine) (Sweetman, 2007). Actions involve indirect β- and α-adrenoceptor actions and direct α-adrenoceptor agonism (Valdivia et al., 2004). A minor metabolite can be converted to heptaminol under drug-screening procedures (Lyris et al., 2005).

Levmethamfetamine

This is the less active L-isomer (rather than the more active D-isomer) of metamphetamine that is less potent as a CNS stimulant. It is present in Vick's Vapor Inhaler (United States) (Sweetman, 2007).

Mefenorex

This is an indirect sympathomimetic CNS stimulant that has been used as an anorectic. It is an amphetamine derivative that is metabolized to amphetamine (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002). It is reported to have serotonergic actions (to release 5-HT) and, to a lesser extent, dopaminergic actions (Orosco et al., 1995).

Mephentermine

A sympathomimetic vasoconstrictor used to maintain blood pressure in hypotensive states (Kansal et al., 2005), with some CNS actions. It has been used as a nasal decongestant (Todd, 1967). It is reported to have α- and β-adrenoceptor stimulant actions, probably mainly indirect (Paton, 1975).

Mesocarb (sydnocarb)

This is a stimulant developed in Russia in the 1970s. It is reported to increase DA release (Afanas'ev et al., 2001) and increases locomotor actions due to DA-receptor stimulation (Witkin et al., 1999).

Methamphetamine (D-methylamphetamine, metamphetamine)

This is available for weight loss and ADHD (Sweetman, 2007). Since metamphetamine metabolizes to amphetamine, all drugs, which metabolize to metamphetamine, will also show lower levels of amphetamine. Methamphetamine as a drug of abuse has well-documented actions to produce hyperthermia and neurodegeneration (Sharma et al., 2007). In an attempt to control the illicit production of methamphetamine, many cold remedies have changed from pseudoephrine to the less effective nasal decongestant phenylephrine (Eccles, 2007).

Methylenedioxyamphetamine (tenamfetamine)

In addition to being subject to misuse per se, MDA is also a metabolite of MDMA and MDEA (Skrinska and Gock, 2005). See also Methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy, MDMA)

MDA and MDMA were synthesized in 1910 and 1912, respectively, but MDMA was not patented, as is popularly believed, as an appetite suppressant (Freudenmann et al., 2006). They first appeared as recreational drugs in the 1960s and became popular in the rave culture of the 1990s, with MDMA known as Ecstasy and the chemically similar ‘designer' compound MDEA as Eve. Incidentally, MDEA is not specifically prohibited in the WADA list (other than by the catch-all phrase). Users of these amphetamine derivatives report feelings of euphoria, excitement and warmth, emotionally (Mas et al., 1999). Pharmacological investigations reveal a wide range of actions for these agents. MDMA has affinity for serotonin-uptake sites, 5HT2 receptors, α2-adrenoceptors, muscarinic receptors, NA-uptake sites, α1-adrenoceptors and DA-uptake sites, 5-HT1 and DA receptors (largely in order of potency) (Battaglia et al., 1988; Cleary and Docherty, 2003). In terms of function, MDMA has been shown to act as an agonist at α2-adrenoceptors (Lavelle et al., 1999) and 5-HT2 receptors (Green et al., 2003). MDMA causes release of 5-HT from synapses (Nichols et al, 1982), and MDA and MDEA have similar effects (Schmidt et al., 1987). All three also induce release of DA from striatal slices (Schmidt, 1987). MDMA releases NA with higher potency than for serotonin or DA release (Rothman et al., 2001). MDMA also acts on the NA transporter in the heart to increase responses to NA, and this may be the basis of cardiac side effects (Cleary et al., 2002; Cleary and Docherty, 2003). Reported side effects of ring-substituted amphetamines include sweating, tender muscles, tachycardia, restlessness, and when the euphoric effects wear off, fatigue, insomnia, problems with mood and liveliness (Vollenweider et al., 1998; Milroy, 1999; Wilkins et al., 2003). In addition, there are serious toxic effects, with the first reported death linked to MDMA in 1987, and many deaths ever since (for example, 81 in England and Wales over 3 years; Schifano et al., 2003), characterized by hyperthermia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure, in addition to cardiovascular mortality (Dowling et al., 1987), long-term cardiovascular effects (Brody et al., 1998) and possible neurodegeneration (White et al., 1996). In human volunteers, MDMA increases blood pressure and causes palpitations (Vollenweider et al., 1998), and in rats, rises in blood pressure are linked to peripheral α1/α2-adrenoceptor and 5-HT2-receptor agonism (McDaid and Docherty, 2001).

p-Methylamphetamine (para-methylamphetamine)

It is not in Sweetman (2007). This is not an isomer of metamphetamine, but a derivative of amphetamine (with the methyl substitution on the ring: what is commonly called methamphetamine is actually n-methylamphetamine with the methyl on the nitrogen). Unlike D-amphetamine, which is a potent releaser of NA and DA but not 5-HT, p-methylamphetamine is approximately equipotent at releasing all three amines and has lower potency as a reinforcer in an animal model (Wee et al., 2005).

Methylephedrine

Use of methylephedrine is prohibited if its concentration in the urine is above 10 μg mL−1 (WADA, 2007). This is a sympathomimetic agent like ephedrine, with α- and β-adrenoceptor actions. It has bronchodilator actions like ephedrine (Todd, 1967). However, recent evidence suggests that methylephedrine does not stimulate human α1- or α2-adrenoceptors, but may be a weak antagonist at α2-adrenceptors (Ma et al., 2007). It is present in cold remedies and as nasal decongestant.

Methylphenidate (Ritalin)

This agent is the major drug used to treat ADHD, and as such has an extremely detailed entry by Sweetman (2007). It is an NA and DA re-uptake inhibitor, which may lack the neurotoxic effects of amphetamine derivatives involving combined dopaminergic and serotonergic agonism (Reneman et al., 2001). α2-Adrenoceptor-, (Andrews and Lavin, 2006), DA D1- (Arnsten and Dudley, 2005) and DA D2-receptor stimulation (Bardin et al., 2007) have been reported for methylphenidate. Actions in ADHD may involve 5-HT2C-receptor stimulation (Rothman and Baumann, 2002). Recent evidence also suggests involvement of the α2A adrenoceptor gene with the methylphenidate-induced improvement in ADHD (Polanczyk et al., 2007). There is evidence that Ritalin may decrease growth in children (Faraone and Giefer, 2007).

Modafinil

This is a CNS stimulant chemically related to adrafinil that has been employed for narcolepsy, other sleep disorders (Sweetman, 2007) and ADHD (Lopez, 2006). It activates noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems to promote wakefulness (Boutrel and Koob, 2004), presumably by indirect actions at the relevant re-uptake transporters (Wisor et al., 2001), and has been misused as a drug to increase alertness (Sweetman, 2007). Modafinil has also been reported to inhibit dopaminergic neurons by direct agonism at presynaptic DA D2 receptors (Korotkova et al., 2007).

Norfenefrine (m-octopamine)

This agent is predominantly an α1-adrenoceptor agonist (Zimmer, 1997). Used as a vasopressor for hypotensive states (Sweetman, 2007).

Norfenfluramine

This is the major metabolite of fenfluramine. It interacts with transporters to release NA, DA and 5-HT (Rothman et al., 2003).

Octopamine (p-octopamine: discovered from octopus salivary gland)

Octopamine, like tyramine, is a monoamine neurotransmitter in invertebrates, but has an uncertain role in vertebrates (Roeder, 1999), and as such is a substrate for MAO (Schönfeld and Trendelenburg, 1989). A ‘false neurotransmitter' hypothesis with octopamine replacing NA as a relatively inactive transmitter has long been used to explain the orthostatic hypotension produced by chronic MAO inhibition (Kopin et al., 1965). However, the false transmitter theory has been questioned (Hicks et al., 1987) and a more complex mode of action of octopamine has emerged given that it is an endogenous agonist for the recently discovered trace-amine receptors (Zucchi et al., 2006; Grandy, 2007). It is reported by Sweetman (2007) to have predominantly α-adrenoceptor-agonist actions when used for treatment of hypotensive states, although trace-amine receptors must now also be considered. Octopamine produces pressor responses in vivo (Fujiwara et al., 1968), and vascular contractions in vitro (Hayashi and Park, 1984). A β-adrenoceptor-mediated depressor response is reported following α-adrenoceptor blockade (Fujiwara et al., 1968), and octopamine can additionally reduce blood pressure by a central action (Edwards, 1982). It is reported to stimulate β3-adrenoceptors to release fat from adipocytes (Visentin et al., 2001), and is also metabolized by MAO to produce an agent with insulin-like actions on glucose transport (Visentin et al., 2001); these actions may explain its use in weight loss remedies. Trace-amine receptors may be involved in some or all of the above actions. Many-weight loss supplements, containing amines such as octopamine, have been shown to raise blood pressure (Haller et al., 2005), with little evidence for weight loss.

Ortetamine (2-methyl-1-phenylpropran-2-amine)

According to PubChem, it is phentermine, but has nothing under its name other than being an anorexic. See Phentermine.

Oxilofrine (1-hydroxypholedrine diastereomer)

This is a sympathomimetic used to treat hypotensive states, with actions similar to those of ephedrine (Sweetman, 2007). Its actions may be largely indirect by releasing NA (Jacquot et al., 1980). It is reported to have predominantly cardiac inotropic actions (Kauert et al., 1988). It is a metabolite of p-methoxymethamphetamine.

Parahydroxyamphetamine

This is presumably a hydroxyamphetamine that is used in eye drops with tropicamide to dilate the pupil. It is a sympathomimetic with actions similar to those of ephedrine, but has very little CNS-stimulant actions (Sweetman, 2007). Hydroxyamphetamine has been used to diagnose Horner's syndrome due to a postganglionic lesion based on the assumption that it acts in the eye as an indirect syumpathomimetic (see for example, Skarf and Czarnecki, 1982). Parahydroxyamphetamine is a metabolite of amphetamine.

Pemoline

Pemoline has been withdrawn in many countries due to liver problems. It is a monoaminomimetic (predominantly DA; Nicholson and Pascoe, 1990) and has been used for ADHD (Sweetman, 2007). It is structurally different, but has actions similar to those of dexamphetamine and methylphenidate (Segal et al., 1967; Sweetman, 2007).

Phendimetrazine

This is an indirect sympathomimetic used as an anorectic. Its actions are similar to those of dexamphetamine. Metabolite is phenmetrazine, which may be the active drug (Rothman et al., 2002). Now rarely prescribed due to abuse potential, and fenfluramine-like cardiovascular side effects of pulmonary hypertension and cardiac-valve defects (Sweetman, 2007).

Phenmetrazine

This is a sympathomimetic anorectic now largely withdrawn (Sweetman, 2007). It was preferred to amphetamine by addicts in the 1950s and 1960s until it became unavailable. A metabolite of phendimetrazine, it interacts especially with noradrenergic and dopaminargic transporters to release NA and DA (Rothman et al., 2002).

Phenpromethamine

This is a sympathomimetic nasal decongestant (Todd, 1967). This is vonedrine that was shown to cause pressor effects in cats largely by indirect sympathomimetic actions (Burn and Rand, 1959). This agent is no longer listed in Sweetman (2007).

Phentermine

This is an amphetamine derivative used as appetite suppressant, acting as an indirect monoaminomimetic. It may have the same serious cardiovascular side effects as fenfluramine (certainly when used in combination with fenfluramine) (Seghatol and Rigolin, 2002). There is evidence for its weak actions as an MAO inhibitor (Ulus et al., 2000; Kilpatrick et al., 2001).

Prolintane

Its actions are similar to those of dexamphetamine. It causes release especially of DA (Paya et al., 2002), and is a psychostimulant (for example, for dementia) (Sweetman, 2007). There is limited information on this compound.

Propylhexedrine

A sympathomimetic with nasal decongestant actions, clinically (in the OTC inhaler Benzedrex). Fatalities due to cardiac actions and pulmonary hypertension with abuse of propylhexedrine have been reported (Anderson et al., 1979).

Sibutramine

This is an anti-obesity agent structurally related to amphetamine (Sweetman, 2007). It acts as a re-uptake inhibitor for NA and 5-HT, and to a lesser extent DA (Luque and Rey, 1999).

Tuaminoheptane (2-aminoheptane)

This is a nasal decongestant α-adrenoceptor agonist (Sweetman, 2007). It has pressor actions in dogs (Swanson et al., 1945).

Respiratory stimulants

A number of respiratory stimulants, often termed respiratory analeptics, are included in the Prohibited List and may have CNS-stimulant actions or actions to directly stimulate the chemoreceptors. Since there is little information on these compounds, I have chosen to discuss the best known of all these agents, doxapram (not actually on the Prohibited List). Doxapram is a respiratory stimulant used in premature newborn and to treat postoperative respiratory depression (Sweetman, 2007). Doxapram, etamivan and nikethamide stimulate all areas of CNS, including chemoreceptors, but doxapram may have some selectivity for respiratory stimulation by acting at the carotid chemoreceptors. In the chemoreceptors, doxapram may act to depolarize by blocking K+ channels, resulting in Ca2+ entry and DA release (DA stimulates the chemoreceptors), mimicking the effects of hypoxia (Anderson-Beck et al., 1995). Doxapram may also act at the carotid chemoreceptors independently of dopaminomimetic actions (Bairam et al., 1993). Doxapram has been reported to prolong electrocardiogram QT interval in the heart of premature infants (Maillard et al., 2001). Respiratory stimulants on the Prohibited List acting similarly to doxapram are amiphenazole, cropropamide, crotetamide, ethamivan and nikethamide. Pentetrazol is a respiratory stimulant with a different mode of action.

Amiphenazole

Amiphenazole has been used as respiratory stimulant, with properties similar to doxapram. It has been reported to cause lichenoid reactions in the skin (Sweetman, 2007). Like doxapram, it can reverse morphine-induced respiratory depression (Gairola et al., 1980). It no longer widely available.

Cropropamide (ethylbutamide) (in prethcamide with crotetamide)

A respiratory stimulant with actions similar to those of doxepram. It has been in use since 1950s, and is also an illicit drug used for horse doping (Sams et al., 1997).

Crotetamide (propylbutamide) (in prethcamide with cropropamide, see above)

Crotetamide is a respiratory stimulant with actions similar to those of doxepram.

Etamivan (N,N-diethyl-4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-benzamide)

This is a centrally acting respiratory stimulant and vasoconstrictor (Todd, 1967), with actions similar to those of doxapram. Instenon is a multi-ingredient preparation containing ethamivan, which is used for cerebral perfusion in surgery (Chernov et al., 2006).

Nikethamide (diethylnicotinamide)

A respiratory stimulant, but largely abandoned due to toxicity (Sweetman, 2007), its actions are similar to those of doxapram.

Pentetrazol

Pentetrazol was synthesized in 1934. It is a cardiovascular (CVS) and a respiratory stimulant used to counteract respiratory depression by drugs (Sweetman, 2007). It is also present in a number of multi-ingredient preparations for cough, for example. Causes seizures in high doses and is in fact used to induce seizures in animal models (for example, Woldbye, 1998). It acts as an antagonist of the actions of γ-aminobutyric acid (De Deyn et al., 1990), and so has a different profile from doxapram.

Nootropic agents

Nootropic agents enhance cognitive function, and are used either to limit cognitive decline (for example, in Alzheimer's disease) or to improve cerebral perfusion. Meclofenoxate and 4-phenylpiracetam are prohibited stimulants that are nootropic and have major actions on the cholinergic or GABA systems.

Meclofenoxate (centrophenoxine)

It is a nootropic agent used to treat senile dementia, and is a combination of dimethylaminoethanol and parachlorophenoxyacetate (Sweetman, 2007). It acts to increase choline (Wood and Péloquin, 1982) and acetylcholine levels (Georgiev et al., 1979), and may also increase acetylcholinesterase activity (Sharma and Singh, 1995; Shen, 2004).

4-Phenylpiracetam (carphedon)

This is a derivative of piracetam not widely available outside Russia. It is a nootrophic that has been abused in sport (Sweetman, 2007). There is limited information on this compound. Piracetam is a derivate of γ-aminobutyric acid, which improves cognition, memory, consciousness and is widely applied in the clinical treatment of brain dysfunction (He et al., 2007).

MAO inhibitors

Only one agent on the list is a MAO inhibitor, and although this also acts on the monoamine systems (see above), I will deal with it separately. Selegiline, the MAO-B inhibitor, is surprisingly included, not because of any short-term stimulant properties, but for false positive tests.

Selegiline (deprenyl)

This is an MAO-B inhibitor for Parkinson's disease and dementia. Metabolized to L-metamphetamine (less active form of metamphetamine) (Kraemer and Maurer, 2002), it has little abuse potential, although amphetamine metabolites may cause insomnia and abnormal dreams (Sweetman, 2007), and may give false positives for metamphetamine/amphetamine in drug tests.

Strychnine

Strychnine is an antagonist of glycine receptors. The glycine receptor is a ligand-gated chloride channel; opening of the chloride channels allows entry of chloride to hyperpolarize the nerves; hence, these receptors are inhibitory, and blockade of these actions removes this inhibitory control. Low doses act as a stimulant (by blocking glycinergic inhibition), but it has high toxicity, causing muscle convulsions and death. Strychnine has a well-documented history of misuse in sport. In the 1904 St Louis Olympics, Thomas Hicks (United States) won the marathon and collapsed. It took hours to revive him; he had been given brandy mixed with strychnine to revive him during the race (McCrory, 2005). A little more might have killed him.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- CNS

central nervous system

- DA

dopamine

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- MDA

methylenedioxyamphetamine

- MDEA

methylenedioxyethylamphetamine

- MDMA

methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- NA

noradrenaline

- OTC

over the counter

- VMAT-2

vesicular monoamine transporter-2

- WADA

World Anti-Doping Agency

Conflict of interest

The author states no conflict of interest.

References

- Adigun SA, Fentem PH. A comparison of the effects of salbutamol, etilefrine and dextran during hypotension and low cardiac output states in rabbit. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1984;11:627–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1984.tb00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afanas'ev II, Anderzhanova EA, Kudrin VS, Rayevsky KS. Effects of amphetamine and sydnocarb on dopamine release and free radical generation in rat striatum. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:653–658. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin and hallucinogens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:16S–23S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sahli W, Ahmad H, Kheradmand F, Connolly C, Docherty JR. Effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine on noradrenaline-evoked contractions of rat right ventricle and small mesenteric artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;422:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Garza HR, Garriott JC, Dimaio V. Intravenous prophylhexedrine (benzedrex) abuse and sudden death. Am J Med. 1979;67:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Beck R, Wilson L, Brazier S, Hughes IE, Peers CP. Doxapram stimulates dopamine release from the intact rat carotid body in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1995;187:25–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11328-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews GD, Lavin A. Methylphenidate increases cortical excitability via activation of alpha-2 noradrenergic receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:594–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Dudley AG. Methylphenidate improves prefrontal cortical cognitive function through alpha2 adrenoceptor and dopamine D1 receptor actions: relevance to therapeutic effects in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Funct. 2005;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod J. O-methylation of epinephrine and other catechols in vitro and in vivo. Science. 1957;126:400–401. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3270.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairam A, Marchal F, Crance JP, Vert P, Lahiri S. Effects of doxapram on carotid chemoreceptor activity in newborn kittens. Biol Neonate. 1993;64:26–35. doi: 10.1159/000243967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin L, Auclair A, Kleven MS, Prinssen EP, Koek W, Newman-Tancredi A, et al. Pharmacological profiles in rats of novel antipsychotics with combined dopamine D2/serotonin 5-HT1A activity: comparison with typical and atypical conventional antipsychotics. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:103–118. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280ae6c96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Brooks BP, Kulsakdinun C, De Souza EB. Pharmacologic profile of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) at various brain recognition sites. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;149:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Clark RD, Budzynski AG, Partilla JS, Blough BE, Rothman RB. N-substituted piperazines abused by humans mimic the molecular mechanism of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or ‘Ecstasy') Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;30:550–560. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumevieille M, Haramburu F, Begaud B. Abuse of prescription medicines in southwestern France. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:847–850. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthiau F, Garnier D, Argibay JA, Seguin F, Pourrias B, Grivet JP, et al. Decrease in internal H+ and positive inotropic effect of heptaminol hydrochloride: a 31P n.m.r. spectroscopy study in rat isolated heart. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;98:1233–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bexis S, Docherty JR. Role of alpha2A-adrenoceptors in the effects of MDMA on body temperature in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bexis S, Docherty JR. Effects of MDMA, MDA and MDEA on blood pressure, heart rate, locomotor activity and body temperature in the rat involve alpha-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:926–934. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerdike MJ, Vickers SP, Dourish CT. 5-HT2C receptor modulation and the treatment of obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 1999;1:207–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschko H, Richter D, Schlossman H. The oxidation of adrenaline and other amines. Biochem J. 1937;31:2187–2196. doi: 10.1042/bj0312187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boismare F, Boquet J. Letter: levodopa and dopadecarboxylase in treatment of postural hypotension. Br Med J. 1975;1:573. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5957.573-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsini F, Bendotti C, Carli M, Poggesi E, Samanin R. The roles of brain noradrenaline and dopamine in the anorectic activity of diethylpropion in rats: a comparison with D-amphetamine. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1979;26:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Koob GF. What keeps us awake: the neuropharmacology of stimulants and wakefulness-promoting medications. Sleep. 2004;27:1181–1194. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan K, Johnstone A, Fitzmaurice P, Lea R, Schenk S. Chronic benzylpiperazine (BZP) exposure produces behavioral sensitization and cross-sensitization to methamphetamine (MA) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody S, Krause C, Veit R, Rau H. Cardiovascular autonomic dysregulation in users of MDMA (‘Ecstasy') Psychopharmacology. 1998;136:390–393. doi: 10.1007/s002130050582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methamphetamine rapidly decreases vesicular dopamine uptake. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2221–2223. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugaeva LI, Verovskiǐ VE, Iezhitsa IN, Spasov AA. An acute toxicity study of bromantane. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2000;63:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn JH, Rand MJ. Fall of blood pressure after noradrenaline infusion and its treatment by pressor agents. Br Med J. 1959;1:395–397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5119.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Skolnick P. Triple uptake inhibitors: therapeutic potential in depression and beyond. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:1365–1377. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.9.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernov VI, Efimova NY, Efimova IY, Akhmedov SD, Lishmanov YB. Short-term and long-term cognitive function and cerebral perfusion in off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary L, Buber R, Docherty JR. Effects of amphetamine derivatives and cathinone on noradrenaline-evoked contractions of rat right ventricle. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;451:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary L, Docherty JR. Actions of amphetamine derivatives and cathinone at the noradrenaline transporter. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;476:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody JT. Precursor medications as a source of methamphetamine and/or amphetamine positive drug testing results. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:435–450. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman AJ, Leary WP, Asmal AC. The cardiovascular effects of etilefrine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;8:41–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00616413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly HM, Crary JL, McGoon MD, Hensrud DD, Edwards BS, Edwards WD, et al. Valvular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581–588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708283370901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock D. Anorectic drugs: use in general practice. Drugs. 1976;11:378–393. doi: 10.2165/00003495-197611050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi D, Mennini T, Gobbi M. Carrier-dependent and Ca(2+)-dependent 5-HT and dopamine release induced by (+)-amphetamine, 3,4-methylendioxymethamphetamine, p-chloroamphetamine and (+)-fenfluramine. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1735–1743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E, Loiacono R, Summers RJ. The rush to adrenaline; drugs in sport acting on the β-adrenergic system. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:598–611. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deyn PP, Marescau B, MacDonald RL. Epilepsy and the GABA—hypothesis a brief review and some examples. Acta Neurol Belg. 1990;90:65–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delicado EG, Fideu MD, Miras-Portugal MT, Pourrias B, Aunis D. Effect of tuamine, heptaminol and two analogues on uptake and release of catecholamines in cultured chromaffin cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:821–825. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90322-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JB. Weight loss medications—where do they fit in. Aust Fam Phys. 2006;35:576–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty JR. Subtypes of functional alpha1- and alpha2-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;361:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty JR. Use of knockout technology to resolve pharmacological problems. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:1–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty JR, McGrath JC. An examination of factors influencing adrenergic transmission in the pithed rat, with special reference to noradrenaline uptake mechanisms and post-junctional alpha-adrenoceptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1980;313:101–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00498564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling GP, McDonough ET, III, Bost RO. ‘Eve' and ‘Ecstasy'. A report of five deaths associated with the use of MDEA and MDMA. JAMA. 1987;257:1615–1617. doi: 10.1001/jama.257.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]