Abstract

Background and objectives: Niacinamide inhibits intestinal sodium/phosphorus transporters and reduces serum phosphorus in open-label studies. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial was performed for assessment of the safety and efficacy of niacinamide.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Hemodialysis patients with phosphorus levels ≥5.0 mg/dl were randomly assigned to 8 wk of niacinamide or placebo, titrated from 500 to 1500 mg/d. After a 2-wk washout period, patients switched to 8 wk of the alternative therapy. Vitamin D analogs and calcimimetics were held constant; phosphorus binders were not changed unless safety criteria were met.

Results: Thirty-three patients successfully completed the trial. Serum phosphorus fell significantly from 6.26 to 5.47 mg/dl with niacinamide but not with placebo (5.85 to 5.98 mg/dl). A concurrent fall in calcium-phosphorus product was seen with niacinamide, whereas serum calcium, intact parathyroid hormone, uric acid, platelet, triglyceride, LDL, and total cholesterol levels remained stable in both arms. Serum HDL levels rose with niacinamide (50 to 61 mg/dl but not with placebo. Adverse effects were similar between both groups. Among patients who were ≥80% compliant, results were similar, although the decrease in serum phosphorus with niacinamide was more pronounced (6.45 to 5.28 mg/dl) and the increase in HDL approached significance (49 to 58 mg/dl).

Conclusions: In hemodialysis patients, niacinamide effectively reduces serum phosphorus when co-administered with binders and results in a potentially advantageous increase in HDL cholesterol. Further study in larger randomized trials and other chronic kidney disease populations is indicated.

Elevated serum phosphorus contributes to the development of secondary hyperparathyroidism and renal osteodystrophy. In dialysis patients, hyperphosphatemia can lead to metastatic calcifications and is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality (1,2). The majority of dialysis patients require dietary phosphorus restrictions and phosphate binders to control serum phosphorus. Despite these measures, most patients fail to achieve predialysis serum phosphorus levels <5.5 mg/dl (2,3).

Niacinamide (also known as nicotinamide) and niacin are the principle forms of vitamin B3. Despite structural similarities and equivalent nutritional properties, niacinamide and niacin have differing actions and adverse effect profiles. Although niacinamide can cause gastrointestinal discomfort and reportedly lowers platelet counts, it does not cause flushing, which is commonly seen with niacin (4,5). In vitro studies have shown that niacinamide decreases phosphate uptake by inhibiting sodium/phosphorus co-transporters in the renal proximal tubule (Na/Pi2a) and intestine (Na/Pi2b) (6–9). An open-label study of niacinamide in Japanese hemodialysis patients who were not taking phosphorus binders found that dosages up to 1750 mg/d decreased serum phosphorus from 6.9 to 5.4 mg/dl (10). In addition, HDL cholesterol increased and LDL cholesterol declined during the 12 wk of treatment.

Dialysis patients in the United States have poorer phosphorus control and might benefit from the addition of niacinamide to their binder regimen. To evaluate further the effect of oral niacinamide in hemodialysis patients, we performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of hyperphosphatemic hemodialysis patients. For assessment of the additive effects of niacinamide to binder therapy, patients were maintained on their binder regimen throughout the study unless safety criteria for dosage titration were met.

Materials and Methods

Enrollment

This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine and registered in a clinical trials database (NCT00316472, http://www.clintrials.gov). Patients were recruited at two urban dialysis units operated by Washington University School of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, from February 2006 through December 2006. Inclusion criteria were (1) age >18 yr, (2) capacity for informed consent, (3) on long-term hemodialysis >90 d, (4) stable dosage of phosphorus binder(s) during the previous 2-wk period, and (5) serum phosphorus level ≥5.0 mg/dl on the most recent monthly laboratory data. The criteria of a serum phosphorus ≥5.0 mg/dl was used to enroll patients who were within the acceptable range of the current Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) recommendations (serum phosphorus <5.5 mg/dl) but still above the goal of normalizing serum phosphorus levels. Patients were excluded for any of the following criteria: Pregnancy, history of liver disease, active peptic ulcer disease, treatment with carbamazepine, on niacin therapy, more than one missed hemodialysis session in the past 30 d, planned or expected surgical procedure in the ensuing 4 mo, or residency at a nursing home or extended care facility where administration of the study drug may not be appropriately given.

For exclusion of patients with isolated elevations in serum phosphorus, a 2-wk screening phase followed consent. Serum phosphorus was measured before the first dialysis of both weeks. Patients were randomly assigned when the average screening phosphorus was ≥5.0 mg/dl.

Study Medication and Randomization

Niacinamide powder was purchased from Spectrum Chemical Manufacturing Corporation (New Brunswick, NJ). Identical capsules containing 250 mg of niacinamide or placebo were manufactured by a research pharmacist (Stephanie Porto, RPharm, Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, MO). The research pharmacist also randomly assigned patients and provided blinded bottles to the research staff for distribution. Bottles contained sufficient capsules for the next 2 wk on the basis of the patient's randomization order.

Study Design

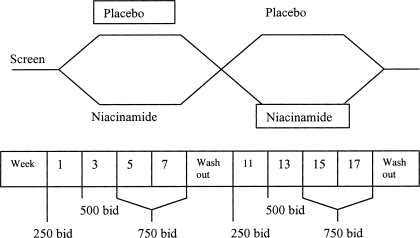

The study was a crossover design (Figure 1). After successful screening, patients were randomly assigned to either placebo or niacinamide. After 8 wk with forced dosage titration (described in the next section), there was a 2-wk washout period, then 8 wk on the alternative therapy. Serum calcium and phosphorus levels were measured weekly. Serum albumin, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), uric acid, and complete blood count were obtained at weeks 1, 9, 11, and 19. Additional complete blood counts were drawn weeks 5 and 15 to monitor for thrombocytopenia. Lipid panels were drawn at weeks 1, 9, and 19. All laboratory values were drawn before dialysis on the first dialysis treatment of each week. Phosphorus binders, vitamin D, paricalcitol, and cinacalcet were continued at the same dosage throughout the study unless changes were necessary for patient safety.

Figure 1.

After a 2-wk screening phase, patients were randomly assigned to 8 wk of niacinamide or placebo with titration from 250 to 750 mg twice daily. A 2-wk washout preceded the switch from niacinamide to placebo or vice versa.

Dosage Titration

Niacinamide or placebo was administered at a starting dosage of one capsule (250 mg) twice daily. The dosage was increased to 500 mg (two capsules) twice daily at week 3 and 750 mg (three capsules) twice daily at week 5. When hypophosphatemia (<3.5 mg/dl) was present, the previous dosage was continued. Titration resumed once the serum phosphorus rose above 3.5 mg/dl. When consecutive serum phosphorus levels were <3.0 mg/dl, study drug was decreased by two capsules per day. Study drug dosage could also be decreased if patients had adverse effects attributable to the study drug. The same dosage titration occurred after washout, beginning in week 11. Pill counts were performed at each dosage titration and at the completion of each study arm.

Safety Stop Points

A decrease in phosphorus binders was permitted when serum phosphorus remained <3.0 mg/dl despite a decrease in the dosage of study drug. An increase in binders, in conjunction with dietary counseling, was permitted when two consecutive phosphorus levels were >7.0 mg/dl or the calcium-phosphorus product was >70 mg2/dl2. When phosphorus binder dosage was changed during the first arm of the study, the new regimen was continued through the remainder of the study.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using two-sample paired-group t test. The primary end point was the change in serum phosphorus from the first to the last week of each arm. Predefined secondary end points were the change in iPTH, calcium, calcium-phosphorus products, uric acid, platelets, and lipid profile parameters (HDL, LDL, triglycerides). An a priori power analysis, assuming an expected phosphorus difference of 1.0 mg/dl with an expected SD of 1.0 mg/dl, showed that 24 patients were needed to achieve 90% power at the 5% significance level. For accounting for dropout and noncompliance, planned recruitment was 40 patients. Upon completion of the study, primary and secondary end points were evaluated for all patients, then repeated among compliant patients, defined by ≥80% use of study pills during each arm.

Data Reporting

The results of this randomized, controlled trial are reported in compliance with the guidelines established by the CONSORT statement (11).

Results

Patient Population

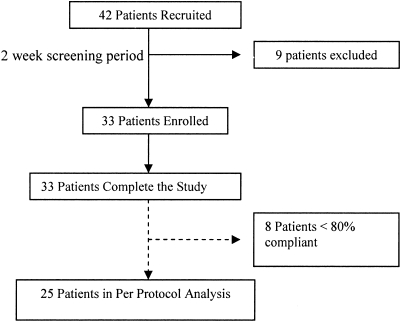

A total of 42 patients underwent screening, and 33 were randomly assigned into the trial. All 33 completed the 20-wk study, and 25 of 33 were ≥80% compliant with medications by pill counts (Figure 2). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1, and baseline data are displayed in Table 2. Laboratory results at the start and completion of placebo and niacinamide arms are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

After the 2-wk screening period, 33 patients were enrolled in the study. All patients completed the study; 25 demonstrated compliance with the study regimen and were included in the per-protocol analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 33)

| Characteristics | % (n) | Average Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| male | 70 (23) | |

| female | 30 (10) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| black | 85 (28) | |

| white | 15 (5) | |

| Medications | ||

| acetylsalicylic acid | 45 (15) | 211 mg/d |

| clopidogrel bisulfate | 6 (2) | 75 mg/d |

| active vitamin D (paricalcitol) | 67 (22) | 5.5 μg/dialysis |

| calcimimetics | 27 (9) | 53 mg/d |

| Binder regimen | ||

| sevelamer hydrochloride | 76 (25) | 7624 mg/d |

| lanthanum carbonate | 12 (4) | 3000 mg/d |

| calcium carbonate | 18 (6) | 1775 mg/d |

| calcium acetate | 27 (9) | 5225 mg/d |

Table 2.

Baseline data

| Parameter | Week 1 Placebo | Week 1 Niacinamide | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 52.6 | 52.6 | |

| Duration on hemodialysis (yr) | 4.4 | 4.4 | |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.35 | 9.39 | 0.81 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 5.85 | 6.26 | 0.27 |

| iPTH (pg/ml) | 288 | 291 | 0.96 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 7.15 | 7.25 | 0.80 |

| Platelet count (1000/mm3) | 216 | 216 | 0.97 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 142 | 142 | 0.92 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 57 | 63 | 0.46 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 55 | 50 | 0.30 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 145 | 146 | 0.96 |

Table 3.

Summary of laboratory findings

| Parameter | Placebo Arm

|

Niacinamide Arm

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 9 | P | Week 1 | Week 9 | P | |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 5.85 ± 1.67 | 5.98 ± 1.40 | NS | 6.26 ± 1.28a | 5.47 ± 1.49a | 0.02a |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.35 ± 0.57 | 9.52 ± 0.76 | NS | 9.39 ± 0.72 | 9.45 ± 0.70 | NS |

| Calcium-phosphorus product (mg2/dl2) | 54.47 ± 14.80 | 56.73 ± 13.22 | NS | 58.72 ± 12.42a | 51.56 ± 13.48a | 0.02a |

| iPTH (pg/ml) | 288 ± 240 | 280 ± 222 | NS | 291 ± 240 | 296 ± 195 | NS |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 7.15 ± 1.67 | 6.88 ± 1.56 | NS | 7.25 ± 1.56 | 6.81 ± 1.50 | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 142 ± 30 | 141 ± 32 | NS | 142 ± 30 | 150 ± 28 | NS |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 57 ± 21 | 59 ± 29 | NS | 63 ± 29 | 60 ± 25 | NS |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 55 ± 19 | 53 ± 20 | NS | 50 ± 17a | 61 ± 21a | 0.04a |

| TG (mg/dl) | 145 ± 74 | 145 ± 86 | NS | 146 ± 70 | 150 ± 84 | NS |

| Platelet (1000/mm3) | 216 ± 68 | 225 ± 57 | NS | 216 ± 53 | 199 ± 55 | NS |

Values changed significantly.

Dosing Characteristics

In accordance with our protocol, the dosages of vitamin D analogs and calcimimetics were not changed for any patient during the study. All patients on vitamin D analogs were treated with paricalcitol. Three patients had a change in phosphorus binders required by our safety stop points. Binders were increased for one patient during placebo (lanthanum carbonate 1000 mg three times daily to 1500 mg three times daily) and one patient during niacinamide (calcium acetate 1334 mg three times daily to 2001 mg three times daily). One patient required a decrease in binder at week 5 of the niacinamide arm (sevelamer 2400 mg three times daily to 1600 mg three times daily). Mean dosages of paricalcitol, calcimimetics, and phosphorus binders are contained in Table 1.

Changes in dialysis prescription were permitted to achieve targets for dialysis adequacy as reflected by monthly KT/V. Among the 31 patients on thrice-weekly hemodialysis, there was no significant difference between KT/V during placebo and niacinamide (1.60 versus 1.56, respectively; P = 0.44). The two patients on hemodialysis four times per week had an average KT/V of 1.1 during placebo and 1.06 during niacinamide, also NS (P = 0.89).

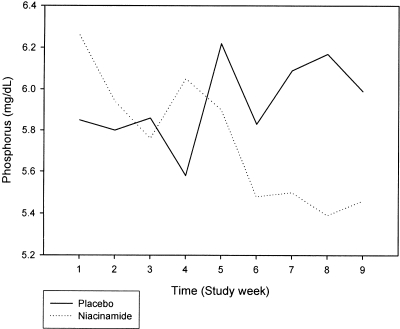

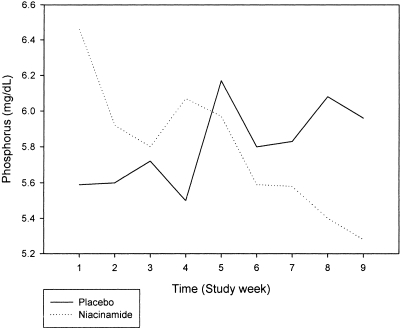

Serum Phosphorus

Among all patients, treatment with placebo resulted in an insignificant rise in serum phosphorus from 5.85 to 5.98 mg/dl (P = 0.73). Treatment with niacinamide resulted in a significant fall in serum phosphorus from 6.26 to 5.47 mg/dl (P = 0.02). The change in serum phosphorus was significantly different between the two groups: The mean change on placebo was +0.13 mg/dl (95% confidence interval [CI] −0.53 to 0.79 mg/dl), whereas the mean change on niacinamide was −0.79 mg/dl (95% CI −0.12 to −1.46 mg/dl; P = 0.05; Figure 3). The largest change in serum phosphorus occurred during the first 2 wk on niacinamide, at a dosage of 250 mg twice daily. Phosphorus levels fell from 6.26 to 5.76 mg/dl during this period but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.14). Dosage titration to the maximum of 750 mg twice daily further reduced serum phosphorus, with levels falling from 5.9 to 5.47 mg/dl during the final 4 wk of the active arm.

Figure 3.

Serum phosphorus levels rose during the 8 wk of the placebo arm (solid line) but decreased significantly during treatment with niacinamide (dotted line). Placebo n = 33; niacinamide n = 33.

Secondary End Points

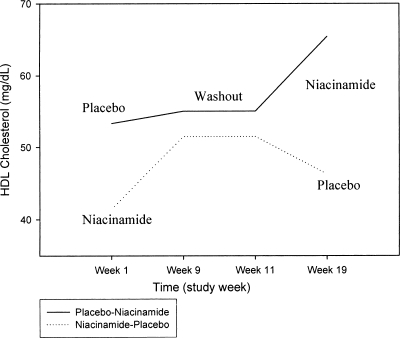

The calcium-phosphorus product decreased significantly (59 to 52 mg2/dl2; P = 0.03) with niacinamide while increasing insignificantly during placebo treatment (54 to 57 mg2/dl2; P = 0.52). There were no significant changes in serum calcium during either treatment arm. Calcium, iPTH, and uric acid levels did not change in either arm, and there were no significant differences in total cholesterol, triglycerides, or LDL cholesterol between arms. HDL cholesterol rose from 50 to 61 mg/dl (P = 0.035) on niacinamide while remaining unchanged on placebo (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of niacinamide on HDL cholesterol levels is shown in both randomization schemes. Among all patients, HDL cholesterol levels increased significantly on niacinamide (50 to 61 mg/dl; P = 0.035). Placebo n = 33; niacinamide n = 33.

Thrombocytopenia has been reported as an adverse effect of niacinamide (4). In our study, the platelet count tended to rise on placebo and fall on niacinamide (+9000 on placebo versus −17,000/mm3 on niacinamide; P = 0.07). Although no patients developed bleeding complications during the study, nine had thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150,000/mm3) with niacinamide and five had thrombocytopenia on placebo. A platelet count of <100,000/mm3 was seen in one patient on niacinamide and two patients on placebo. The trend in platelet counts among patients with thrombocytopenia on niacinamide is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Platelet counts in patients with thrombocytopenia during niacinamidea

| Patient | Niacinamide Arm

|

Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 5 | Week 9 | ||

| 1 | 145b | 297 | 267 | Completed study |

| 2 | 105b | 167 | 169 | Completed study |

| 3 | 135b | 127b | 137b | Placebo arm counts: 135, 98, 111 |

| 4 | 123b | 116b | 132b | Placebo arm counts: 99, 109, 122 |

| 5 | 176 | 106b | 185 | Placebo arm counts: 288, 206, 340 |

| 6 | 196 | 106b | 61b | Completed study |

| 7 | 204 | 150 | 144b | Completed study |

| 8 | 244 | 229 | 141b | Placebo arm counts: 240, 274, 310 |

| 9 | 284 | 250 | 110b | Completed study |

Patients 10 through 33 had no episodes of thrombocytopenia during treatment with niacinamide. Three patients (in addition to patients 3 and 4) had thrombocytopenia during the placebo arm.

Platelet counts of <150.

Adverse Effects

Two patients complained of diarrhea while receiving niacinamide, one of whom had diarrhea before use of the study drug. This patient had spontaneous resolution of his symptoms without a reduction in dosage. The other had a dosage reduction from 750 to 500 mg twice daily with subsequent symptomatic improvement. No diarrhea was reported during placebo therapy. One patient complained of a rash on his abdomen during week 8 of niacinamide, which resolved after 4 d. There were no reports of flushing.

During the course of the study, eight patients were admitted to the hospital. Four were admitted during the placebo arm with diagnoses of osteoarthritis, septic arthritis, and volume overload (two patients). On niacinamide, three patients were admitted with diagnoses of volume overload, a nonhealing foot ulcer, and osteomyelitis. The last patient was excluded in the per-protocol analysis. One patient developed pneumonia during the washout period. There were no deaths.

Per-Protocol Analysis

A total of 25 of the 33 patients were ≥80% compliant with the study on the basis of pill counts and were assessed in the per-protocol analysis. The results parallel the findings described among the total study population (Table 5). Serum phosphorus rose insignificantly (from 5.59 to 5.96 mg/dl; P = 0.40) on placebo but decreased significantly from 6.45 to 5.28 mg/dl (P = 0.002) with niacinamide. There was a statistically significant difference between the mean change in serum phosphorus on placebo (+0.37 mg/dl; 95% CI −0.37 to 1.11 mg/dl) and the mean change on niacinamide (−1.17 mg/dl; 95% CI −0.52 to −1.82 mg/dl; P = 0.002; Figure 5). As expected, there was a concomitant fall in the calcium phosphorus product with niacinamide, from 61 to 51 mg2/dl2 (P = 0.003); serum calcium remained stable. Neither serum calcium nor calcium-phosphorus product changed significantly during placebo therapy. iPTH and uric acid levels remained the same in both arms. The compliant subset showed no change in total cholesterol, triglycerides, or LDL during either arm, but HDL levels after treatment with niacinamide approached significance (49 to 58 mg/dl; P = 0.07) while remaining unchanged in the placebo arm. During the 8-wk study period, the platelet count in the compliant subset fell from 214,000 to 197,000 (P = 0.10) during niacinamide. Among patients with thrombocytopenia described in Table 4, only patients 2 and 8 were <80% compliant with the study regimen.

Table 5.

Per-protocol analysis

| Parameter | Placebo Arm

|

Niacinamide Arm

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 9 | P | Week 1 | Week 9 | P | |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 5.59 ± 1.53 | 5.96 ± 1.54 | NS | 6.45 ± 1.33 | 5.28 ± 1.22 | 0.002 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.41 ± 0.58 | 9.60 ± 0.73 | NS | 9.47 ± 0.71 | 9.58 ± 0.64 | NS |

| Calcium-phosphorus product (mg2/dl2) | 52.47 ± 14.26 | 57.02 ± 14.88 | NS | 61.00 ± 12.88 | 50.54 ± 11.46 | 0.003 |

| iPTH (pg/ml) | 296 ± 182 | 277 ± 219 | NS | 305 ± 254 | 311 ± 194 | NS |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6.95 ± 1.77 | 6.67 ± 1.67 | NS | 7.01 ± 1.67 | 6.70 ± 1.56 | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 139 ± 29 | 134 ± 27 | NS | 137 ± 27 | 143 ± 26 | NS |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 56 ± 21 | 54 ± 28 | NS | 58 ± 27 | 55 ± 22 | NS |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 52 ± 17 | 50 ± 17 | NS | 49 ± 16 | 58 ± 20 | 0.070 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 153 ± 73 | 148 ± 80 | NS | 150 ± 73 | 157 ± 84 | NS |

| Platelet (1000/mm3) | 214 ± 72 | 224 ± 59 | NS | 214 ± 52 | 197 ± 56 | NS |

Figure 5.

Serum phosphorus is represented by the solid line during the placebo arm and the dotted line during niacinamide. Among compliant patients, a more pronounced difference was noted in the change in serum phosphorus between placebo and niacinamide (+0.37 on placebo versus −1.17 mg/dl on niacinamide; P = 0.002). Placebo n = 25; niacinamide n = 25.

Discussion

The two major forms of vitamin B3 are niacin (or nicotinic acid) and its amide, niacinamide, also known as nicotinamide. Because niacinamide serves as a central component of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, it plays an important role in sustaining several crucial metabolic processes. As such, supplementation may be useful over a broad range of metabolic disorders. In the clinical setting, niacinamide is used primarily for the treatment of acne and pellagra; however, niacinamide has also been studied in insulin-dependent diabetes, where it may preserve pancreatic β cells (12), and ischemia-reperfusion injury, where it inhibits nitric oxide synthase (13). Niacinamide may mediate a variety of protective mechanisms through downregulation of TNF-α (14), increased free radical scavenging (15), and inhibition of poly-ADP-ribose synthetase, an emerging target for cardiovascular disease and cancer (16). Niacinamide is now known to inhibit sodium/phosphorous transport in both renal and intestinal brush borders, stimulating interest in its use for phosphorus reduction among patients with chronic kidney disease.

In large, multicenter studies, elevated serum phosphorus has been associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality in patients with ESRD (1,17,18). Hyperphosphatemia is linked to cardiovascular risk as well as bone disease (19,20), and the hyperphosphatemic milieu may promote vascular calcification through cellular changes in vascular smooth muscle cells (21). Previous open-label studies by Takahashi et al. (10) and Sampathkumar et al. (22) demonstrated that niacinamide lowers serum phosphorus levels in maintenance hemodialysis patients when traditional binding agents are withheld. This study is the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the effectiveness of niacinamide on phosphorus reduction in conjunction with phosphorus binders.

After 8 wk of therapy, patients in our study had a statistically and clinically significant drop in serum phosphorus and calcium-phosphorus product, whereas serum calcium and uric acid levels remained unchanged. The reduction in serum phosphorus and calcium-phosphorus product was more pronounced in the compliant subgroup analysis. The fall in phosphorus was most notable during the initial 2-wk period, which was associated with highest serum phosphorus levels and the lowest dosage (250 mg twice daily) of niacinamide; however, levels continued to decrease through the titration to 750 mg twice daily. Phosphorus levels may have continued to fall without titration to higher dosages, and further studies comparing different dosages for longer time periods are needed to address this issue.

The effect of niacinamide on HDL levels was somewhat surprising. Although niacin is known to increase serum HDL, previous reports suggested that in normal and hyperlipidemic individuals, niacinamide does not have similar effects on lipid metabolism (23,24). Although a detailed mechanism for their distinctive actions has yet to be understood, a nicotinic acid (niacin) receptor that binds niacin but not the nutritionally equivalent amide form, niacinamide, has been characterized (25,26). The effects of these compounds in uremic individuals is even less well studied; however, Takahashi et al. (10) reported that niacinamide raised HDL from 47 to 67 mg/dl (P < 0.0001) and lowered LDL from 79 to 70 mg/dl (P < 0.01) in Japanese patients on hemodialysis. Our study demonstrated an increase in HDL of 11 mg/dl (a 21.5% increase) with niacinamide, although no LDL-lowering effect was seen. The kinetics of the HDL changes could not be characterized because lipid panels were drawn only at the start and completion of the treatment arms. Of note, most patients in our study were concomitantly treated with sevelamer, which lowers LDL via bile acid binding (27,28). This may obscure further lipid lowering by niacinamide. The cumulative effect of niacinamide on lipid metabolism observed in our study may have important benefits in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients and warrants further investigation.

Niacinamide seems to be well tolerated in the general population (29). Even at our maximum daily dosage of 1500 mg, there were no major adverse effects. Only one patient (of 33) required a dosage adjustment because of diarrhea, which resolved when niacinamide was decreased from 1500 to 1000 mg/d. This is in marked contrast to a report by Delanaye et al. (5) that noted the occurrence of diarrhea in five of six patients enrolled in an open-label trial of the safety and efficacy of niacinamide. The symptoms from that report began at a mean niacinamide dosage of 1050 ± 447 mg and resolved after drug cessation. Patients in that study were on calcium-based and/or sevelamer-based binder regimens. The authors speculated that co-administration of phosphorus binders with niacinamide may have contributed to the severe diarrhea, because a much lower percentage of patients (7.8%) in Takahashi's cohort developed diarrhea when niacinamide was administered alone (10). In our study, 76% were on concurrent sevelamer hydrochloride, 12% were on lanthanum carbonate, and 45% were on calcium-based binders, and only 6% (two of 33) of the total study population and 8% (two of 25) of the compliant subset complained of diarrhea. No patients were removed from the study, and there were no deaths during the study period. Hospitalizations were roughly equivalent between the two groups, with all admissions related to underlying comorbidities and not the administration of niacinamide. Hospitalization may also transiently affect serum phosphorus levels and confound results; however, when hospitalized patients are removed from the per-protocol analysis, a significant change in phosphorus during niacinamide treatment is still noted (6.6 to 5.2 mg/dl; P < 0.05), whereas phosphorus remains unchanged during placebo.

Thrombocytopenia has been a concern from previous studies of niacinamide, and our analysis did find a trend toward decreasing platelet counts on niacinamide. Nevertheless, no clinical manifestations of thrombocytopenia complicated the administration of study drug in our study. The mechanism by which niacinamide may decrease platelet counts is not fully understood. Studies with nicotinic acid suggested that thrombocytopenia may be mediated through a decrease in thyroxin-binding globulin (4). Although clinical manifestations did not occur during our study period, further investigation is warranted to evaluate the effect of niacinamide on platelets for a longer period of administration. For now, monitoring for thrombocytopenia in dialysis patients on niacinamide is prudent.

This study supports the usefulness of niacinamide in hemodialysis patients with hyperphosphatemia. Furthermore, it seems to be well tolerated, and its effect on serum HDL levels is particularly appealing for a population at high risk for cardiovascular disease. As demonstrated here, niacinamide can be used in conjunction with phosphorus binders, although it does not need to be administered with meals. A recent study found that niaspan (prolonged-release niacin) also reduced phosphorus and raised HDL levels in dialysis patients after washout from calcium-based binders (30). Although both forms of vitamin B3 have now shown favorable effects on lipid and phosphorus levels, they are clinically distinguished by distinct differences in adverse effects. Flushing remains an important limitation to the titration of niacin in some patients, whereas further studies are needed to evaluate niacinamide's effect on platelet counts.

Conclusions

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial demonstrates that niacinamide is effective in controlling serum phosphorus when co-administered with phosphorus binders in patients on hemodialysis. Moreover, niacinamide increased serum HDL levels. The combination of phosphorus reduction with a beneficial change in lipid profiles makes niacinamide an attractive agent for further investigation and use for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

D.O.Y. received support for this study through the Amgen Fellowship Support Stipend during the 2006 to 2007 academic year.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Block GA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Levin NW, Port FK: Association of serum phosphorus and calcium-phosphorus product with mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients: A national study. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 607–617, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block GA, Port FK: Re-evaluation of risks associated with hyperphosphatemia and hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients: Recommendations for a change in management. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 1226–1237, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42[Suppl 3]: S1–S201. 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien T, Silverberg J, Nguyen T: Nicotinic acid-induced toxicity associated with cytopenia and decreased level of thyroxin-binding globulin. Mayo Clin Proc 67: 465–468, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delanaye P, Weekers L, Krzesinski J: Diarrhea induced by high doses of nicotinamide in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 69: 1914, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berndt TJ, Pfeifer J, Knox F, Kempson SA, Dousa TP: Nicotinamide restores phosphaturic effect of PTH and calcitonin in phosphate deprivation. Am J Physiol 242: F447–F452, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kempson SA, Colon-Otero G, Ou SY, Turner ST, Dousa TP: Possible role of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide as an intracellular regulator of renal transport of phosphate in the rat. J Clin Invest 67: 1347–1360, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eto N, Miyata Y, Ohno H, Yamashita T: Nicotinamide prevents the development of hyperphosphatemia by suppressing intestinal sodium-dependent phosphate transporter in rats with a denin-induced renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 1378–1384, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katai K, Tanaka H, Tatsumi S, Fukunaga Y, Genjida K, Morita K, Kuboyama N, Suzuki T, Akiba T, Miyamoto K, Takeda E: Nicotinamide inhibits sodium dependent phosphate cotransport activity in rat small intestine. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 1195–1201, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi Y, Tanaka A, Nakamura T, Fukuwatari T, Shibata K, Shimada N, Ebihara I, Koide H: Nicotinamide suppresses hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 65: 1099–1104, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Schulz K, Altman D, CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials): The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 134: 657–662, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenbarth G: Type 1 diabetes: A chronic autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med 314: 1360–1368, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su C, Liu D, Kao S, Chen H: Nicotinamide abrogates acute lung injury caused by ischaemia/reperfusion. Eur Respir J 30: 199–204, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuzawa M, Satoh J, Muto G, Muto Y, Nishimura S, Miyaguchi S, Qiang XL, Toyota T: Inhibitory effect of nicotinamide on in vitro and in vivo production of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Immunol Lett 59: 7–11, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen HU, Jørgensen KH, Egeberg J, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Nerup J: Nicotinamide prevents interleukin-1 effects on accumulated insulin release and nitric oxide production in rat islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 43: 770–777, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horvath E, Szabo C: Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase as a drug target for cardiovascular disease and cancer: An update. Drug New Prospect 20: 171–181, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Block G, Klassen P, Lazarus J, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM: Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2208–2218, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Regidor D, Kovesdy CP, Kilpatrick RD, Shinaberger CS, McAllister CJ, Budoff MJ, Salusky IB, Kopple JD: Survival predictability of time-varying indicators of bone disease in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 70: 771–780, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saleh FN, Schirmer H, Sundsfjord J, Jorde R: Parathyroid hormone and left ventricular hypertrophy. Eur Heart J 24: 2054–2060, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeBoer IH, Gorodetskaya I, Young B, Hsu CY, Chertow GM: The severity of secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic renal insufficiency is GFR-dependent, race-dependent, and associated with cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2762–2769, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalhoub V, Shatzen E, Henley C, Boedigheimer M, McNinch J, Manoukian R, Damore M, Fitzpatrick D, Haas K, Twomey B, Kiaei P, Ward S, Lacey DL, Martin D: Calcification inhibitors and Wnt signaling proteins are implicated in bovine artery smooth muscle cell calcification in the presence of phosphate and vitamin D sterols. Calcif Tissue Int 79: 431–442, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampathkumar K, Selvam M, Sooraj YS, Gowthaman S, Ajeshkumar RN: Extended release nicotinic acid: A novel oral agent for phosphate control. Int Urol Nephrol 38: 171–174, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altschul R, Hoffer A, Stephen J: Influence of nicotinic acid on serum cholesterol in man. Arch Biochem 54: 558–559, 1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson L: Nicotinic acid: The broad spectrum lipid drug. A 50th anniversary review. J Intern Med 258: 94–114, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenzen A, Stannck C, Lang H, Andrianov V, Kalvinsh I, Schwabe U: Characterization of a G protein-coupled receptor for nicotinic acid. Mol Pharmacol 59: 349–357, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wise A, Ford S, Fraser N, Barnes AA, Elshourbagy N, Eilert M, Ignar DM, Murdock PR, Steplewski K, Green A, Brown AJ, Dowell SJ, Szekeres PG, Hassall DG, Marshall FH, Wilson S, Pike NB: Molecular identification of high and low affinity receptors for nicotinic acid. J Biol Chem 278: 9869–9874, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada K, Fujimoto S, Tokura T, Fukudome K, Ochiai H, Komatsu H, Sato Y, Hara S, Eto T: Effects of sevelamer on dyslipidemia and chronic inflammation in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail 27: 361–365, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burke S, Dillon M, Hemken D, Rezabek MS, Balwit JM: Meta-analysis of the effect of sevelamer on phosphorus, calcium, PTH, and serum lipids in dialysis patients. Adv Ren Replace Ther 10: 133–145, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gale E, Bingley P, Emmett C, Collier T, European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) Group: European nicotinamide diabetes intervention trial (ENDIT): A randomized controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet 363: 925–931, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller D, Mehling H, Otto B, Bergmann-Lips R, Luft F, Jordan J, Kettritz R: Niacin lowers serum phosphorus and increases HDL cholesterol in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 1249–1254, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]