Abstract

Background and purpose:

Lung epithelial cells express pattern recognition receptors, which react to bacteria. We have evaluated the effect of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria on interleukin-8 (CXCL8) release from epithelial cells and the integrity of the epithelial barrier.

Experimental approach:

Primary cultures of human airway epithelial cells and the epithelial cell line A549 were used, and CXCL8 release was measured after exposure to Gram-negative or Gram-positive bacteria. Epithelial barrier function was assessed in monolayer cultures of A549 cells.

Results:

Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pneumoniae, induced release of CXCL8 from human airway epithelial cells. These bacteria also disrupted barrier function in A549 cells, an effect mimicked by CXCL8 and blocked by specific binding antibodies to CXCL8. Gram–negative bacteria Escherichia coli or Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced greater release of CXCL8 than Gram-positive bacteria. However, Gram-negative bacteria did not affect epithelial barrier function directly, but prevented disruption induced by Gram-positive bacteria. These effects of Gram-negative bacteria on barrier function were mimicked by FK565, an agonist of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1) receptor, but not by the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 agonist bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Neither the Gram-negative bacteria nor FK565 blocked CXCL8 release.

Conclusions:

These data show differential functional responses induced by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria in human lung epithelial cells. The NOD1 receptors may have a role in preventing disruption of the epithelial barrier in lung, during inflammatory states.

Keywords: Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NODs) proteins, interleukin-8 (CXCL8)

Introduction

Epithelial cells line the airways forming a physical and metabolic barrier between the environment and the host. Innate immune responses of the host are initiated by activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which include Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs). Human airway epithelium has been shown to express functional TLR1–6 and TLR9 (Armstrong et al., 2004; Platz et al., 2004; Greene et al., 2005). Gram-positive bacteria contain within their structure pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) specific for TLR2, which heterodimerizes with TLR1 or TLR6 (Mitchell et al., 2007). Gram-positive bacteria also contain peptidoglycans (PGN), comprising the L-lysine (Lys)-type PGN, which is a ligand for NOD2 receptors. Gram-negative bacteria contain PAMPs for a number of TLRs, the most notable being lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a ligand for TLR4. Gram-negative bacteria also contain PGN comprising the meso-diaminopimelic acid (mDAP)-type PGN, which is a ligand for NOD1 receptors (Chaput and Boneca, 2007). Lung epithelium has been shown to sense whole bacteria in vitro resulting in the release of inflammatory biomarkers. Interestingly, we (Duffin et al., 2005) and others (Mayer et al., 2007) have found that Gram-positive bacteria activate lung epithelium to release human interleukin-8 (CXCL8), substantially less than Gram-negative bacteria. CXCL8 is a chemokine that promotes the recruitment of neutrophils, which are considered the first line of defence against infection.

In this study, we have extended our previous work and that of other groups in this area investigating the ability of whole Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria to activate primary human lung epithelial cells, or the well-described human lung epithelial cell line A549 cells. To understand the role of individual PRRs, we have also used ligands specific for TLRs and NLRs. We have measured CXCL8 release and expression, as well as barrier function in the presence and absence of bacteria and selected PAMPs. Our data implied a role for CXCL8 in the loss of barrier function induced by bacteria and a role for NOD1 receptors in preserving the integrity of this barrier.

Materials and methods

Culture and preparation of bacteria

Clinical blood culture isolates of Staphylococcus aureus strain H380 and Escherichia coli 0111.B4 were stored frozen in 15% glycerol. To culture, they were first streaked onto agar plates from which single colonies were inoculated into RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and glutamine. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C overnight and then centrifuged at 800 g to pellet the bacteria. Bacteria were washed twice, and re-suspended, in sterile saline. Aliquots of the bacterial suspension were serially diluted and plated onto agar to quantify the cell density. The bacterial suspensions were then heat treated for 45 min at 80 °C to kill all bacteria (Jimenez et al, 2005). Sterility was confirmed by plating the resultant suspension. Suspensions were adjusted to 1010–1012 colony forming units per mL (CFU mL−1) and stored frozen at −20 °C in saline containing 15% glycerol.

Culture of human primary airway epithelial cells

Primary bronchial epithelial cells were obtained by protease digestion of bronchial tissue during resection of tumours from patients with lung cancer with their permission. The collection of human samples was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Royal Brompton Hospital and of St Mary's Hospital. All tissue samples used to isolate airway epithelial cells were morphologically normal, that is, non-tumour tissue. The primary epithelial cells isolated in this way were grown in T25 or T75 flasks in Airway Epithelial Cell Growth Medium (Promocell, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (0.4%), epidermal growth factor (0.5 ng mL−1), insulin (5 μg mL−1), adrenaline (0.5 μg mL−1), triiodothyronine (6.7 ng mL−1), transferrin (10 μg mL−1), retinoic acid (0.1 ng mL−1), penicillin (100 U mL−1), streptomycin (100 μg mL−1) and amphotericin (1.5 μg mL−1). This medium is hereafter referred to as ‘complete medium'. For experimental procedures, airway epithelial cells were seeded at 3.5 × 103 cells per well of 48-well plates and maintained in complete medium. Primary cultures sometimes include infected cells. To identify and exclude any cells with underlying infections, antibiotics were removed from the culture medium up to 48 h before the cultures were used experimentally. Within this time, any pre-existing infections were obvious and any such cultures with infections were not used in this study. At approximately 80% confluence, airway epithelial cells were treated with medium, 107 or 108 CFU mL−1 heat-killed E. coli or S. aureus, and supernatants collected after 24, 48 and 72 h for the measurement of CXCL8 release. Cells were used at passage 4 or less.

Culture of human lung epithelial cells (A549)

The human lung alveolar epithelial cell line A549 was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U mL−1), streptomycin (100 μg mL−1) and Modified Eagle's Medium (MEM) non-essential amino acids (1% v/v) in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Before experimentation, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a concentration of 105 cells per well and allowed to rest for 24 h before stimulation with whole bacteria or selective TLR (Alexander et al., 2007) and/or NOD ligands for 24 h. Supernatants were removed and used for the measurement of CXCL8 levels. The effect of treatments on A549 metabolism was assessed by measuring the mitochondrial-dependent reduction of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; 20 μg mL−1; Sigma, Poole, UK) to formazan. Medium was removed and formazan dissolved by the addition of dimethyl sulphoxide (100 μL per well). Formazan levels were quantified by measuring absorbance at 550 nm. This was performed after all the treatments, and unless stated, no effects were noted.

Measurement of CXCL8 production

CXCL8 (Alexander et al., 2007) content in cell-free supernatant was determined by ELISA using commercially available matched antibody pairs following a protocol supplied by the manufacturers (R&D Systems, Oxford, UK). CXCL8 concentrations were calculated using a standard curve with authentic CXCL8, provided by the above-described company and results expressed as pg mL−1 as described previously (Stanford et al., 2000).

Assessment of the effects of Gram-positive S. aureus on CXCL8 stability

Recombinant human CXCL8 (R&D Systems Ltd, Abingdon, UK) was diluted serially in 5% DMEM to concentrations of 2000, 1000, 500 and 250pg mL−1. A 90 μL volume of each standard was added to wells containing A549 cells and also onto a naked plastic culture plate containing no cells. S. aureus was diluted in 5% DMEM from their stock concentrations to produce bacterial densities of 108 CFU mL−1 mixed with standard CXCL8. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, supernatants were transferred into fresh 96-well plates and stored at −20 °C until recover could be measured after analysis of medium for CXCL8 by ELISA.

Assessment of epithelial barrier integrity

A549 cells were grown to confluence on cell culture inserts (PET membrane, 3.0 μm pore size; BD Falcon, BD-Biosciences Discover Labware, Bedford, MA, USA) in studies to assess barrier integrity. Cells were plated 48 h before the treatment. Bacteria or PAMPs were added to cells for 30 min, after which horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 1 mU mL−1; Sigma) was added to the upper compartment. Aliquots of 50 μL were collected from the lower compartment 1 h after HRP addition. HRP concentration was measured by its ability to convert pyrogallol (5% w/v, freshly prepared; Sigma), dissolved in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0; Sigma), into purpurogallin in the presence of H2O2 (0.5% w/w; Sigma) (Chance and Maehly, 1955). The total volume of the solution was 1 mL and the incubation time was 5 min; the conversion was measured by absorbance at 405 nm read in a standard spectrophotometer. The amount of purpurogallin was stoichiometrically correlated to the amount of HRP detected in the supernatant. A standard curve of HRP (0.8–62.5 mU mL−1) was used to calculate concentrations. The results were expressed as HRP U mL−1.

Measurement of CXCL8 gene expression by real-time PCR

After treatments, medium was removed from cultures, cells frozen until mRNA was extracted and cDNA generated as previously described (Paul-Clark et al., 2006). Transcript levels were determined by real-time PCR (Rotor Gene 6; Corbett Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia) using Taqman Universal PCR master mix and commercially available primers for CXCL8 (Hs00174103_m1; Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR conditions were as follows: step 1, 10 min at 95 °C; step 2, 15 s at 95 °C; step 3, 60 s at 60 °C and repeated for 40 cycles. Data from the reaction were collected and analysed (Corbett Research). Relative quantifications of gene expression were calculated using standard curves and normalized to GAPDH (NM_002046.3; Applied Biosystem).

Statistical analysis

All data shown are means±s.e.mean. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA, followed by post-tests or one-sample T-test as appropriate and as described in each figure legend using GraphPad software. Experimental n-values generally refer to data obtained in separately treated wells of cells. In most cases, experiments were performed on at least three separate experimental days. For experiments using primary cultures of human bronchial airway epithelium, cells from at least two separate donors were used. Experiments shown in Figure 3 were performed in duplicate. Values of P⩽0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reagents

Bacterial suspensions (107 or 108 CFU mL−1) were prepared as described previously. LPS (E. coli-derived, 1 μg mL−1) was purchased from Sigma. MDP-Lys18 (1 μM), FK565 (1 μM), Pam2CGDPKHPKSF (FSL-1, 100 ng mL−1) and Pam3CSK4 (300 ng mL−1) were purchased from Invivogen (San Diego, CA, USA). The working concentration for each compound was chosen from a concentration–response curve to evaluate the suboptimal effect on CXCL8 release from human bronchial epithelial cells and A549 cells (data not shown).

Results

The effect of E. coli or S. aureus on CXCL8 release by human primary or A549 lung epithelial cells

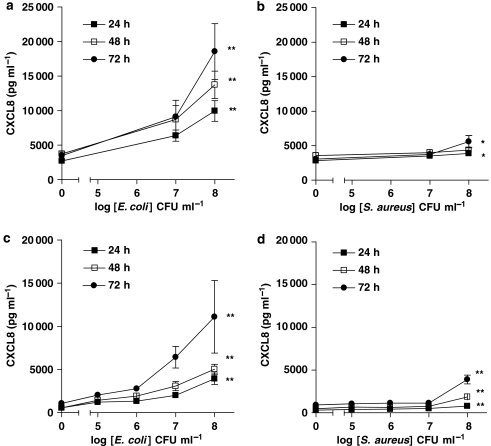

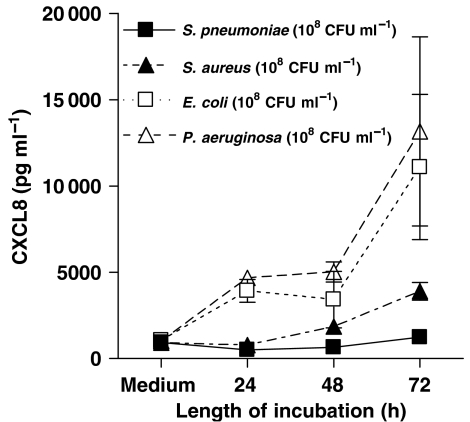

Primary cultures of human bronchial epithelial cells released low, but detectable levels of CXCL8 under control culture conditions. However after stimulation with the Gram-negative bacteria, E. coli (107 and 108 CFU mL−1), primary cultures released increased levels of CXCL8 in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Figure 1a). By contrast, when cells were stimulated with S. aureus (107 and 108 CFU mL−1) (Figure 1b), the release of CXCL8, although statistically significant at 24 and 72 h after stimulation, was much lower than that detected when cells were stimulated with E. coli at each concentration (Figure 1b). As observed with primary cultures of human bronchial epithelial cells, the human lung epithelial cell line A549 released low or undetectable levels of CXCL8 under control culture conditions. Again, as with primary cells, A549 lung epithelial cells released increased levels of CXCL8 in response to Gram-negative E. coli (105–108 CFU mL−1) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Figure 2) in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Figure 1c). However, and as was the case with primary cells, A549 lung epithelial cells released much lower levels of CXCL8 when stimulated with Gram-positive S. aureus (Figure 1d) or S. pneumoniae (Figure 2). Nevertheless, despite levels being relatively low, and again as seen with primary cells, the release induced by S. aureus from A549 cells was statistically significant at each time point (Figure 1d). Specific PAMPs for TLR4 (LPS), TLR2/1 (Pam3CSK4) or TLR2/6 (FSL-1) activated A549 epithelial cells to release increased levels of CXCL8 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of E. coli and S. aureus on human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) release from human primary airway epithelial cells (107 and 108 CFU mL−1, a–b) and A549 cells (105–108 CFU mL−1, c–d), respectively. Cells were treated for 24, 48 and 72 h. Lower release of CXCL8 was detected after S. aureus than E. coli treatment in both type of cells. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=6 (a–b) and n=8 (c–d), respectively. Statistical differences (compared with control) are denoted by *P<0.05 and **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Figure 2.

Effect of Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, P. aeruginosa), and Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and S. pneumoniae) on human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) release by A549 cells over 72 h. The bacteria concentration was 108 CFU mL−1. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=8.

Table 1.

Release of CXCL8 from A549 cells, stimulated by a range of PAMPs

| Treatment | CXCL8 release (pg mL−1) |

|---|---|

| Medium | 930±146 |

| LPS 1 μg mL−1 | 2967±184** |

| Pam3CSK4 300 ng mL−1 | 2360±201** |

| FSL-1 100 ng mL−1 | 1898±392* |

| FK565 1 μM | 1500±196 |

| MDPLys18 1 μM | 1774±265 |

| FK5651 μM+LPS 1 μg mL−1 | 4250±457** |

Abbreviations: CXCL8, human interleukin-8; FSL-1, lipopeptide Pam2Cys-GDPKHPKSF; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; Pam3CSK4, triacylated synthetic lipoprotein.

Effect of different PAMPs on CXCL8 release from A549 cells. Cells were treated for 24 h. LPS (1 μg mL−1), FSL-1 (100 ng mL−1) and Pam3CSK4 (300 ng mL−1) induced a release of CXCL8 compared with control treated cells. No increase in CXCL8 release was seen when cells were treated with FK565 or MDPLys18. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=5. Statistical differences (compared with medium control wells) are denoted by *P<0.05 and **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

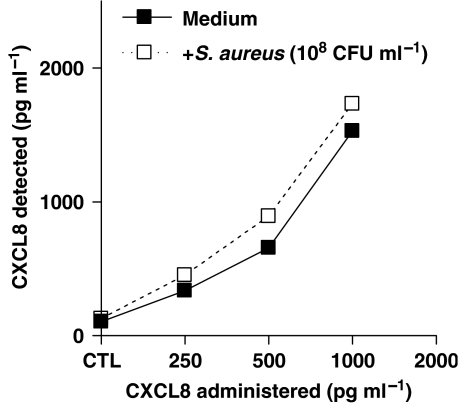

Effect of S. aureus on stability of CXCL8 in culture medium

Bacteria may contain molecules that can neutralize CXCL8 protein (Edwards et al., 2005). To be sure that the low yield of CXCL8 from airways cells co-incubated with Gram-positive bacteria was not due to degradation, we performed experiments where known concentrations of recombinant CXCL8 (0.25–1 ng mL−1) were incubated with S. aureus (108 CFU mL−1) for 24 h under identical culture conditions as those described above. S. aureus had no effect on CXCL8 stability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of S. aureus (108 CFU mL−1) on human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) stability in culture medium over 24 h. S. aureus did not induce CXCL8 degradation. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=2.

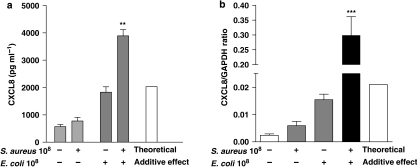

Effect of Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive S. aureus alone and in combination on CXCL8 release and gene induction

As seen above, Gram-positive S. aureus induced low but significant levels of CXCL8 from A549 epithelial cells after 24 h, whereas E. coli stimulation induced the release of large amounts of chemokine (Figure 4a). When S. aureus and E. coli were added together, there was a marked increase in CXCL8 release (Figure 4a). In line with observations made with mature protein release, CXCL8 gene expression was induced by both bacteria, with levels being higher in cells treated with E. coli than in S. aureus (Figure 4b). When cells were treated with a combination of E. coli and S. aureus, the CXCL8 gene expression was synergistically increased, compared with when cells were treated with each bacterium separately (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Effect of E. coli (108 CFU mL−1) and S. aureus (108 CFU mL−1) on human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) production (a) and gene expression (b) over 24 and 3 h, respectively. The theoretical additive levels calculated for CXCL8 release is denoted by the white bar and was calculated by adding the mean amount of CXCL8 detected after treatment of the A549 cells with E. coli and S. aureus alone, either for the protein release (a) or for the mRNA levels (b). Statistical differences are denoted by **P<0.0005 (a) and ***P<0.0001 (b); one sample T-test, comparing the actual CXCL8 release to the theoretical additive effect. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=6 (a) and 3 (b), respectively.

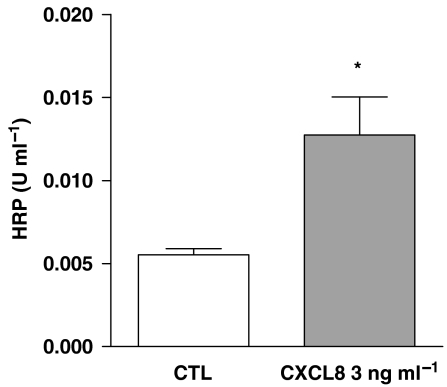

Effect of CXCL8 on barrier function in monolayers of A549 epithelial cells

Under control culture conditions, a confluent monolayer of epithelial cells form a competent barrier, that is, impermeable to large proteins. CXCL8 (3 ng mL−1) added to cells for 1 h caused a disruption of the barrier function resulting in a significant increase in the passage of HRP through the monolayer (Figure 5). The effects of CXCL8 on barrier function in this study were specific, as they were blocked by a specific binding antibody to CXCL8 (Figure 6c).

Figure 5.

Effect of human recombinant human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) (3 ng mL−1) on barrier integrity. The detection of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in the lower insert compartment was increased after CXCL8 treatment compared with medium alone. Data represents mean±s.e.mean, n=16. Statistical difference is denoted by *P<0.01; Student's t-test.

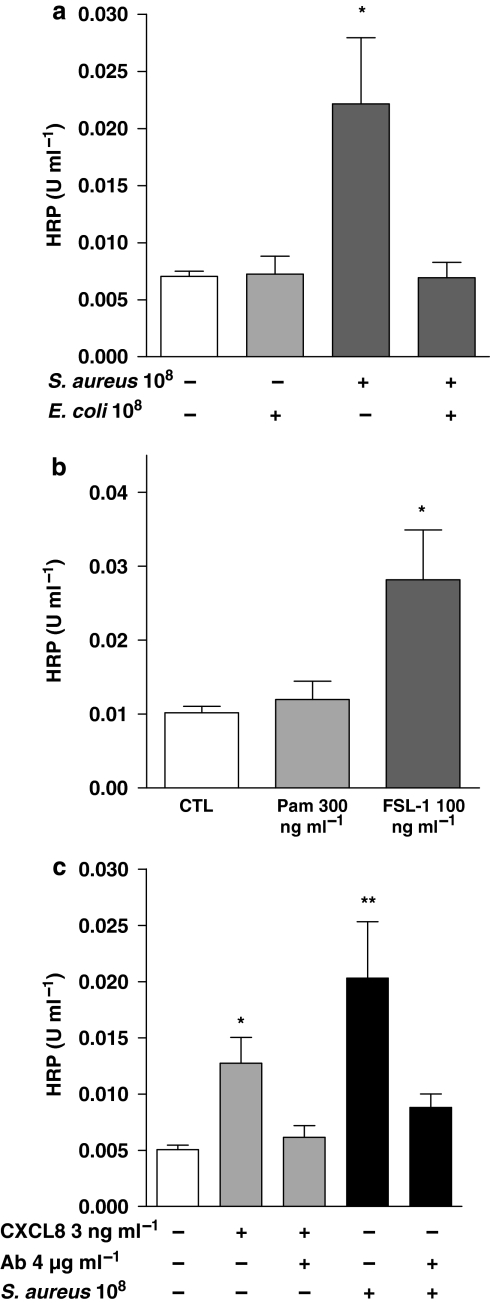

Figure 6.

Effect of E. coli (108 CFU mL−1) and S. aureus (108 CFU mL−1) (a) or Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 ligands, lipopeptide Pam2Cys-GDPKHPKSF (FSL-1; 100 ng mL−1) and triacylated synthetic lipoprotein (Pam3CSK4; 300 ng mL−1) (b) on barrier integrity. (c) The effect of the neutralizing antibody for human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) on barrier function after CXCL8 (3 ng mL−1) and S. aureus treatment. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=16 (a), n=12 (b), n=8 (c), respectively. Statistical difference is denoted by *P<0.05 and **P<0.01; Student's t-test and one way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Effect of Gram-negative E. coli, Gram-positive S. aureus or specific PAMPs on barrier function in A549 epithelial cells: role of CXCL8

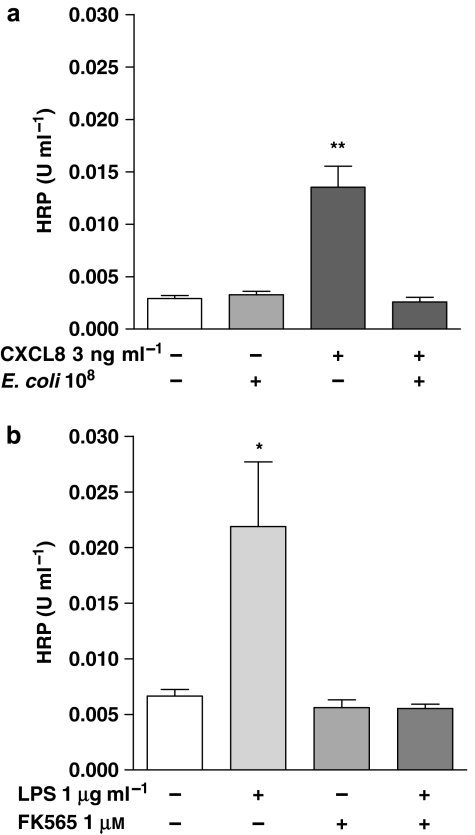

Gram-negative E. coli (108 CFU mL−1) had no significant effect on barrier function in epithelial cells (Figure 6a). By contrast, S. aureus (108 CFU mL−1) caused a significant disruption of barrier function (Figure 6a). The effects of S. aureus were mimicked by FSL-1, which activates the TLR2/6 heterodimer. Pam3CSK4 had a weak tendency on barrier function, which did not reach statistical significance (Figure 6b). Interestingly, the effects of S. aureus on barrier function were prevented by co-treatment with E. coli (Figure 6a). The activity of S. aureus on barrier function was mediated by CXCL8, as neutralizing antibodies to CXCL8 prevented its effects (Figure 6c). In line with observations made with S. aureus, the effects of authentic CXCL8 on barrier function were blocked by co-treatment with E. coli (Figure 7a). LPS induced significant CXCL8 release from A549 cells, but FK565, which activates NOD1 receptors, did not. (Table 1). In the present set of experiments, barrier function of A549 cells was disrupted by LPS but not by FK565 (Figure 7b). Furthermore, FK565 prevented the disruptive effects of LPS on barrier function, when they were given together (Figure 7b). Co-treatment of A549 cells with this combination of LPS and FK565 resulted in an additive increase in CXCL8 release (Table 1).

Figure 7.

(a) Effect of E. coli (108 CFU mL−1) on barrier disruption induced by human interleukin-8 (CXCL8). (b) Effect of FK565 (1 μM) on the barrier disruption induced by LPS (1 μg mL−1). FK565 mimicked the effect of E. coli in preventing barrier disruption induced by human interleukin-8 (CXCL8) and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS_ respectively. Data represent mean±s.e.mean, n=4 (a), n=8 (b), respectively. Statistical difference is denoted by *P<0.05 and **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that primary cultures of human airway epithelium detect and react selectively to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and to a range of selected PAMPs. Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria induced CXCL8 release by human bronchial epithelial cells, although the effect of Gram-negative bacteria was more pronounced. Gram-positive bacteria, but not Gram-negative bacteria, disrupted barrier function, which was mediated by CXCL8. Interestingly, Gram-negative bacteria prevented the effects of Gram-positive bacteria on barrier function, and this prevention was mediated independent of the effects on CXCL8 release. The effects of Gram-negative bacteria on barrier function were mimicked by specific PAMPs for NOD1, but not TLR4.

Airway epithelium is continuously exposed to a wide variety of pathogens and these cells are known to express a range of TLRs (Armstrong et al., 2004; Greene et al., 2005), but their role in immune function is unclear. In this study we show that, for two separate types of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, airway epithelium reacts by releasing CXCL8. In our study, we have used heat-killed bacteria that retain many of the inflammatory qualities of live bacteria. However, as with all studies using killed pathogens, results can be different when live infections are studied. We found that Gram-negative bacteria induced greater levels of CXCL8 release from lung epithelial cells than Gram-positive bacteria (Duffin et al., 2005). Similar observations have recently been made by others (Mayer et al., 2007) who suggest that a lack of expression of CD36 accounts, at least in part, for the reduced response of these cells to Gram-positive bacteria. CD36 is a scavenger receptor for lipids, which facilitates the sensing of selected PAMPs by the TLR2/6 heterodimer (Hoebe et al., 2005). Gram-positive bacteria contain PAMPs for TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 heterodimer complexes, whereas Gram-negative bacteria contain PAMPs for TLR4 (Mitchell et al., 2007). In our study and that of Mayer et al. (2007), lung epithelium released significant amounts of CXCL8 in response to PAMPs for the TLR2/1 (Pam3CSK4), TLR2/6 (FSL-1) or TLR4 (LPS). Bacteria also contain PGN that can be broken down to PAMPs for NLRs. Products of PGN from Gram-negative bacteria activate NOD1 (and NOD2), whereas those from PGN from Gram-positive bacteria activate NOD2. In our study, we found that a selective PAMPs for NOD1 (FK565; (Ahmed et al., 1989; Cartwright et al., 2007) had minimal effect on the ability of lung epithelium to release CXCL8. Similarly, we found that muramyl dipeptide (MDP) which activates NOD2 (Fritz et al., 2006) slightly stimulated lung epithelium to release CXCL8.

In other cell types, activation of TLR2 and TLR4 pathways can result in synergistic release of inflammatory mediators (Paul-Clark et al., 2006; Schroder et al., 2006). In this study, we show that Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria enhance upregulation of CXCL8 release and gene expression in lung epithelium, which is consistent with observations, made for other genes and cell types.

Others have shown in endothelial cells that CXCL8 disrupts barrier function (Talavera et al, 2004), suggesting that its effects are mediated by the modulation of the tight junctions either by affecting zona occludens-1 protein and/or adhesion molecule expression. Our present data suggest the same phenomenon may exist in human lung epithelial cells. Moreover, we show that Gram-positive S. aureus similarly disrupts barrier function. The effects of S. aureus in our model were blocked by binding antibodies to CXCL8 and were mimicked by FSL-1, and to a much lesser degree by Pam3CSK4. By contrast, E. coli did not affect barrier function in these cells. As mentioned above, E. coli induced substantially more CXCL8 release than S. aureus.

Why then does E. coli not induce a disruption in barrier function in lung epithelial cells? One possible explanation for our observations was that E. coli was having dual effects on barrier function and the disruption that would be induced by CXCL8 was being prevented. This possibility was confirmed in experiments where the co-treatment with E. coli completely prevented barrier function disruption induced by either CXCL8 or S. aureus. As mentioned above, E. coli contains PAMPs for TLR4 and for NOD1. We found that the activation of TLR4 with LPS mimicked the effects of E. coli on CXCL8 release, but unlike the whole bacteria, LPS induced a clear disruption of barrier function in these cells. By contrast, activation of NOD1 with FK565 had no direct effect on barrier function, and like whole E. coli, prevented disruption of the barrier. It is beyond the scope of this current study to establish the physiological relevance of our findings. Clearly, bacterial infection results in inflammation in the lung leading to a disruption in barrier function. This is the case for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Our observations using isolated human epithelial cells in vitro are therefore simply modelling the response of these stromal cells without the participation of associated adjoining cells and/or recruited leukocytes. The relevance of our data in this context perhaps is an understanding of how individual PAMPs may interact to cause effects in these cells. Our findings that FK565 did not disrupt barrier function by itself and prevented disruption induced by other agonists, is interesting, although its meaning for events in vivo is unclear. However, although both LPS and FK565 induced shock and signs of sepsis, only LPS, and not FK565, induced detectable signs of lung inflammation (Cartwright et al, 2007). It is tempting to speculate that these in vivo findings may be explained by the observations made here using human cells in vitro.

It is also beyond the scope of this study to elucidate the pathways by which bacteria, TLRs and NLRs interact via CXCL8-dependent and CXCL8-independent pathways to modulate barrier function of lung epithelium. However, our data suggest that such interactions are functionally relevant and identify NOD1 as a potential therapeutic target in the prevention of lung inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Andrew Nicholson from Royal Brompton Hospital and Dr Rex D Stanbridge from St Mary's Hospital, London, United Kingdom. This work was supported by the British Lung Foundation. Dr Stanbridge RD, for the collection of human samples at St Mary's Hospital.

Abbreviations

- CXCL8

human interleukin-8

- FSL-1

lipopeptide Pam2Cys-GDPKHPKSF

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NOD1

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1

- Pam3CSK4

triacylated synthetic lipoprotein

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PPRs

pathogen response receptors

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

References

- Ahmed K, van der Meide PH, Turk JL. Effect of anticancer drugs on the release of interferon gamma in vitro. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1989;30:213–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01665007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150 Suppl 1:S1–S168. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong L, Medford AR, Uppington KM, Robertson J, Witherden IR, Tetley TD, et al. Expression of functional Toll-like receptor-2 and -4 on alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;3:241–245. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0078OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright N, Murch O, McMaster SK, Paul-Clark MJ, van Heel DA, Ryffel B, et al. Selective NOD1 agonists cause shock and organ injury/dysfunction in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:595–603. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Maehly AC. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods in Enzymol. 1955;2:764–775. doi: 10.1002/9780470110171.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaput C, Boneca IG. Peptidoglycan detection by mammals and flies. Microb Infect. 2007;9:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobos KM, Spotts EA, Quinn FD, King CH. Necrosis of lung epithelial cells during infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is preceded by cell permeation. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6300–6310. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6300-6310.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin C, Paul-Clark M, McMaster S, Sriskandan S, Mitchell JA.Differential effects of Gram negative versus Gram positive bacteria on IL-8 release by human lung epithelial cells: role of Toll like receptors 2 and 4 Br J Pharmacol 20053(2): abstract number 160P

- Edwards RJ, Taylor GW, Ferguson M, Murray S, Rendell N, Wrigley A, et al. Specific C-terminal cleavage and inactivation of interleukin-8 by invasive disease isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:783–790. doi: 10.1086/432485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz JH, Ferrero RL, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. Nod-like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat Immuno. 2006;7:1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/ni1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene CM, Carroll TP, Smith SG, Taggart CC, Devaney J, Griffin S, et al. TLR-induced inflammation in cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1638–1646. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebe K, Georgel P, Rutschmann S, Du X, Mudd S, Crozat K, et al. CD36 is a sensor of diacylglycerides. Nature. 2005;433:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature03253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez R, Belcher E, Sriskandan S, Lucas R, McMaster SK, Vojonovic I, et al. Role of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in the induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in vascular smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407655101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AK, Muehmer M, Mages J, Gueinzius K, Hess C, Heeg K, et al. Differential recognition of TLR-dependent microbial ligands in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:3134–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JA, Paul-Clark MJ, Clarke GW, McMaster SK, Cartwright N. Critical role of Toll-like receptors and nucleotide oligomerisation domain in the regulation of health and disease. J Endocrinol. 2007;193:323–330. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Clark MJ, McMaster SK, Belcher E, Sorrentino R, Anandarajah J, Fleet M, et al. Differential effects of Gram-positive versus Gram-negative bacteria on NOSII and TNFalpha in macrophages: role of TLRs in synergy between the two. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:1067–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz J, Beisswenger C, Dalpke A, Koczulla R, Pinkenburg O, Vogelmeier C, et al. Microbial DNA induces a host defense reaction of human respiratory epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1219–1223. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Signal integration between IFNgamma and TLR signalling pathways in macrophages. Immunobiology. 2006;211:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford SJ, Pepper JR, Mitchell JA. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, but not interleukin-8, production by human vascular cells: role of cAMP. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:677–682. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera D, Castrilllo AM, Dominguez MC, Gutierrez AE, Meza I. IL8 release, tight junction and cytoskeleton dynamic reorganization conducive to permeability increase are induced by dengue virus infection of microvascular endothelial monolayers. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1801–1813. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]