Abstract

Background and purpose:

As baclofen is active in patients with anxiety disorders, GABAB receptors have been implicated in the modulation of anxiety. To avoid the side effects of baclofen, allosteric enhancers of GABAB receptors have been studied to provide an alternative therapeutic avenue for modulation of GABAB receptors. The aim of this study was to characterize derivatives of (R,S)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one (rac-BHFF) as enhancers of GABAB receptors.

Experimental approach:

Enhancing properties of rac-BHFF were assessed in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) cells by Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader and GTPγ[35S]-binding assays, and in rat hippocampal slices by population spike (PS) recordings. In vivo activities of rac-BHFF were assessed using the loss of righting reflex (LRR) and stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH) models.

Key results:

In GTPγ[35S]-binding assays, 0.3 μM rac-BHFF or its pure enantiomer (+)-BHFF shifted the GABA concentration–response curve to the left, an effect that resulted in a large increase in both GABA potency (by 15.3- and 87.3-fold) and efficacy (149% and 181%), respectively. In hippocampal slices, rac-BHFF enhanced baclofen-induced inhibition of PS of CA1 pyramidal cells. In an in vivo mechanism-based model in mice, rac-BHFF increased dose-dependently the LRR induced by baclofen with a minimum effective dose of 3 mg kg−1 p.o. rac-BHFF (100 mg kg−1 p.o.) tested alone had no effect on LRR nor on spontaneous locomotor activity, but exhibited anxiolytic-like activity in the SIH model in mice.

Conclusions and implications:

rac-BHFF derivatives may serve as valuable pharmacological tools to elucidate the pathophysiological roles played by GABAB receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Keywords: GABAB receptor, positive allosteric modulator, rac-BHFF, class C GPCR, anxiety, population spike, loss of righting reflex, stress-induced hyperthermia

Introduction

The majority of inhibitory synapses in the CNS employ GABA as their neurotransmitter. After its release, GABA binds to, and activates two distinct classes of receptors, ionotropic GABAA/C and metabotropic GABAB (Hill and Bowery, 1981). GABAB receptors are present in most regions of the mammalian brain on presynaptic terminals and postsynaptic neurons. They are involved in the fine-tuning of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Presynaptic GABAB receptors (as auto- and hetero-receptors) through modulation of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels (P/Q and N type) inhibit the release of GABA and many other neurotransmitters. Postsynaptic GABAB receptors activate G-protein-coupled, inwardly rectifying, K+ (GIRK) channels and negatively regulate adenylyl cyclase (Bettler et al., 2004). Native GABAB receptors are heteromeric structures composed of two types of subunits, GABAB(1) and GABAB(2) subunits (Kaupmann et al., 1997, 1998). The structures of GABAB(1) and GABAB(2) indicate that they belong to the class C family of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Other members of the class C GPCRs include the metabotropic glutamate (mGlu1–8), Ca2+-sensing (CaSR), vomeronasal, pheromone and putative taste receptors (Pin et al., 2003). The class C GPCRs are characterized by two distinct topological domains: a long extracellular amino-terminal domain, which contains a Venus flytrap module for the agonist binding and the seven-transmembrane domain (7TMD) segments plus intracellular carboxyl-terminal domain that is involved in receptor activation and G-protein coupling. The mechanism of agonist-induced receptor activation of GABAB(1,2) heterodimers is unique among the GPCRs. In the heteromer, GABA binds only to the Venus flytrap module of GABAB(1) (Galvez et al., 2000), whereas the GABAB(2) is needed for the coupling and activation of G proteins (Havlickova et al., 2002; Kniazeff et al., 2002). The 7TMD region of class C GPCRs forms the binding pocket for the novel class of compounds acting as positive or negative allosteric modulators (Pin et al., 2005). During recent years, several highly selective positive allosteric modulators have been reported for class C GPCRs, including CaSR (NPS R-467 ((R)-N-(3-methoxy-α-phenylethyl)-3-phenyl-1-propylamine hydrochloride) and NPS R-568 ((R)-N-(3-methoxy-α-phenylethyl)-3-(2′-chlorophenyl)-1-propylamine hydrochloride)) (Hammerland et al., 1998), mGlu1 (RO 67-7476 ((S)-2-(4-fluoro-phenyl)-1-(toluene-4-sulphonyl)-pyrrolidine)) (Knoflach et al., 2001), mGlu2 (LY487379 (N-(4-(2-methoxyphenoxy)-phenyl-N-(2,2,2-trifluoroethylsulphonyl)-pyrid-3-ylmethylamine)) (Johnson et al., 2003) and mGlu5 (DFB (3,3′-difluorobenzaldazine) and CDPPB (3-cyano-N-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-yl)benzamide)) (Kinney et al., 2005). Interestingly, these positive modulators bind to allosteric sites located within the 7TMD region, an action that enhances the agonist affinity by stabilizing the active state of the 7TMD region (Knoflach et al., 2001; Petrel et al., 2004; Muhlemann et al., 2006).

GABAB receptors are strategically located to modulate the activity of various neurotransmitter systems. Therefore, GABAB receptor ligands have potential in the treatment of psychiatric and neurological disorders, such as anxiety, depression, epilepsy, schizophrenia and cognitive disorders (Vacher and Bettler, 2003; Bettler et al., 2004). For example, recent preclinical studies have shown that both GABAB receptor agonists and antagonists could have an anxiolytic and antidepressant profile in animal tests of anxiety and depression (Pilc and Nowak, 2005; Frankowska et al., 2007; Partyka et al., 2007), possibly reflecting complex in vivo direct interactions with pre- and postsynaptic GABAB receptors. One of the main ligands that has been investigated extensively in preclinical and clinical studies is baclofen, a selective GABAB receptor agonist with EC50 of 210 nM at native receptor. However, poor blood–brain barrier penetration, very short duration of action, rapid tolerance and narrow therapeutic window (muscle relaxation, sedation) have restricted its utility (Bowery, 2006). Because of their allosteric and activity-dependent mechanism of action, positive GABAB modulators offer an opportunity for the development of therapeutic compounds with improved side-effect profile and less tolerance. The first reported positive allosteric modulators of GABAB receptor were CGP7930 (2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-phenol) and GS39783 (N,N′-dicyclopentyl-2-methylsulphanyl-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4,6-diamine) (Urwyler et al., 2001, 2003). These modulators have been shown to have no effect on their own at GABAB receptors, but in synergy with GABA, they increase both the potency and maximal efficacy of GABA at the GABAB(1,2) (Urwyler et al., 2001, 2003). Furthermore, the in vitro potentiation of the GABA effect by CGP7930 could be corroborated in an in vivo mechanism-based paradigm, in which pretreatment with CGP7930 resulted in a potentiation of the baclofen-induced loss of righting reflex (LRR) in DBA mice. This combined effect was blocked by GABAB antagonists (Carai et al., 2004). CGP7930 also potentiated baclofen-induced depression of dopamine neuron activity in the rat ventral tegmental area (Chen et al., 2005). Similarly, GS39783 enhanced GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition of cAMP formation in rat striatum in vivo (Gjoni et al., 2006).

Here, we report on the identification of derivatives of (R,S)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one (rac-BHFF) as potent allosteric enhancers of GABAB receptors. We report that rac-BHFF enhanced the GABAB receptor agonist-stimulated responses in the Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader (FLIPR) assay and GTPγ[35S] binding, was effective in enhancing the inhibitory effect of baclofen on population spike (PS) in hippocampal slices and potentiated the baclofen-induced LRR in mice. Furthermore, we show that rac-BHFF has anxiolytic-like properties in stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH) in mice.

Methods

Isolation of GABAB receptor subunit cDNAs and generation of CHO-Gα16-GABAB(1a,2a) stable cell line

The human GABAB receptor subunit cDNAs, GABAB(1a) (AC: AJ225028; Kaupmann et al., 1997) and GABAB(2a) (AC: AJ011318; Kaupmann et al., 1998), were isolated from a human brain cerebellum cDNA library (BD Marathon-ready cDNA; BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) by PCR using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). To express a 1:1 ratio of GABAB(1a) and GABAB(2a) receptor subunits, the two expression cassettes, CMV-hGABAB(1a)-polyAsite+termination and CMV-hGABAB(2a)-polyAsite+termination were constructed. These two expression cassettes were then inserted into pcDNA6/Myc-HisB vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with blasticidin as selection marker. The functionality of this expression construct was tested by electrophysiology using the GIRK model (Malherbe et al., 2001), which showed GABA-evoked GIRK channel currents in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-GIRK1/2 cell line transfected by pcDNA6-hGABAB(1a,2a).

The CHO-Gα16 cell line that stably overexpresses human Gα16 with hygromycin B as selection marker was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium:F12/ISCOVE supplemented with 5% dialysed fetal calf serum, 100 μg mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin and 100 μg mL−1 hygromycin B. The CHO-Gα16 cell line was transfected with pcDNA6-hGABAB(1a,2a) using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were transferred to a medium containing 10 μg mL−1 blasticidin. After 2 weeks, clonal lines were isolated and cultured independently. Three cell lines out of forty gave GABA-induced responses in the FLIPR assay. A single clonal line 10-14 was further generated by limited dilution of the clone-10. Furthermore, the expression level of hGABAB(1a,2a) in the clonal line 10-14 was characterized by saturation analysis using [3H]CGP54626. The membranes from the CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) stable clonal line 10-14 bound [3H]CGP54626 in a saturable manner with Kd=1.2 nM and Bmax=32.6 pmol per mg protein.

Intracellular Ca2+ mobilization assay

The CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) stable clonal line 10-14 cells were seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well in poly-D-lysine-treated, 96-well, black/clear-bottomed plates (BD Biosciences). After 24 h, the cells were loaded for 90 min at 37 °C with 4 μM fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (catalogue no. F-14202; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) in loading buffer (1 × Hanks' balanced salt solution, 20 mM HEPES and 2.5 mM probenecid). The cells were washed five times with loading buffer to remove excess dye, and intracellular calcium mobilization [Ca2+]i was measured using a FLIPR-96 (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The enhancers were applied 15 min before the application of GABA. Concentration–response curves of GABA (0.0003–30 μM) were determined in the absence and presence of various concentrations of enhancer. The maximum enhancing effect (% Emax) and potency (EC50 value) of each enhancer were determined from concentration–response curve of the enhancer (0.001–30 μM) in the presence of 10 nM GABA (EC10). Responses were measured as peak increase in fluorescence minus basal, normalized to the maximal stimulatory effect induced by 10 μM GABA alone (considered 100%) and 10 nM GABA alone (considered 0%). The data were fitted with a four-parameter logistic equation according to the Hill equation: y = 100/(1 + (x/EC50nH, where nH=slope factor using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA). The experiments were performed at least three times in triplicate and the mean±s.e.mean value was calculated.

Preparation of membranes from CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) line 10-14 and GTPγ[35S]-binding assay

CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) line 10-14 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium:F12/ISCOVE supplemented with 5% dialysed fetal calf serum, 100 μg mL−1 penicillin–streptomycin, 100 μg mL−1 hygromycin B and 10 μg mL−1 blasticidine to a confluency of 80%. The cells were harvested using Accutase/PBS (1:4) (catalogue no. A6964; Sigma, Buchs, Switzerland) and washed three times with ice-cold PBS and frozen at –80 °C. The cell pellet was suspended in ice-cold 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 and homogenized with a Polytron (Kinematica AG, Basel, Switzerland) for 10 s at 10 000 r.p.m. After centrifugation at 48 000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, the pellet was resuspended in ice-cold 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, homogenized, re-centrifuged as above. This pellet was further resuspended in a smaller volume of ice-cold 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4. After homogenization for 10 s at 10 000 r.p.m., the protein content was measured using the BCA method (Pierce, Socochim, Lausanne, Switzerland) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The membrane homogenate was frozen at –80 °C before use.

After thawing on ice, the membrane homogenates were centrifuged at 48 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and pellet was resuspended in ice-cold water (LiChrosolv water for chromatography; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). After 1 h incubation on ice, the membranes were re-centrifuged as above. The membranes were then resuspended in ice-cold assay buffer, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 2 mM CaCl2 and 100 mM NaCl (pH 7.5). Wheatgerm agglutinin-coated SPA beads (RPNQ0001; Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) were suspended in the same assay buffer (40 mg of beads mL−1). Membranes and beads were mixed (beads: 13 mg mL−1; membranes: 200 μg per mL protein) and incubated with 10 μM GDP at room temperature for 1 h, with mild agitation. GTPγ[35S] binding was performed in 96-well microplates (picoplate; Packard) in a total volume of 180 μL with 6–10 μg membrane protein and 0.3 nM GTPγ[35S]. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 10 μM unlabelled GTPγS. For the functional assay, GABA concentration-dependent (3 nM–300 μM) stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding was performed in the absence or presence of various concentrations of enhancers (0, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10 and 30 μM). To measure the enhancer's potency (EC50 value), enhancer concentration-dependent (1 nM–30 μM) stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding was carried out in the absence or presence of various GABA concentrations (0, 0.2, 0.6, 1, 6 and 20 μM). Plates were sealed and agitated at room temperature for 2 h. The beads were then allowed to settle and the plate counted in a Top-Count (Packard) using quench correction. All compounds were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulphoxide, and diluted in assay buffer. The diluted stock was then applied to the assay at a final dimethyl sulphoxide concentration of 0.3%. The stimulation curves were fitted as mentioned above to the Hill equation. The experiments were performed at least three times in triplicate and the mean±s.e.mean value was calculated.

Electrophysiological recordings

All animal and experimental procedures received prior approval from the City of Basel Cantonal Animal Protection Committee based on adherence to federal and local regulations.

Wistar rats weighing 90–100 g (35–40 days old) were anaesthetized in a 2.5% isoflurane–96.5% oxygen mixture and decapitated. The hippocampi were dissected and 400-μm slices were transversely cut with a tissue chopper (Sorvall, Newton, CT, USA). The slices were then maintained in a submerged chamber and perfused at 32 °C in a solution containing 124 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM D-glucose, 4 mM sucrose, oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (pH 7.4, 307 mosM). For electrophysiological recordings, a hippocampal slice was placed in the recording chamber, which was constantly superfused with the oxygenated salt solution and kept at 32 °C for 1 h before recording. PS was recorded from the CA1 region of the stratum pyramidale by using a glass micropipette (1–3 MΩ) containing 2 M NaCl. PS was evoked by orthodromic stimulation (0.1 ms, 250–500 μA) of Schaffer collaterals (stratum radiatum/lacunosum) with insulated bipolar platinum/iridium electrodes >500 μm away from the recording electrode. The stimulus intensity that induced a PS near to the maximum amplitude was used as the test stimulus. PS was amplified with a Cyberamp 380 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), filtered at 2.4 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz with a Digidata 1322 acquisition board (Axon Instruments) for subsequent storage on personal computer (Compaq Deskpro EN).

To obtain concentration–response relationships, PS was evoked at 30-s intervals and increasing concentrations of baclofen were applied to the slice. For each concentration of baclofen, the PS amplitude obtained from four averaged responses was measured. Baclofen was then removed from the salt solution. After a full recovery, rac-BHFF was first applied to the same slice alone and then in the presence of increasing concentrations of baclofen. PS amplitudes were fitted with the logistic equation: PS = PSmax/(1 + (x/IC50)nH

, where PSmax is the maximum PS amplitude, IC50 is the half-maximum effective concentration, x is the concentration of baclofen and nH is the Hill slope. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean.

In vivo assessment of rac-BHFF

Drug treatment of animals

All compounds were prepared immediately prior to use in vehicle (in 10 mL kg−1 of a 4:1:15 mixture containing Cremophor EL, 1,2-propanediol and distilled water; Carai et al., 2004). Baclofen was dissolved in 0.3% (w/v) Tween-80 in physiological saline (0.9% NaCl). The volume of administration was 10 mL kg−1.

LRR assay

Male DBA mice (23–26 g) supplied from Iffa Credo, Lyon, France, were used. They were group-housed in transparent polycarbonate cages (type 3; length 42 cm × width 46 cm × height 15 cm) at controlled temperature (20–22 °C) and 12:12 h light–dark cycle (lights on 0600 hours). All animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. rac-BHFF (1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1 p.o.), CGP7930 (10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1 p.o.) or vehicle was administered to male DBA mice. After 45 min, the fixed dose of 20 mg kg−1 baclofen (i.p.) was injected. The baclofen dose of 20 mg kg−1 was determined as a subthreshold dose, whereas 40 mg kg−1 significantly induced LRR (data not shown). After the injection of baclofen, mice were individually housed. Starting 15 min after the injection of baclofen, the mice were tested for LRR every 15 min for a total of nine trials. Briefly, the mice were put on their back on a tissue on a table, if they did not show a righting response such that they had all four paws under their body within 60 s, they were considered to have LRR. For each animal, the total number of LRR trials was counted.

SIH in mice

Male NMRI mice (20–25 g) supplied from RCC Ltd, Fullinsdorf, Switzerland, were used. They were individually housed (macrolon cage: 26 cm × 21 cm × 14 cm) at controlled temperature (20–22 °C) and 12:12 h light–dark cycle (lights on 0600 hours). All animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. A detailed description of the SIH test procedure can be found elsewhere (Spooren et al., 2002). Body temperature was measured in each mouse twice; at t=0 (T1) and t=+15 min (T2). T1 served as the handling stressor. The difference in temperature (T2−T1) was considered to reflect SIH. Mice received treatment with rac-BHFF (doses: 3, 10, 30 or 100 mg kg−1, p.o.), or vehicle 60 min before T1 and subsequently underwent the SIH procedure.

Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamic and drug interaction

Pharmacokinetic experiments were performed in male NMRI mice (20–25 g) from RCC Ltd, Fullinsdorf, Switzerland. Mice were dosed either p.o. or i.v. into the tail vain. At defined time points, terminal plasma and brain tissue were collected. Two animals per group were killed at 0.08, 0.3, 1, 2, 4 and 8 h (i.v. administration of 1.5 mg kg−1 rac-BHFF) or 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 h (p.o. administration of 25 mg kg−1 rac-BHFF) after dosing. The formulation used was either saline (i.v. administration) or a 4:1:15 mixture containing Cremophor EL, 1,2-propanediol and distilled water (p.o. administration). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by non-compartmental analysis of plasma concentration–time curves using WinNonlin 4.1 software (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). For pharmacodynamic and drug interaction studies, the brain and plasma exposure of rac-BHFF and baclofen were monitored during various pharmacological protocols in male DBA mice (23–26 g) supplied from Iffa Credo.

Sample preparation and analysis by LC/MS-MS

For sample preparation, 50 μL of plasma was mixed with 150 μL of methanol containing an internal standard. Brain tissue (that is, one mouse brain) was diluted with three volumes of water and homogenized in an ice-water bath using an ultrasonic probe. Homogenized brain sample (50 μL) was mixed with 150 μL methanol containing an internal standard. Brain and plasma samples were centrifuged, 100 μL of the upper organic phase was diluted with one volume of water and analysed by LC and tandem mass spectrometry. In brief, the chromatographic system consisted of two Shimadzu LC10 AD high-pressure gradient pumps (Schimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The analytical column was a MS-X-Terra C18, 3.5 μm (50 mm × 1 mm i.d.; Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The injection volume was 1 μL. The mobile phase consisted of a gradient over 3 min from formic acid/methanol/water (1:20:80) to methanol delivered with a flow rate of 0.08 mL min−1. Under these conditions, quantitative hydrolysis of rac-BHFF to BHFHP occurred. The LC system was coupled to a PE Sciex API 2000 quadrupole mass spectrometer with ionspray interface (Sciex, Toronto, Canada). BHFHP was monitored at 347.0 m/z (MH+). Data were processed using API2000 standard software MacQuan v1.6 from PE Sciex (Foster City, CA, USA).

Data analysis

Unless otherwise noted, results are shown as means±s.e.mean and significant differences between means were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett's multiple comparison test (two tailed). Data from the experiments measuring LRR are expressed as median and interquartile range and differences between each of the doses and vehicle was calculated with Mann–Whitney U-tests (one tailed).

Materials

The rac-BHFF, (+)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one ((+)-BHFF), (−)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one ((−)-BHFF), 2-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxy-phenyl)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-hydroxy-propionic acid, sodium salt (BHFHP) and 5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-1,3-dihydro-indol-2-one (BHFI) were synthesized at F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd (Malherbe et al., 2007). CGP7930 was synthesized in-house (courtesy of Dr Synèse Jolidon, PRBD-C, F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). Baclofen (G-013), GABA (A2129), guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP; G-7252), GTPγS (G-8634) and probenecid (catalogue no. P8761) were obtained from Sigma. GTPγ[35S] (specific activity, 1000 Ci mmol−1; SJ1308) was from Amersham Biosciences. Hanks' balanced salt solution (10 × ) (catalogue no. 14065-049) and HEPES (catalogue no. 15630-056) were purchased from Invitrogen.

Results

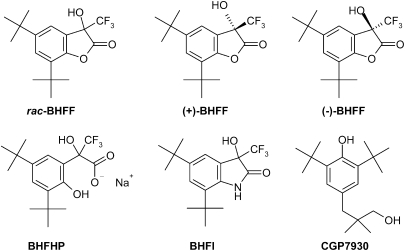

Discovery of 5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one derivatives as GABAB enhancers

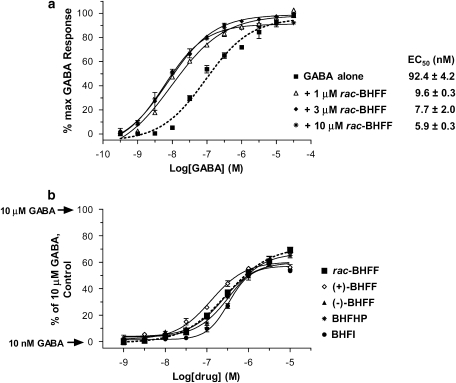

In CHO-Gα16 cells stably expressing hGABAB(1a,2a) receptors, GABA elicited a concentration-dependent increase in intracellular free calcium [Ca2+]i. A functional high-throughput screen FLIPR assay was specifically designed for the detection of compounds (enhancers) that could induce a leftward shift of the GABA concentration–response curve. The compound, 5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one (BHFF) (Figure 1) was then identified as a high-throughput screen hit during a screening survey of the Roche small-molecule corporate library using GABA-shift FLIPR assay and CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) line 10-14 cells. As seen in Figure 2a, BHFF at 1, 3 and 10 μM caused a leftward shift in the GABA concentration–response curve with decreases in the GABA EC50 values by 9.6-, 12.0- and 15.7-fold, respectively, but with no effects on the GABA maximal response.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of GABAB receptor allosteric enhancers, BHFF derivatives and CGP7930.

Figure 2.

Effect of allosteric enhancers on GABA-evoked [Ca2+]i. (a) Concentration–response curves for GABA in the absence and in the presence of 1, 3 and 10 μM rac-BHFF. (b) Concentration–response curves of rac-BHFF derivatives in the presence of 10 nM GABA (∼EC10 value). GABA-evoked response in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line (10-14) stably expressing hGABAB(1a,2a) receptor and Gα16 was generated using the Ca2+-sensitive dye, Fluo-4AM and a Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader (FLIPR-96). Responses were measured as peak increase in fluorescence minus basal, normalized to the maximal stimulatory effect induced by 10 μM GABA alone (considered 100%) and 10 nM GABA alone (considered 0%). Each curve represents mean±s.e.mean (bars) of the three concentration–response measurements (each performed in triplicate) from three independent experiments.

A chiral centre is present in rac-BHFF and we have separated the enantiomers (+)-BHFF and (−)-BHFF (Figure 1). Under our analytical conditions, during pharmacokinetic studies in mouse plasma after p.o. administration of rac-BHFF, only the hydrolysed form BHFHP (Figure 1) could be measured. For comparison, we have also prepared a hydrolytically stable lactam analogue of BHFF, encoded BHFI (Figure 1) in which the oxygen atom was replaced by a NH. The concentration–response curves for the potentiation of 10 nM (GABA EC10 value) GABA-evoked [Ca2+]i responses by rac-BHFF, (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF, BHFHP and BHFI at the hGABAB(1a,2a) receptor are shown in Figure 2b, and their derived EC50, Emax (% of 10 μM GABA alone) and nH values in Table 1. The (+)-enantiomer is more potent than the (−)-enantiomer. As seen in Table 1, the rac-BHFF and its hydroxy-acid form (BHFHP) are equipotent as enhancers at GABAB receptor.

Table 1.

Effect of allosteric enhancers on GABA-evoked [Ca2+]i

| EC50 (nM) | Emax (% of 10 μM GABA) | nH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rac-BHFF | 234.0±13.3 | 65.1±2.7 | 1.0 |

| (+)-BHFF | 80.6±7.7 | 44.5±1.3 | 1.5 |

| (−)-BHFF | 177.0±30.0 | 46.0±1.3 | 1.5 |

| BHFHP | 334.0±19.7 | 60.4±3.3 | 1.2 |

| BHFI | 289.0±12.4 | 49.1±0.8 | 2.1 |

Concentration–response curves were determined in the presence of 10 nM GABA (∼EC10 value) (see Figure 2b). Results are expressed as mean EC50 values and mean maximum enhancing effect (Emax) normalized to the maximal stimulatory effect induced by 10 μM GABA alone (considered 100%) and 10 nM GABA alone (considered 0%). Data are mean±s.e.mean calculated from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Enhancing properties of rac-BHFF derivatives in GTPγ[35S]-binding assay

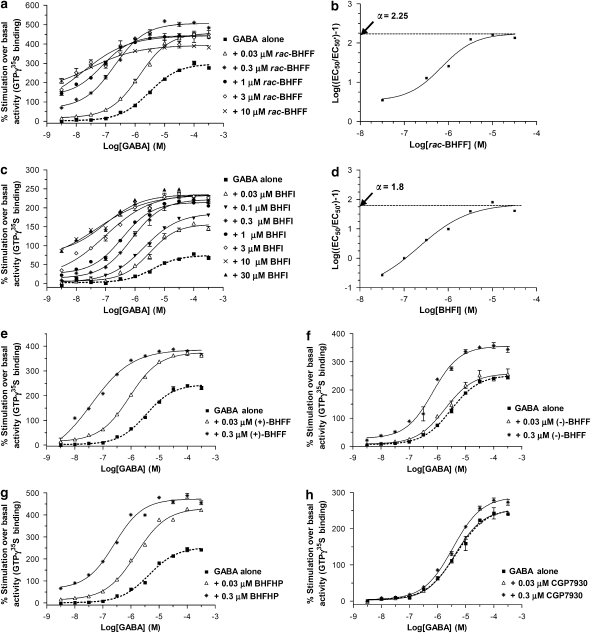

The GABA-induced stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding in the membrane from CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) line 10-14 cells was used to evaluate in greater detail the pharmacology of rac-BHFF derivatives. The GABA concentration–response curves that were performed in the absence and presence of different fixed concentrations of rac-BHFF and BHFI are shown in Figures 3a and c and their EC50, relative Emax (%GABA control) and nH values in Table 2. Increasing fixed concentrations of both compounds induced a pronounced parallel leftward shift of the GABA concentration–response curve with a concomitant increase in maximal GABA stimulation (Emax). As seen in Figures 3a and c and Table 2, rac-BHFF displayed a stronger enhancing effect than its lactam analogue, BHFI. In the presence of 0.3 μM rac-BHFF, the EC50 for GABA decreased by 15.3-fold, whereas the increase in Emax reached its maximum stimulating effect at this concentration (149%) (Figure 3a and Table 2). On the other hand, the presence of 3 μM BHFI caused a decrease in GABA EC50 value by 40.9-fold and an increase in Emax of GABA, which reached its maximum effect (307%) (Figure 3c and Table 2). To characterize the enhancing mode of rac-BHFF and BHFI, the dose ratio (EC50/EC50′) is calculated and plotted in a similar mode to the Schild analysis in Figures 3b and d. EC50 and EC50′ values are determined from GABA concentration–response curves in the absence (GABA alone) and presence of increasing fixed concentrations of enhancer, respectively (Table 2). In Figures 3e–h and Table 2, these analyses (in the presence of 0.03 and 0.3 μM enhancer) of (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF, BHFHP and CGP7930 (the prototype GABAB enhancer) are compared.

Figure 3.

Effects of allosteric enhancers on GABA-induced GTPγ[35S] binding in the membranes from CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) cell line. Concentration–response curves for GABA in the absence and in the presence of 0.03, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 μM rac-BHFF (a), in the absence and in the presence of 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 μM BHFI (c), in the absence and in the presence of 0.03 and 0.3 μM (+)-BHFF (e), (−)-BHFF (f), BHFHP (g) and CGP7930 (h). Schild-like analysis for the enhancing mode of rac-BHFF (b), and of BHFI (d) using the EC50 values derived from plots in (a, c). Each curve represents mean±s.e.mean (bars) of the three concentration–response measurements (each performed in triplicate) from three independent experiments.

Table 2.

A comparison of enhancing characteristics of allosteric enhancers on the potency and efficacy of GABA to stimulate GTPγ[35S] binding to the membranes from CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) cell line

| GABA shift assay | EC50 (nM) | EC50 (GABA)/EC50 (GABA+Enh) | nH | Relative Emax (% GABA control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rac-BHFF | ||||

| GABA alone | 3040.0±265.0 | 0.9 | 100 | |

| GABA+0.03 μM | 1410.0±75.3 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 149.0±5.9 |

| GABA+0.3 μM | 199.0±9.1 | 15.3 | 0.8 | 149.4±8.5 |

| GABA+1.0 μM | 76.4±17.3 | 39.8 | 0.9 | 105.0±23.7 |

| GABA+3.0 μM | 17.4±9.8 | 175.2 | 0.6 | 125.5±59.3 |

| GABA +10.0 μM | 27.5±14.0 | 110.5 | 0.5 | 81.5±7.2 |

| GABA+30.0 μM | 36.6±15.0 | 83.2 | 0.5 | 80.7±15 |

| BHFI | ||||

| GABA alone | 4040.0±688.9 | 1.0 | 100.0 | |

| GABA+0.03 μM | 3180.0±429.0 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 208.9±4.3 |

| GABA+0.3 μM | 779.0±48.4 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 289.7±6.5 |

| GABA+1.0 μM | 367.0±29.4 | 11.0 | 0.8 | 262.5±5.0 |

| GABA+3.0 μM | 98.7±9.8 | 40.9 | 0.6 | 307.3±7.6 |

| GABA+10.0 μM | 49.3±17.6 | 81.9 | 0.5 | 249.7±17.6 |

| GABA+30.0 μM | 95.7±12.0 | 42.2 | 0.7 | 217.2±10.5 |

| (+)-BHFF | ||||

| GABA alone | 3450.0±270.0 | 0.9 | 100.0 | |

| GABA+0.03 μM | 875.0±55.0 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 149.0±2.7 |

| GABA+0.3 μM | 40.0±10.0 | 87.3 | 0.6 | 181.0±1.0 |

| (−)-BHFF | ||||

| GABA alone | 3090.0±163.0 | 0.9 | 100.0 | |

| GABA+0.03 μM | 1900.0±169.0 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 101.8±6.0 |

| GABA+0.3 μM | 691.0±141.0 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 133.2±7.2 |

| BHFHP | ||||

| GABA alone | 4380.0±96.3 | 0.9 | 100.0 | |

| GABA+0.03 μM | 1530.0±54.2 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 165.3±1.8 |

| GABA+0.3 μM | 258.0±5.0 | 17.0 | 0.9 | 162.0±1.0 |

| CGP7930 | ||||

| GABA alone | 4500.0±286.0 | 0.8 | 100.0 | |

| GABA+0.03 μM | 4120.0±187.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 99.4±1.3 |

| GABA+0.3 μM | 3470.0±83.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 112.6±5.1 |

Abbreviation: Enh, enhancer.

Concentration–response curves for GABA were measured in the absence and presence of various concentrations of allosteric enhancers (see Figure 3a, c, e–h). The EC50, Hill coefficient (nH) and relative Emax (% GABA control) values of GABA are mean±s.e.mean, calculated from three independent experiments each performed in triplicate.

To determine the enhancing potency, the concentration–response curves of rac-BHFF and BHFI in the absence and presence of increasing fixed concentrations of GABA are shown in Figures 4a and b and the calculated EC50 and nH values in Table 3. In this high expressing hGABAB(1a,2a) receptor cell line, rac-BHFF and BHFI stimulated GTPγ[35S] binding in the membrane from this stable cell line in the absence of exogenous GABA with EC50 values of 0.725 and 6.39 μM, respectively. Addition of fixed concentrations of GABA caused parallel leftward shift in the concentration–response curves of both enhancers along with the large decreases in the enhancer EC50 values (Figures 4a and b and Table 3). Similarly, the concentration–response curves of (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF, BHFHP and CGP7930, in the absence and presence of 1 μM GABA, were compared in the Figures 4c–f and Table 3. In the absence of exogenous GABA, (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF and BHFHP displayed intrinsic activities in the membrane of hGABAB(1a,2a) cell line 10-14 with the EC50 values of 0.556, 1.33 and 0.712 μM and once more the addition of 1 μM GABA resulted in the leftward shift of the enhancer's concentration–response curve. CGP7930 appears to be a weaker enhancer in comparison to rac-BHFF derivatives, the stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding with CGP7930 was only observed in the presence of 1 μM GABA (EC50=4.18 μM; Figure 4f and Table 3), which is in good agreement with the EC50 value reported previously (Urwyler et al., 2001). As observed above in the FLIPR assay, in the GTPγ[35S]-binding assay, the (+)-enantiomer exhibited a more pronounced enhancing effect than that of the (−)-enantiomer and that of rac-BHFF. However, rac-BHFF and its hydroxy-acid form BHFHP showed similar enhancing effects.

Figure 4.

A comparison of concentration–response curves in the GTPγ[35S]-binding assay for rac-BHFF (a) and BHFI (b) in the absence and in the presence of 0.2, 0.6, 1, 6 and 20 μM GABA, and for (+)-BHFF (c), (−)-BHFF (d), BHFHP (e) and CGP7930 (f) in the absence and in the presence of 1 μM GABA. Each curve represents mean±s.e.mean (bars) of the three concentration–response measurements (each performed in triplicate) from three independent experiments.

Table 3.

Effect of allosteric enhancers alone and in the presence of various concentrations of GABA on the stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding to the membranes from CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) cell line

| EC50 (nM) | EC50 (Enh)/EC50 (Enh+GABA) | nH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rac-BHFF alone | 725.0±28.3 | 1.2 | |

| rac-BHFF+0.2 μM GABA | 138.0±2.1 | 5.3 | 1.3 |

| rac-BHFF+0.6 μM GABA | 110.0±3.8 | 6.6 | 0.9 |

| rac-BHFF+1.0 μM GABA | 50.0±7.4 | 12.3 | 1.0 |

| rac-BHFF+6.0 μM GABA | 23.1±3.5 | 31.4 | 1.1 |

| rac-BHFF+20.0 μM GABA | 20.3±1.6 | 35.7 | 1.6 |

| BHFI alone | 6390.0±1111.4 | 0.8 | |

| BHFI+0.2 μM GABA | 915.0±43.0 | 7.0 | 0.8 |

| BHFI+0.6 μM GABA | 438.0±61.6 | 14.6 | 0.8 |

| BHFI+1.0 μM GABA | 299.0±15.4 | 21.3 | 0.8 |

| BHFI+6.0 μM GABA | 134.0±8.4 | 47.6 | 0.7 |

| BHFI+20.0 μM GABA | 34.0±11.7 | 188.0 | 0.7 |

| (+)-BHFF alone | 556.0±4.3 | 1.0 | |

| (+)-BHFF+1.0 μM GABA | 29.7±4.0 | 18.7 | 1.0 |

| (−)-BHFF alone | 1330.0±57.0 | 1.3 | |

| (−)-BHFF+1.0 μM GABA | 142.0±3.8 | 9.4 | 1.3 |

| BHFHP alone | 712.0±23.8 | 1.6 | |

| BHFHP+1.0 μM GABA | 48.0±2.8 | 14.8 | 1.1 |

| CGP7930 alone | No effect | ||

| CGP7930+1.0 μM GABA | 4180.0±957.0 | 1.0 |

Concentration–response curves were measured in the absence and presence of 0.2, 0.6, 1, 6 and 20 μM GABA for rac-BHFF and BHFI, and in the absence and presence of 1 μM GABA for (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF, BHFHP and CGP7930 (see Figure 4). The EC50 and nH values are mean±s.e.mean, calculated from three independent experiments each performed in triplicate.

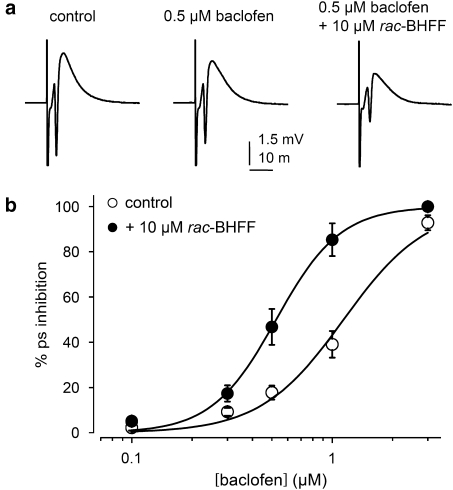

Enhancing effect of rac-BHFF on inhibition of PS by baclofen

The potentiation by rac-BHFF of the inhibition of PS by baclofen was investigated in rat hippocampal slices. PS was generated every 30 s and increasing concentrations of baclofen were applied to the slice. After washout of baclofen, rac-BHFF was first applied for 15 min alone and then co-applied with increasing concentrations of baclofen. Baclofen induced a concentration-dependent decrease in PS amplitude with a complete inhibition being reached at 3 μM baclofen (Figure 5). When rac-BHFF (10 μM) was applied alone to the slice, no change in PS amplitude was observed. In the presence of rac-BHFF, the concentration–response curve for PS inhibition by baclofen was shifted to the left (Figure 5b). The pIC50 values for the baclofen effect on PS inhibition in the absence and presence of 10 μM rac-BHFF were 5.94±0.05 and 6.27±0.06 (n=7), respectively. Therefore, rac-RO4650937 acted as a positive modulator of the inhibitory effect of baclofen on PS in rat hippocampal slices.

Figure 5.

Effect of rac-BHFF on population spike (PS) inhibition by baclofen. (a) Representative PS obtained in the same hippocampal slice and evoked in the absence and presence of baclofen and rac-BHFF. (b) Concentration–response curves of baclofen for inhibition of PS generated in the absence and presence of rac-BHFF.

Selectivity

The pharmacological specificity of rac-BHFF was confirmed by testing it in radioligand-binding assays in a broad CEREP screen (Paris, France) (www.cerep.fr). rac-BHFF was considered inactive (<50% activity at 10 μM) at all targets tested with the exception of the cholecystokinin (CCK) A receptor, where it caused a 86% displacement of specific binding at 10 μM. However, subsequent concentration–response curve of rac-BHFF showed an IC50=4.1 μM, Ki=3.1 μM, nH=1.1 in the binding assay at hCCKA receptor. Interestingly, in the non-selective GABA-binding assay, rac-BHFF (10 μM) enhanced [3H]GABA-specific binding (SB) in rat cerebral cortex by twofold (Table 4). As rac-BHFF was inactive at GABAA receptor in the [3H]flunitrazepam-binding assay, the [3H]GABA SB enhancement seen in the rat cerebral cortex could be due to the enhancing effect of rac-BHFF on GABAB receptors present in this region of brain. Furthermore, with various functional models, it was found that rac-BHFF at concentrations up to 10 μM was devoid of any activity as agonist/enhancer or antagonist at rat mGlu1 (FLIPR assay), mGlu2 (GTPγ35S-binding assay), mGlu5 (FLIPR assay), mGlu7 (cAMP accumulation assay) and mGlu8 (FLIPR assay) receptors.

Table 4.

CEREP (www.cerep.fr) binding screen undertaken to determine the pharmacological activity of rac-BHFF

| Binding assay target | Reference compound | % of control (10 μM) SB (mean) | Binding assay target | Reference compound | % of control (10 μM) SB (mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 (h) | DPCPX | 91.7 | NK3 (h) | SB 222200 | 79.1 |

| A2A (h) | NECA | 111.8 | Y1 (h) | NPY | 97.2 |

| A3 (h) | IB-MECA | 63.1 | Y2 (h) | NPY | 95.7 |

| α1 (non-selective) | Prazosin | 99.5 | NT1 (h) (NTS1) | Neurotensin | 110.3 |

| α2 (non-selective) | Yohimbine | 101 | δ2 (h) (DOP) | DPDPE | 86.6 |

| β1 (h) | Atenolol | 106.7 | κ(KOP) | U 50488 | 88.3 |

| β2 (h) | ICI 118551 | 97.2 | μ (h) (MOP) (agonist site) | DAMGO | 90.3 |

| AT1 (h) | Saralasin | 107.4 | ORL1 (h) (NOP) | Nociceptin | 105.3 |

| BZD (central) | Diazepam | 102 | TP (h) (TXA2/PGH2) | U 44069 | 85.9 |

| B2 (h) | NPC 567 | 102.1 | 5-HT1A (h) | 8-OH-DPAT | 93.6 |

| CB1 (h) | CP 55940 | 86.9 | 5-HT1B | Serotonin | 95.8 |

| CCKA (h) (CCK1) | CCK-8s | 13.5 | 5-HT2A (h) | Ketanserin | 100.8 |

| D1 (h) | SCH 23390 | 92.5 | 5-HT3 (h) | MDL 72222 | 92.4 |

| D2S (h) | (+)Butaclamol | 99.4 | 5-HT5A (h) | Serotonin | 90 |

| ETA (h) | Endothelin-1 | 120.2 | 5-HT6 (h) | Serotonin | 95.9 |

| GABA (non-selective) | GABA | 208.8 | 5-HT7 (h) | SEROTONIN | 104.4 |

| GAL2 (h) | Galanin | 100.3 | sst (non-selective) | Somatostatin-14 | 98.7 |

| CXCR2 (h) (IL-8B) | IL-8 | 97.4 | VIP1 (h) (VPAC1) | VIP | 103.9 |

| CCR1 (h) | MIP-1α | 96.9 | V1a (h) | [d(CH2)51,Tyr(Me)2]-AVP | 96.1 |

| H1 (h) | Pyrilamine | 101.3 | Ca2+ channel (L, verapamil site) (phenylalkylamines) | D 600 | 95.5 |

| H2 (h) | Cimetidine | 88.6 | K+V channel | α-Dendrotoxin | 101.3 |

| MC4 (h) | NDP-α-MSH | 102.9 | SK+Ca channel | Apamin | 105.7 |

| MT1 (h) | Melatonin | 91.3 | Na+ channel (site 2) | Veratridine | 97.3 |

| M1 (h) | Pirenzepine | 85.7 | Cl− channel | Picrotoxinin | 55.7 |

| M2 (h) | Methoctramine | 117.5 | NE transporter (h) | Protriptyline | 69.8 |

| M3 (h) | 4-DAMP | 104 | DA transporter (h) | BTCP | 77.9 |

| NK2 (h) | [Nle10]-NKA (4-10) | 111 | 5-HT transporter (h) | Imipramine | 105.6 |

Enhancing effect of rac-BHFF in LRR, an in vivo mechanism-based model

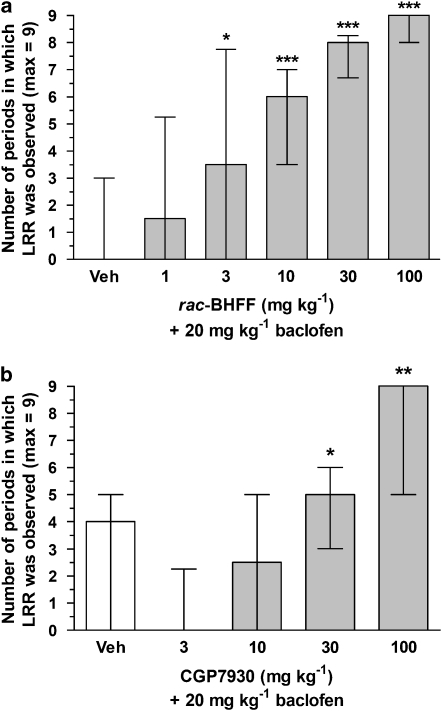

rac-BHFF (1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1, p.o.) significantly increased the LRR effects of a subthreshold dose of baclofen at doses of 3 mg kg−1 and above (Figure 6a). BHFHP, the hydroxy-acid form of rac-BHFF, was also given in the same test at the highest dose (100 mg kg−1, p.o.) and was found to increase significantly the LRR effects of a subthreshold dose of baclofen (data not shown), thereby corroborating the in vitro enhancing effect. CGP7930 (3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1, p.o.) significantly increased the LRR effects of a subthreshold dose of baclofen at 30 and 100 mg kg−1 (Figure 6b). When tested alone at the highest dose (100 mg kg−1, p.o.), rac-BHFF and CGP7930 did not affect LRR, nor did they affect spontaneous locomotor activity.

Figure 6.

Potentiation of baclofen-induced loss of righting reflex (LRR). Male DBA mice received rac-BHFF at doses of 1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1 p.o. (a) or CGP7930 at doses 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1 p.o. (b) 45 min prior to baclofen (20 mg kg−1, i.p.). LRR was measured nine times every 15 min. Data are expressed as median of number of periods in which LRR was observed (max=9)±interquartiles based on 24 animals per dose from three LRR tests. veh, vehicle (10 mL kg−1 of a 4:1:15 mixture containing Cremophor EL, 1,2-propanediol and distilled water). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs vehicle; Mann–Whitney U-test (one tailed).

The effect of rac-BHFF on SIH in mice

rac-BHFF (doses 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1, p.o.) reversed SIH and high significance was reached for 100 mg kg−1 (P<0.001) (Table 5). As shown in Table 5, rac-BHFF had no effect on basal core body temperature T1.

Table 5.

Reversal of stress-induced hyperthermia in mice

| T1 (°C) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rac-BHFF (p.o.) | Veh | 3 mg kg−1 | 10 mg kg−1 | 30 mg kg−1 | 100 mg kg−1 |

| n | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Mean | 37.43 | 37.71 | 37.65 | 37.63 | 37.74 |

| s.e.mean | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| SIH, ΔT (T2−T1) | |||||

| Mean | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.11 |

| s.e.mean | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Significance | *** | ||||

Male NMRI mice received rac-BHFF at doses of 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1 p.o., 1 h prior to T1. Data are mean±s.e.mean based on eight animals per dose.

Veh, vehicle (10 mg kg−1 of a 4:1:15 mixture containing Cremophor EL, 1,2-propanediol and distilled water), ***P<0.001 vs vehicle, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test (two tailed).

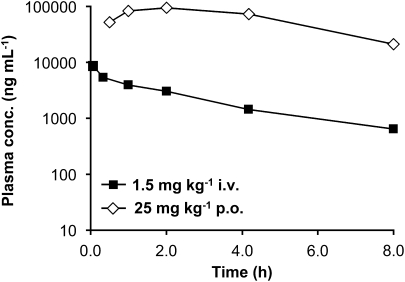

Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic profiles of rac-BHFF

rac-BHFF displayed good physicochemical properties (MW=330; lipophilicity logD of 2.2; pKa of 9.51 and a polar surface area of 40 Å2), except for low thermodynamic solubility (<1 μg mL−1). rac-BHFF does not inhibit major cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (human liver microsomes IC50 values: 3A4 and 2D6: >50 μM; 2C9: 15.5 μM), therefore, it is not thought to exhibit significant drug–drug interaction.

Results from pharmacokinetic experiments in male NMRI mice after single i.v. or p.o. bolus administration are shown in Figure 7. The mean systemic plasma clearance (CL), volume of distribution at steady state and terminal plasma elimination half-life (T1/2) values of rac-BHFF after i.v. administration (1.5 mg kg−1) were 1.26 mL min−1 kg−1, 0.27 L kg−1 and 2.68 h, respectively. Following p.o. administration (25 mg kg−1), the mean Cmax was 93 900 ng mL−1 and the mean absolute p.o. bioavailability of rac-BHFF was 100%. These factors in combination with a very high p.o. bioavailability lead to high plasma concentrations of rac-BHFF both after i.v. as well as p.o. administration. rac-BHFF is highly protein bound (7% free fraction in mouse plasma). The brain to plasma concentration ratio was low (0.04) at 100 mg kg−1 (Table 6). Note that during analysis, quantitative hydrolysis of rac-BHFF to BHFHP occurred; therefore, the measured analyte was BHFHP.

Figure 7.

Pharmacokinetic studies in the mouse with rac-BHFF. Plasma concentration–time curves of the hydrolysed rac-BHFF in male NMRI mice after i.v. or p.o. routes of rac-BHFF administration.

Table 6.

Monitoring of brain and plasma exposure of baclofen and rac-BHFF in male DBA mice (n⩾3) during pharmacological experiments

| Drug treatments, DBA mouse |

Allosteric enhancer |

Baclofen |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brain (ng ml−1) |

Plasma (ng ml−1) |

Brain/plasma |

Brain (ng ml−1) |

Plasma (ng ml−1) |

Brain/plasma | |||||

| Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | |

| 100 mg kg−1 rac-BHFF (p.o.), 1 h+20 mg kg−1 baclofen (i.p.), 15 min (LRR) | 10 715 | 2915 | 261 667 | 31 086 | 0.04 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 20 mg kg−1 baclofen (i.p.), 45 min (DD interaction) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 625 | 110 | 3730 | 330 | 0.17 |

| 20 mg kg−1 baclofen (i.p.), 45 min+10 mg kg−1 rac-BHFF (p.o.), 2 h (DD interaction) | 681 | 129 | 29 875 | 2707 | 0.02 | 674 | 183 | 4328 | 1366 | 0.16 |

| 20 mg kg−1 baclofen (i.p.), 45 min+100 mg kg−1 rac-BHFF (p.o.), 2 h (DD interaction) | 14 628 | 2935 | 354 000 | 19 166 | 0.04 | 629 | 237 | 3568 | 1344 | 0.18 |

| 20 mg kg−1 baclofen (i.p.), 45 min+100 mg kg−1 CGP7930 (p.o.), 2 h (DD interaction) | CND | CND | CND | CND | CND | 723 | 212 | 4967 | 1690 | 0.15 |

Abbreviations: CND, cannot be determined; DD, drug–drug; NA, not assessed.

The measured analytes were baclofen and hydrolyzed rac-BHFF analyzed at the indicated time points after administration.

Monitoring of baclofen and rac-BHFF exposure

To exclude any drug–drug interaction between rac-BHFF and baclofen or CGP7930 and baclofen, the plasma and brain exposure of baclofen were monitored during various pharmacological experiments in male DBA mice. As seen in Table 6, the plasma and brain concentrations of baclofen did not change between tests, suggesting that there is no interaction of baclofen with the co-administered compounds. In addition, plasma as well as brain tissue showed clear exposure towards rac-BHFF. The stability of the lactone ring of rac-BHFF as a function of pH was not investigated in vitro either in water or in biological fluids such as blood plasma. However, chemical hydrolysis of the lactone ring of rac-BHFF occurred readily with two equivalents of 1 N NaOH in dioxane at 20 °C to give a disodium salt in solution from which a mono sodium salt (BHFHP) could be isolated by extraction with toluene. Interestingly, treatment of BHFHP with two equivalents of 1 N HCl readily gave rac-BHFF rather than the hydroxyl-acid form of BHFHP, in other words, lactone formation is a spontaneous process at neutral or slightly acidic pH (Alker AM et al., unpublished data). In blood plasma, the action of esterases and protein binding may have contributed to the prevalence of BHFHP over rac-BHFF. Therefore, because of spontaneous conversion of rac-BHFF to BHFHP and vice versa, it is expected that the mice were exposed to a mixture of rac-BHFF and its hydroxy-acid form in the in vivo studies. Because of technical limitations of our analytical method, we could not detect the brain and plasma levels of CGP7930, but as seen in Table 6, treatment with CGP7930 did not alter the levels of baclofen in plasma or brain.

Discussion

On the basis of the activity of baclofen, a selective GABAB agonist that was reported to attenuate post-traumatic stress and panic disorders in patients (Breslow et al., 1989; Drake et al., 2003) and on the reported anxiety-like behaviour of GABAB receptor-deficient mice (Mombereau et al., 2004, 2005), GABAB receptors have been implicated in the modulation of anxiety, pain and mood disorders. To avoid the numerous side effects associated with baclofen, development of allosteric enhancers of GABAB receptors may provide an alternative therapeutic approach to modulation of GABAB receptor function. Until now, CGP7930, its aldehyde analogue CGP13501 and GS39783 were the only positive allosteric modulators reported (Urwyler et al., 2001, 2003). Indeed GS39783 was shown to exhibit anxiolytic-like effects in several rodent models of anxiety (Cryan et al., 2004). A recent preclinical study with CGP7930 has shown both antidepressant- and anxiolytic-like effects (Frankowska et al., 2007).

Here, we have introduced a new series of potent allosteric enhancers of GABAB receptors. In the GABA-induced stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding to CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) cell membranes, the presence of 0.3 μM rac-BHFF (a racemate), (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF (the pure enantiomers), BHFHP (hydroxy acid) and BHFI (lactam analogue) shifted the GABA concentration–response curve to the left, an effect that resulted in large increases in both GABA potency (by 15.3-, 87.3-, 4.5-, 17- and 5.2-fold) and efficacy (149, 181, 133, 162 and 290%), respectively. The (+)-enantiomer-BHFF was found to be the most potent enhancer among this series. The Schild analyses of rac-BHFF and BHFI were consistent with an allosteric-enhancing mode (non-competitive) with positive cooperativity factors (plateau=α) of 2.25 and 1.8, respectively (Figures 3b and d). The rac-BHFF and its derivatives elicited intrinsic activity in the absence of exogenous GABA in the stable CHO-Gα16-hGABAB(1a,2a) cell system. Constitutive activity of recombinant GABAB receptor resulting from high expression level (Bmax=32.6 pmol per mg protein) might be considered to be responsible for this intrinsic activity, as in a physiologically native system such as hippocampal slices, rac-BHFF (10 μM) did not exhibit any effect by itself nor was it active alone in in vivo. Interestingly, similar intrinsic activity was observed previously with the mGlu1 receptor enhancer RO 67-7476, which displayed intrinsic activity in the absence of exogenous glutamate in cells expressing very high levels of mGlu1 receptors, but was devoid of any effect when applied alone in hippocampal CA3 neurons (Knoflach et al., 2001). However, the presence of 1 μM GABA caused huge increases in the potency of rac-BHFF, (+)-BHFF, (−)-BHFF, BHFHP and BHFI by 12.3-, 18.7-, 9.4-, -14.8- and 21.3-fold, respectively.

The enhancing activity of rac-BHFF on the native receptor was assessed under physiological conditions in rat hippocampal slices using the baclofen-induced inhibition of PS of CA1 pyramidal cells. Baclofen inhibited the PS by activating postsynaptic GABAB receptors expressed on dendrites of pyramidal cells in a concentration-dependent manner. The presence of 10 μM rac-BHFF had no effect by itself on PS, but it shifted the baclofen concentration–response curve to the left. Therefore, rac-BHFF acted as a positive modulator of the inhibitory effect of baclofen on the PS mediated by modulating the postsynaptic GABAB receptors in the rat hippocampal CA1 area. Interestingly, recent studies using isoform-deficient mice have demonstrated that the GABAB(1a) and GABAB(1b) isoforms are differentially involved in the pre- and postsynaptic transmission; the postsynaptic inhibition of Ca2+ spikes is mediated by GABAB(1b), whereas presynaptic inhibition of GABA release is mediated by GABAB(1a) (Perez-Garci et al., 2006; Vigot et al., 2006). The two isoforms differ only in the presence or absence of a pair of sushi repeats at their extracellular amino-terminal domain. Given the fact that it has already been shown that 7TMD of GABAB(2) is activated directly by CGP7930 (Binet et al., 2004), the positive allosteric modulators are most likely to bind to a novel allosteric site located within the 7TMD region. Thus, one expects GABAB-positive modulators to enhance the synaptic transmission mediated by both GABAB(1a) and GABAB(1b) isoforms. However in this context, CGP7930 has been shown to enhance selectively the baclofen-induced modulation of synaptic inhibition without any significant effect on the synaptic excitation, an action that indicated a differential synaptic modulation by CGP7930 (Chen et al., 2006).

Once the positive allosteric modulator properties in vitro in cellular and native tissue had been established, the next question was whether this in vitro enhancing effect would translate to in vivo behavioural effects. Recently, Carai et al. (2004) showed that CGP7930 enhanced the effects of baclofen on the LRR in the absence of effects of the compound alone. We used a similar paradigm and confirmed the effects of CGP7930 at similar doses. We then tested rac-BHFF and found similar enhancing effects but at lower doses (significance starting at 3 mg kg−1, p.o.), which was surprising given the low brain to plasma ratio of this compound. However, given the absence of increases in baclofen levels by rac-BHFF, and because the LRR effect of baclofen is thought to be caused by central effects (cf. Jacobson and Cryan, 2005), we think that the observed brain levels were sufficient to enhance GABAB receptor stimulation by baclofen. Of note is the specificity of enhancing effect of rac-BHFF. When measured alone at the highest dose (100 mg kg−1, p.o.) over 3 h (starting 60 min after administration), no sign of LRR was observed even when determined with the most sensitive parameter (LRR>1 s). Likewise, rac-BHFF (100 mg kg−1, p.o.) alone was devoid of any effect on spontaneous locomotor activity (measured during 90 min). rac-BHFF (at doses 3, 10, 30 and 100 mg kg−1, p.o.) did not modify core body temperature measured 1 h after administration.

Then, it remained to be seen whether the in vivo enhancing properties would also be expressed when rac-BHFF was administered alone, consequently we tested it in SIH, which is considered to be an autonomic measure of anticipatory anxiety in mice (Bouwknecht et al., 2007). The rac-BHFF produced physiological effects predictive of anxiolytic efficacy in this test that supported the assumption that it enhanced endogenous GABA in relevant brain areas. Indeed, similar effects were observed with CGP7930 (Nicolas L et al., unpublished data). In the current study, a direct comparison was made between the in vitro and in vivo enhancing properties of rac-BHFF and CGP7930 (Urwyler et al., 2001). At a concentration of 0.3 μM, rac-BHFF increased the potency and the maximal efficacy of GABA by 15.3-fold and 149%, respectively, compared with increases of only 1.3-fold and 113% for CGP7930. In the presence of 1 μM GABA, rac-BHFF had a potency of 0.050 μM (EC50 value), whereas the CGP7930 potency was 4.18 μM. Similarly in the mechanism-based LRR test, rac-BHFF displayed its enhancing effect at much lower dose than that of CGP7930. Therefore compared with CGP7930, rac-BHFF appears to possess a much stronger enhancing property.

With respect to pharmacokinetic properties of rac-BHFF and its hydroxy-acid BHFHP, it should be noted that rac-BHFF is hydrolysed under our analytical conditions; therefore, we cannot determine the ratio of the two forms present during pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic monitoring in the mouse. Because of rapid interconversion, we assume that rac-BHFF and its hydroxy-acid BHFHP are present in vivo, and as both forms displayed a similar level of enhancing activity, both may contribute to the observed in vivo effects. The single dose pharmacokinetic results revealed that BHFF/BHFHP has ideal pharmacokinetic properties for a peripherally acting drug, with high bioavailability, high plasma concentrations, low metabolic clearance and a low volume of distribution. Analysis of the samples from the pharmacodynamics monitoring of the LRR experiment revealed that although very high concentrations of compound were detected in the brain samples, the comparison with the plasma samples gave a the brain/plasma ratio of 0.04 (at 100 mg kg−1, p.o.), which is judged to be very low. Nevertheless, the measured brain levels were significantly above the GABAB EC50 for the compound (due to the extremely high plasma concentration) and it is likely that sufficient levels of rac-BHFF/BHFHP do indeed reach specific relevant brain regions to account for the observed in vivo activity in the LRR and SIH experiments. The presence of GABAB receptors has been confirmed in the peripheral nervous system such as spleen, lung, liver, intestine, stomach, oesophagus and urinary bladder (Calver et al., 2000; Vacher and Bettler, 2003). Interestingly, baclofen inhibits overactive bladder (bladder function is under tonic GABAB control), gastroesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, cough and asthma (Cange et al., 2002; Pehrson et al., 2002; Piqueras et al., 2004). Therefore, GABAB enhancers, such as rac-BHFF with a high p.o. bioavailability, might also have potential therapeutic application as peripherally active GABAB enhancers.

In summary, we have shown that rac-BHFF derivatives are potent GABAB enhancers capable of enhancing the GABA and baclofen activities at recombinant and native GABAB receptors. Furthermore, rac-BHFF displayed robust in vivo activity in both a mechanism-based paradigm and a model of anxiety. Therefore, rac-BHFF derivatives should provide an important tool to elucidate the pathophysiological roles played by GABAB receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Hassen Ratni for his earlier chemistry results, and Catherine Diener, Sean Durkin, François Grillet, Nadine Nock and Marie Claire Pflimlin for their expert technical assistance. We are very grateful to Drs Silvia Gatti, Lothar Lindemann and Christoph Ullmer for the selectivity test at mGlu receptors.

Abbreviations

- 7TMD

seven-transmembrane domain

- CGP7930

2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-phenol

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- FLIPR

Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader

- GPCRs

G-protein-coupled receptors

- LRR

loss of righting reflex

- mGlu

metabotropic glutamate

- PS

population spike

- rac-BHFF

(R,S)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one

- SIH

stress-induced hyperthermia

Conflict of interest

We are employees of F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

References

- Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Mosbacher J, Gassmann M. Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABA(B) receptors. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:835–867. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binet V, Brajon C, Le Corre L, Acher F, Pin JP, Prezeau L. The heptahelical domain of GABA(B2) is activated directly by CGP7930, a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA(B) receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29085–29091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400930200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwknecht JA, Olivier B, Paylor RE. The stress-induced hyperthermia paradigm as a physiological animal model for anxiety: a review of pharmacological and genetic studies in the mouse. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:41–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG. GABA(B) receptor: a site of therapeutic benefit. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow MF, Frankhauser MP, Potter RL, Meredith KE, Misiaszek J, Hope DG. Role of g-aminobutyric acid in antipanic drug efficacy. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:353–356. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calver AR, Medhurst AD, Robbins MJ, Charles KJ, Evans ML, Harrison DC, et al. The expression of GABA(B1) and GABA(B2) receptor subunits in the CNS differs from that in peripheral tissues. Neuroscience. 2000;100:155–170. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cange L, Johnsson E, Rydholm H, Lehmann A, Finizia C, Lundell L, et al. Baclofen-mediated gastro-oesophageal acid reflux control in patients with established reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:869–873. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carai MA, Colombo G, Froestl W, Gessa GL. In vivo effectiveness of CGP7930, a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;504:213–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Menendez-Roche N, Sher E. Differential modulation by the GABAB receptor allosteric potentiator 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-phenol (CGP7930) of synaptic transmission in the rat hippocampal CA1 area. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1170–1177. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.099176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Phillips K, Minton G, Sher E. GABA(B) receptor modulators potentiate baclofen-induced depression of dopamine neuron activity in the rat ventral tegmental area. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:926–932. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Kelly PH, Chaperon F, Gentsch C, Mombereau C, Lingenhoehl K, et al. Behavioral characterization of the novel GABAB receptor-positive modulator GS39783 (N,N′-dicyclopentyl-2-methylsulfanyl-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4,6-diamine): anxiolytic-like activity without side effects associated with baclofen or benzodiazepines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:952–963. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RG, Davis LL, Cates ME, Jewell ME, Ambrose SM, Lowe JS. Baclofen treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:1177–1181. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankowska M, Filip M, Przegaliñski E. Effects of GABAB receptor ligands in animal tests of depression and anxiety. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:645–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez T, Prezeau L, Milioti G, Franek M, Joly C, Froestl W, et al. Mapping the agonist-binding site of GABAB type 1 subunit sheds light on the activation process of GABAB receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41166–41174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjoni T, Desrayaud S, Imobersteg S, Urwyler S. The positive allosteric modulator GS39783 enhances GABA(B) receptor-mediated inhibition of cyclic AMP formation in rat striatum in vivo. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1416–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerland LG, Garrett JE, Hung BC, Levinthal C, Nemeth EF. Allosteric activation of the Ca2+ receptor expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes by NPS 467 or NPS 568. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:1083–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlickova M, Prezeau L, Duthey B, Bettler B, Pin JP, Blahos J. The intracellular loops of the GB2 subunit are crucial for G-protein coupling of the heteromeric gamma-aminobutyrate B receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:343–350. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DR, Bowery NG. 3H-Baclofen and 3H-GABA bind to bicuculline-insensitive GABA B sites in rat brain. Nature. 1981;290:149–152. doi: 10.1038/290149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LH, Cryan JF. Differential sensitivity to the motor and hypothermic effects of the GABA B receptor agonist baclofen in various mouse strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:688–699. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Baez M, Jagdmann GE, Jr, Britton TC, Large TH, Callagaro DO, et al. Discovery of allosteric potentiators for the metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor: synthesis and subtype selectivity of N-(4-(2-methoxyphenoxy)phenyl)-N-(2,2,2-trifluoroethylsulfonyl)pyrid-3-ylmethylamine. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3189–3192. doi: 10.1021/jm034015u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Huggel K, Heid J, Flor PJ, Bischoff S, Mickel SJ, et al. Expression cloning of GABA(B) receptors uncovers similarity to metabotropic glutamate receptors [see comments] Nature. 1997;386:239–246. doi: 10.1038/386239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Malitschek B, Schuler V, Heid J, Froestl W, Beck P, et al. GABA(B)-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature. 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney GG, O'Brien JA, Lemaire W, Burno M, Bickel DJ, Clements MK, et al. A novel selective positive allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 has in vivo activity and antipsychotic-like effects in rat behavioral models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:199–206. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.079244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniazeff J, Galvez T, Labesse G, Pin JP. No ligand binding in the GB2 subunit of the GABA(B) receptor is required for activation and allosteric interaction between the subunits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7352–7361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoflach F, Mutel V, Jolidon S, Kew JN, Malherbe P, Vieira E, et al. Positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate 1 receptor: characterization, mechanism of action, and binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13402–13407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231358298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malherbe P, Knoflach F, Broger C, Ohresser S, Kratzeisen C, Adam G, et al. Identification of essential residues involved in the glutamate binding pocket of the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:944–954. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malherbe P, Masciadri R, Norcross RD, Prinssen E. US patent 2007027204. Chem Abstr Can. 2007;146:184345. [Google Scholar]

- Mombereau C, Kaupmann K, Froestl W, Sansig G, van der Putten H, Cryan JF. Genetic and pharmacological evidence of a role for GABA(B) receptors in the modulation of anxiety- and antidepressant-like behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1050–1062. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombereau C, Kaupmann K, Gassmann M, Bettler B, van der Putten H, Cryan JF. Altered anxiety and depression-related behaviour in mice lacking GABAB(2) receptor subunits. NeuroReport. 2005;16:307–310. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502280-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlemann A, Ward NA, Kratochwil N, Diener C, Fischer C, Stucki A, et al. Determination of key amino acids implicated in the actions of allosteric modulation by 3,3′-difluorobenzaldazine on rat mGlu5 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;529:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partyka A, Kłodziñska A, Szewczyk B, Wieroñska JM, Chojnacka-Wójcik E, Librowski T, et al. Effects of GABAB receptor ligands in rodent tests of anxiety-like behavior. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:757–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrson R, Lehmann A, Andersson KE. Effects of gamma-aminobutyrate B receptor modulation on normal micturition and oxyhemoglobin induced detrusor overactivity in female rats. J Urol. 2002;168:2700–2705. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garci E, Gassmann M, Bettler B, Larkum ME. The GABA(B1b) isoform mediates long-lasting inhibition of dendritic Ca(2+) spikes in layer 5 somatosensory pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2006;50:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrel C, Kessler A, Dauban P, Dodd RH, Rognan D, Ruat M, et al. Positive and negative allosteric modulators of the Ca2+-sensing receptor interact within overlapping but not identical binding sites in the transmembrane domain modeling and mutagenesis of the binding site of Calhex 231, a novel negative allosteric modulator of the extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18990–18997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilc A, Nowak G. GABAergic hypotheses of anxiety and depression: focus on GABA-B receptors. Drugs Today. 2005;41:755–766. doi: 10.1358/dot.2005.41.11.904728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Galvez T, Prezeau L. Evolution, structure, and activation mechanism of family 3/C G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:325–354. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Kniazeff J, Liu J, Binet V, Goudet C, Rondard P, et al. Allosteric functioning of dimeric class C G-protein-coupled receptors. FEBS J. 2005;272:2947–2955. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras L, Martinez V, Symonds E, Butler R, Omari T. Peripheral GABAB agonists stimulate gastric acid secretion in mice: the effect of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen on liquid and solid gastric emptying in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:1038–1048. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren WP, Schoeffter P, Gasparini F, Kuhn R, Gentsch C. Pharmacological and endocrinological characterisation of stress-induced hyperthermia in singly housed mice using classical and candidate anxiolytics ( LY314582, MPEP and NKP608) Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;435:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwyler S, Mosbacher J, Lingenhoehl K, Heid J, Hofstetter K, Froestl W, et al. Positive allosteric modulation of native and recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid(B) receptors by 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-phenol (CGP7930) and its aldehyde analog CGP13501. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:963–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwyler S, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Mosbacher J, Lampert C, Froestl W, et al. N,N′-Dicyclopentyl-2-methylsulfanyl-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4,6-diamine (GS39783) and structurally related compounds: novel allosteric enhancers of gamma-aminobutyric acidB receptor function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:322–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher CM, Bettler B. GABA(B) receptors as potential therapeutic targets. Curr Drug Target CNS Neurol Disord. 2003;2:248–259. doi: 10.2174/1568007033482814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigot R, Barbieri S, Brauner-Osborne H, Turecek R, Shigemoto R, Zhang YP, et al. Differential compartmentalization and distinct functions of GABA(B) receptor variants. Neuron. 2006;50:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]