Abstract

Background and objectives: Calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a well-described entity in end-stage kidney disease and renal transplant patients; however, little systematic information is available on calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes. This systematic review was designed to characterize etiologies, clinical features, laboratory abnormalities, and prognosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A systematic review of literature for case reports and case series of nonuremic calciphylaxis was performed. Cases included met the operational definition of nonuremic calciphylaxis–histopathologic diagnosis of calciphylaxis in the absence of end-stage kidney disease, renal transplantation, or acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy.

Results: We found 36 cases (75% women, 63% Caucasian, aged 15 to 82 yr) of nonuremic calciphylaxis. Primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, alcoholic liver disease, and connective tissue disease were the most common reported causes. Preceding corticosteroid use was reported for 61% patients. Protein C and S deficiencies were seen in 11% of patients. Skin lesions were morphologically similar to calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Mortality rate was 52%, with sepsis being the leading cause of death.

Conclusion: Calciphylaxis should be considered while evaluating skin lesions in patients with predisposing conditions even in the absence of end-stage kidney disease and renal transplantation. Nonuremic calciphylaxis is reported most often in white women. Mineral abnormalities that are invoked as potential causes in calcific uremic arteriolopathy are often absent, suggesting that heterogeneous mechanisms may contribute to its pathogenesis. Nonuremic calciphylaxis is associated with high mortality, and there is no known effective treatment.

Calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA), is a rare but well-described entity in end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and in renal transplant patients. Prevalence of CUA has been reported as 4% in hemodialysis patients (1), and the incidence of this disorder may be increasing in patients with ESKD (2). The reasons for the increasing incidence of CUA are unclear. Although abnormal bone and mineral metabolism, hyperparathyroidism, and vitamin D therapy are often assumed to contribute to CUA, the mechanisms of disease are poorly understood; therefore, therapeutic strategies are of unproven benefit, and mortality remains high.

Calciphylaxis has also been reported in patients without ESKD; however, little systematic information is available on calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes. We performed a systematic review of calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes (NUC) to characterize the etiologies, clinical features, laboratory abnormalities, and prognosis of NUC. Detailed exploration of the clinical features of NUC could help inform further understanding of CUA.

Materials and Methods

Two authors (S.N. and J.H.) searched MEDLINE, Ovid, Embase, and Google Scholar independently and in duplicate, using the MeSH terms [Calciphylaxis and etiology or causes]. Cases included were those that met the operational definition of NUC–histopathologic diagnosis of calciphylaxis in the absence of ESKD, severe chronic kidney disease defined as serum creatinine >3 mg/dl or creatinine clearance <15 ml/min, acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy, and renal transplantation. There were no language restrictions. We reviewed references of all reports for additional cases. We used the related articles link and searched the citations of reports in the ISI Science Citation Index to identify additional reports. We independently reviewed the full text of these articles and abstracted data on age, gender, race, etiologic conditions, clinical features (duration of onset, location and morphology of lesions), laboratory parameters, offered treatments, and outcomes. Summary tables illustrating this information were prepared.

Results

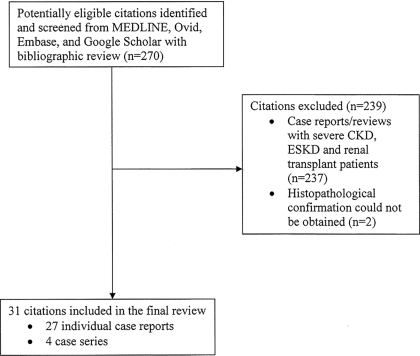

We identified 31 citations including 36 cases of NUC (3–33). These included 27 individual case reports (3,5,7–25,27–32) and four case series (4,6,26,33). A summary of the literature search strategy is provided in Figure 1. All of the included cases had histopathologic findings consistent with calciphylaxis. The most commonly reported histopathologic findings were calcifications of medium and/or small arteries (n = 31) along with ischemia (n = 15) and necrosis of subcutaneous fat (n = 10). Other findings that were reported included presence of microthrombi (n = 7), widespread septal panniculitis (n = 3), and endovascular fibrosis (n = 2). Patients ranged in age from 15 to 82 yr; 15 patients were older than 60 yr, 17 patients were between 30 and 50 yr, and three patients were younger than 30 yr. Most patients were women (n = 27), and for the 18 cases for which race was reported, 15 were white.

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search strategy. CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease.

Primary hyperparathyroidism (4,7,19,24,27,29,33), connective tissue diseases (6,20,28), alcoholic liver disease (9,11,13,14,16,22), and malignancies (5,15,17,21,23,30,31) were the most common causes of NUC (Table 1). Diabetes (26), chemotherapy-induced (cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, and fluorouracil) protein C and S deficiency (18), Crohn disease (3), POEMS syndrome (12), vitamin D deficiency (10), weight loss (25), chronic kidney disease (not ESKD) (32), and osteomalacia treated with nadroparin calcium (8) were the remaining reported etiologic conditions. In 22 cases, corticosteroid use was an associated predisposing factor (3,6,7,12,13,20,21,23,28,30,33), warfarin use was reported in nine cases (5,6,31), albumin or blood transfusions were reported in seven cases (4,9,12–15,19), and protein C or S deficiency was reported in four cases (9,16,18,20). Precipitating trauma leading to cutaneous lesions was reported in only two cases (10,21). Diabetes as an associated condition (not as a primary cause of NUC) was reported in eight cases (5,9,10,15,24,27,31).

Table 1.

Causes of nonuremic calciphylaxisa

| Cause | No. of Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary hyperparathyroidism | 10 (27.8) |

| Malignancyb | 8 (22.2) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 6 (16.7) |

| Connective tissue diseasesχ | 4 (11.1) |

| Diabetes | 2 (5.5) |

| Chemotherapy-induced protein C and S deficiency | 1 (2.8) |

| Crohn disease | 1 (2.8) |

| Osteomalacia treated with nadroparin calcium | 1 (2.8) |

| POEMS syndrome | 1 (2.8) |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 1 (2.8) |

| Weight loss | 1 (2.8) |

| CKD (not ESKD) | 1 (2.8) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease.

Cholangiocarcinoma, chronic myelocytic leukemia, malignant melanoma, metastatic breast cancer, and multiple myeloma; includes one case of metastatic parathyroid carcinoma causing primary hyperparathyroidism.

cGiant cell arteritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Most of the lesions of NUC were located on distal legs (n = 15), 10 cases had proximal lesions (thighs, abdomen, or buttocks), and 11 cases had both proximal and distal involvement. Involvement of upper extremities was reported in four cases (3,6,20,23), and genital involvement was reported in two cases (12,29); however, involvement of penis was not reported in NUC. Morphologically, the skin lesions appeared as indurated nodules, necrotic eschars, ulcerations, dry gangrene, and livedo reticularis and were similar in appearance to what has been described in CUA.

A summary of laboratory parameters in NUC cases is shown in Table 2. The majority of the cases had normal serum calcium (58%), normal serum phosphorous (69.4%), normal calcium phosphorous product (72.2%), and low or normal serum parathyroid hormone levels (50%). Marked elevation in serum calcium (equivalent to >12 mg/dl) was seen in six cases (17,19,21,22,34), and marked serum phosphorous elevations were seen in only two cases (3,15). Elevation of calcium-phosphorous product >50 was seen in only seven cases (3,7,17,19,21,22,33). Among patients who had primary hyperparathyroidism as a cause of NUC, serum parathyroid hormones were elevated to between 1.5 to 2.0 times the upper limit of normal range, unlike in patients with CUA, in whom serum parathyroid hormone levels are frequently elevated three to four times the upper limit of normal range. Renal function varied, but most patients had normal serum creatinine values (≤1.2 mg/dl). Only three patients had serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dl (3,15,19).

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters in nonuremic calciphylaxis

| Characteristic | No. of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | |

| normal (8.5 to 10.2) | 21 (58.0) |

| mild elevation (10.3 to 12.0) | 7 (19.4) |

| marked elevation (>12.0) | 6 (16.6) |

| not reported | 2 (5.6) |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | |

| low (<2.2) | 3 (8.3) |

| normal (2.2 to 4.5) | 25 (69.4) |

| mild elevation (4.6 to 6.0) | 3 (8.3) |

| marked elevation (>6) | 2 (5.6) |

| not reported | 3 (8.3) |

| Calcium-phosphorus product | |

| <50 | 26 (72.2) |

| >50 | 7 (19.4) |

| not reported | 3 (8.3) |

| Serum PTHa | |

| low | 4 (11.1) |

| normal | 14 (38.9) |

| high | 11 (30.5) |

| not reported | 7 (19.4) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | |

| ≤1.2 | 14 (42.4) |

| 1.3 to 1.5 | 2 (6.1) |

| 1.6 to 2.5 | 5 (13.9) |

| 2.6 to 3.0 | 3 (8.3) |

| not reported | 12 (33.3) |

Assay types and normal ranges of parathyroid hormone (PTH) assays varied in the included reports. We divided them as low, normal, and high on the basis of the interpretation of the values by the individual study authors.

For patients with NUC, the mortality rate was 52%, and sepsis was the most common cause of death, contributing to 50% of all deaths. Most of the deaths occurred between 2 wk and 1 yr after the diagnosis of NUC. Reported treatments included supportive wound care with pain control, empiric antibiotic therapy, treating underlying etiologic conditions (e.g., parathyroidectomy for patients with hyperparathyroidism), and removing potential precipitating factors (e.g., corticosteroids, albumin infusions). Vitamin D supplementation as treatment was given in three cases (6,24), and inorganic intravenous phosphorous was administered in one case (17). Systemic corticosteroids were used in the treatment of NUC in five cases (6,13,21,33); four of these five cases were met with mortality. None of the NUC cases reported modalities such as sodium thiosulfate, cinacalcet, or hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which have been reported for the treatment of CUA (34–36). Complete resolution of skin lesions was reported in 16 cases between 3 mo and 1 yr after diagnosis.

Discussion

Calciphylaxis was first described by Selye et al. (37) in 1961 as a systemic hypersensitivity reaction. In animal experiments, they induced calcification of various organs after animals had been exposed to one of several sensitizing agents referred to as “calcifiers” (e.g., dihydrotachysterol, vitamin D2, vitamin D3, parathyroid hormone), followed by exposure to a “challenger” (e.g., metallic salts such as iron and aluminum, egg albumin, trauma). A few years after Selye et al. coined the term, calciphylaxis was reported in humans as a syndrome primarily seen in uremic patients characterized histopathologically by small-vessel mural calcification, extravascular calcification, and thrombosis leading to ischemia with skin and soft tissue necrosis and high mortality.

In this systematic review of NUC, which is the largest to date, we were able to study 35 reported cases of NUC, eight of which were reported before 1990, eight between 1990 and 2000, 12 between 2001 and 2005, and eight in the past 2 yr. Although Selye et al. introduced the term “calciphylaxis” in 1961, the first cases that fit our operational definition of NUC were reported in 1956 by Bogdonoff et al. (4) and are included in this review. Reporting of NUC has clearly increased over time, suggesting rising incidence of NUC; alternatively, increased awareness that the condition can occur outside of ESKD and renal transplant recipients may have led to a greater number of cases being diagnosed and ultimately reported in the literature. Thus, although some have suggested that the increased incidence of CUA reflects more aggressive treatment of mineral metabolism and secondary hyperparathyroidism among dialysis patients, in fact, the apparent increase in CUA parallels that of NUC and may also be due to increased awareness and earlier skin biopsy.

It is speculated that metabolic abnormalities and therapies that are associated with uremia, such as secondary hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, vitamin D supplementation, and calcium-based phosphate binders, are precipitating factors in CUA (38). The histopathologic picture of prominent soft tissue calcification seemed to support that view. Thus, it is interesting to note that the majority of patients in this report had normal or low values of calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone, and one was vitamin D deficient. Although “consumption” of calcium and phosphorous during the precipitation process may partly explain normal or low serum levels of these minerals, and abnormalities of bone and mineral metabolism with associated therapies may be contributory to calciphylaxis in certain cases, the pathogenesis is likely far more complex than our current understanding and may represent a common histopathologic pattern of tissue injury in response to a variety of heterogeneous insults.

Deficiencies in vascular calcification inhibitors such as fetuin-A and matrix Gla protein (39–41) have now been postulated to play a key role in CUA, further expanding our understanding of the complexity of vascular calcification. Derangements of receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK), RANK ligand, and osteoprotegerin may also be involved in the pathogenesis of CUA because this system is involved in regulation of extraskeletal mineralization (42). Some of the factors that predispose to NUC (parathyroid hormone, corticosteroids, and liver disease) are known to increase the expression of RANK ligand and decrease the expression of osteoprotegerin, thus activating NF-κB or degrading the inhibitory protein of NF-κB (or a combination of these) (43–45). Warfarin may inhibit vitamin K–dependent carboxylation of matrix-Gla protein, decreasing the activity of the protein to inhibit calcification locally (46). In a case of weight loss–related calciphylaxis, increased levels of systemic matrix metalloproteinases were thought to be etiologically important (24); however, the pathogenesis of NUC is not well understood, and specific factors that induce this disorder in an individual patient are not known. Although the data are sparse, it is noteworthy that use of systemic corticosteroids to treat NUC was associated with high mortality in our study and in a previous case series.

A systematic review of this entity is limited by incomplete information, the lack of a standardized method of reporting, and possible selection and publication biases. Furthermore, although the recognition of NUC may be increasing in recent years, the lack of awareness about this condition may have resulted in underrecognition and then underreporting of this condition, limiting representativity of our systematic review. The reported etiologic conditions and predisposing factors listed in our review are as per the individual reports that were included in our review. Although we carefully analyzed each individual report included in our review to eliminate other possible causes of NUC, it is possible that some of the reported conditions are simply “associations” with the NUC and not necessarily a “cause” for this condition. Our review was limited to those cases with histopathologic confirmation, omitting cases of possible or probable NUC as suggested by imaging studies or bone scans, and those for which histopathologic confirmation could not be obtained (47,48). Although our method may have excluded some cases of true NUC, far more cases of NUC likely never reached clinical detection, a limitation that continues to challenge efforts to quantify accurately the syndrome's incidence and systematically analyze its risk factors.

Conclusions

NUC is a well-reported, often lethal entity that may be becoming more common. Most cases are due to primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancies, and connective tissue diseases. A high index of suspicion for NUC should be maintained while evaluating skin lesions in patients with these underlying conditions even in the absence of ESKD and renal transplantation. NUC is mostly seen in white women, and characteristic laboratory abnormalities that are seen in CUA may not be present in NUC. The pathogenesis of NUC remains unclear, and no effective specific treatments are available.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented as an abstract at the Spring Clinical Meeting of the National Kidney Foundation; April 3, 2008; Grapevine, TX.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Angelis M, Wong LL, Myers SA, Wong LM: Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: A prevalence study. Surgery 122: 1083–1089, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine A, Zacharias J: Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: Risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 61: 2210–2217, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barri YM, Graves GS, Knochel JP: Calciphylaxis in a patient with Crohn's disease in the absence of end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 773–776, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdonoff MD, Engel FL, White JE, Woods AH: Hyperparathyroidism. Am J Med 21: 583–595, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosler DS, Amin MB, Gulli F, Malhotra RK: Unusual case of calciphylaxis associated with metastatic breast carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol 29: 400–403, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouns K, Verbeken E, Degreef H, Bobbaers H, Blockmans D: Fatal calciphylaxis in two patients with giant cell arteritis. Clin Rheumatol 26: 836–840, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buxtorf K, Cerottini JP, Panizzon RG: Lower limb skin ulcerations, intravascular calcifications and sensorimotor polyneuropathy: Calciphylaxis as part of a hyperparathyroidism? Dermatology 198: 423–425, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campanelli A, Kaya G, Masouyé I, Borradori L: Calcifying panniculitis following subcutaneous injections of nadroparin-calcium in a patient with osteomalacia. Br J Dermatol 153: 657–660, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavel SM, Taraszka KS, Schaffer JV, Lazova R, Schechner JS: Calciphylaxis associated with acute, reversible renal failure in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 50: S125–S128, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couto FM, Chen H, Blank RD, Drezner MK: Calciphylaxis in the absence of end-stage renal disease. Endocr Pract 12: 406–410, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl PR, Winkelmann RK, Connolly SM: The vascular calcification-cutaneous necrosis syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 33: 53–58, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Roma I, Filotico R, Cea M, Procaccio P, Perosa F: Calciphylaxis in a patient with POEMS syndrome without renal failure and/or hyperparathyroidism: A case report. Ann Ital Med Int 19: 283–287, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fader DJ, Kang S: Calciphylaxis without renal failure. Arch Dermatol 132: 837–838, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreres JR, Marcoval J, Bordas X, Moreno A, Muniesa C, Prat C, Peyrí J: Calciphylaxis associated with alcoholic cirrhosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 20: 599–601, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goff HW, Grimwood RE: A case of calciphylaxis and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Cutis 75: 325–328, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goli AK, Goli SA, Shah LS, Byrd RP Jr, Roy TM: Calciphylaxis: A rare association with alcoholic cirrhosis. Are deficiencies in protein C and S the cause? South Med J 98: 736–739, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golitz LE, Field JP: Metastatic calcification with skin necrosis. Arch Dermatol 106: 398–402, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyal S, Huhn KM, Provost TT: Calciphylaxis in a patient without renal failure or elevated parathyroid hormone: possible aetiological role of chemotherapy. Br J Dermatol 143: 1087–1090, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khafif RA, Delima C, Silverberg A, Frankel R, Groopman J: Acute hyperparathyroidism with systemic calcinosis. Report of a case. Arch Intern Med 149: 681–684, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korkmaz C, Dündar E, Zubaroğlu I: Calciphylaxis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis without renal failure and hyperparathyroidism: The possible role of long-term steroid use and protein S deficiency. Clin Rheumatol 21: 66–69, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutlu NO, Aydin NE, Aslan M, Bulut T, Ozgen U: Malignant melanoma of the soft parts showing calciphylaxis. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 20: 141–146, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim SP, Batta K, Tan BB: Calciphylaxis in a patient with alcoholic liver disease in the absence of renal failure. Clin Exp Dermatol 28: 34–36, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mastruserio DN, Nguyen EQ, Nielsen T, Hessel A, Pellegrini AE: Calciphylaxis associated with metastatic breast carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 41: 295–298, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirza I, Chaubay D, Gunderia H, Shih W, El-Fanek H: An unusual presentation of calciphylaxis due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Pathol Lab Med 125: 1351–1353, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munavalli G, Reisenauer A, Moses M, Kilroy S, Arbiser JL: Weight loss-induced calciphylaxis: Potential role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Dermatol 30: 915–919, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mwipatayi BP, Cooke C, Sinniah RH, Abbas M, Angel D, Sieunarine K: Calciphylaxis: Emerging concept in vascular patients. Eur J Dermatol 17: 73–78, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nigwekar SU: An unusual case of nonhealing leg ulcer in a diabetic patient. South Med J 100: 851–852, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozbalkan Z, Calguneri M, Onat AM, Ozturk MA: Development of calciphylaxis after long-term steroid and methotrexate use in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med 11: 1178–1181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock B, Cunliffe WJ, Merchant WJ: Calciphylaxis in the absence of renal failure. Clin Exp Dermatol 25: 389–392, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raper RF, Ibels LS: Osteosclerotic myeloma complicated by diffuse arteritis, vascular calcification and extensive cutaneous necrosis. Nephron 39: 389–392, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riegert-Johnson DL, Kaur JS, Pfeifer EA: Calciphylaxis associated with cholangiocarcinoma treated with low-molecular-weight heparin and vitamin K. Mayo Clin Proc 76: 749–752, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smiley CM, Hanlon SU, Michel DM: Calciphylaxis in moderate renal insufficiency: Changing disease concepts. Am J Nephrol 20: 324–328, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkelmann RK, Keating FR Jr: Cutaneous vascular calcification, gangrene and hyperparathyroidism. Br J Dermatol 83: 263–268, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meissner M, Kaufmann R, Gille J: Sodium thiosulphate: A new way of treatment for calciphylaxis? Dermatology 214: 278–282, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson MR, Augustine JJ, Korman NJ: Cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol 143: 152–154, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podymow T, Wherrett C, Burns KD: Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 2176–2180, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selye H, Gentile G, Pioreschi P: Cutaneous molt induced by calciphylaxis in the rat. Science 134: 1876–1877, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Budisavljevic MN, Cheek D, Ploth DW: Calciphylaxis in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 978–982, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schafer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, Westenfeld R, Ketteler M, Floege J, Muller-Esterl W, Schinke T, Jahnen-Dechent W: The serum protein alpha 2-Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest 112: 357–366, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heiss A, DuChesne A, Denecke B, Grötzinger J, Yamamoto K, Renné T, Jahnen-Dechent W: Structural basis of calcification inhibition by alpha 2-HS glycoprotein/fetuin-A: Formation of colloidal calciprotein particles. J Biol Chem 278: 13333–13341, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyer E, Behringer RR, Karsenty G: Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature 386: 78–81, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bardin T: Musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Rheumatol 15: 48–54, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma YL, Cain RL, Halladay DL, Yang X, Zeng Q, Miles RR, Chandrasekhar S, Martin TJ, Onyia JE: Catabolic effects of continuous human PTH (1e38) in vivo is associated with sustained stimulation of RANKL and inhibition of osteoprotegerin and gene-associated bone formation. Endocrinology 142: 4047–4054, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang L, Xu J, Kumta SM, Zheng MH: Gene expression of glucocorticoid receptor a and b in giant cell tumour of bone: Evidence of glucocorticoid-stimulated osteoclastogenesis by stromal-like tumour cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 181: 199–206, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khoruts A, Stahnke L, McClain CJ, Logan G, Allen JI: Circulating tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 concentrations in chronic alcoholic patients. Hepatology 13: 267–276, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallin R, Cain D, Sane DC: Matrix Gla protein synthesis and gamma-carboxylation in the aortic vessel wall and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells: A cell system which resembles the system in bone cells. Thromb Haemost 82: 1764–1767, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almirall J, Pobo A, Luelmo J, Berna L: Post-infectious acute renal failure due to calciphylaxis: When processes go the wrong way round. J Nephrol 17: 575–579, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR: Calciphylaxis: Natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol 56: 569–579, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]